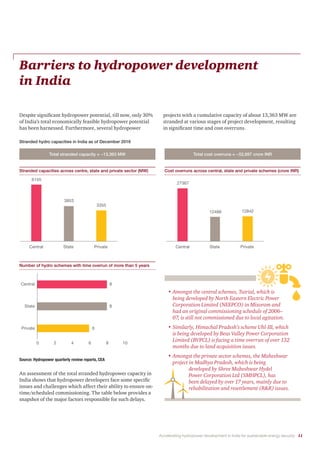

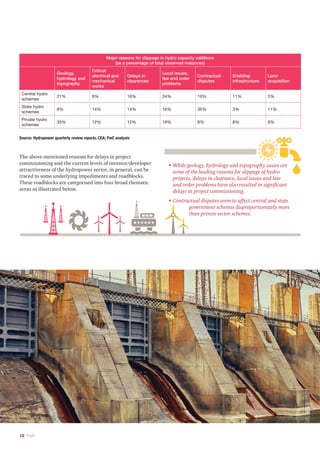

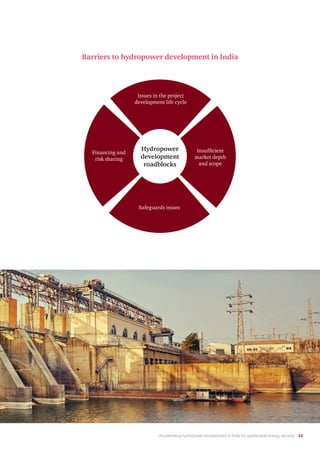

The document discusses accelerating hydropower development in India. It notes that while India has large hydropower potential, only a small portion has been developed so far. Recent renewable energy targets and expected electricity demand increases necessitate greater reliance on hydropower due to its ability to support the grid and balance the variability of renewables like solar and wind. However, hydropower development in India faces barriers like land acquisition challenges, environmental clearances, and lack of long-term power purchase agreements that increase costs. The document proposes an action plan to address these issues and create a level playing field for hydropower to attract more private sector investment and accelerate its development.