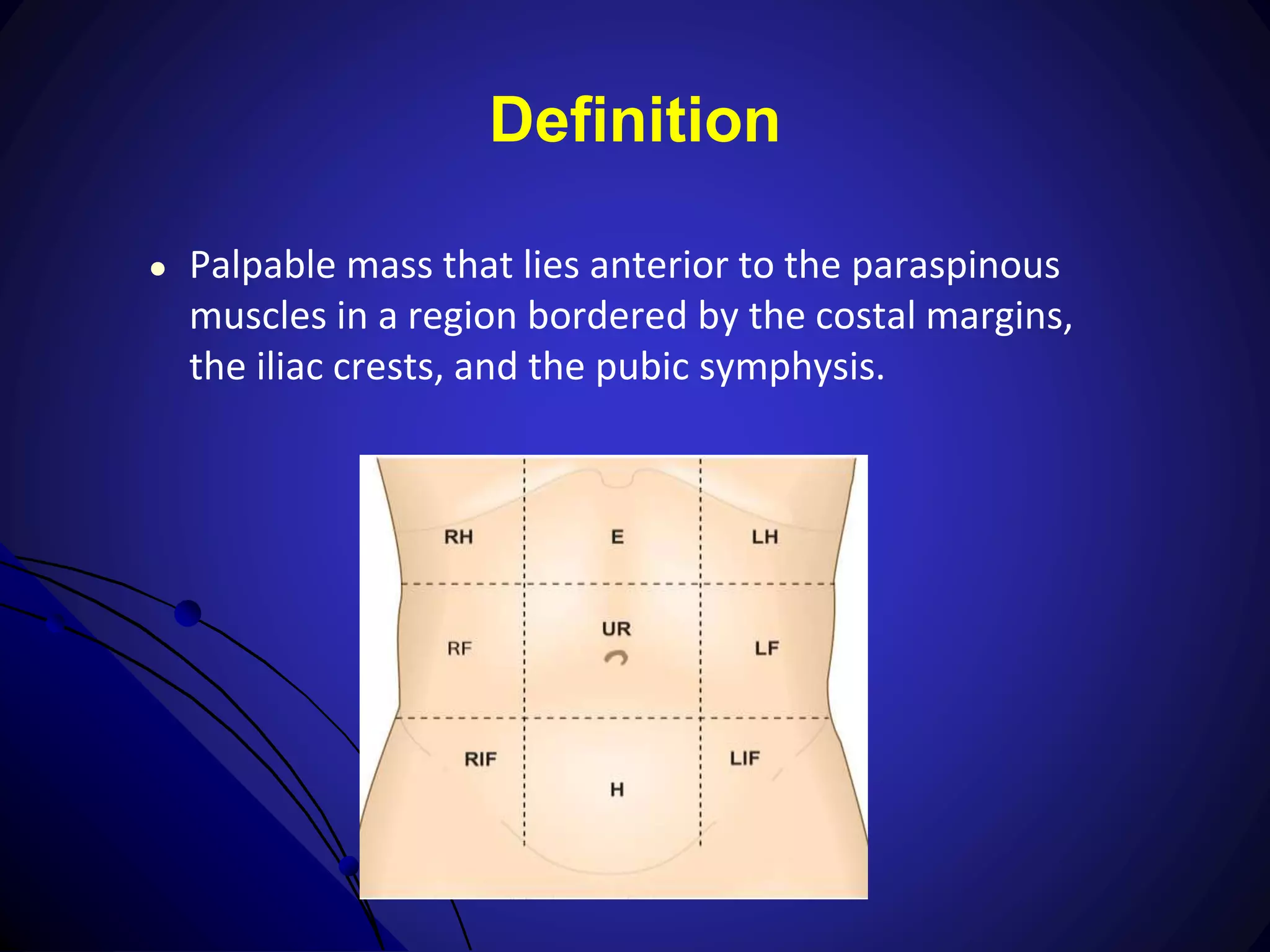

1) Physical examination and diagnostic testing are important for evaluating abdominal masses to determine the diagnosis and appropriate management. The exam involves inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation to determine the location, size, shape, consistency and other characteristics of the mass.

2) A thorough history is also required to understand associated symptoms, medical history, and develop a differential diagnosis. Laboratory tests and various imaging modalities like ultrasound, CT, and MRI can help identify the organ of origin and pathology.

3) In some cases where the diagnosis remains unclear after initial evaluation, further procedures like biopsy or exploratory surgery may be needed to establish the diagnosis and guide treatment planning. The goal is to tailor the