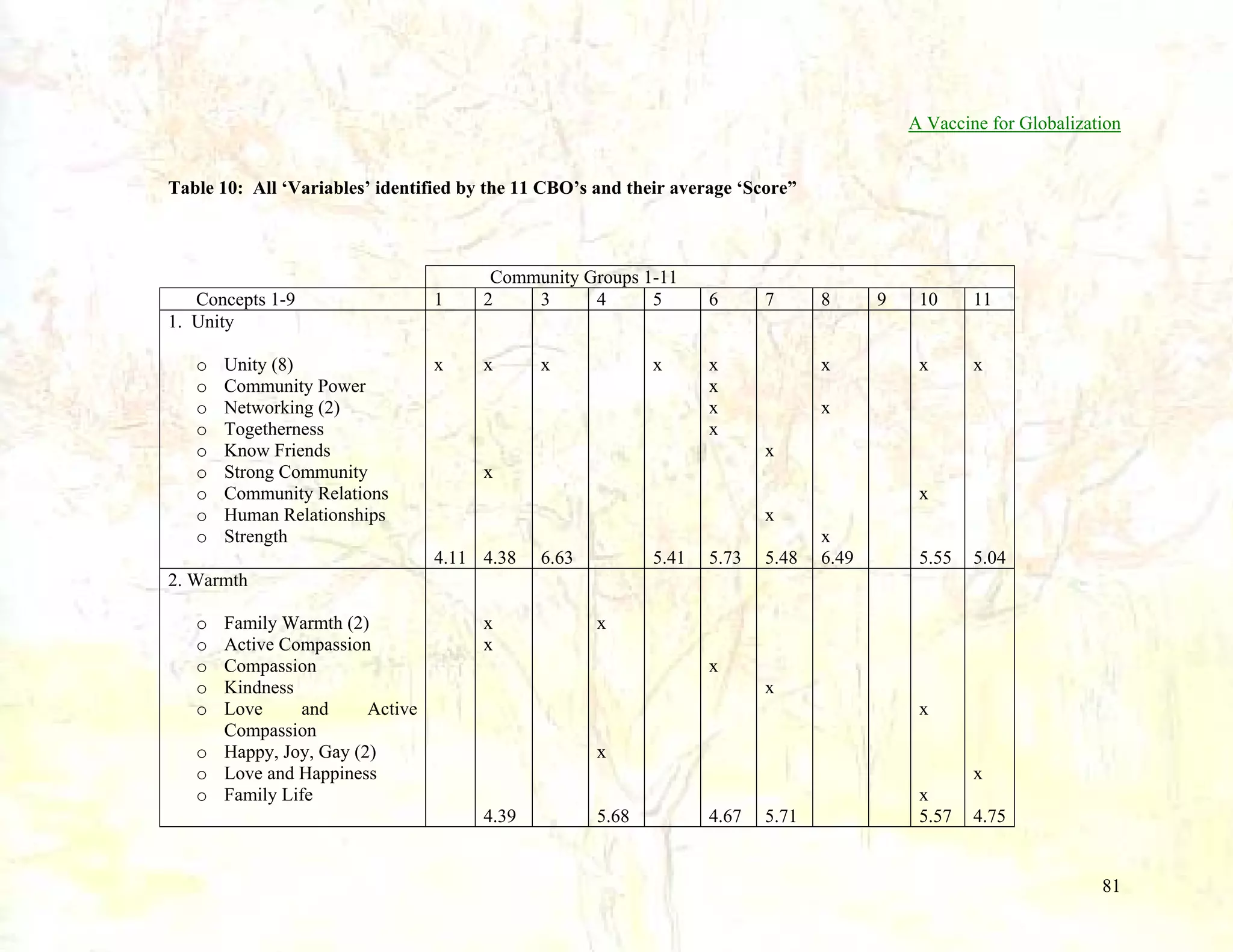

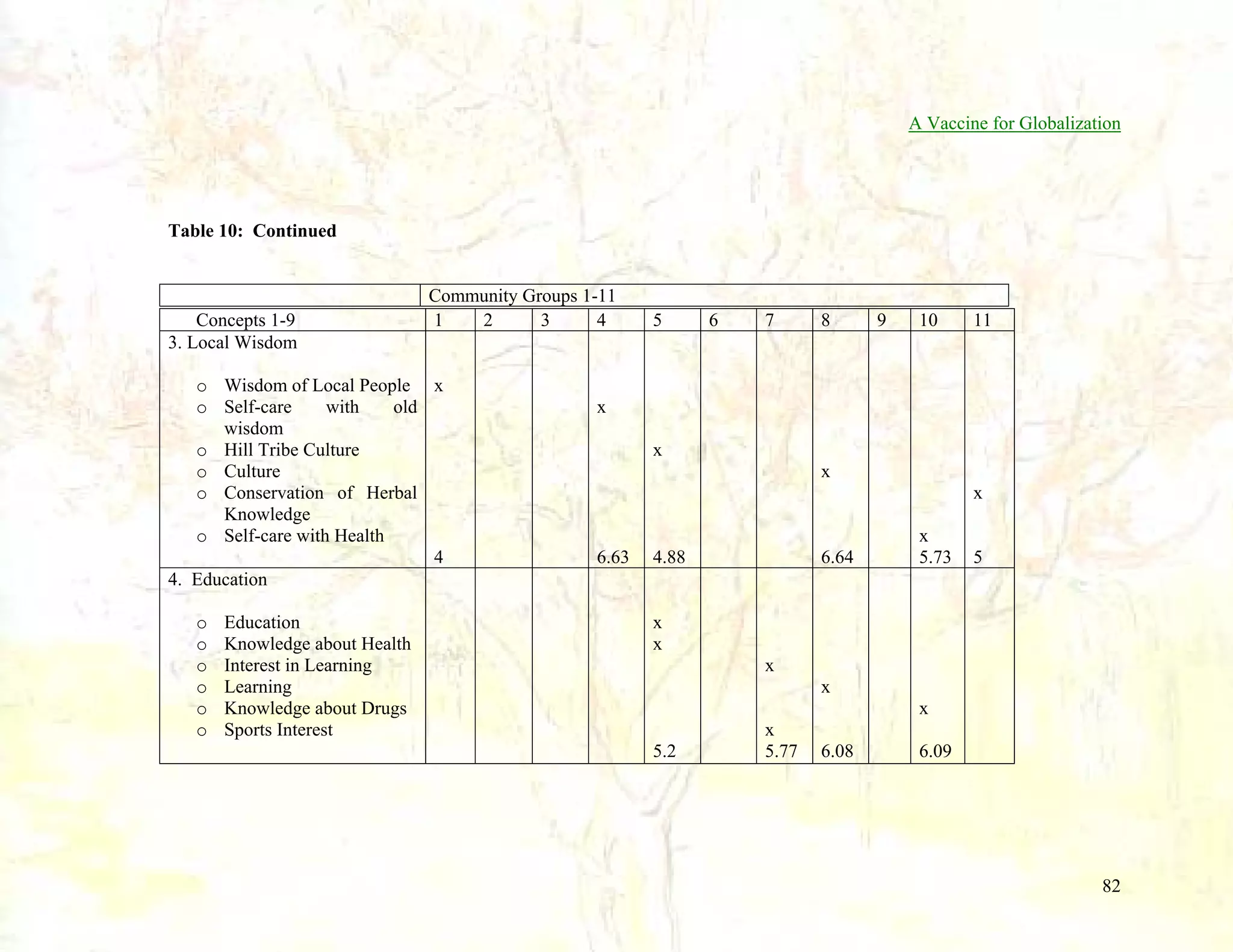

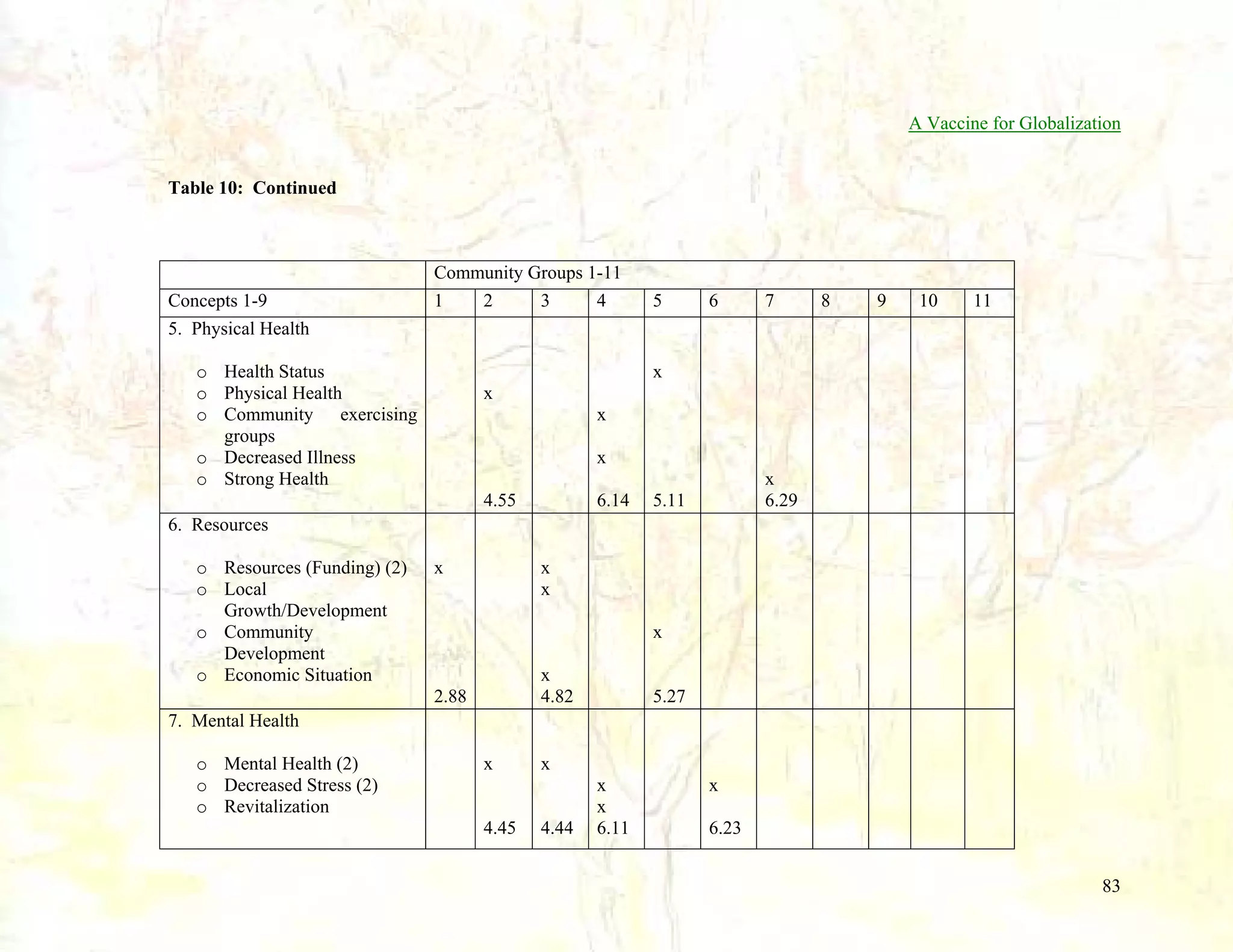

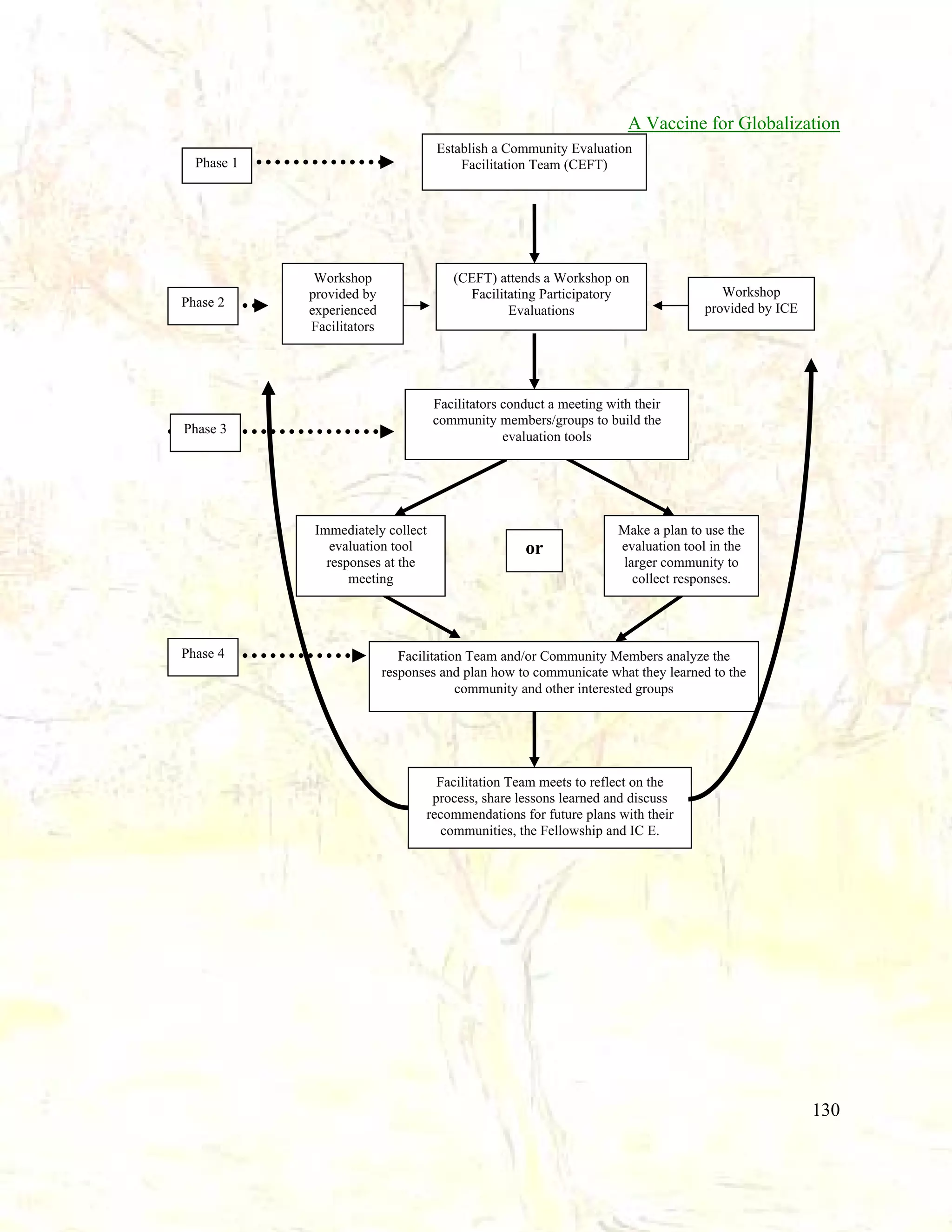

The document is a report produced by the Institute for Community Empowerment in Thailand and the Chiang Mai Health Promotion Network documenting their experiences with participatory action research and asset-based community development approaches. It describes how they worked with 11 community-based organizations to build capacity and empower community members to engage in decentralized healthcare. It also details how the communities developed a method to identify and evaluate social changes resulting from these asset-based approaches by asking how the projects have impacted community empowerment and self-determination. The report findings indicate that the asset-based work expanded beyond strengths and resources to also incorporate important cultural traditions like music, dance, and healing methods as a shared way of thinking.

![A Vaccine for Globalization

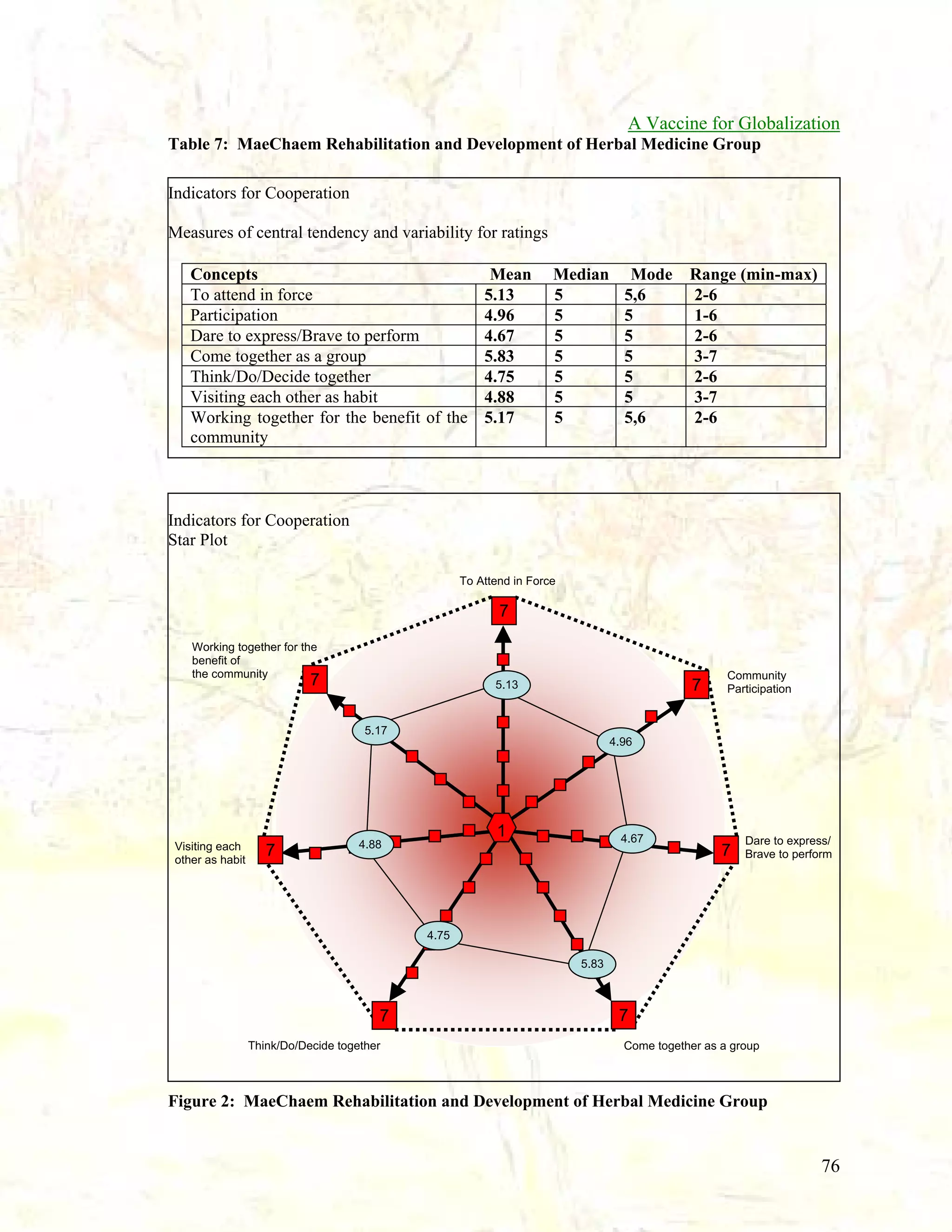

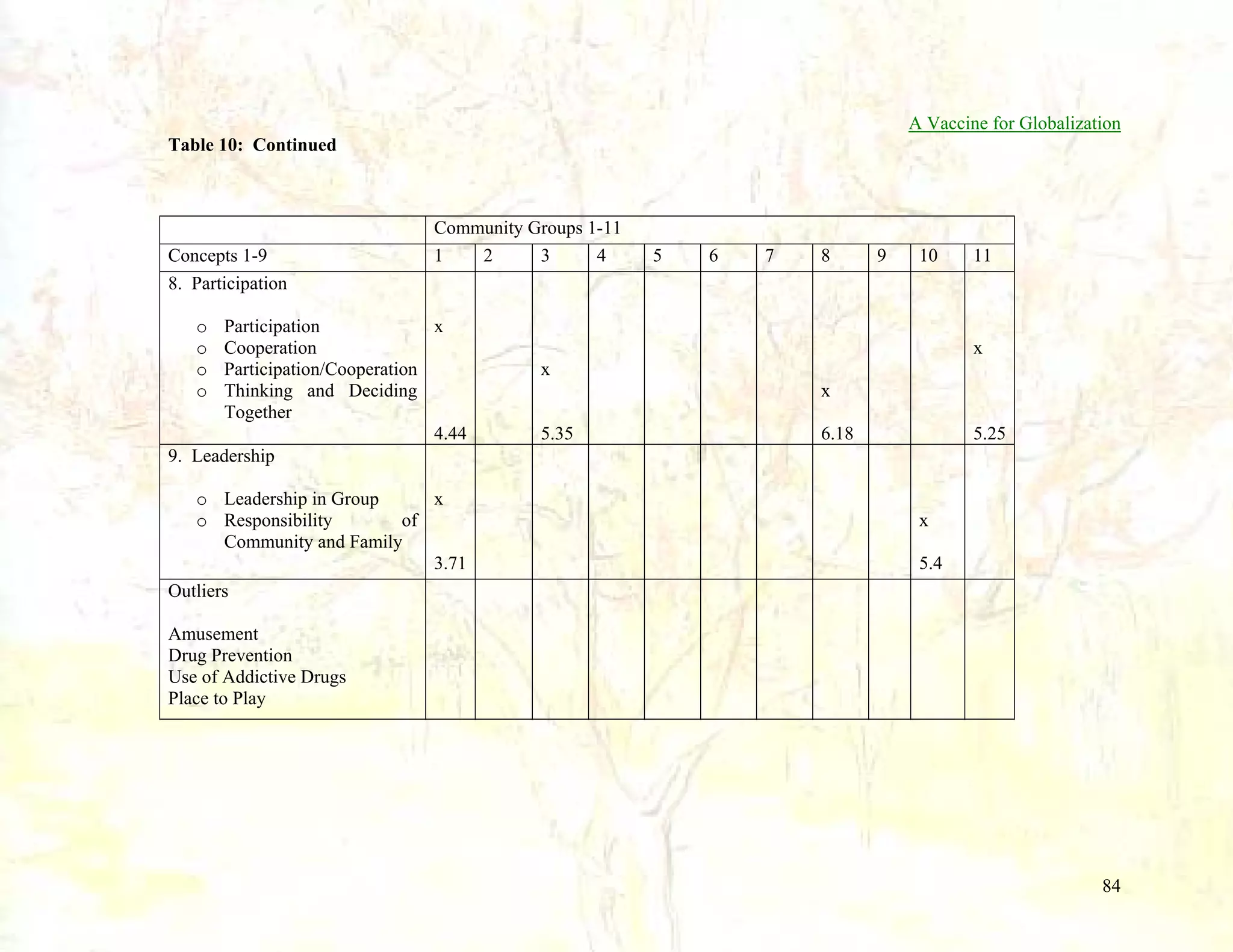

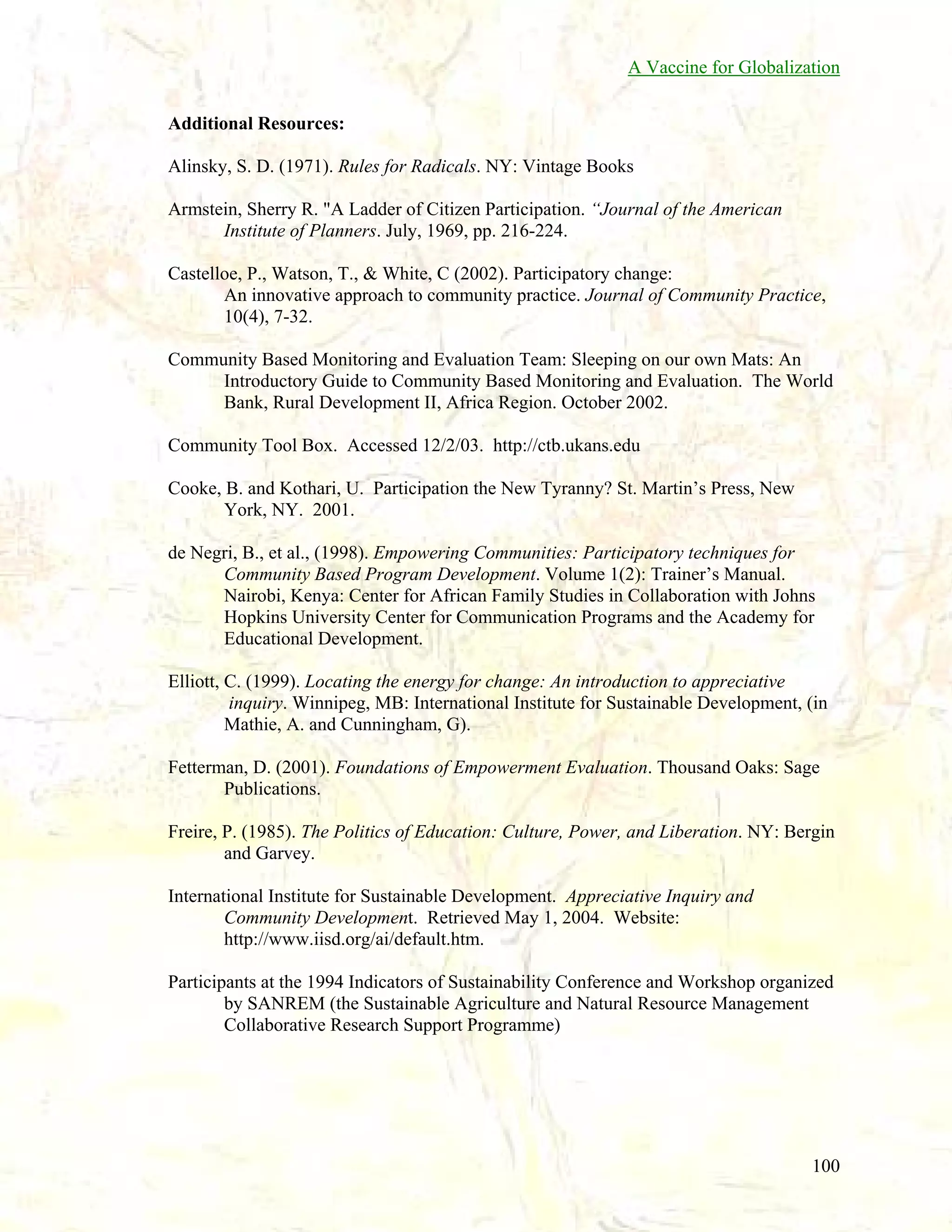

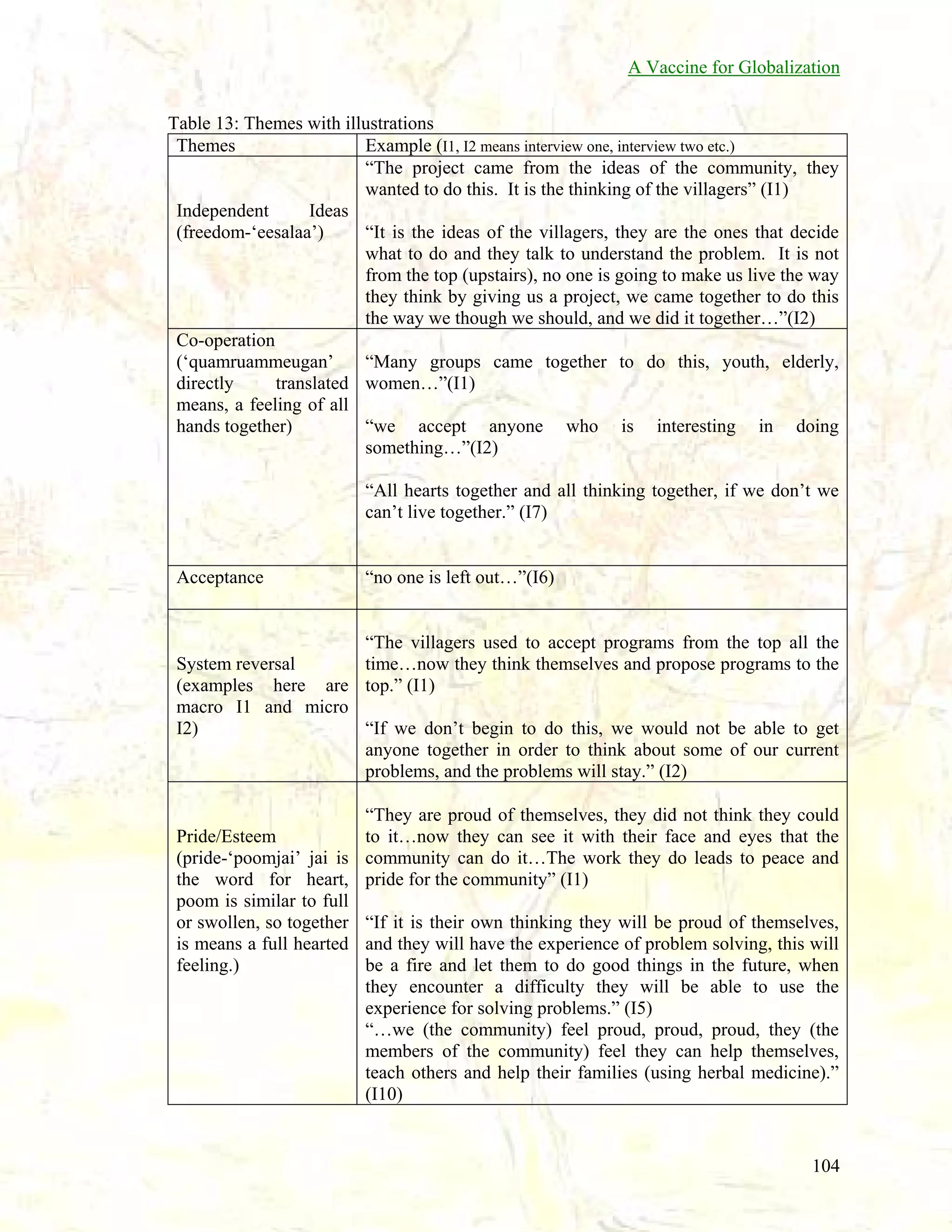

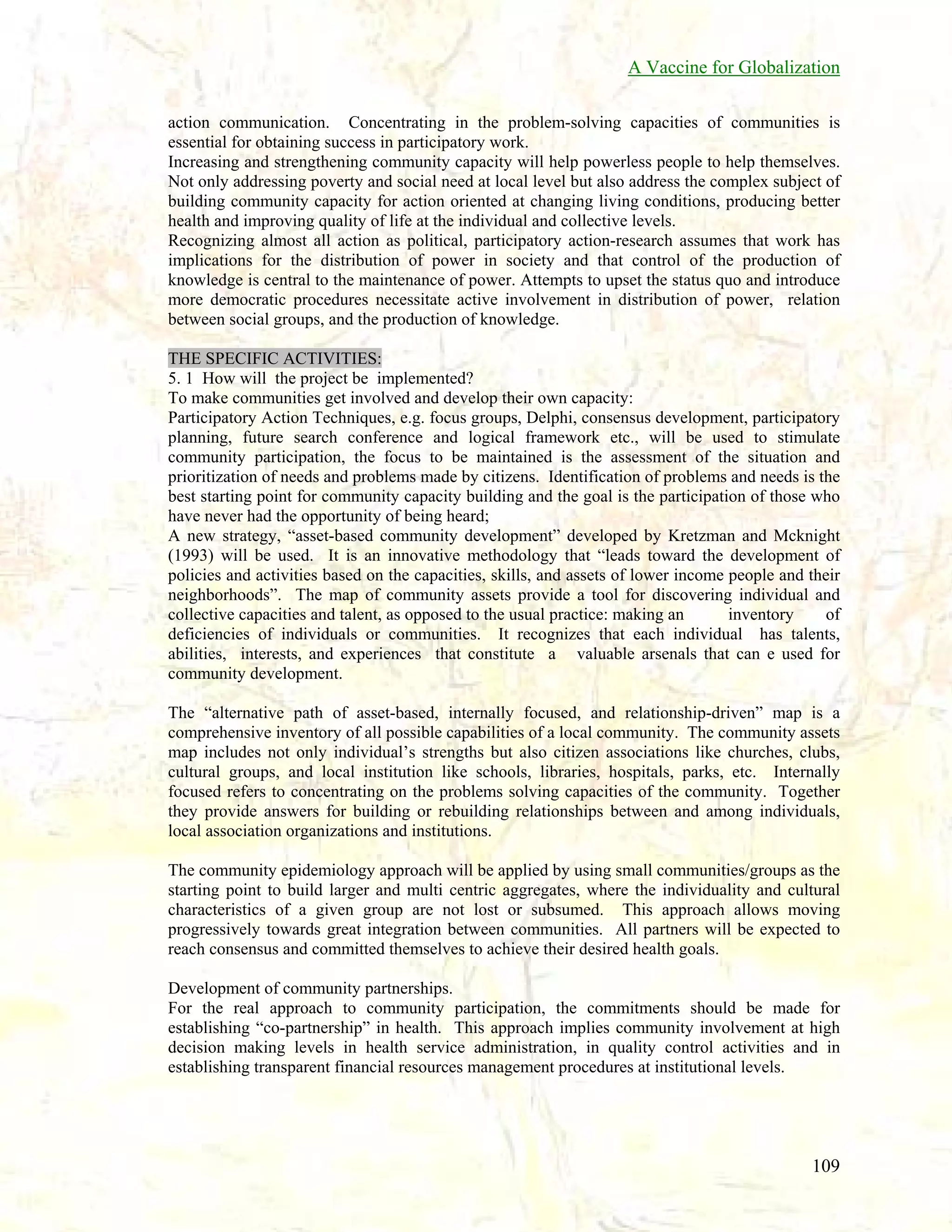

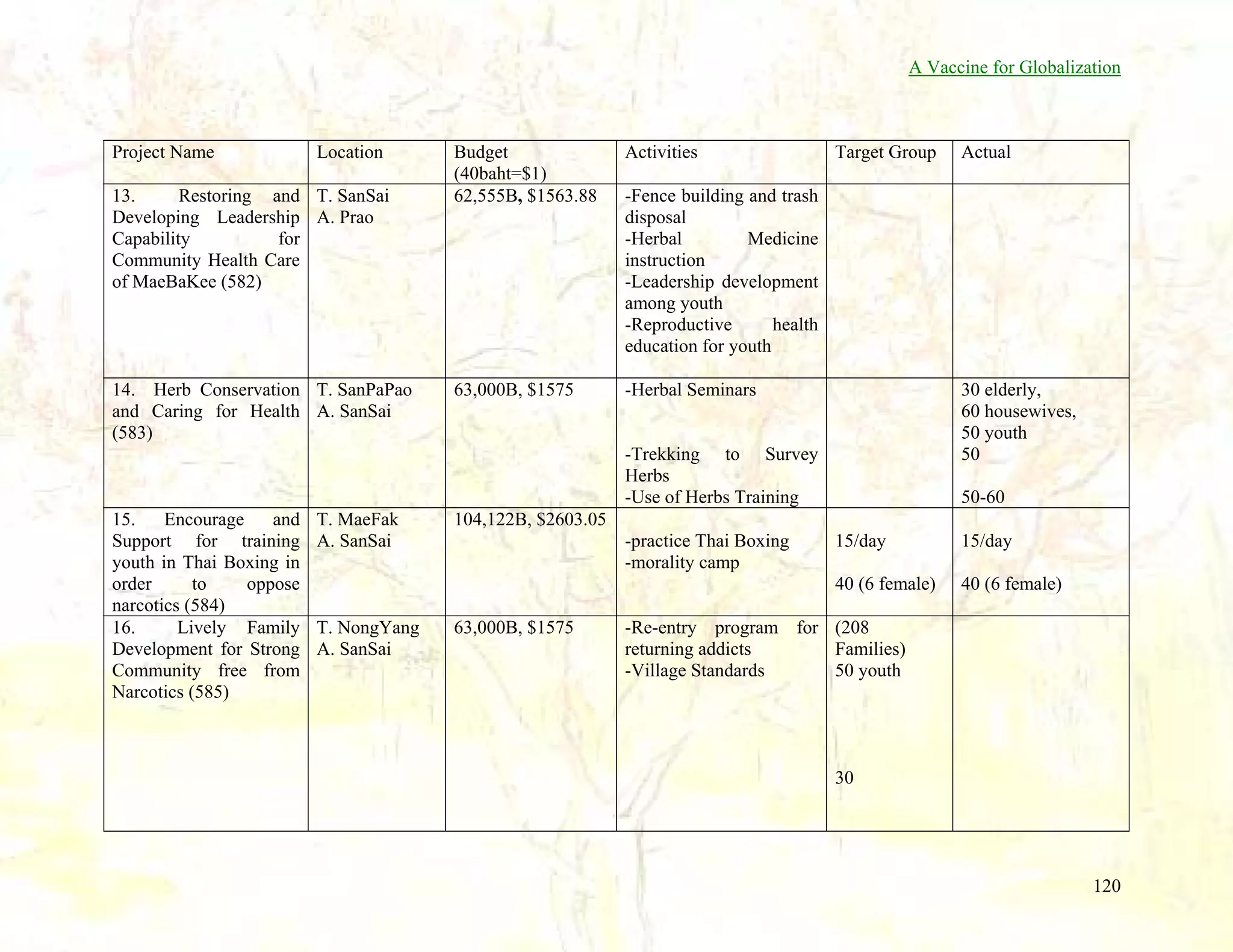

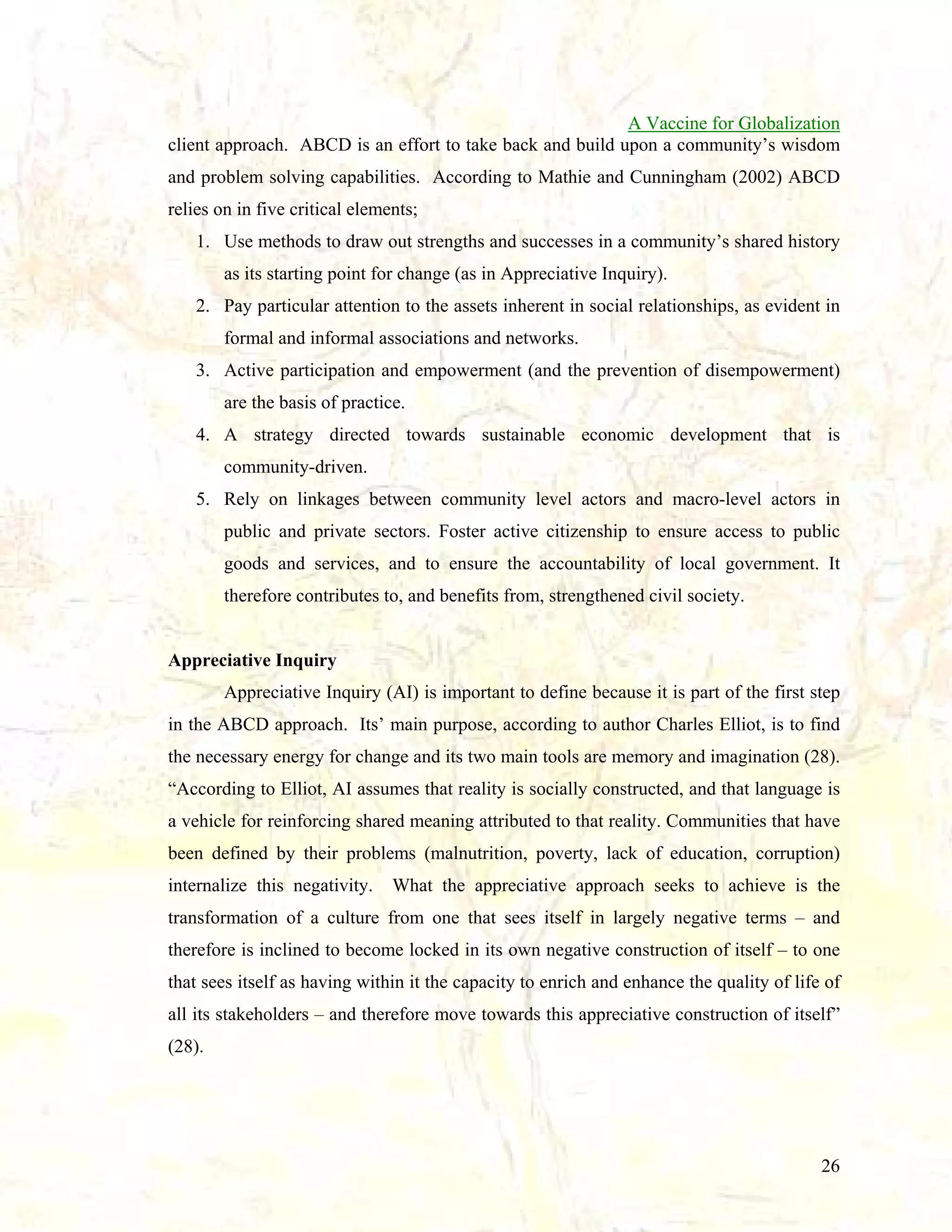

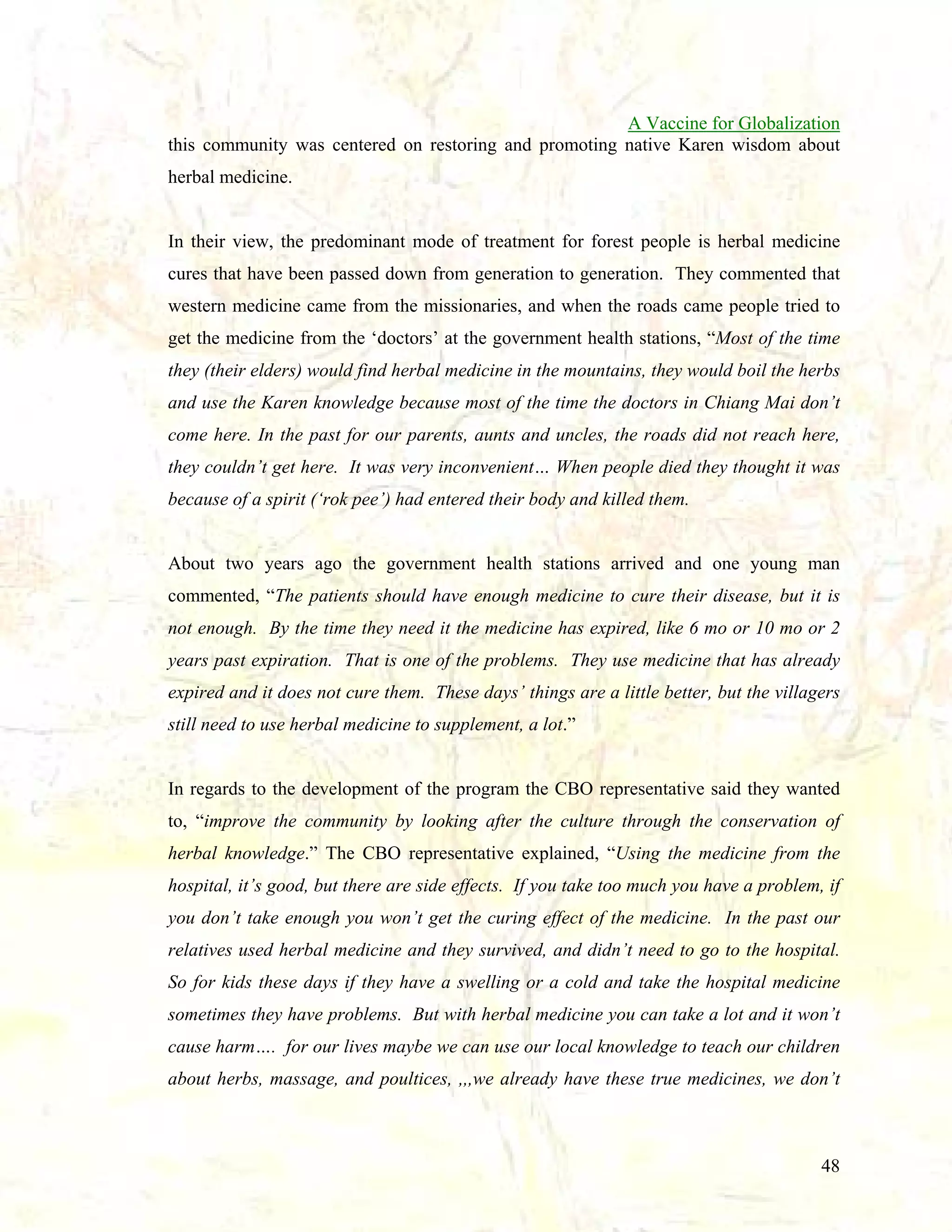

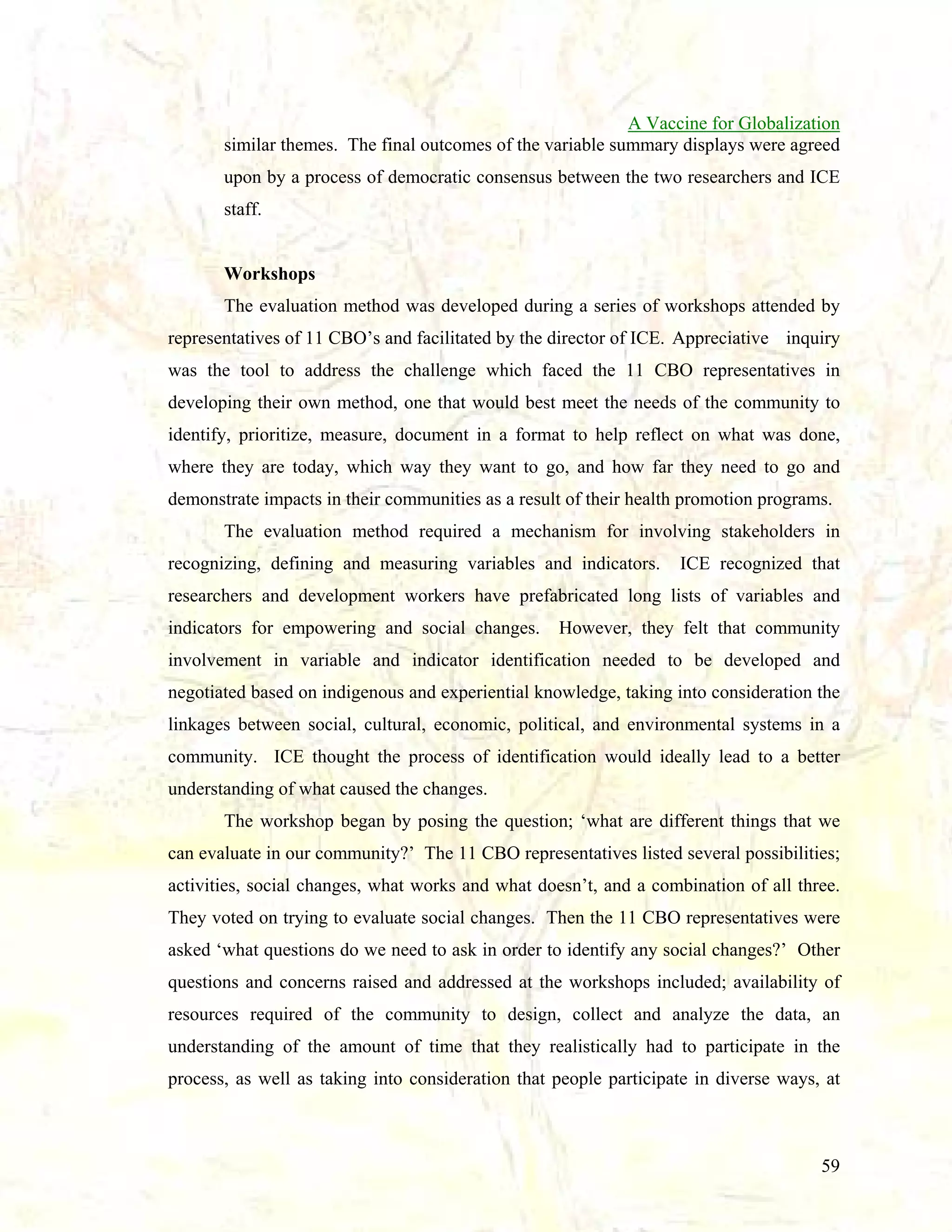

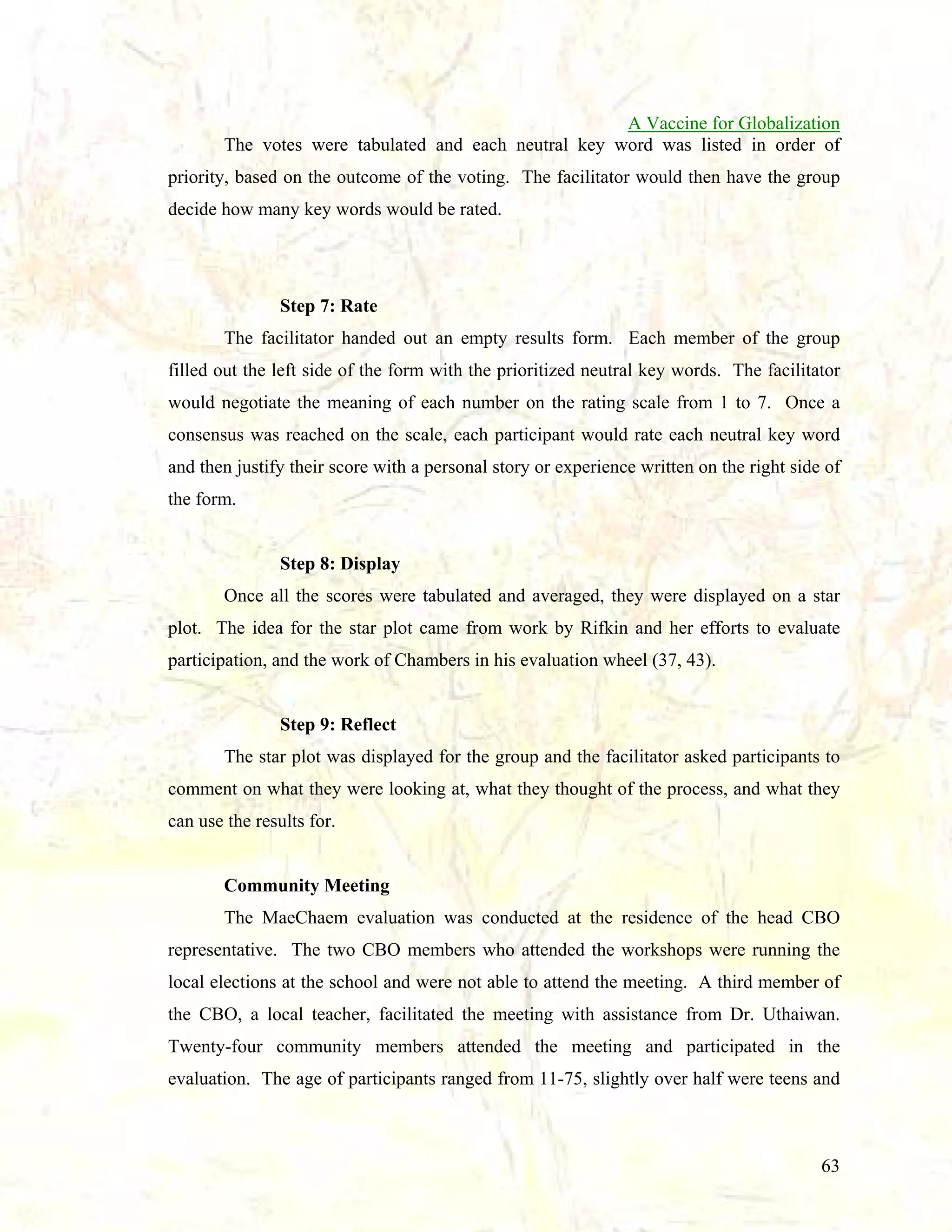

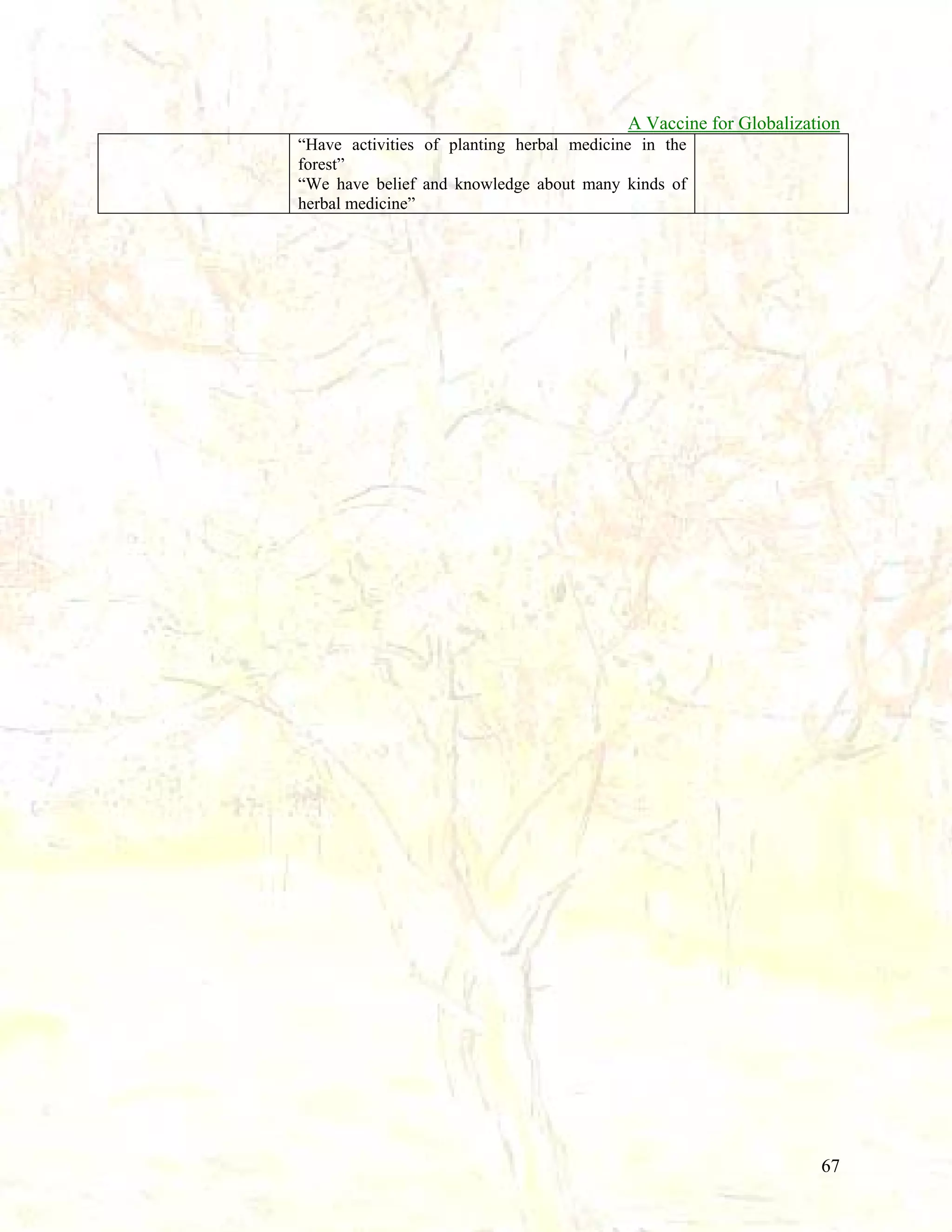

Table 2: Results of Step 6 - Prioritize all Categorizes identified through Steps 1 -5:

*(number of votes given to each Category in brackets):

Development Work

Growth

Cooperation (12)

Health

Unity (8)

Herbal Medicine Conservation (1)

Knowledge and Ability

Love and Happiness (2)

Travel

Massage activities

Traditional Culture

Amusement (1)

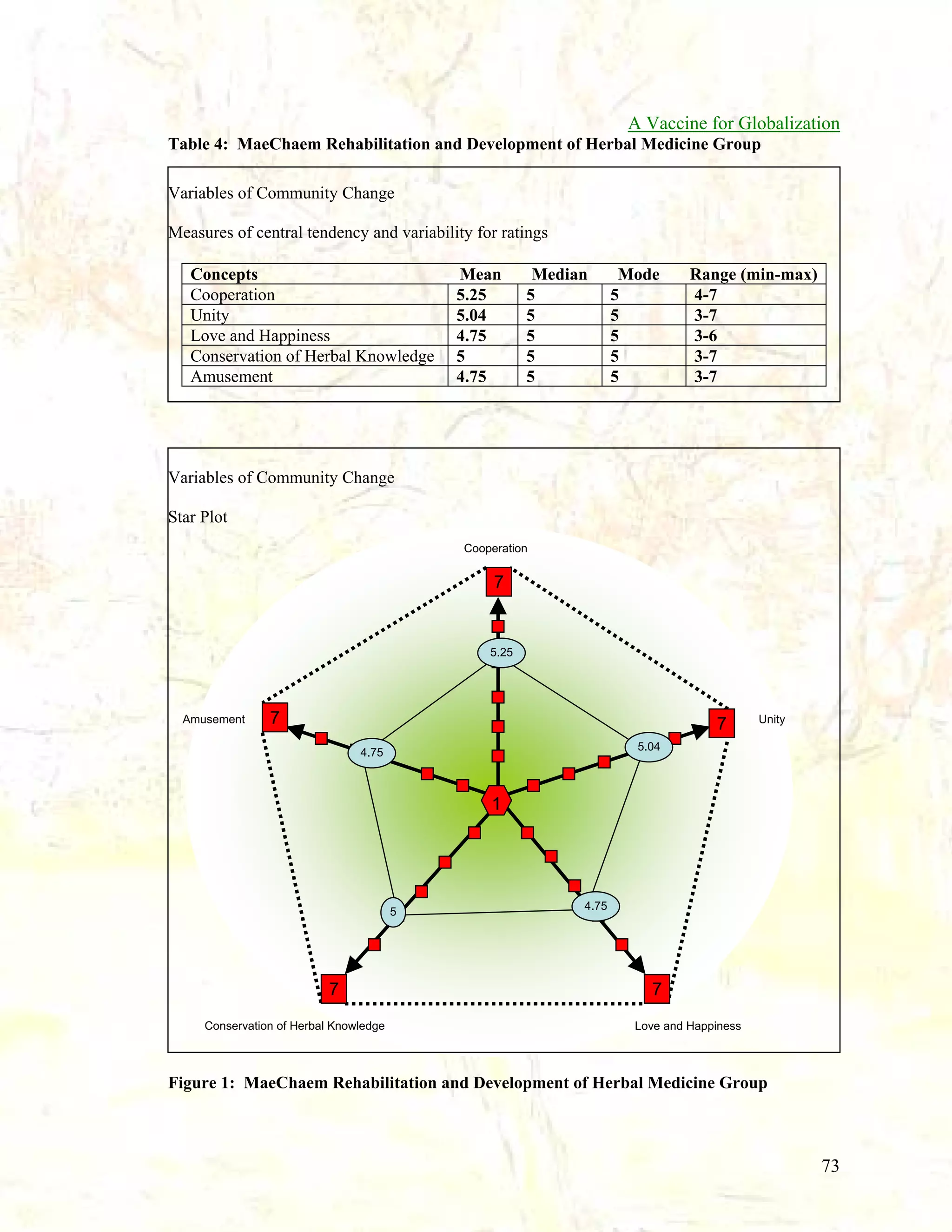

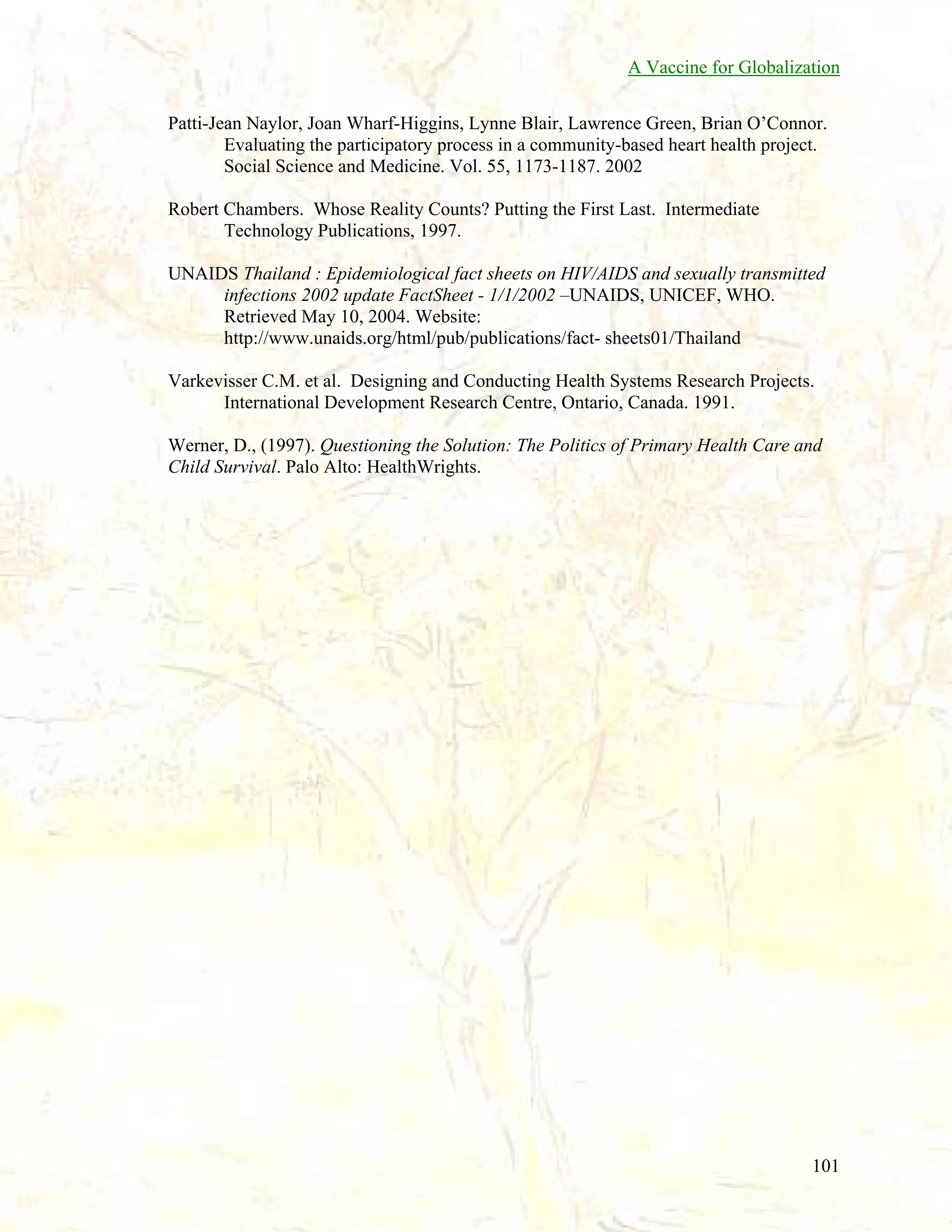

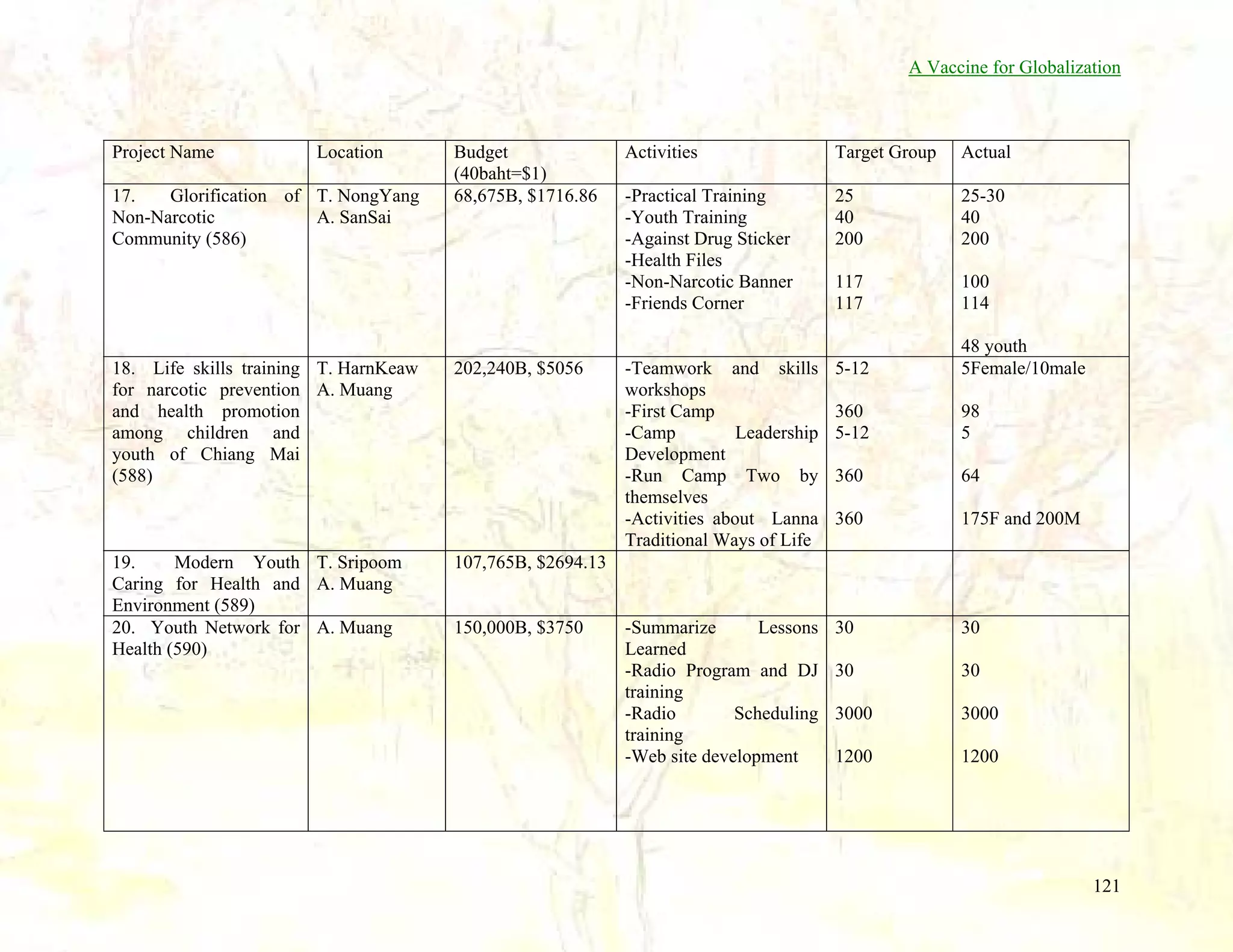

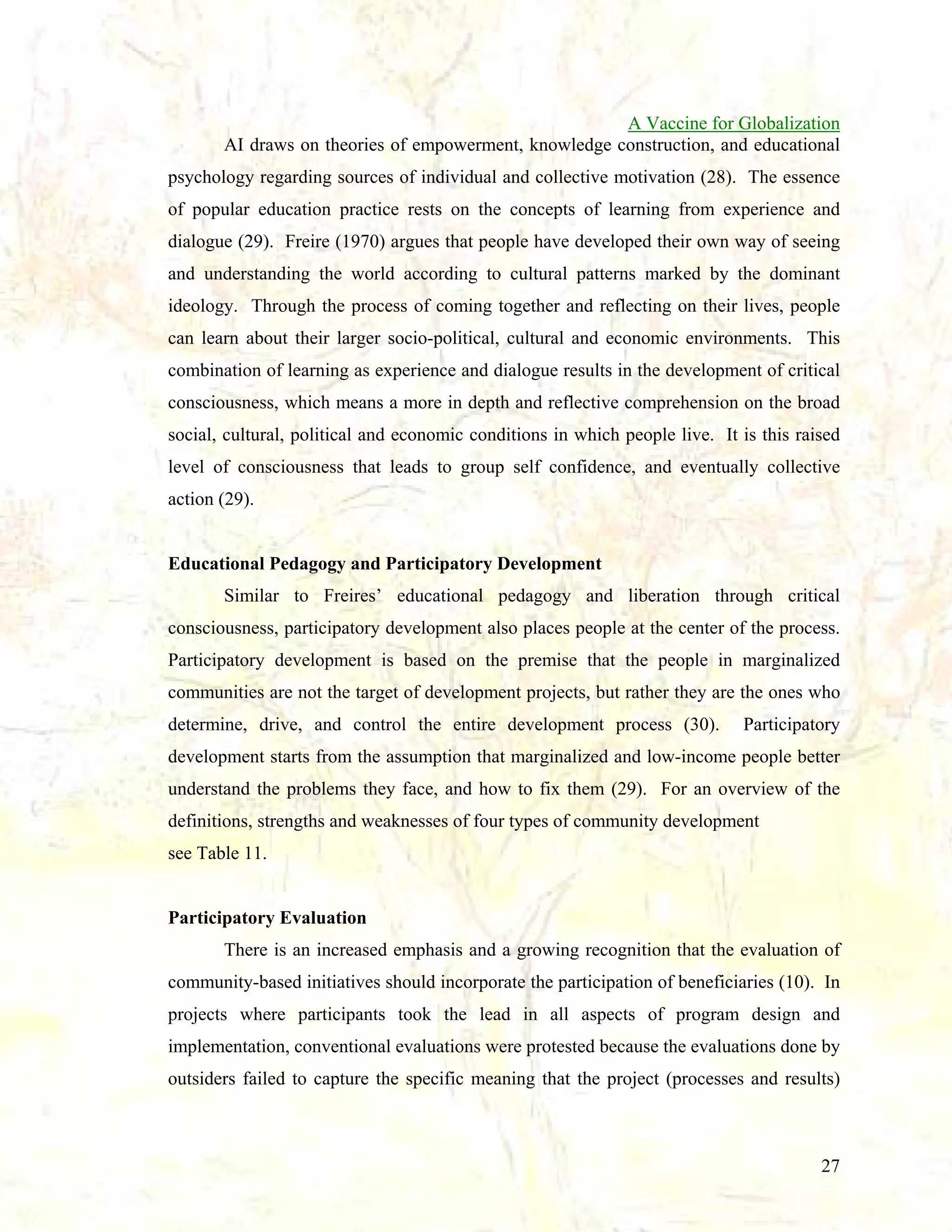

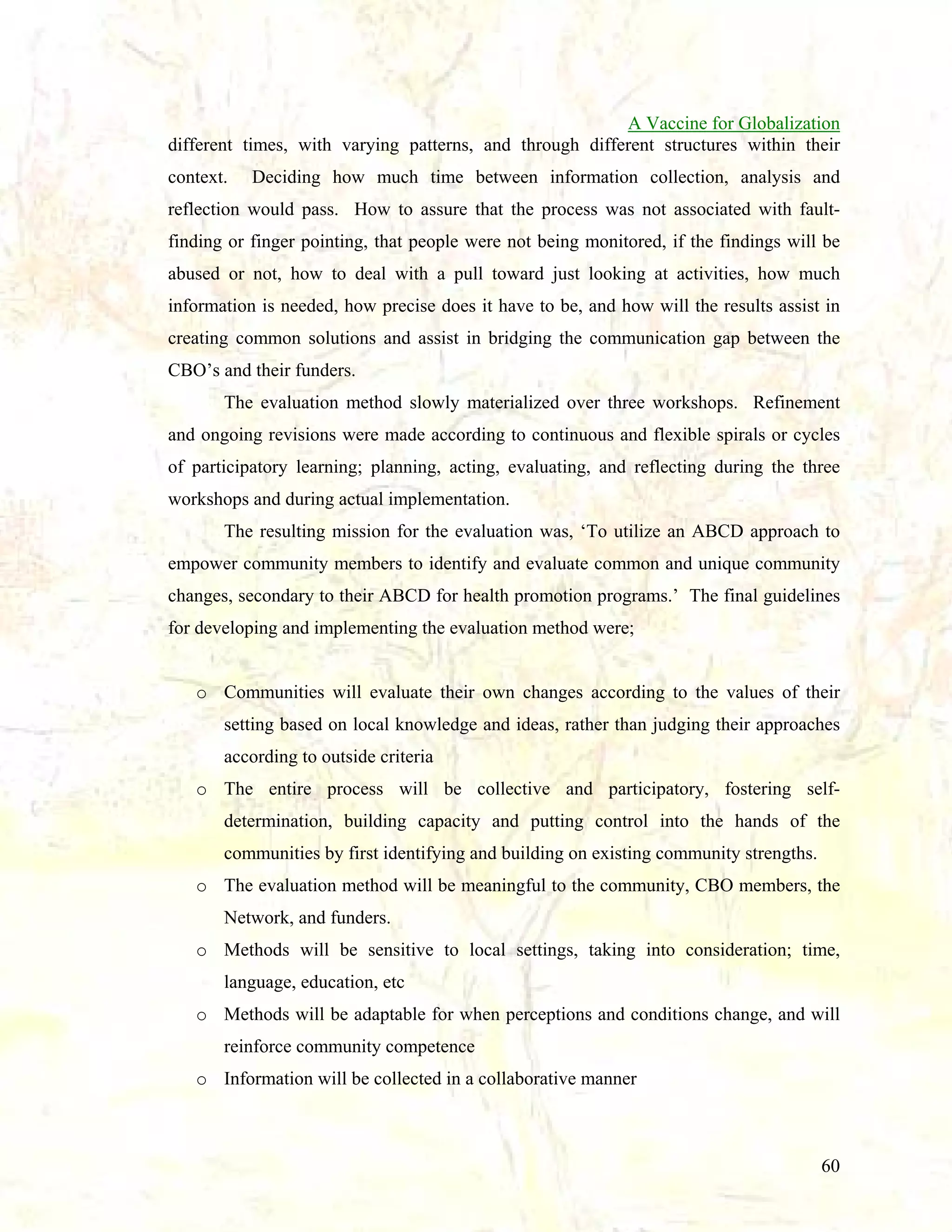

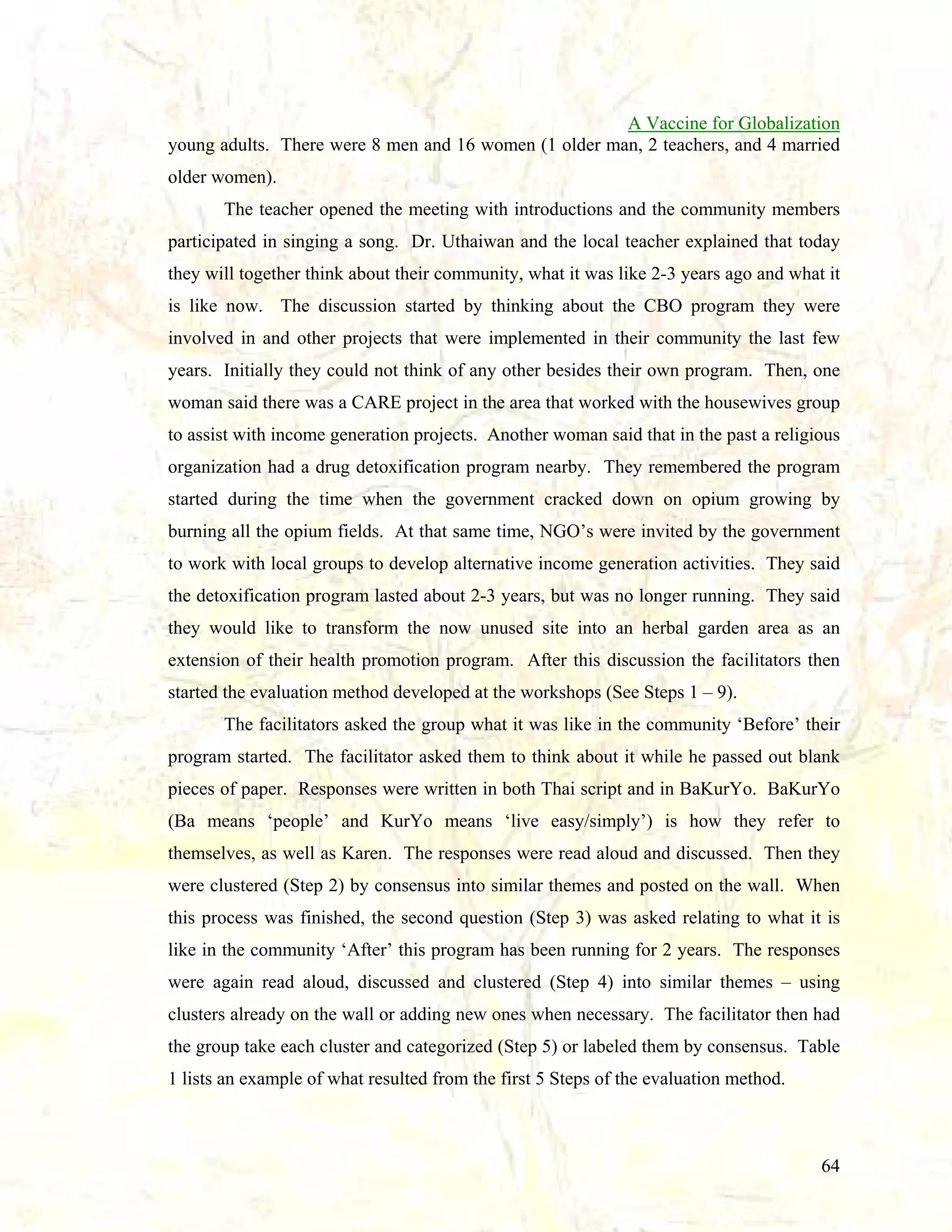

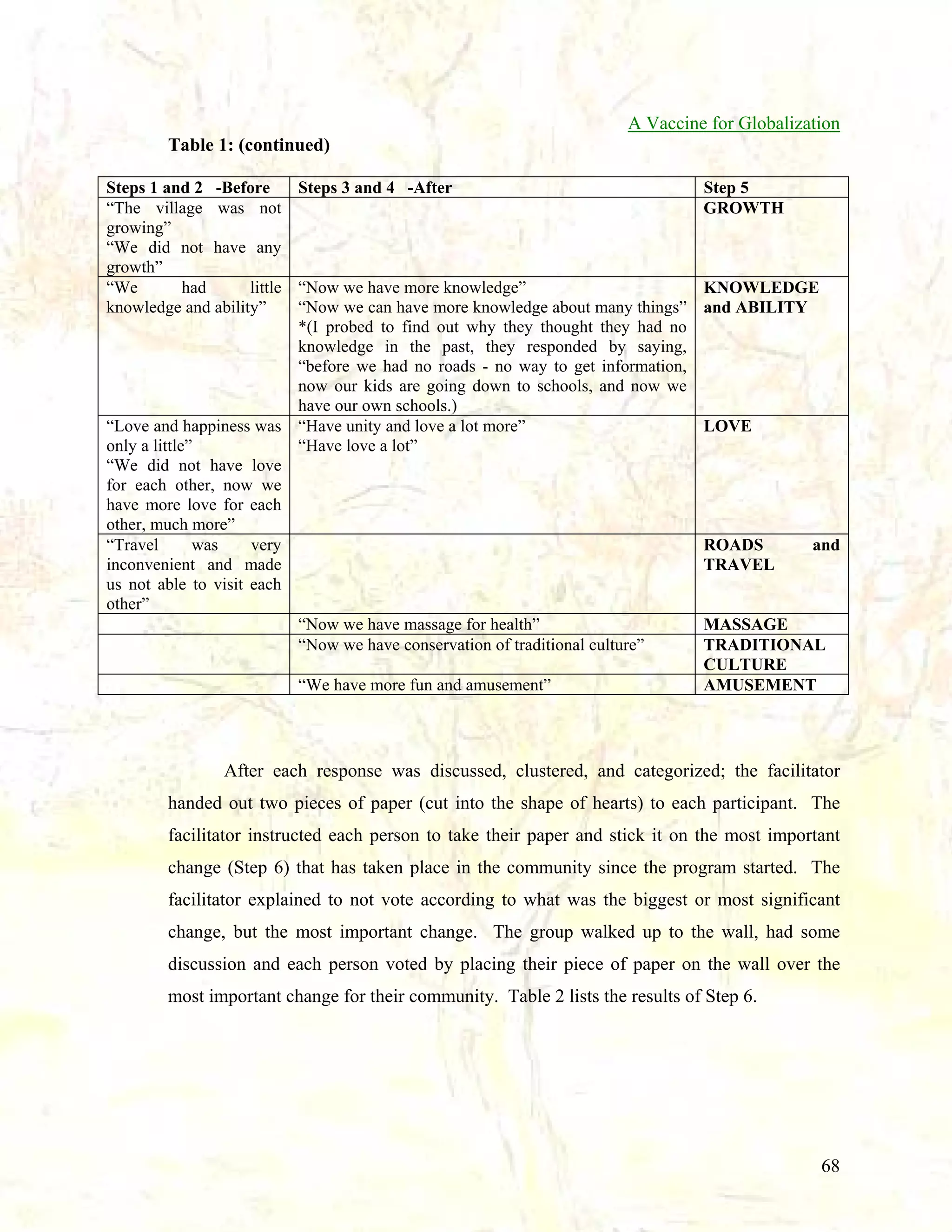

After the voting, the facilitator handed out a blank form and asked the group to rate,

on a scale of 1-7, how they thought the community was doing in regard to these changes

today (Step 7). The facilitator negotiated a definition for each number (1-7) and when the

group came to a consensus, they voted on the top 5 changes and were instructed to write a

story next to the score to justify their response.Table 3 lists the results from Step 7.

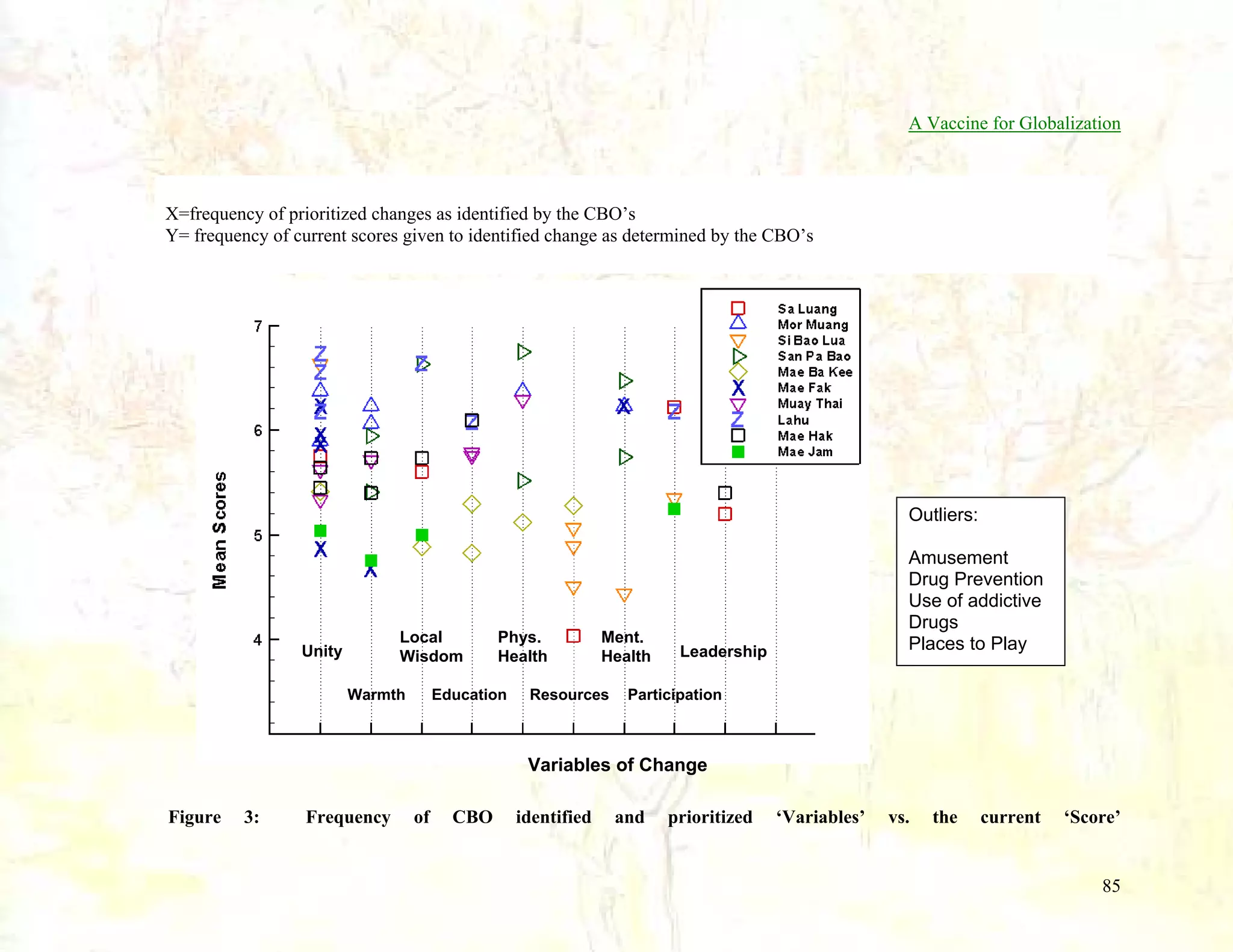

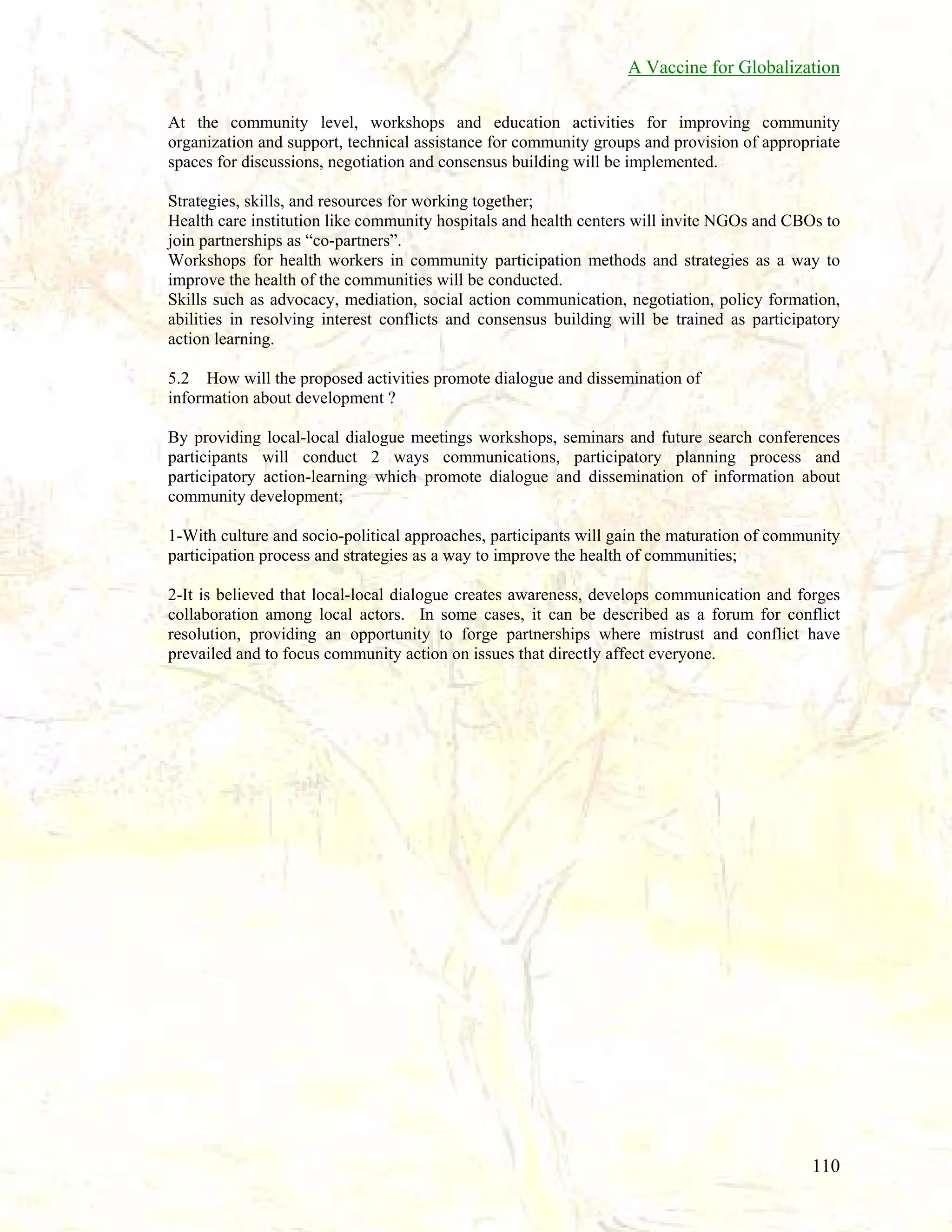

Table 3: Results of Step 7 - Rate the top 5 Categorizes followed by personal story to

justify each score:

*(score in brackets) *[number of times mentioned in brackets]

COOPERATION

(5) “When we have Christmas activities all of the villagers work together”

(4) “Have cooperation not a lot and not a little because we don’t give too much cooperation to

each other.”

(4) “Because we have work we help each other”

(4) “Have cooperation when we play sports”

(6) “Help each other cooperate”

(6) “Help to do”

(5) “Help each other work”

(6) “Cooperation for example when we build churches and schools”

(5) “Cooperation have more”

(5) “Working together”

(5) “Work to build church and school”

(6) “We have cooperation a lot better for example, working in groups”

(5) “Because we have good cooperation in building houses and working in the field”

(6) “Cooperation together for example building church and school”

(5) “For example in working to build the church and houses” [2]

(5) “Building a church and a school”

(6) “Building a church and a school”

(7) “It is the best thing”

(7) “It is the most important for Karen”

(5) “In village development”

69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a-globalization-vaccine-131020191807-phpapp01/75/A-Social-Vaccine-for-Globalization-Full-paper-70-2048.jpg)

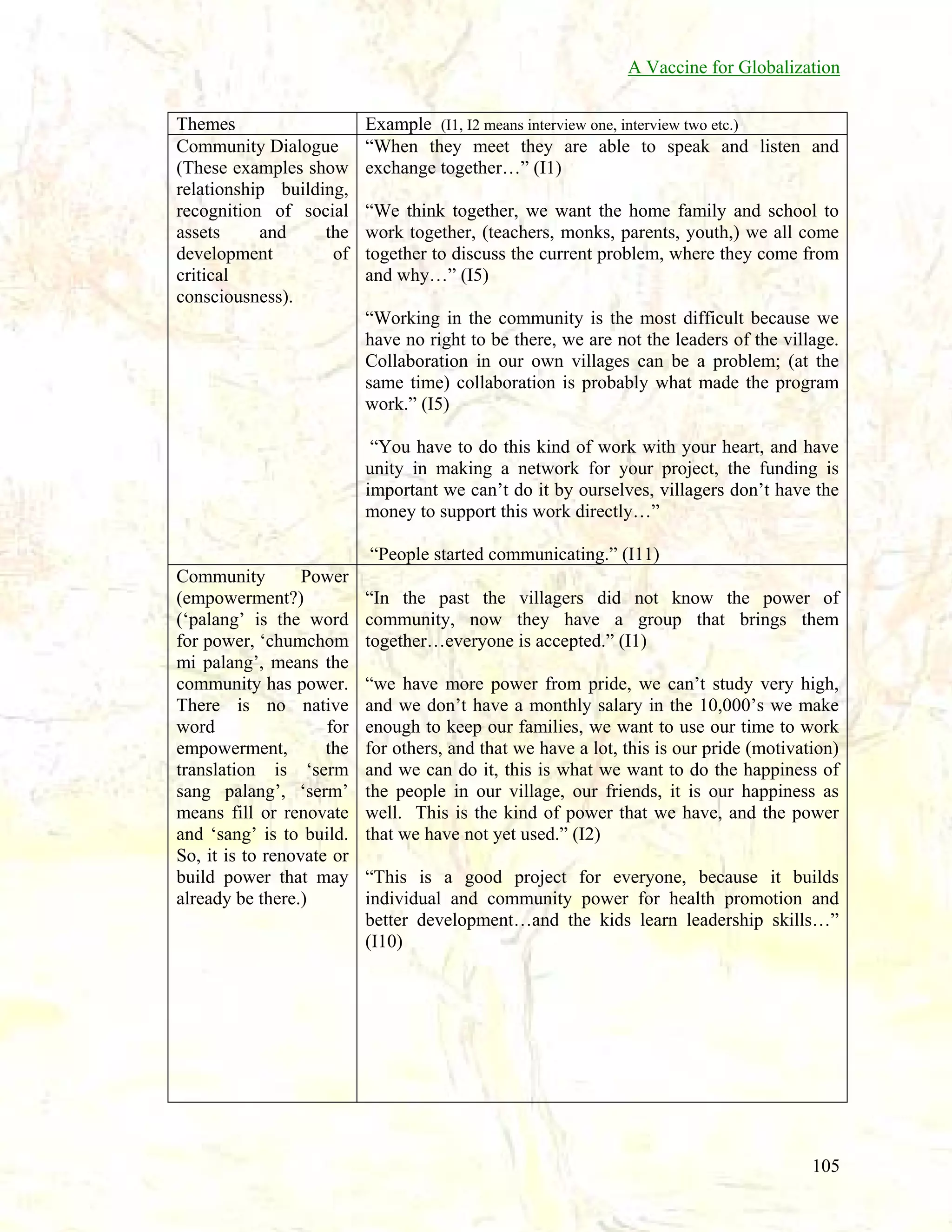

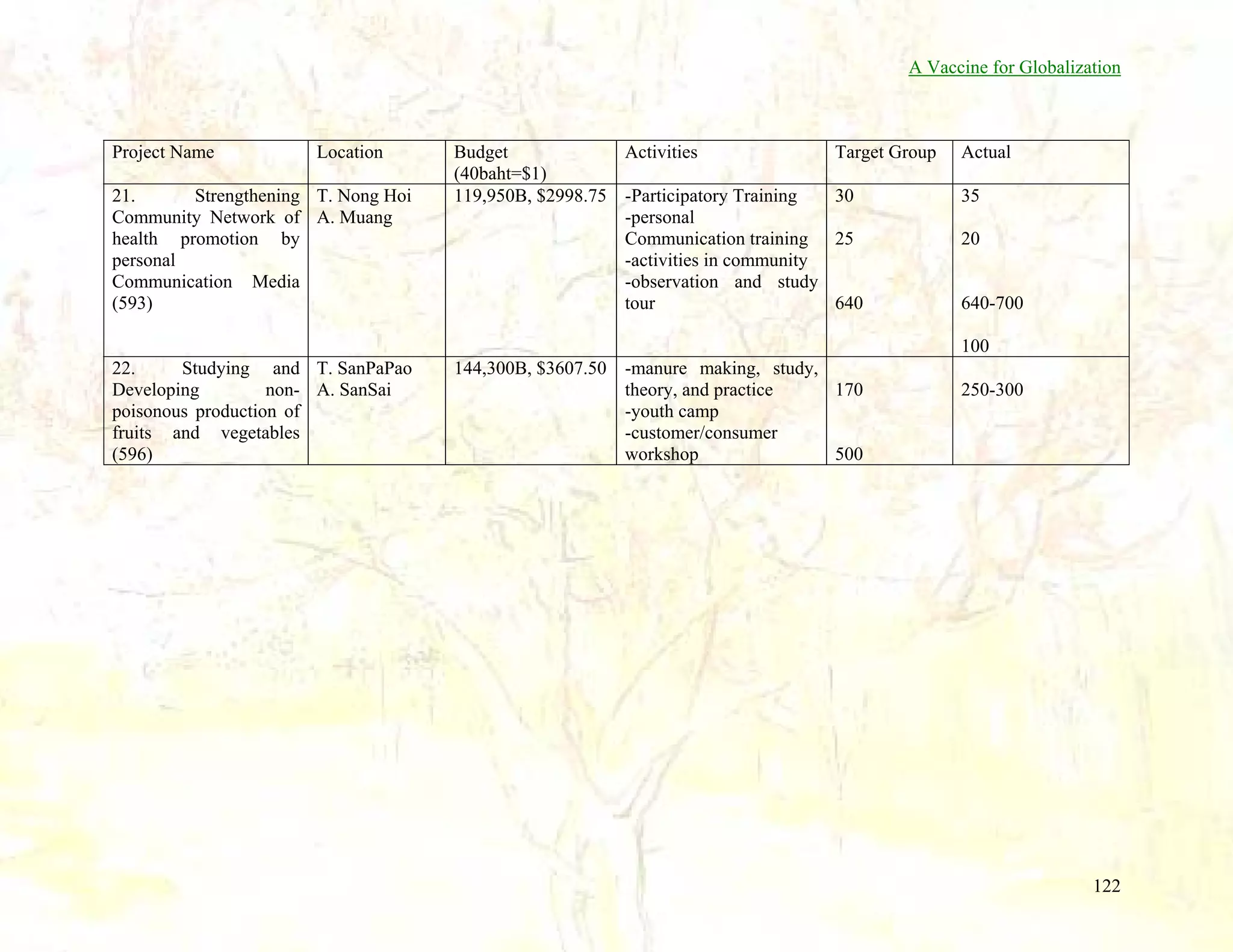

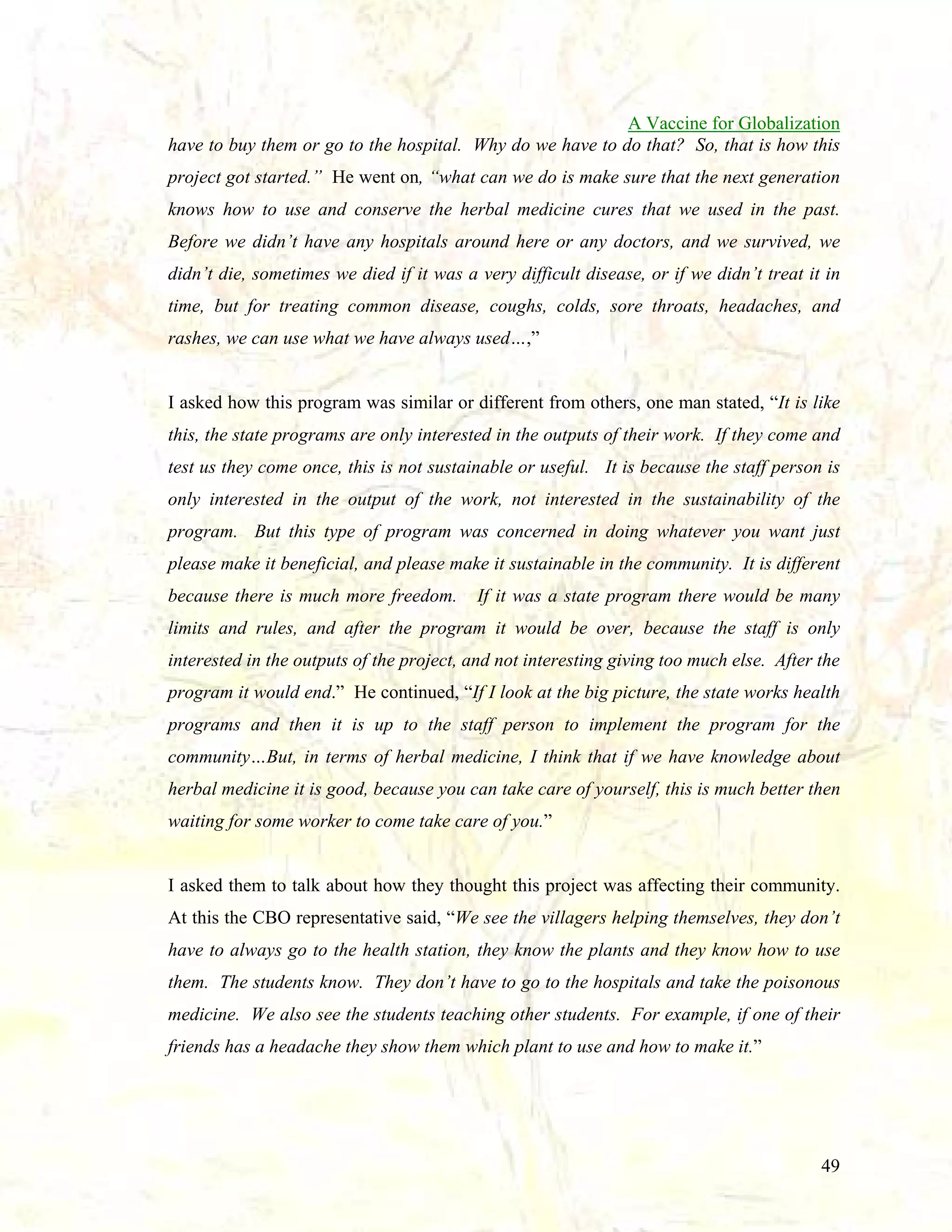

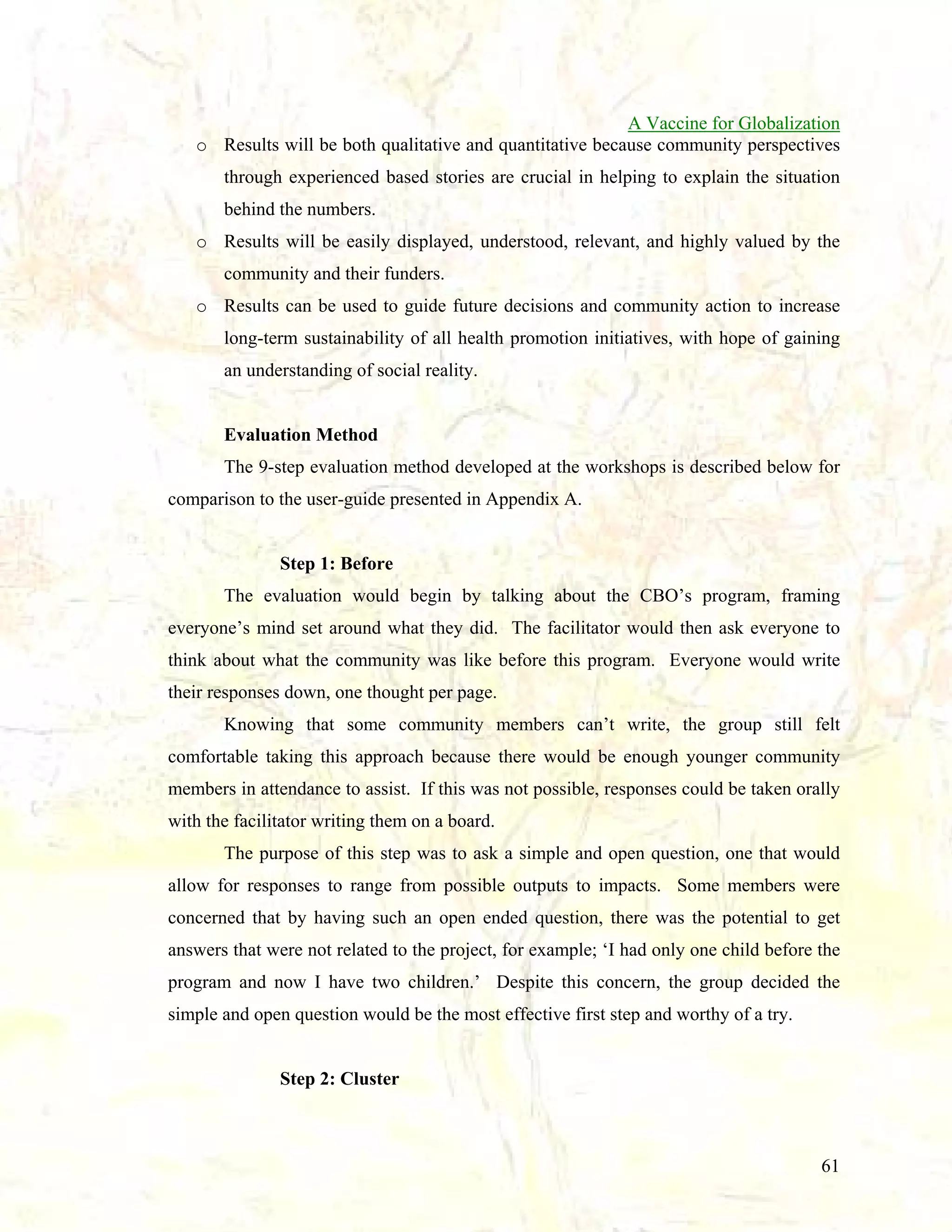

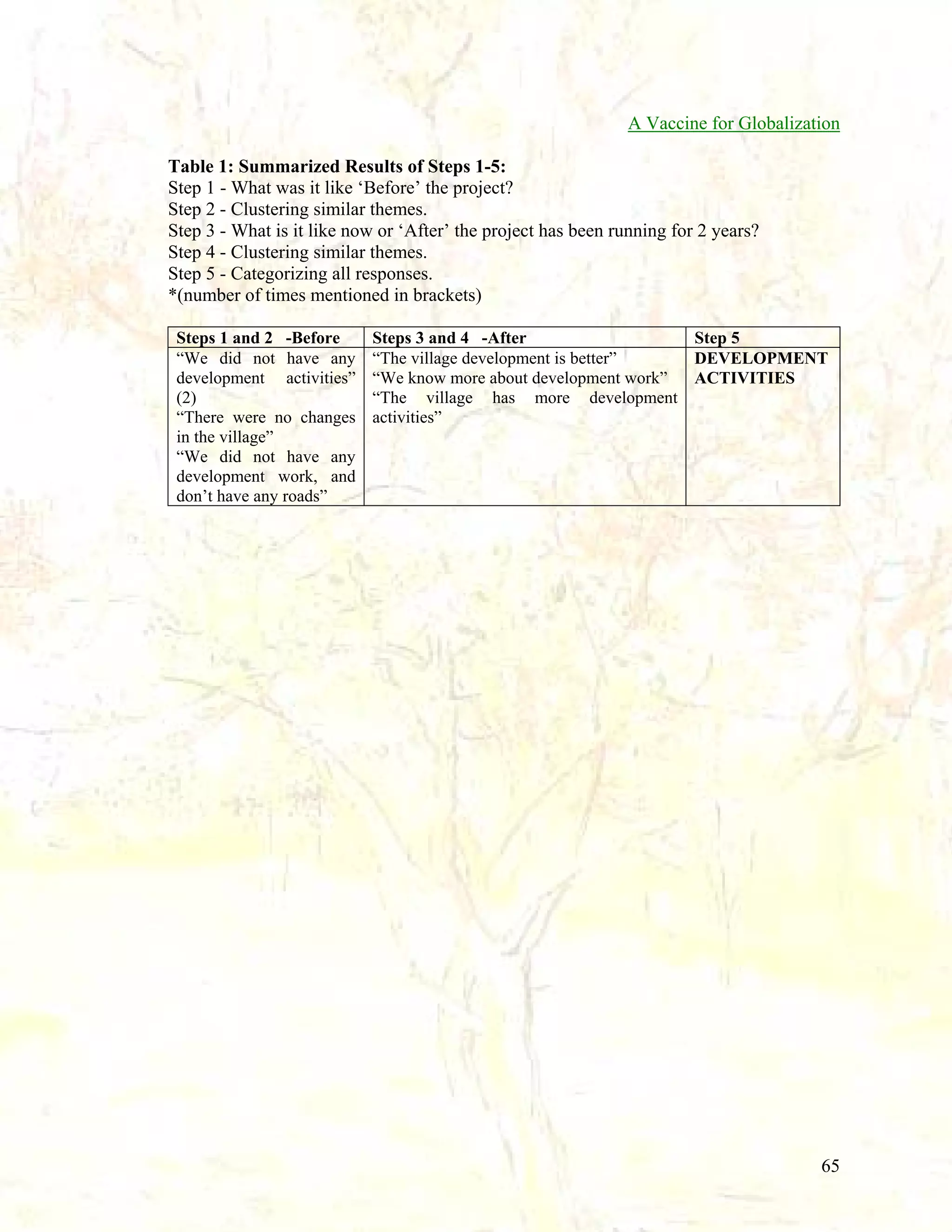

![A Vaccine for Globalization

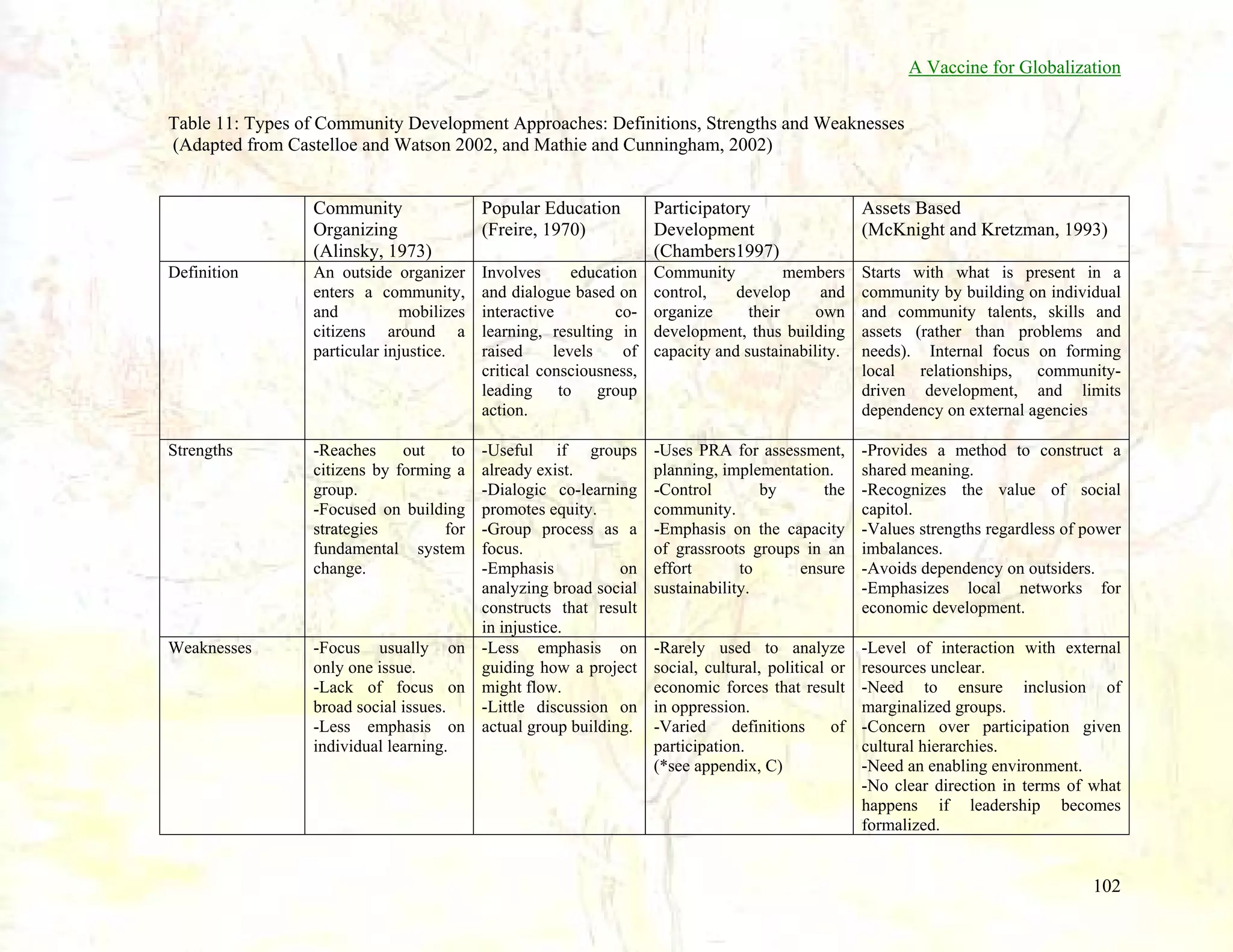

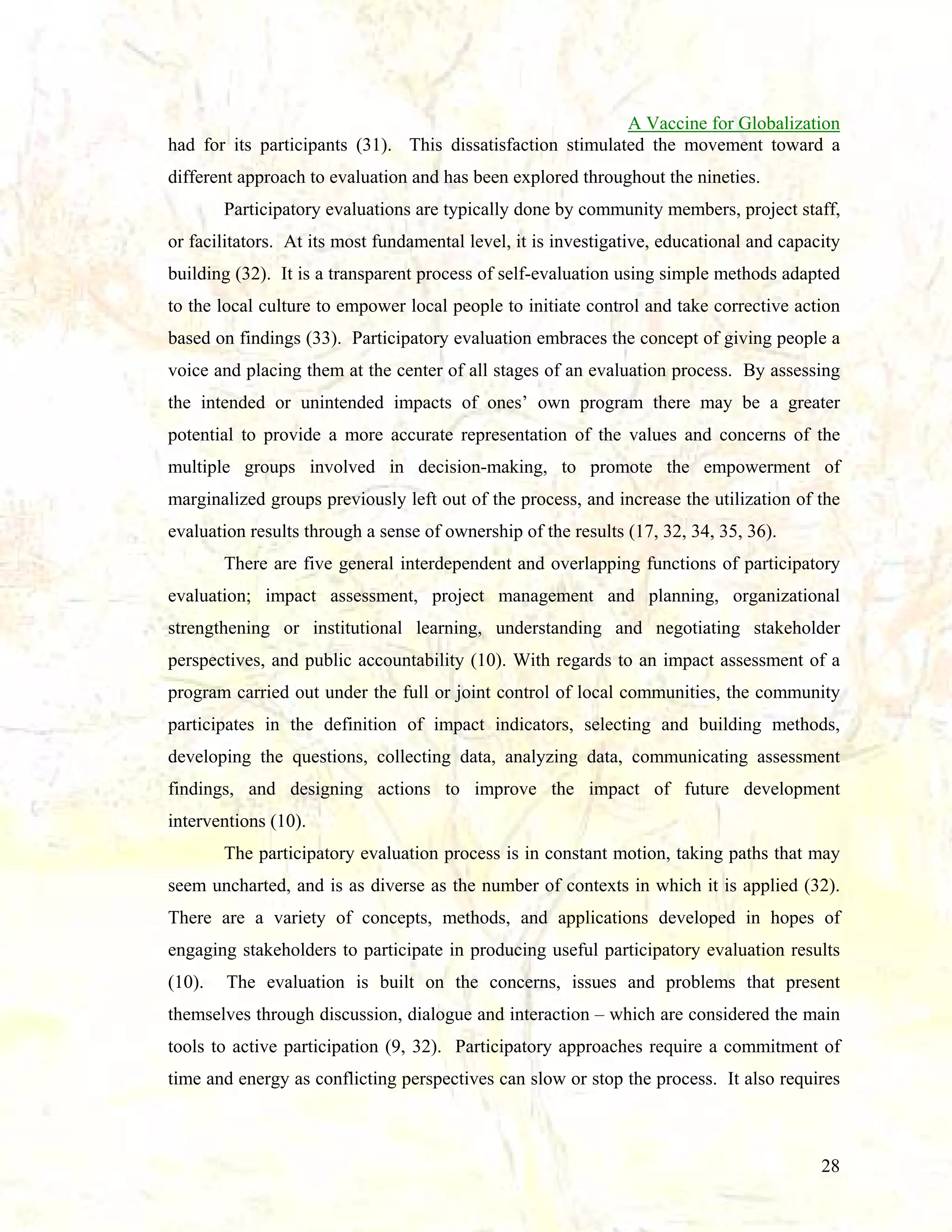

Table 3: (continued)

UNITY

(5) “On the 25th of the month we have group village meetings and we see everyone has a lot of

unity”

(5) “New Years activities and building new homes we have good unity”

(5) “If we have an activity we have unity more every time”

(5) “If we have sports we have good unity”

(4) “We help each other survive and have unity”

(5) “Help each other do activities”

(6) “We play sports activities”

(5) “For example the meeting on the 18th was very interesting”

(7) “We have more unity”

(7) “We all have to have unity together”

(6) “In the meeting everyone shows their interests in the community”

(3) “For example in the meeting we have only a few people”

(4) “Working in groups have unity”

(5) “Our meetings every month show the interests of the community”

(5) “In the village meeting the community is very interested”

(4) “For example at Christmas we have good unity”

(6) “We work together”

(5) “We have unity in many activities”

(6) “We know each other more”

(6) “Unity of the community is better, love and unity together is better”

(4) “Have more unity”

LOVE

(4) “When one person in the village does a good thing we all see and are glad and let them

know”

(5) “We understand each other”

(5) “Peek at love”

(6) “Love each other a lot”

(5) “Love each other in the community”

(5) “Have active compassion sharing and love”

(5) “Getting along well, show our affection for each other”

(5) “We have more love”

(5) “Love is beneficial for us”

(5) “Have love for each other”

(3) “Love not a lot because not have enough knowledge”

(5) “Love for each other”

(4) “We help each other” [2]

(5) “We help each other” [2]

(6) “We help each other”

(5) “Makes us know and endure more”

(5) “The love of the village is better”

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a-globalization-vaccine-131020191807-phpapp01/75/A-Social-Vaccine-for-Globalization-Full-paper-71-2048.jpg)

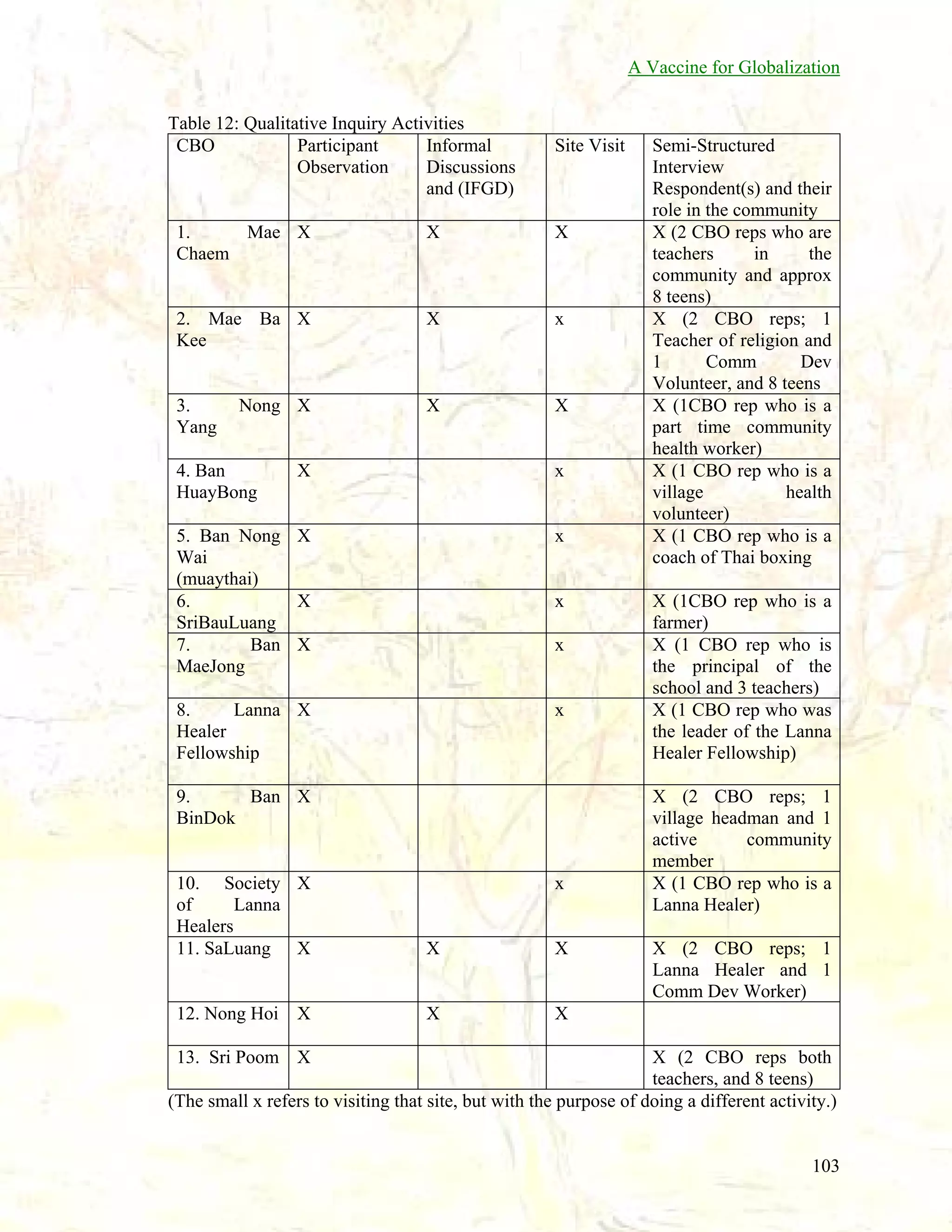

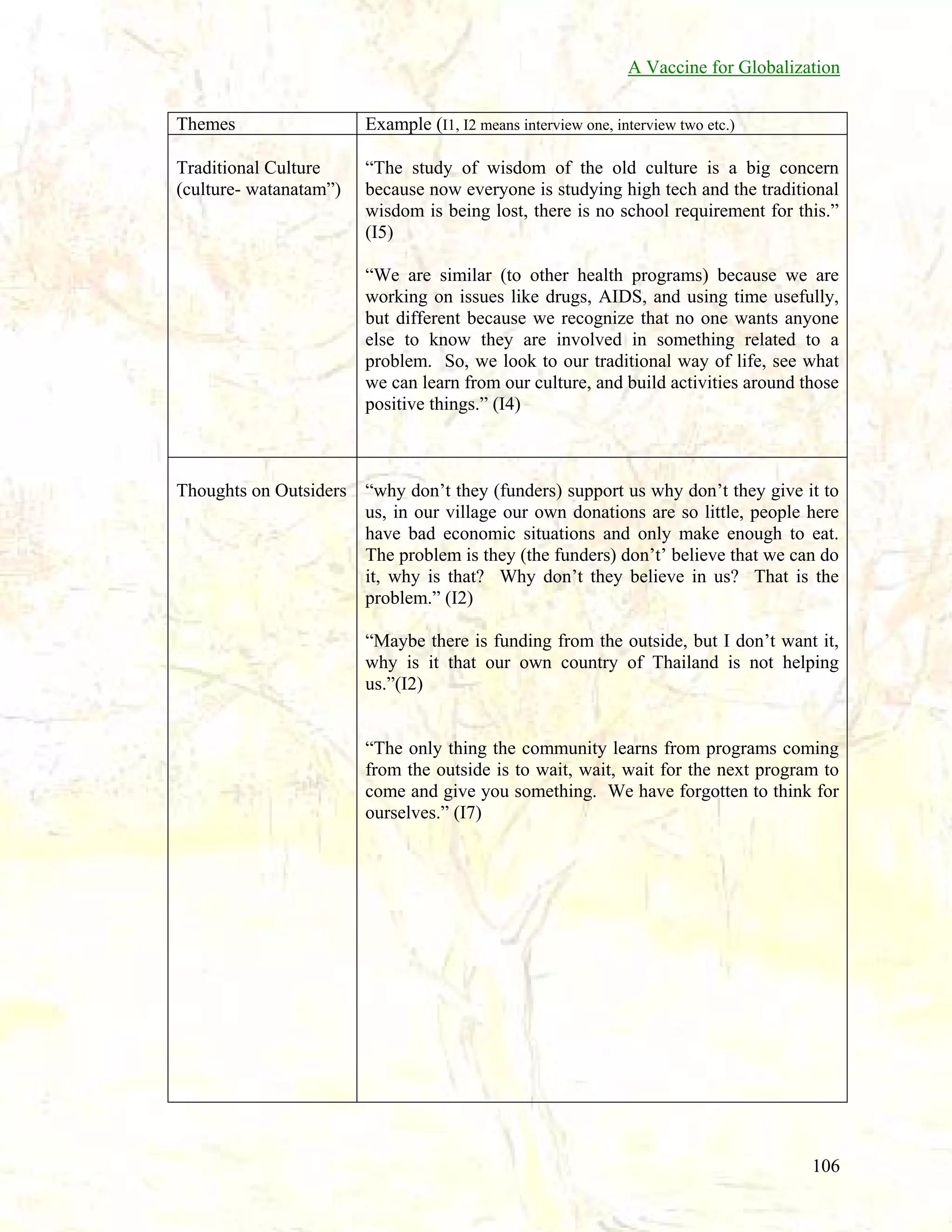

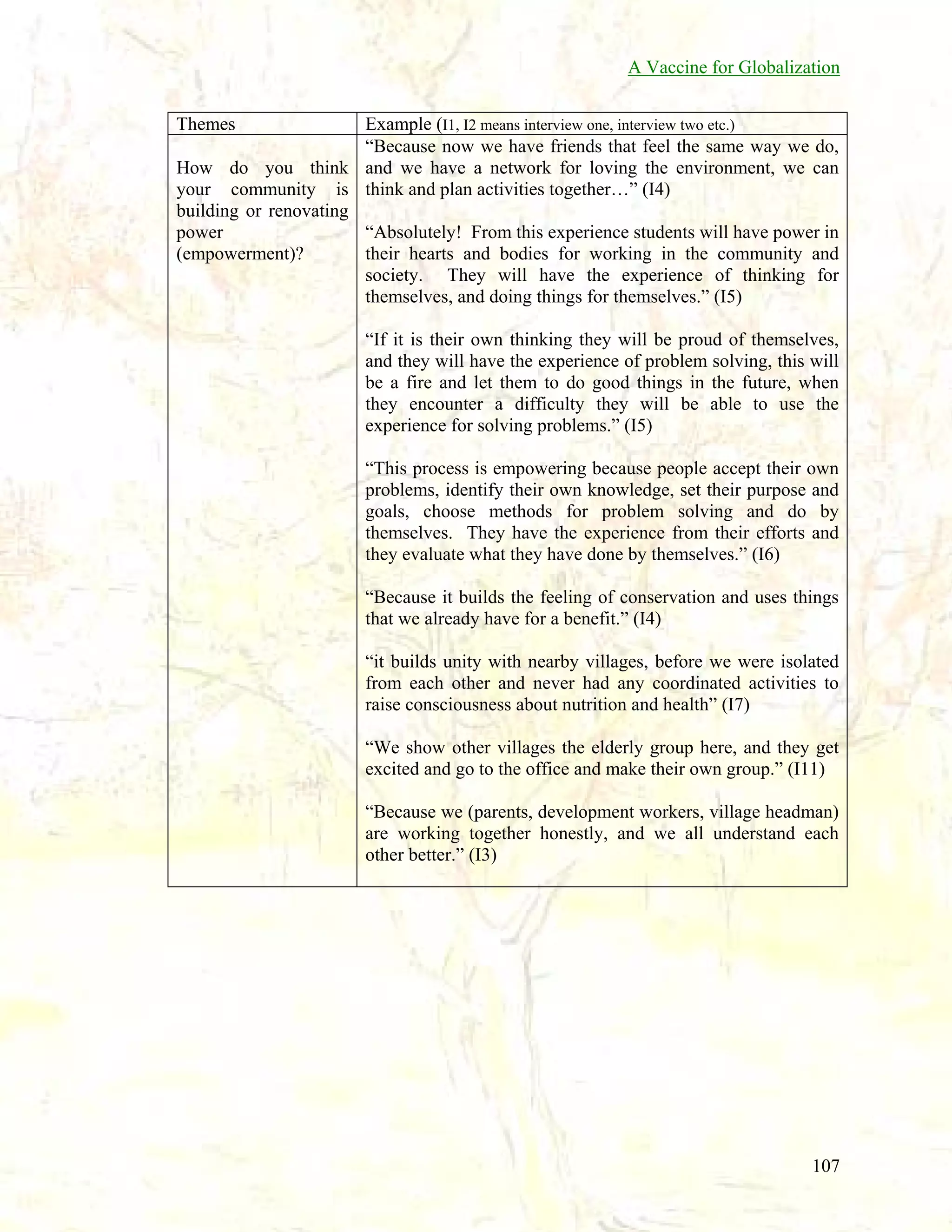

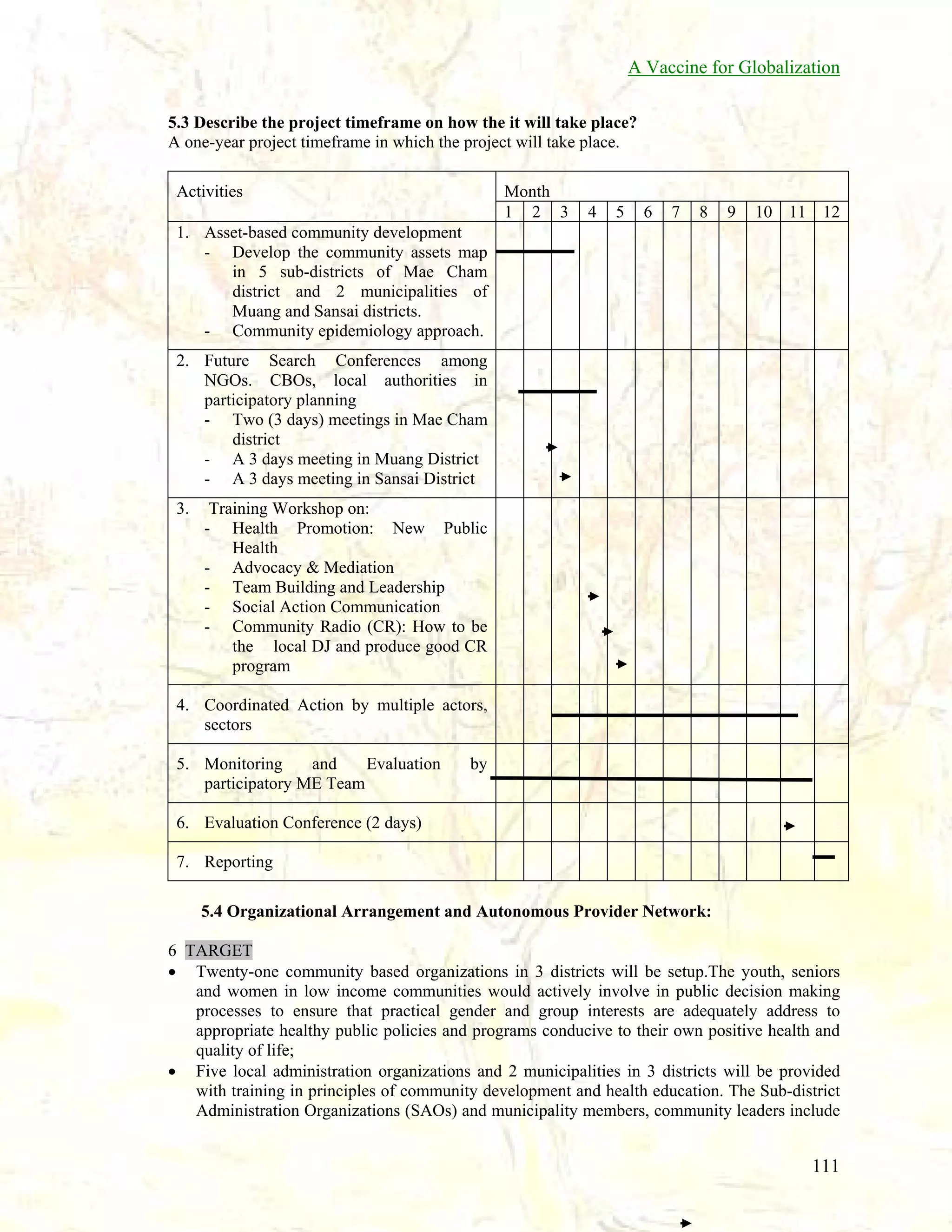

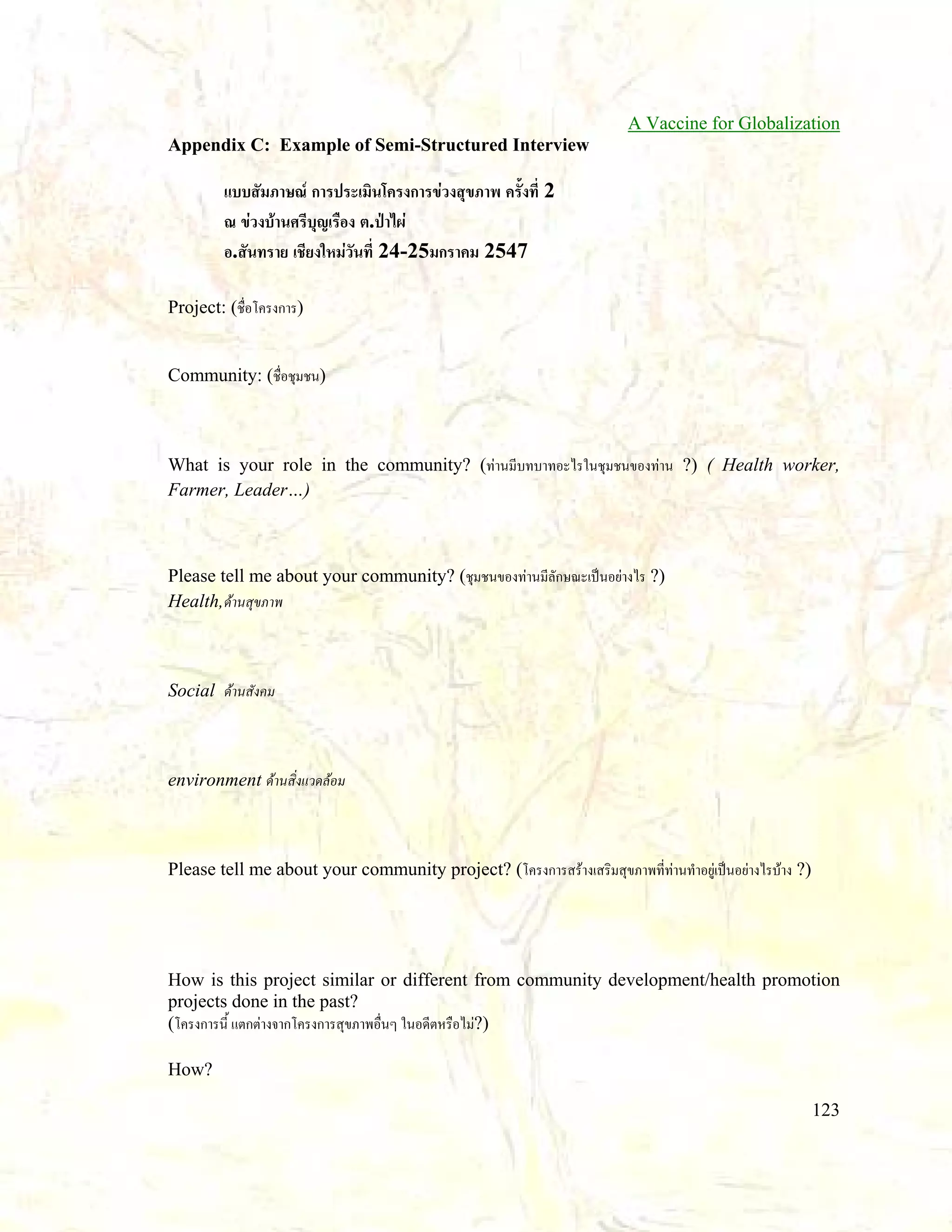

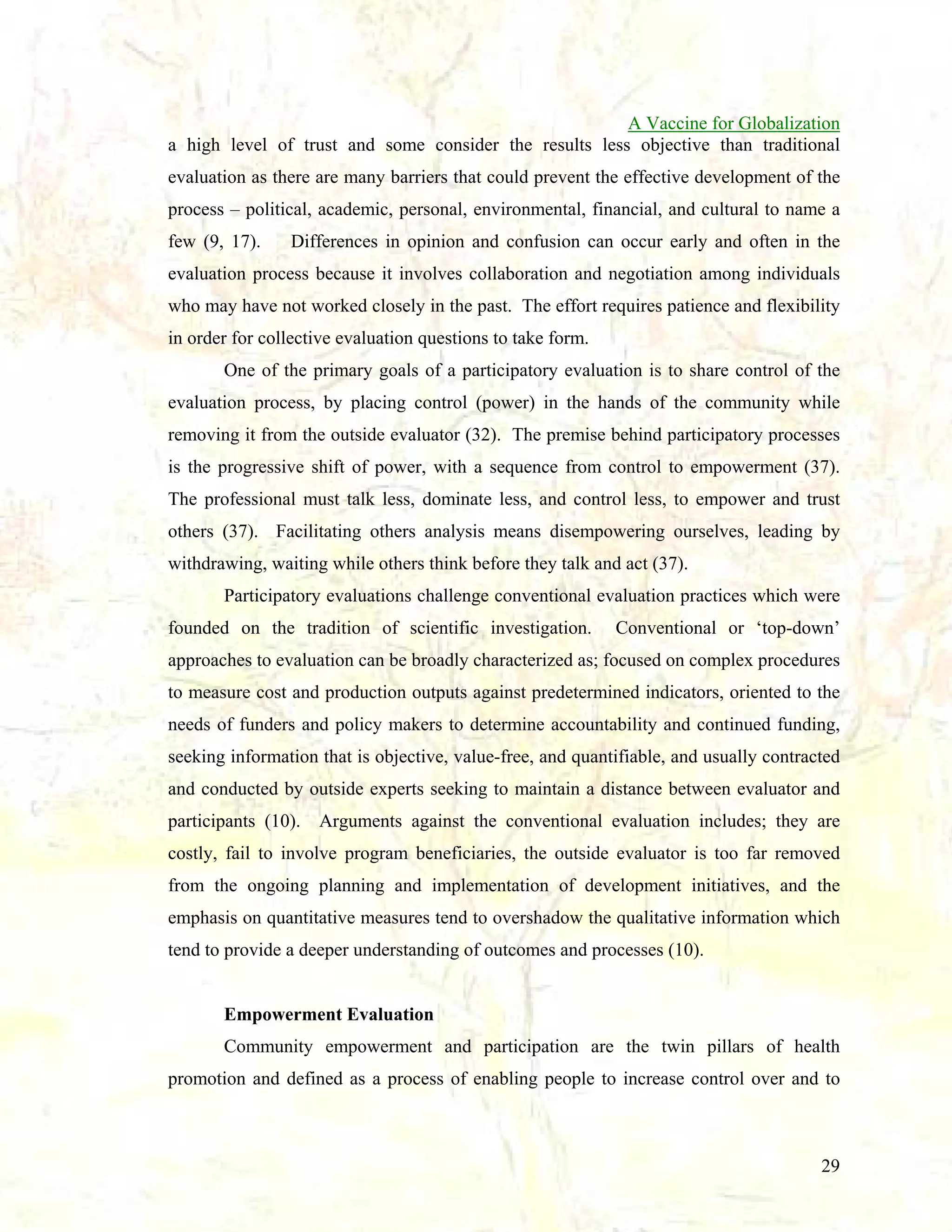

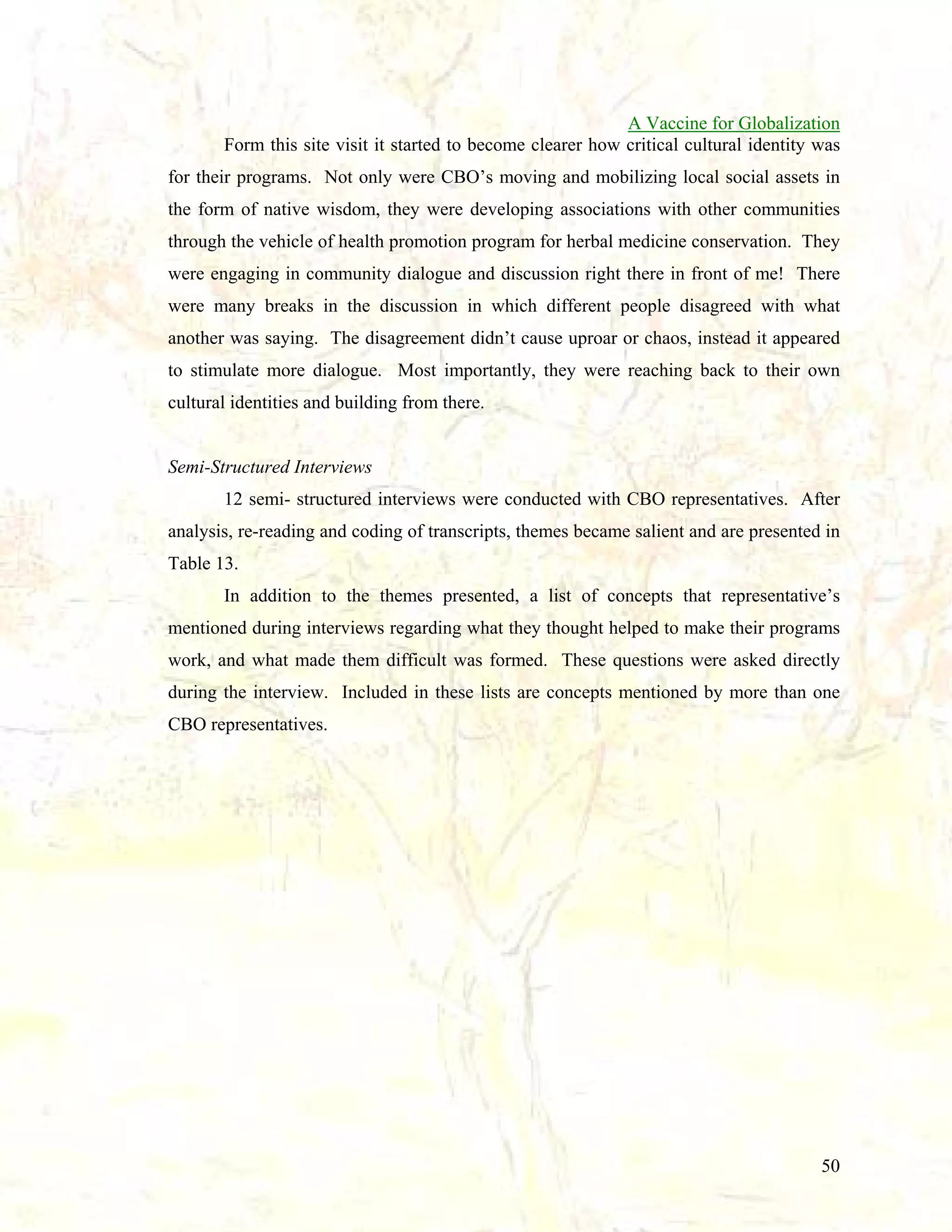

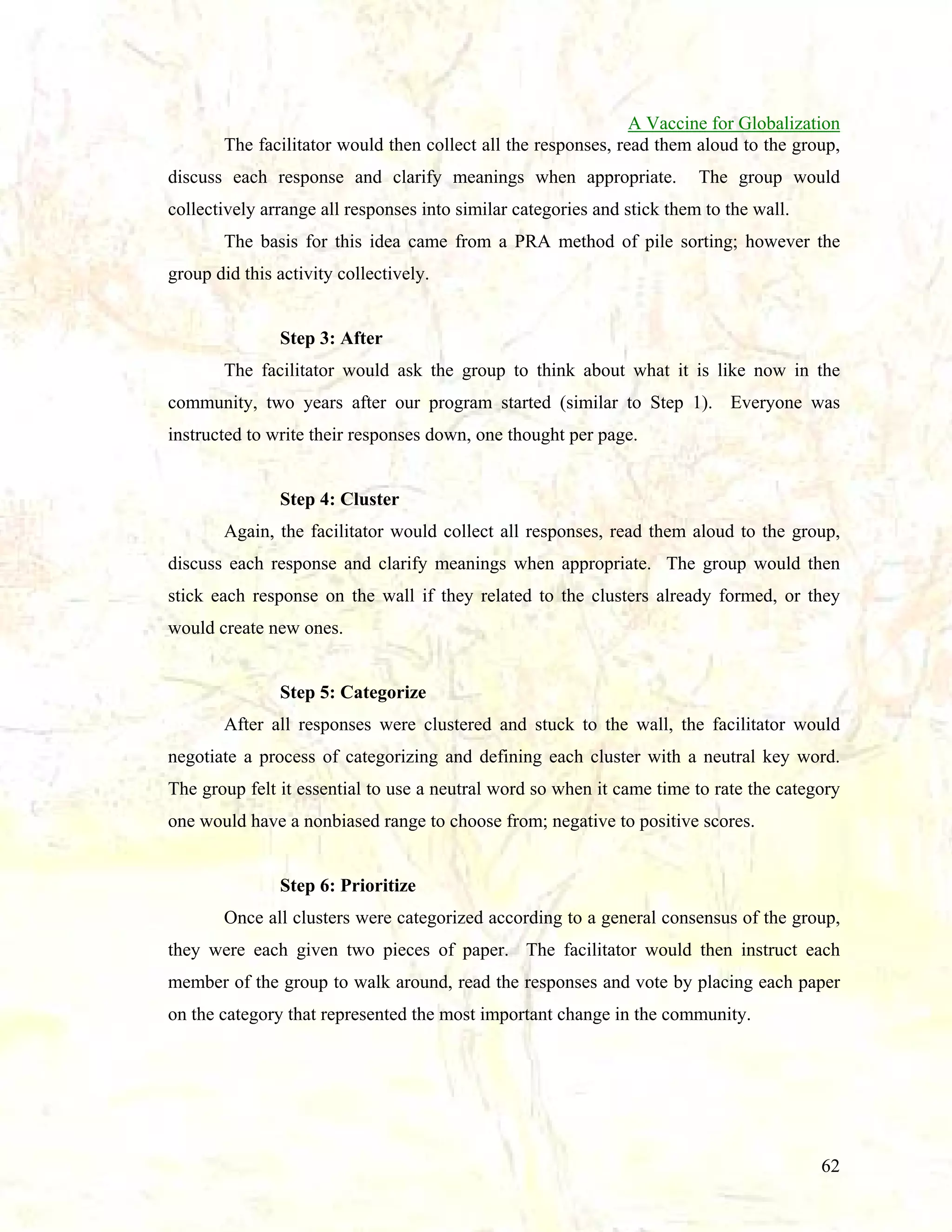

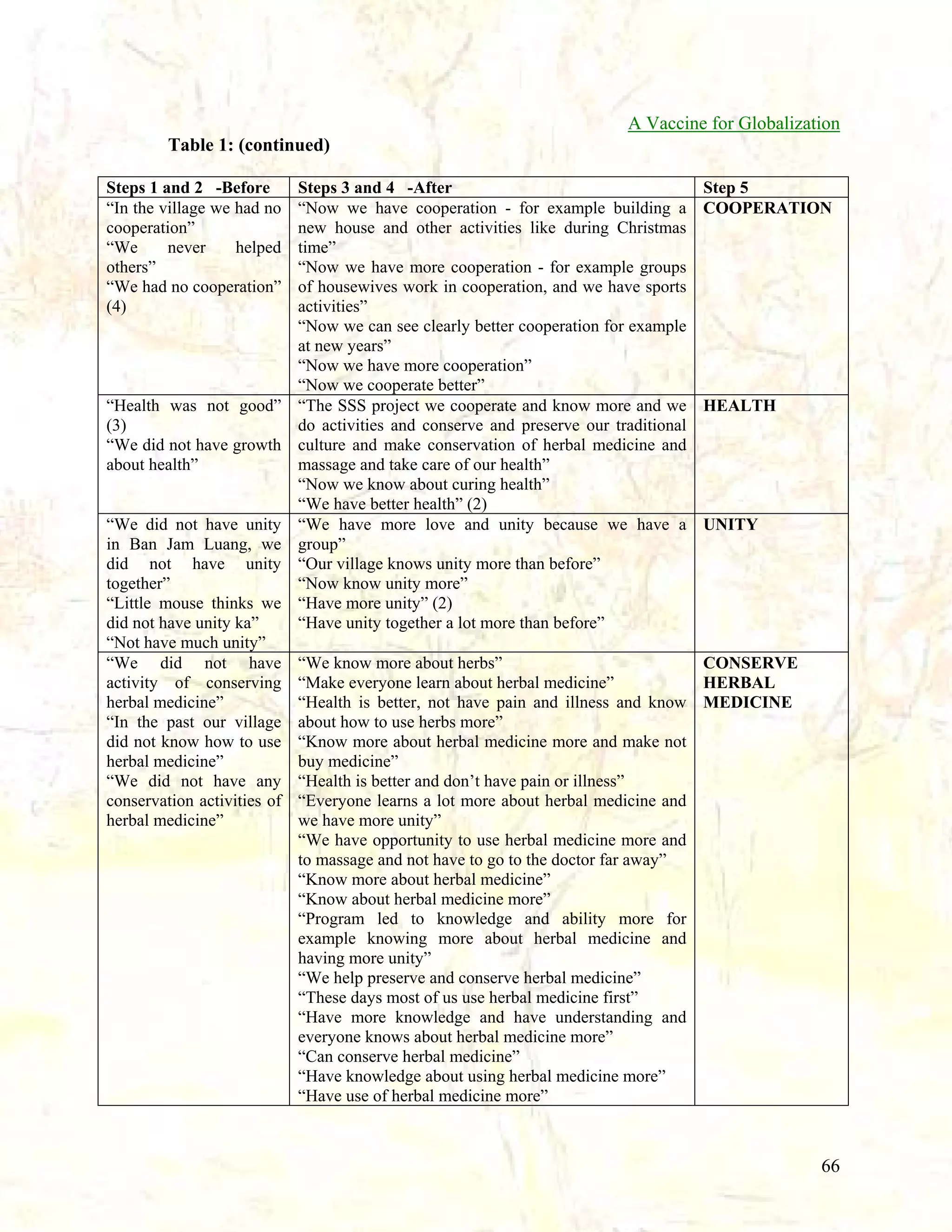

![A Vaccine for Globalization

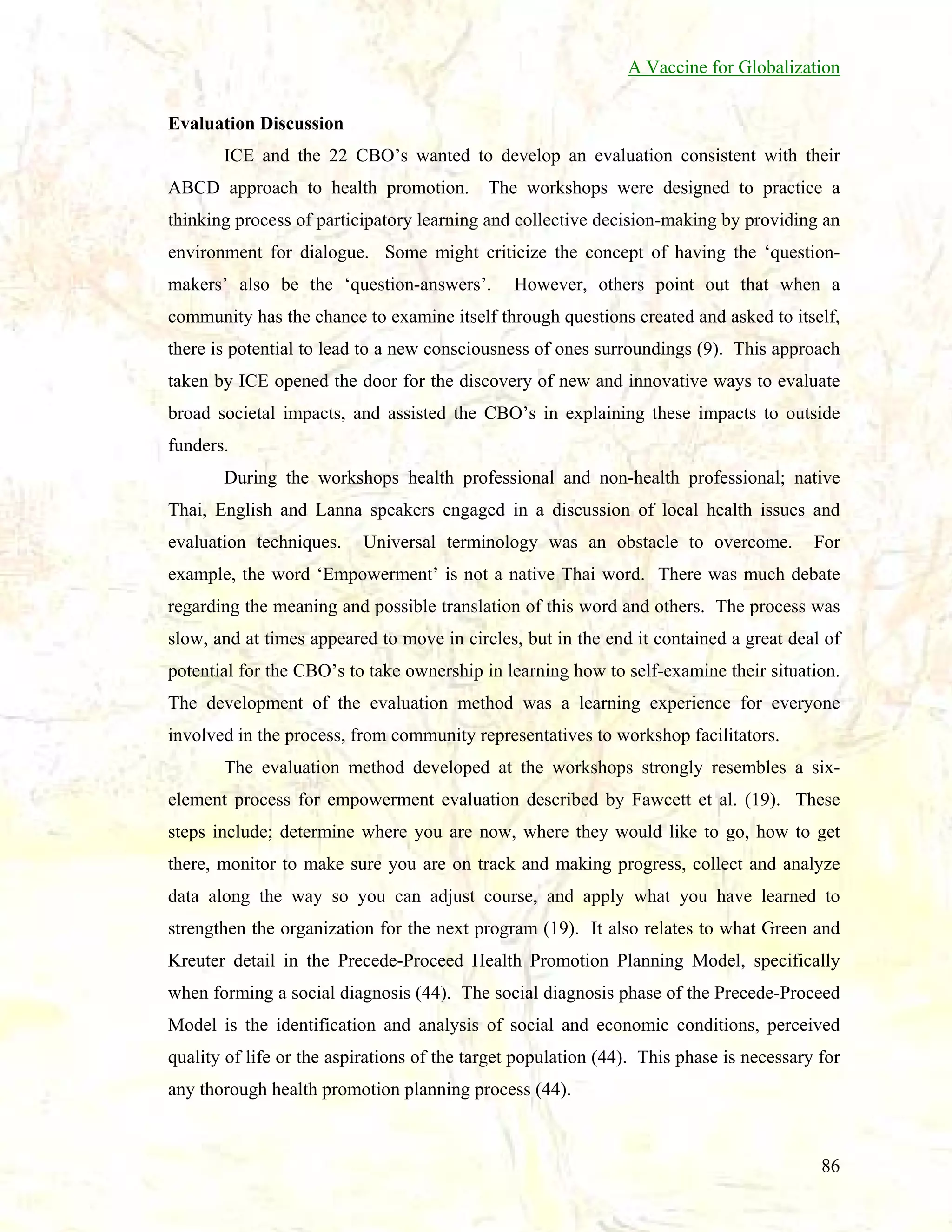

Table 3: (continued)

CONSERVATION OF HERBAL MEDICINE WISDOM

(5) “Conservation of the herbal medicine for example making a place for the conservation of

herbal medicine (in the forest)”

(5) “When we make a space and study herbal medicine conservation in the forest”

(6) “If we are not comfortable we can use herbal medicine, we should conserve herbal

medicine”

(6) “Because we don’t have to go buy medicine”

(5) “Conservation of herbal medicine”

(7) “Herbs are medicine”

(4) “It is medicine we can eat”

(5) “Now we know how to use herbal medicine”

(4) “Conservation of water and the forest”

(6) “Development activities of herbal medicine”

(6) “Using herbal medicine is very beneficial us”

(4) “We need to conserve herbal medicine for the kids and relatives because it is

beneficial/useful for use”

(3) “Activities to conserve herbal medicine”

(5) “Conservation of herbal medicine to save and make more”

(5) “We are conserving herbal medicine for the benefit of all of us and all of our kids and

relations always”

(5) “Conservation of herbal medicine”

(4) “Some people take medicine from the hospital and don’t get well, then they take herbal

medicine and get better”

(5) “We will conserve herbal medicine”

(6) “Conservation of herbal medicine is very important for the people who are far away from

the doctor”

(6) “Want the conservation of herbal medicine to be sustainable”

(5) “Want to use herbal medicine and want it to be sustainable”

AMUSEMENT (FUN)

(3) “When we have sports we go to give support”

(5) “For example playing sports is having fun”

(4) “For example we play sports and have fun”

(4) “Help each other play football”

(7) “Play sports”

(4) “Play sports” [2]

(5) “Plan activities all kinds”

(4) “For example takraw”

(5) “Play sports” [3]

(5) “Play sports is a lot of fun”

(5) “For example at Christmas we have sports”

(6) “We have fun always”

(5) “Christmas and sports” [3]

(5) “Makes us happy - think well of each other”

(4) “Christmas and sports”

(5) “Play sports and Christmas”

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a-globalization-vaccine-131020191807-phpapp01/75/A-Social-Vaccine-for-Globalization-Full-paper-72-2048.jpg)