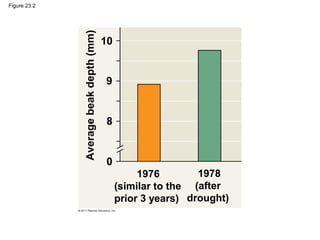

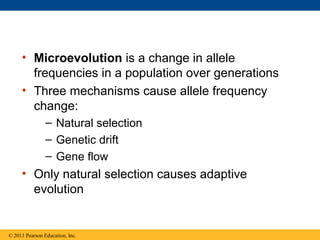

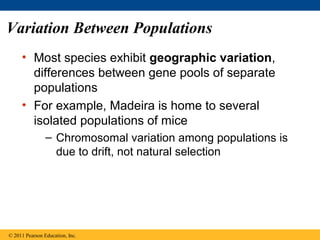

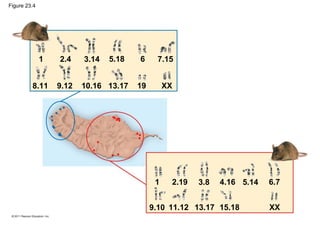

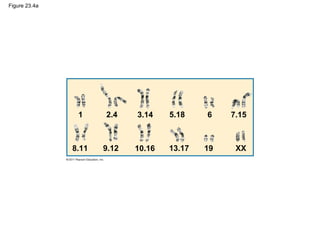

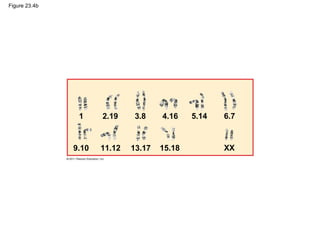

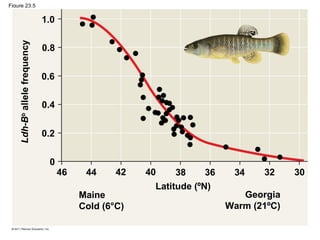

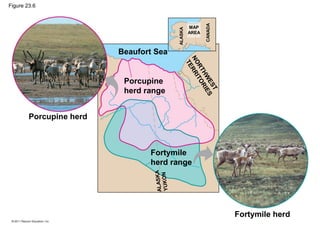

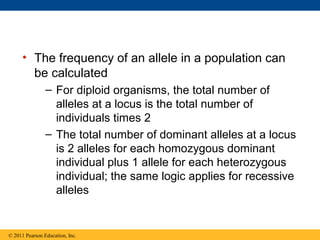

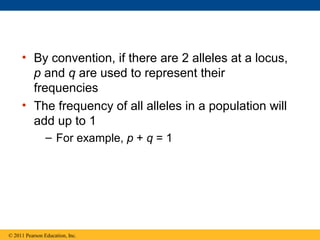

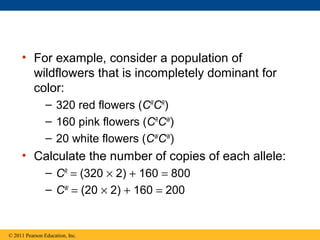

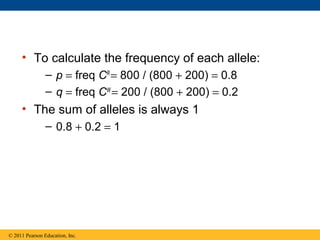

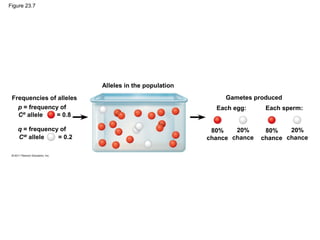

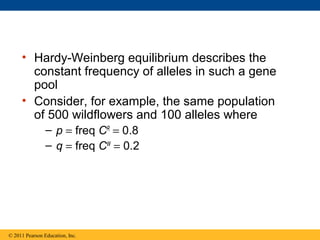

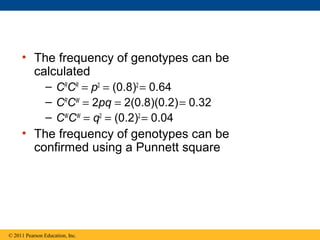

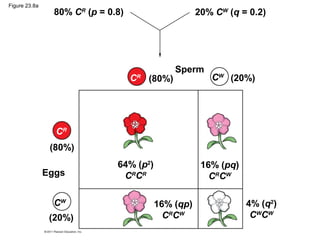

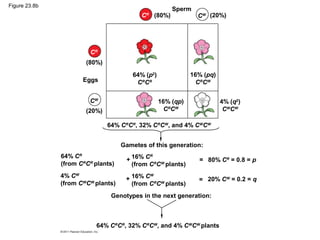

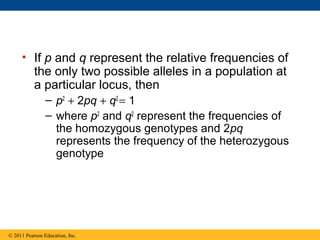

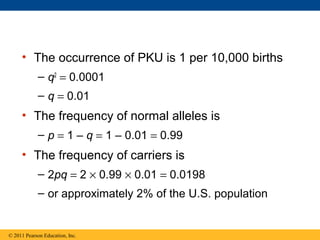

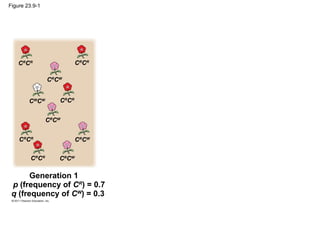

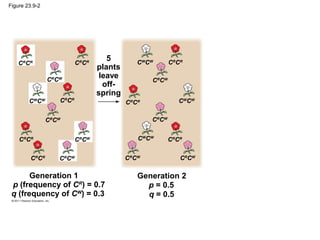

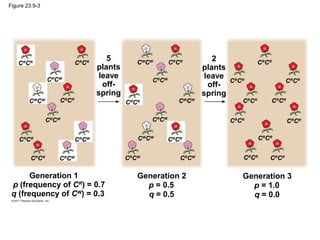

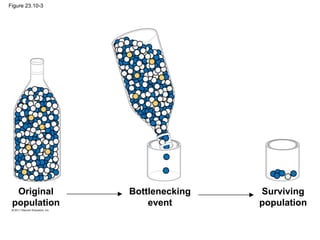

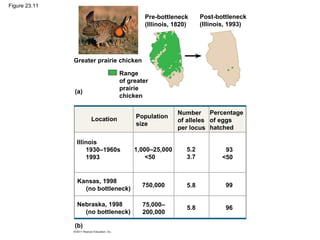

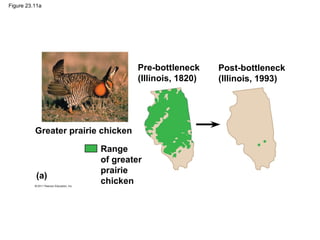

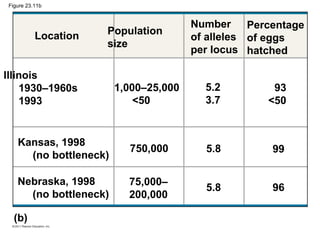

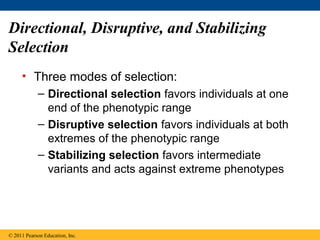

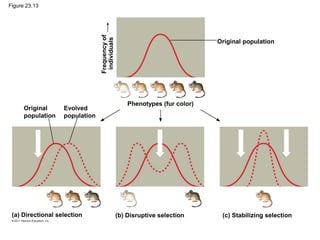

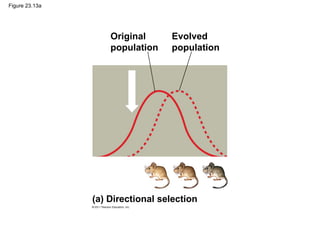

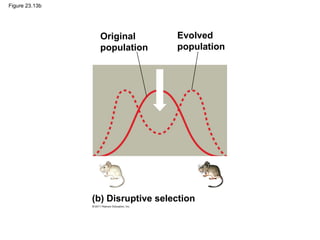

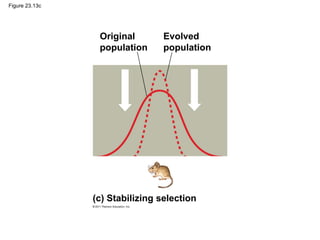

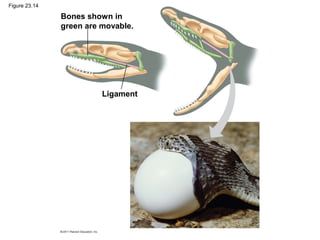

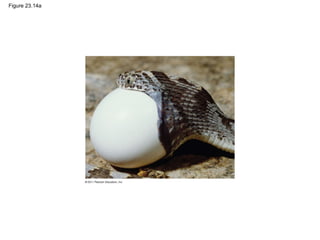

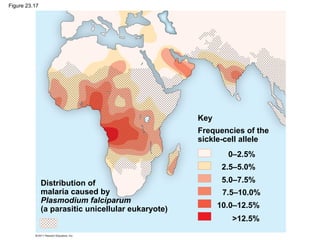

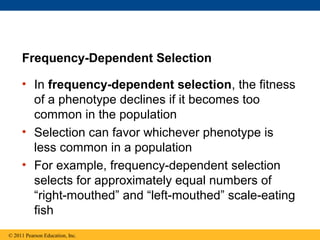

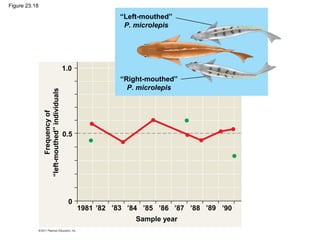

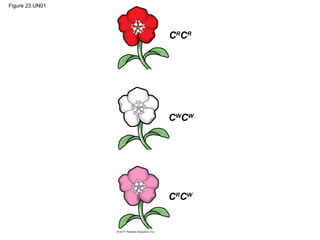

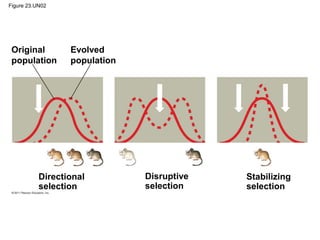

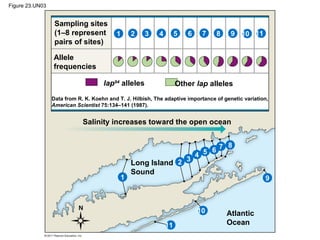

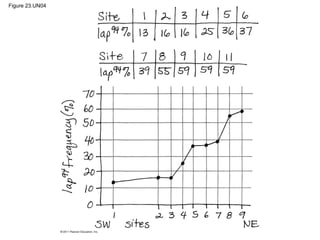

The document summarizes key concepts from Chapter 23 of Campbell Biology about the evolution of populations. It discusses how genetic variation within and between populations arises from mutations, genetic recombination during sexual reproduction, and other processes. The Hardy-Weinberg principle is introduced, stating that allele and genotype frequencies remain constant in a population not experiencing evolutionary influences like natural selection, genetic drift, or gene flow. Factors maintaining or disrupting Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium are also reviewed.