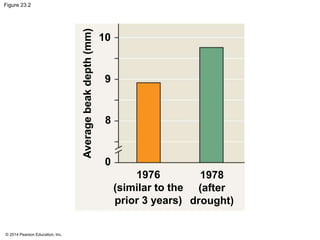

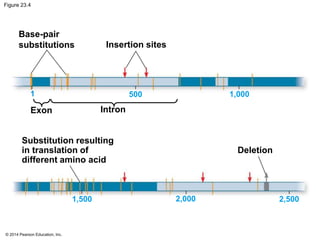

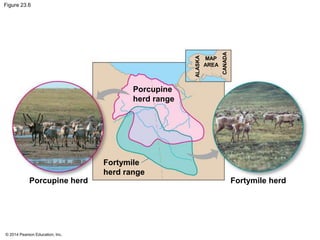

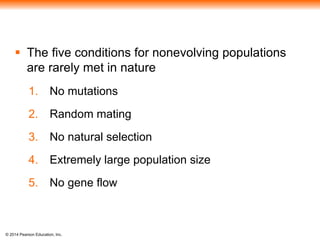

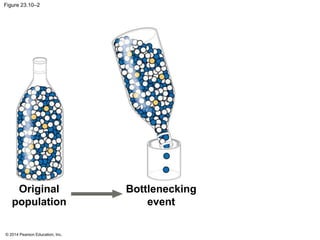

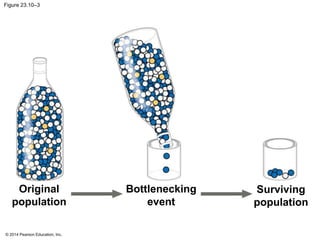

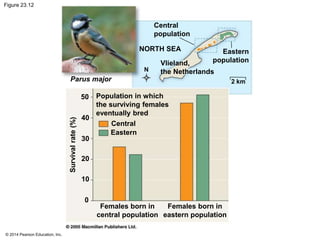

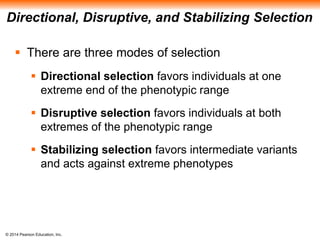

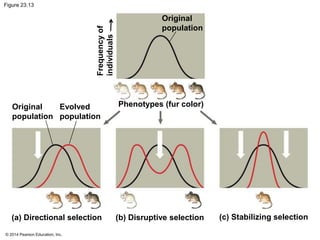

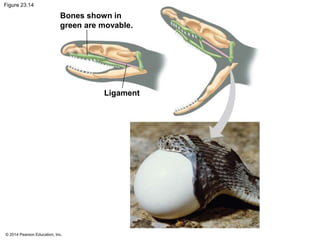

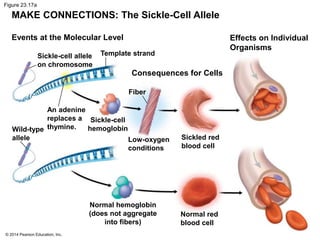

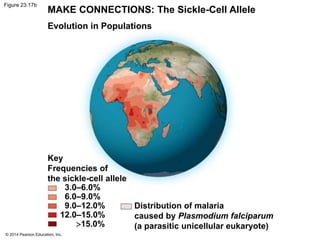

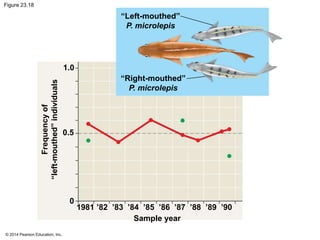

This document summarizes key concepts from Chapter 23 of Campbell Biology about the evolution of populations. It discusses how natural selection acts on populations by changing allele frequencies over generations, leading to microevolution. Populations evolve only if there is genetic variation, which arises from mutations and sexual reproduction. The Hardy-Weinberg principle describes how allele frequencies remain stable in populations not experiencing evolutionary forces like natural selection, genetic drift, or gene flow. Selection, drift, and other factors can cause populations to deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium over time.