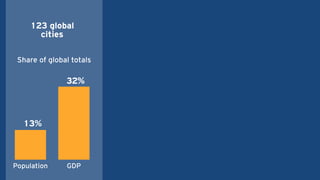

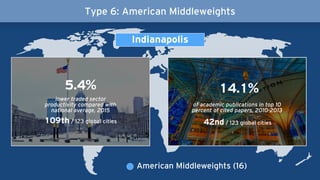

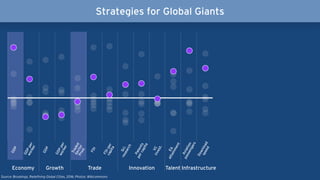

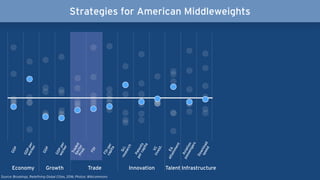

The document discusses global cities and their competitiveness. It identifies seven types of global cities based on their population, GDP, talent, traded sectors, innovation, infrastructure, industry characteristics, and economic characteristics. The first type discussed are "Global Giants," which are the largest global cities by population and GDP that play a dominant role in the global economy.

![“The problem [is] not globalization, but how

the process [is] being managed.”

- Joseph Stiglitz

Source: “Globalization and its New Discontents,” Project Syndicate, August 2016](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2016-09-29gcisummitv10-161003141838/85/2016-09-29-gci-summit-v10-53-320.jpg)