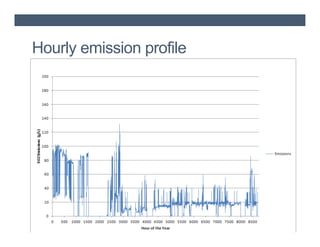

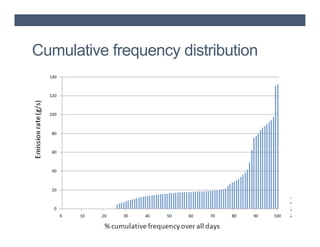

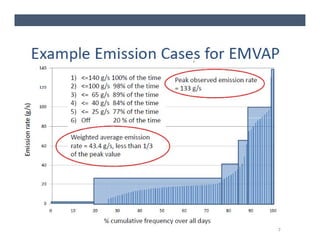

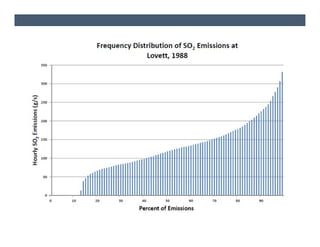

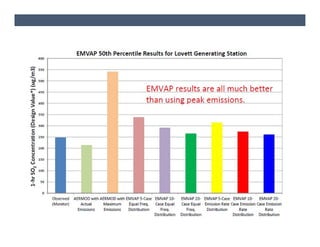

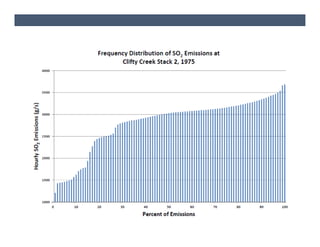

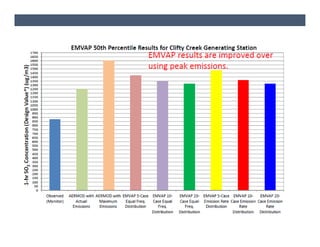

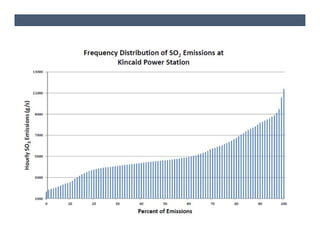

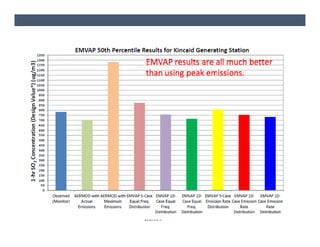

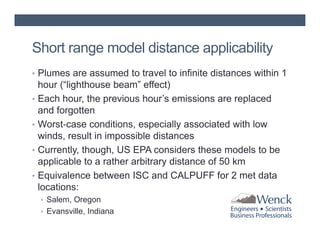

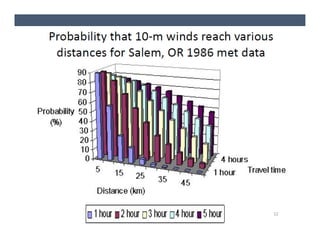

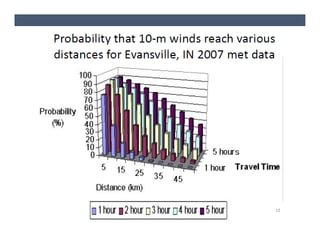

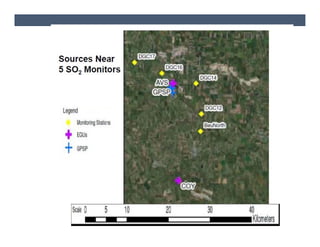

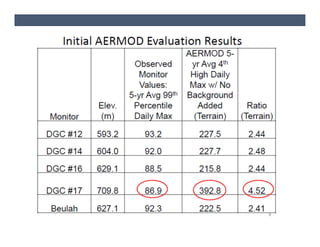

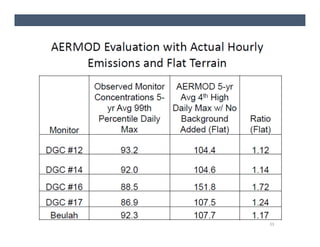

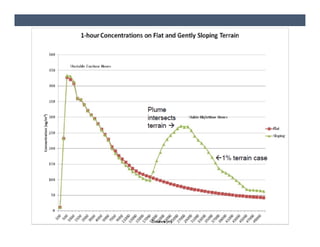

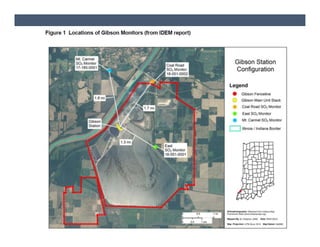

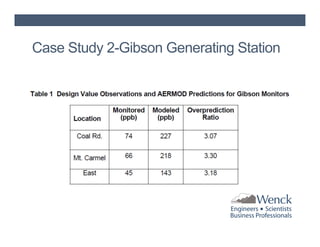

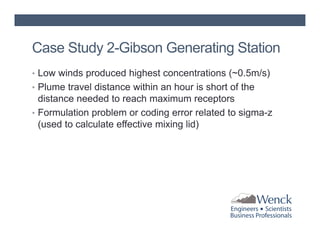

The document presents air dispersion modeling highlights shared during the 2012 A&WMA UMS Board Meeting, focusing on the use of models like AERMOD for predicting air quality and its limitations. It discusses various case studies, including air quality assessments in North Dakota and the Gibson generating station, emphasizing modeling challenges and the importance of accurate emission variability processing. The findings indicate significant variability in modeled results based on emission rates and the appropriateness of distance limitations in dispersion models.