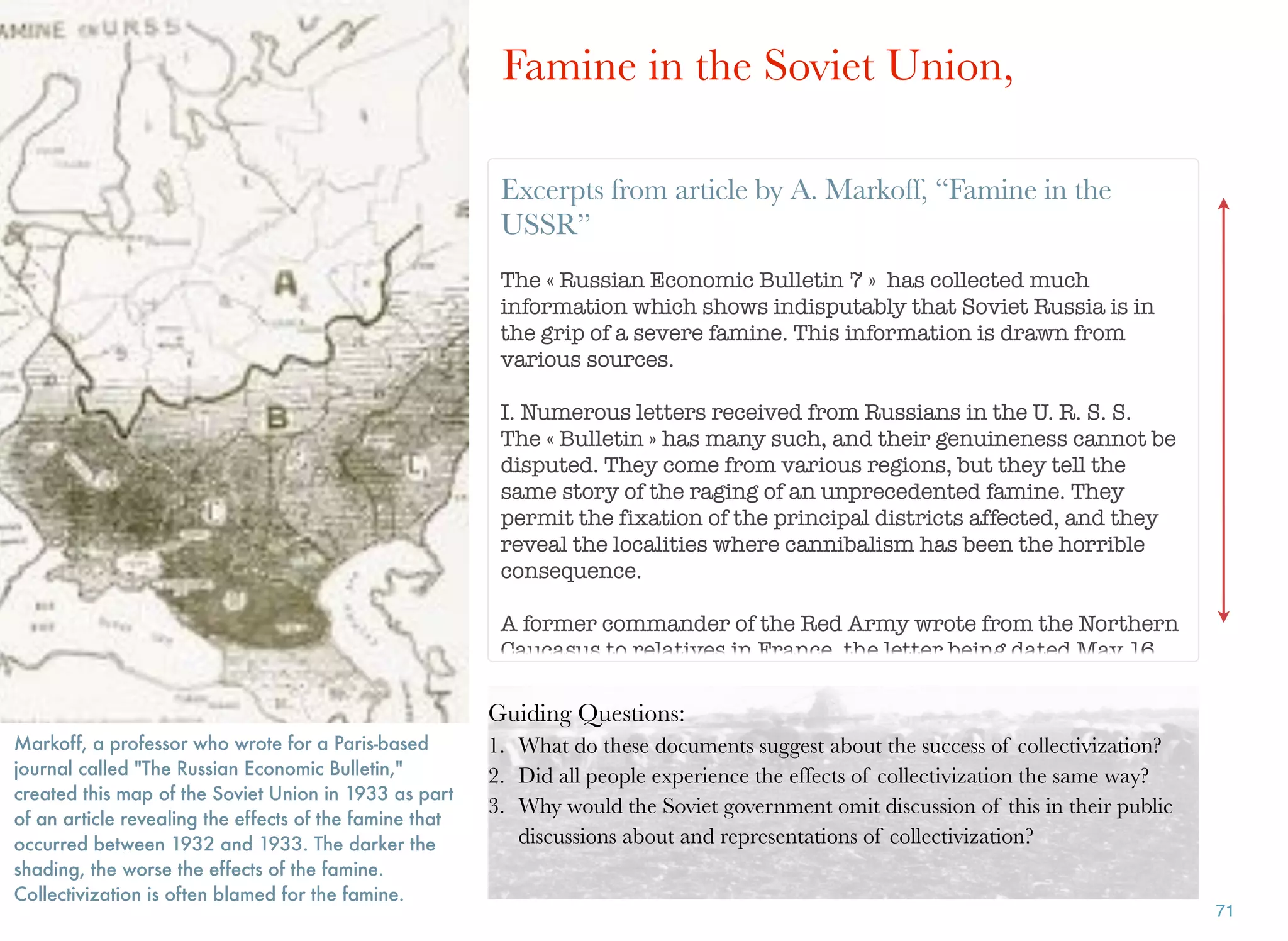

The document explores the effects of collectivization in Stalin's Soviet Union, highlighting the shift from traditional peasant agriculture to government-controlled collective farms starting in 1929. It presents two perspectives: the Soviet government's view, which saw collectivization as a path to equality and economic success, and the peasants' reactions, which ranged from confusion and resistance to seeing it as an opportunity for education. The document concludes by prompting historians to analyze the true impacts of collectivization on individuals and society and the relationship between government narratives and lived realities.

![Peter Pappas, editor

School of Education ~ University of Portland

His popular blog, Copy/Paste features downloads of his instructional

resources, projects and publications. Follow him at Twitter @edteck.

His other multi-touch eBooks are available at here.

© Peter Pappas and his students, 2016

The authors take copyright infringement seriously. If any copyright holder has

been inadvertently or unintentionally overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to

remove the said material from this book at the very first opportunity.

ii

Cover design by Anna Harrington

Cover image: Timeless Books

By Lin Kristensen from New Jersey, USA

[CC BY 2.]

via Wikimedia Commons](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/collectivizationandpropagandainstalinssovietunion-170117215726/75/Collectivization-and-Propaganda-in-Stalin-s-Soviet-Union-19-2048.jpg)