This document discusses the concepts of validity, soundness, inductive and deductive arguments. It provides examples of valid and invalid arguments. The key points are:

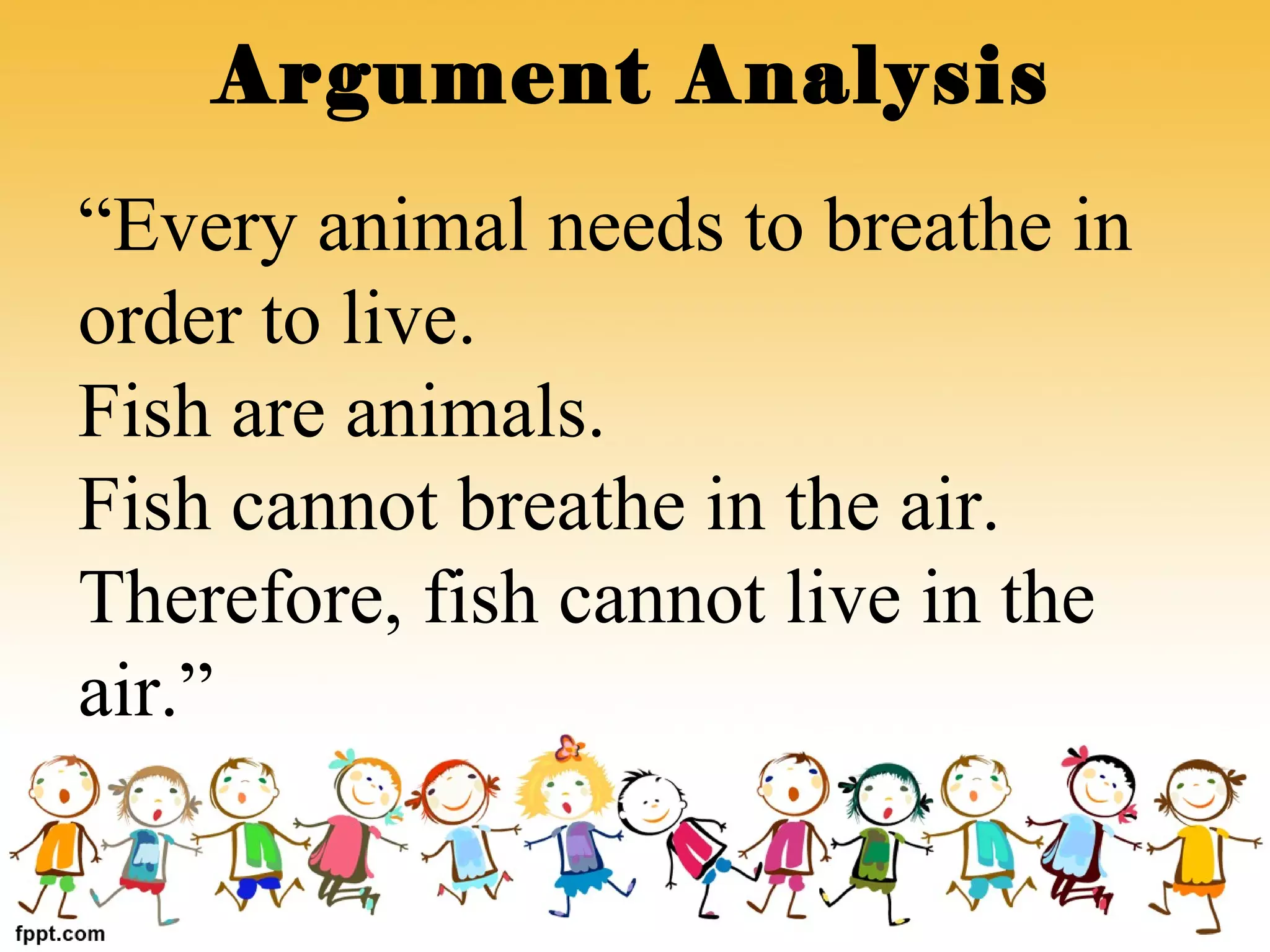

- Inductive arguments cite evidence to reasonably support a conclusion, while deductive arguments aim to conclusively establish a thesis.

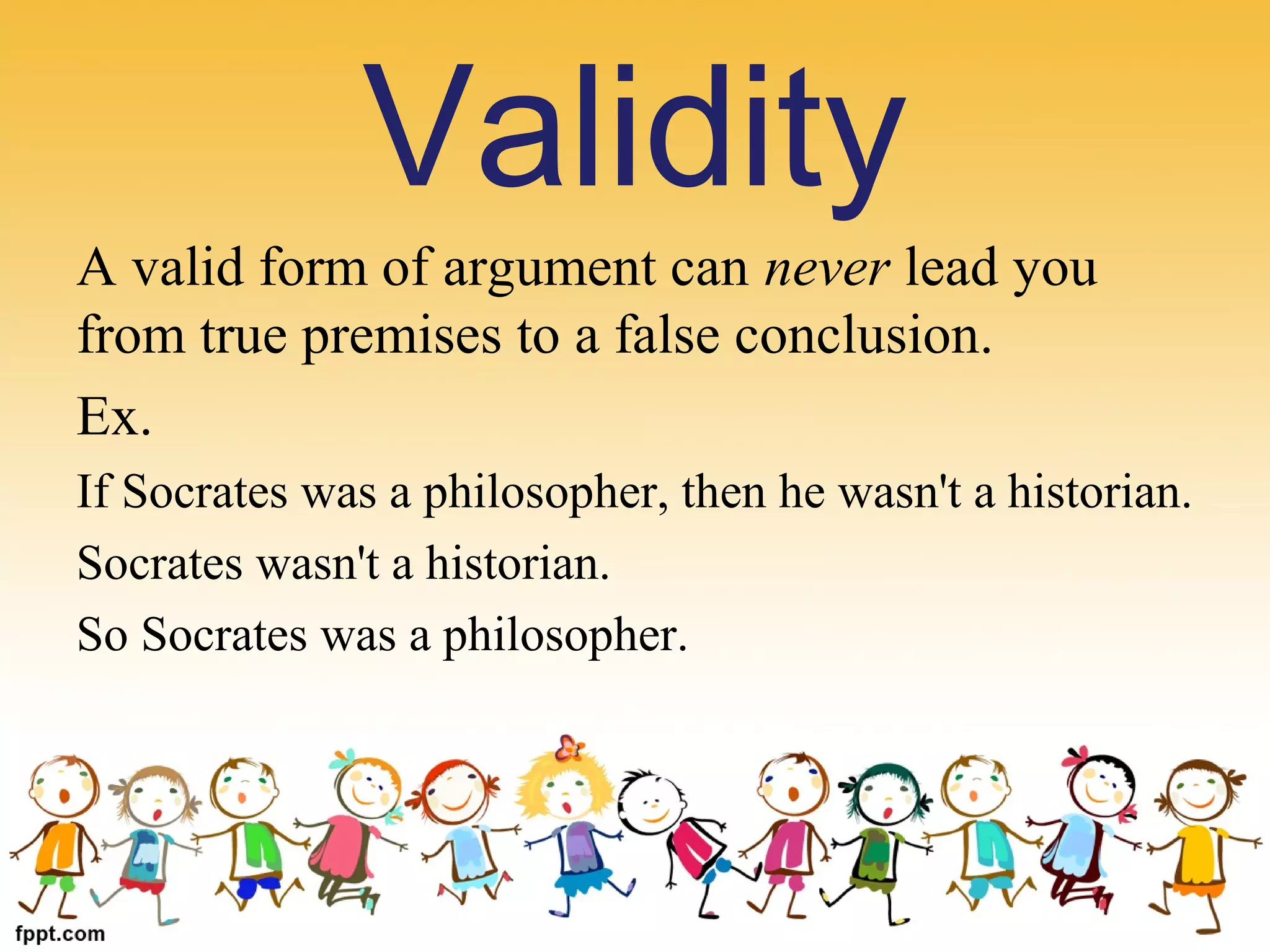

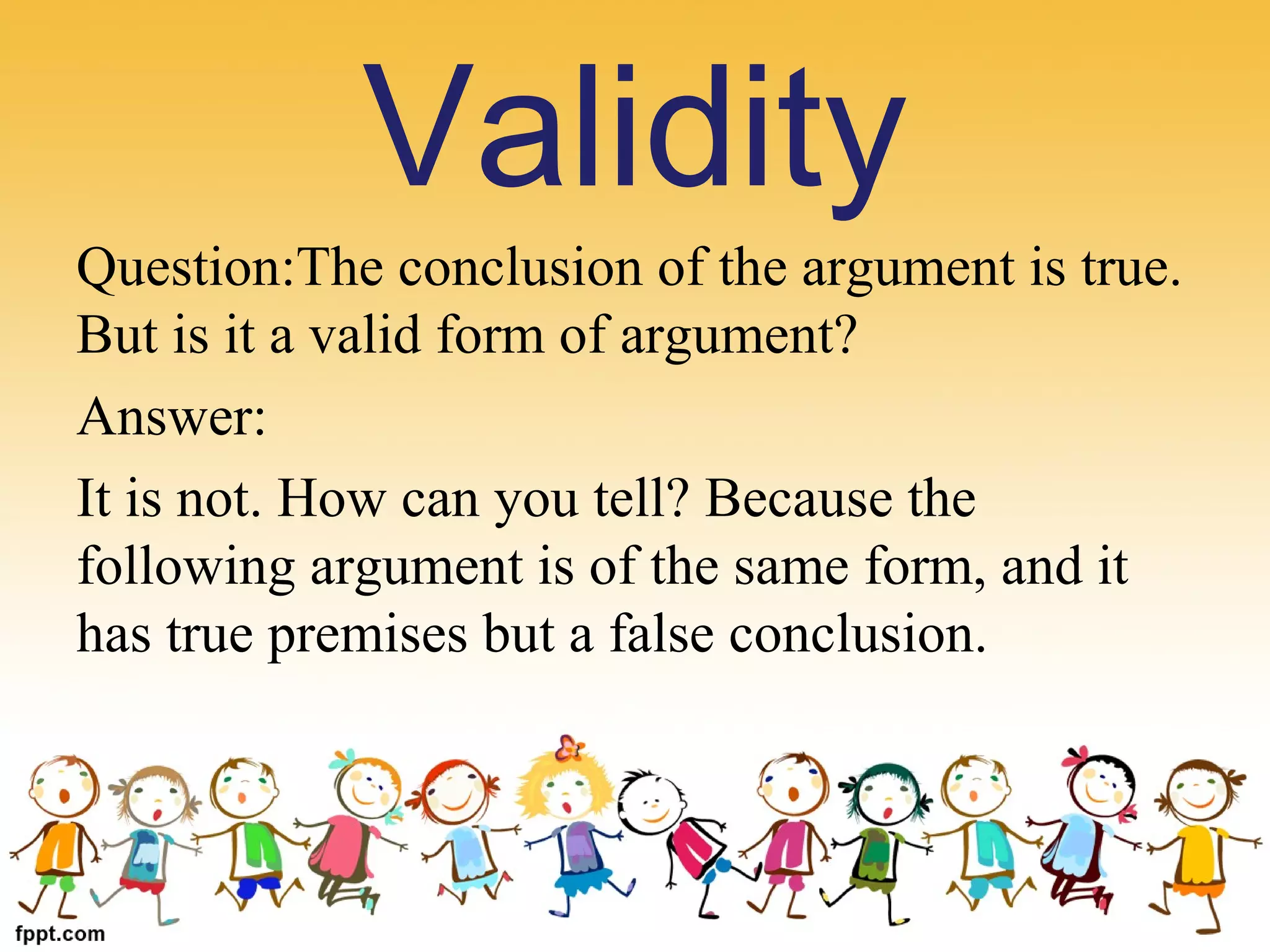

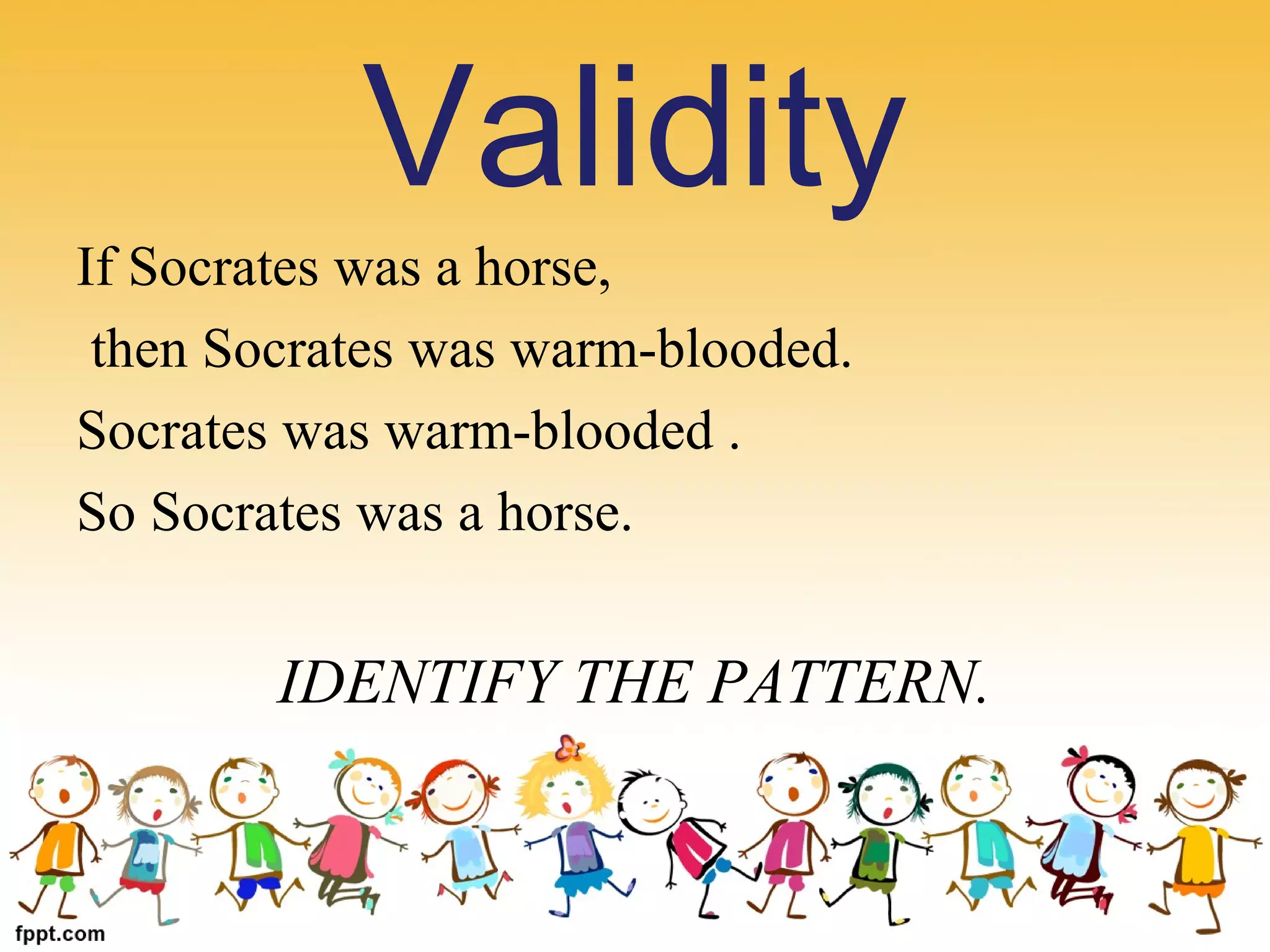

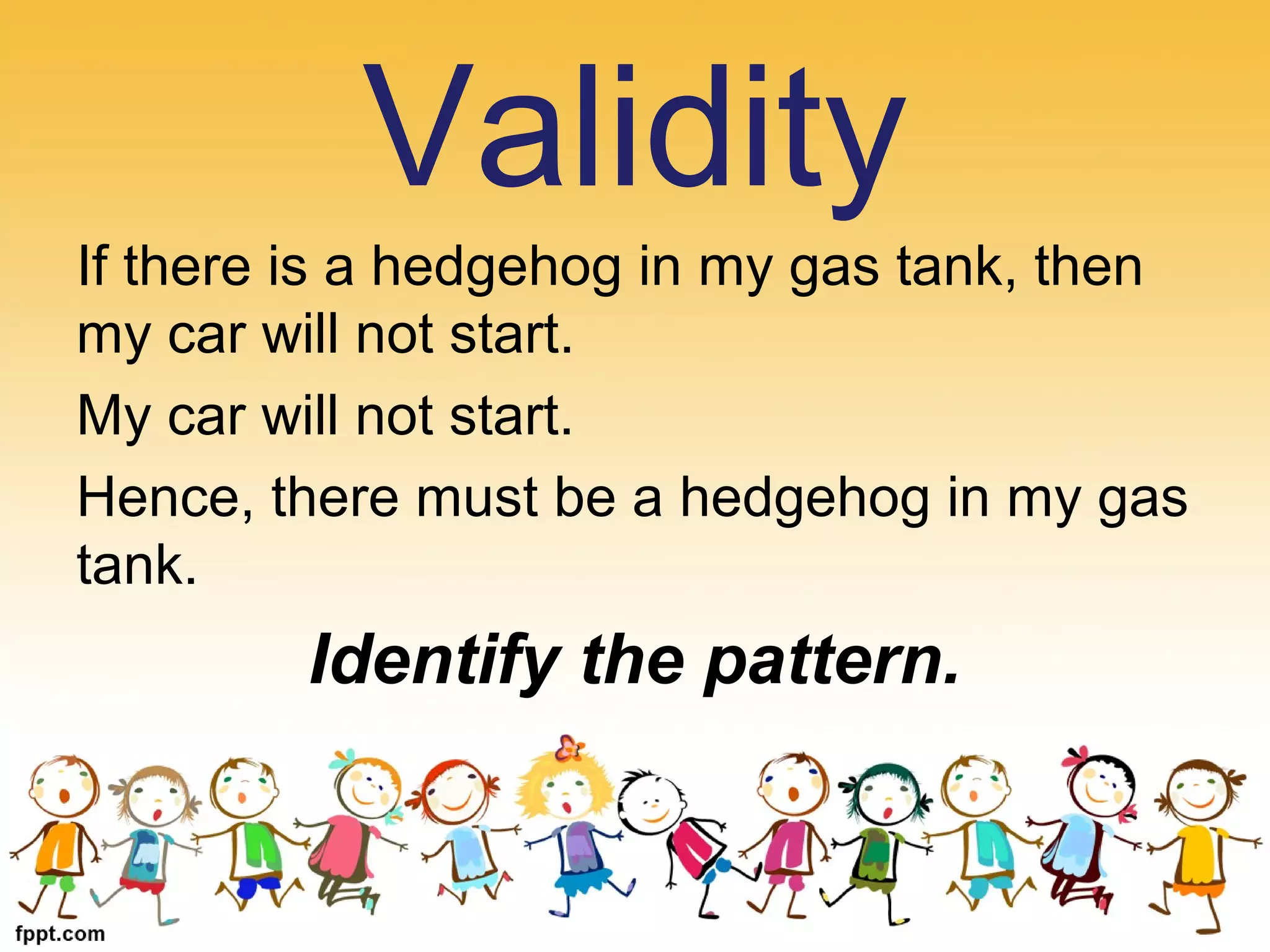

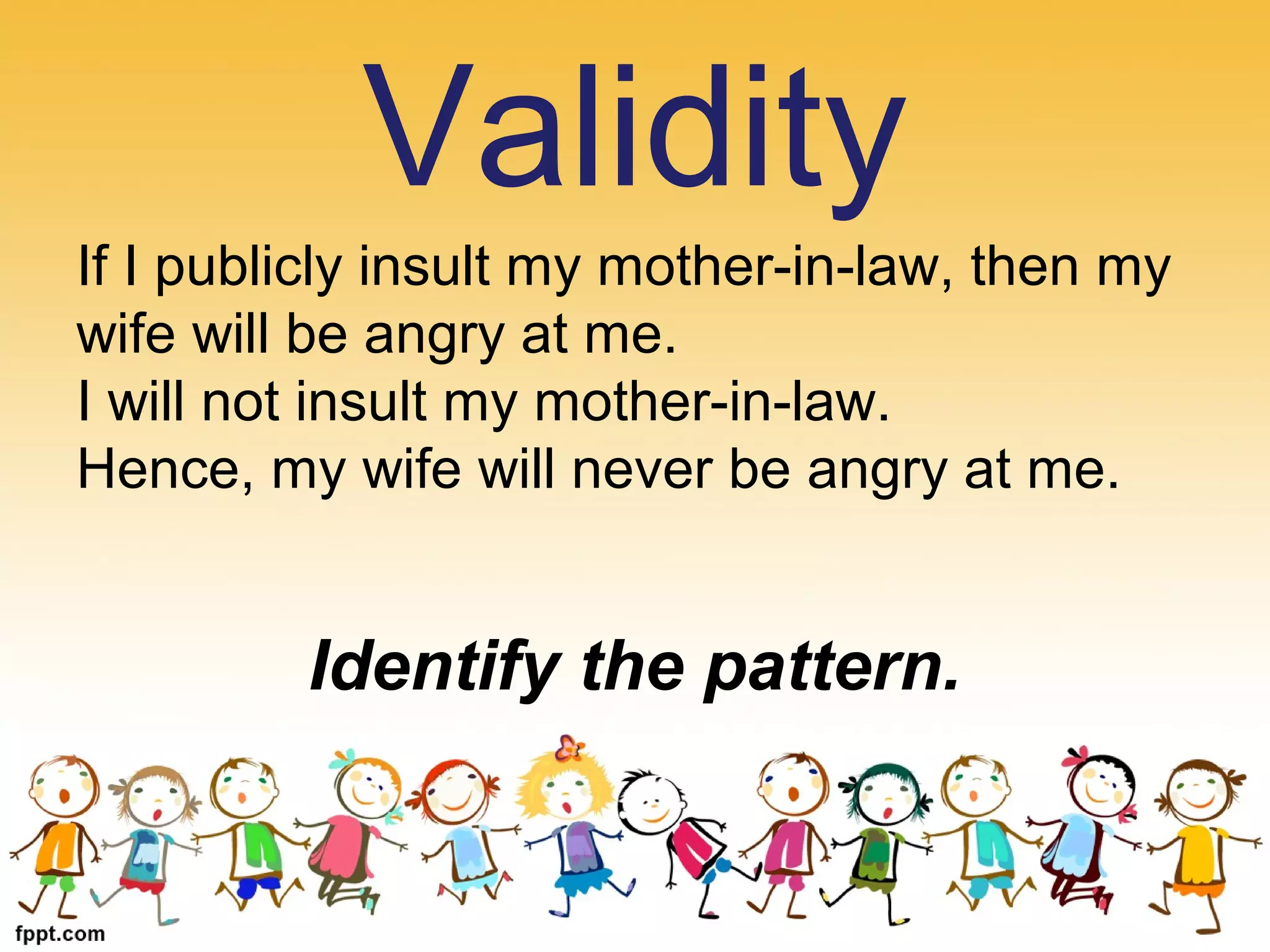

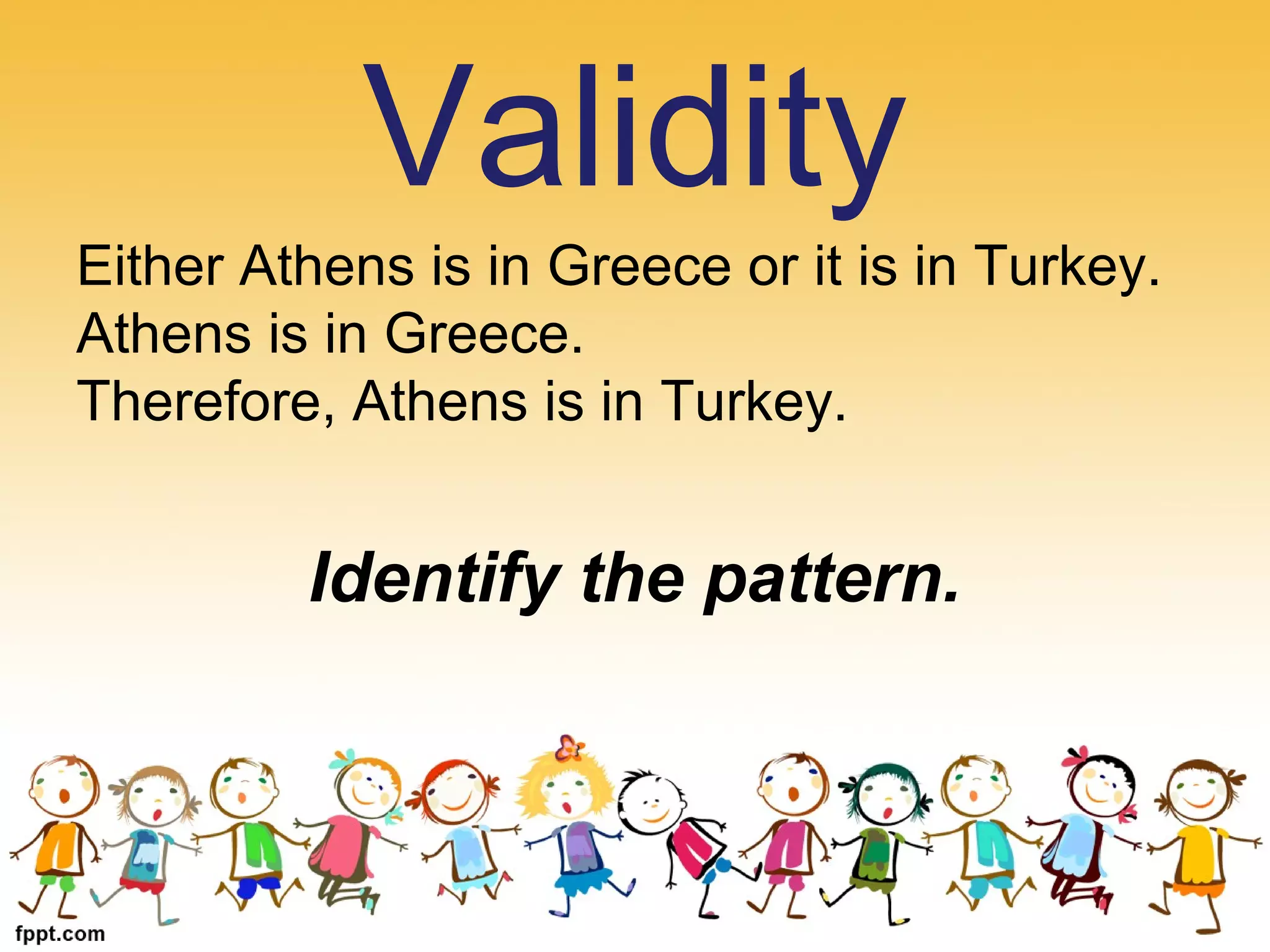

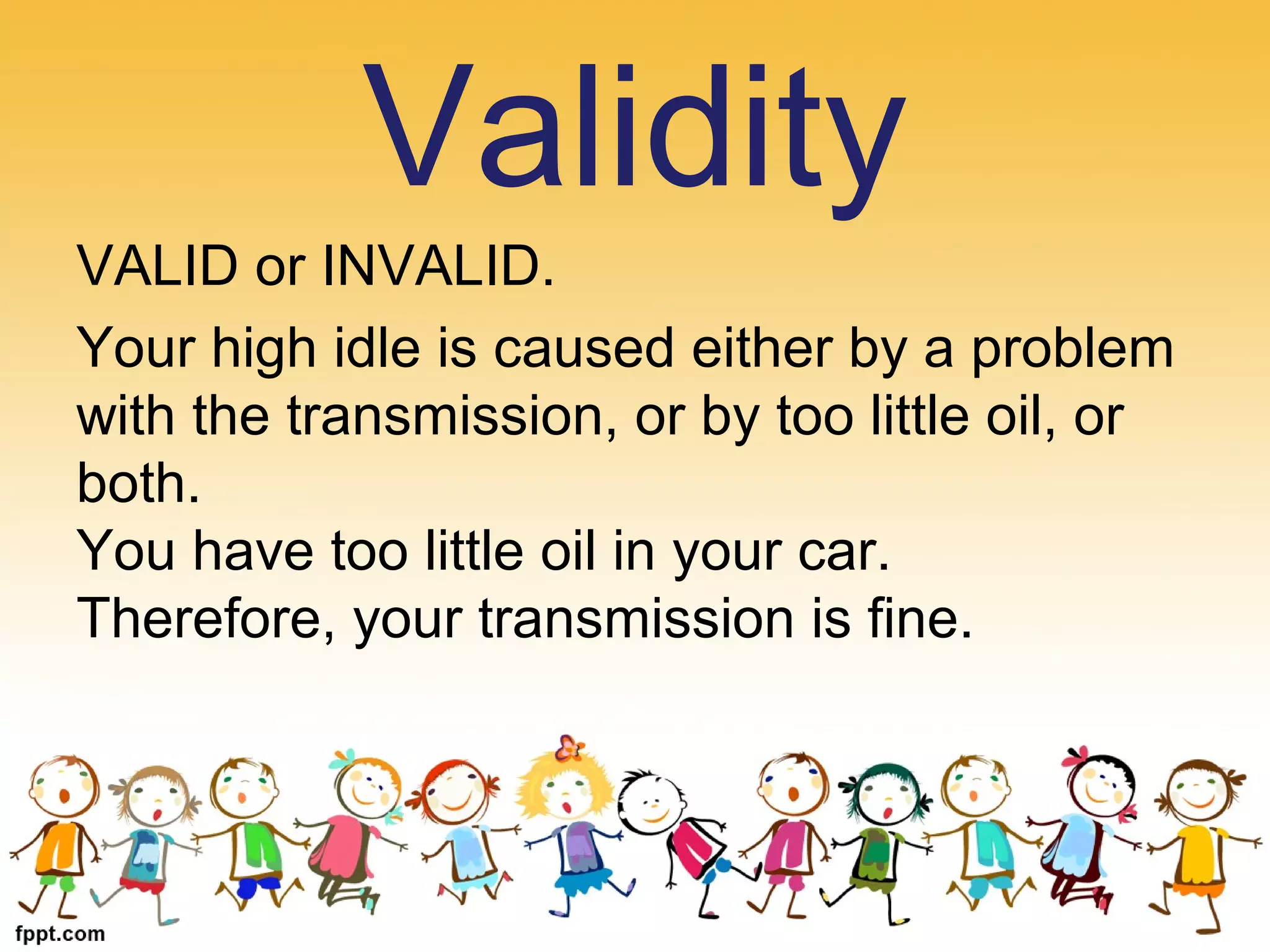

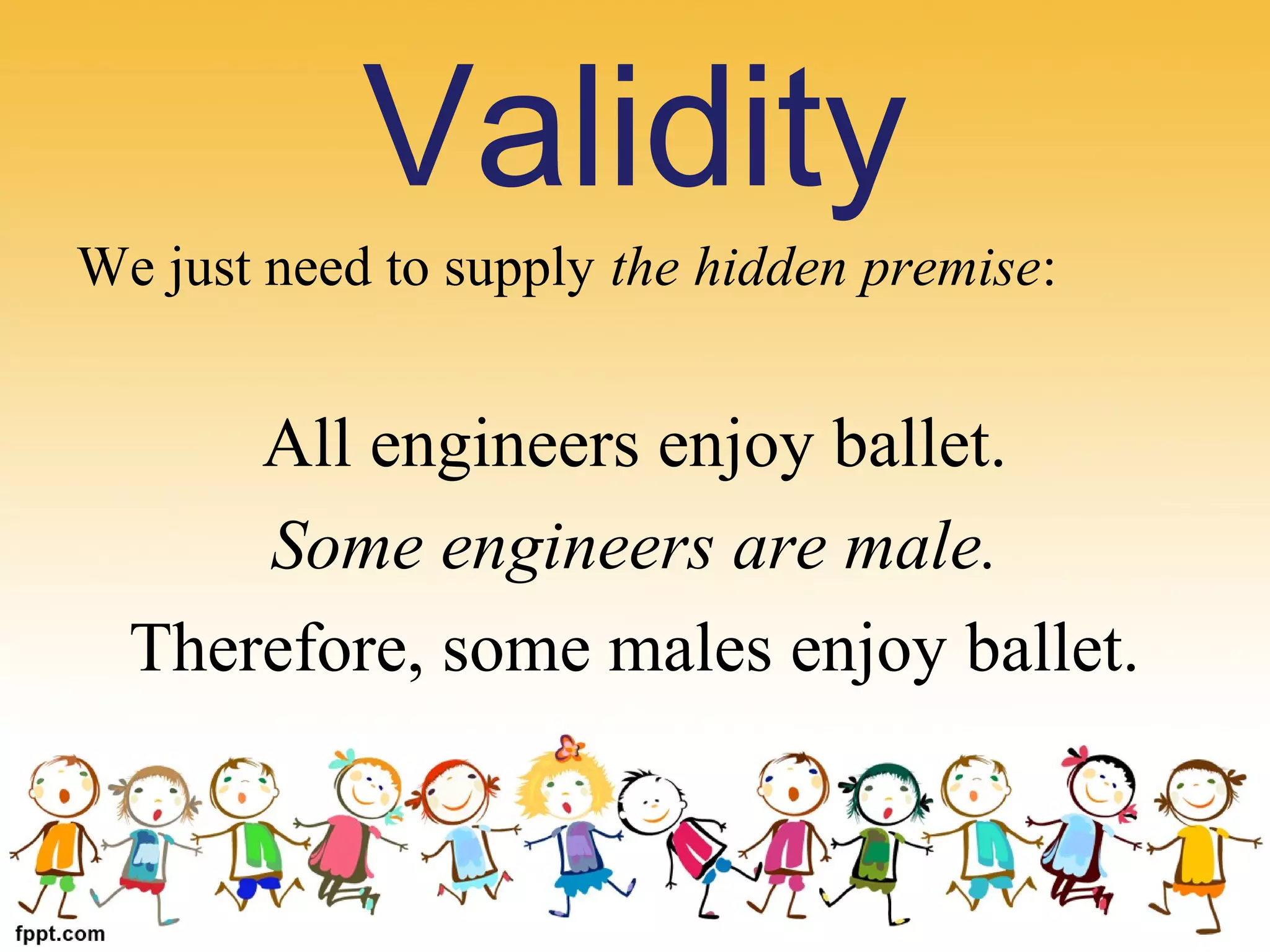

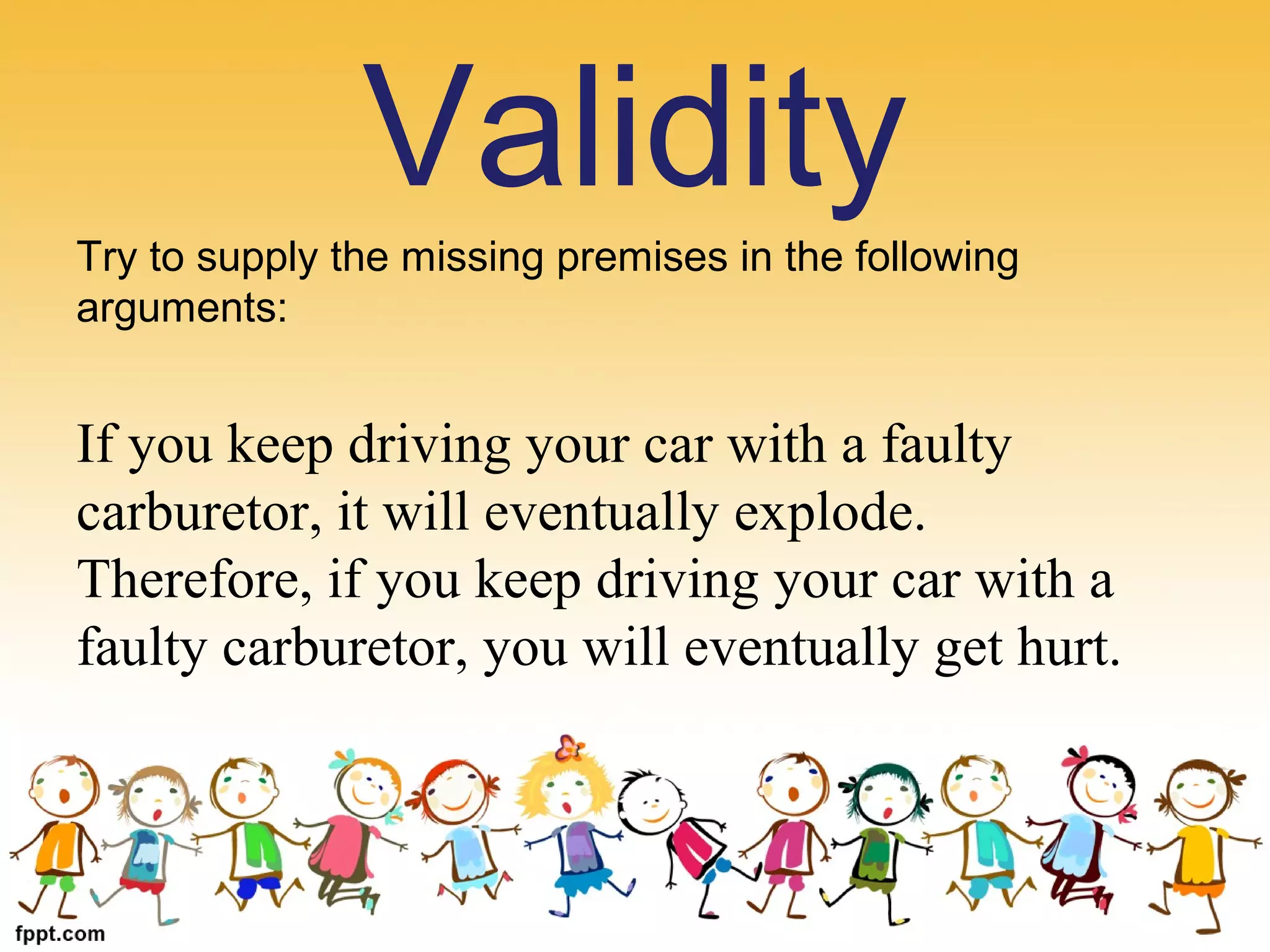

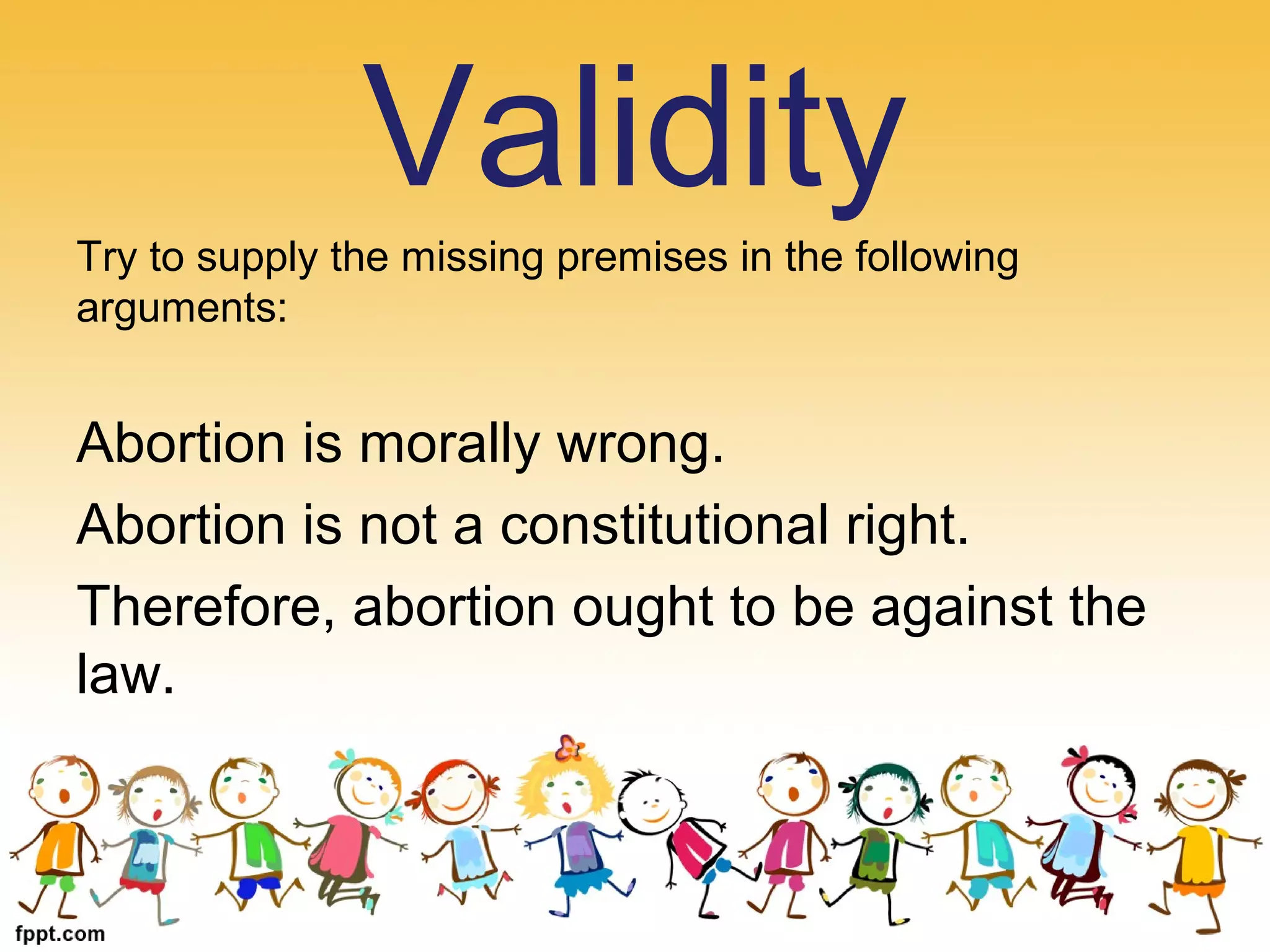

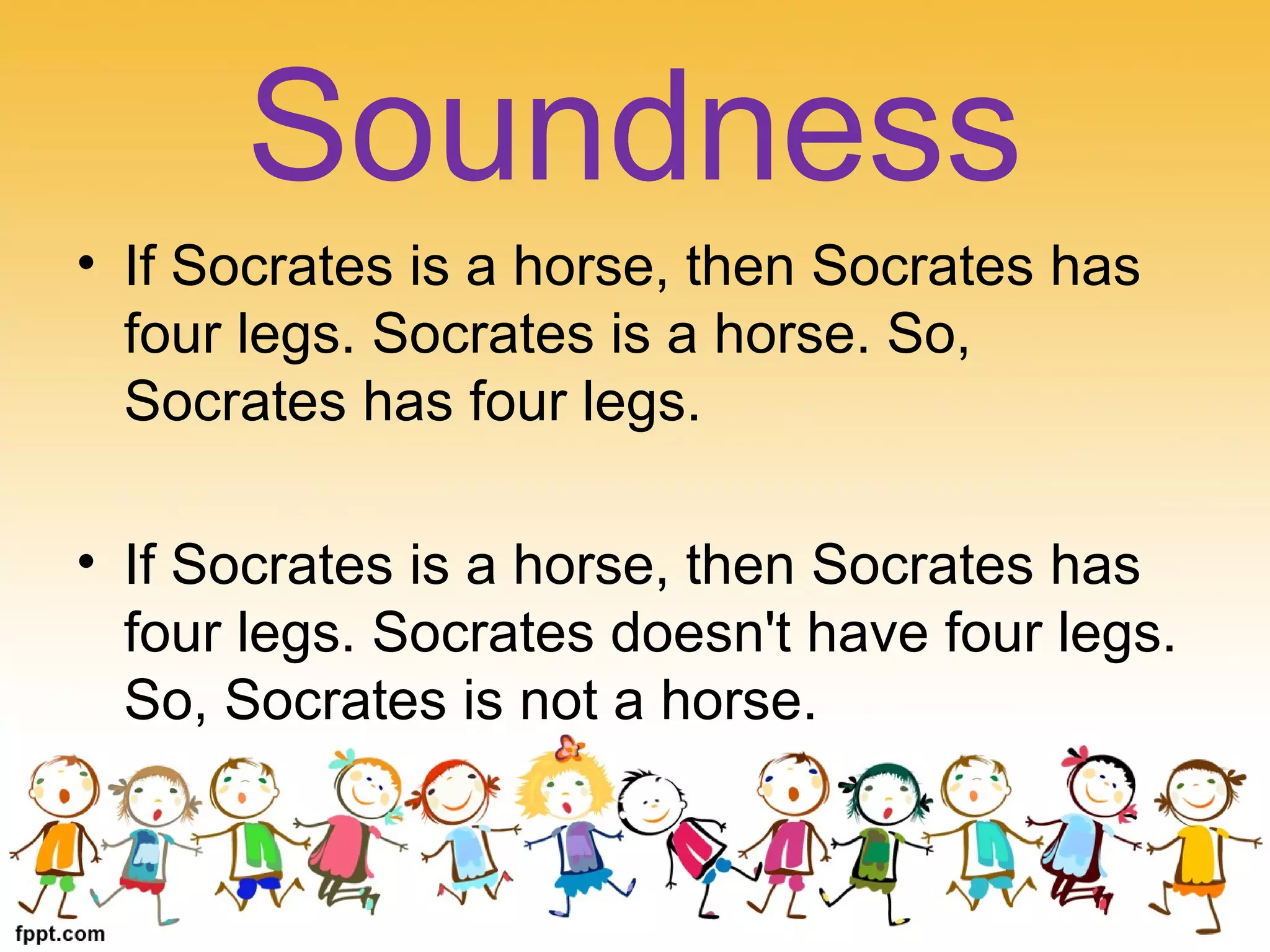

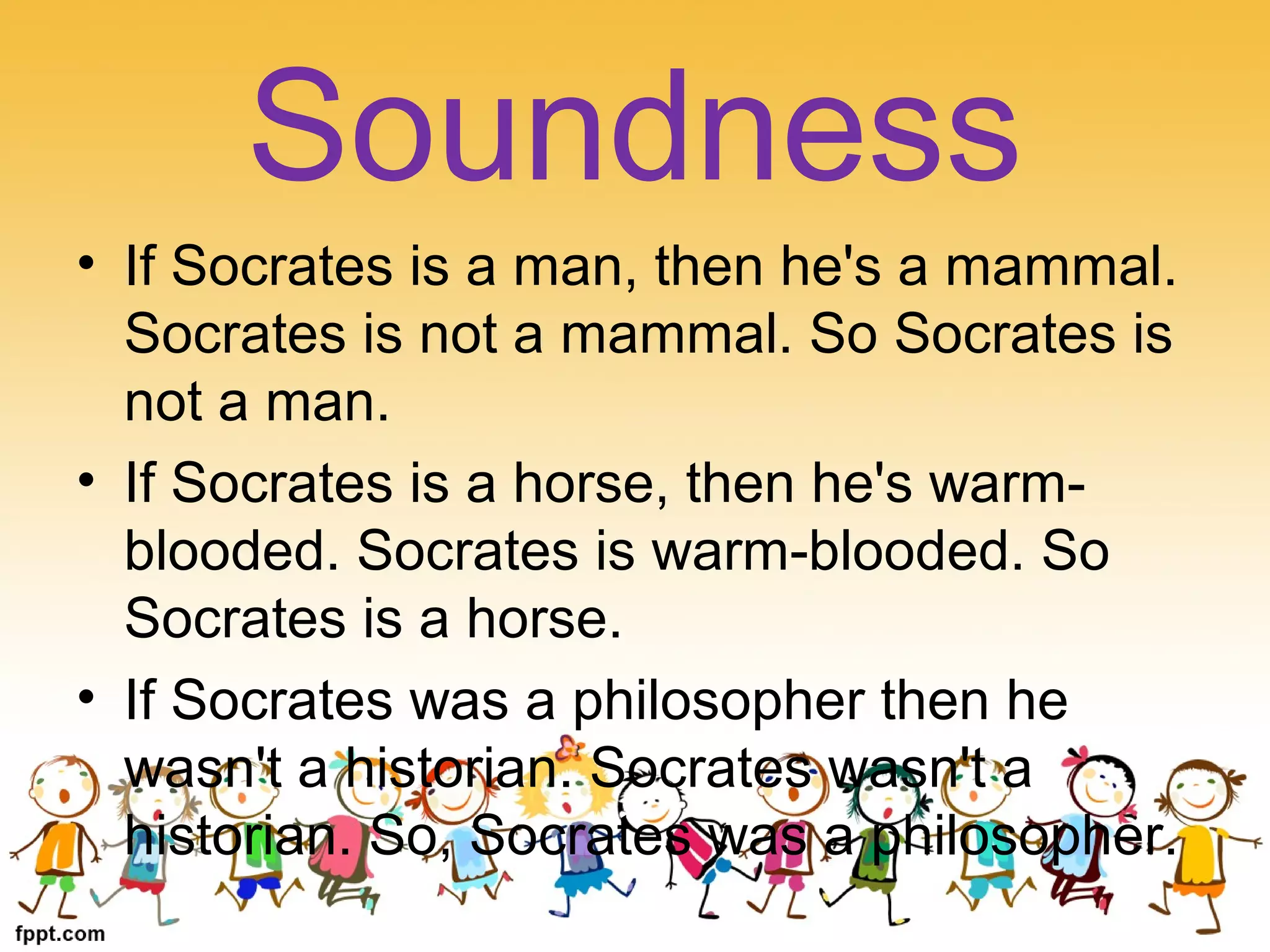

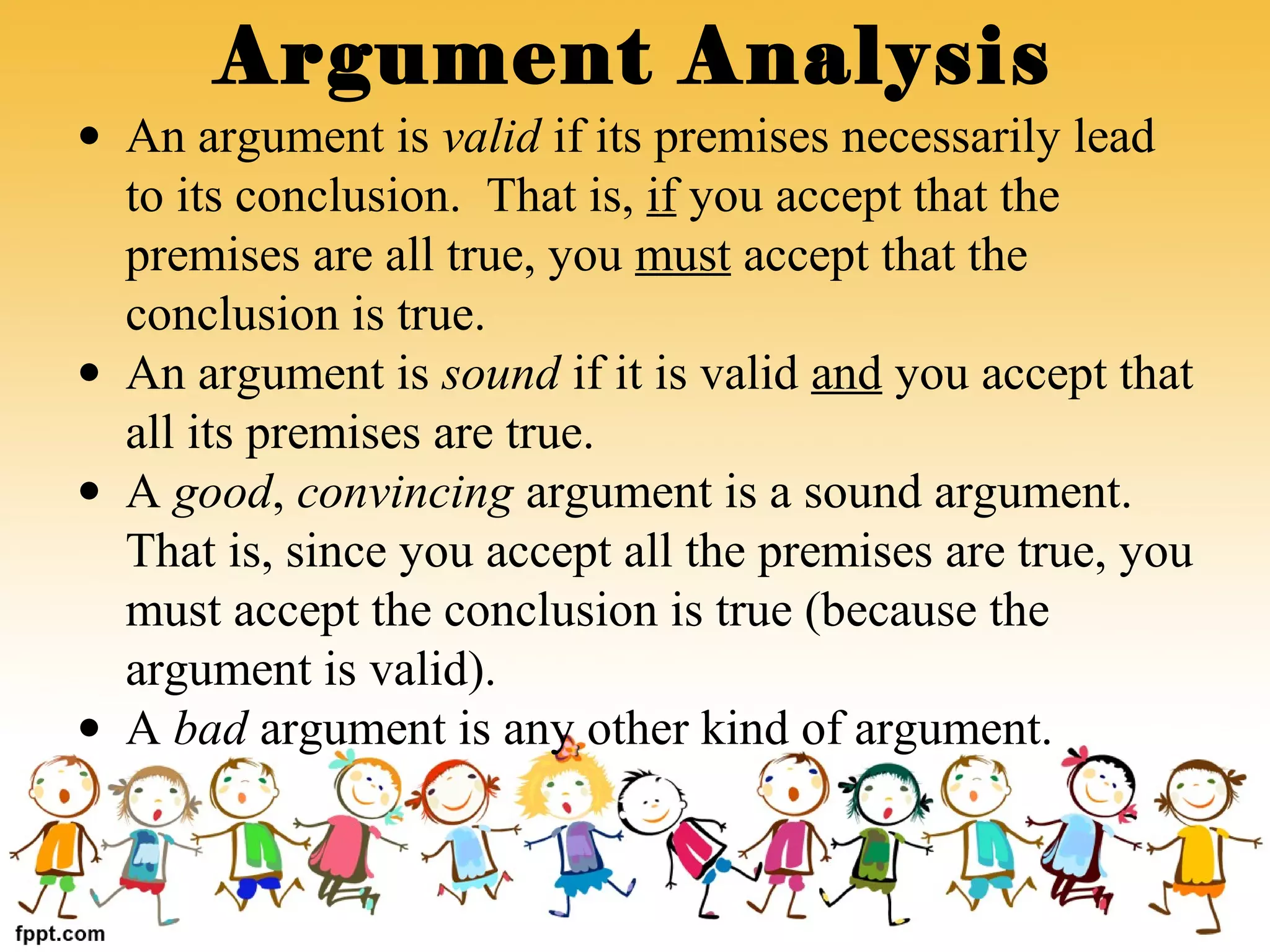

- An argument is valid if the conclusion must be true if the premises are true, regardless of whether the premises and conclusion are actually true.

- An argument is sound if it is valid and all premises are true, making the conclusion necessarily true.

- Examples are used to illustrate valid versus invalid argument forms and how to identify the patterns that determine validity.

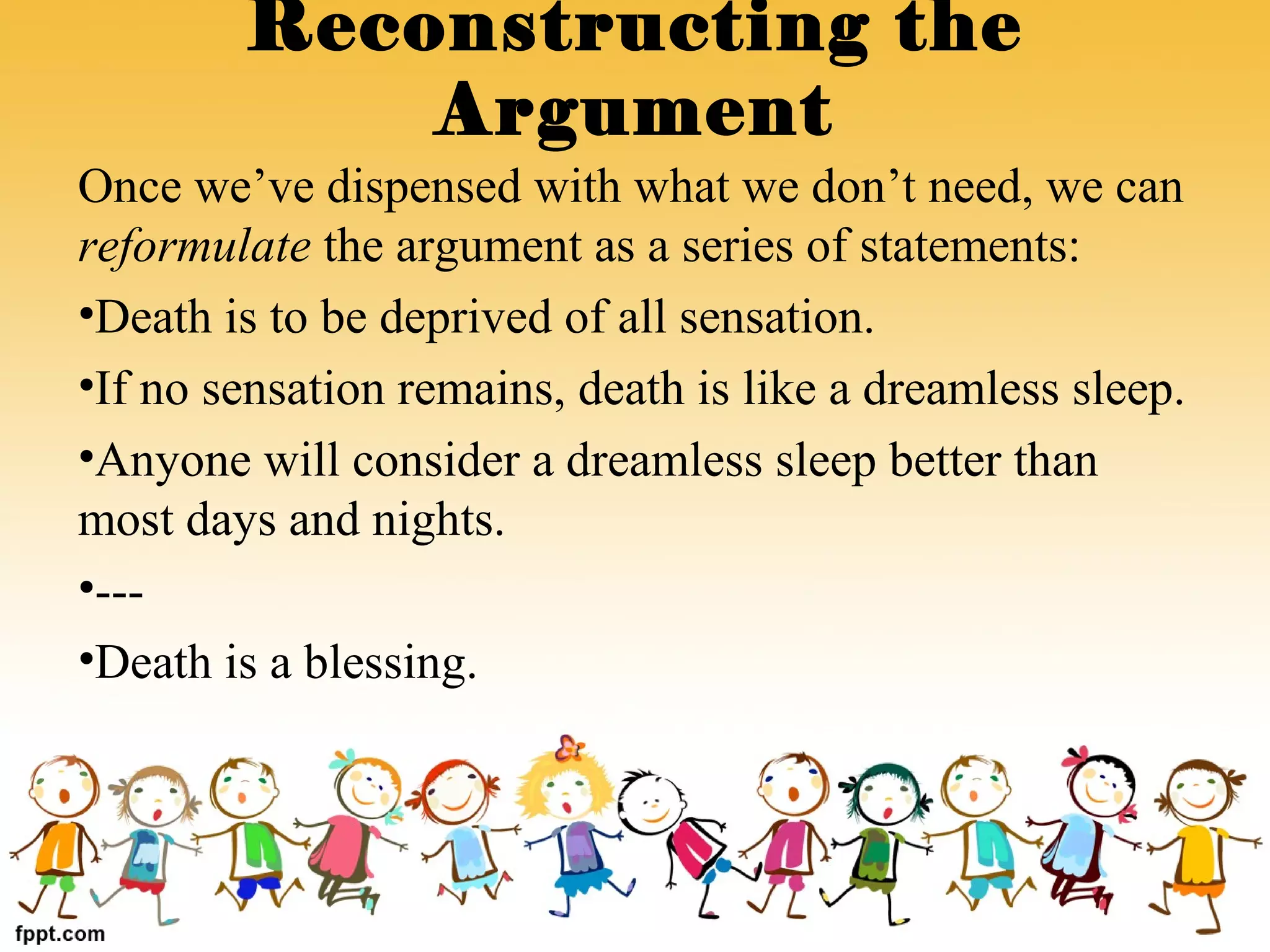

![To proceed, we first have to get rid of anything unnecessary –

mere rhetorical flourishes, repetitions, and irrelevancies. Go

through the passage and get rid of anything that doesn’t support

the conclusion in some way:

•“For Death is to be deprived of all sensation... if no sensation

remains, then death is like a dreamless sleep. ...death will be a

blessing. ...if any one compares such a night [of sleep without

dreams]... with the other nights and days of his life, and should

declare how many he had passed better and more pleasantly than

this night, I think.. [he] would find so small a number...”

Reconstructing the

Argument](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/validandsoundargument-150811133244-lva1-app6892/75/Valid-and-sound-Argument-disclaimer-40-2048.jpg)