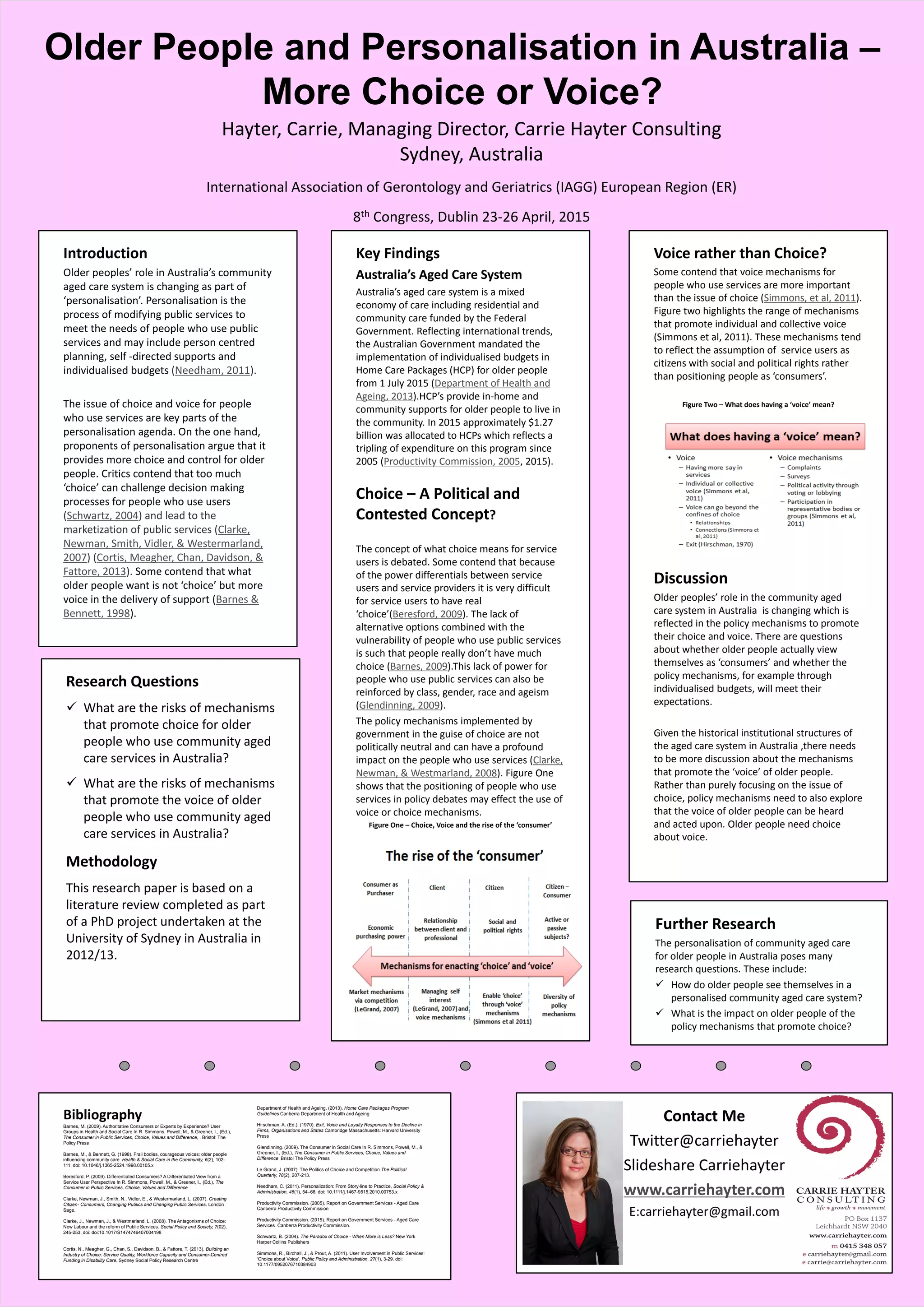

This document discusses the changing role of older people in Australia's aged care system, which is moving towards a model of "personalization." While proponents argue this provides more choice and control, critics contend that too much choice can overwhelm users and lead to marketization of services. The research questions examine the risks of mechanisms promoting choice and voice for older community care users. There is debate around what choice truly means for vulnerable users and whether voice mechanisms are more important than choice. The discussion suggests Australia needs more discussion on how to promote the voices of older users in policy design.