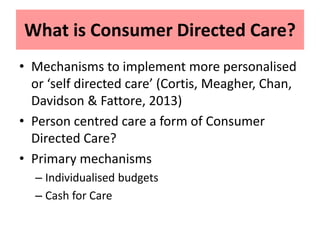

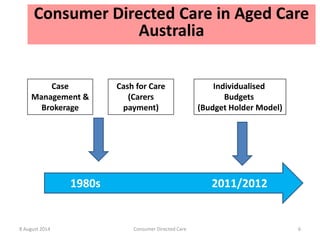

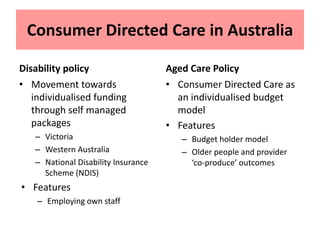

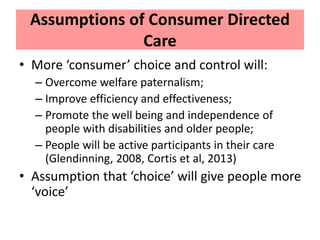

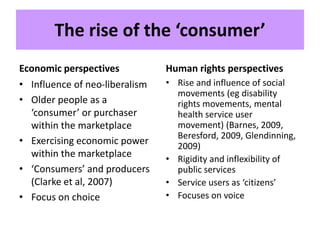

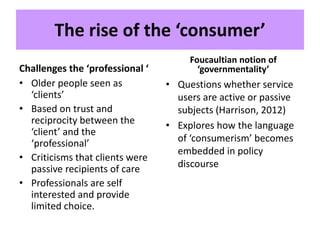

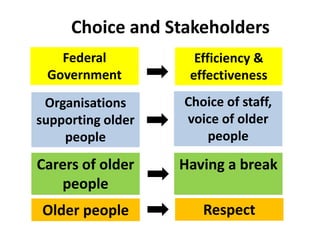

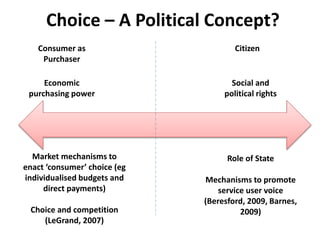

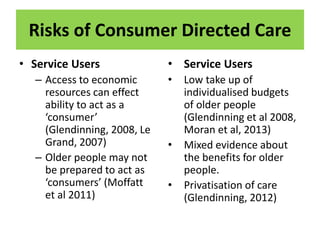

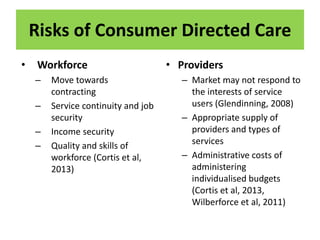

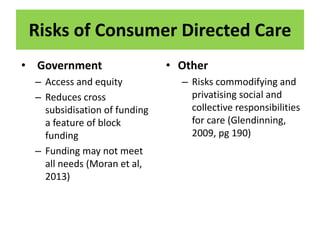

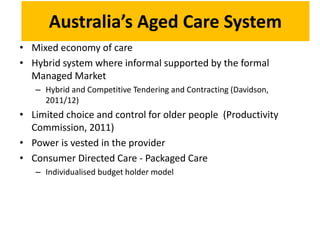

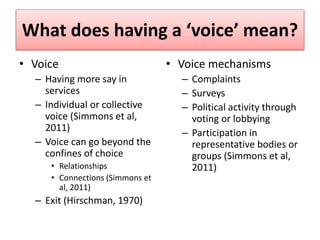

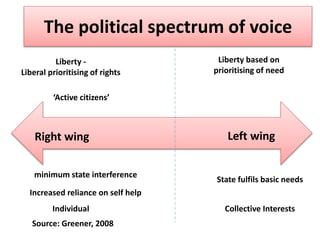

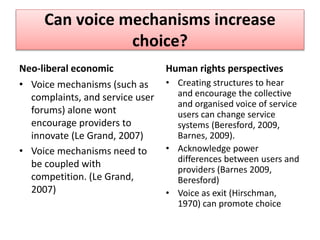

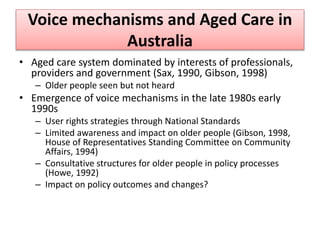

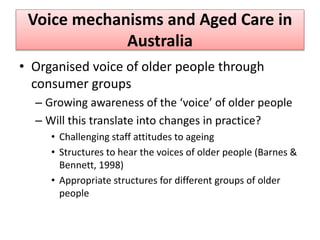

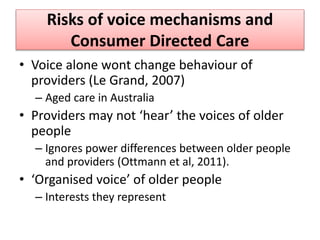

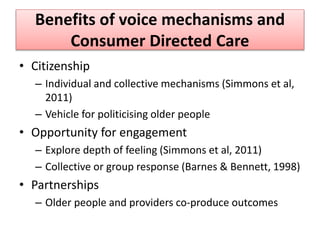

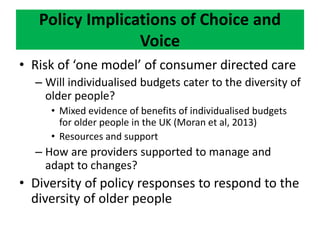

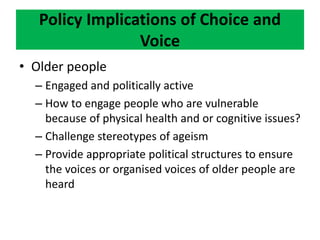

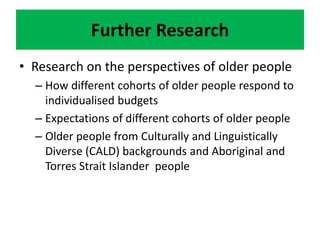

This document summarizes a presentation on consumer directed care and whether it provides more choice or voice for older people. It discusses the assumptions and benefits of consumer directed care, such as choice and control, but also notes risks like assumptions about choice and mechanisms for voice. It examines what choice and voice mean for different stakeholders and whether voice mechanisms can increase choice. The document concludes that choice alone is not enough and voice is important to have a say in services. It identifies implications for policy, research, and practice around supporting diversity in models of care and ensuring the voices of older people are heard.