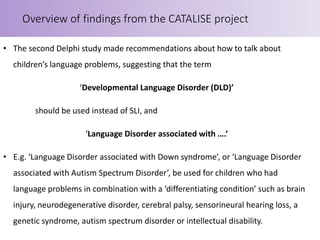

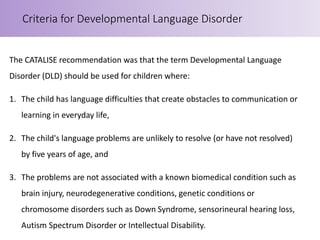

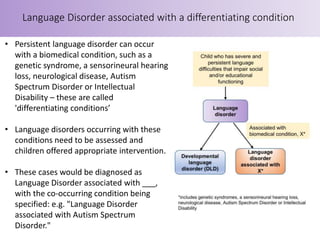

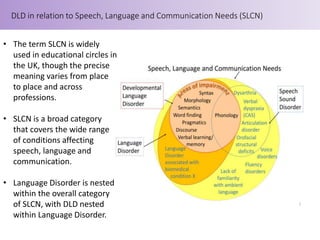

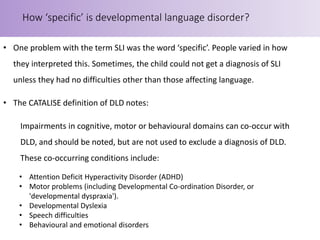

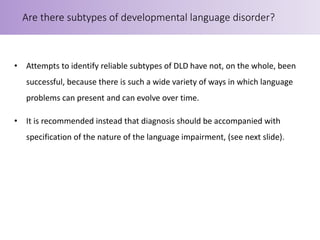

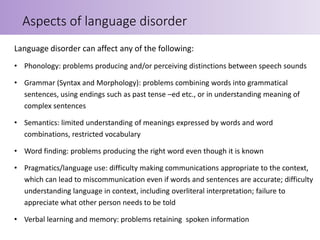

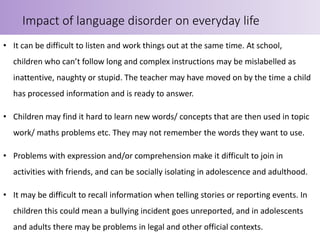

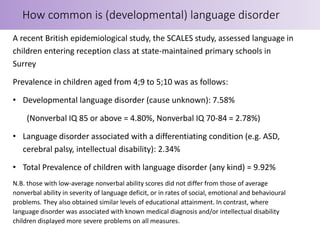

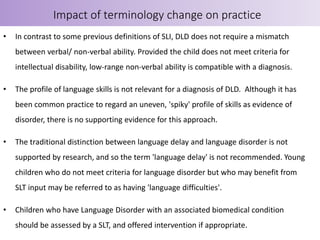

The document summarizes the findings and recommendations of the CATALISE project, which aimed to achieve consensus on terminology and criteria for developmental language disorders (DLD) in children. The project recommended replacing the term "specific language impairment" with DLD. DLD is defined as a persistent language disorder that affects everyday functioning and is not attributable to other conditions like intellectual disability. Co-occurring difficulties do not exclude a DLD diagnosis. The terminology seeks to improve identification and provision of services for children with language disorders.