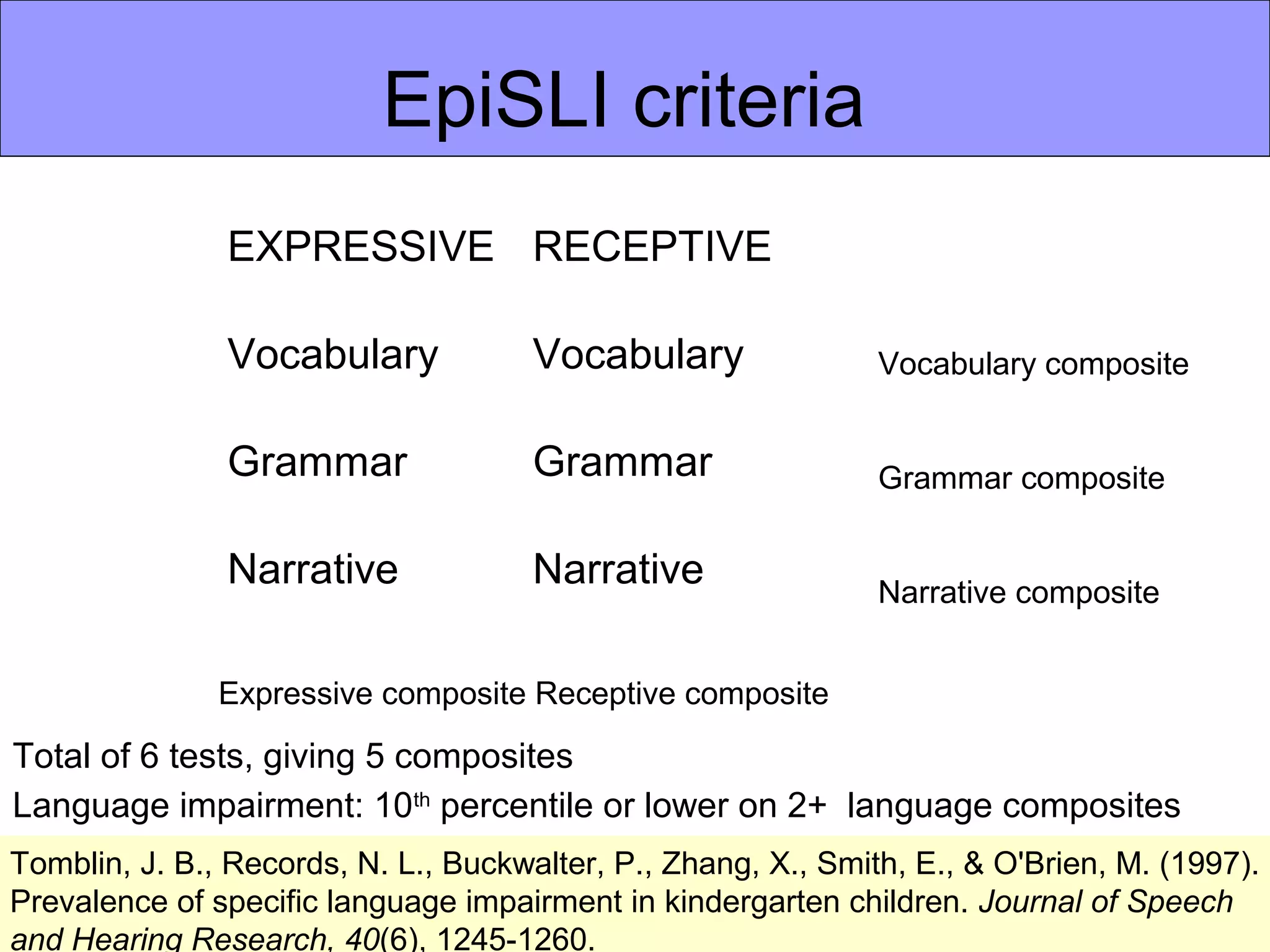

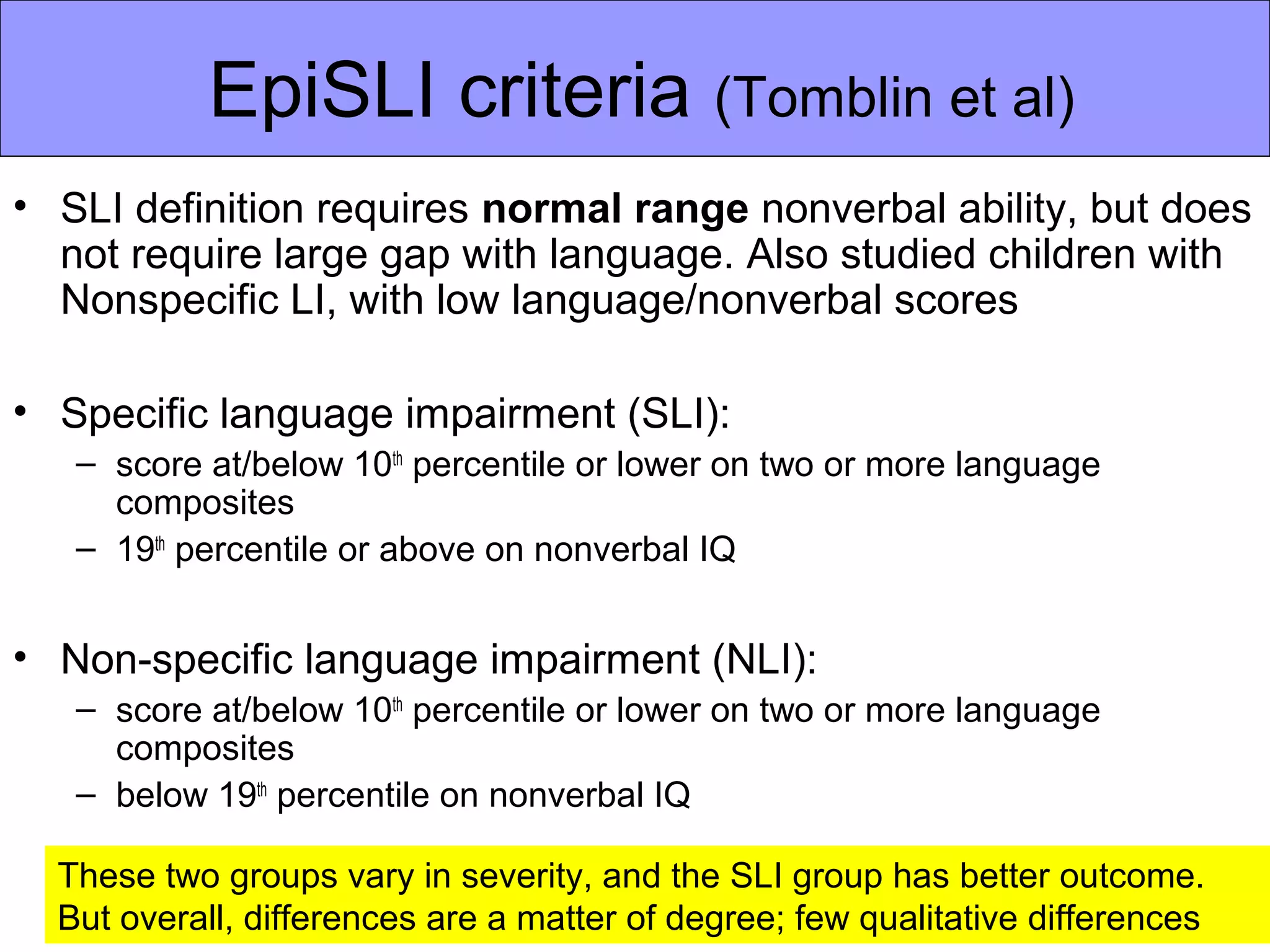

Specific language impairment (SLI) is identified in children when their language development falls significantly behind peers despite having normal nonverbal abilities, hearing, and environment. SLI is assessed through parental reports, direct observation of the child's communication, and standardized language tests in areas like vocabulary, grammar, and narrative skills. A child is identified as having SLI if they score below the 10th percentile on two or more standardized language assessments and have average nonverbal problem-solving skills. Assessing both language and nonverbal abilities provides a comprehensive evaluation of a child's communication development and needs.