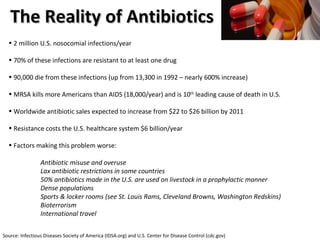

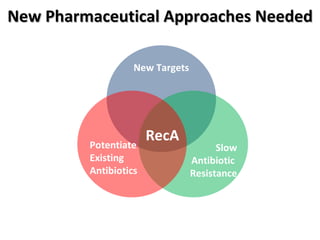

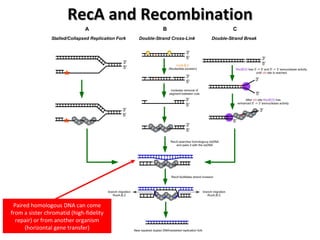

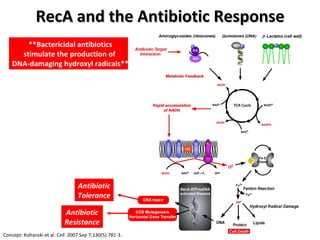

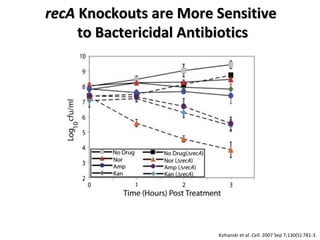

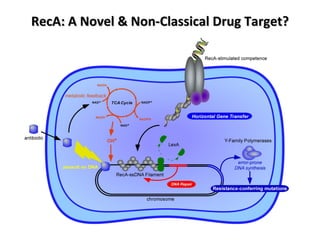

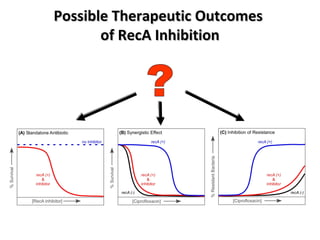

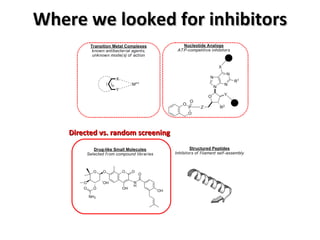

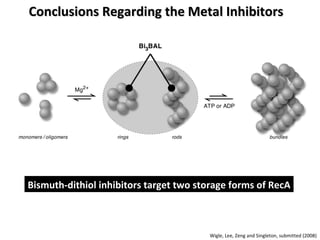

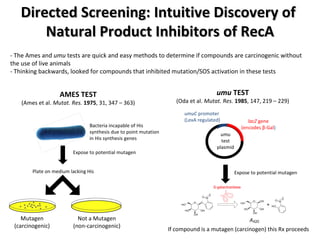

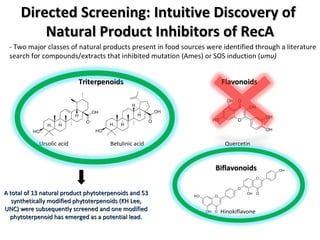

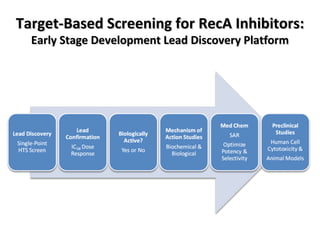

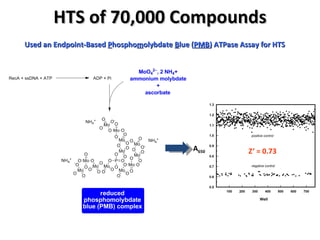

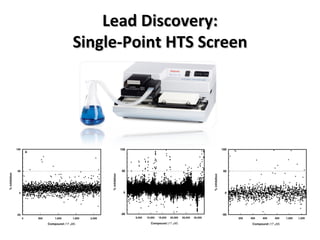

The document discusses the growing problem of antibiotic resistance and potential new approaches to addressing it. It notes that 2 million nosocomial infections occur in the US each year, 70% of which are resistant to at least one drug. 90,000 people die from these infections annually, a nearly 600% increase since 1992. The document then examines RecA, a bacterial protein involved in DNA repair, as a potential new target for antibiotics. It summarizes research investigating various compounds that inhibit RecA's function and could help combat antibiotic resistance.

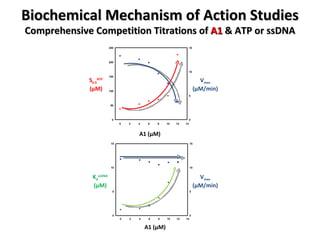

![Biochemical Mechanism of Action Studies Comprehensive Competition Titrations of A1 & ATP or ssDNA Michaelis-Menten Kinetics modified for cooperativity R = [RecA] S 0.5 ≈ K m R = [RecA] n = DNA/RecA stoichiometry (nts/monomer) D = [DNA] in nts K d = RecA-DNA binding dissociation constant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/WigleCICBDDDec162008forLinkedin-123506419281-phpapp02/85/RecA-foscused-antibacterial-screening-33-320.jpg)