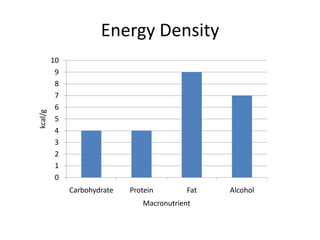

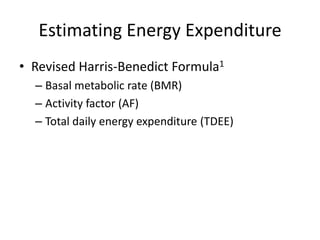

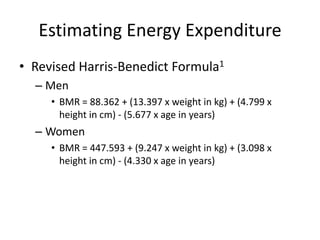

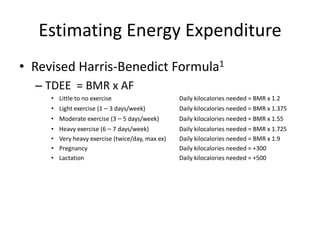

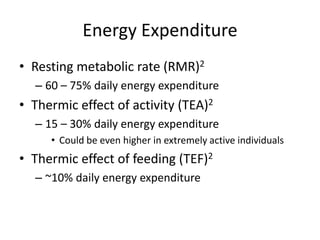

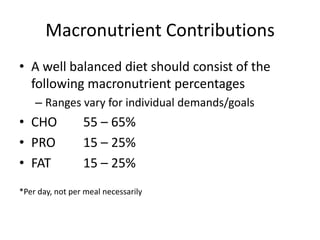

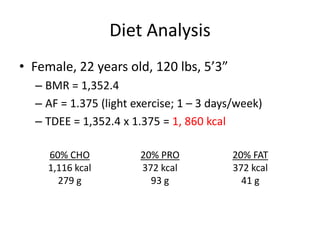

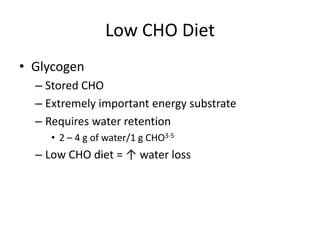

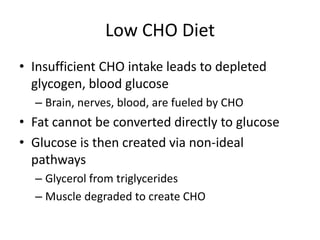

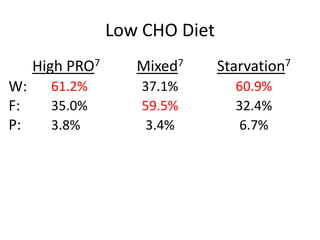

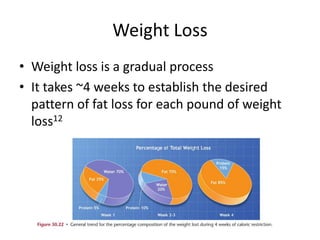

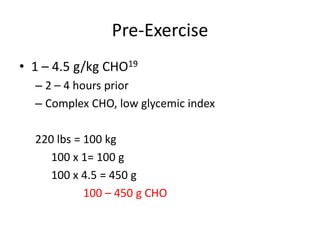

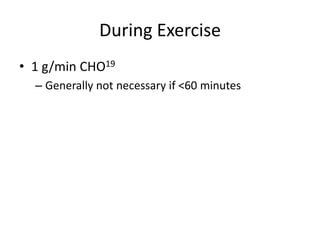

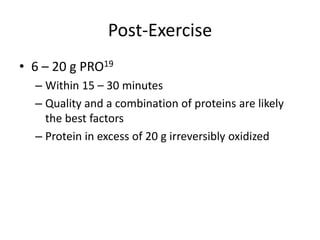

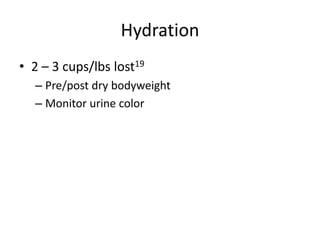

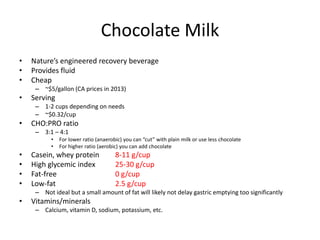

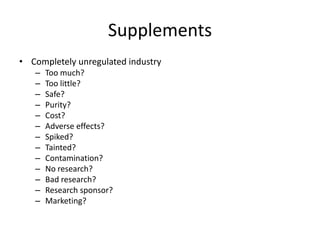

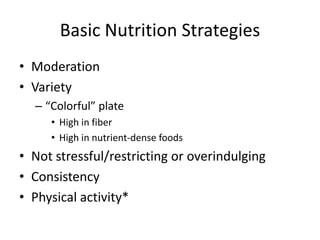

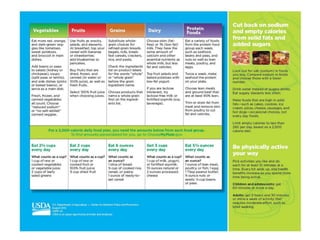

This document discusses nutrition strategies for performance and weight control. It provides information on estimating energy expenditure using the revised Harris-Benedict formula. It also discusses macronutrient contributions to the diet, strategies for weight loss and gain, and practical performance nutrition recommendations regarding pre, during, and post exercise nutrition. Supplements are noted to be an unregulated industry and lifestyle nutrition strategies emphasize moderation, variety, and consistency.