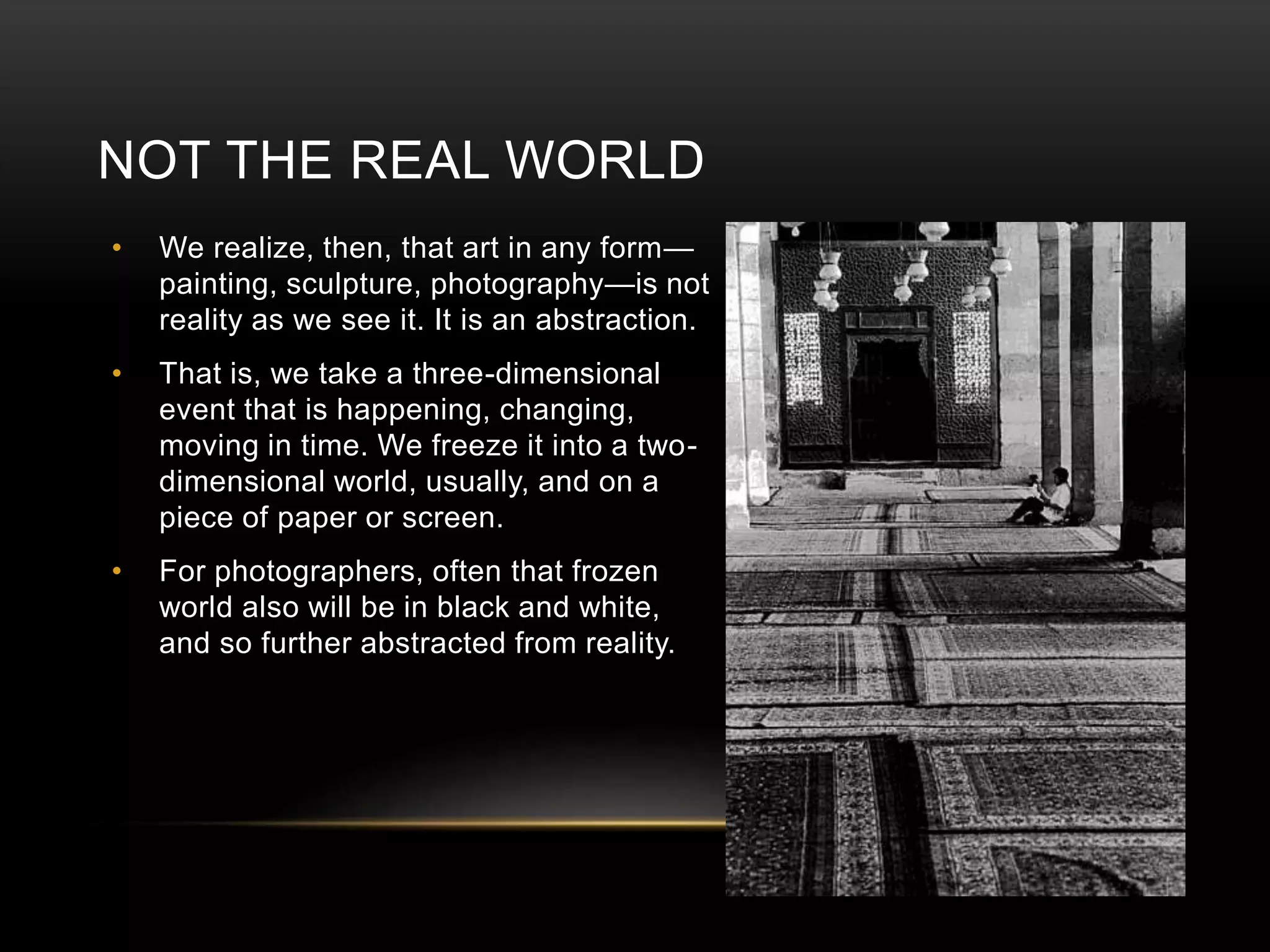

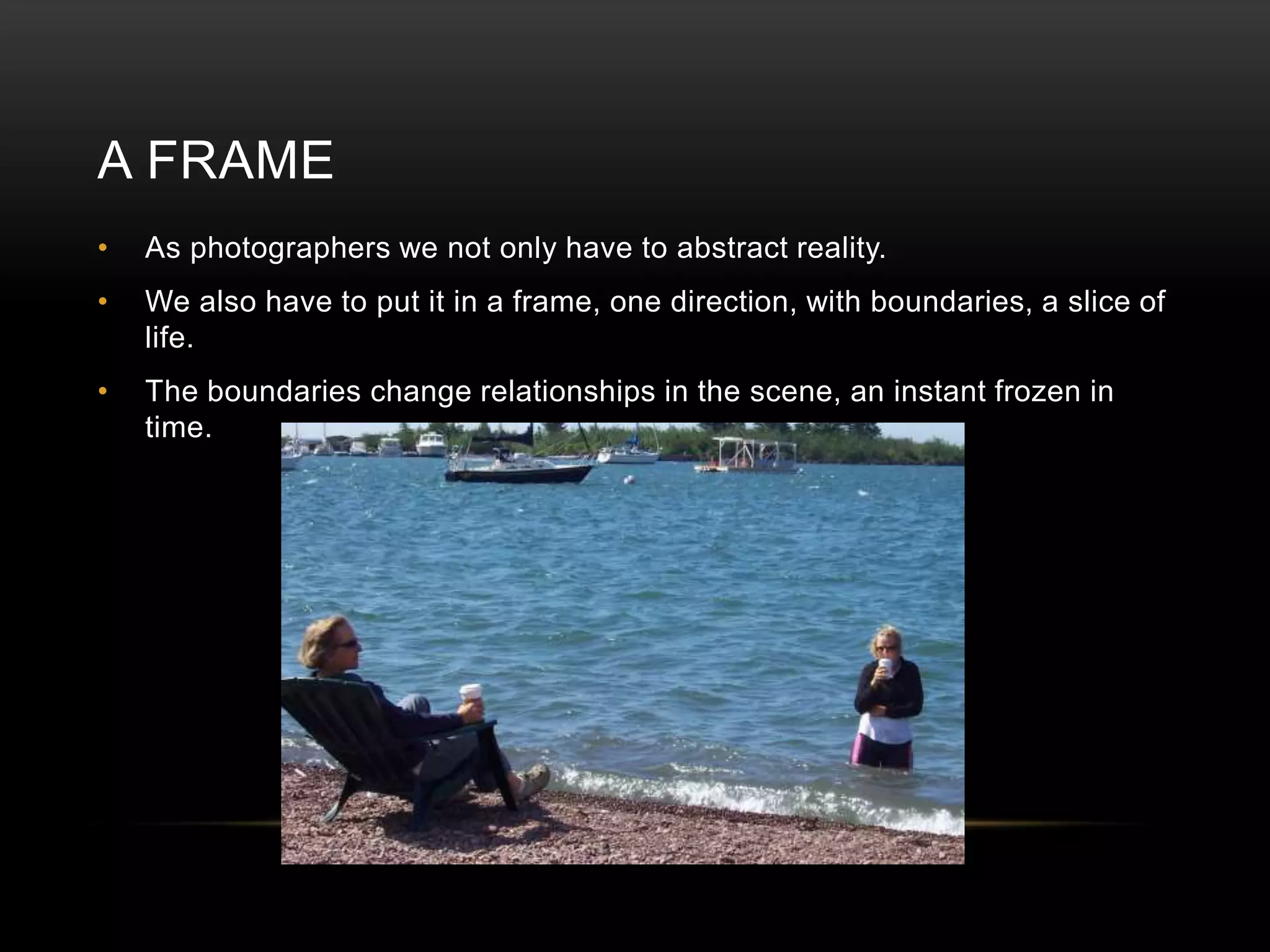

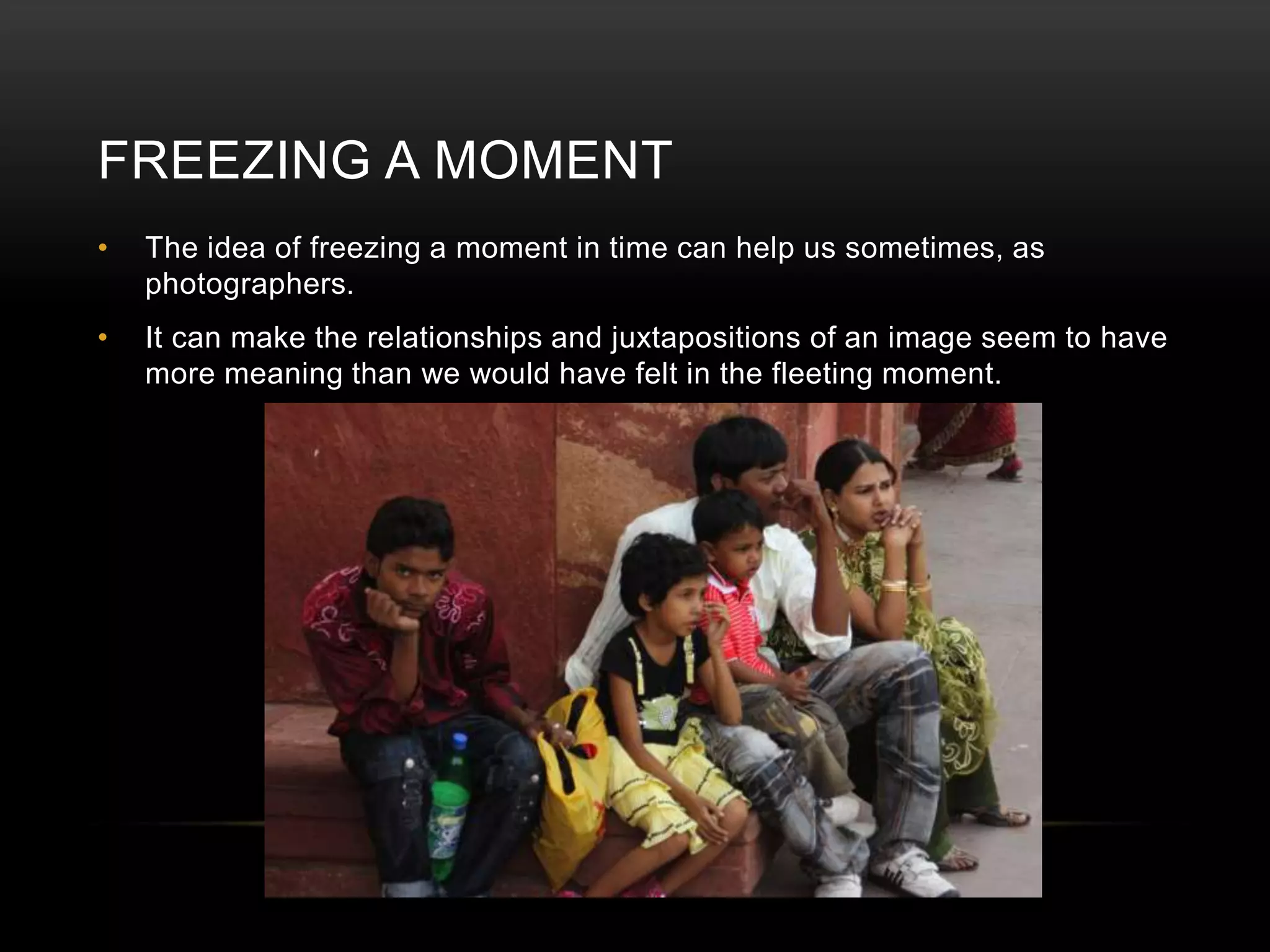

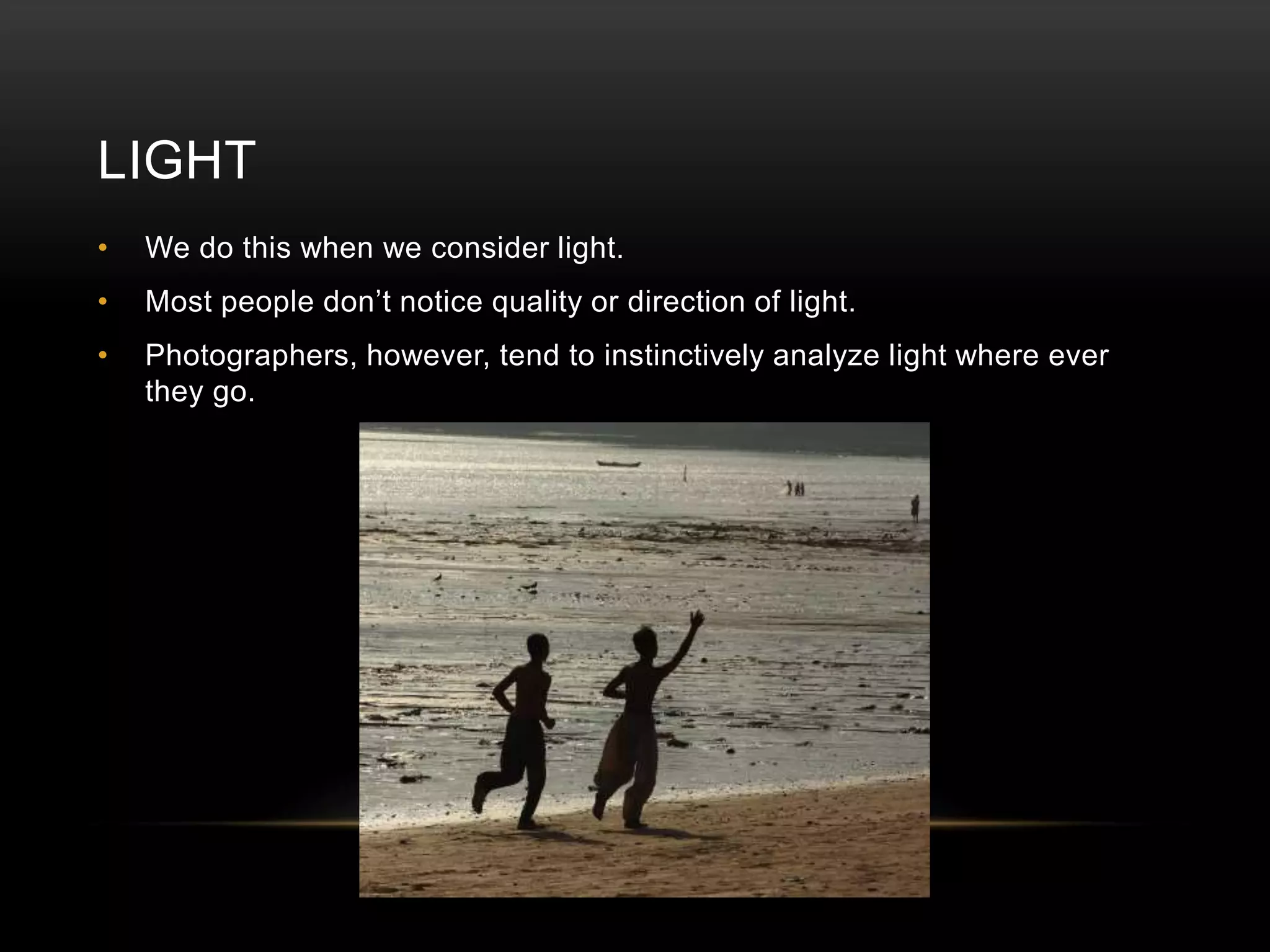

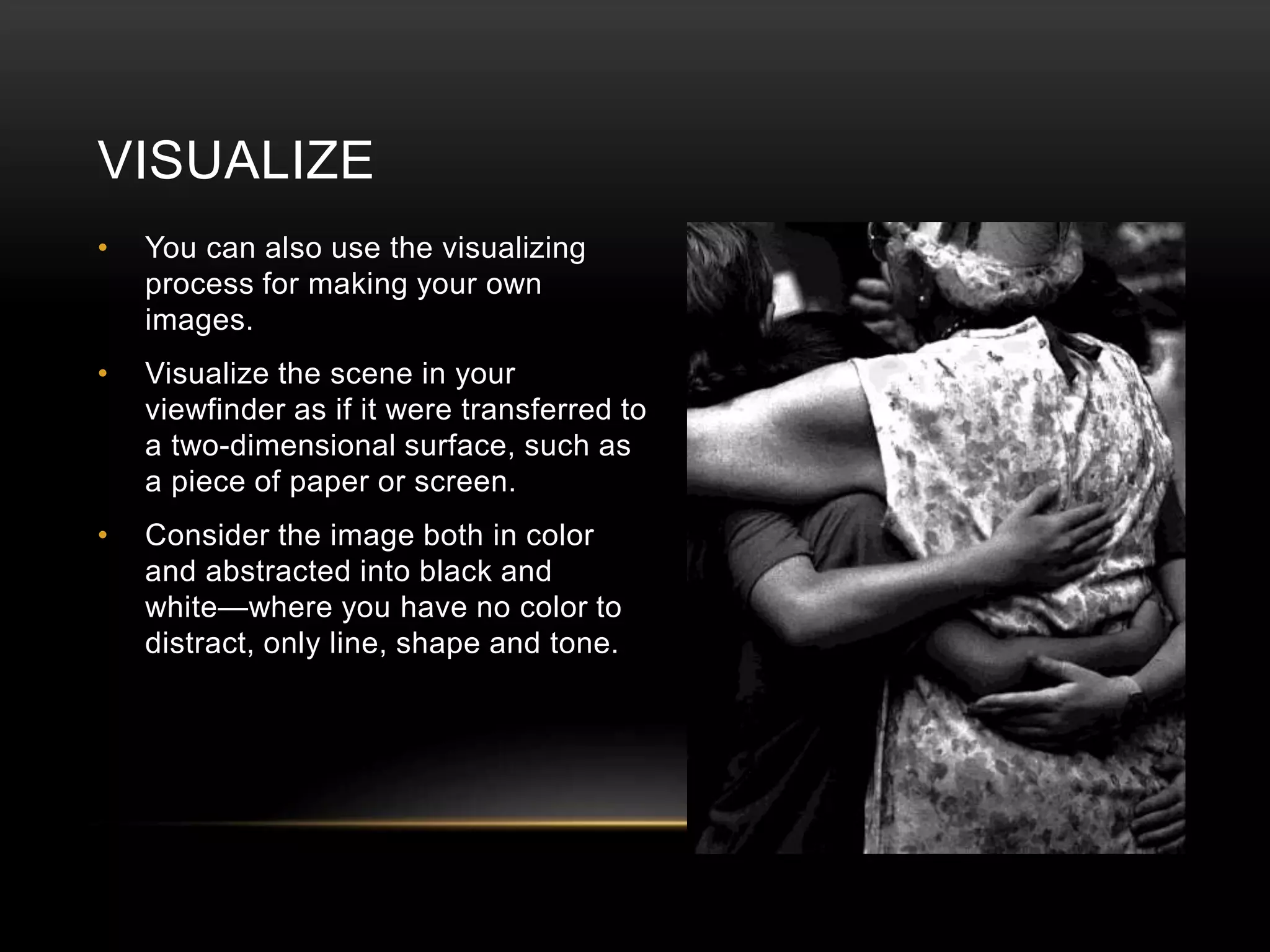

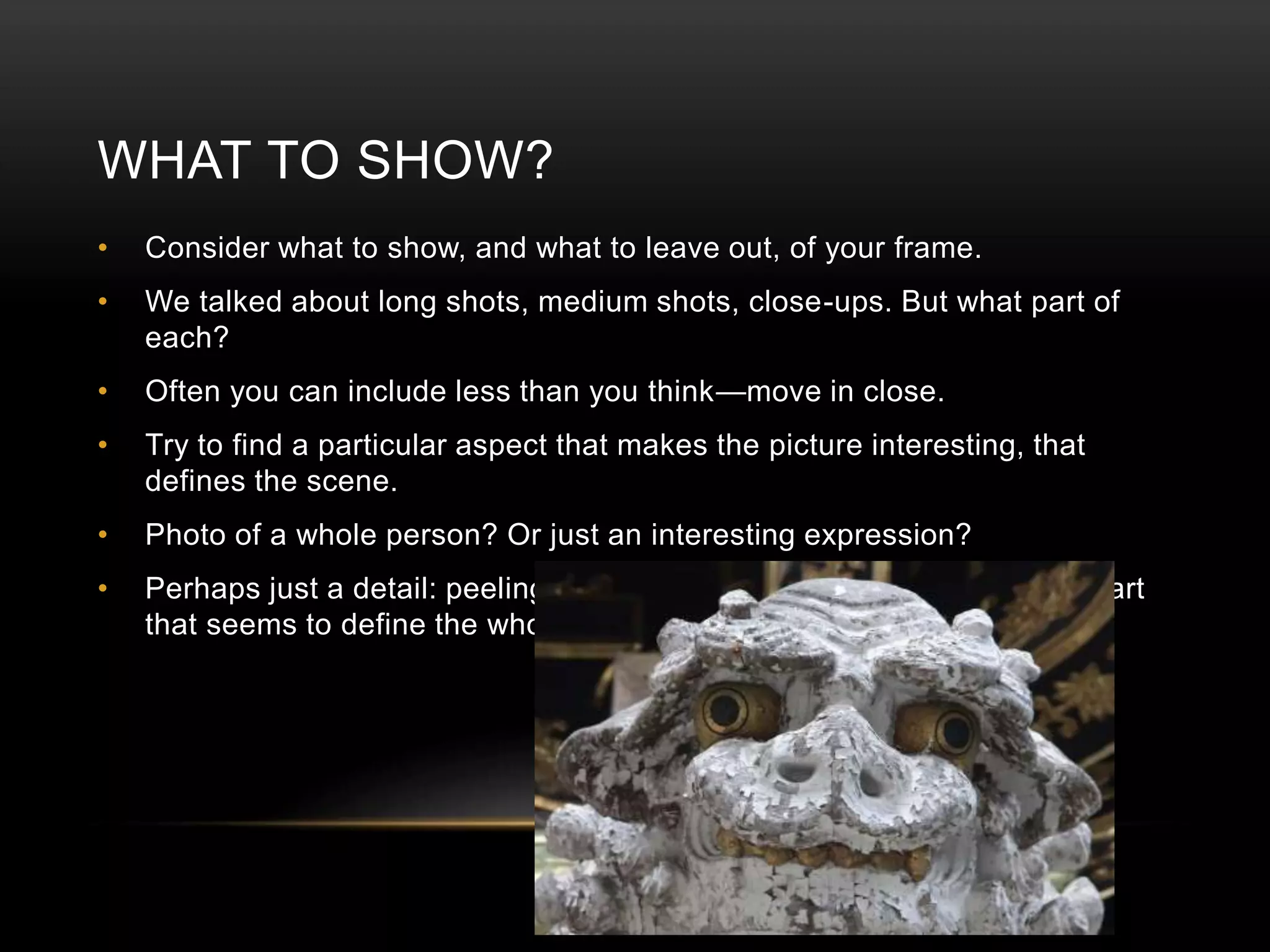

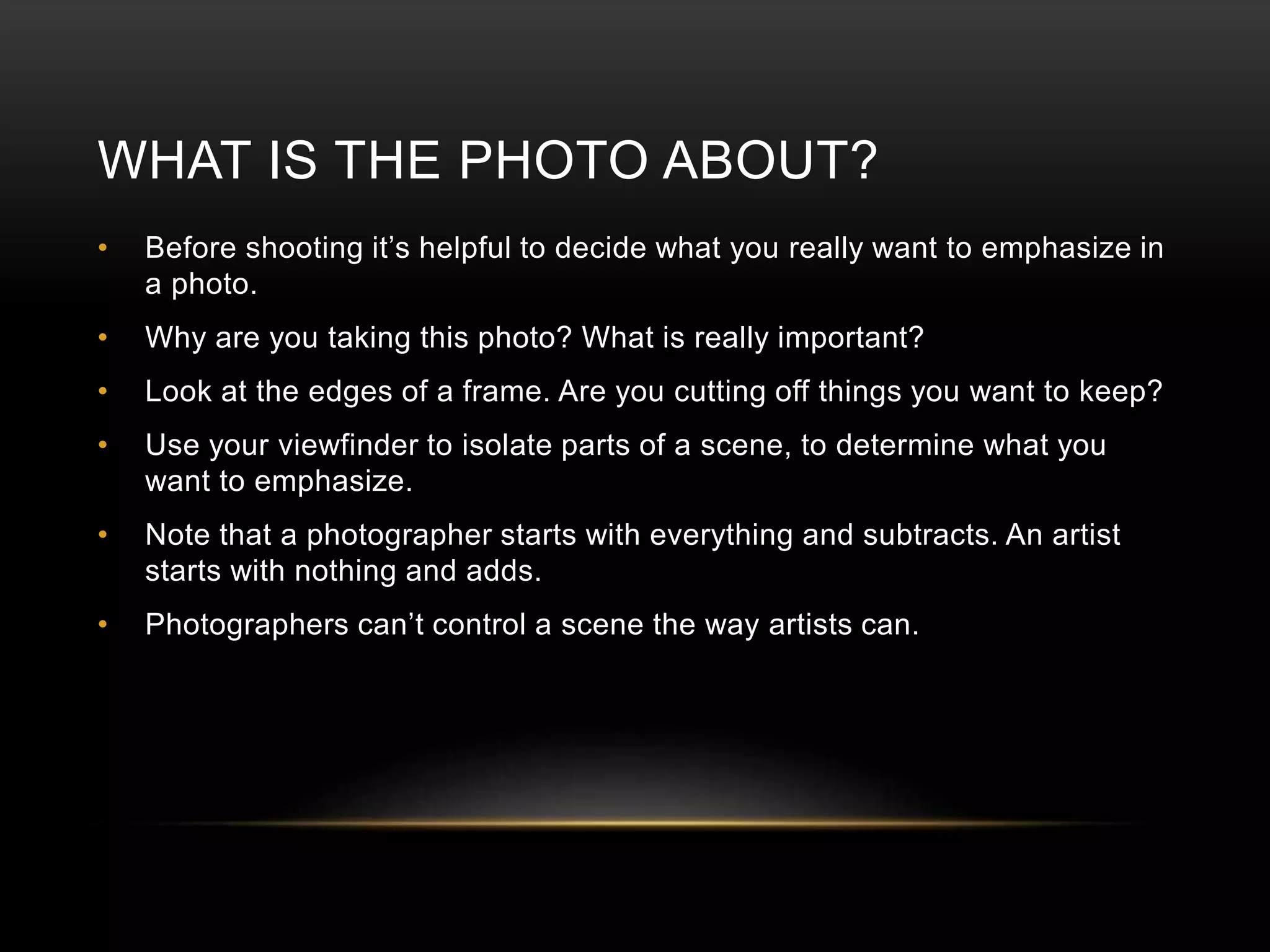

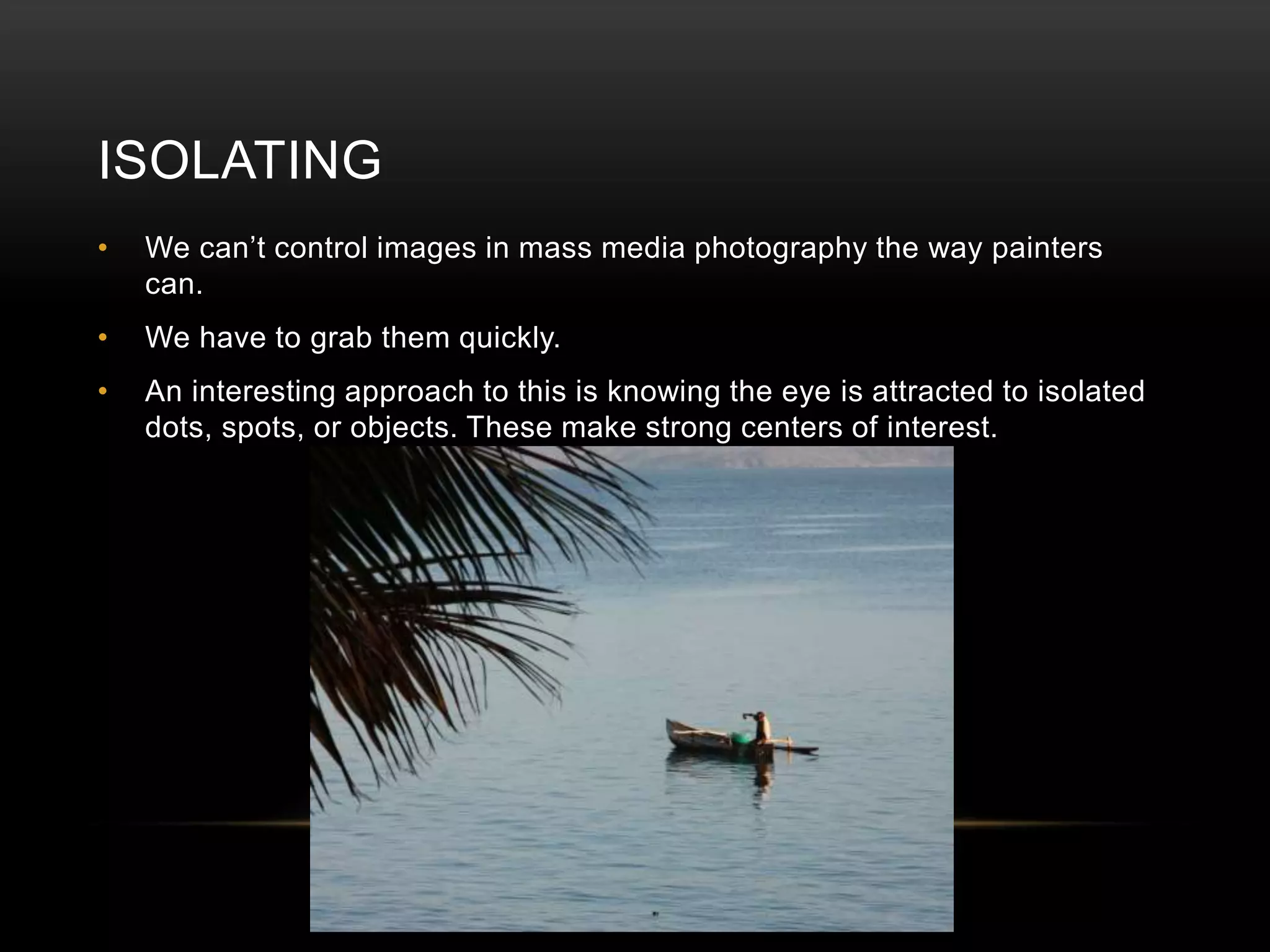

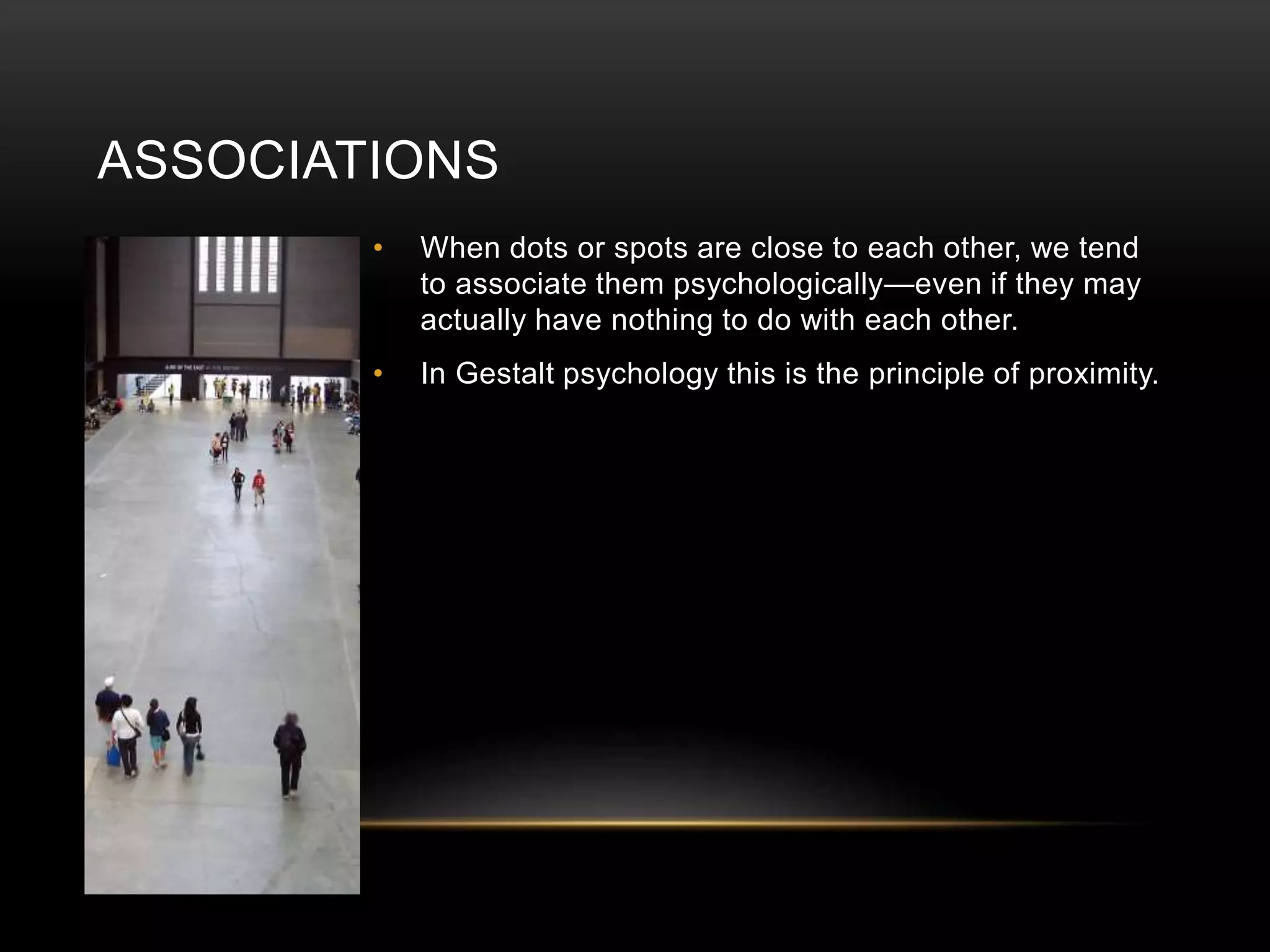

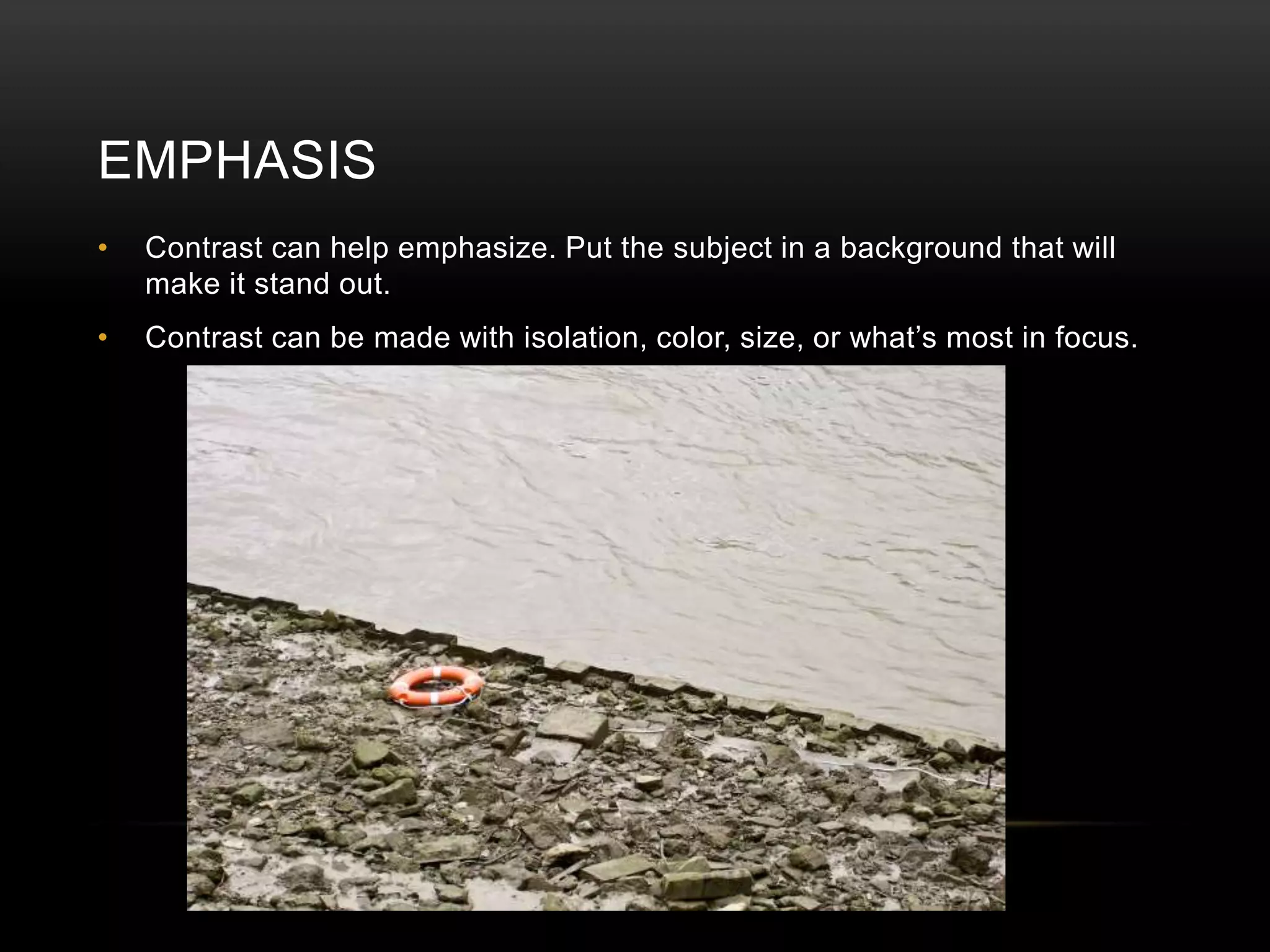

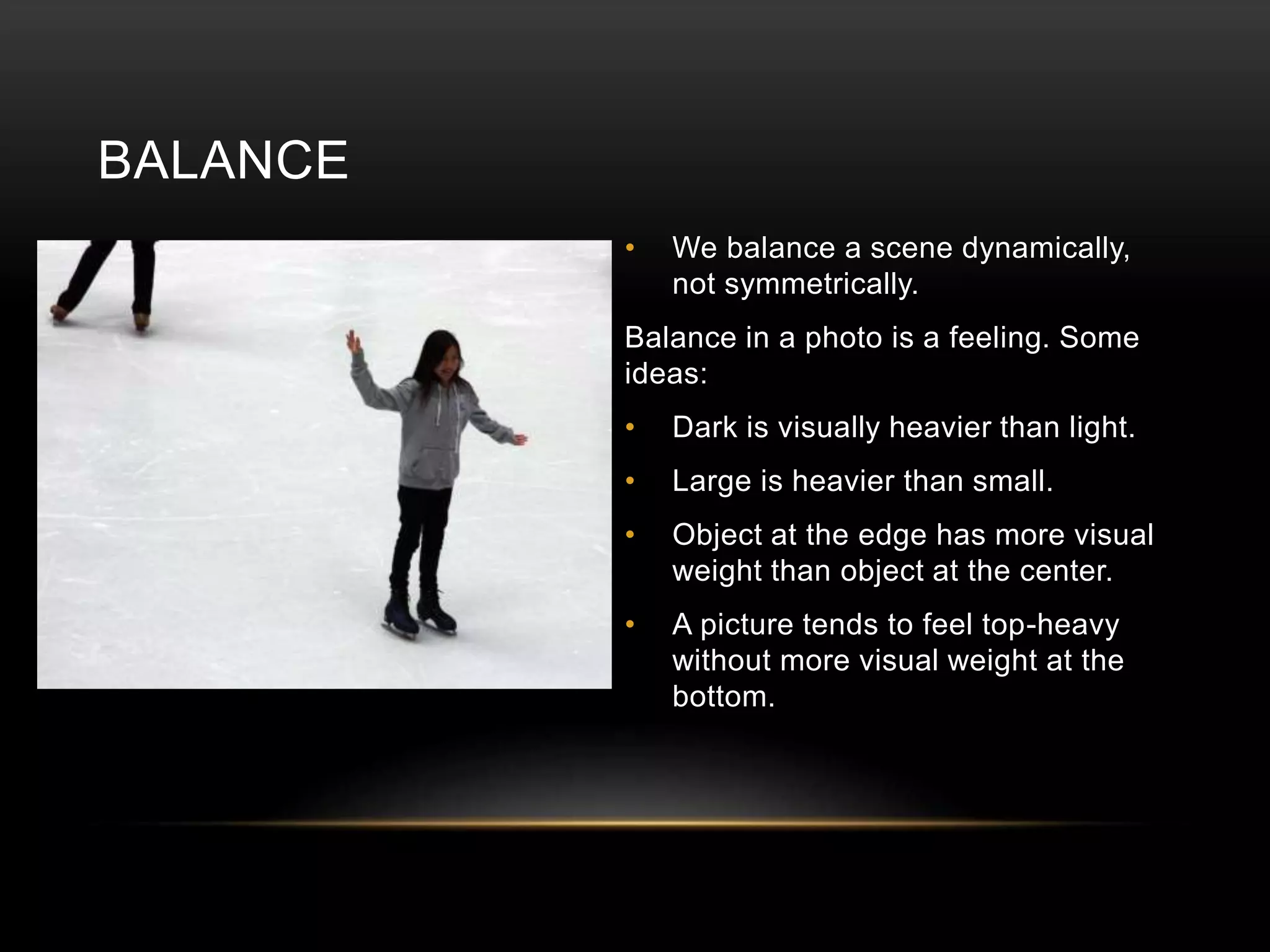

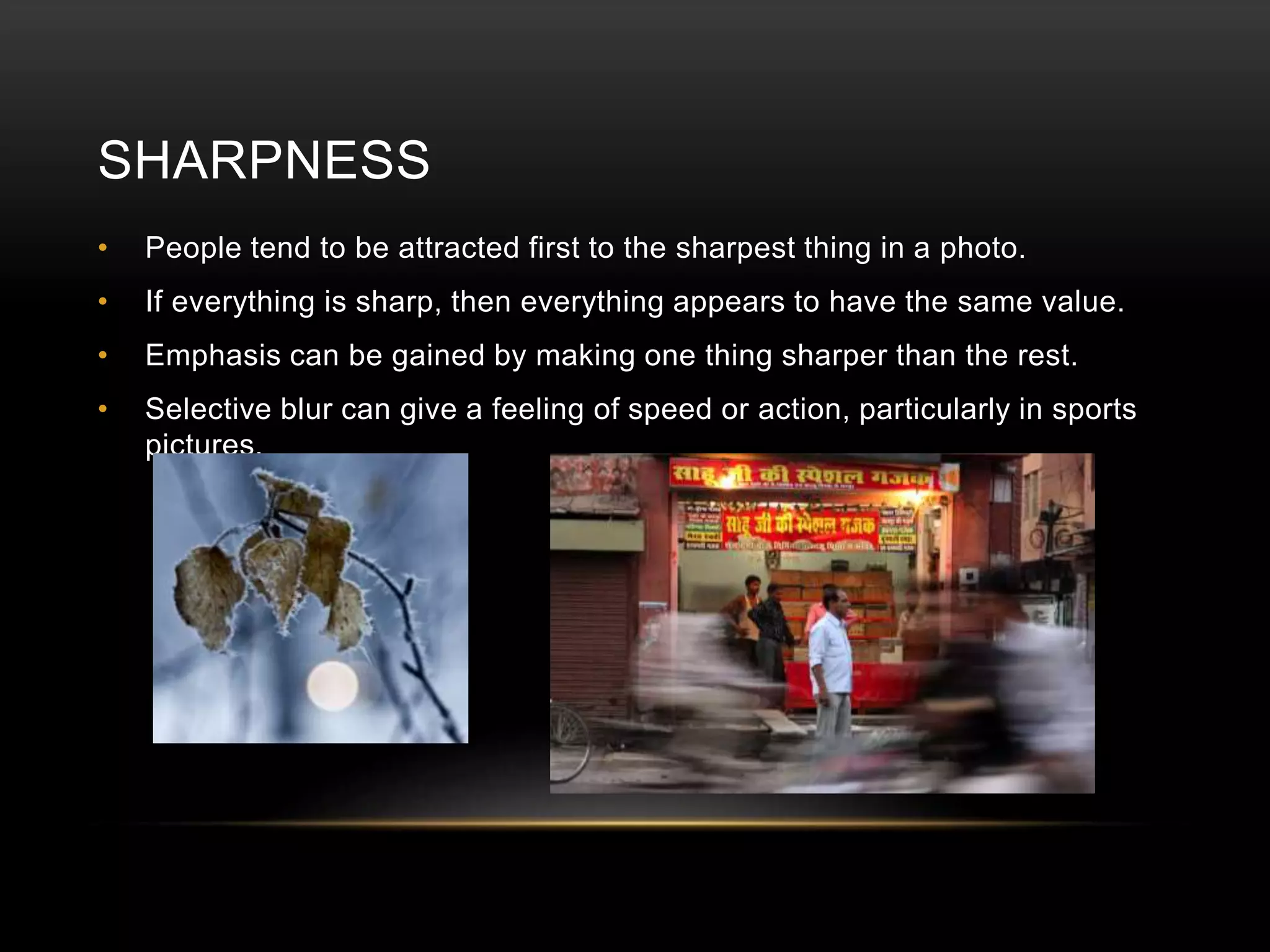

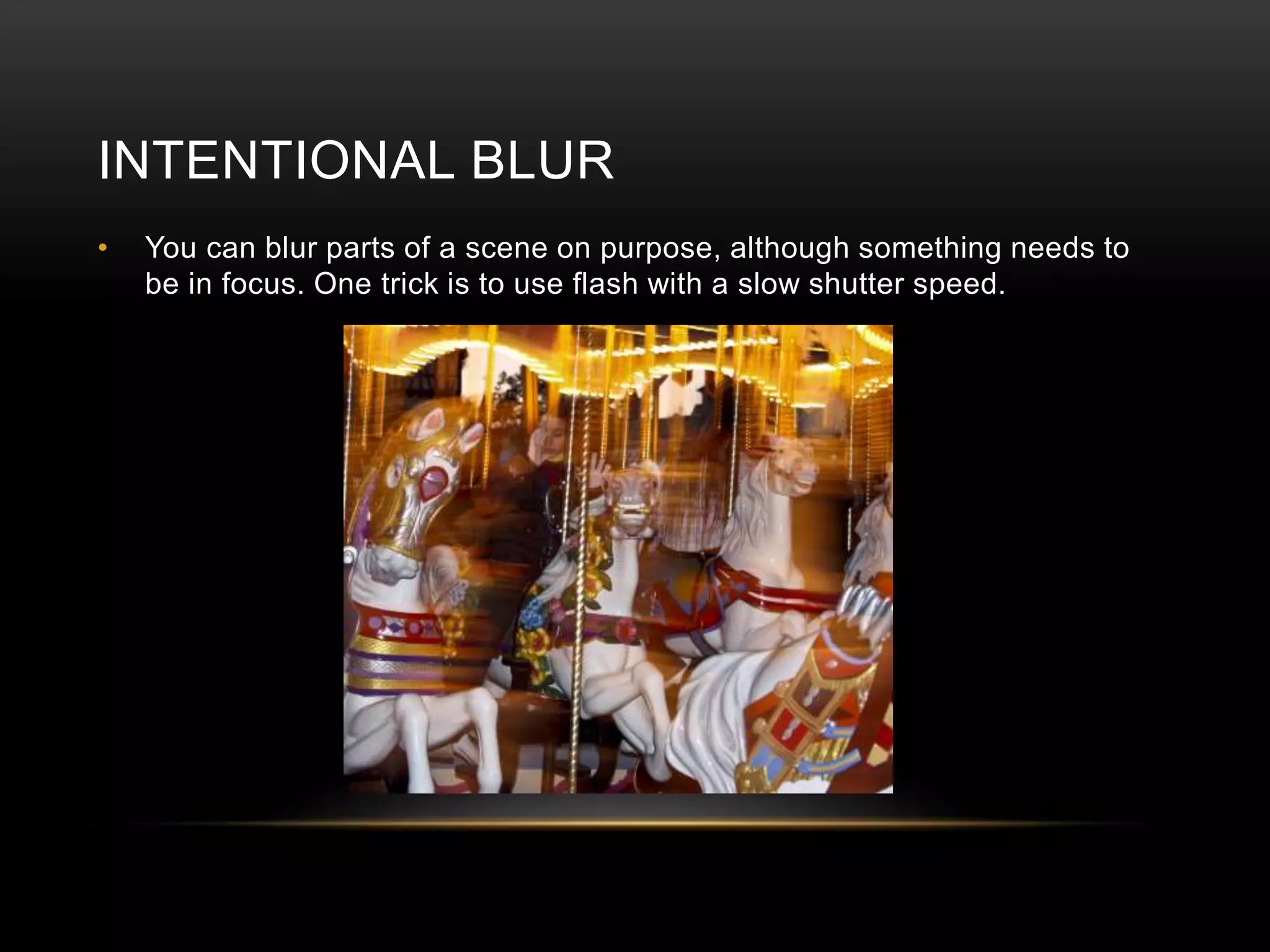

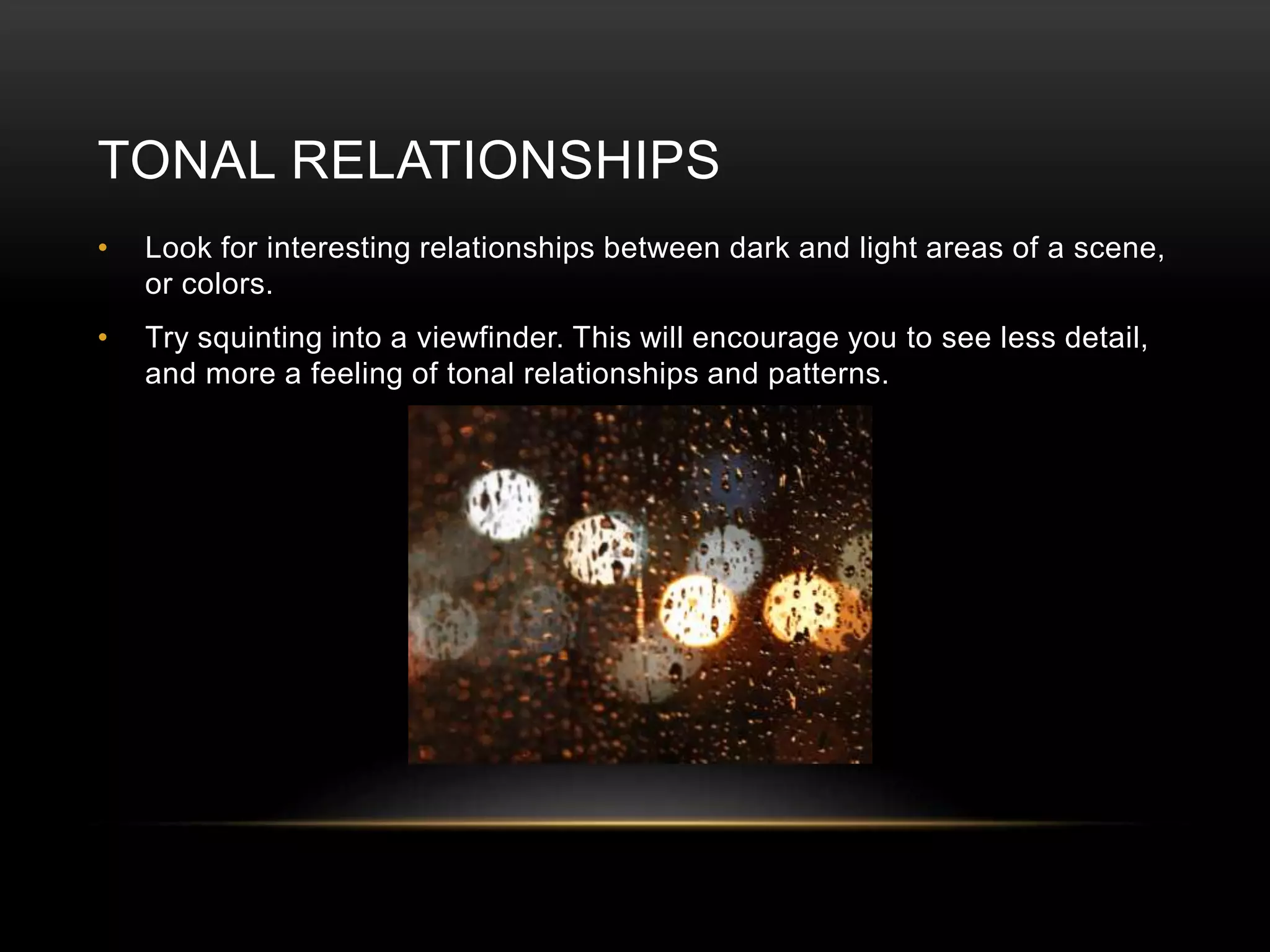

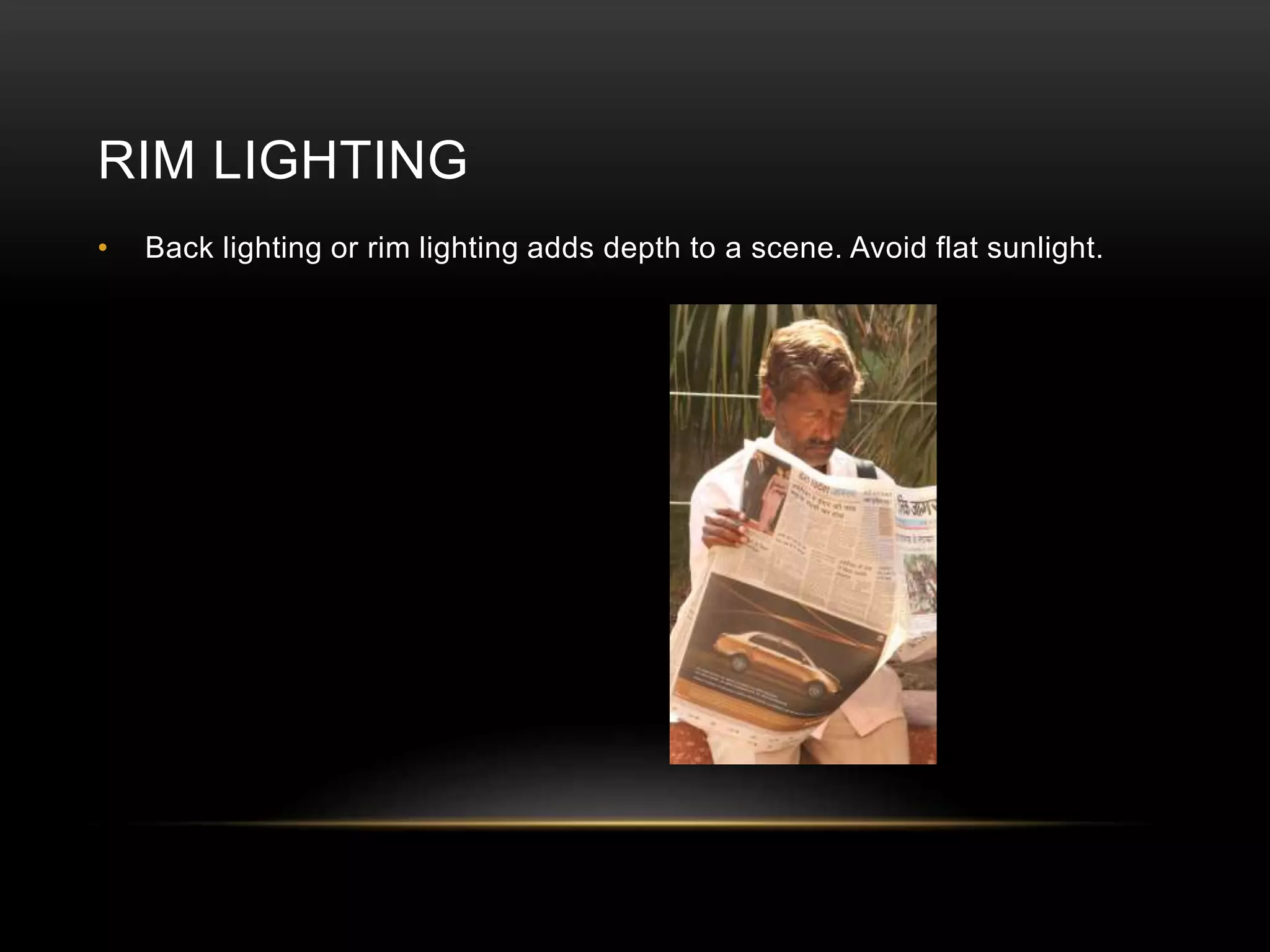

This document discusses ways of seeing and how to train oneself to truly observe the visual world. It explains that most people do not actively notice the shapes, patterns, colors and textures around them. Learning to draw or take photos requires analyzing scenes in new ways, as these mediums create abstracted representations rather than capturing objective reality. The document provides tips for photographers to learn how to see, such as paying attention to light, isolating subjects of emphasis, considering backgrounds, and using techniques like selective focus and rim lighting to create visual interest and depth.