This document is the 21st edition of Black's Veterinary Dictionary. It has been comprehensively updated from the 20th edition, with many new and amended entries to reflect developments in fields such as medication, newly identified conditions, and emerging diseases. A major addition is entries describing popular dog and cat breeds and their inheritable conditions. The dictionary has been a primary reference for veterinary practitioners, students, farmers and pet owners since its first publication in 1928.

![blood. It is used as a measure of liver damage in

dogs and cats.

Alaskan Malamute

A breed of dog developed from the husky.

Dwarfism (chondrodysplasia) is inherited in

some litters. Day blindness may also be inherited

and congenital haemolytic anaemia occurs.

Albinism

Albinism is a lack of the pigment melanin in

the skin – an inherited condition.

Albumins

(see PROTEINS; CONALBUMIN; ALBUMINURIA)

Albuminuria

The presence of albumin in the urine: one

of the earliest signs of NEPHRITIS and cystitis

(see URINARY BLADDER, DISEASES OF).

Alcohol Poisoning

Acute alcoholism is usually the result of too

large doses given bona fide, but occasionally the

larger herbivora and pigs eat fermenting wind-falls

in apple orchards; or are given or obtain,

fresh distillers’ grains, or other residue permeat-ed

with spirit, in such quantities that the ani-mals

become virtually drunk. In more serious

cases they may become comatose.

Aldosterone

This is a hormone secreted by the adrenal

gland. Aldosterone regulates the electrolyte

balance by increasing sodium retention and

potassium excretion. (See CORTICOSTEROIDS.)

Aldrin

A persistent insecticide; a chlorinated hydrocar-bon

used in agriculture and formerly in farm

animals. Its persistence has prevented its veteri-nary

use. Signs of toxicity include blindness,

salivation, convulsions, rapid breathing. (See

GAME BIRDS.)

Aleutian Disease

First described in 1956 in the USA, this disease

of mink also occurs in the UK, Denmark,

Sweden, New Zealand and Canada.

Mink

Signs include: failure to put on weight or even

loss of weight; thirst; the presence of undigested

food in the faeces – which may be tarry. Bleeding

from the mouth and anaemia may also be

observed. Death usually follows within a month.

Ferrets In these animals the disease is charac-terised

by a persistent viraemia.

Algae Poisoning 15

Signs include: loss of weight; malaise; chronic

respiratory infection; and paresis or paraplegia.

Bleeding from the mouth and anaemia may

also be observed. Death usually follows within

a month. The disease can be confused with the

later stages of rabies.

Diagnosis In ferrets the counter-current

electrophoresis test has been used.

Alexin

(see COMPLEMENT)

Alfadalone

(see ALFAXALONE)

Alfaxalone

Used in combination with alfadalone (in Saffan

[Schering-Plough]) as a general anaesthetic in

cats; it must not be used in dogs. Given by

intravenous injection, It produces sedation in

9 seconds and anaesthesia after 25 seconds. It is

also given by deep intramuscular injection as an

induction for general anasthesia for long opera-tions.

It must not be given with other injectable

anaesthetics.

Algae

Simple plant life of very varied form and size,

ranging from single-cell organisms upwards to

large seaweed structures. Algae can be a nui-sance

on farms when they block pipes or clog

nipple drinkers. This happens especially in

warm buildings, where either an antibiotic

or sugar is being administered to poultry via

the drinking water. Filters may also become

blocked by algae.

The colourless Prototheca species are patho-genic

for both animals (cattle, deer, dogs,

pigs) and man. (See MASTITIS IN COWS – Algal

mastitis.)

The non-toxic algae of the Spirulina group

are used in the feed of some ornamental fish.

Algae Poisoning

Toxic freshwater algae, characteristically blue-green

in colour, are found in summer on lakes

in numerous locations, particularly where water

has a high phosphate and nitrate content

derived from farm land. Formed by the summer

blooms of cyanobacteria, they can form an oily,

paint-like layer several cm thick. Deaths have

occurred in cattle and sheep drinking from

affected water; photosensitivity is a common

sign among survivors. Dogs have also been

affected.

The main toxic freshwater cyanobacteria are

strains of the unicellular Microcystis aeruginosa,

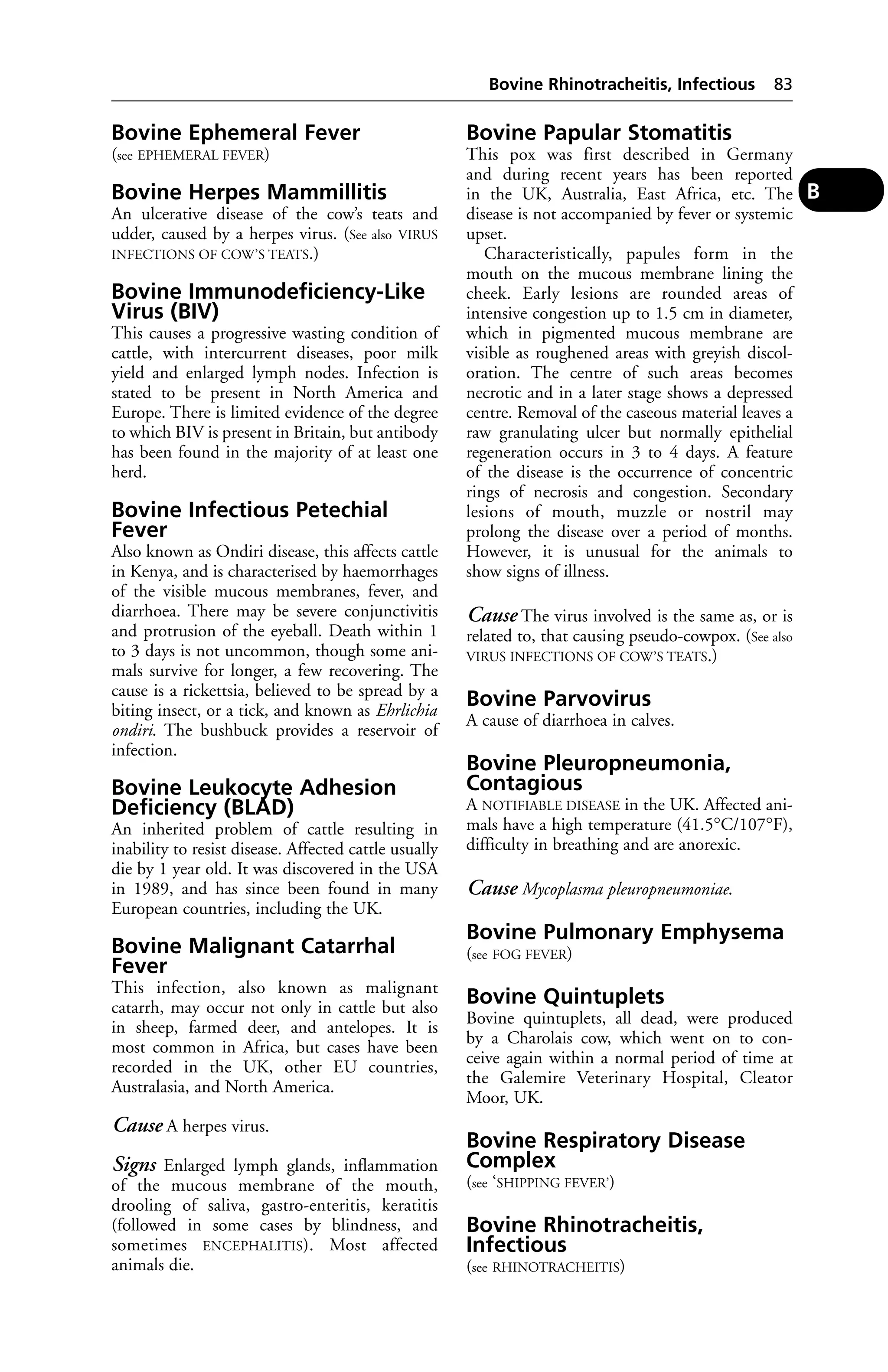

A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veterinarydictionary21stedition-140828090128-phpapp02/75/Veterinary-dictionary-_21st_edition-24-2048.jpg)

![by harness or other tackle from keeping their

nostrils above the level of the water; or they may

become panic-stricken and swim away from

shore. Remarkable instances of the powers of

swimming that are naturally possessed by ani-mals

are on record; one example being that of a

heifer, which, becoming excited and frightened

on the southern banks of the Solway Firth,

entered the water and swam across to the

Scottish side, a distance of over 7 miles, and was

brought back the next day none the worse.

Recovery from drowning As soon as the

animal has been rescued from the water, it

should be placed in a position which will allow

water that has been taken into the lungs to run

out by the mouth and nostrils. Small animals

may be held up by the hind-legs and swung

from side to side. Larger ones should be laid on

their sides with the hindquarters elevated at a

higher level than their heads. If they can be

placed with their heads downhill, so much

the better. Pressure should be brought to bear

on the chest, by one person placing all their

weight on to the upper part of the chest wall, or

kneeling on this part. When no more fluid runs

from the mouth, the animal should be turned

over on to the opposite side and the process

repeated. No time should be lost in so doing,

especially if the animal has been in the water for

some time. (See ARTIFICIAL RESPIRATION.)

After-treatment As soon as possible the ani-mal

should be removed to warm surroundings

and dried by wiping or by vigorous rubbing

with a rough towel. Clothing should be applied,

and the smaller animals may be provided with

1 or more hot-water bottles. The danger that has

to be kept in mind is that of pneumonia, either

from the water in the lungs or from the general

chilling of the body, and the chest should be

especially well covered. Sometimes the ingestion

of salt water leads to salt poisoning in dogs, or to

a disturbance of the digestive functions, and

appropriate treatment is necessary.

Drug Interactions

For those in which one drug enhances the

action of another, see SYNERGISM.

Adverse drug interactions or reactions are

indicated by manufacturers in the product data

sheet. Unexpected adverse reactions should be

reported to the manufacturer or the Veterinary

Medicines Directorate.

Drug Residues in Food

Drug residues in food are regarded as very

important from the point of view of public

Dubbing 205

health. The permitted maximum level of drugs

remaining in meat, milk or eggs after medicines

have been administered (maximum residue limit

[MRL]) is specified by regulation for all EU

countries. The manufacturer’s recommended

withdrawal period between the last dose of

drug administered and the animal going for

slaughter, or the milk or eggs being sold for

human consumption, must be observed.

Carcases in abattoirs are monitored to ensure

that the residues are within allowable limits.

(See also HORMONES IN MEAT PRODUCTION;

MILK – Antibiotics in; SLAUGHTER.)

Drug Resistance

(see under ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE; DIPPING; FLY

CONTROL)

Drugs, Disease Caused by

(see IATROGENIC DISEASE)

Dry Eye

(see EYE, DISEASES OF)

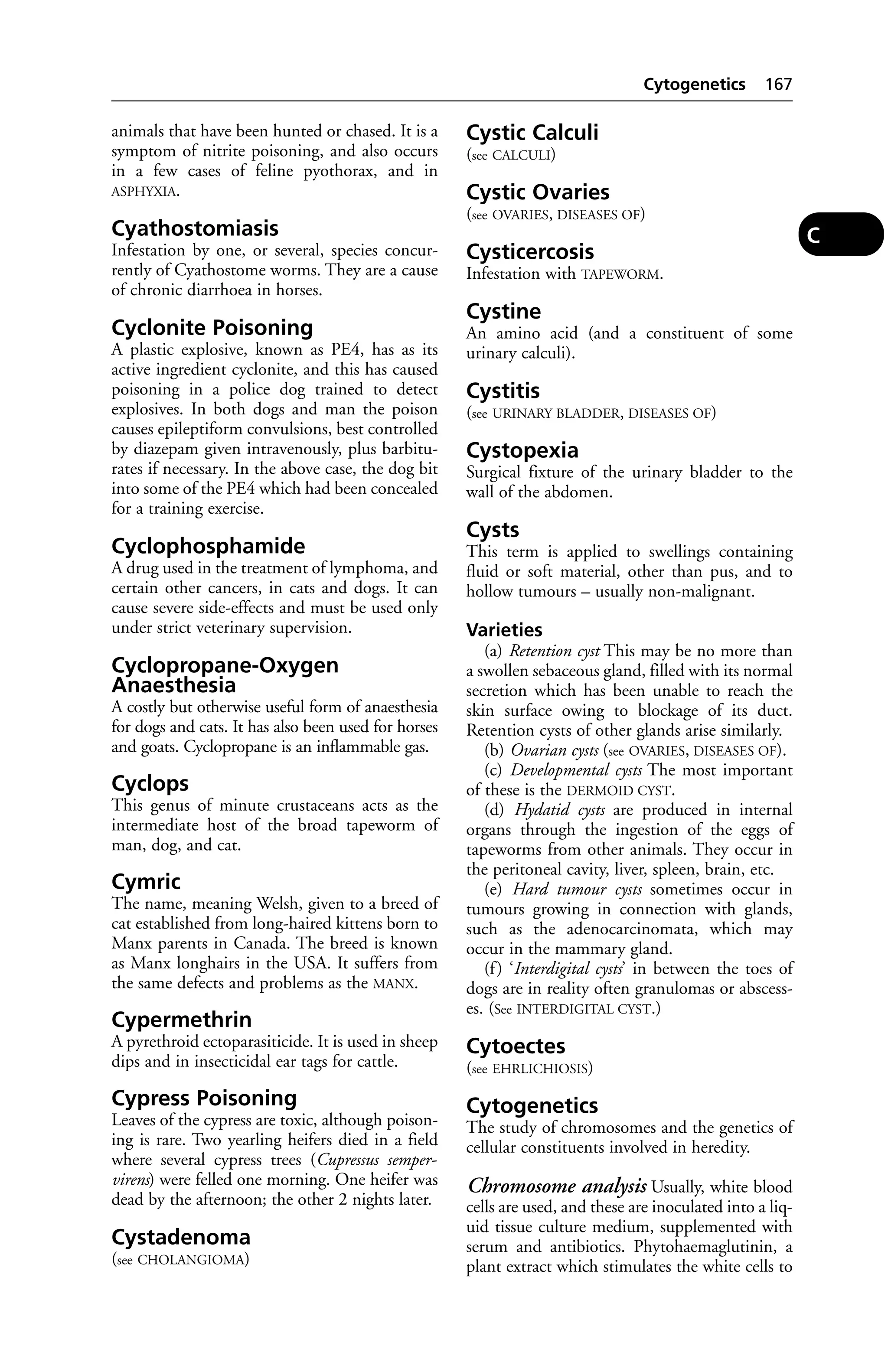

Dry Feeding

Dry feeding of meal may give rise to PARAKER-ATOSIS

in pigs; to ‘CURLED TONGUE’ in turkey

poults; and to ‘SHOVEL BEAK’ in chicks.

Dry, Firm and Dark (DFD)

Dry, firm and dark (DFD) describes the meat

of animals that have undergone stress in trans-port

before slaughter. The condition is a result

of glycogen depletion in the body. The meat’s

acidity is reduced but it is safe for consumption.

Dry Period

In cattle it is considered advisable on health

grounds that after a period of lactation, cows

should not be milked for about 8 weeks – the dry

period. Cows are dry in the weeks before calving.

Drying-off Cows

After milking out completely, the teats should

be washed and a dry-cow intramammary prepa-ration

inserted in each teat. The cows should be

inspected daily.

If possible, keep the cows on dry food or very

short pasture for 3 days after drying off.

Drysdale

A sheep with a very good fleece bred in New

Zealand. A natural mutation of the Romney, it

was identified and developed by Dr F. W. Dry

of Massey University.

Dubbing

Trimming of the comb imay be performed,

with scissors, by poultry keepers, and involves

D](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veterinarydictionary21stedition-140828090128-phpapp02/75/Veterinary-dictionary-_21st_edition-214-2048.jpg)

![may be affected, too. The infections cannot be

differentiated on clinical grounds; laboratory

tests are essential. (For signs, see under

ENCEPHALITIS.)

Control Mosquito control measures reduce

transmission of the disease; stabling horses dur-ing

outbreaks and applying insecticides can

help prevent mosquito attacks. Vaccines are

available for use in areas where the disease is

prevalent.

Public health In man, the disease takes the

form of an aseptic meningitis; outbreaks can be

very serious, and mortality can be high. In one

outbreak in Canada, 509 human cases were

reported, with 78 deaths; 12 of them among

children. Of 27 infants, many suffered brain

damage, resulting in convulsions, spasticity, and

hemiplegia.

Equine Filariasis

Infestation of horses with the filarid worm,

Seturia equina, the larvae being carried by mos-quitoes

and biting flies. It occurs in South and

Central Europe, and Asia.

Signs Malaise and anaemia, or fever, conjunc-tivitis,

and dropsical swellings.

Equine Gait Analysis

A combination of photographic recording and

computer analysis is used to study the motion

of the horse’s limbs as it trots or gallops on a

treadmill. The system was originally devised by

a Swiss, Bruno Kaegi. It helps to provide an

objective measurement of the degree of lame-ness

affecting a horse, and also a comparison

between the limbs.

Equine Genital Infections in the

Mare

A wide range of organisms may be found on

taking cervical swabs. Some may be harmless,

but others may cause abortion or disease in the

mare or transmit infection to the stallion.

CONTAGIOUS EQUINE METRITIS (CEM), a

NOTIFIABLE DISEASE, is an important uterine

infection described in a separate entry. It is

caused by Taylorella equigenitalis.

Other infections include beta haemolytic

streptoccoci, Klebsiella aerogenes, Pseudomonas

species (see also LISTERIOSIS; LEPTOSPIROSIS; BRU-CELLOSIS).

Fungal infections have rarely been

reported, and include Aspergillus fumigatus and

Candida albicans.

Abortion caused by the virus of equine

rhinopneumonitis has also occurred in the UK

Equine Infectious Anaemia 227

for several years, most outbreaks being associated

with imported or visiting mares.

Equine Herpesviruses

These include EHV 1, the equine rhinopneu-monitis

or ‘equine abortion’ virus which has

also caused ataxia and paresis. Primarily affect-ing

the respiratory system, EHV1 is the cause

of much illness in young horses. EHV 3 causes

equine coital exanthema. (EHV 2 may be

non-pathogenic.)

Equine Hydatid Disease

(see HYDATID DISEASE)

Equine Hyperlipaemia

A disease of ponies, with an average age of

9 years, affecting the liver, kidneys, and pan-creas.

Mortality may reach 67 per cent.

Equine Infectious Anaemia

A NOTIFIABLE DISEASE. Synonyms include:

pernicious equine anaemia, swamp fever, horse

malaria.

A contagious disease of horses and mules

during the course of which changes occur in the

blood, and rapid emaciation with debility and

prostration are evident. It occurs chiefly in the

Western States of America and the North-

Western Provinces of Canada, as well as in most

countries of Europe, and in Asia, and Africa.

The first case in the UK was reported from

Newmarket in 1975.

Cause A virus. The horse is commonly infect-ed

by biting insects, e.g. horse flies, stable flies,

mosquitoes. Infected grooming tools if they

cause an abrasion, syringes, hypodermic needles

(or even contaminated vaccines) are other

means of transmission. The virus may be pre-sent

in urine, faeces, saliva, nasal secretions,

semen, and milk.

The disease is prevalent in low-lying,

swampy areas, especially during spring and

summer months.

The virus may cause illness in man (who may

infect a horse); also in pigs.

Signs After an incubation period of 2 to

4 weeks, equine infectious anaemia gives rise

to intermittent fever (with a temperature of up to

41°C [106°F]), depression and weakness. Often

there are tiny haemorrhages on the lining of the

eyelids and under the tongue. Jaundice, swelling

of the legs and lower part of the abdomen, and

anaemia may follow. In acute cases, death is

common. In chronic cases there may be a recur-rence

of fever, loss of appetite, and emaciation.

E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veterinarydictionary21stedition-140828090128-phpapp02/75/Veterinary-dictionary-_21st_edition-236-2048.jpg)

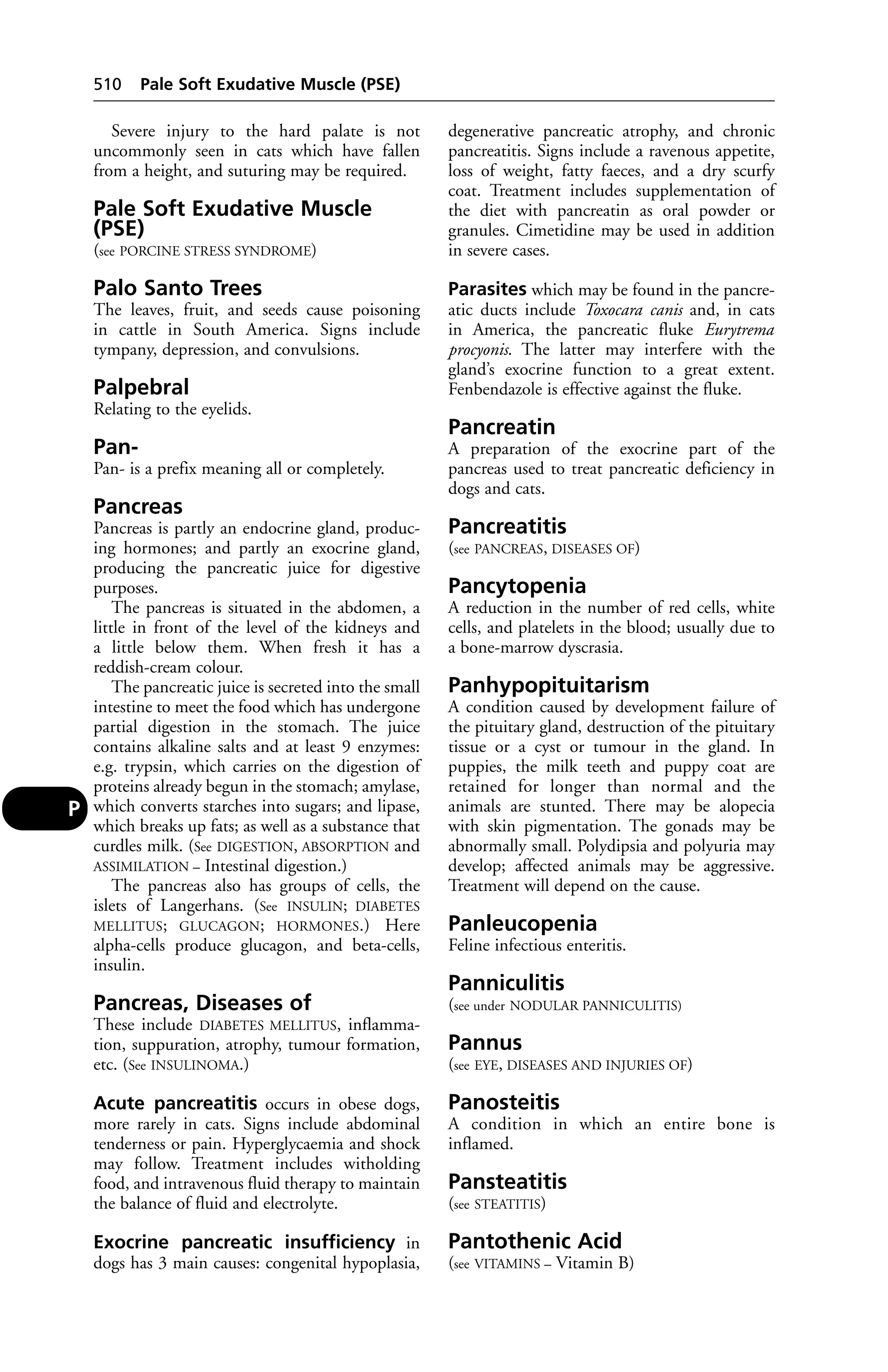

![Fatty Liver/Kidney Syndrome of Chickens (FLKS) 247

Intending farriers must undergo a 5-year

apprenticeship, including a period at an autho-rised

college, then take an examination for the

diploma of the Worshipful Company of Farriers

before they can practise independently. The

training is controlled by the Farriers Training

Council and a register of farriers kept by the

Farriers Registration Council, Sefton House,

Adam Court, Newark Road, Peterborough PE1

5PP. Its website is at www.farrier-reg.gov.uk.

Farrowing

The act of parturition in the sow.

Farrowing Crates

A rectangular box in which the sow gives birth.

Their use is helpful in preventing overlying of

piglets by the sow, and so in obviating one cause

of piglet mortality; however, they are far from

ideal. Farrowing rails serve the same purpose

but perhaps the best arrangement is the circular

one which originated in New Zealand. (See

ROUNDHOUSE.)

Work at the University of Nebraska suggests

that a round stall is better, because the conven-tional

rectangular one does not allow the sow to

obey her natural nesting instincts, and may give

rise to stress, more stillbirths and agalactia.

Farrowing Rates

In the sow, the farrowing rate after 1 natural

service appears to be in the region of 86 per

cent. Following a 1st artificial insemination,

the farrowing rate appears to be appreciably

lower, but at the Lyndhurst, Hants AI Centre,

a farrowing rate of about 83 per cent was

obtained when only females which stood firm-ly

to be mounted at insemination time were

used. The national (British) average farrowing

rate has been estimated at 65 per cent for a

1st insemination.

Fascia

Sheets or bands of fibrous tissue which enclose

and connect the muscles.

Fascioliasis

Infestation with liver flukes.

Fat

Normal body fat is, chemically, an ester of 3

molecules of 1, 2, or 3 fatty acids, with 1 mol-ecule

of glycerol. Such fats are known as glyc-erides,

to distinguish them from other fats and

waxes in which an alcohol other than glycerol

has formed the ester. (See also LIPIDS [which

include fat]; FATTY ACIDS. For fat as a tissue, see ADI-POSE

TISSUE. A LIPOMA is a benign fatty tumour.

For other diseases associated with fat, see STEATI-TIS;

FATTY LIVER SYNDROME; OBESITY, DIET.)

Fat Supplements

In poultry rations these can lead to TOXIC FAT

DISEASE. (See LIPIDS for cattle supplement; also

ECZEMA in cats.)

Fatigue

(see EXERCISE; MUSCLE; NERVES)

Fatty Acids

These, with an alcohol, form FAT. Saturated

fatty acids have twice as many hydrogen atoms

as carbon atoms, and each molecule of fatty

acid contains 2 atoms of oxygen. Unsaturated

fatty acids contain less than twice as many

hydrogen atoms as carbon items, and 1 or more

pairs of adjacent atoms are connected by double

bonds. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are those in

which several pairs of adjacent carbon atoms

contain double bonds.

Fatty Degeneration

A condition in which there is an excess of fat in

the parenchyma cells of organs such as the liver,

heart, and kidneys.

Fatty Liver Haemorrhagic

Syndrome (FLHS)

This is a condition in laying hens which has

to be differentiated from FLKS (see next entry)

of high-carbohydrate broiler-chicks. Factors

involved include high carbohydrate diets, high

environmental temperatures, high oestrogen

levels, and the particular strain of bird. FLHS

in hens is improved by diets based on wheat as

compared with maize; whereas FLKS is aggra-vated

by diets based on wheat. Death is due to

haemorrhage from the enlarged liver.

Fatty Liver/Kidney Syndrome

of Chickens (FLKS)

A condition in which excessive amounts of fat are

present in the liver, kidneys, and myocardium.

The liver is pale and swollen, with haemorrhages

sometimes present, and the kidneys vary from

being slightly swollen and pale pink to being

excessively enlarged and white. Morbidity is

usually between 5 and 30 per cent.

Cause FLKS has been shown to respond to

biotin (see VITAMINS), and accordingly can be

prevented by suitable modification of the diet.

Signs A number of the more forward birds (usu-ally

2 to 3 weeks old) suddenly show symptoms

of paralysis. They lie down on their breasts with

F](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veterinarydictionary21stedition-140828090128-phpapp02/75/Veterinary-dictionary-_21st_edition-256-2048.jpg)