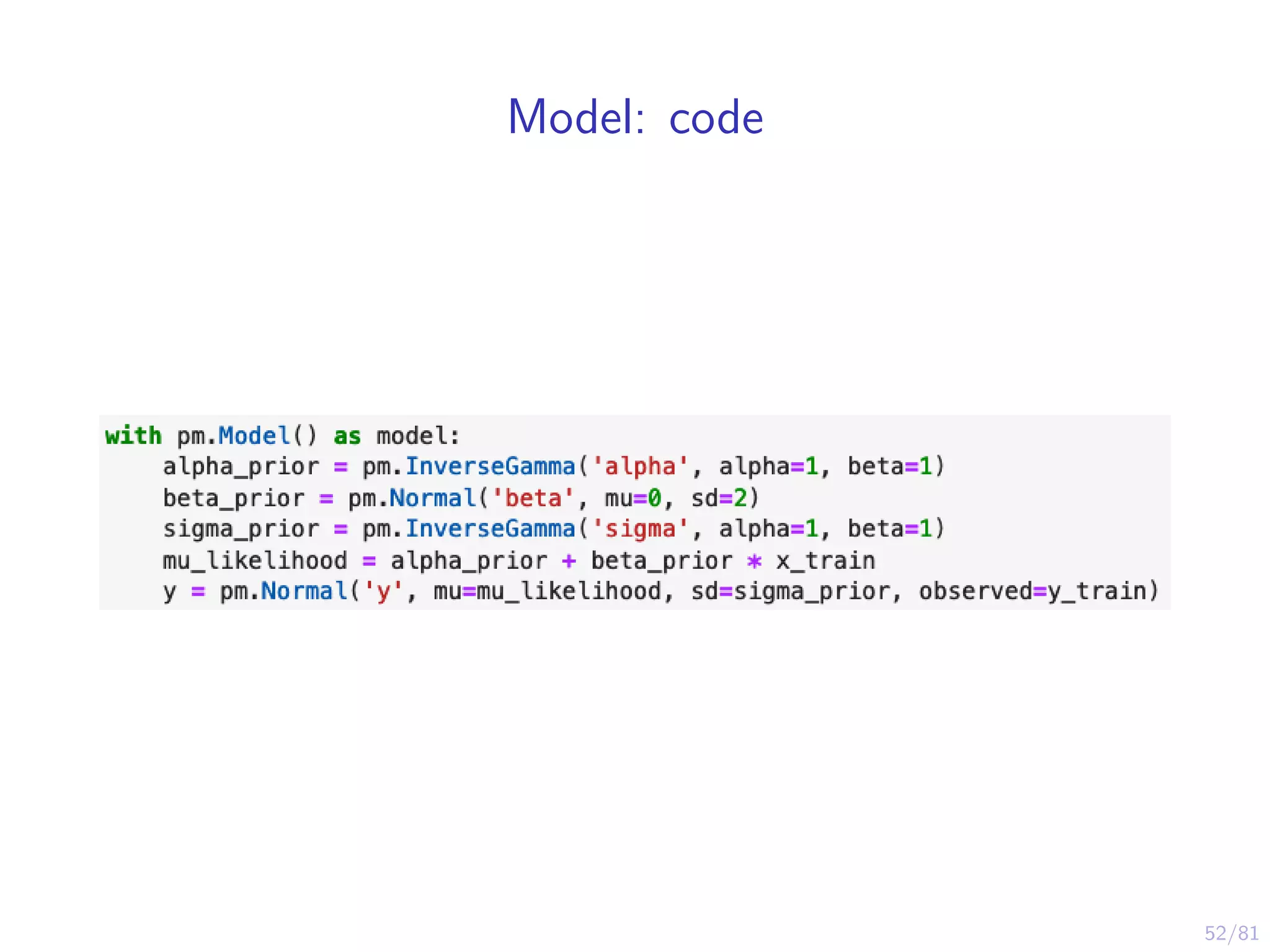

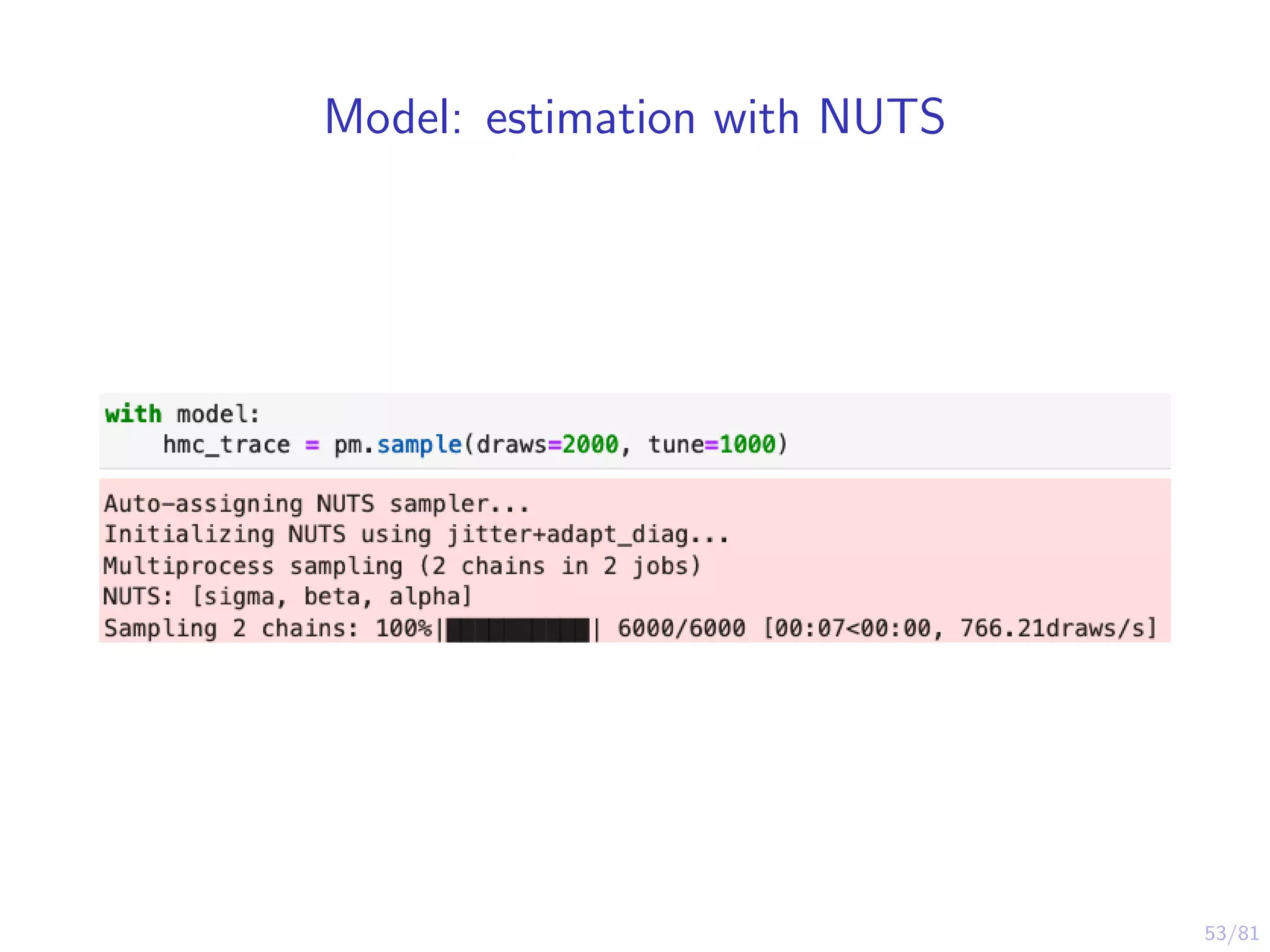

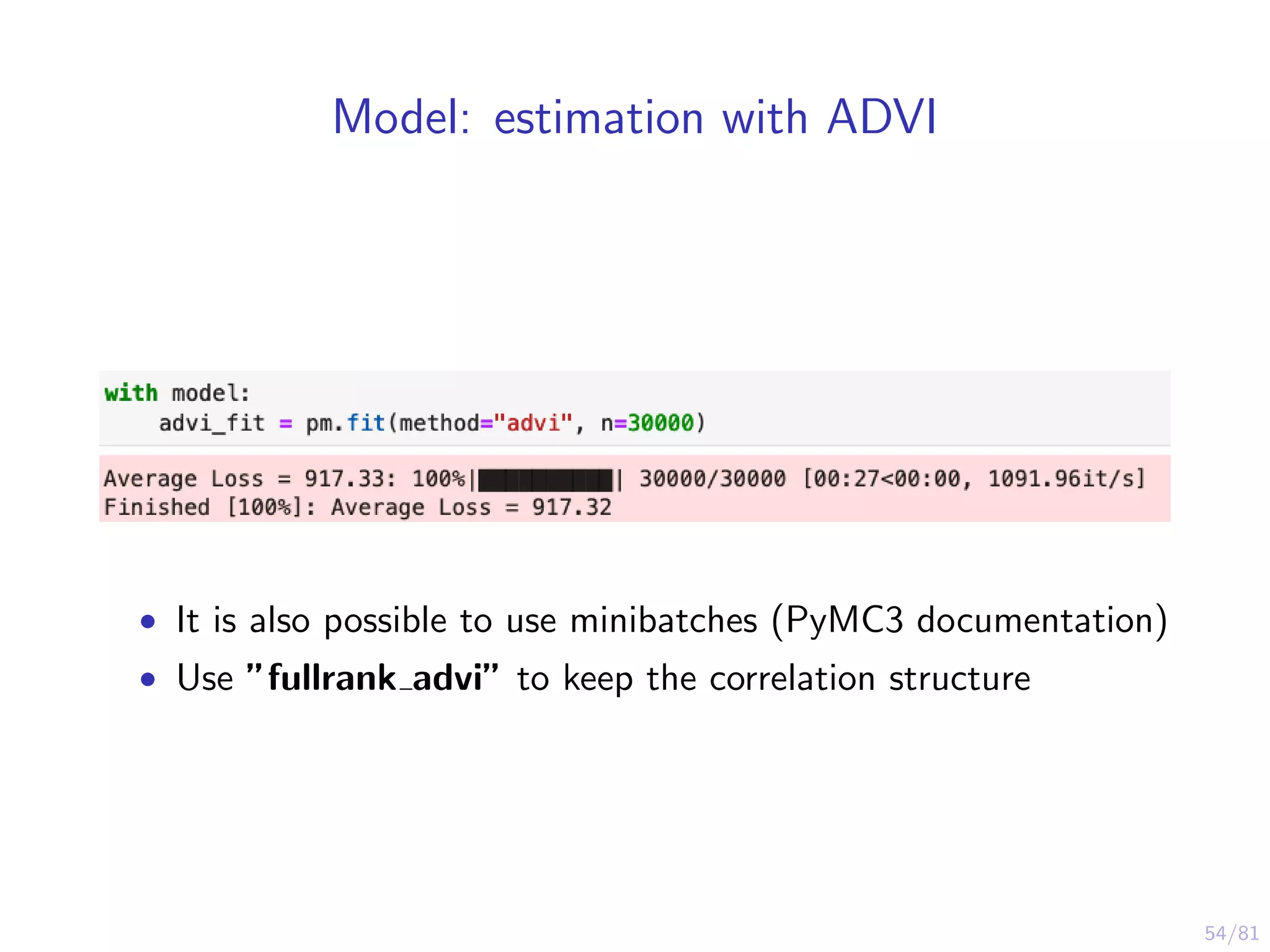

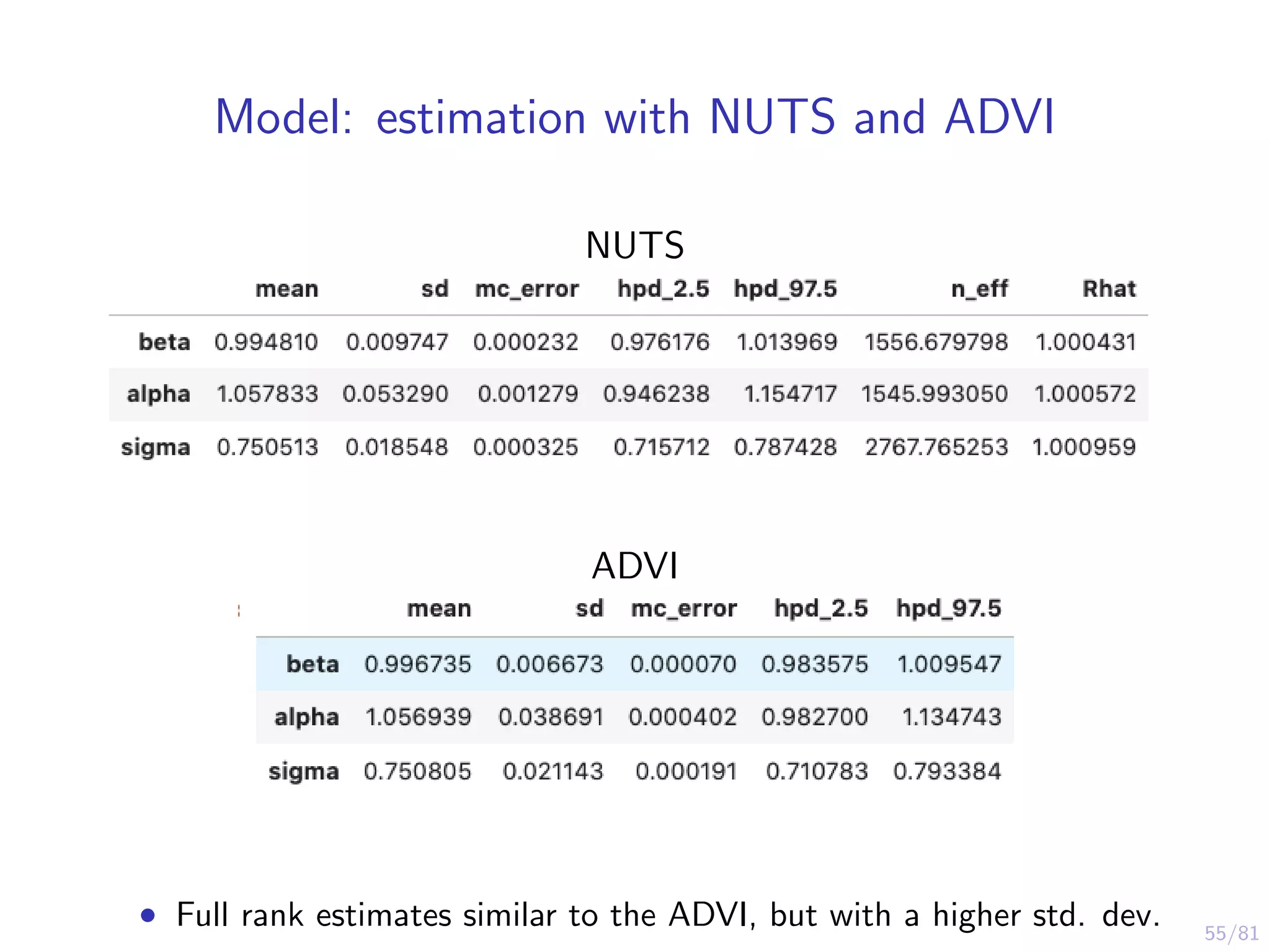

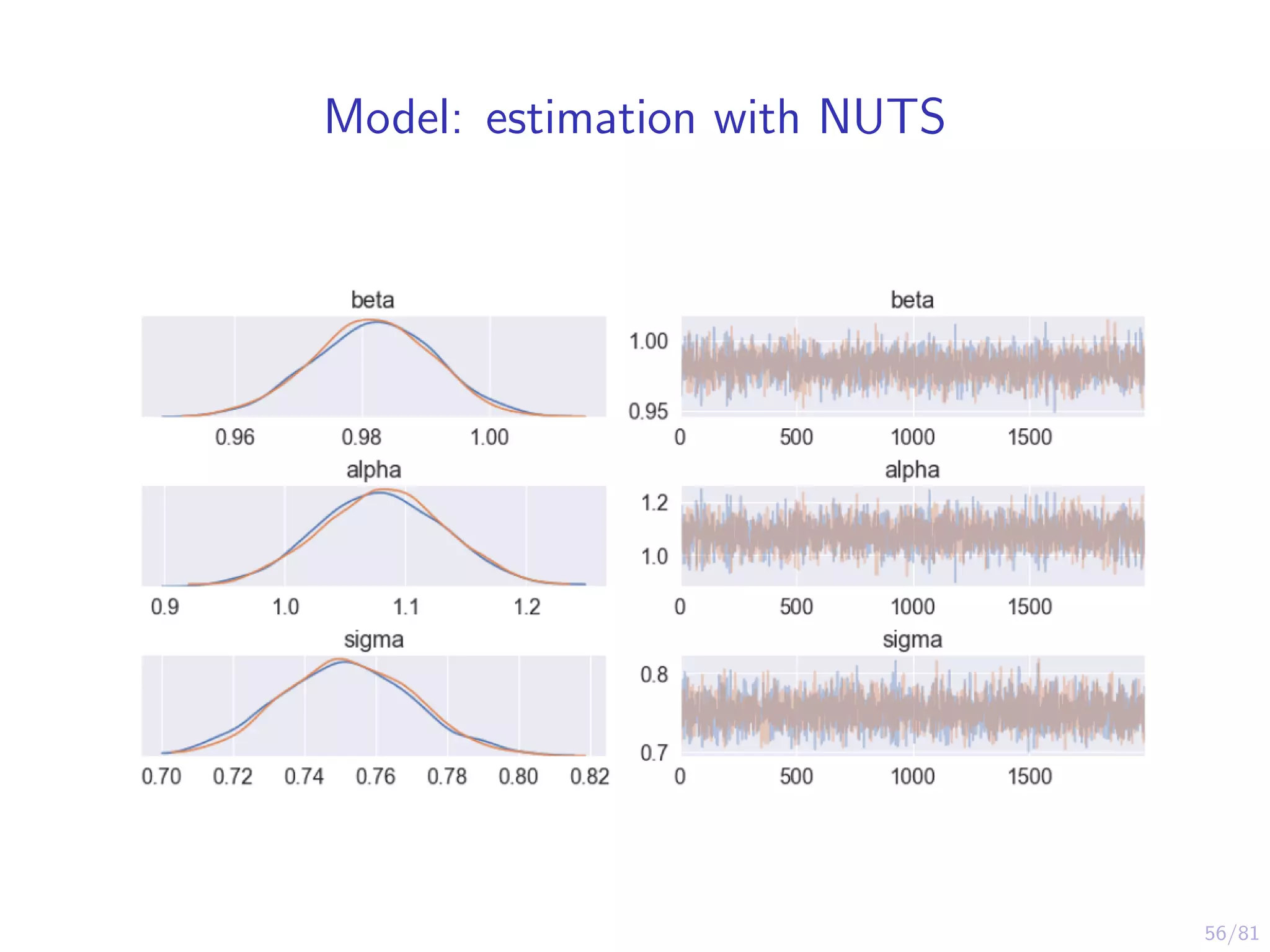

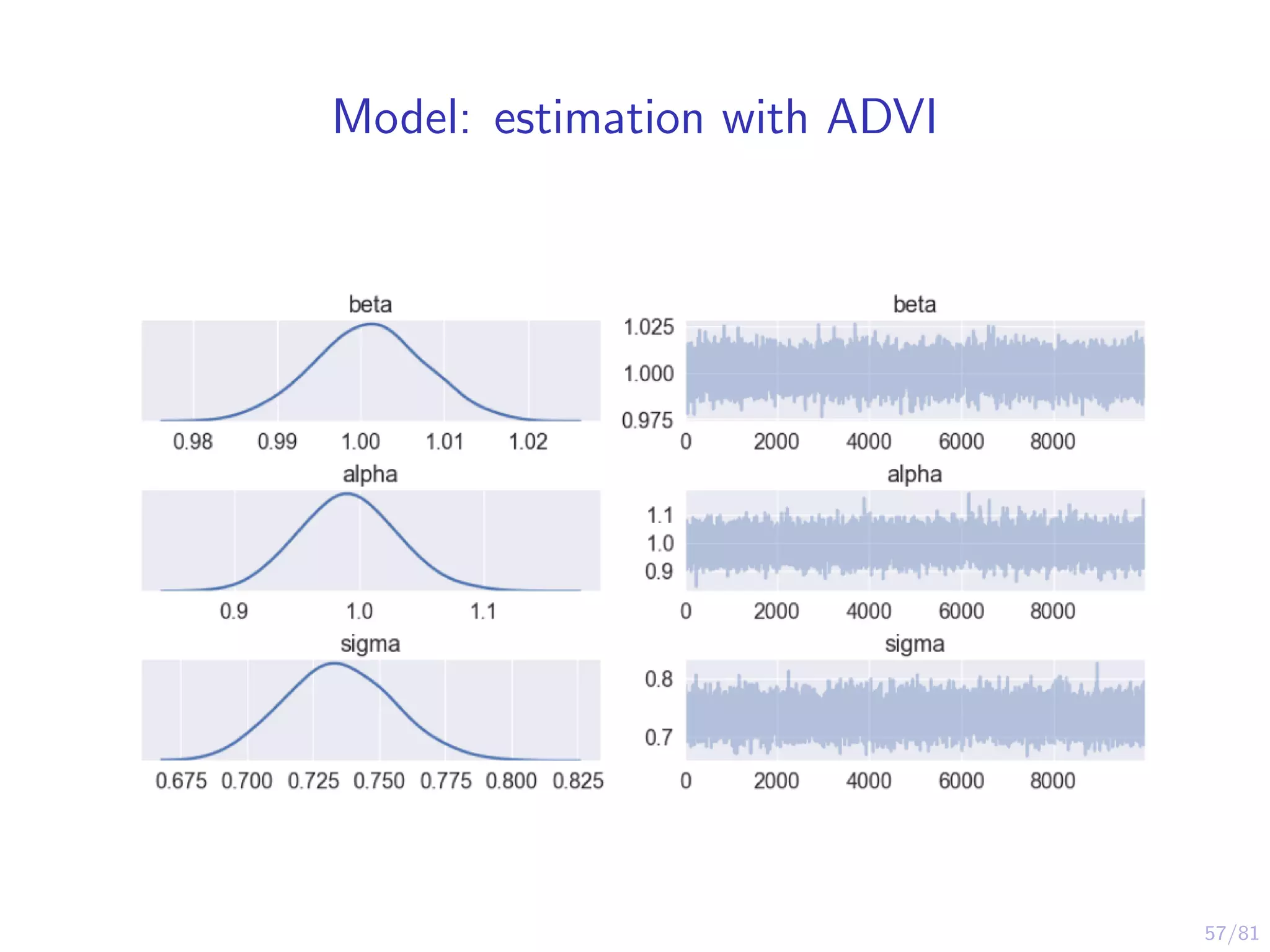

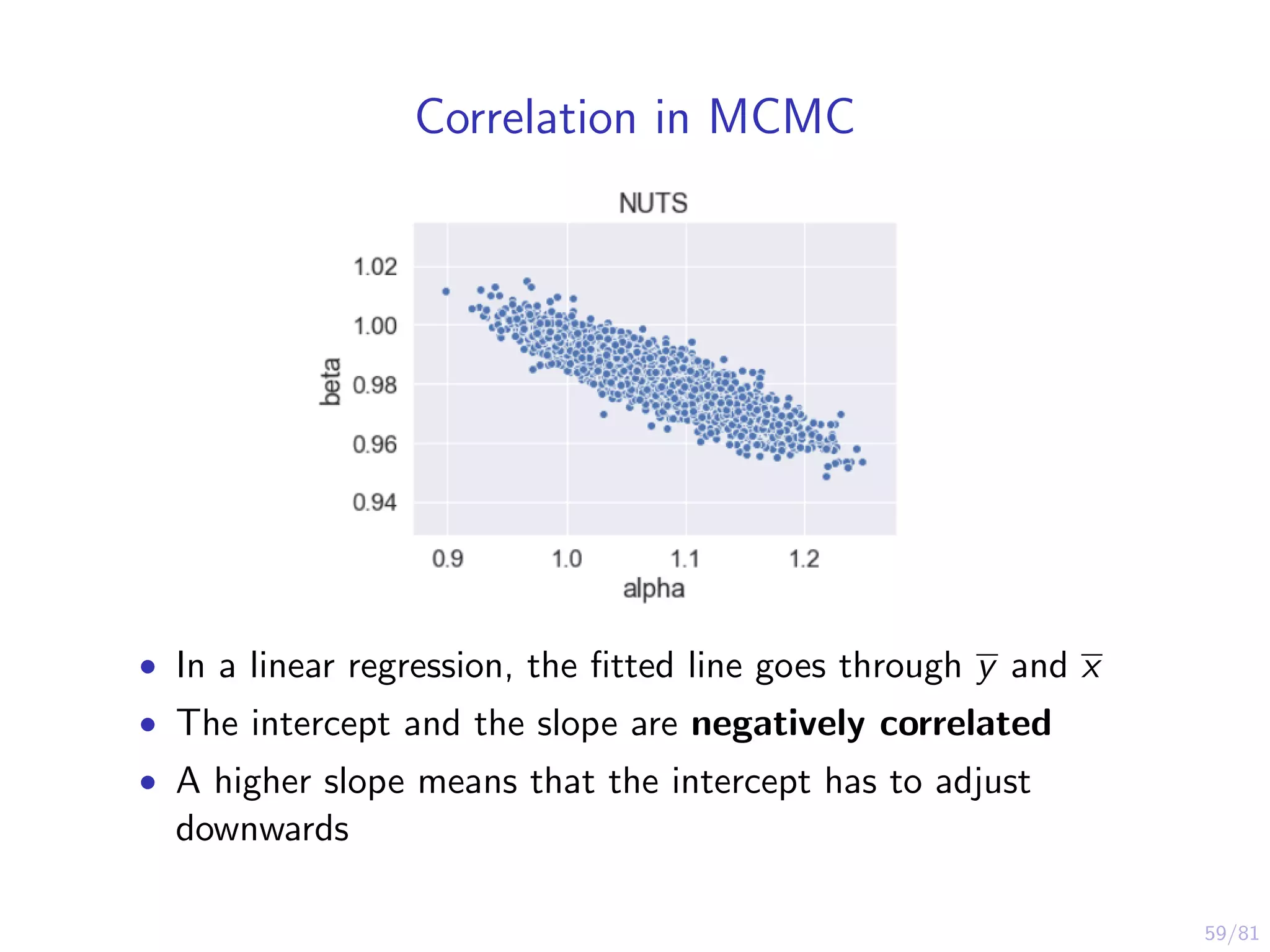

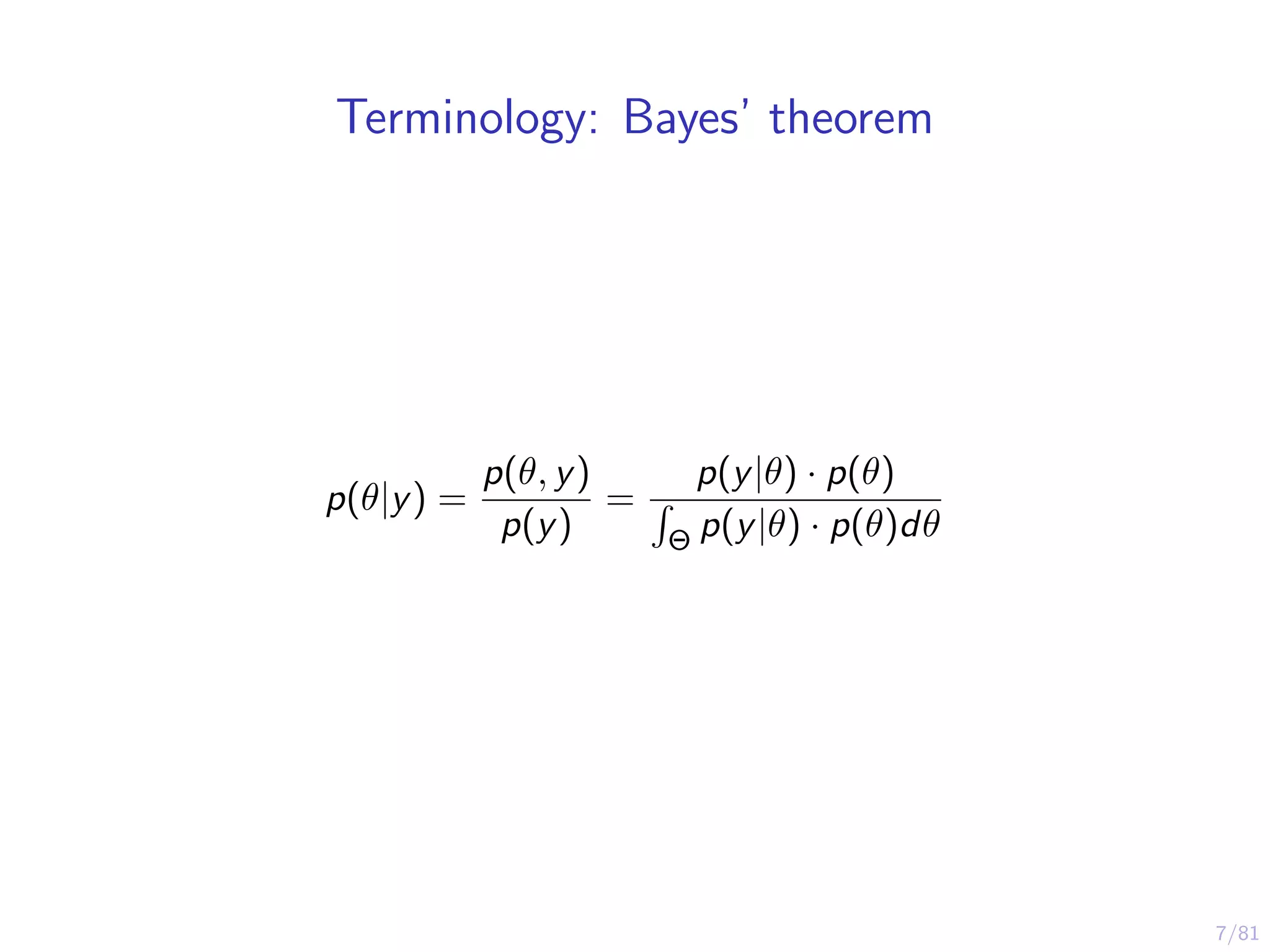

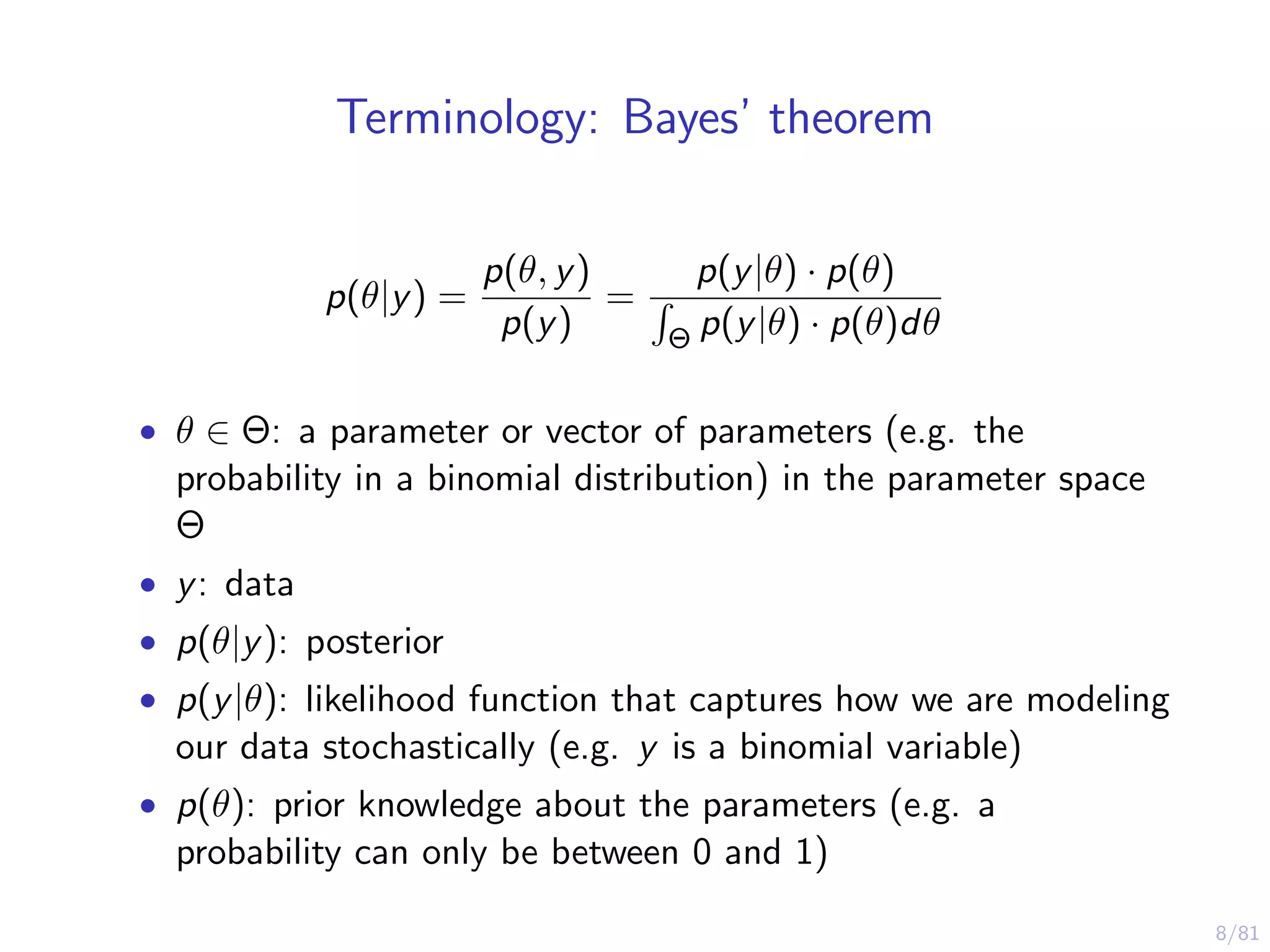

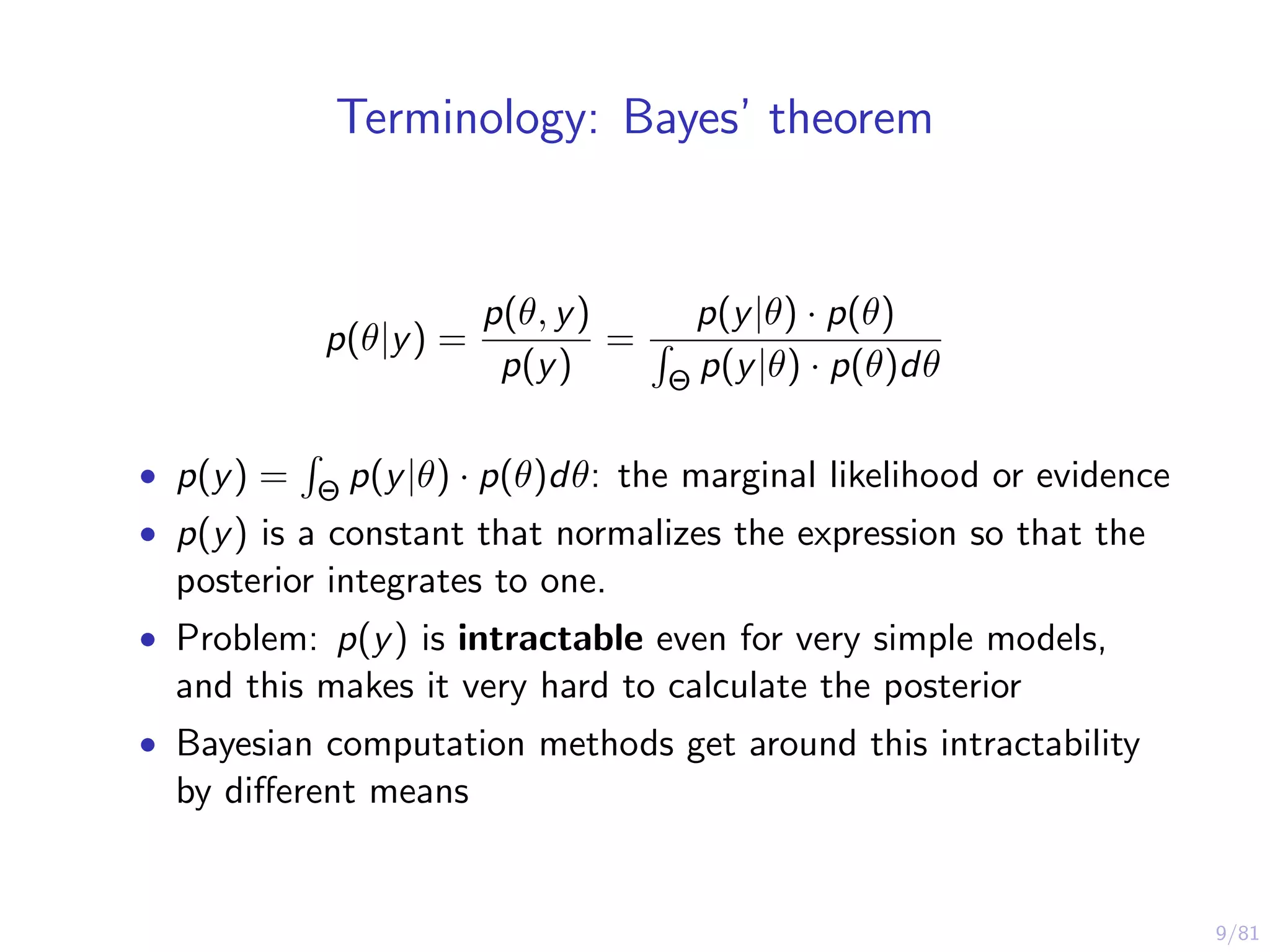

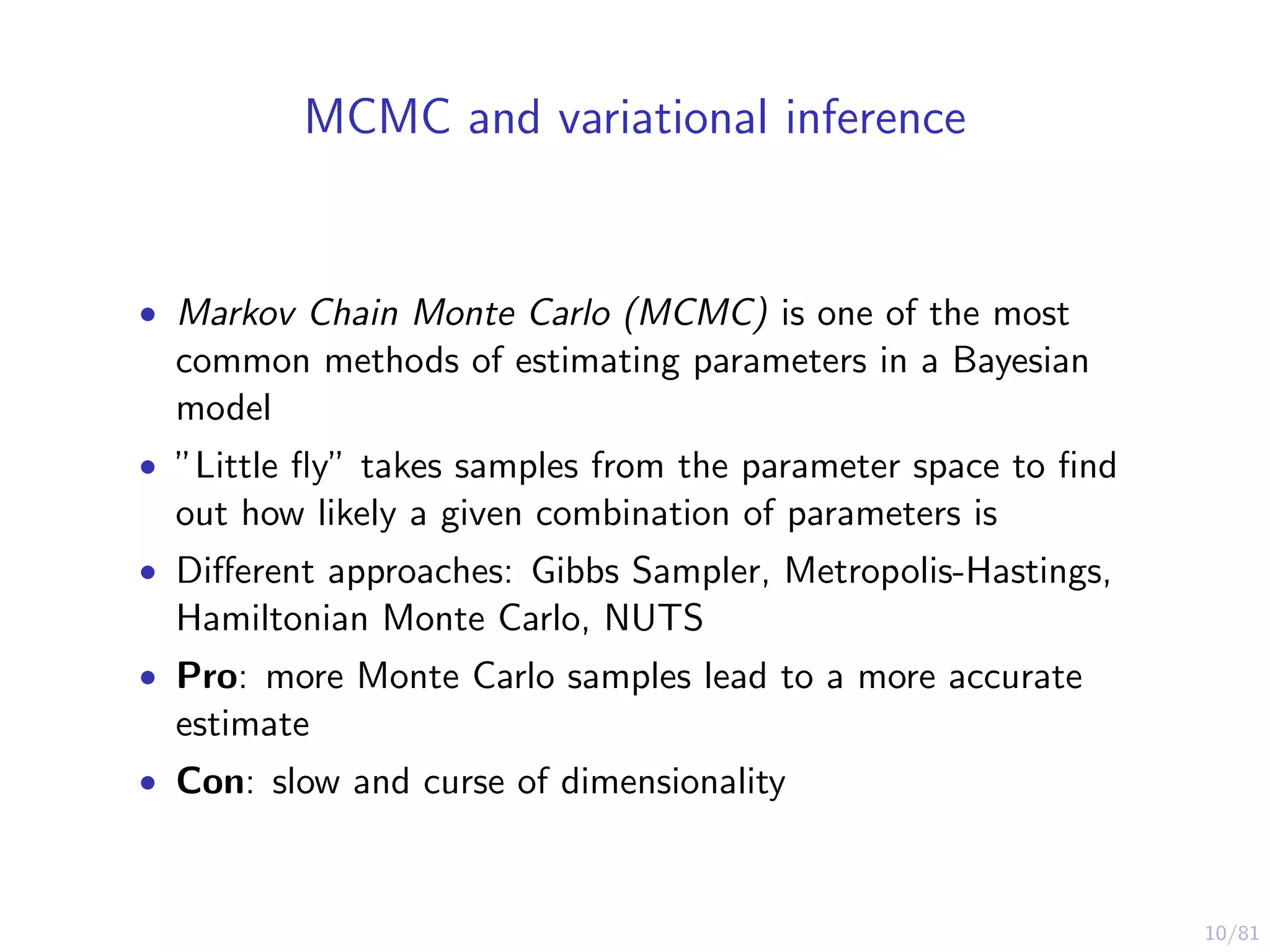

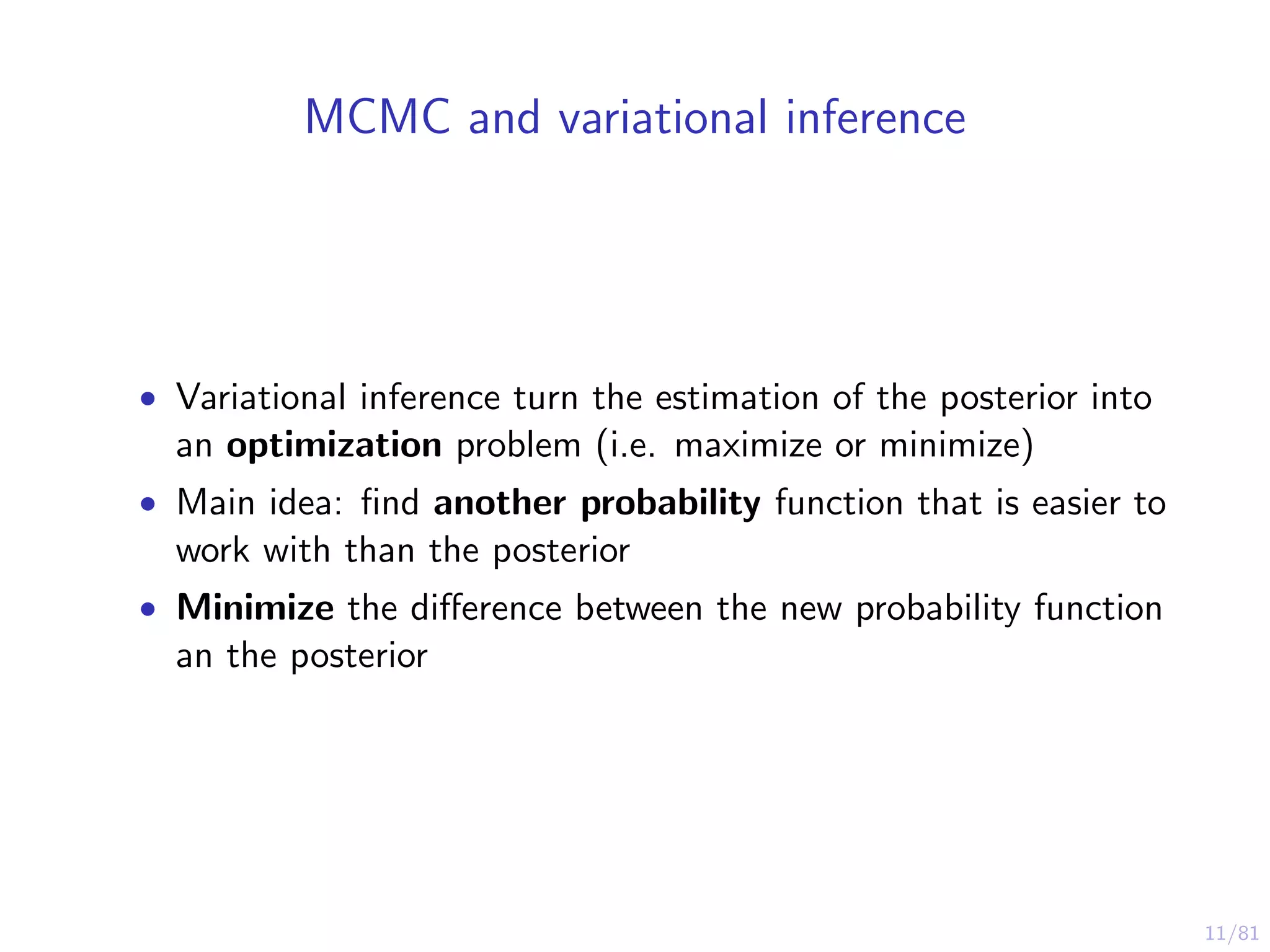

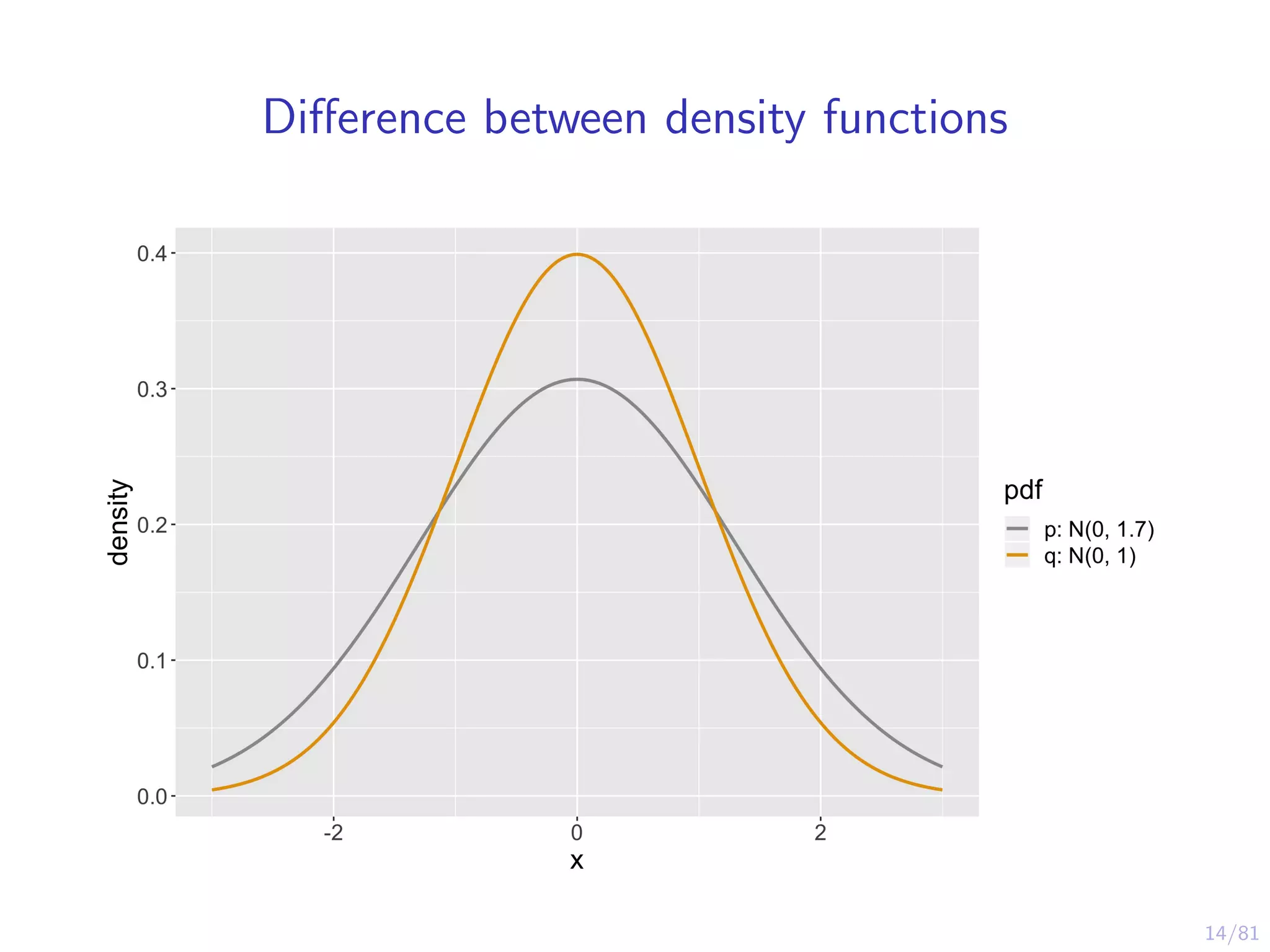

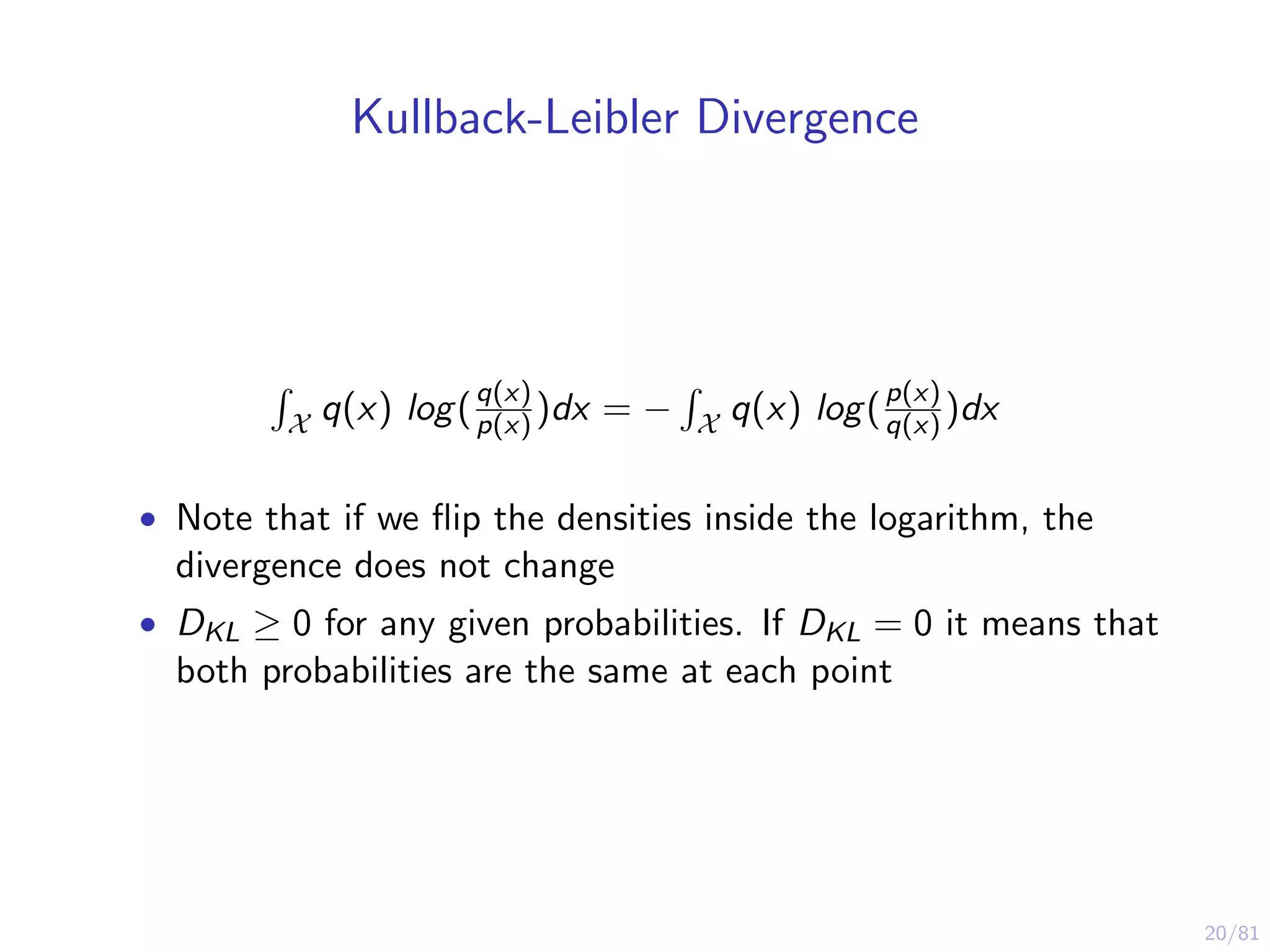

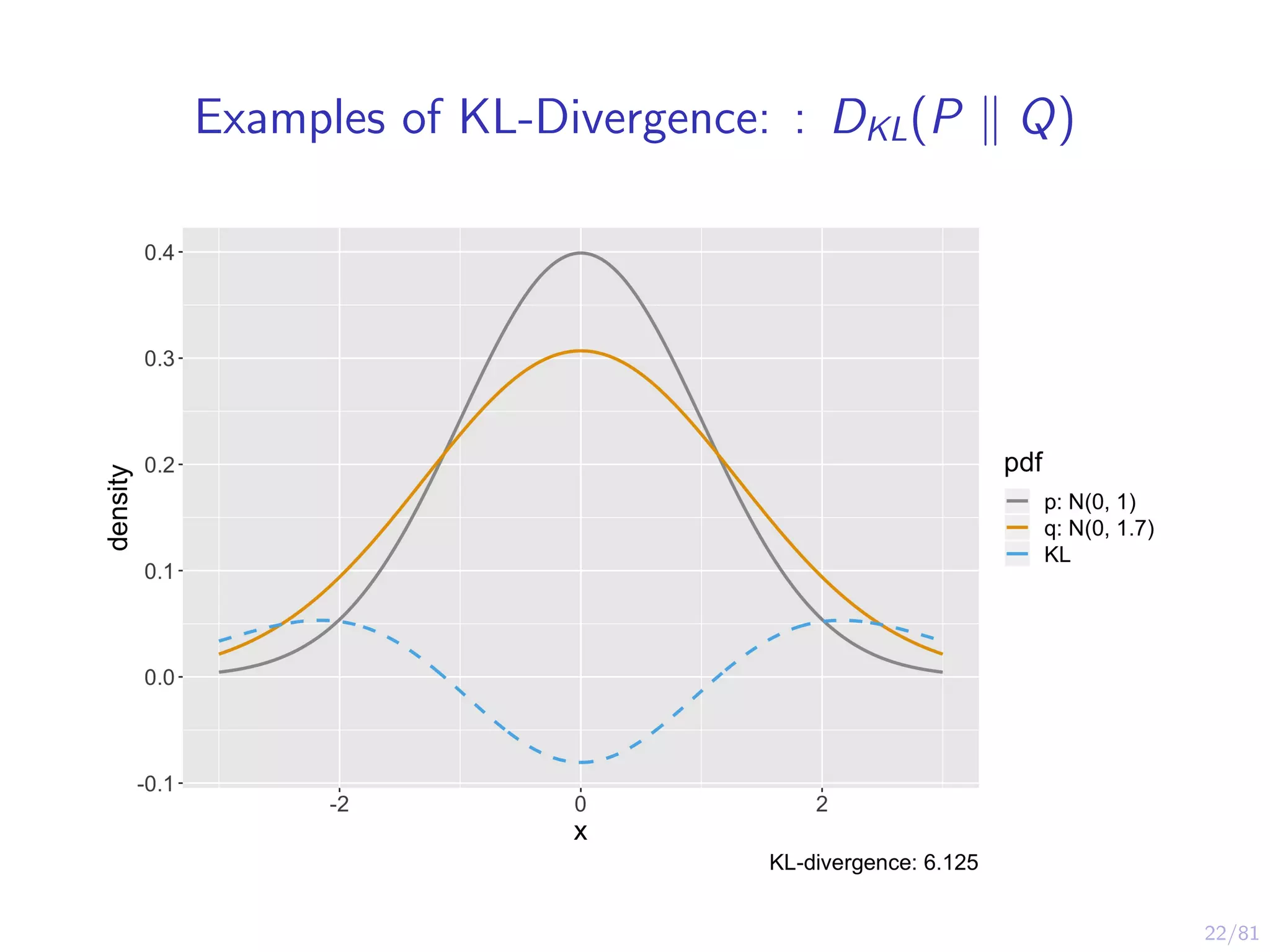

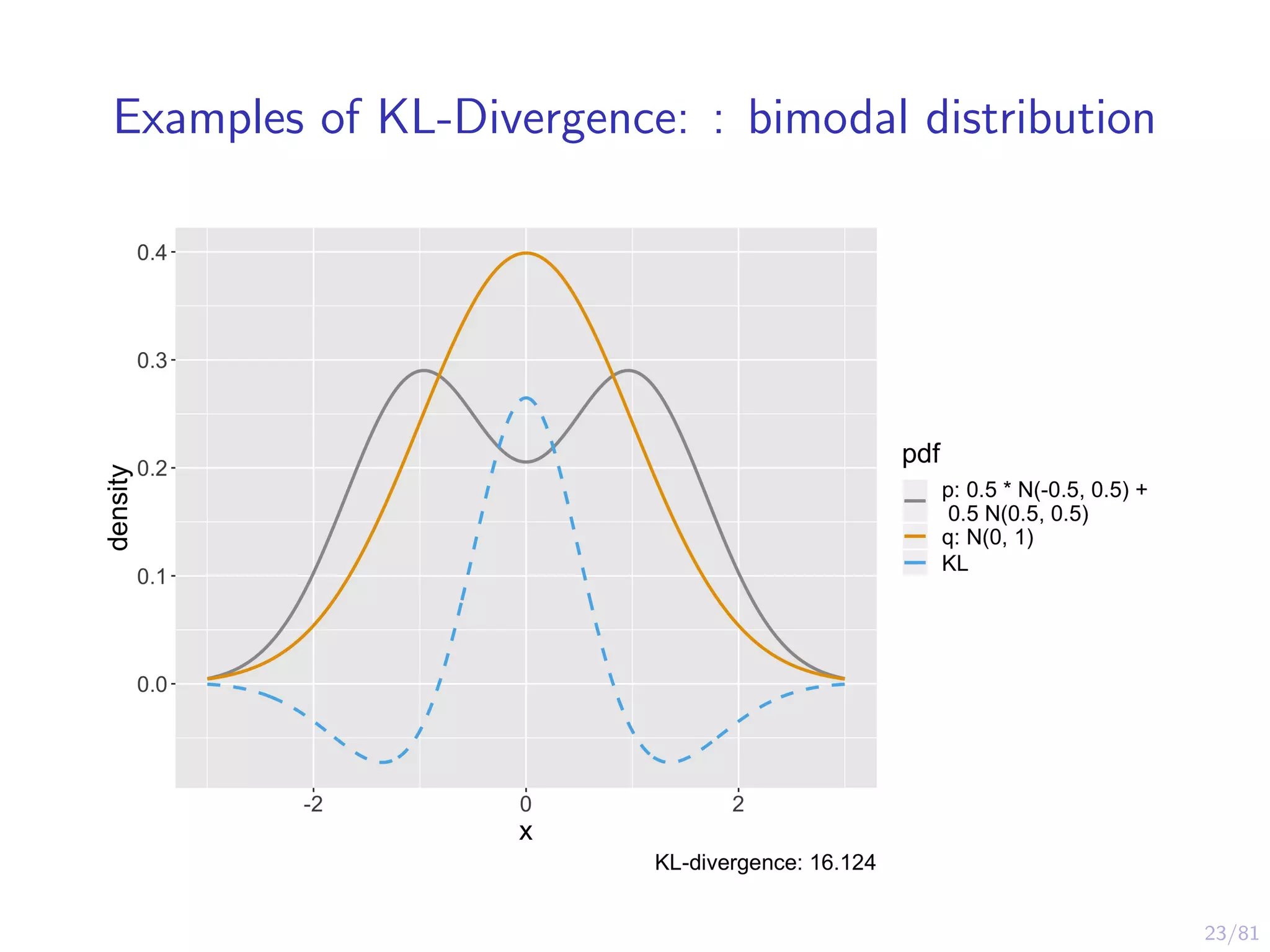

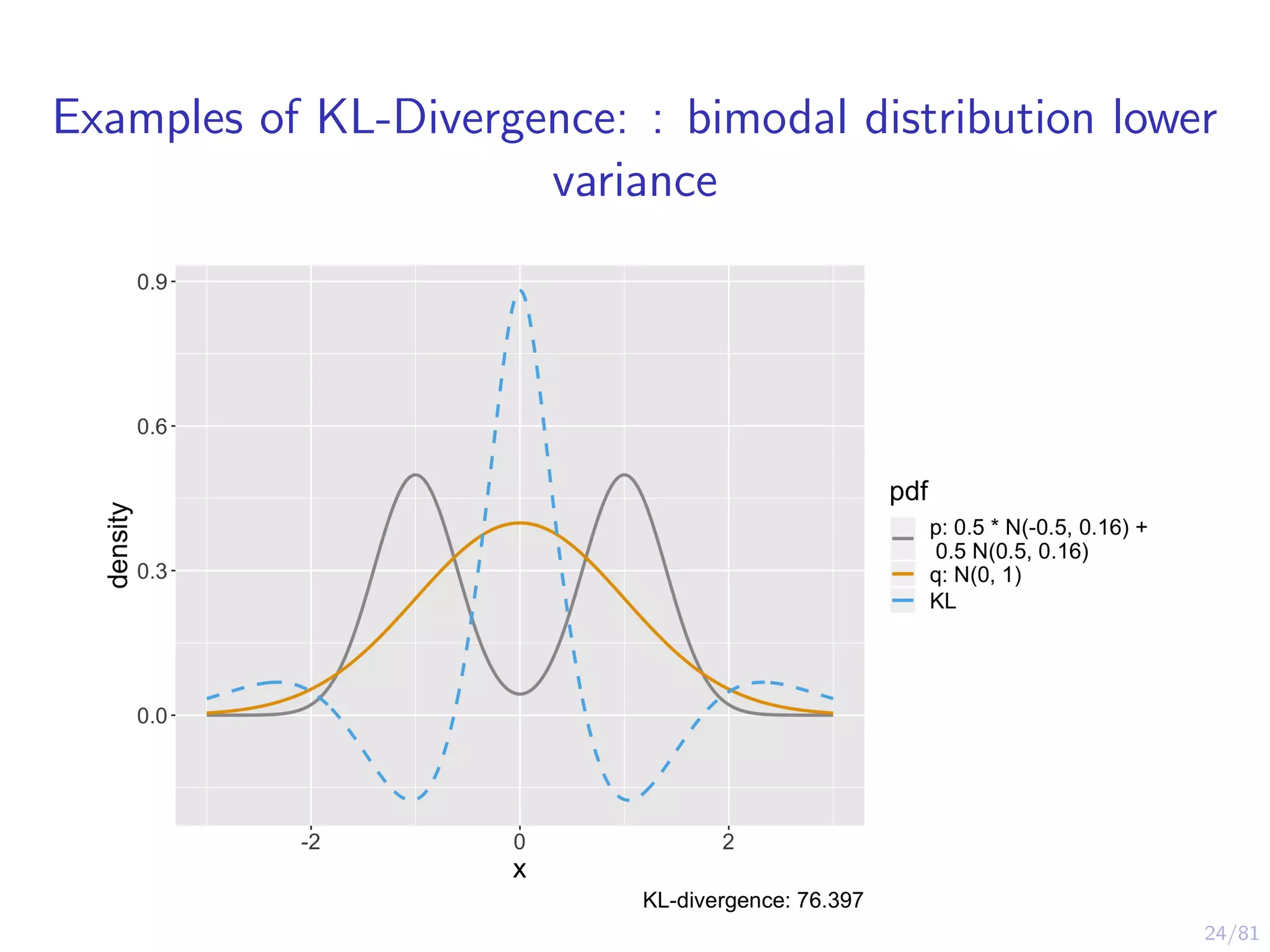

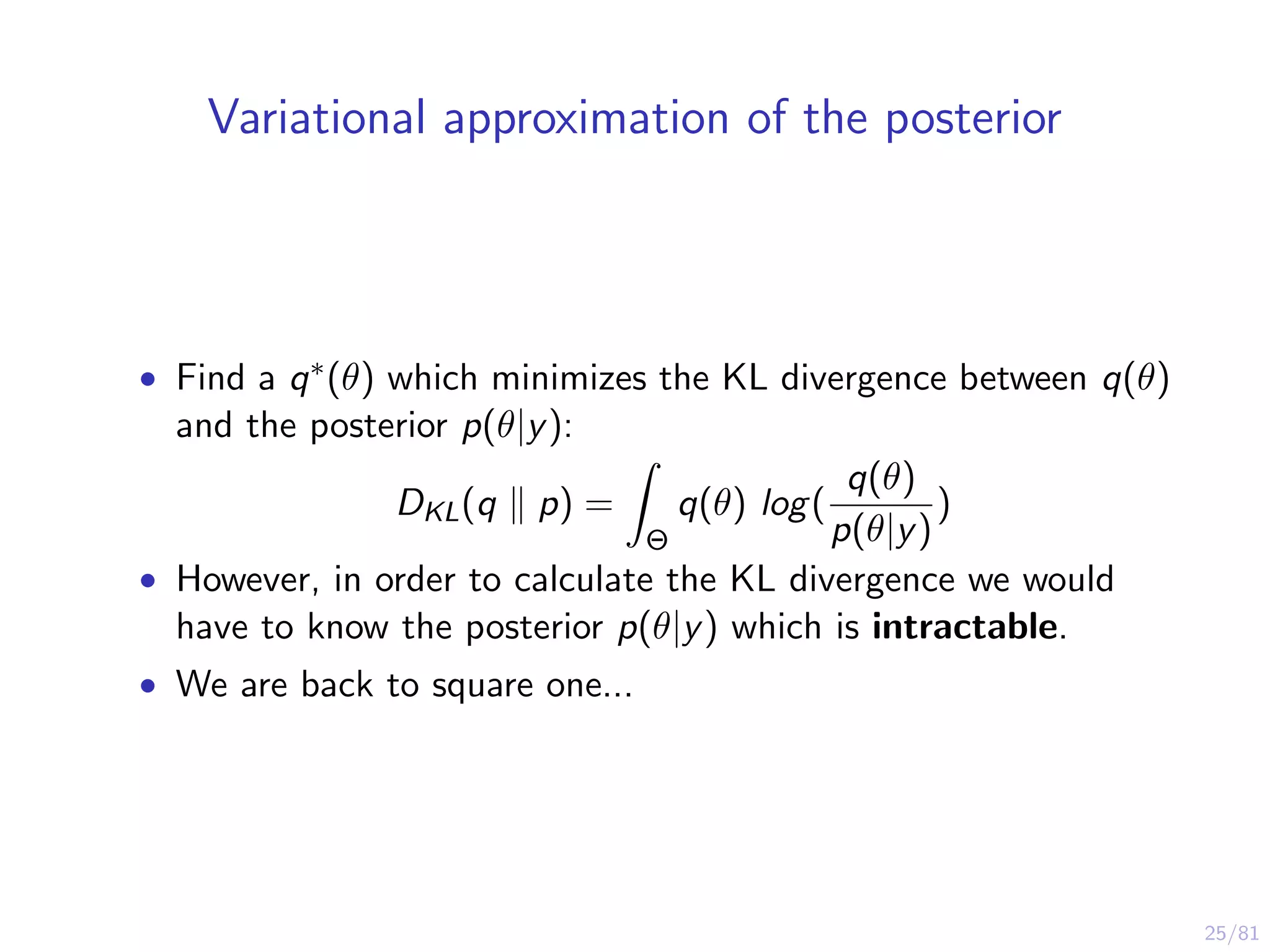

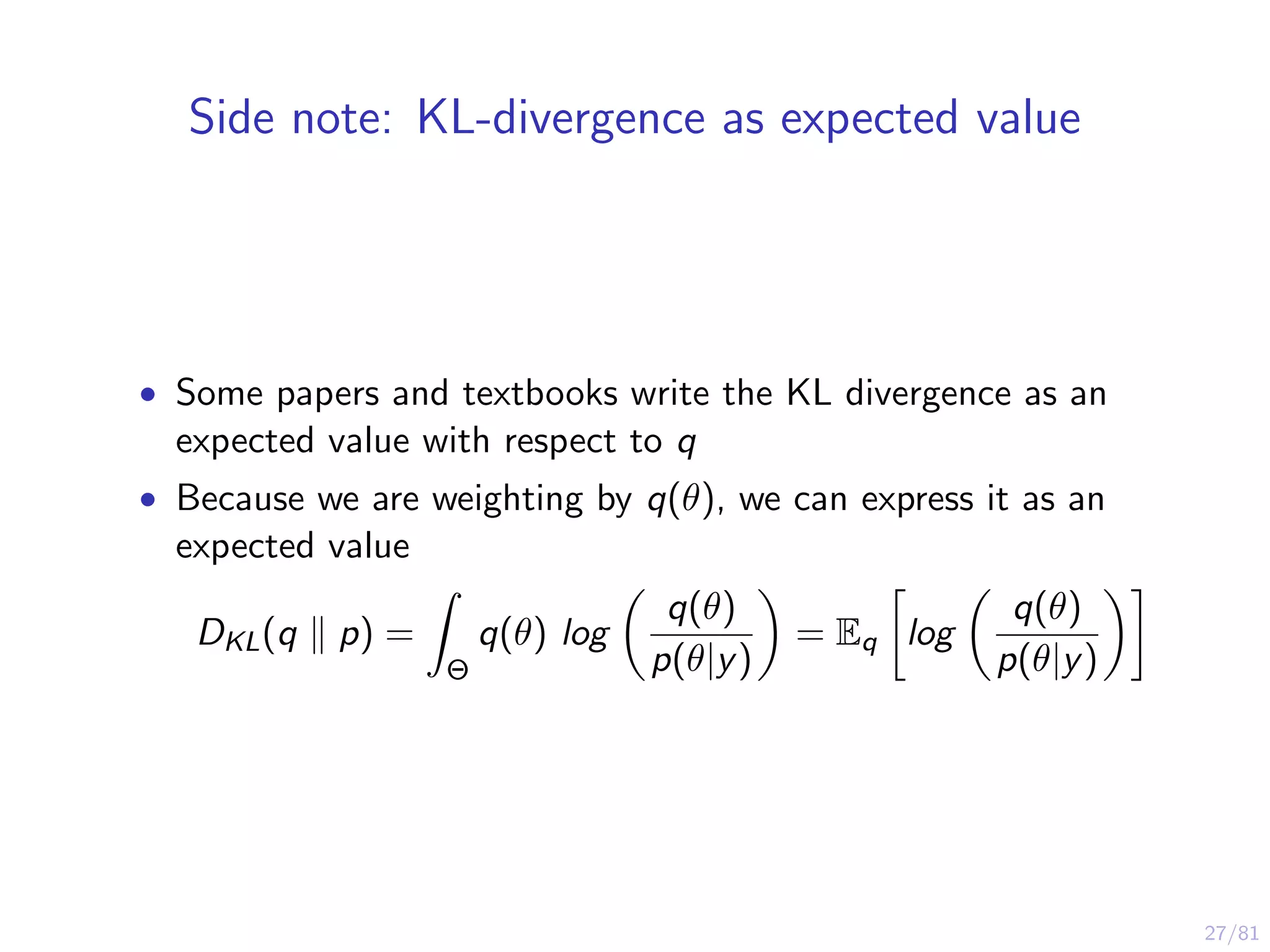

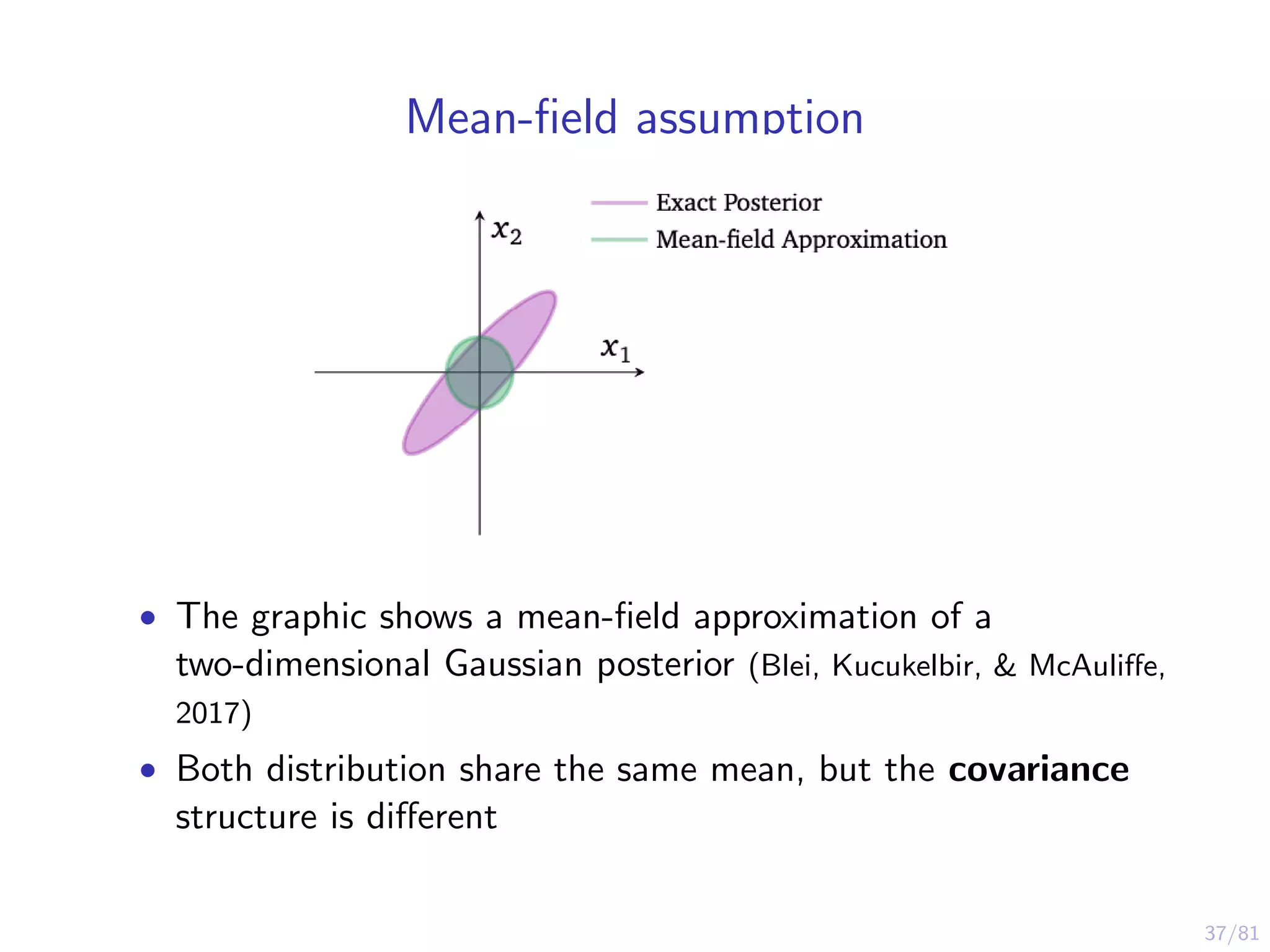

The document provides an introduction to Variational Bayes, outlining the fundamental concepts such as Bayesian inference, Kullback-Leibler divergence, and optimization strategies like Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO). It contrasts Variational Inference with traditional MCMC methods, emphasizing the speed advantages of the former while noting trade-offs in precision and understanding. Examples and algorithms are discussed, including implementations with libraries like PyMC3, aimed at making Bayesian computation more accessible.

![46/81

Black box variational inference: how does it work?

• Noisy gradient of the ELBO, λ is a hyperparameter (Ranganath,

Gerrish, & Blei, 2014):

λL = Eq[( λlog q(θ|λ))(log p(y, θ) − log q(θ|λ))]

• q(θ|λ) is from the variational families and can be stored in a

library

• p(y, θ) = p(θ)p(y|θ) is equivalent to writing down the model

• Black box criteria:

• Sample from q(θ|λ) (Monte Carlo)

• Evaluate λlog q(θ|λ)

• Evaluate log p(y, θ)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viintroduction-191203163142/75/Variational-Bayes-A-Gentle-Introduction-46-2048.jpg)