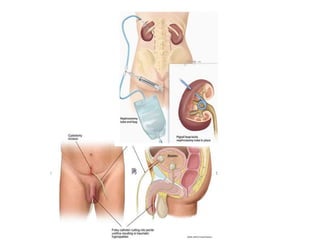

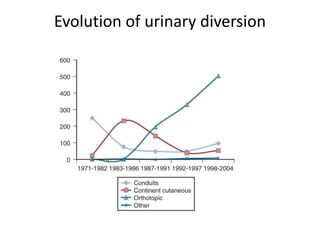

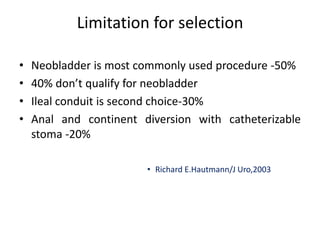

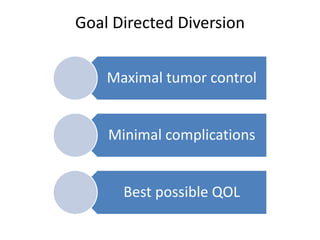

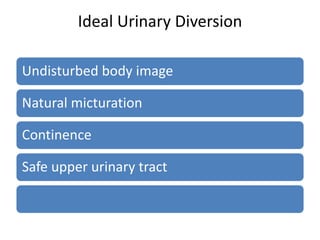

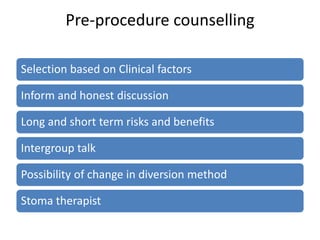

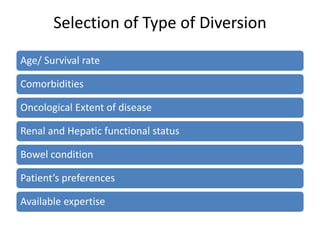

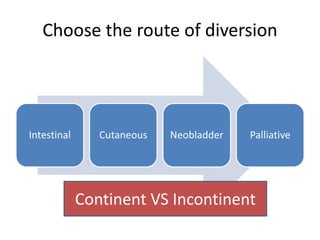

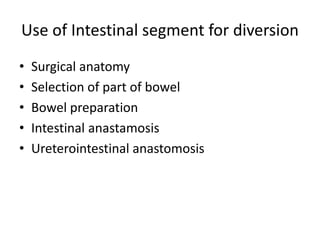

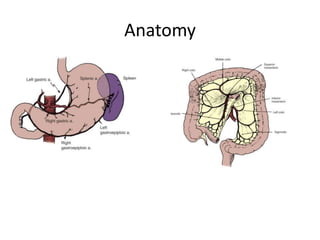

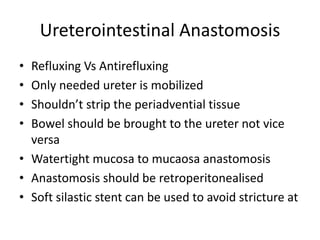

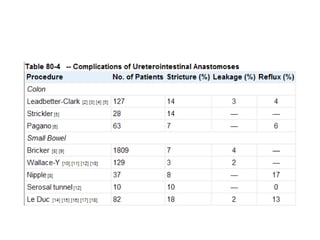

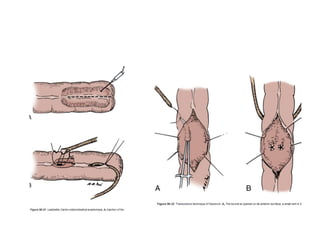

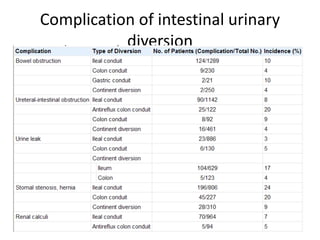

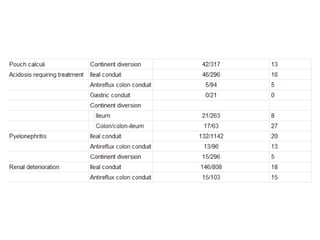

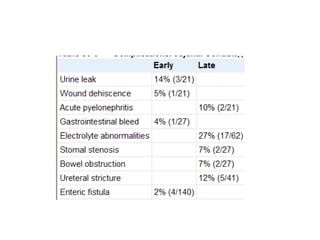

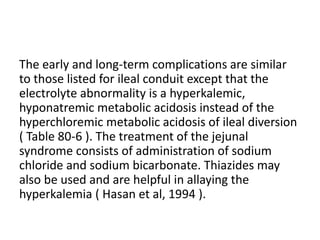

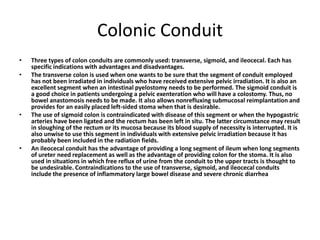

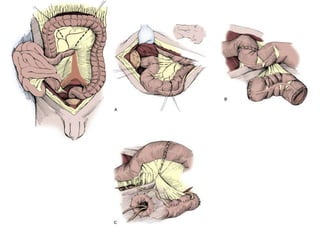

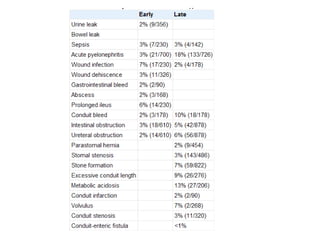

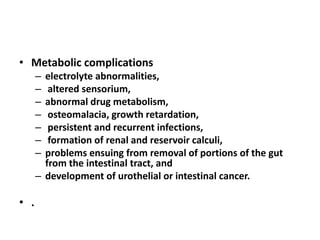

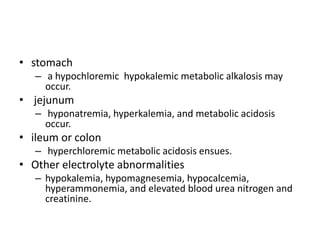

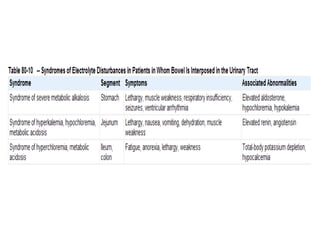

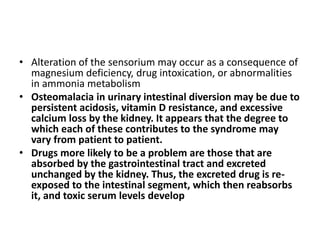

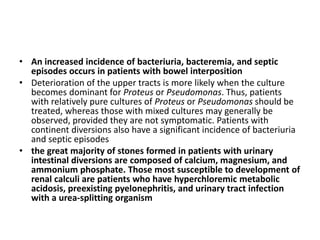

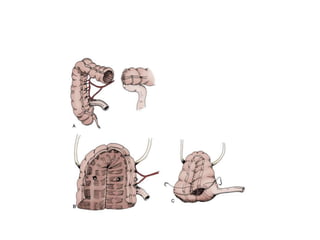

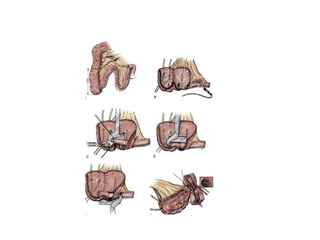

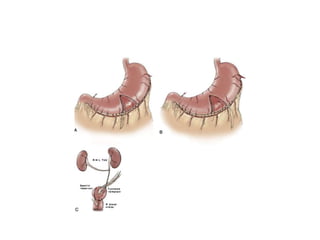

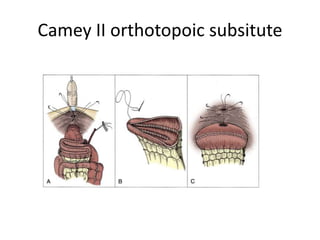

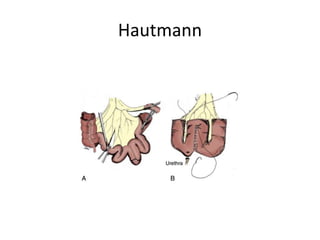

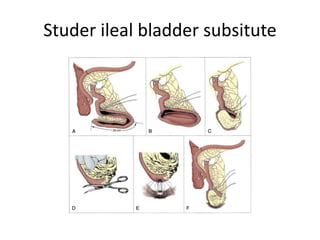

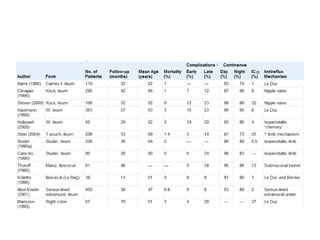

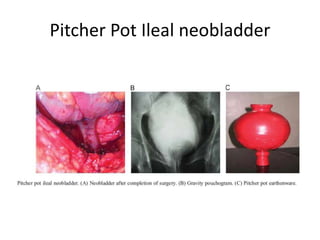

This document provides an overview of urinary diversion and urinary bladder substitution techniques. It discusses the history and types of urinary diversion, including temporary vs. permanent, external vs. internal, continent vs. incontinent, and definitive vs. palliative diversions. Common techniques described include ileal conduits, colonic conduits, cutaneous continent diversions like Kock pouches, and orthotopic neobladders. Complications of different diversion methods are outlined. Factors in selecting the appropriate diversion type include the patient's age, comorbidities, renal function, and tumor extent/location. The goal is to maximize tumor control while minimizing complications and optimizing quality of life.