Types of communication, inter process

communication,

multicast

communication,

message-oriented

communication, MPI, network virtualization, overlay networks

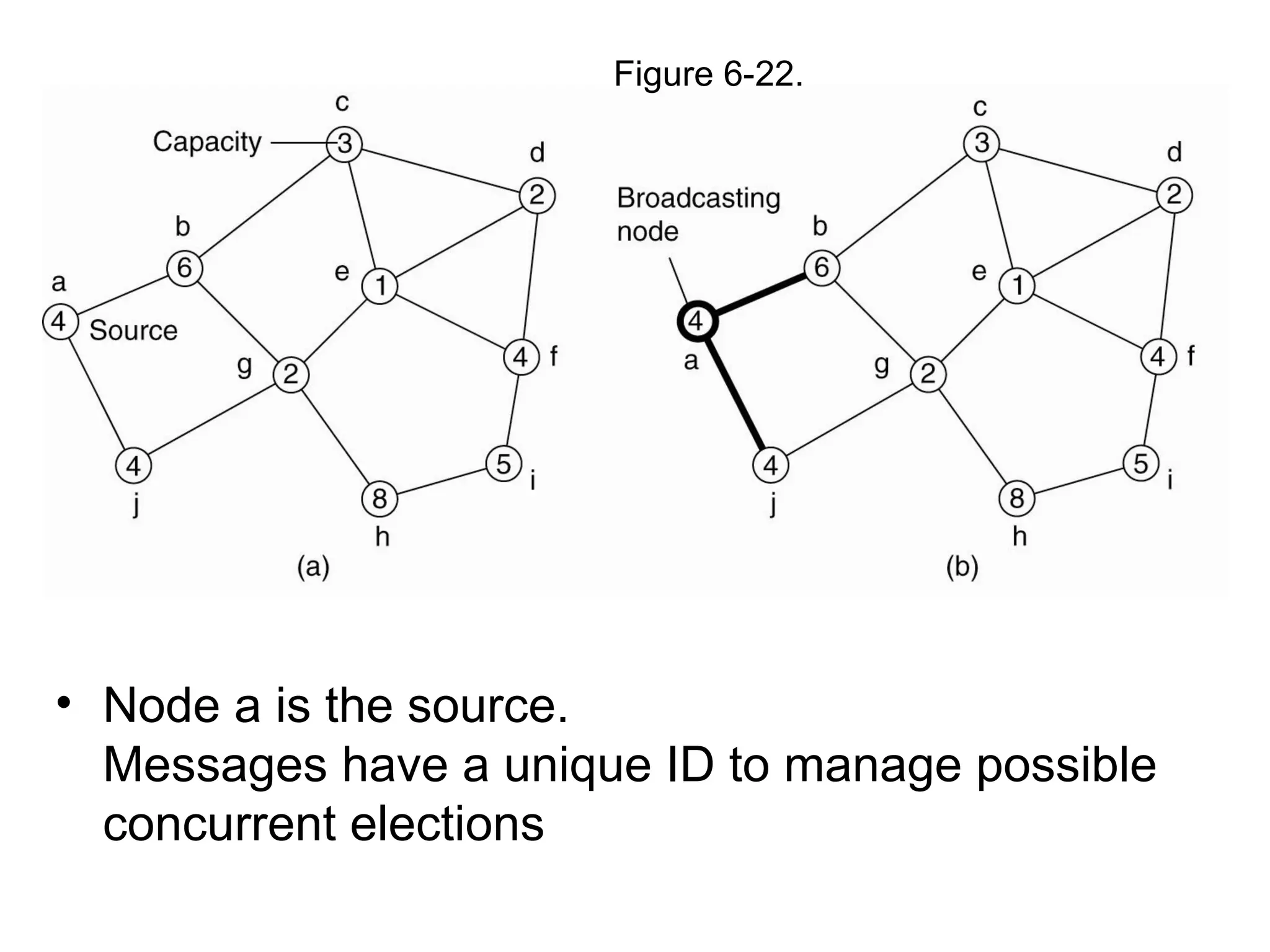

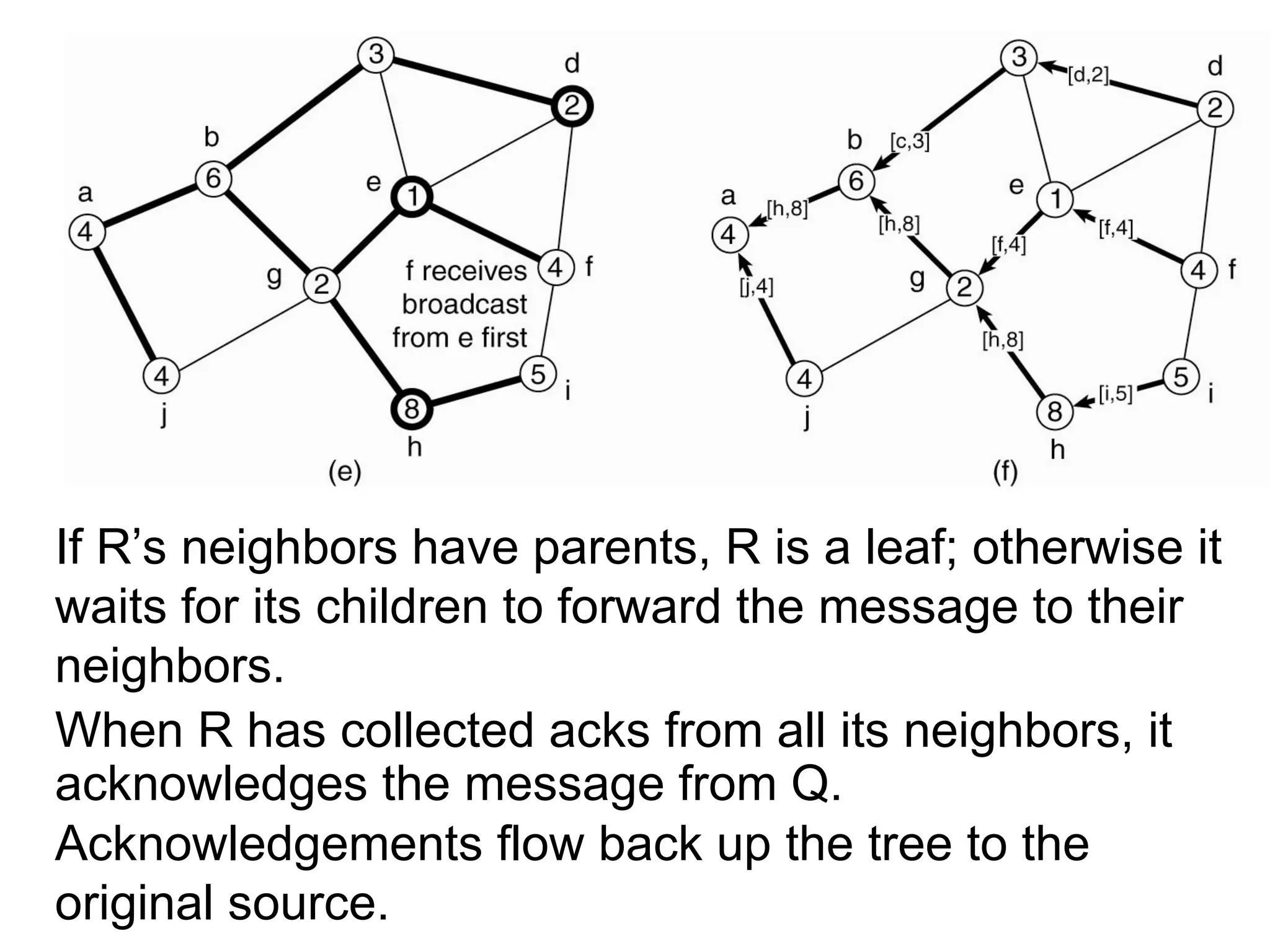

Coordination: Clock synchronization, logical clocks, mutual

exclusion, election algorithms, Gossip based coordination.

Case Study: IBM WebSphere Message Queuin

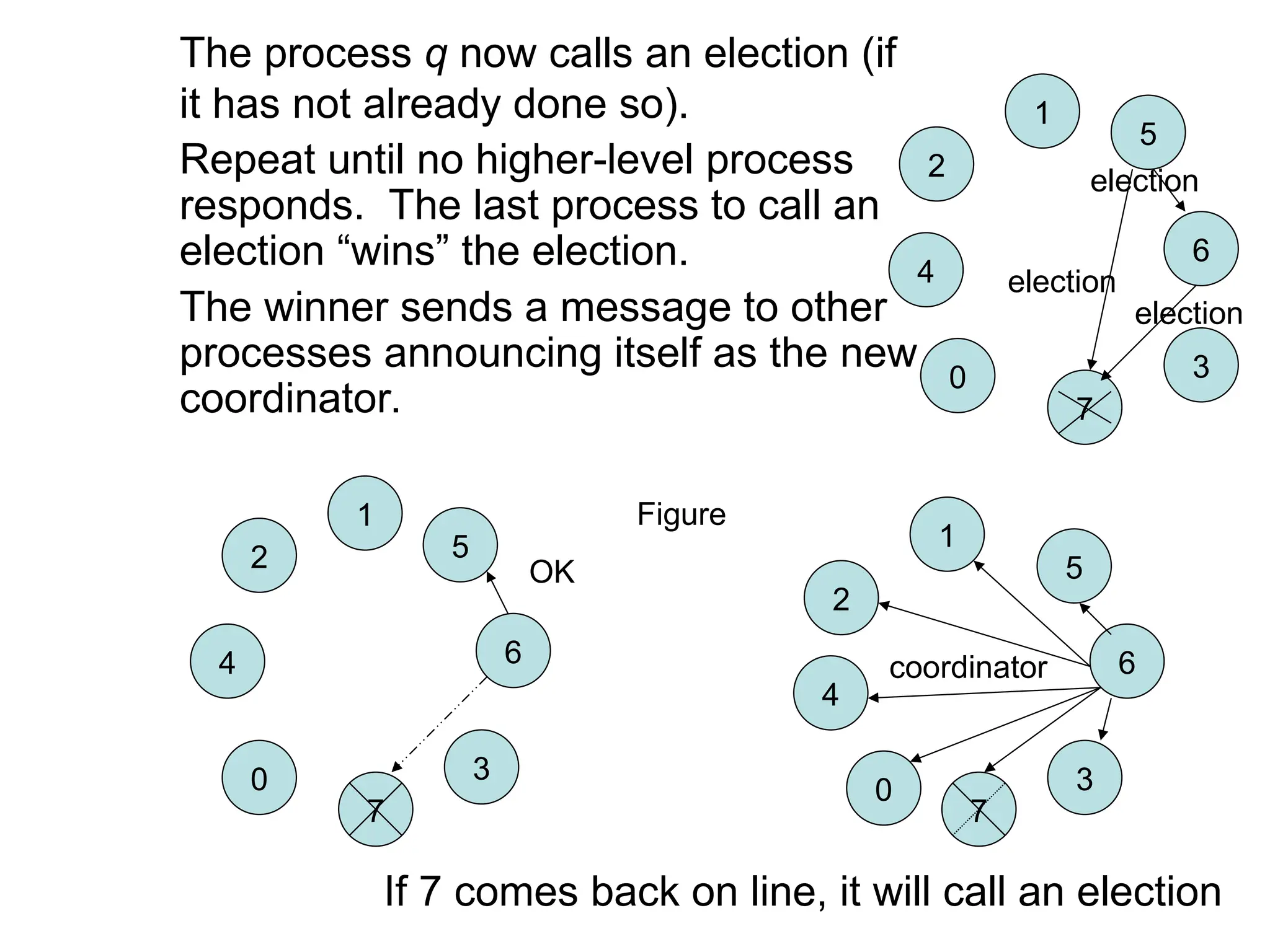

![Ring Algorithm - Details

• When the message returns to p, it sees its own

process ID in the list and knows that the circuit is

complete.

• P circulates a COORDINATOR

message with the new high

number.

• Here, both 2 and 5

elect 6:

[5,6,0,1,2,3,4]

[2,3,4,5,6,0,1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elections-250823085932-6e4c8cff/75/Unit_2_Communication-and-Coordination_Elections-ppt-14-2048.jpg)