This document provides an introduction to nuclear physics and radioactivity. It discusses:

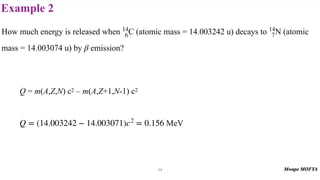

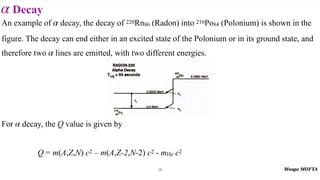

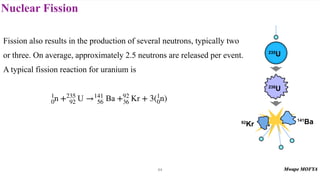

1) The discovery of radioactivity and the nucleus. Rutherford's scattering experiment in 1911 revealed the existence of the nucleus as the source of radioactivity.

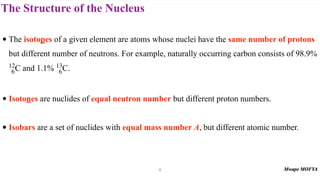

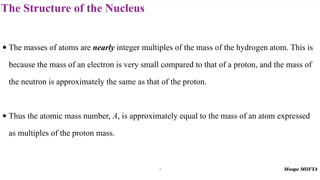

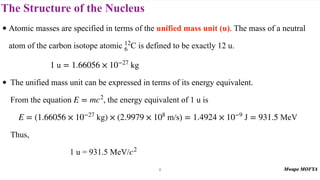

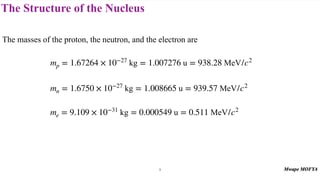

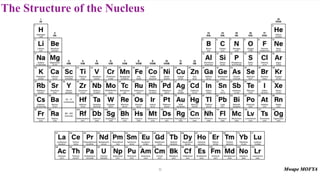

2) The structure of the nucleus, including its composition of protons and neutrons (nucleons), atomic number, mass number, isotopes, and typical size.

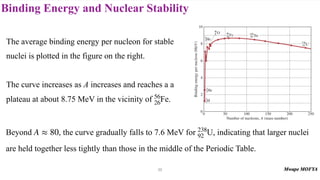

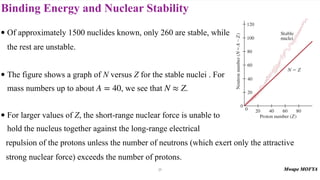

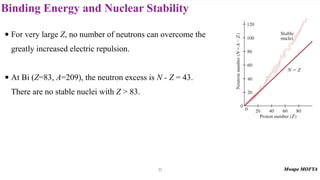

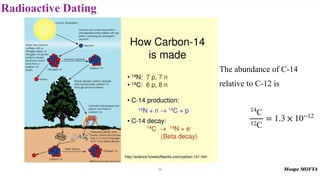

3) Nuclear stability and binding energy. The strong nuclear force holds nuclei together, and nuclei with intermediate mass numbers have the highest binding energy per nucleon. Only certain combinations of protons and neutrons produce stable nuclei.

![Binding Energy and Nuclear Stability

• Since it is easier to get the masses of neutral atoms from tables, the binding energy of a

nuclide is can be found from the expression

• The quantities mH and mX are the masses of neutral atoms, because it is these atoms that are

listed in tables and the masses of electrons in ZmH and mX cancel.

A

ZX

BE = [ZmH + Nmn − mX]c2

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit7-221101231854-b9da2178/85/UNIT7-pdf-18-320.jpg)

![Example 1

What is the binding energy of the helium nucleus, ?

BE = 28.3 MeV

The average binding energy per nucleon is BE/A = 28.3 MeV/4 = 7.1 eV

4

2He

BE = [ZmH + Nmn − mX]c2

BE = [(2 × 1.007825) + (2 × 1.008665) − (4.002604)]c2

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit7-221101231854-b9da2178/85/UNIT7-pdf-19-320.jpg)