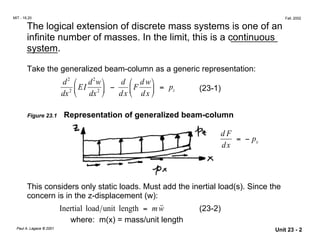

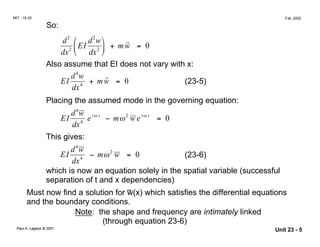

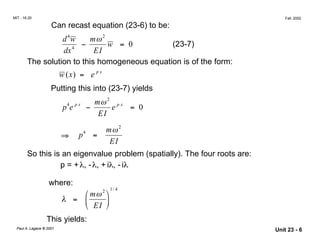

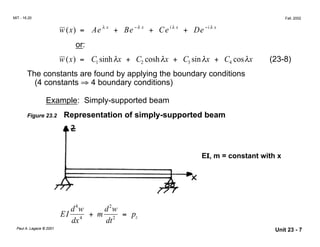

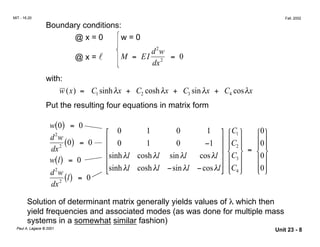

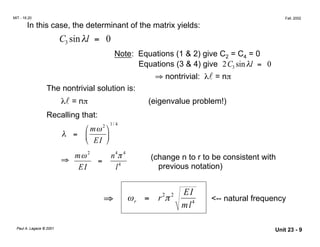

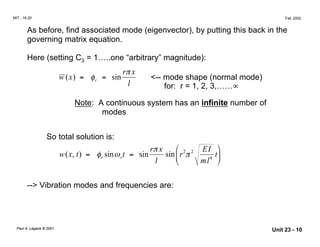

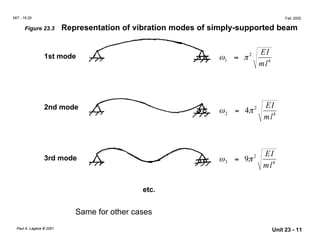

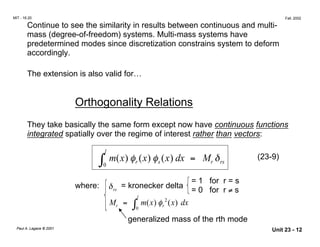

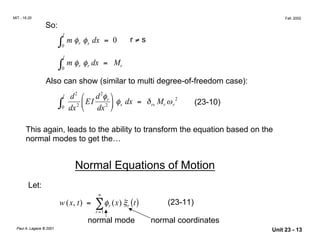

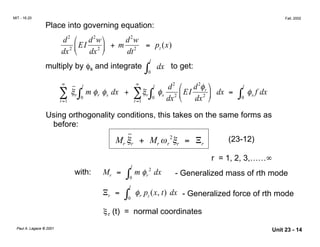

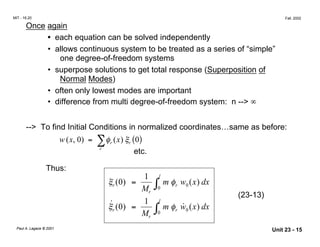

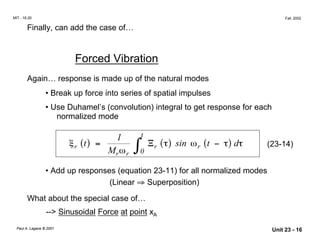

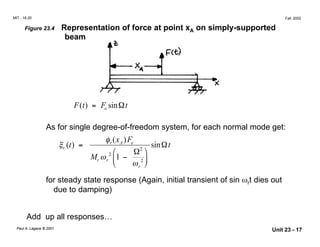

This document discusses the vibration of continuous systems such as beams. It shows that a continuous system can be modeled as having an infinite number of masses. The governing differential equation is derived and solved using normal mode analysis. Normal modes and natural frequencies are determined by applying boundary conditions. The total response is the sum of responses from each normal mode, allowing a continuous system to be treated as uncoupled single-degree-of-freedom systems. Examples are given for a simply supported beam under free and forced vibration.