The document provides operational guidance for fire and rescue services responding to incidents involving hazardous materials in the UK. It outlines the purpose, scope, and legal framework, emphasizing the importance of consistent practices and safe systems of work to enhance national resilience and interoperability. The guidance is designed for adaptability to various incident scales and includes detailed tactical and technical information on managing hazardous material situations.

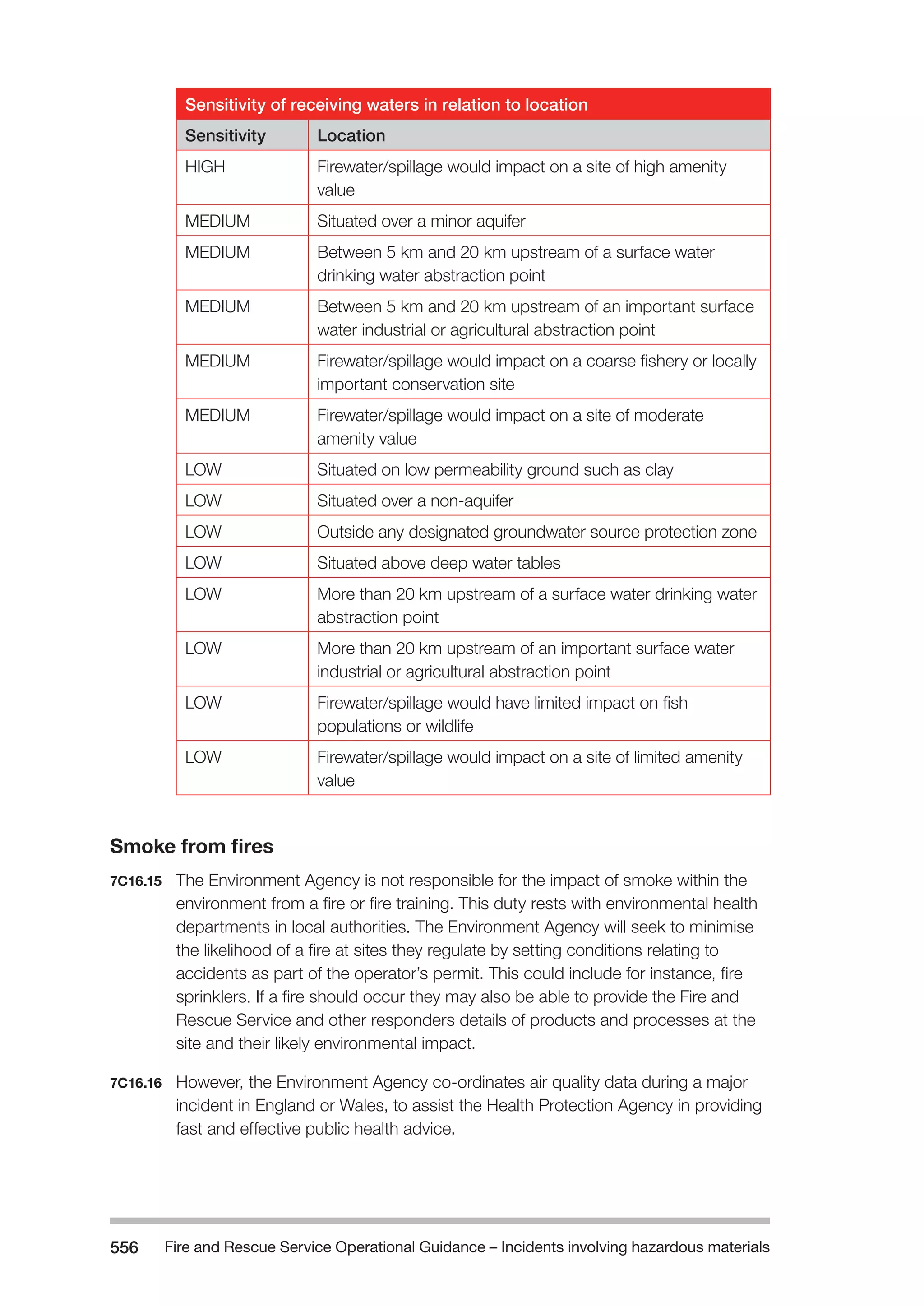

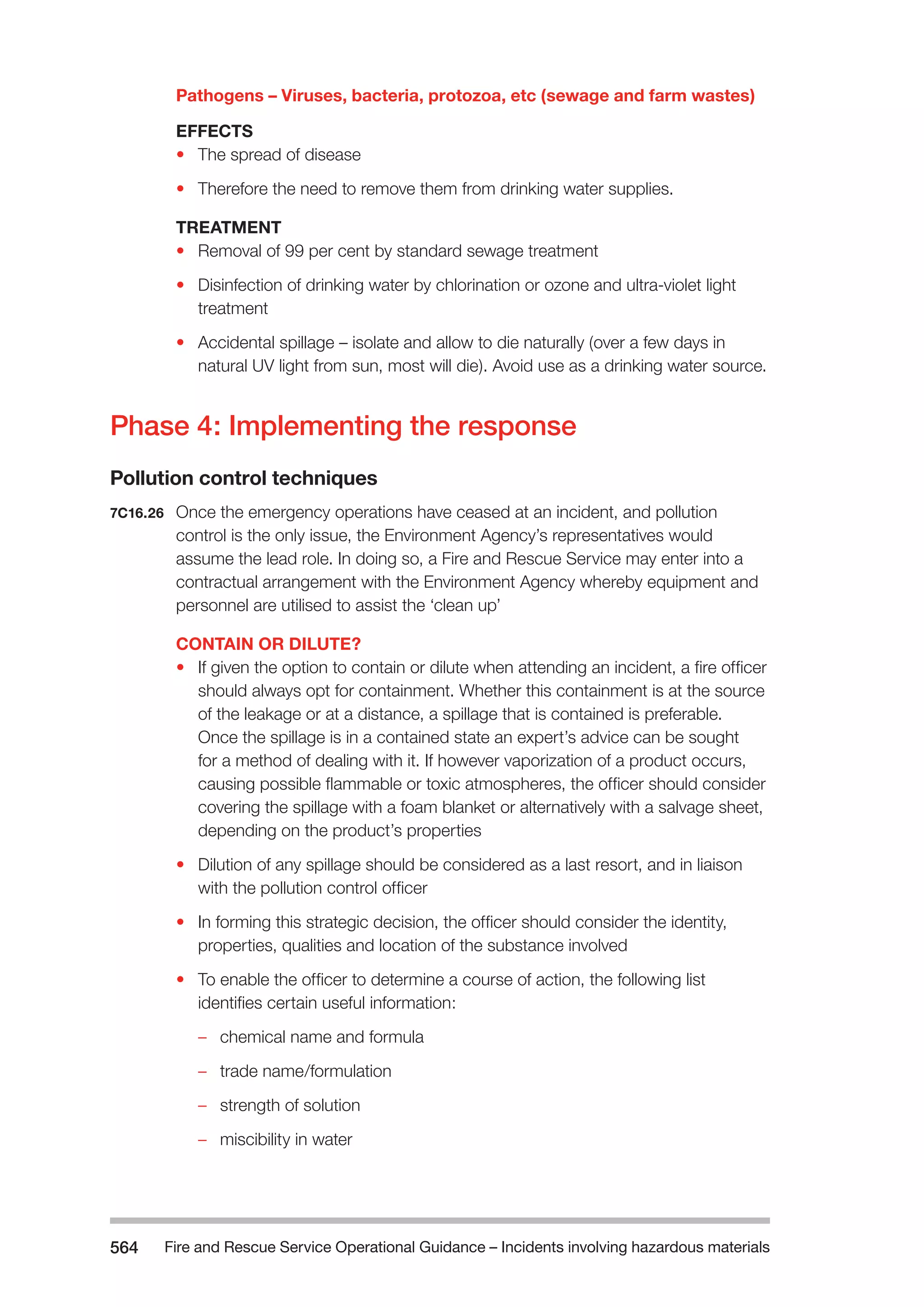

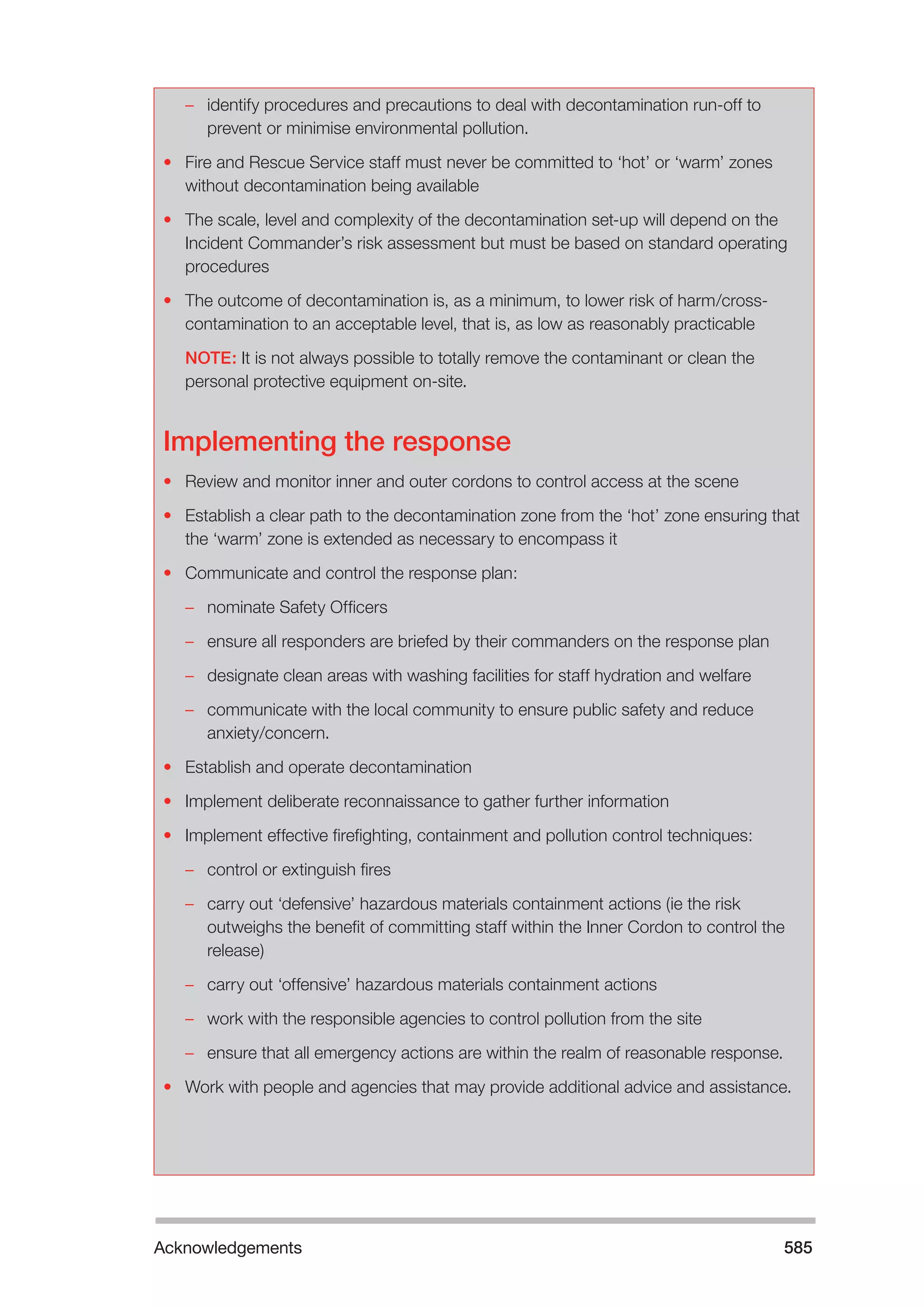

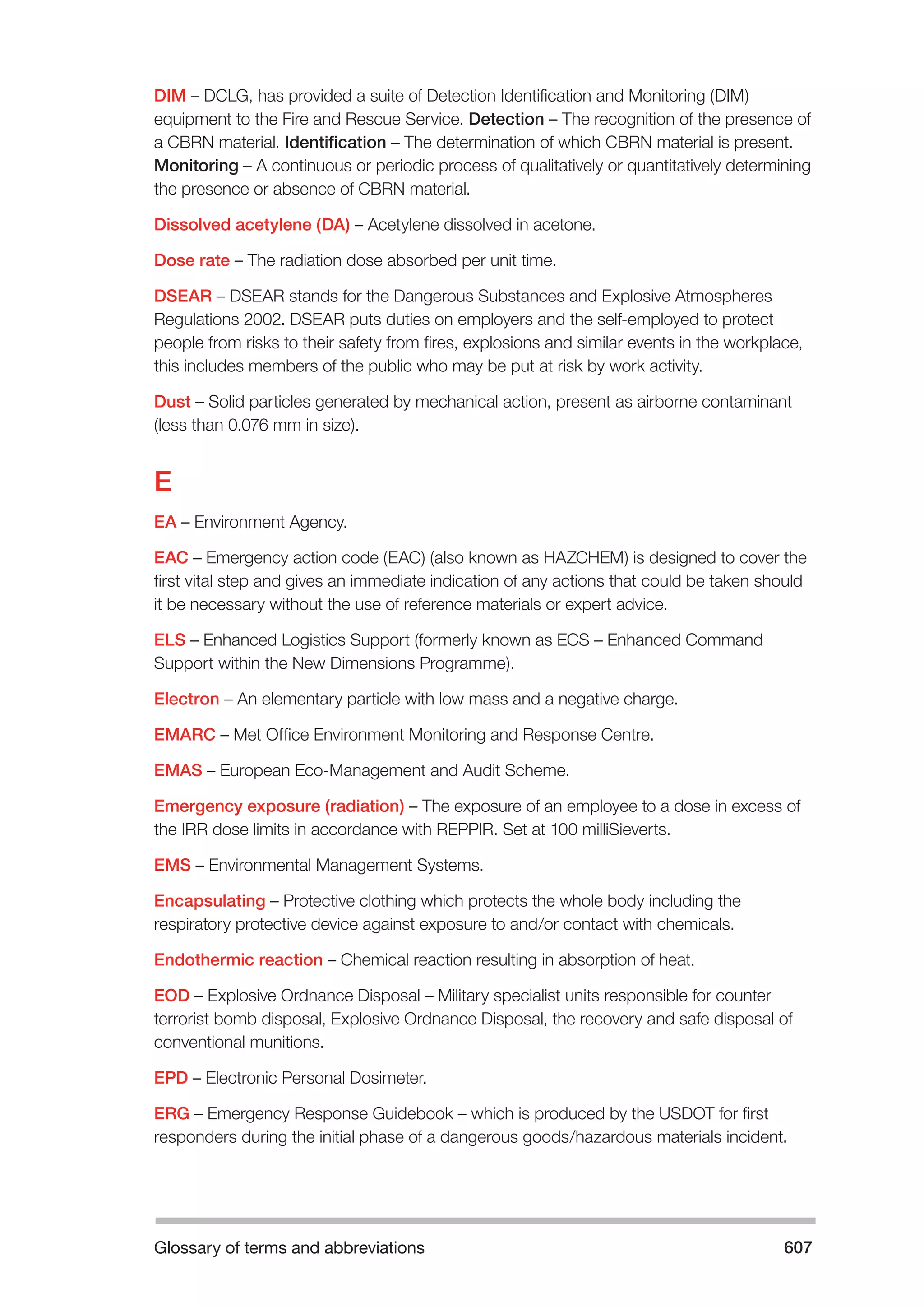

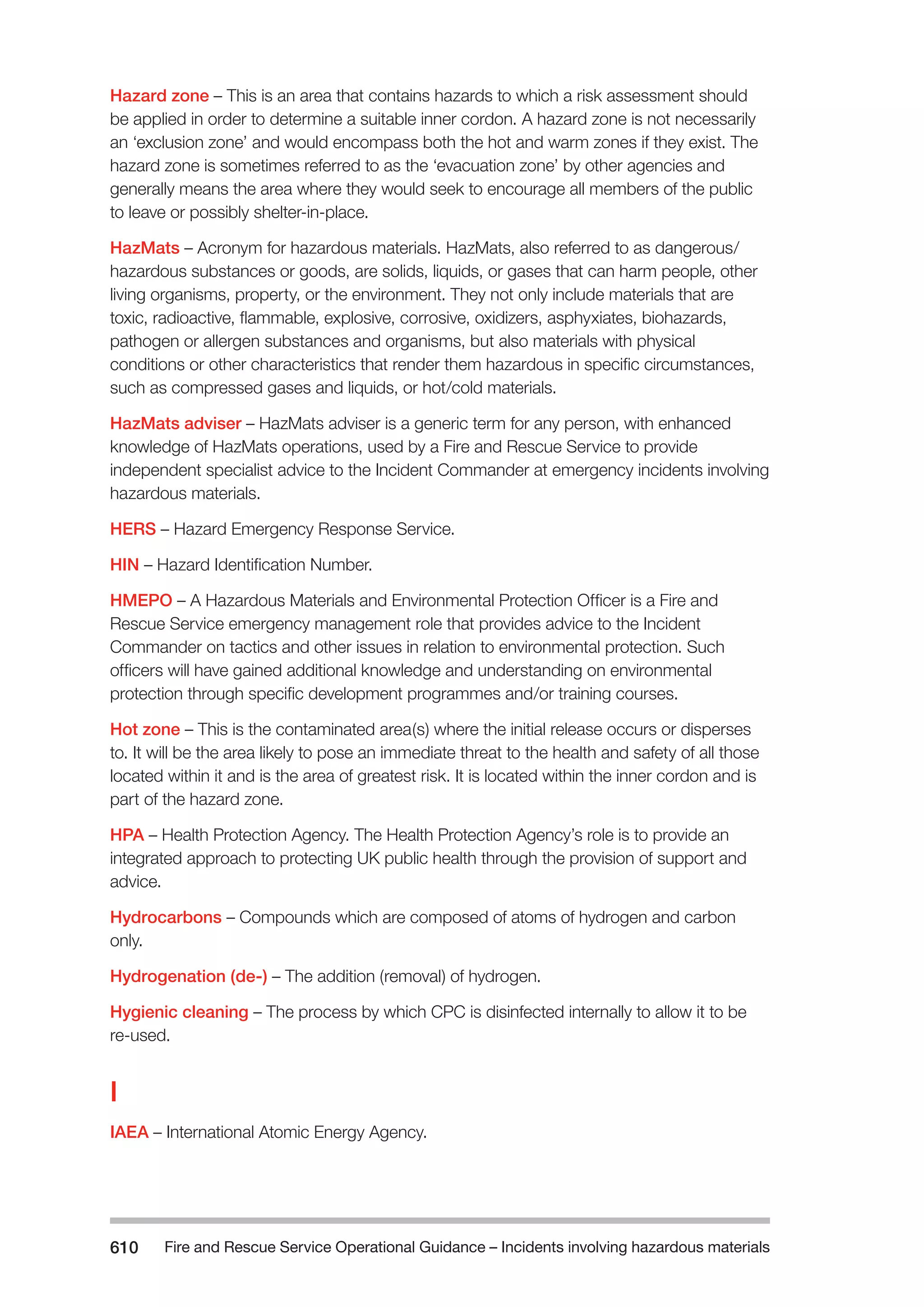

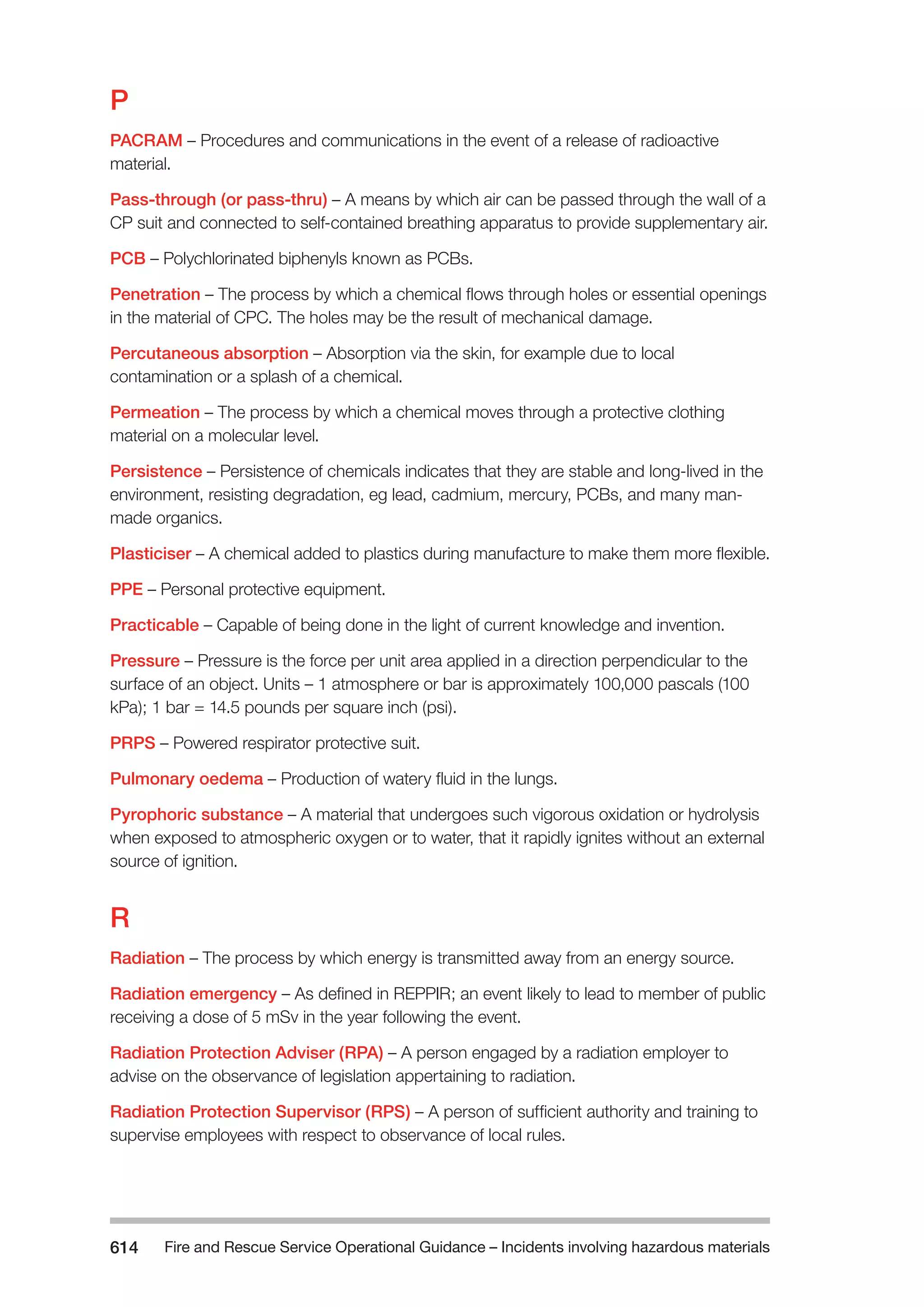

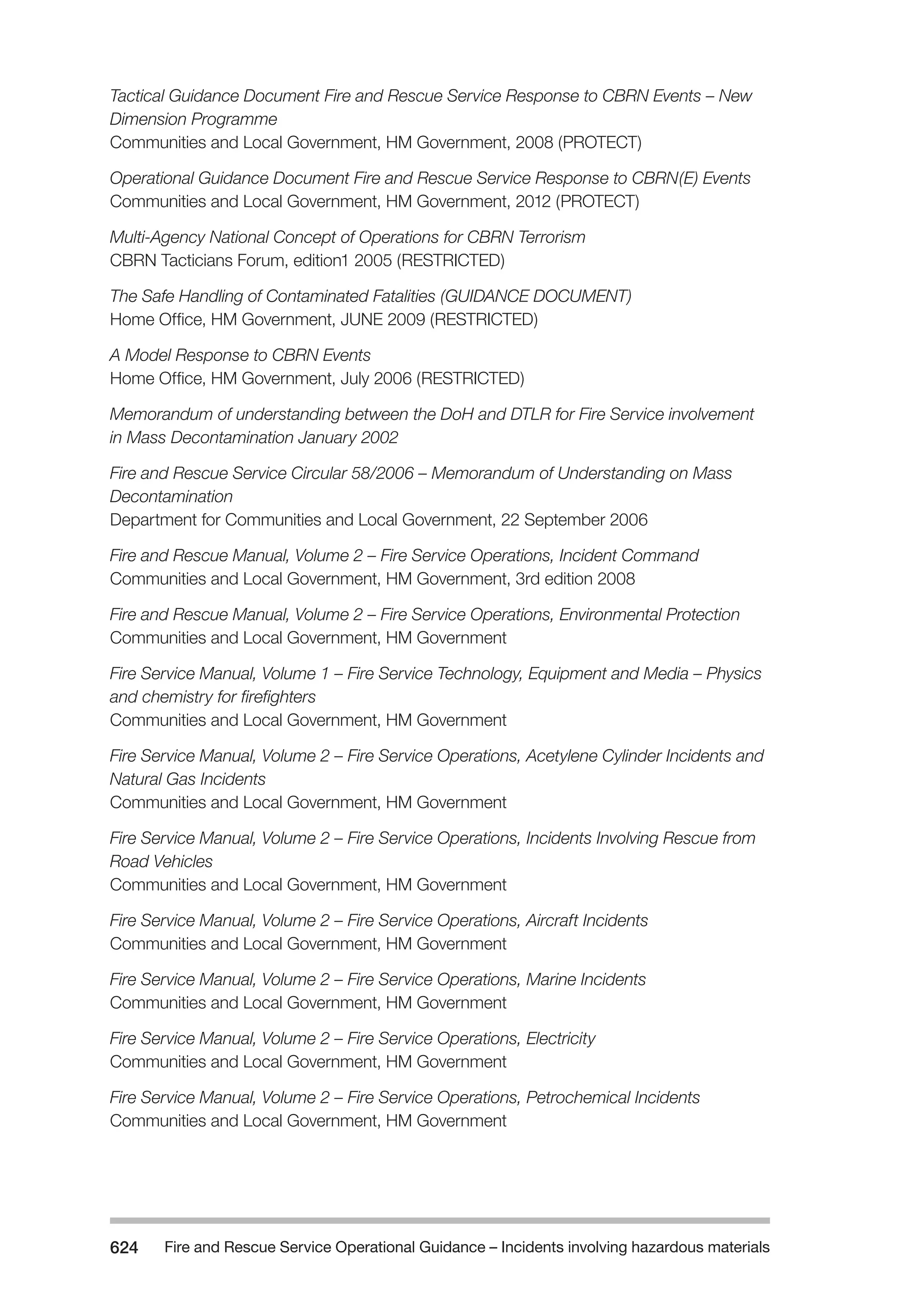

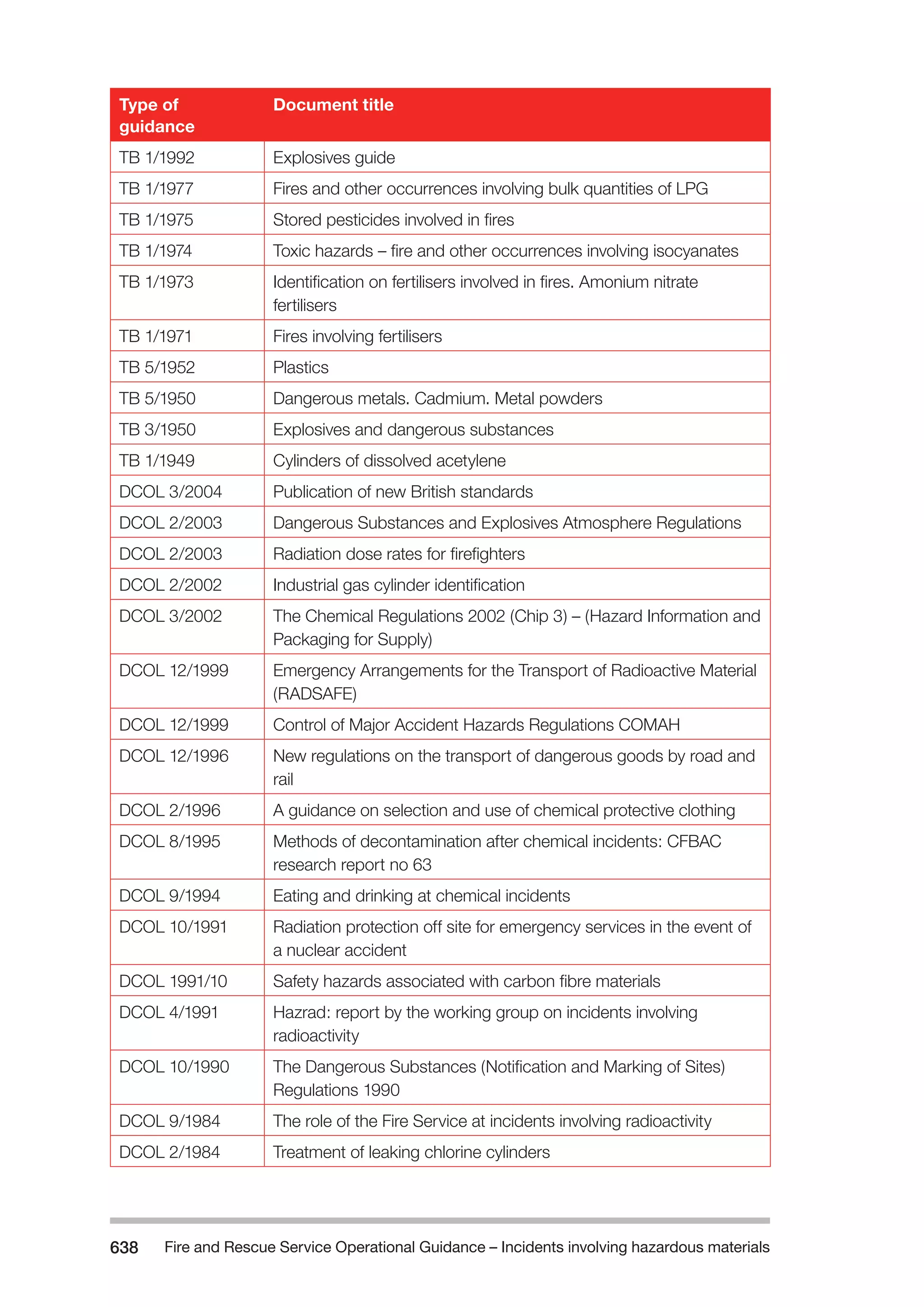

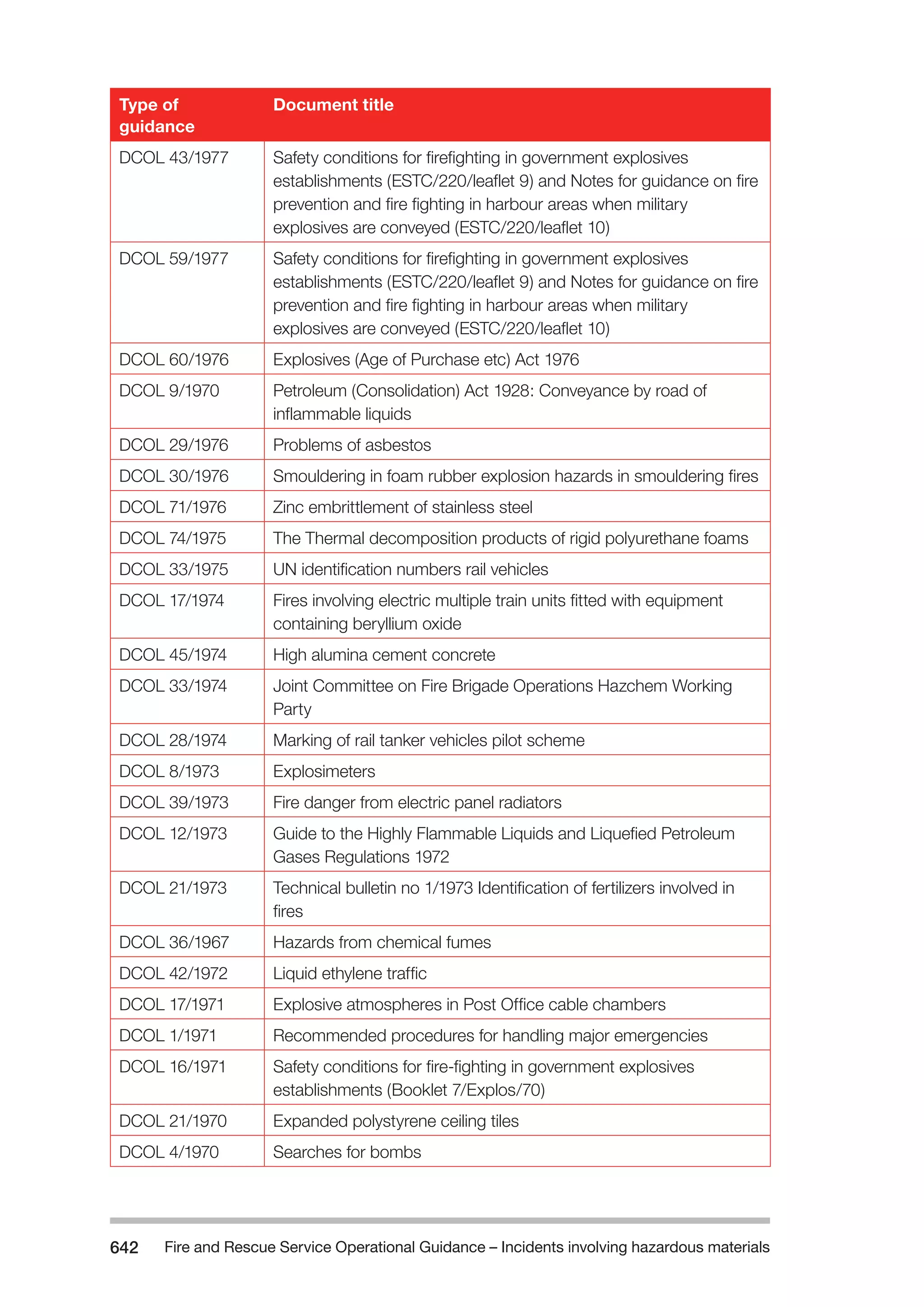

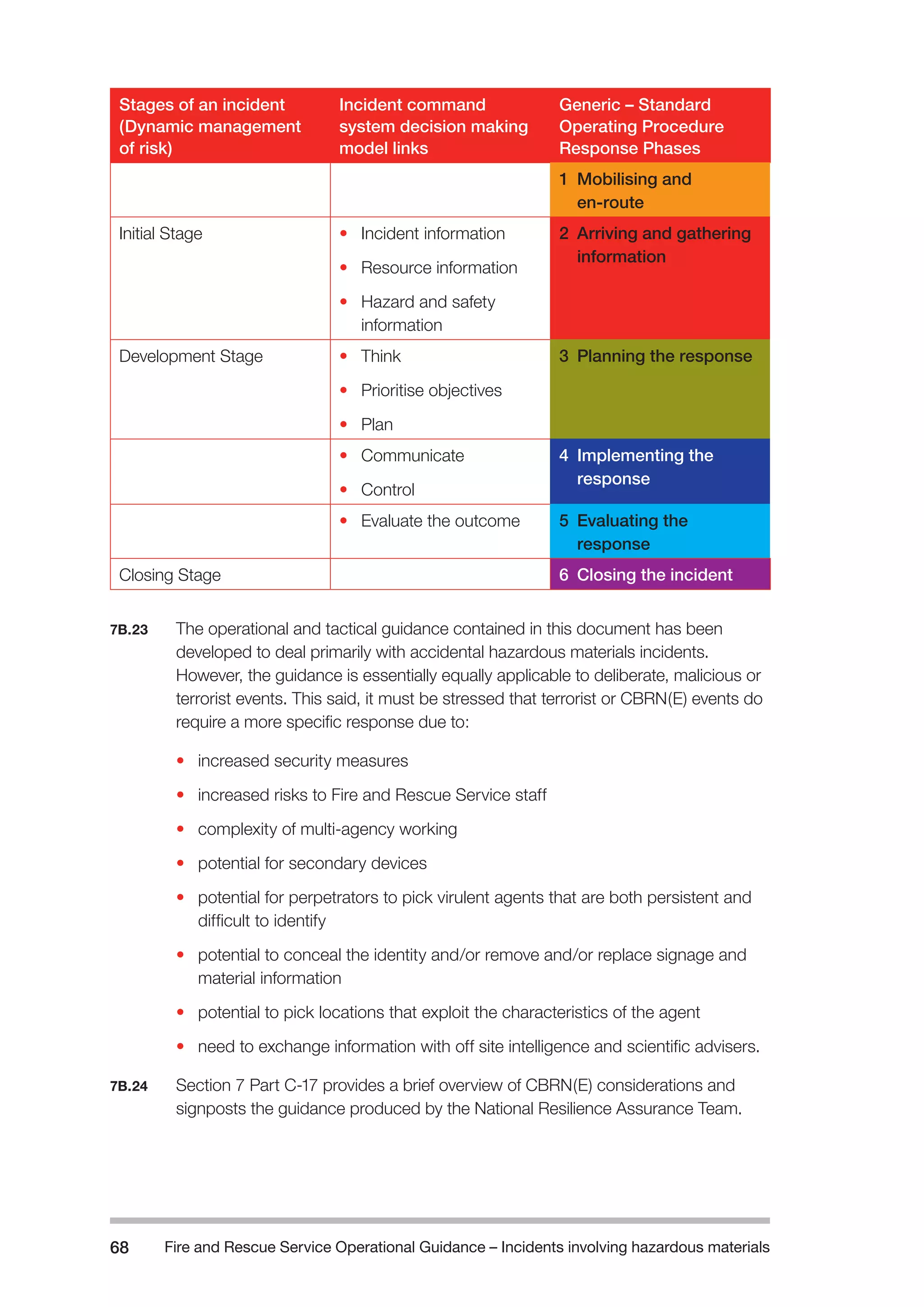

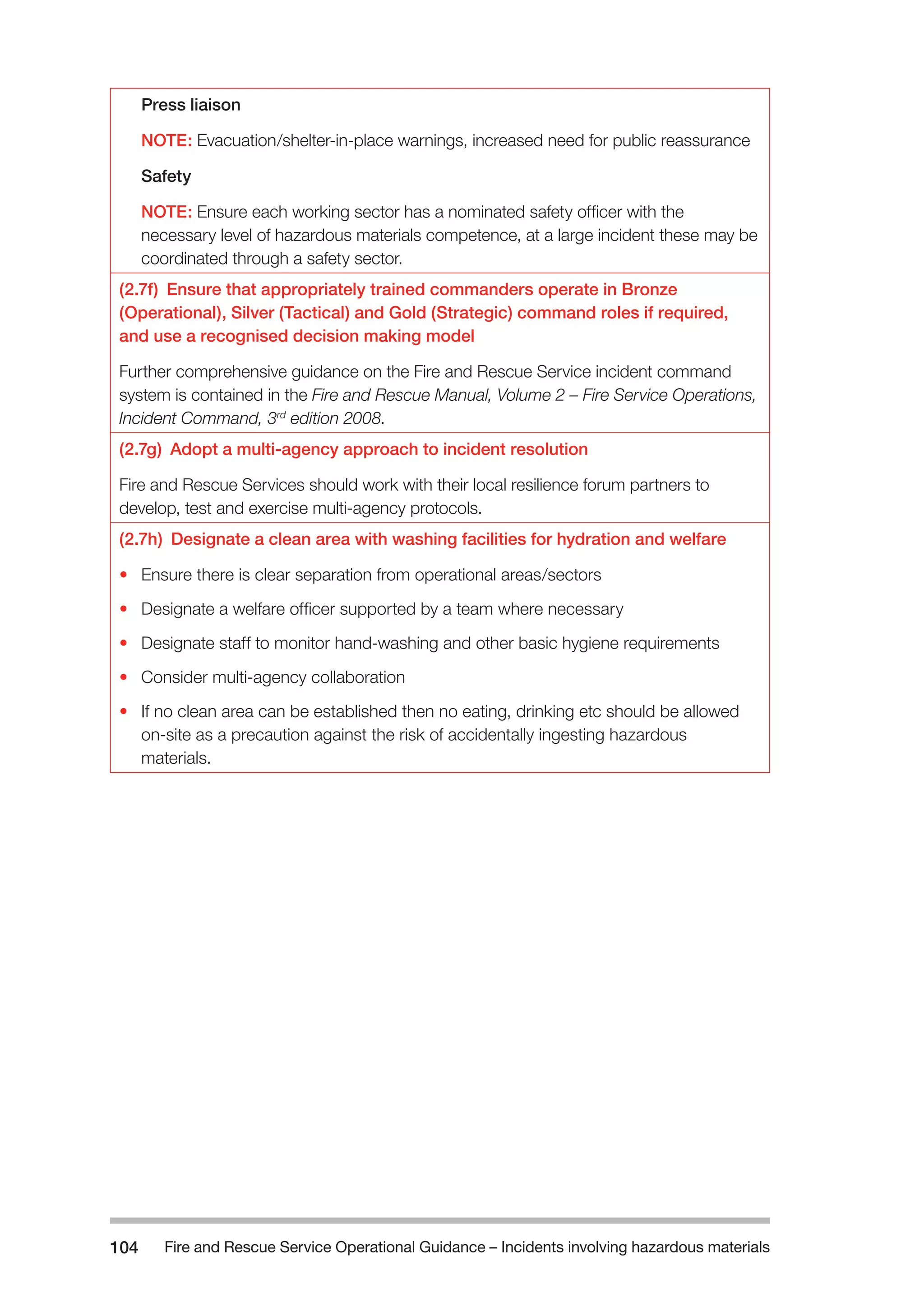

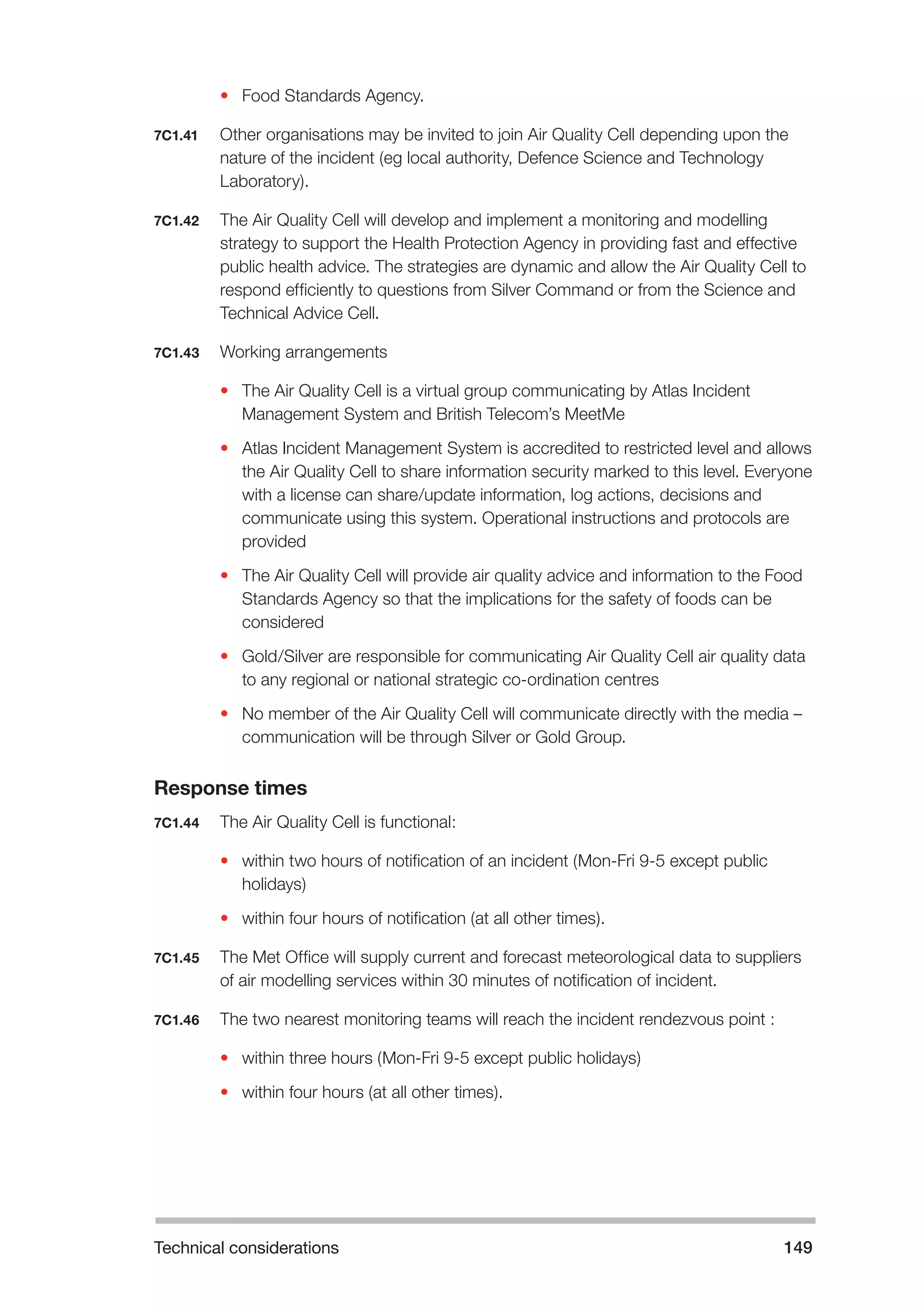

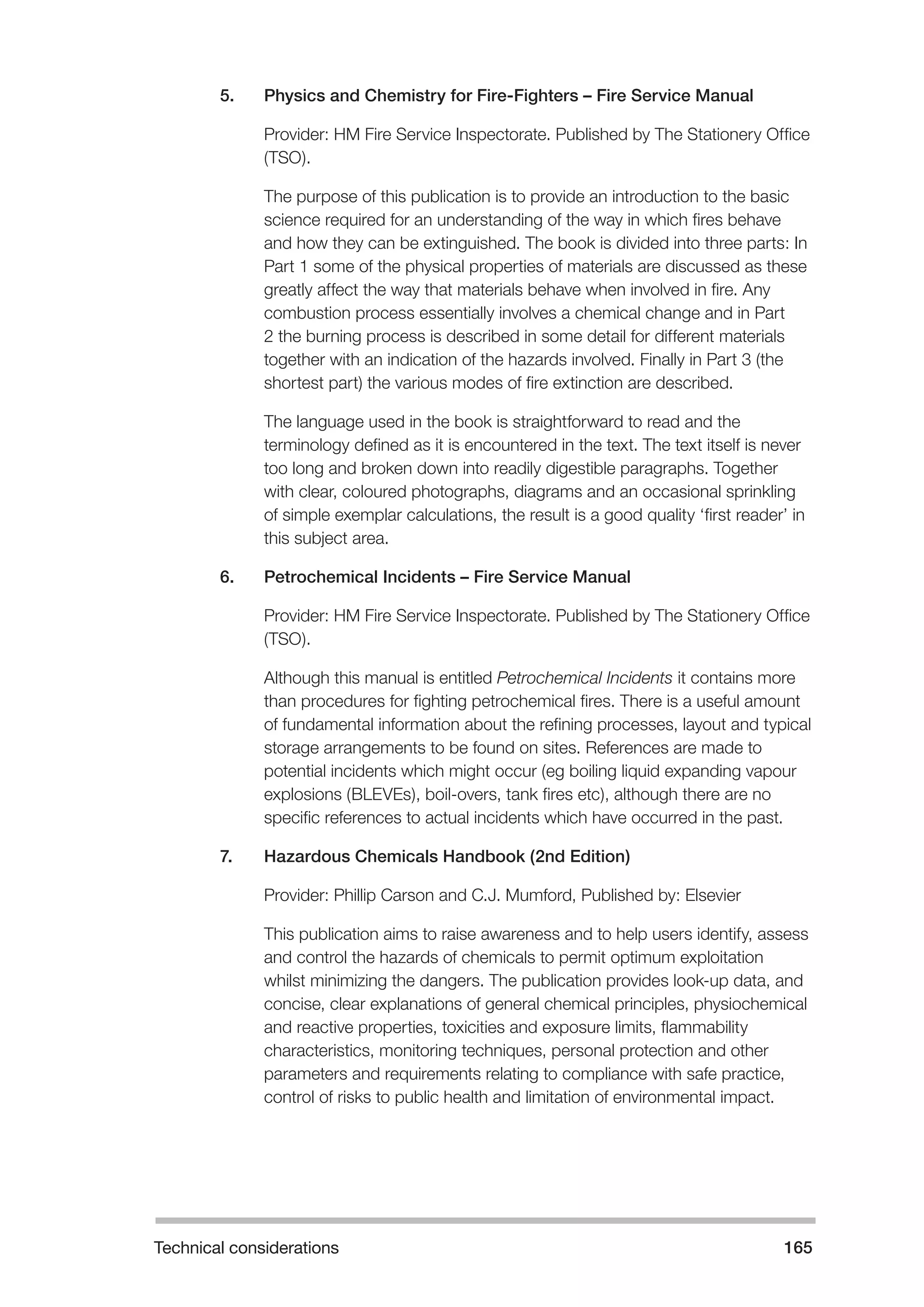

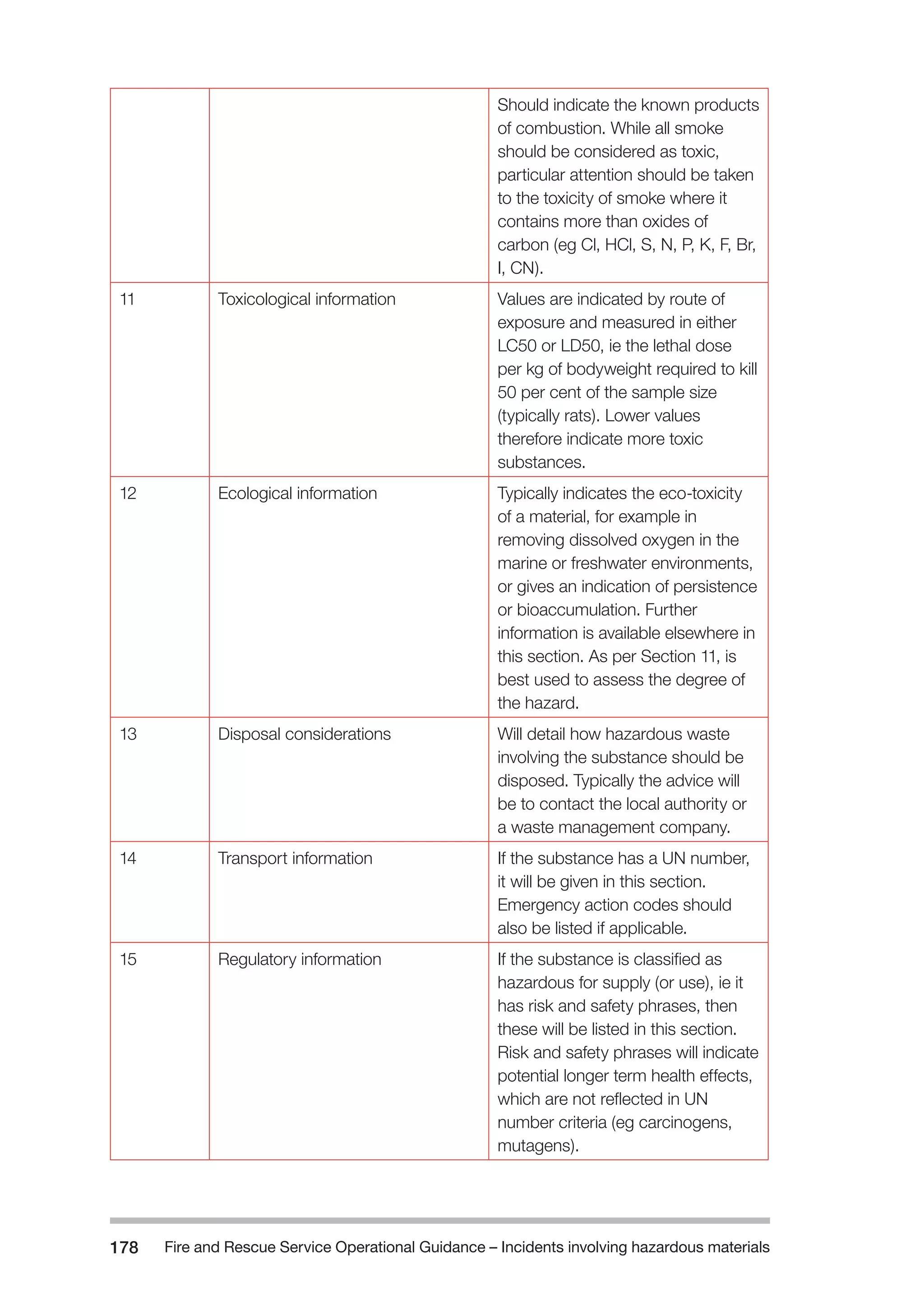

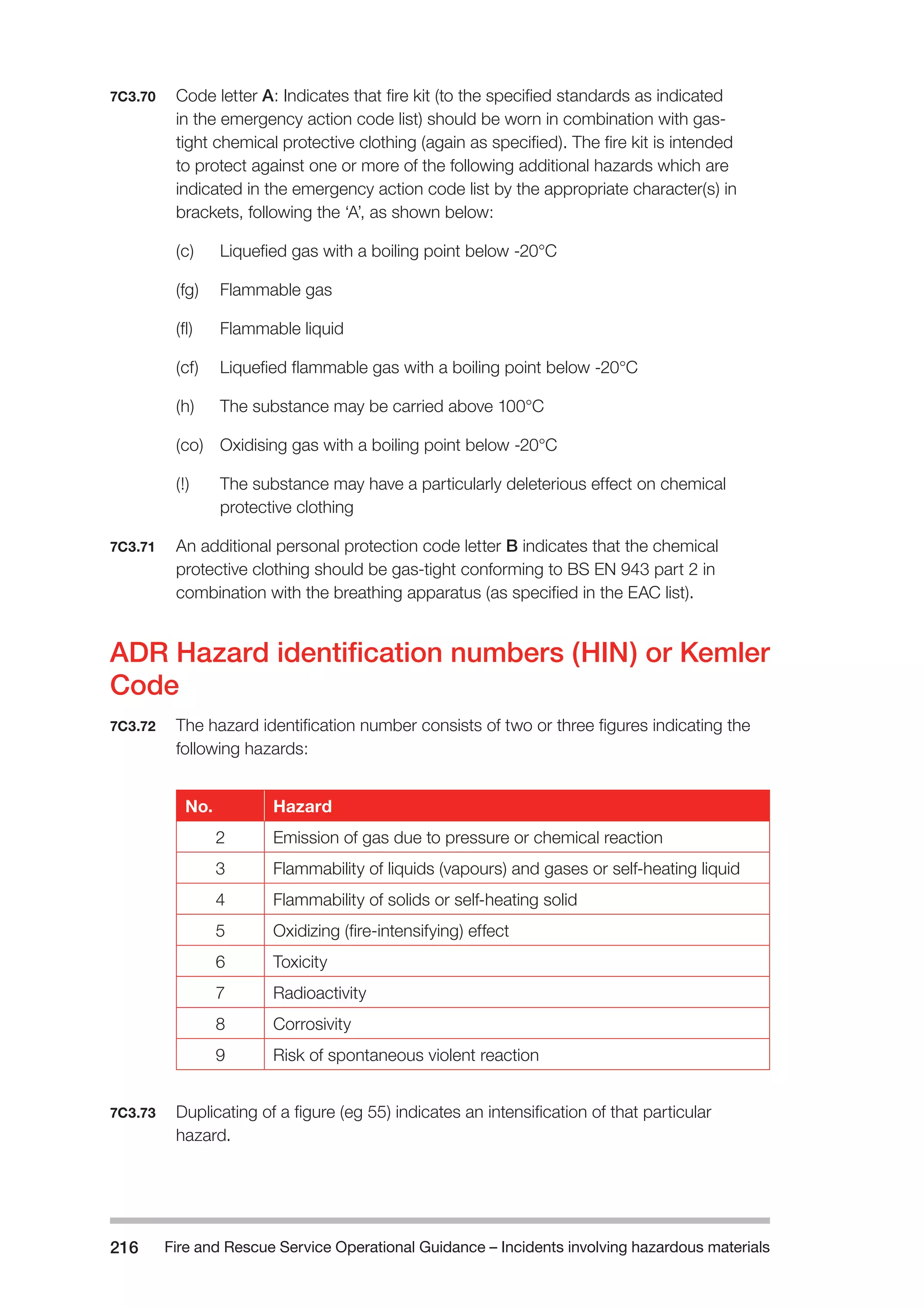

![Technical considerations 233

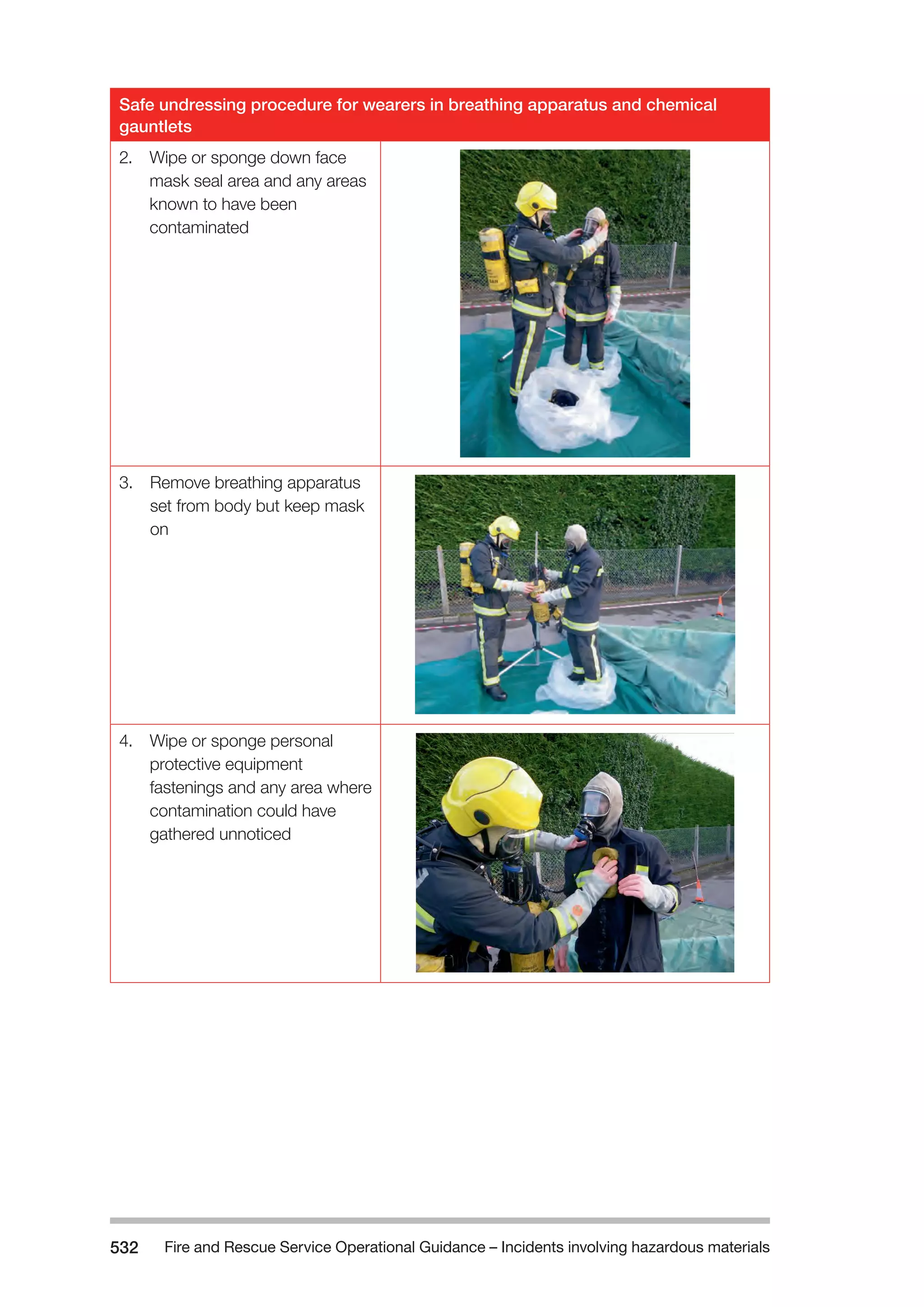

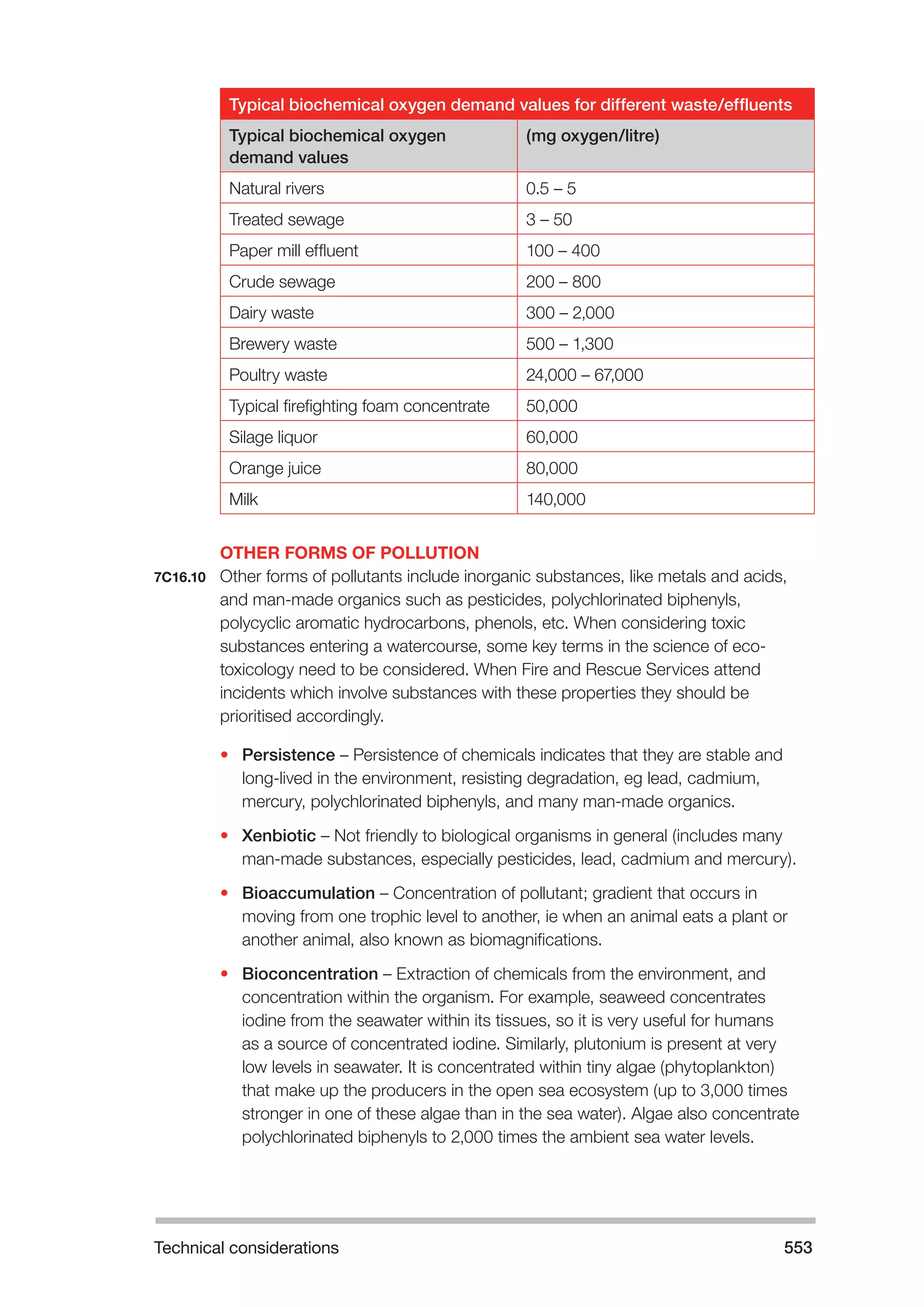

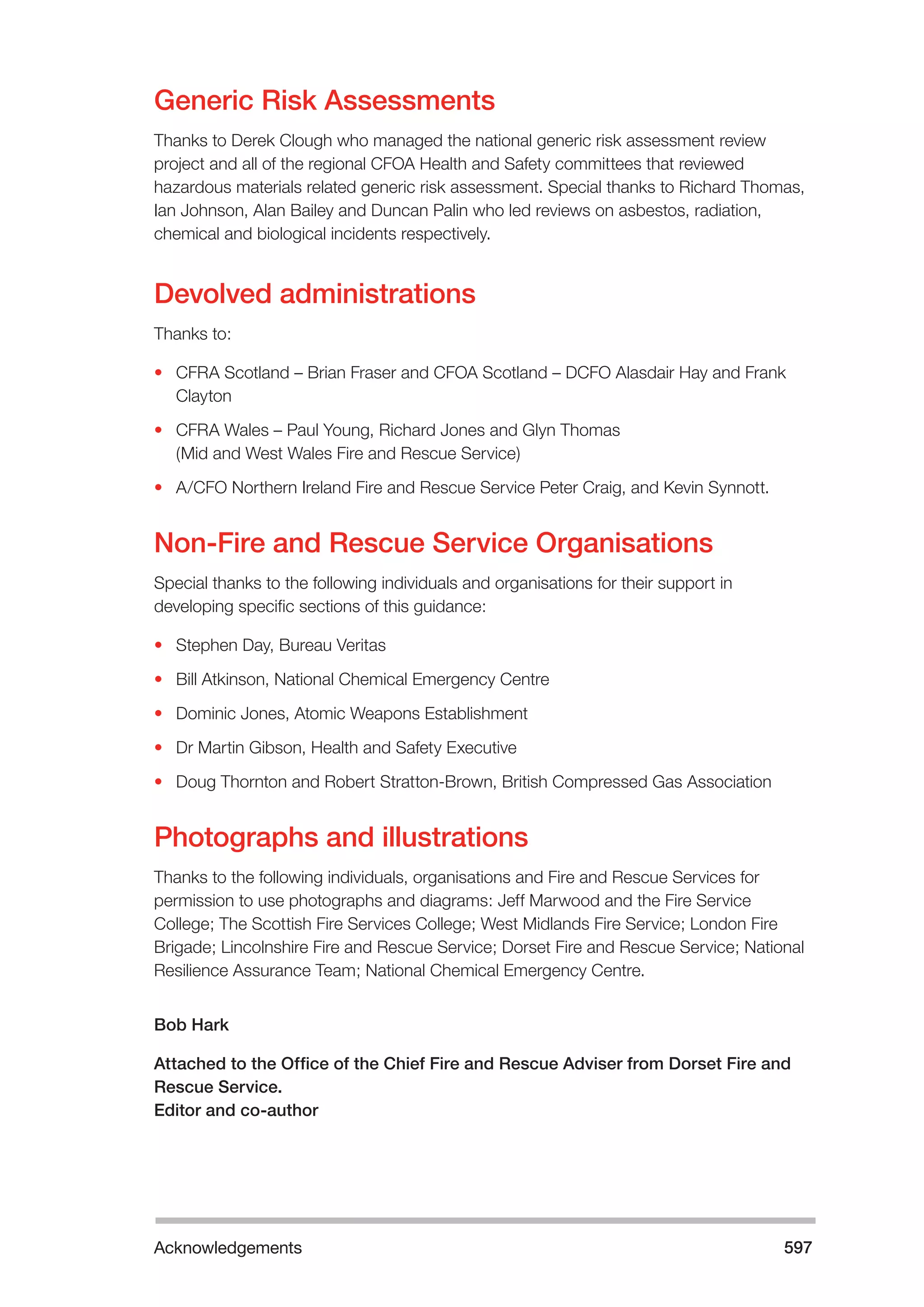

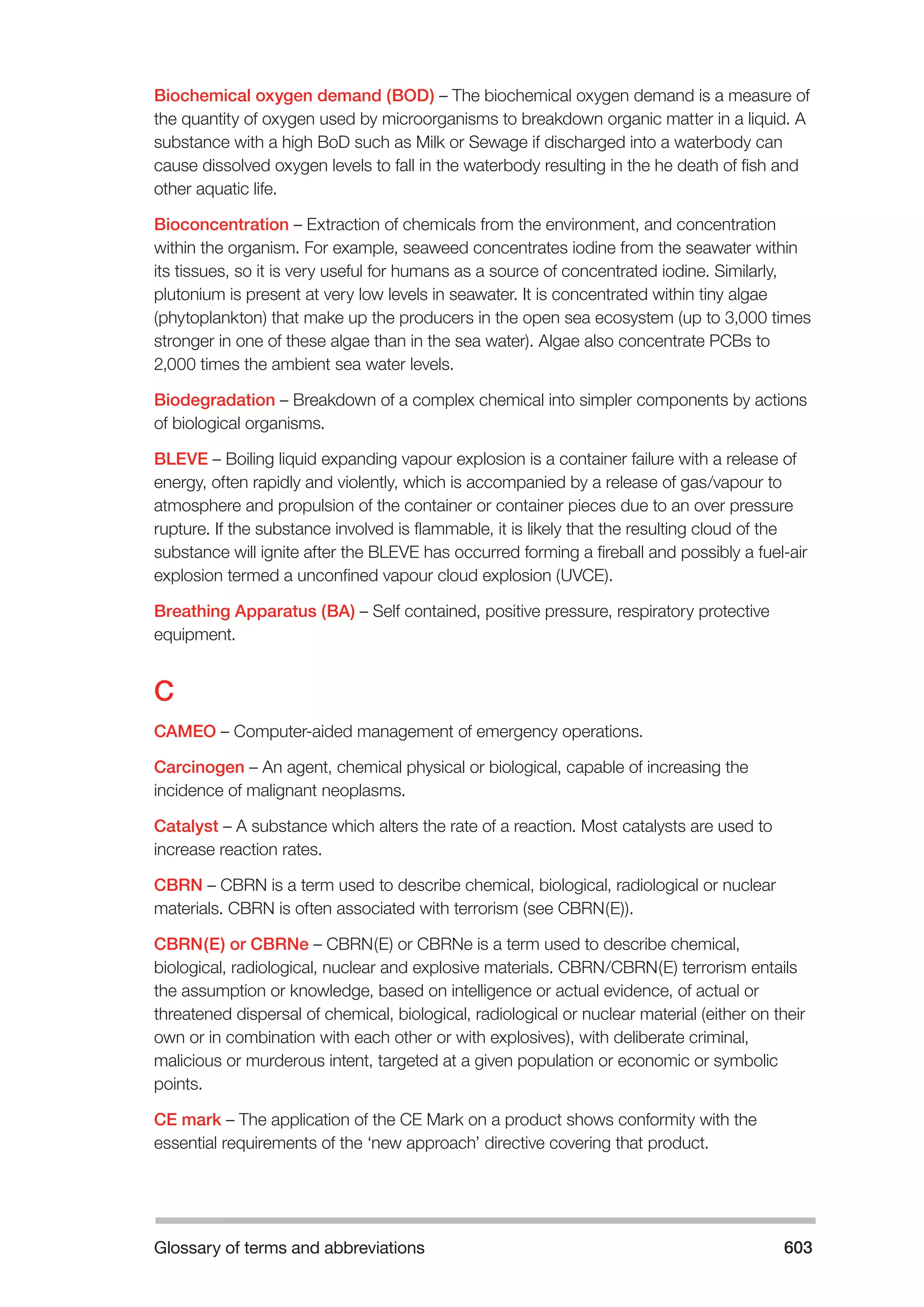

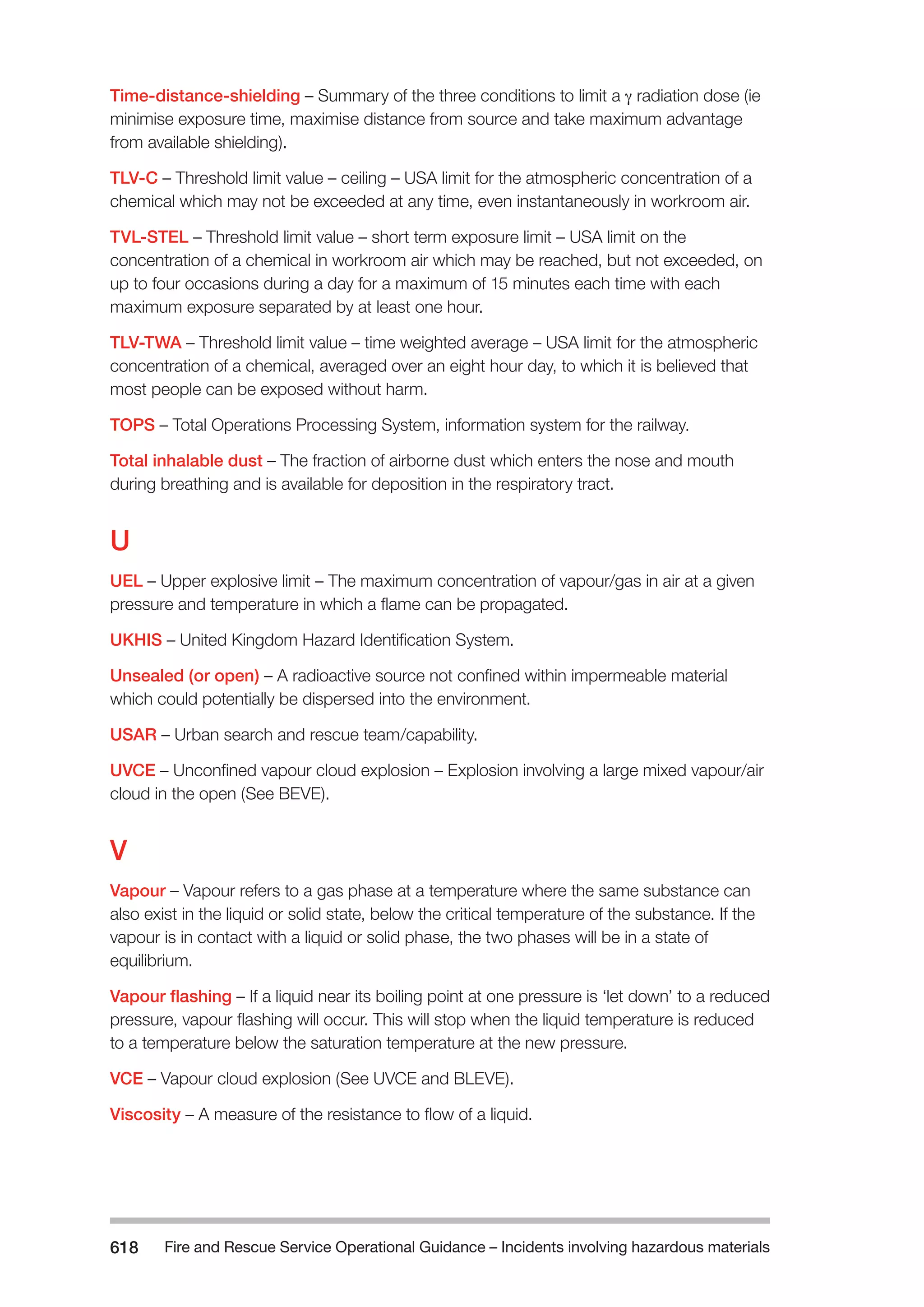

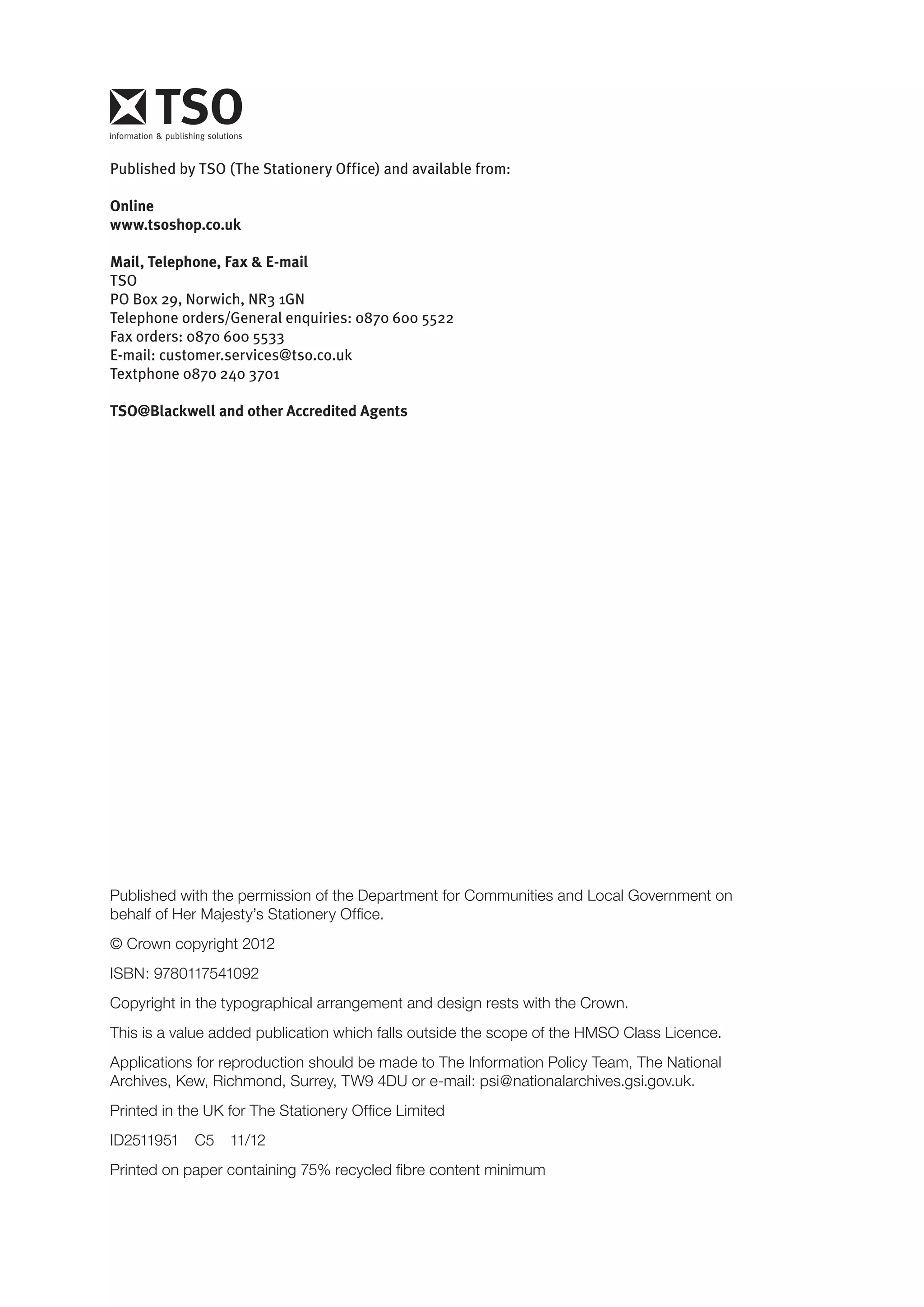

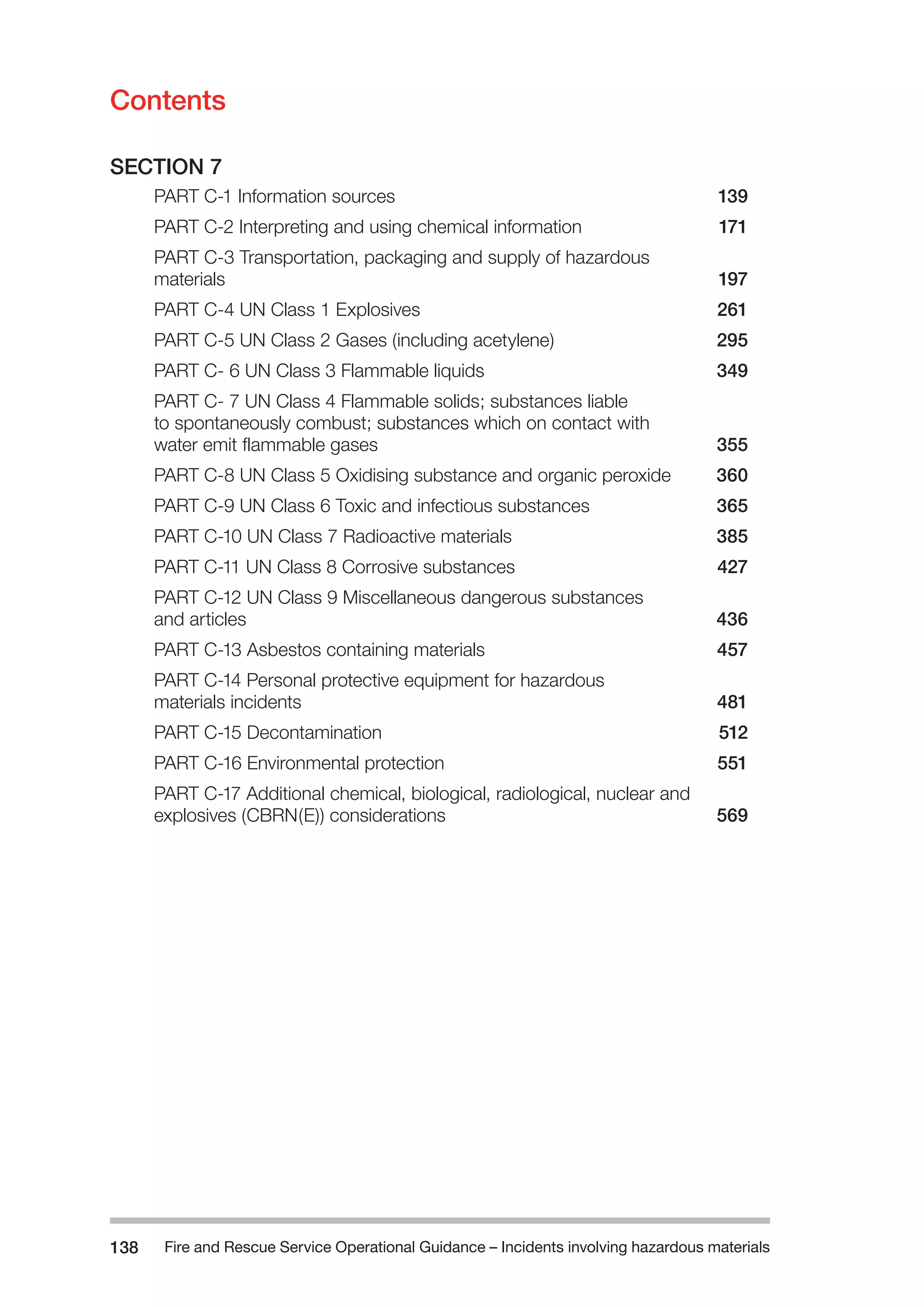

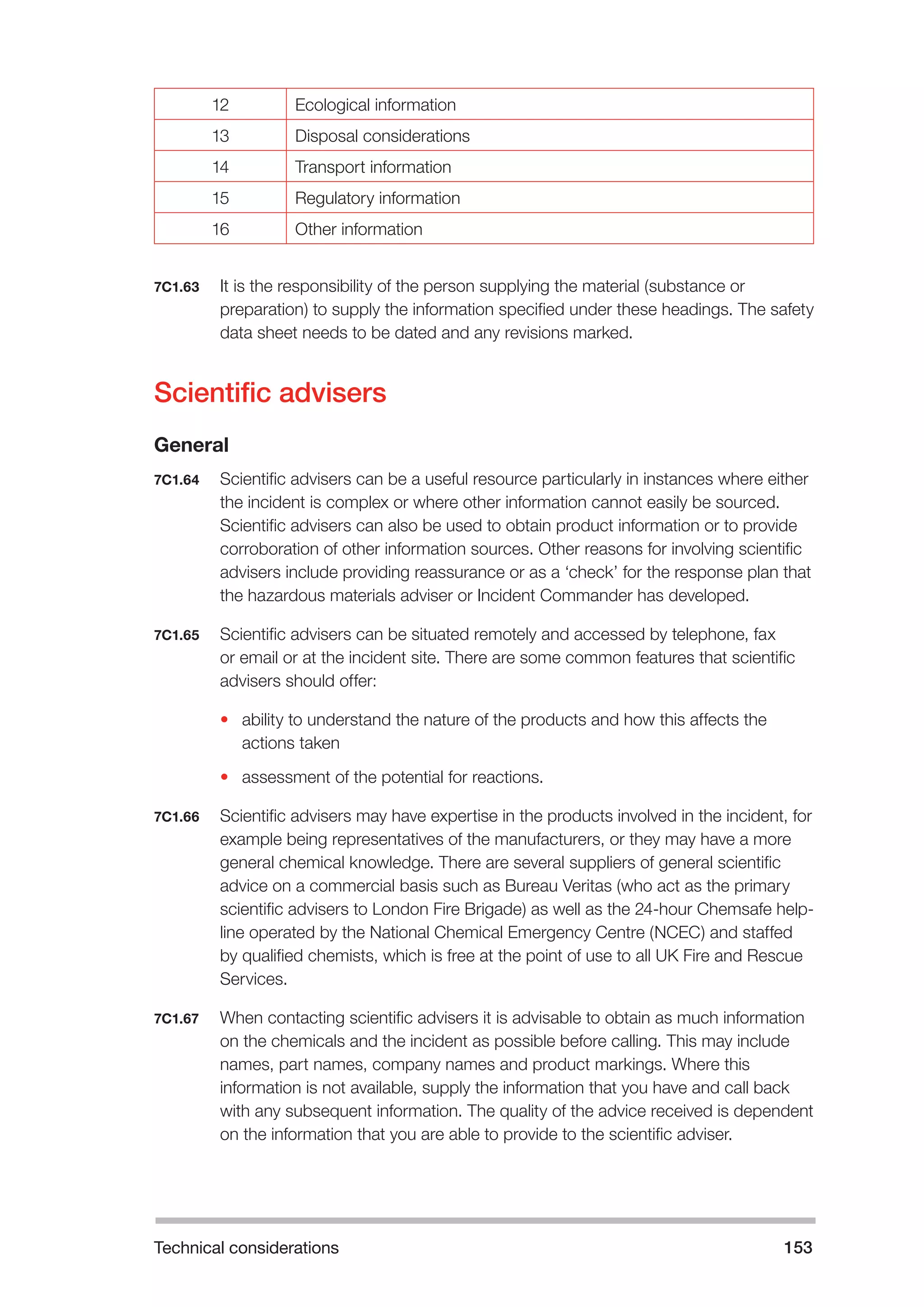

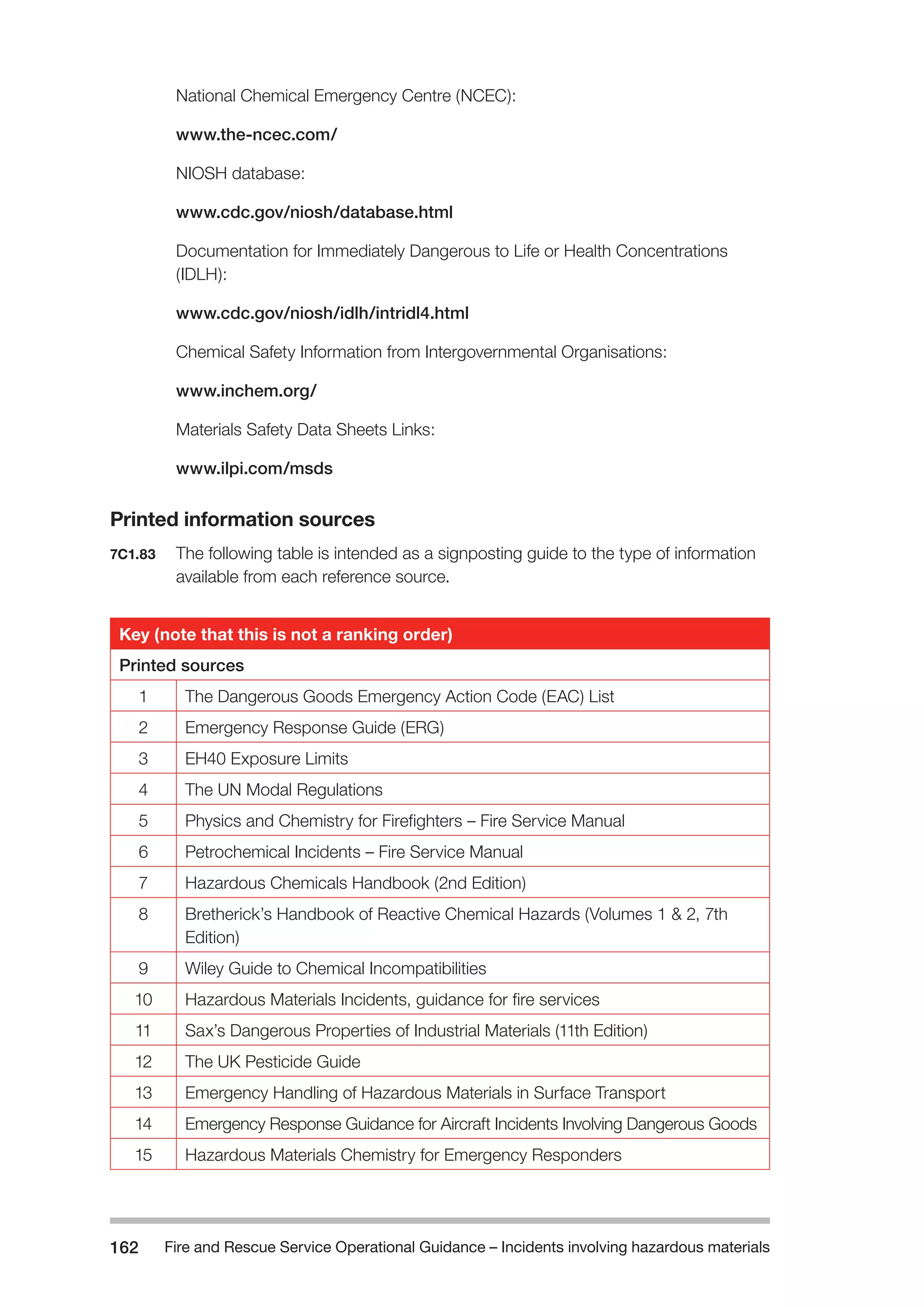

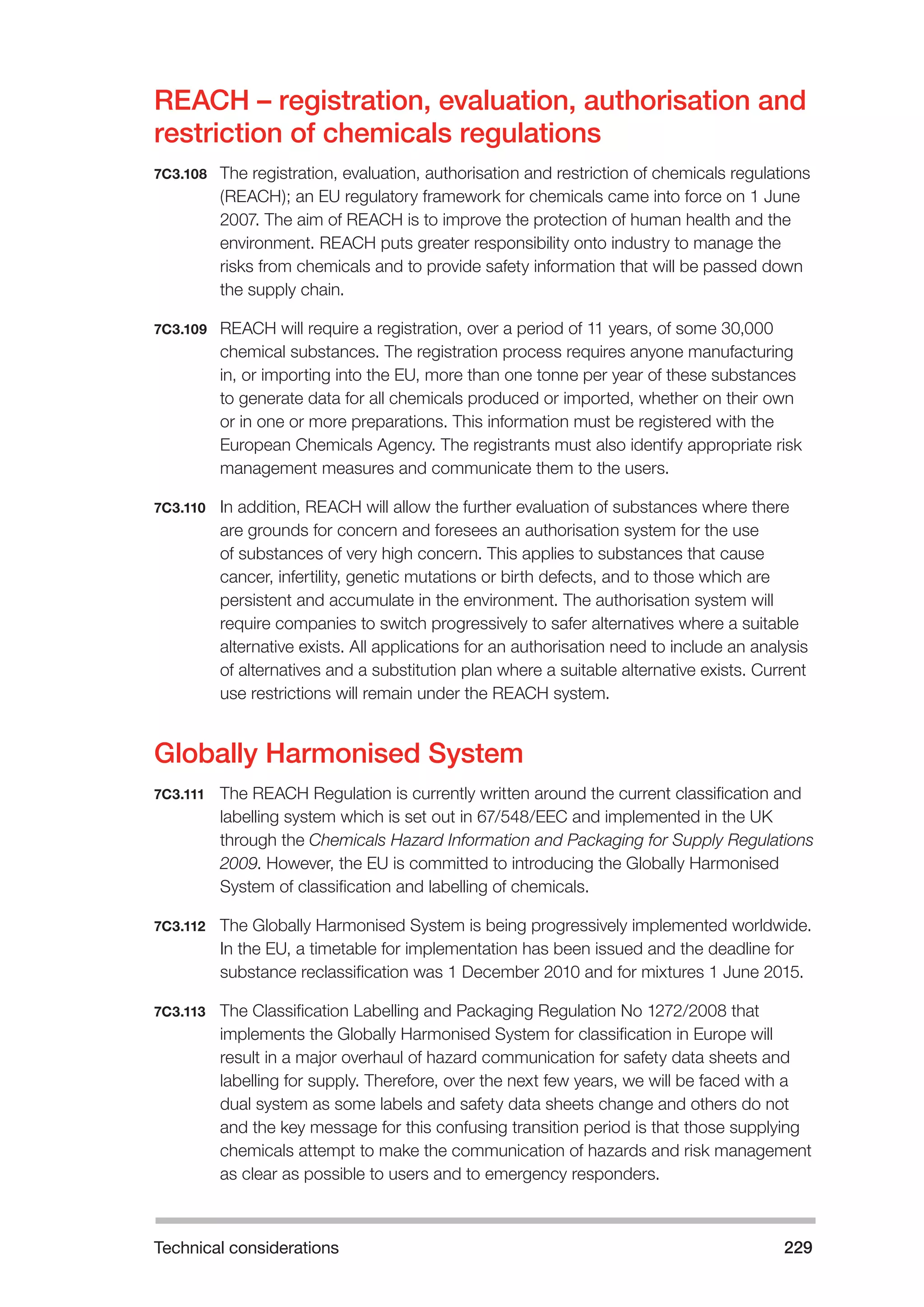

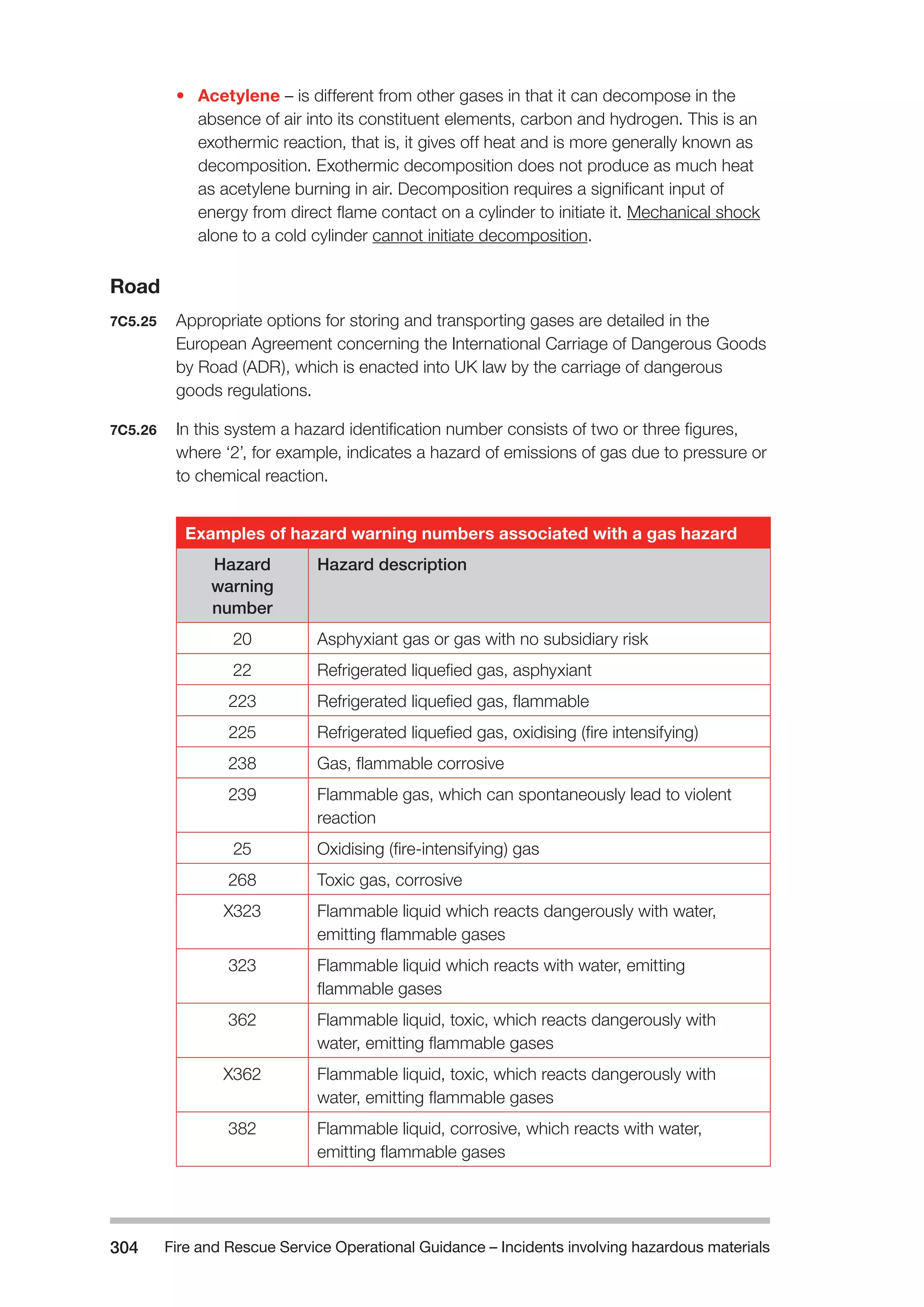

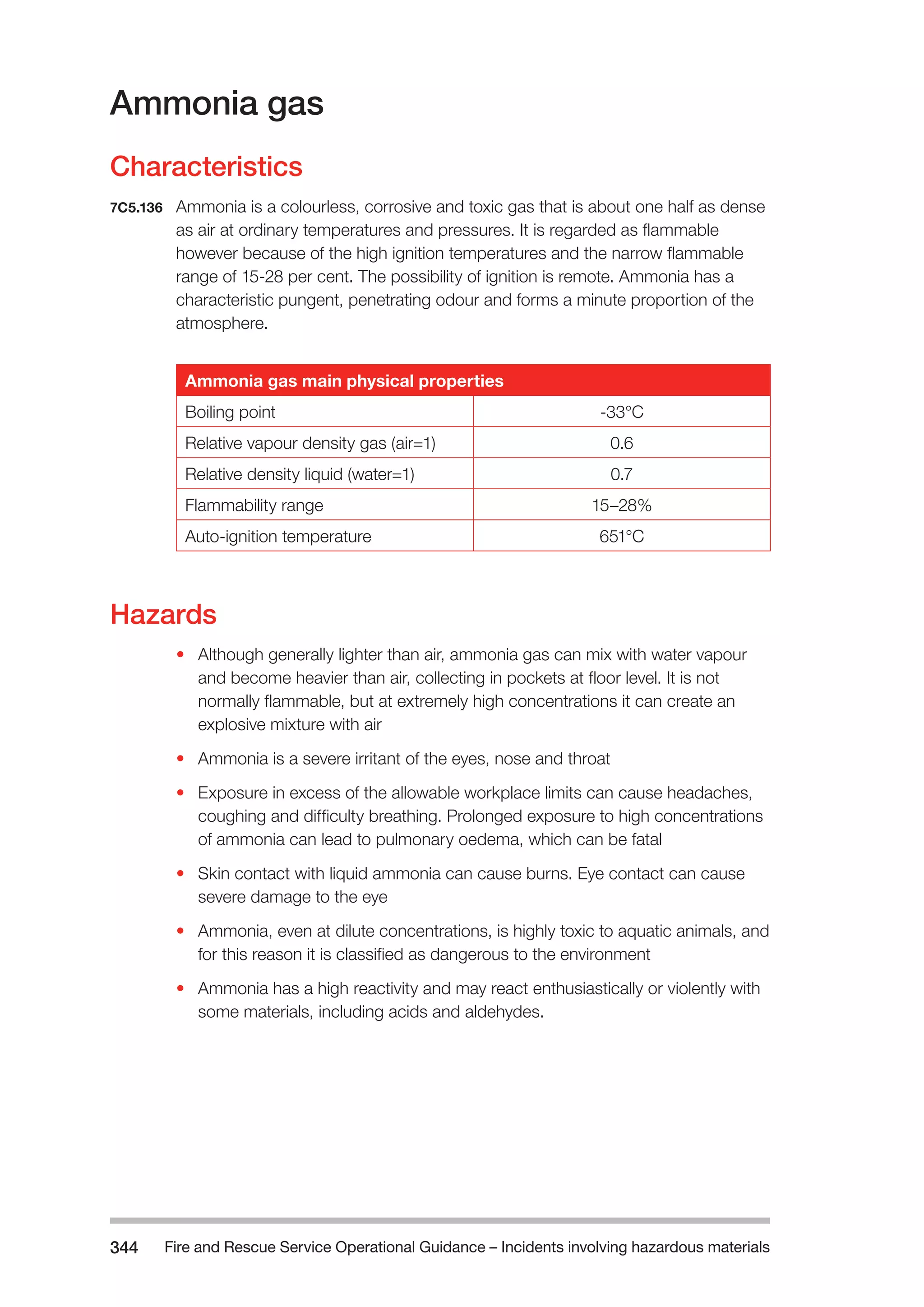

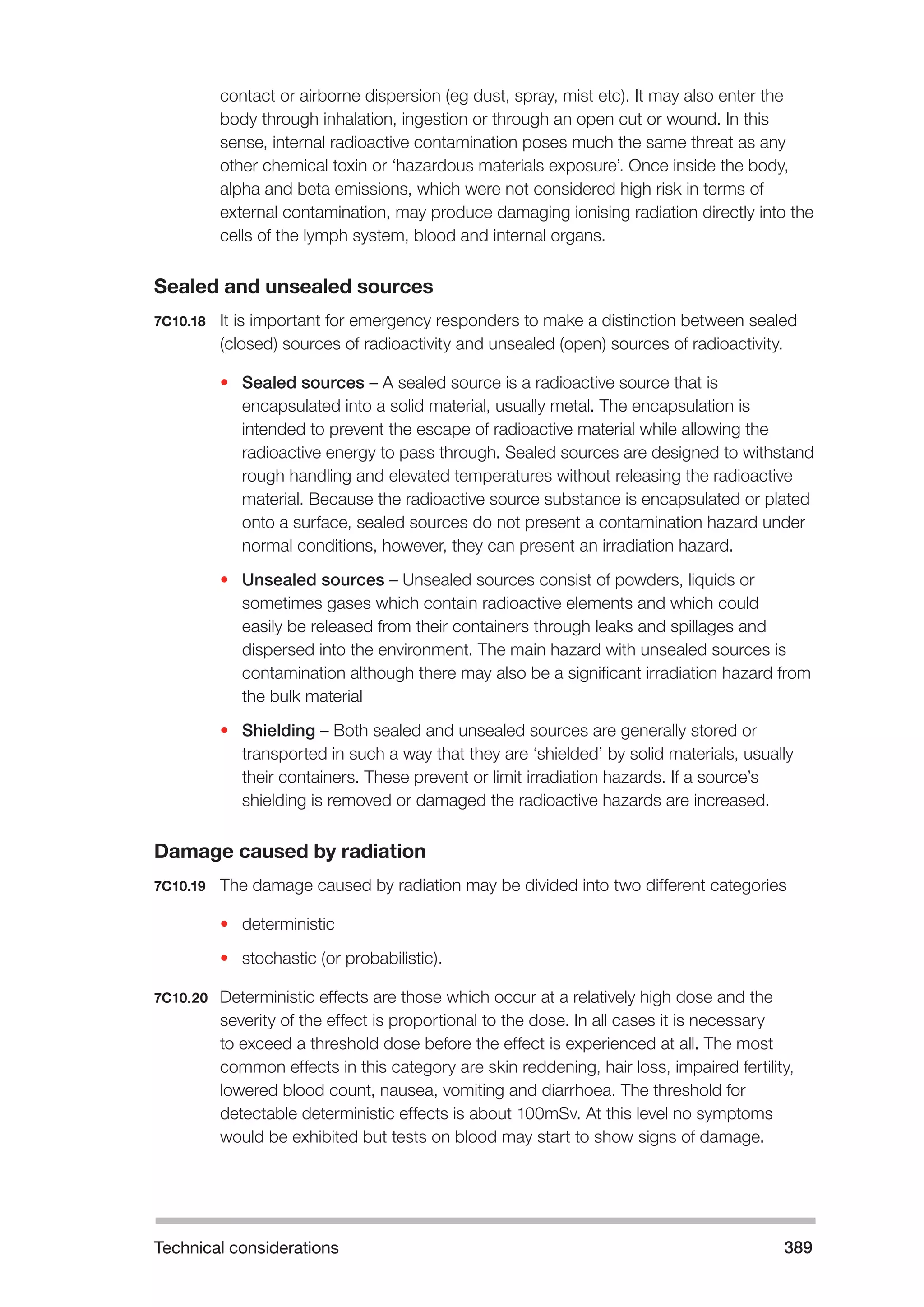

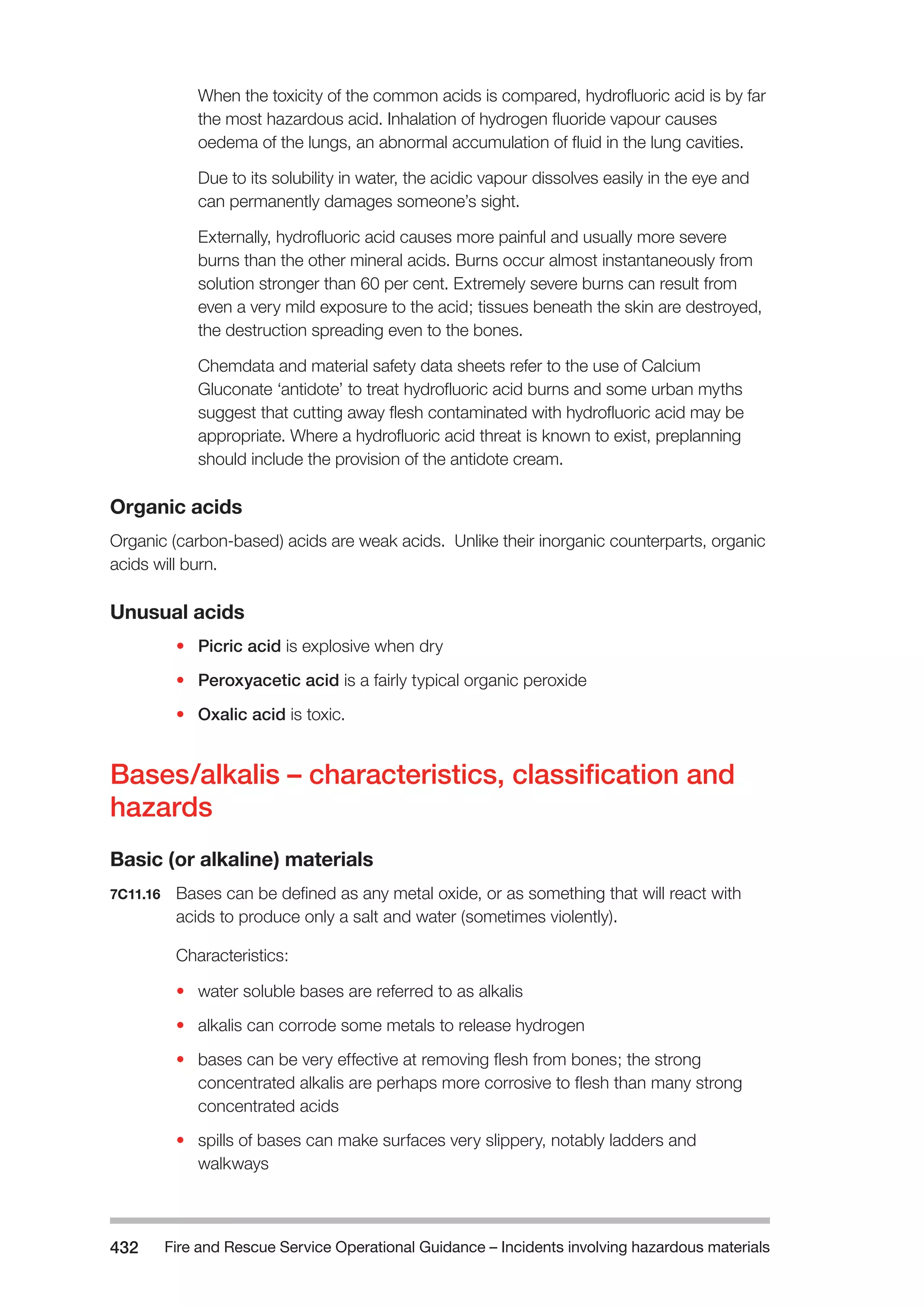

Comparison of Globally Harmonised System and Chemicals Hazard

Information and Packaging for Supply Regulations 2009 (CHIP)

labeling advice

Existing Chemicals Hazard

Information and Packaging for

Supply Regulations 2009 (CHIP)

labelling system

Globally Harmonised System

labelling

Risk phrases

Highly flammable

Very toxic by inhalation

Causes burns

Hazard statements

Highly flammable liquid and vapour

Fatal if inhaled

Causes severe skin burns and eye

damage

Safety phrases

Keep container tightly closed

Avoid contact with skin and eyes

Wear suitable protective clothing

Precautionary statements

Keep container tightly closed

Do not get in eyes, on skin or on

clothing

Wear protective clothing

[manufacturer/supplier to specify]

Example of Globally Harmonised System compliant supply labels on

chemical products](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7rbqzs77riklyjybirhl-signature-8ae49c26427c42a89a6d4352195b02a6095bd9fa5df6c0500639463b6450e515-poli-140828111115-phpapp02/75/The-Fire-and-Rescue-Service-Books-is-a-guidance-for-organize-a-safe-system-of-work-on-the-incident-ground-with-hazardous-materials-225-2048.jpg)

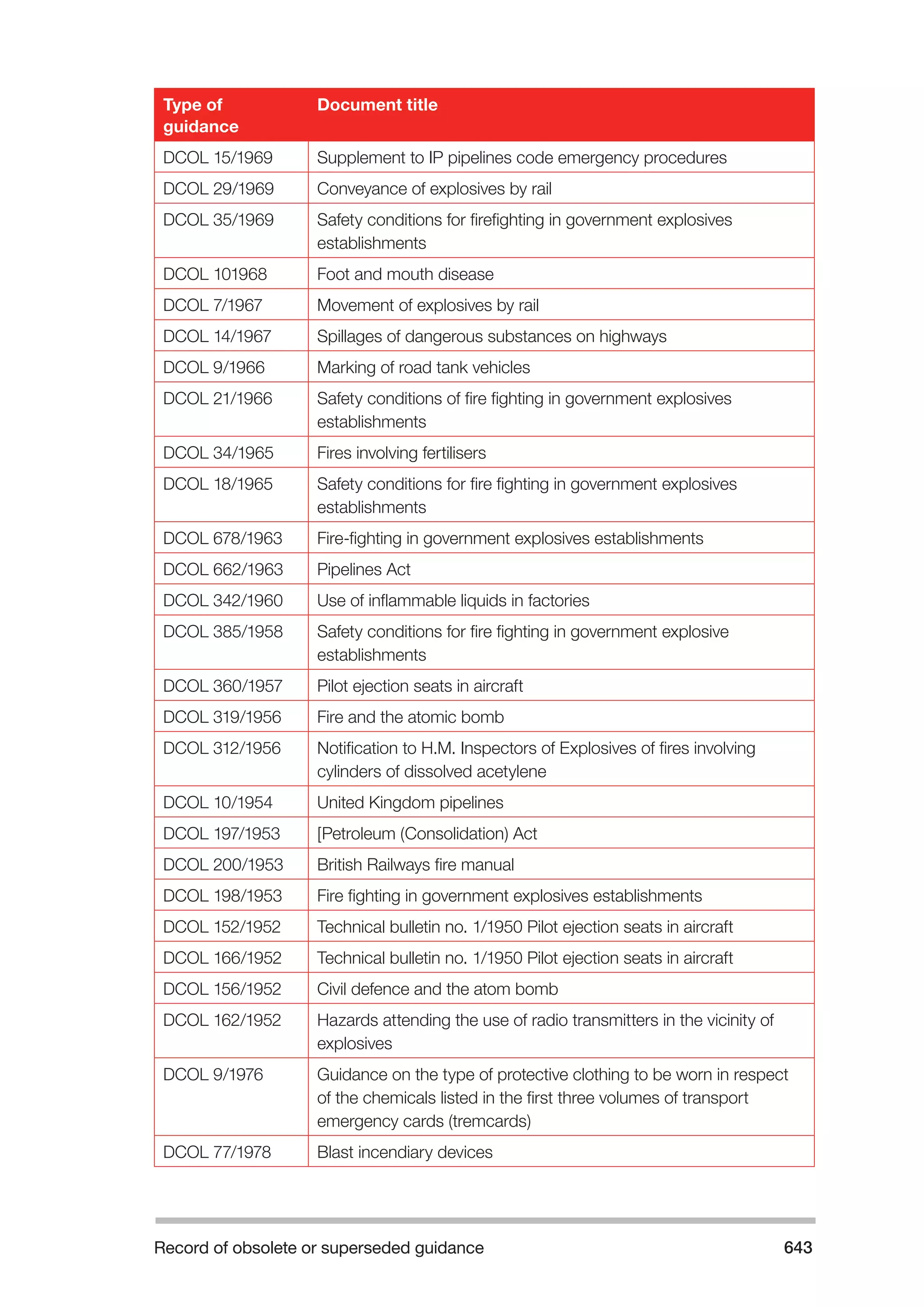

![Fire and Rescue Service Operational Guidance – Incidents 434 involving hazardous materials

solids, liquids or gases. Virtually all non-metal chlorides, fluorides and bromides

are corrosive along with some metal chlorides, notably aluminium and ferric [iron

III].

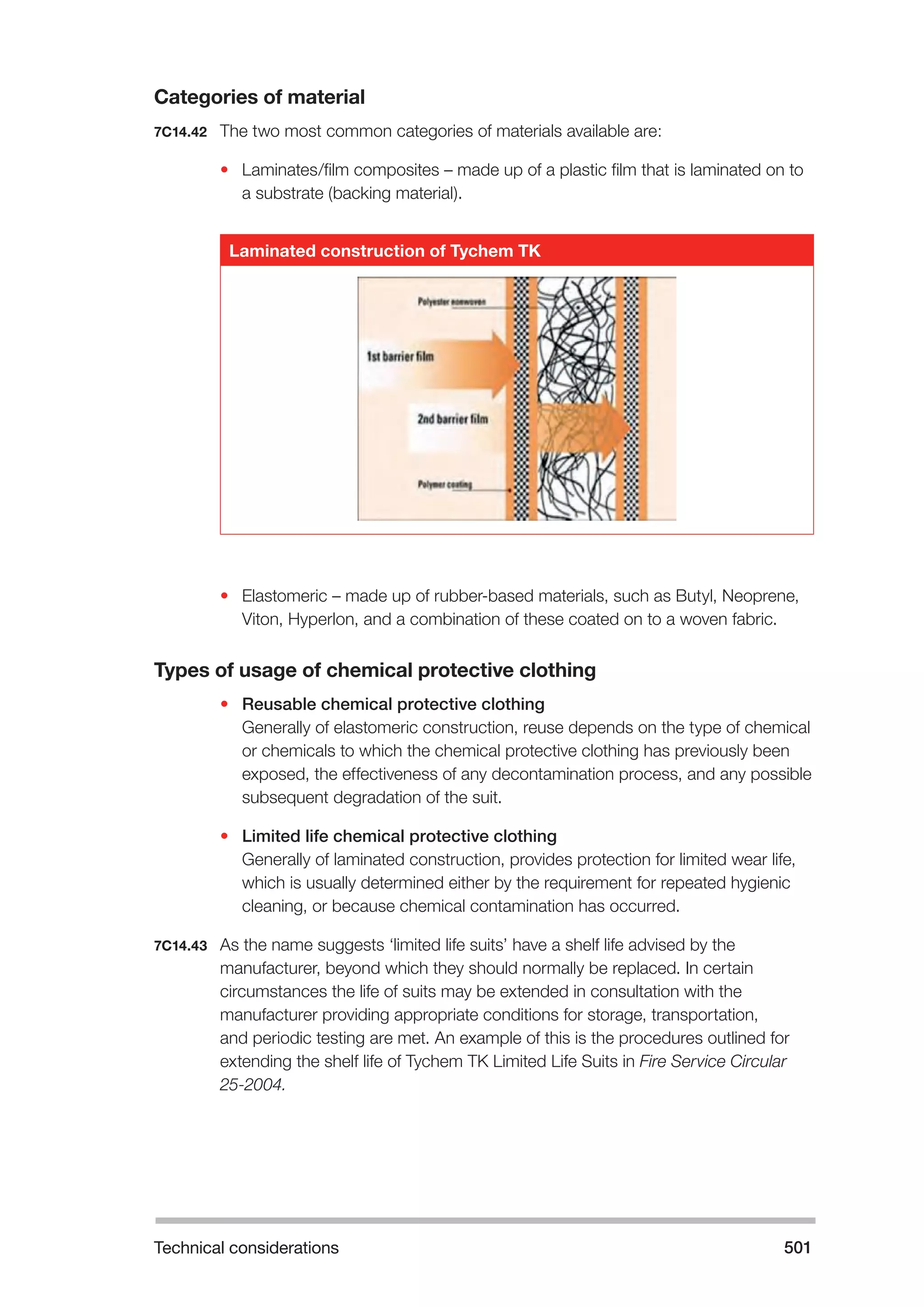

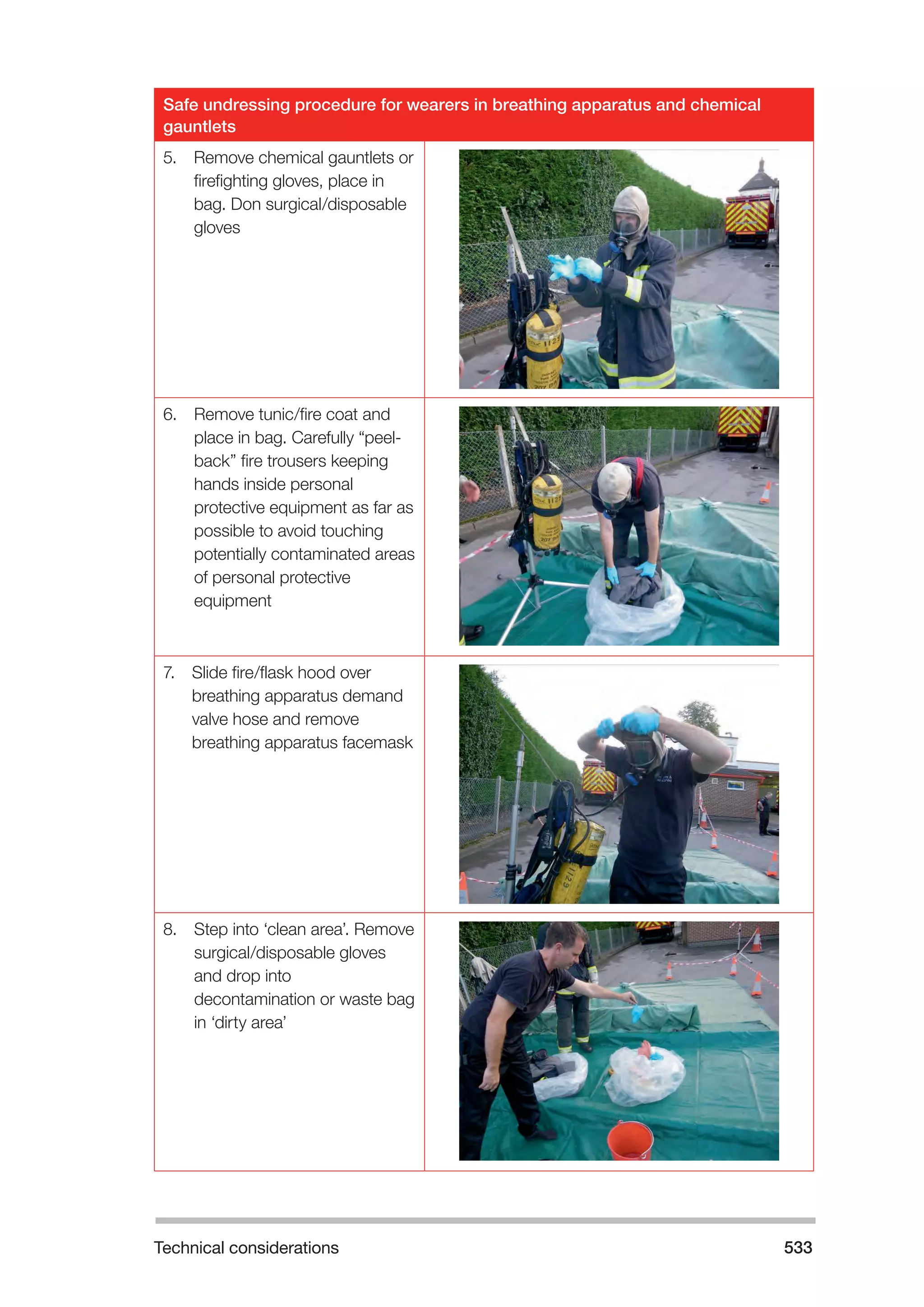

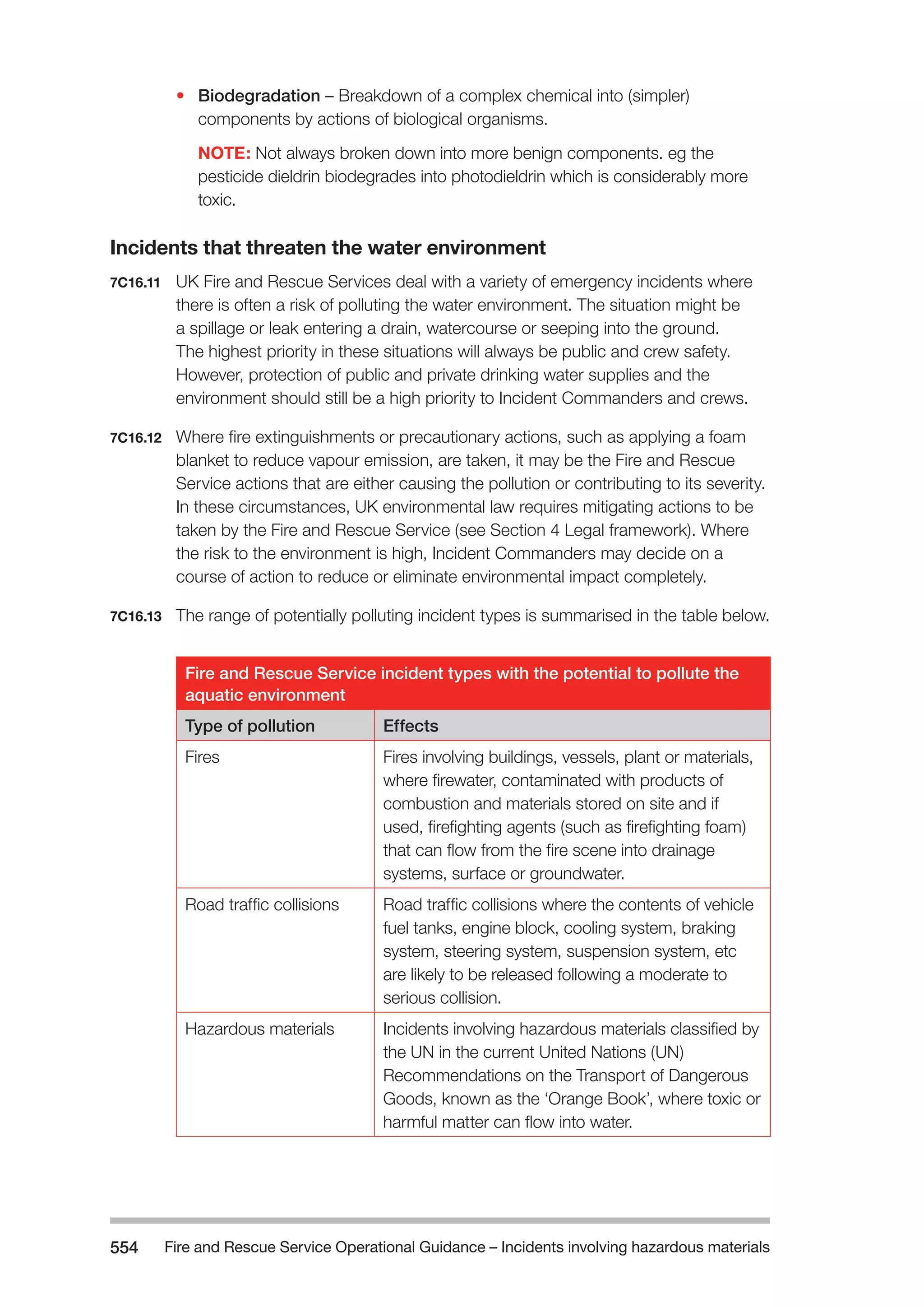

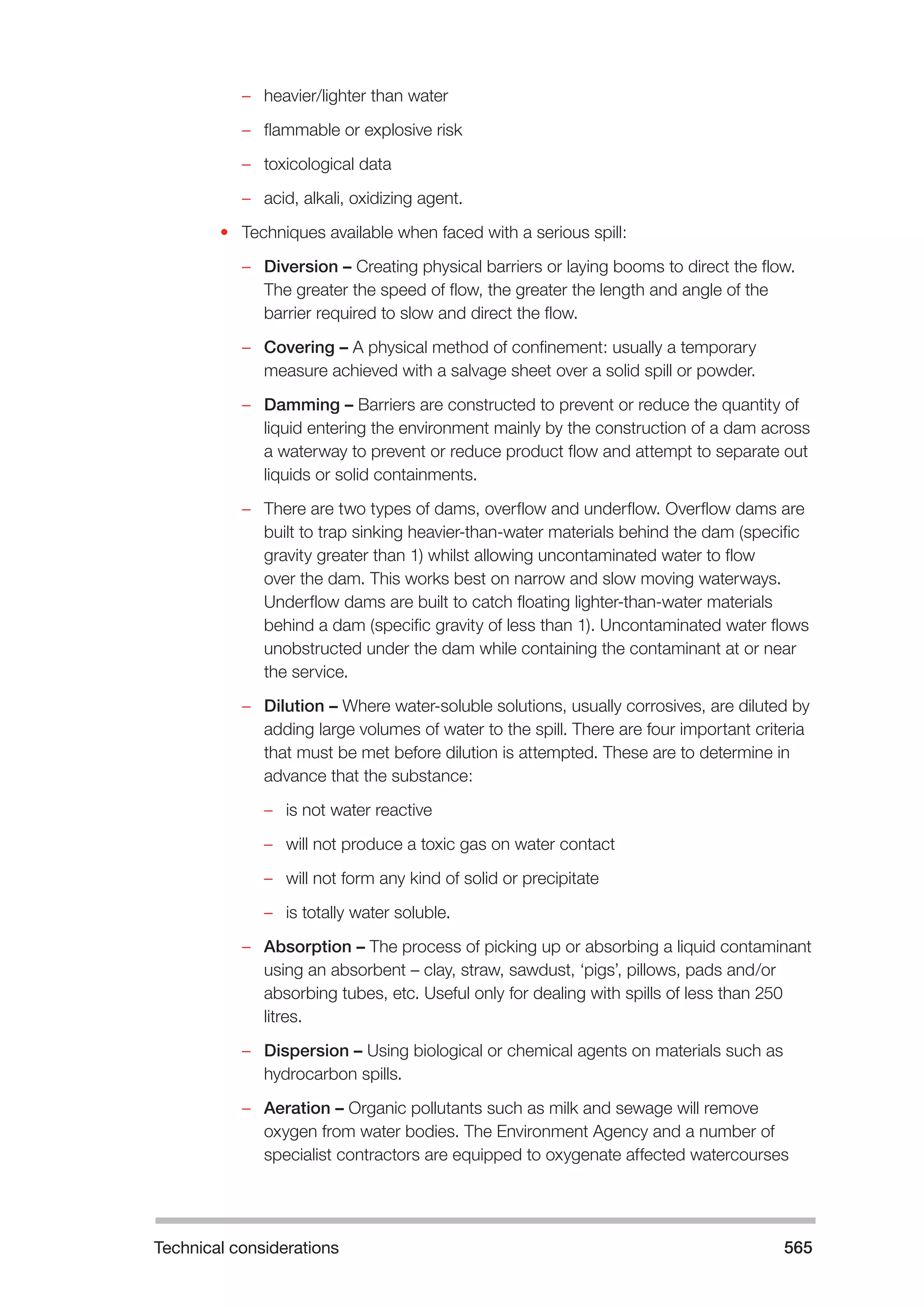

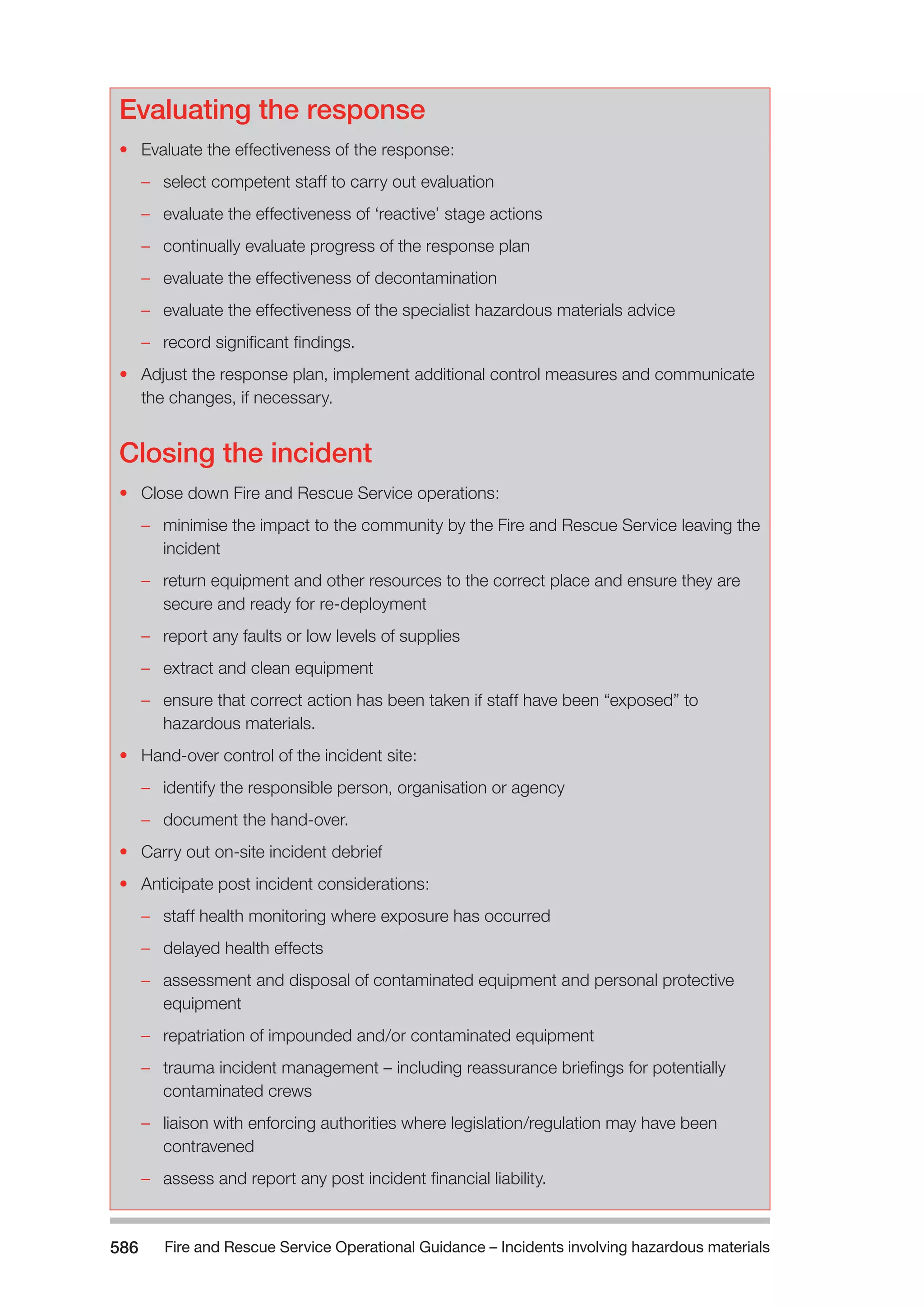

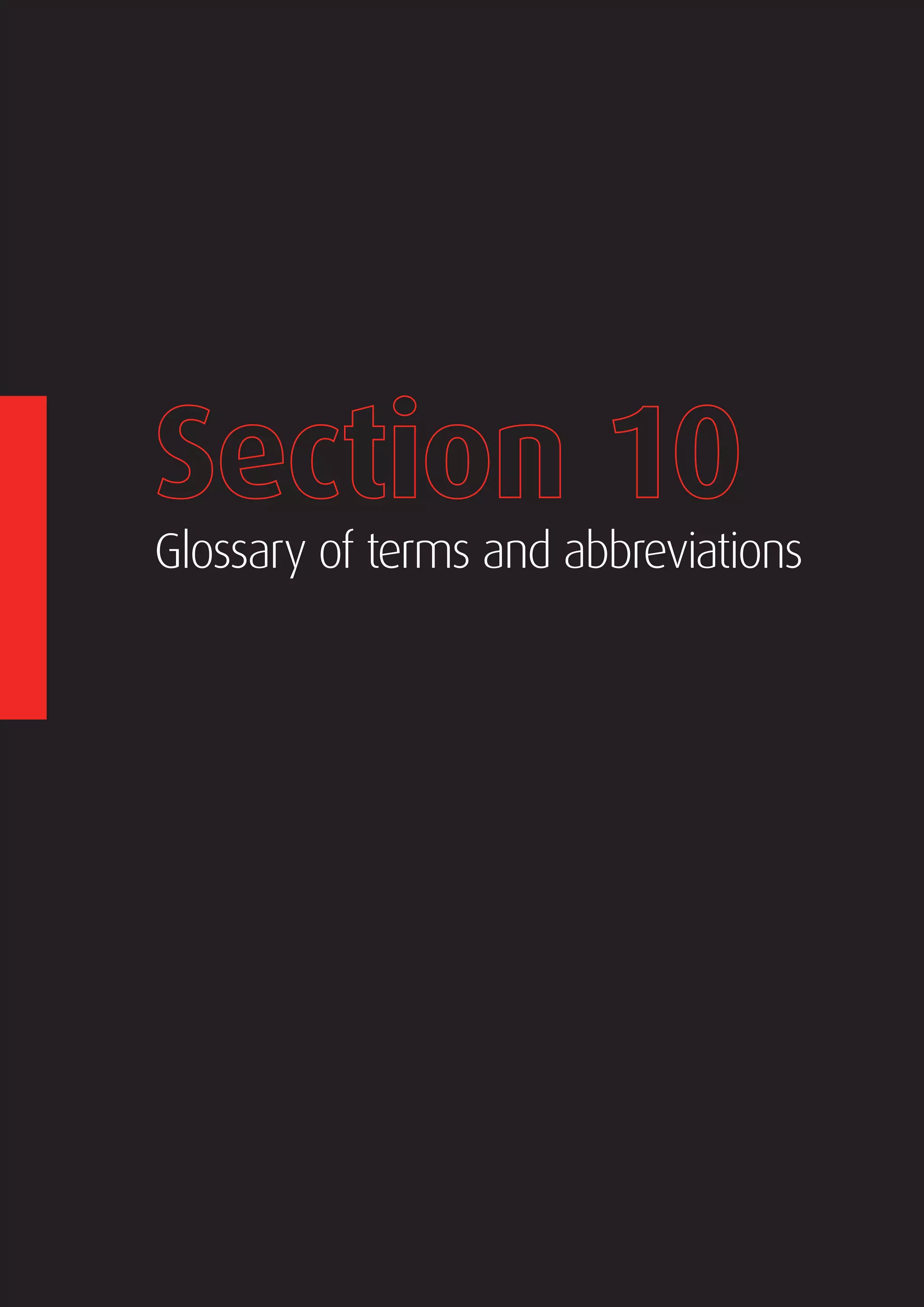

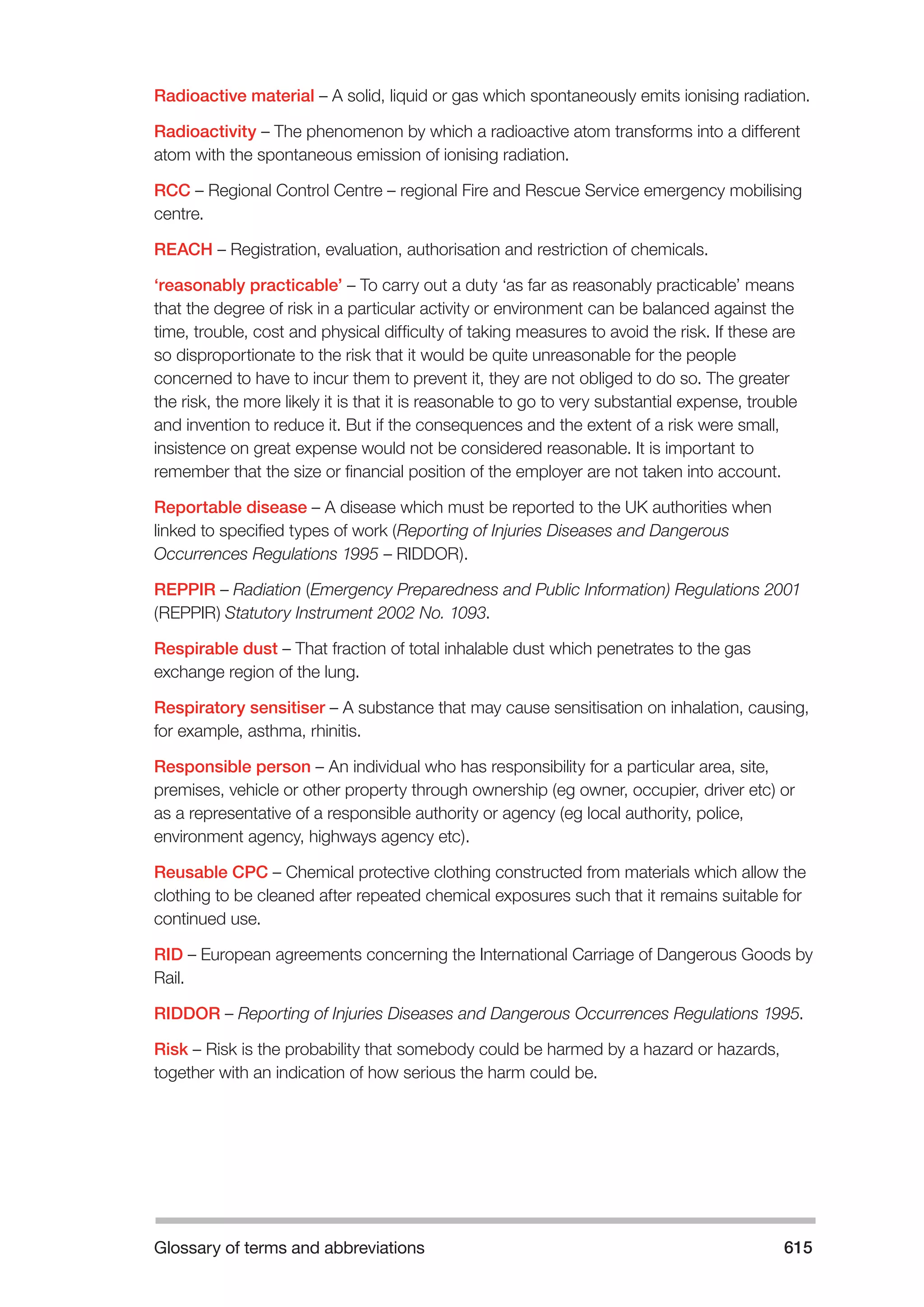

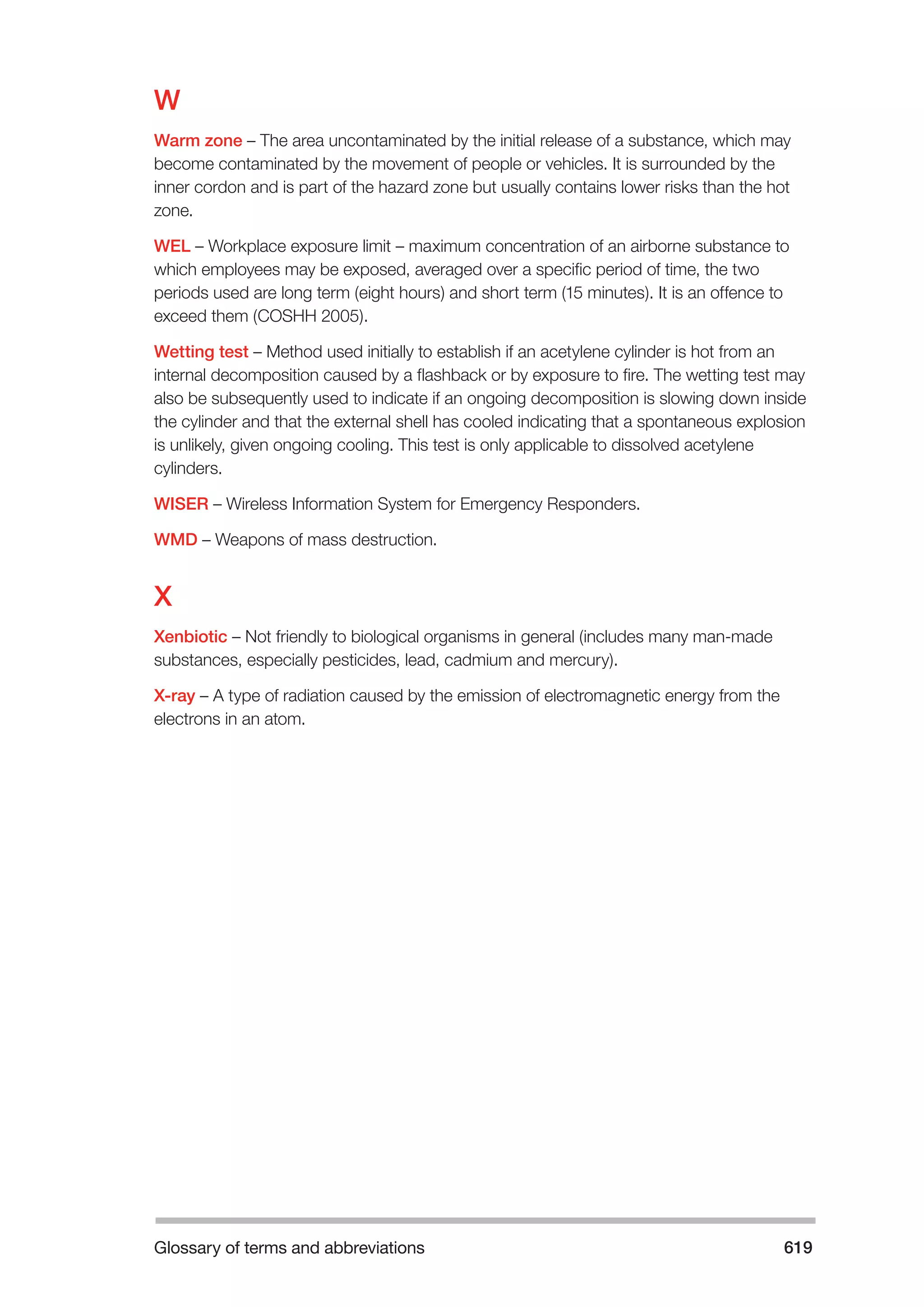

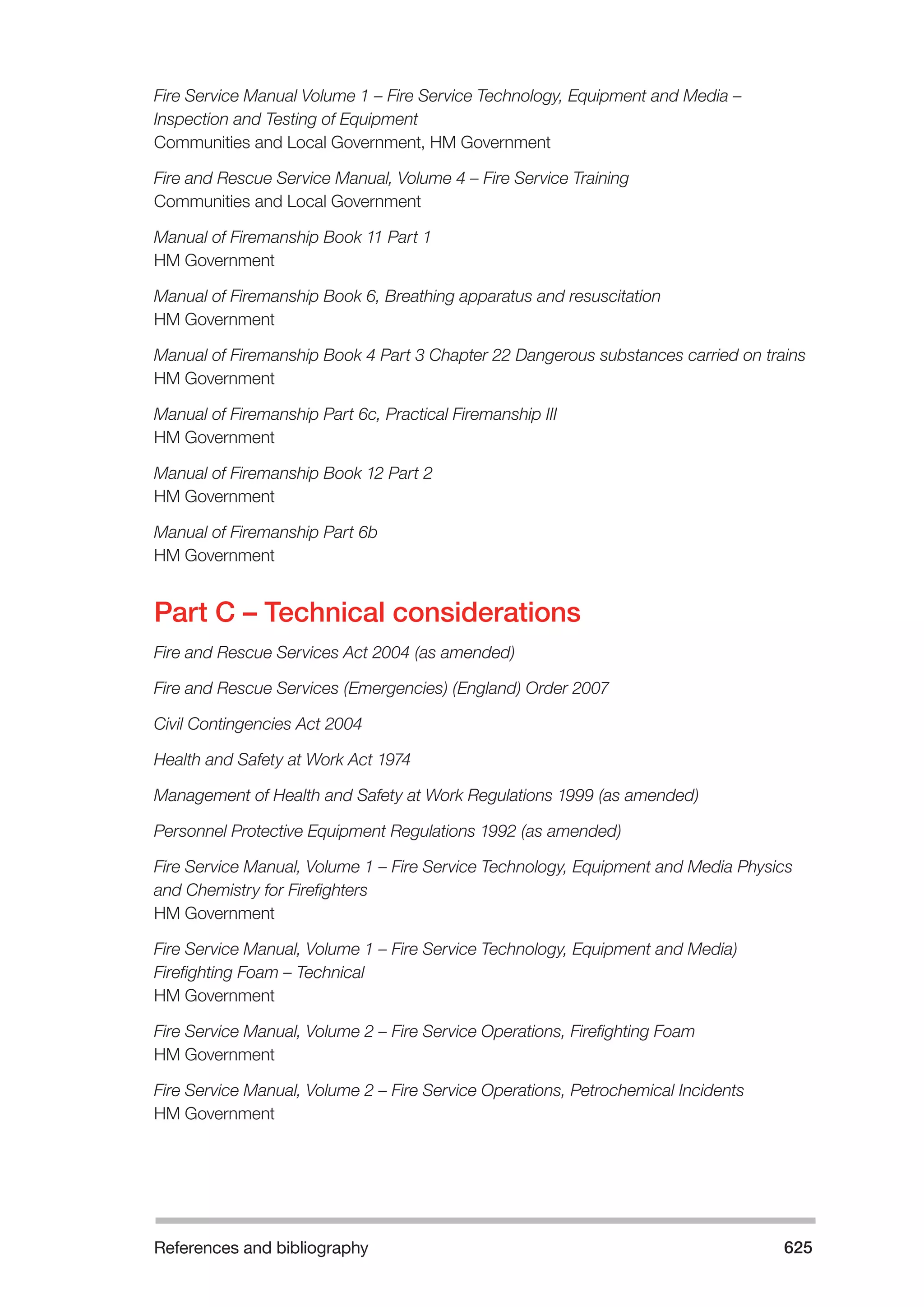

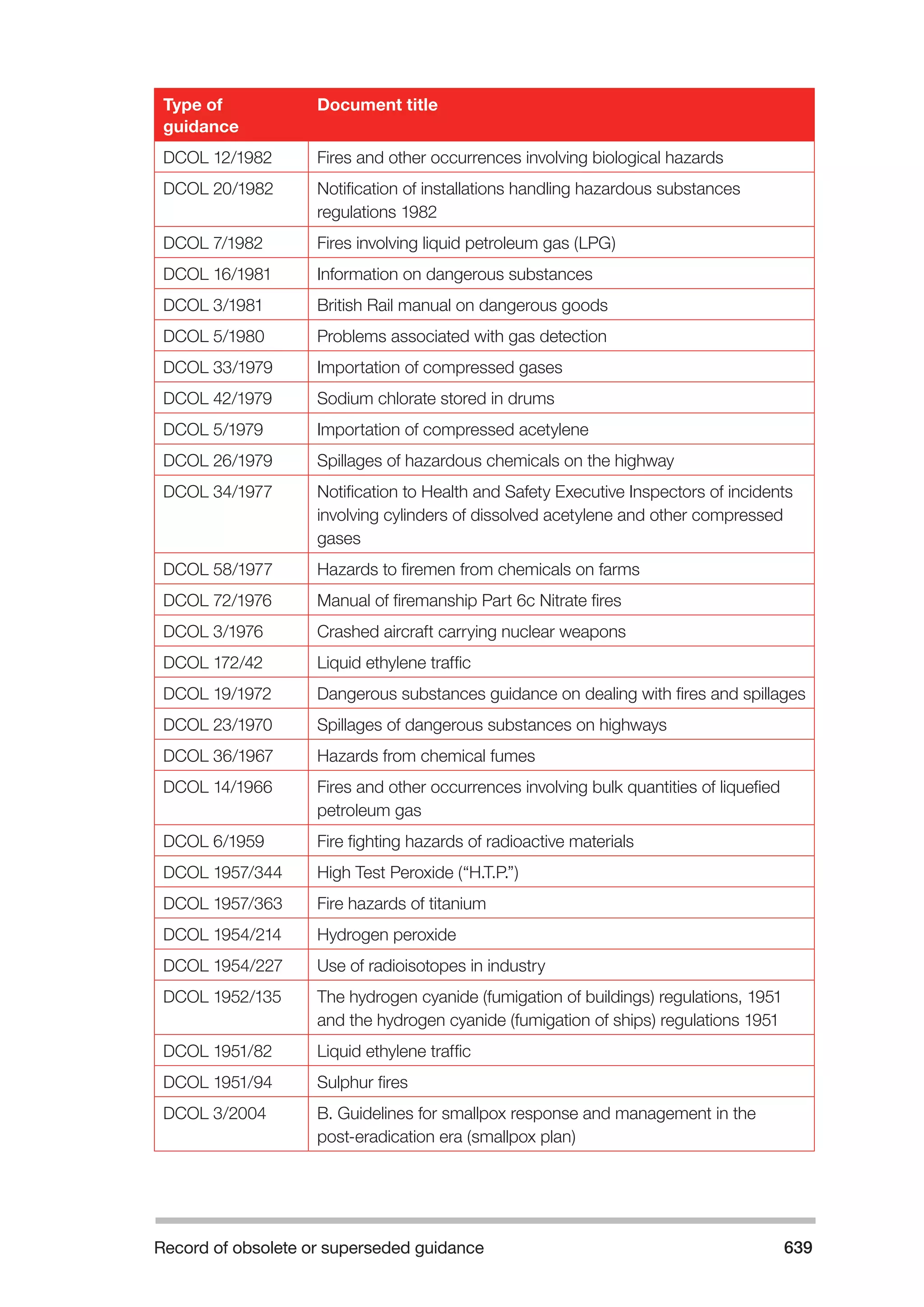

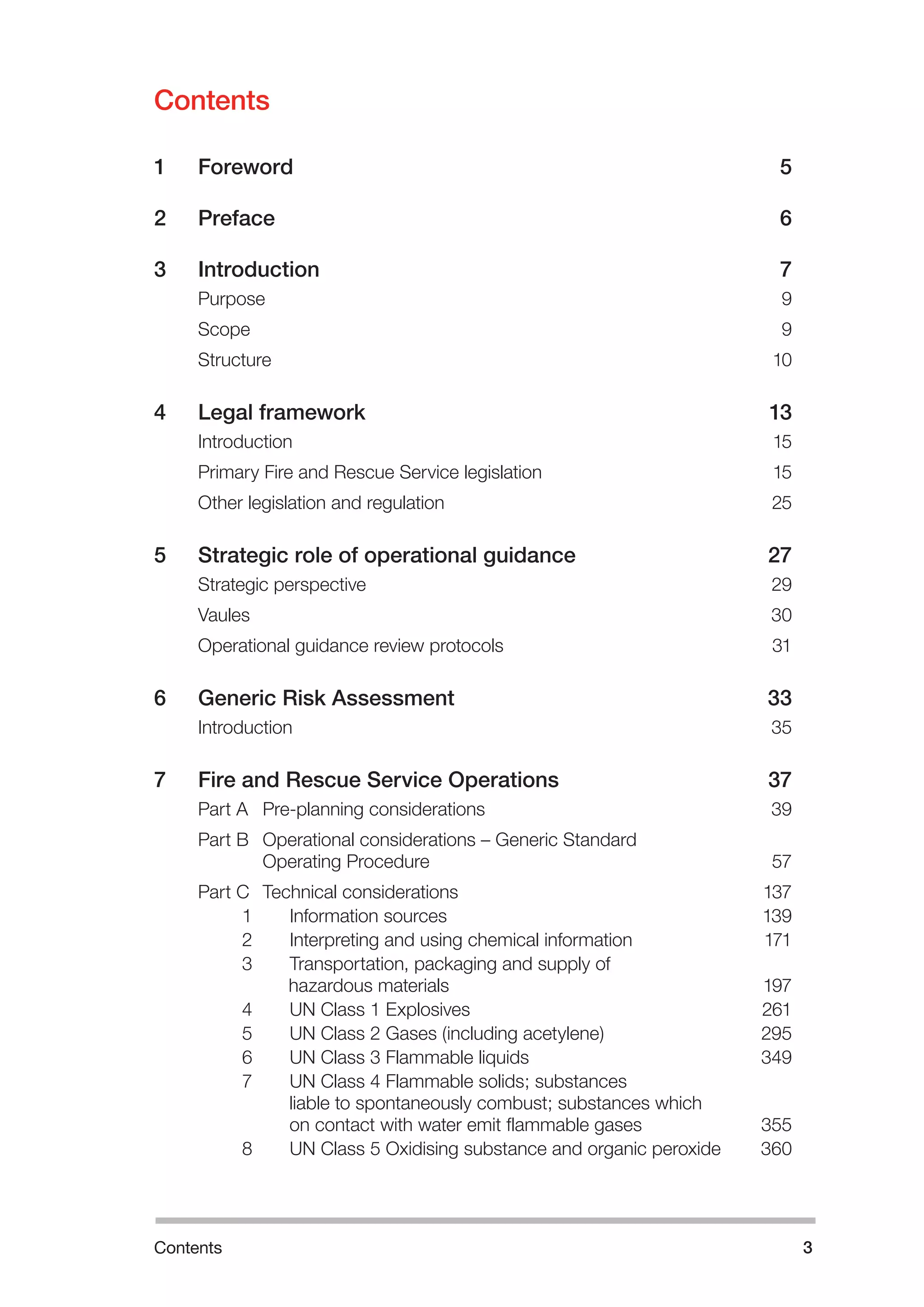

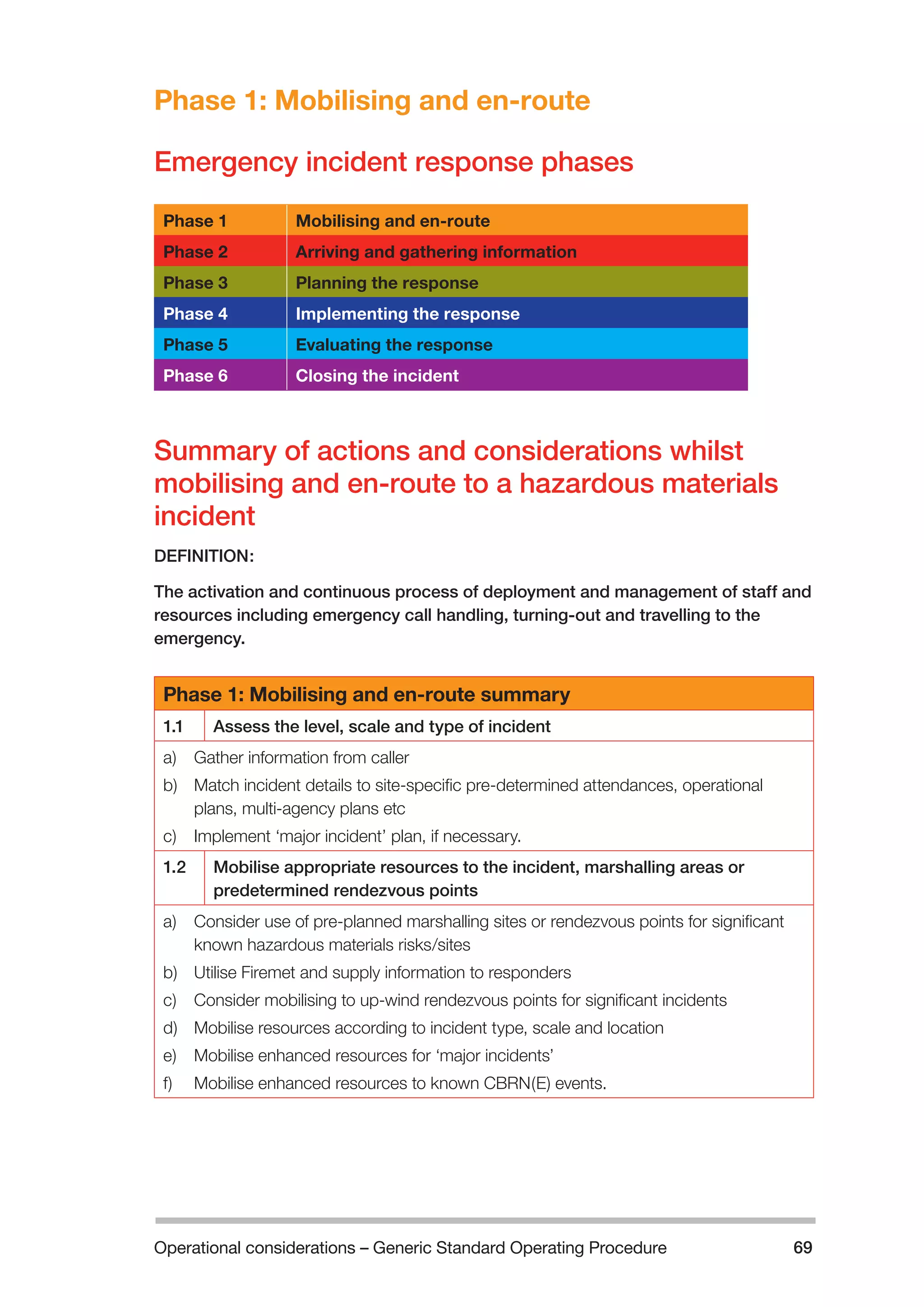

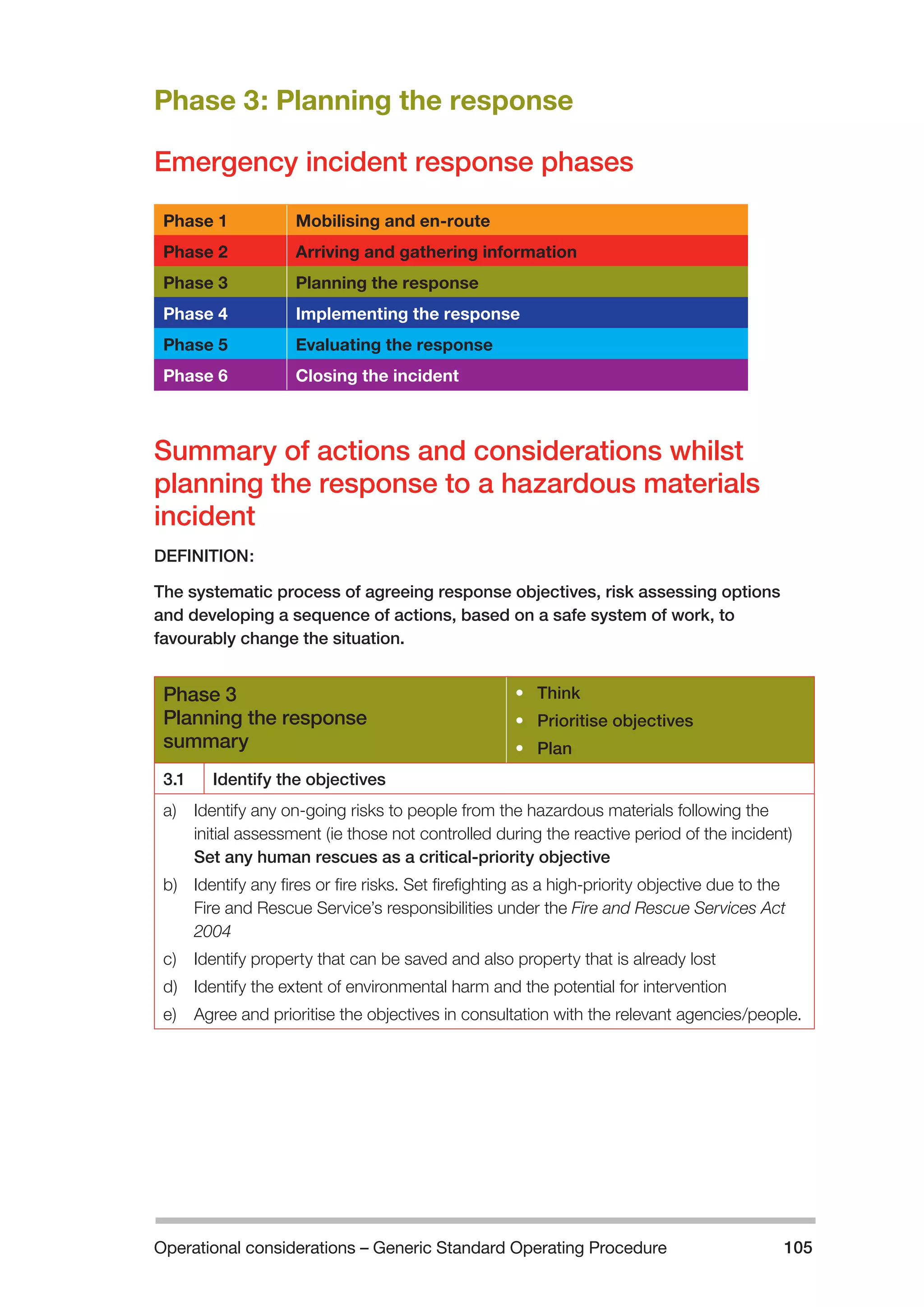

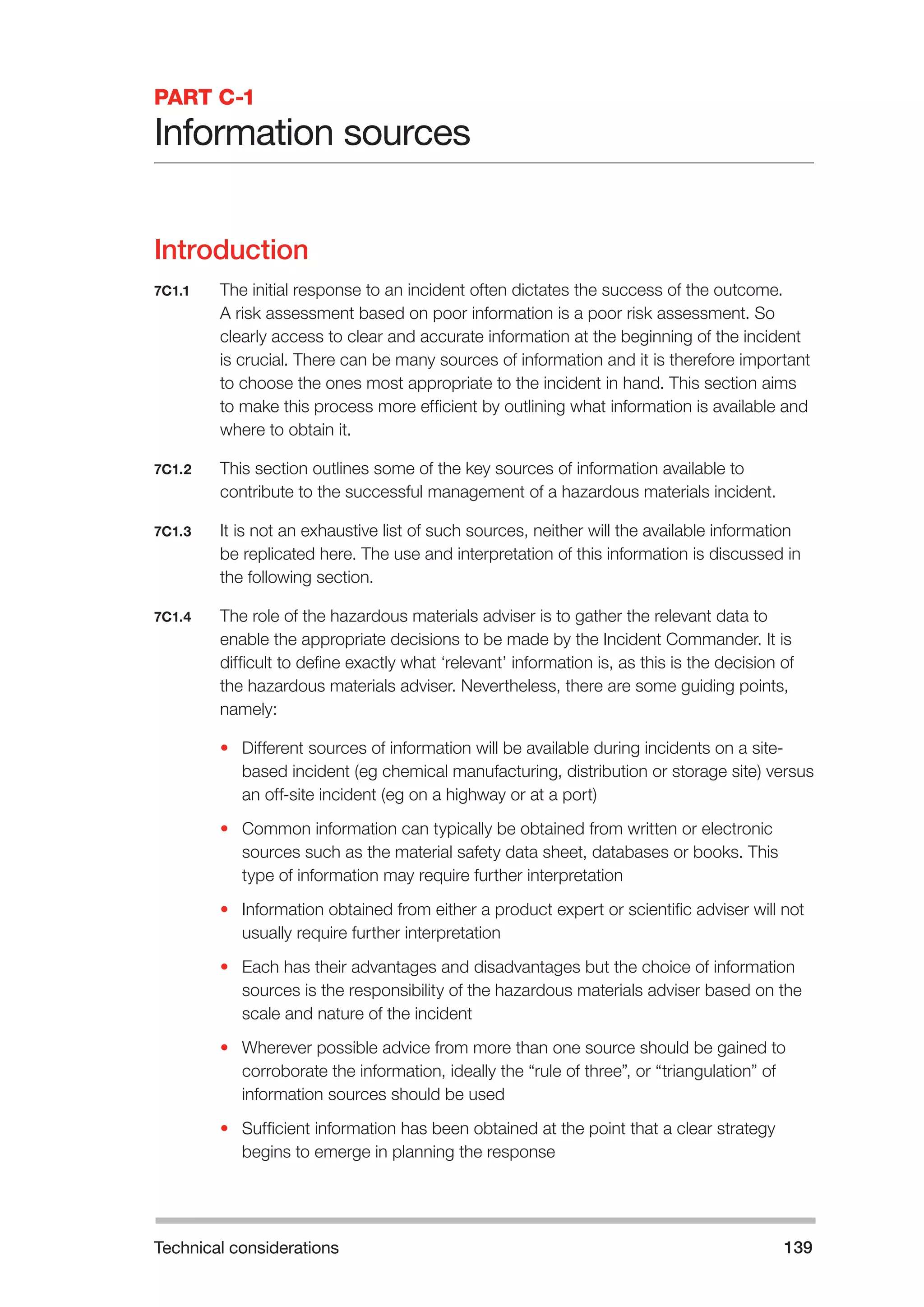

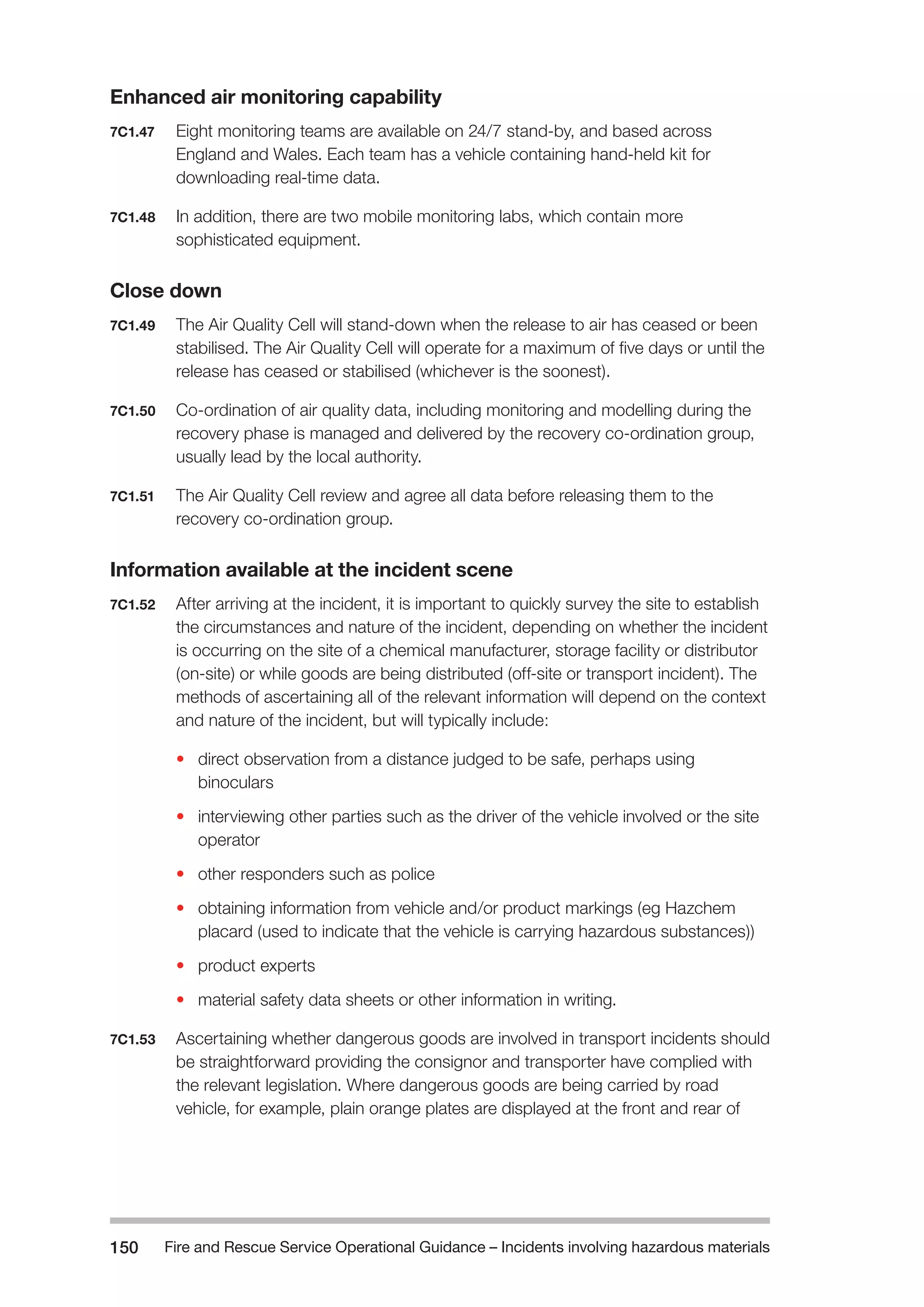

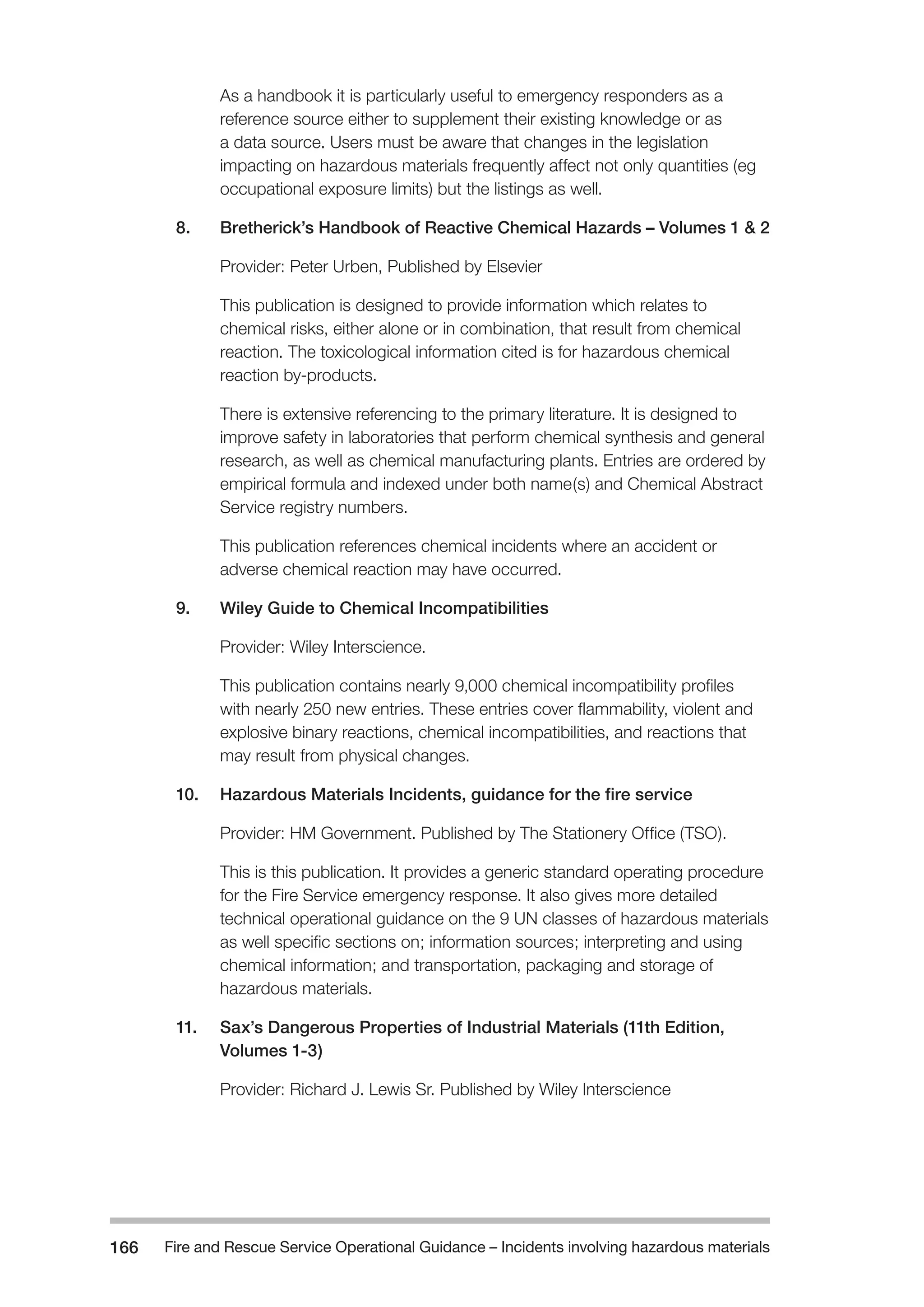

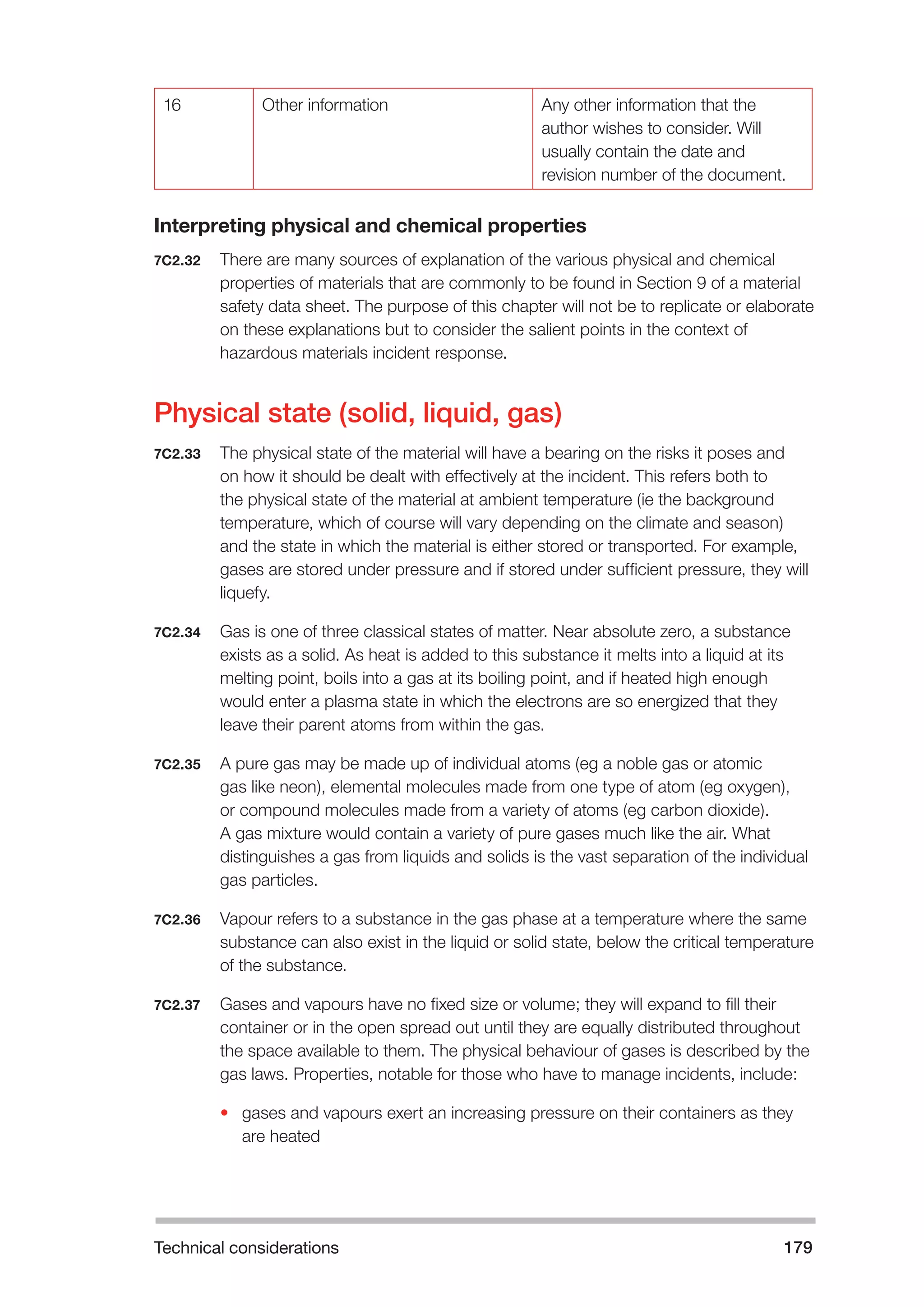

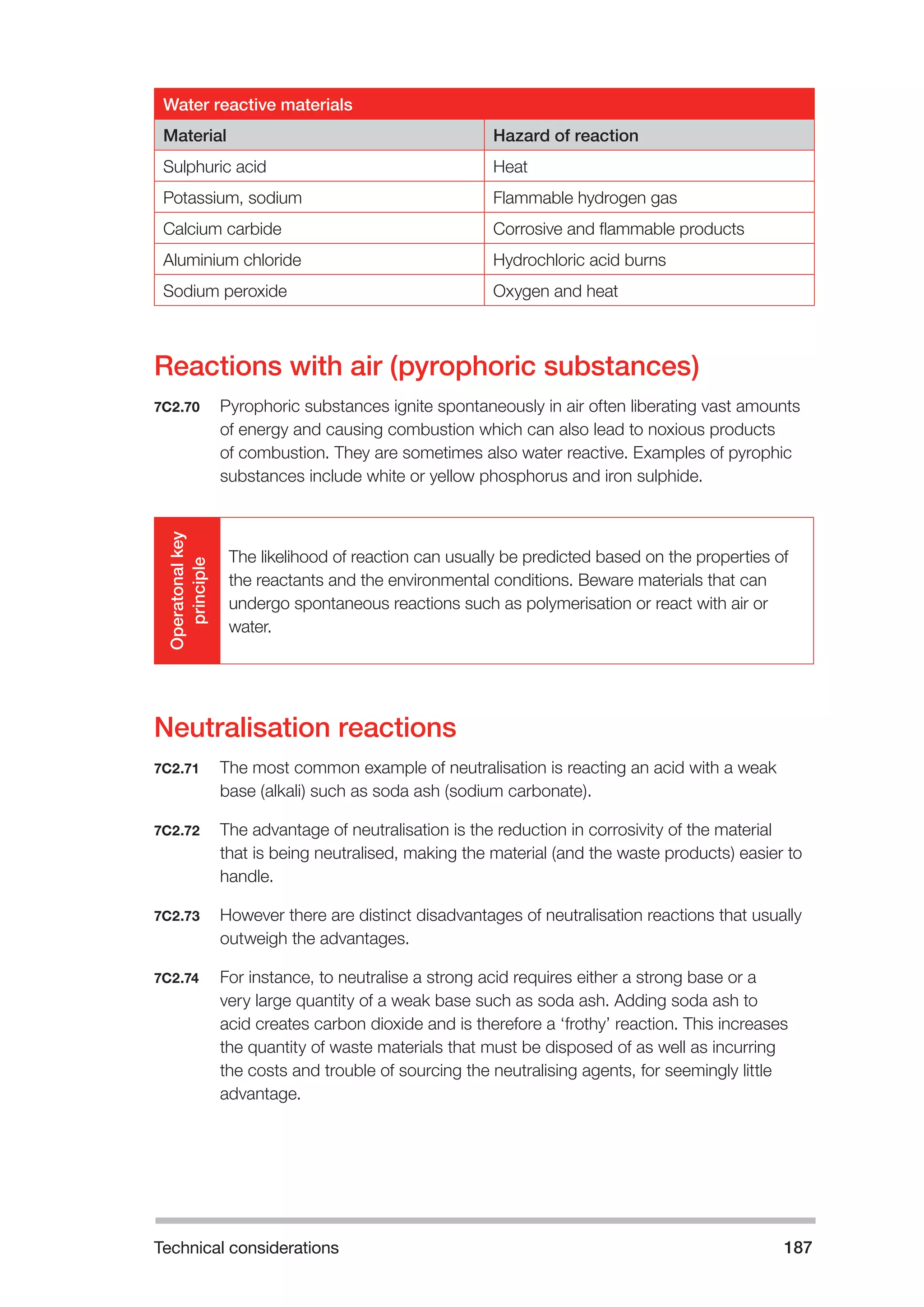

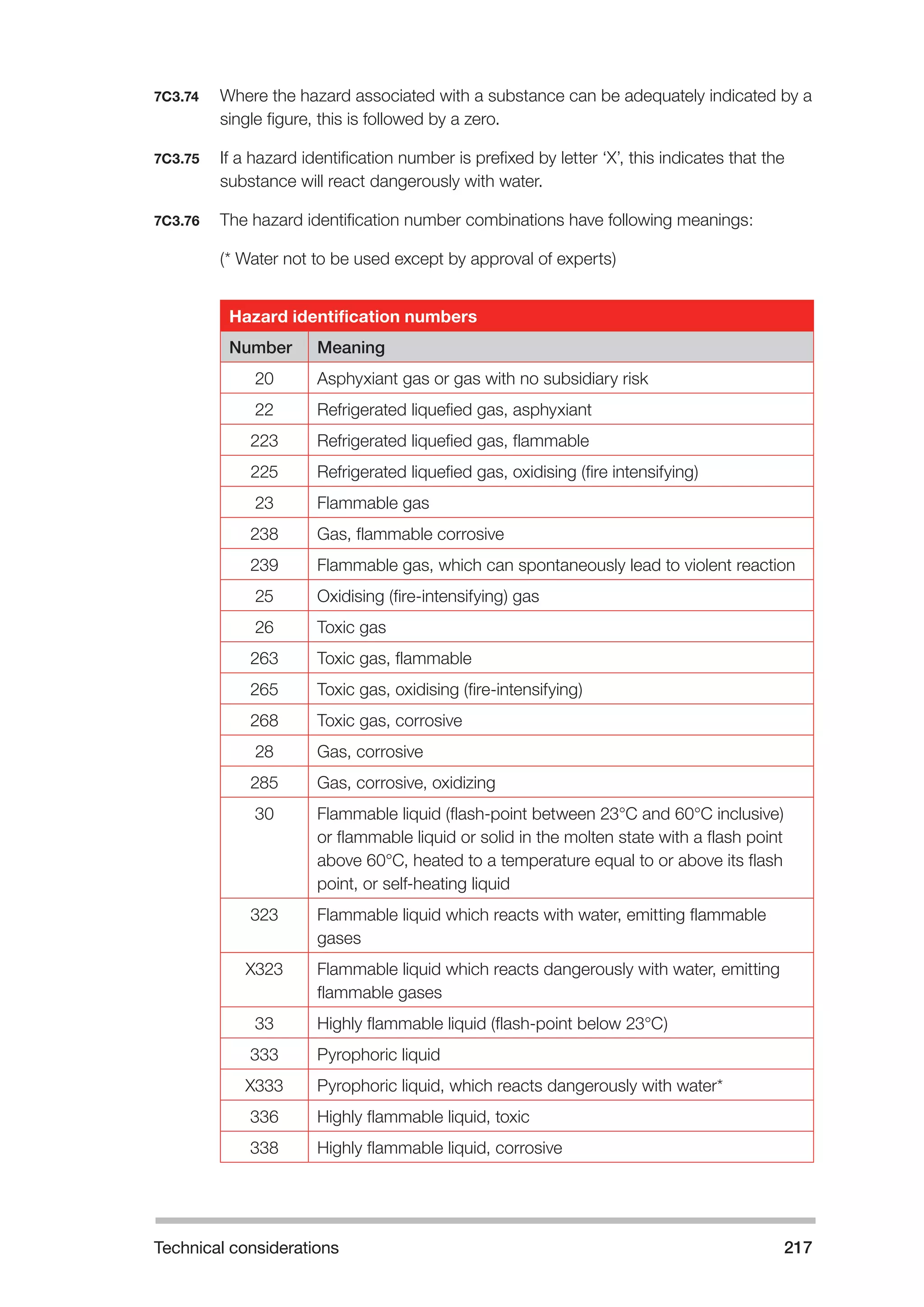

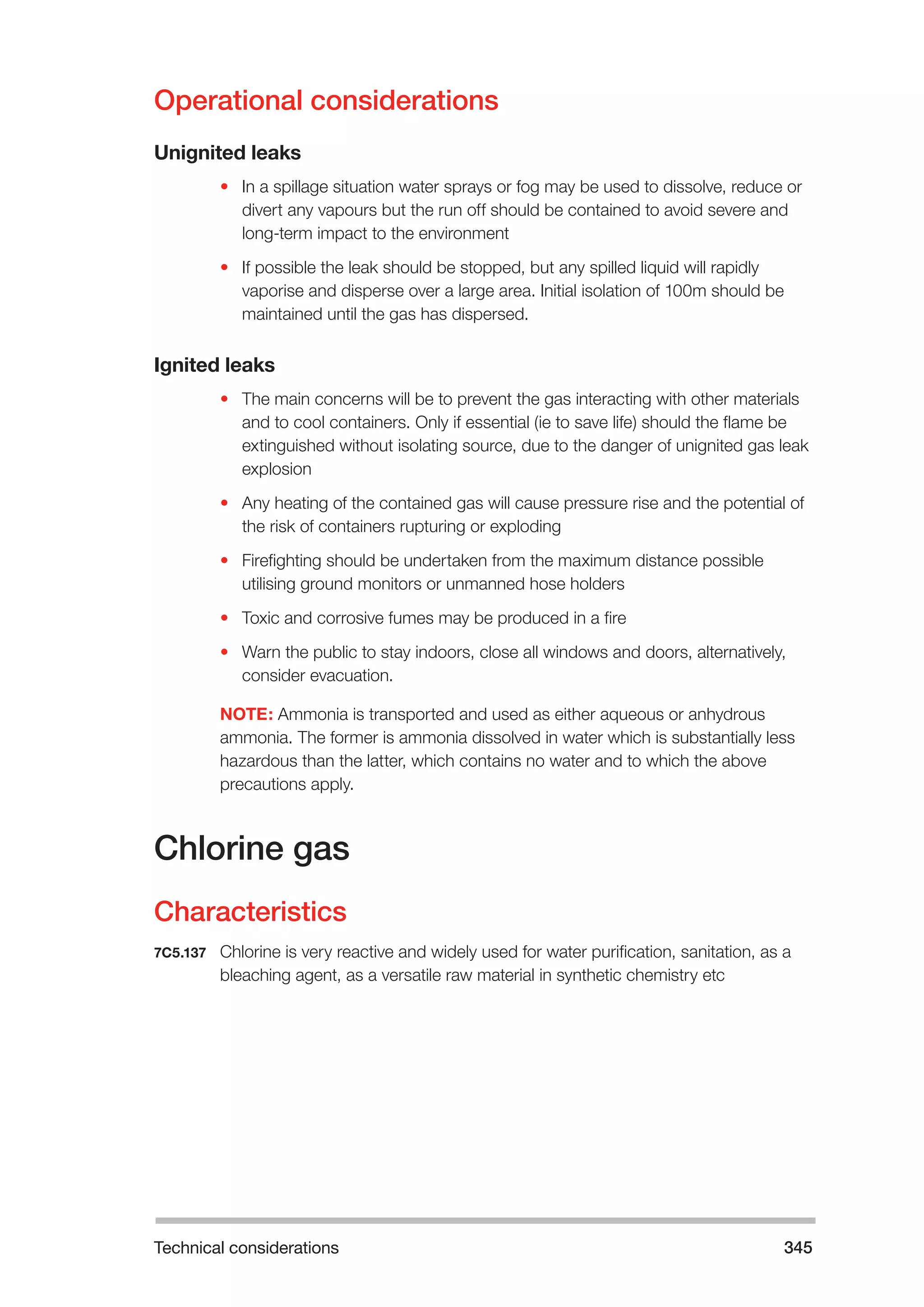

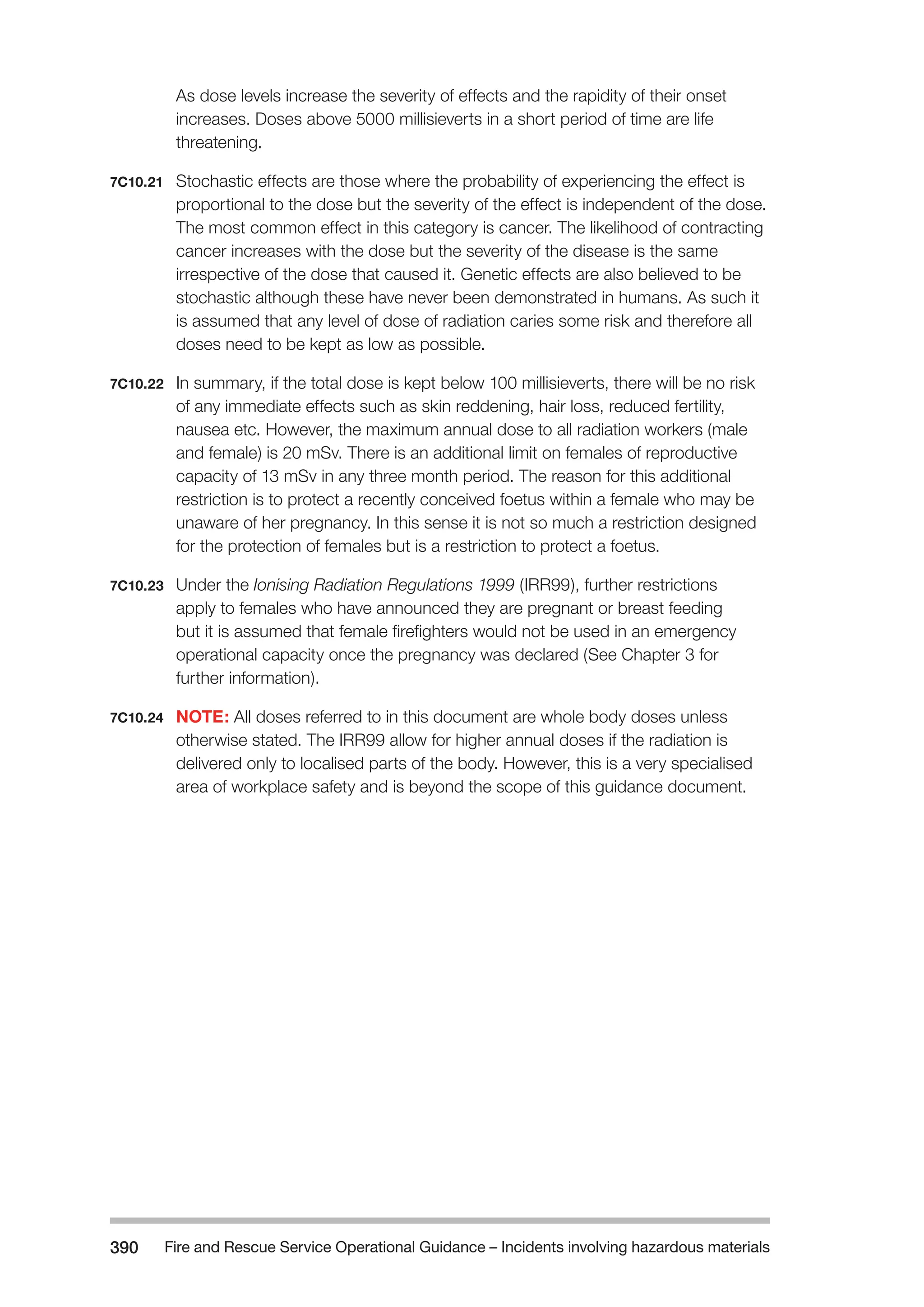

Salts (not common salt, sodium chloride)

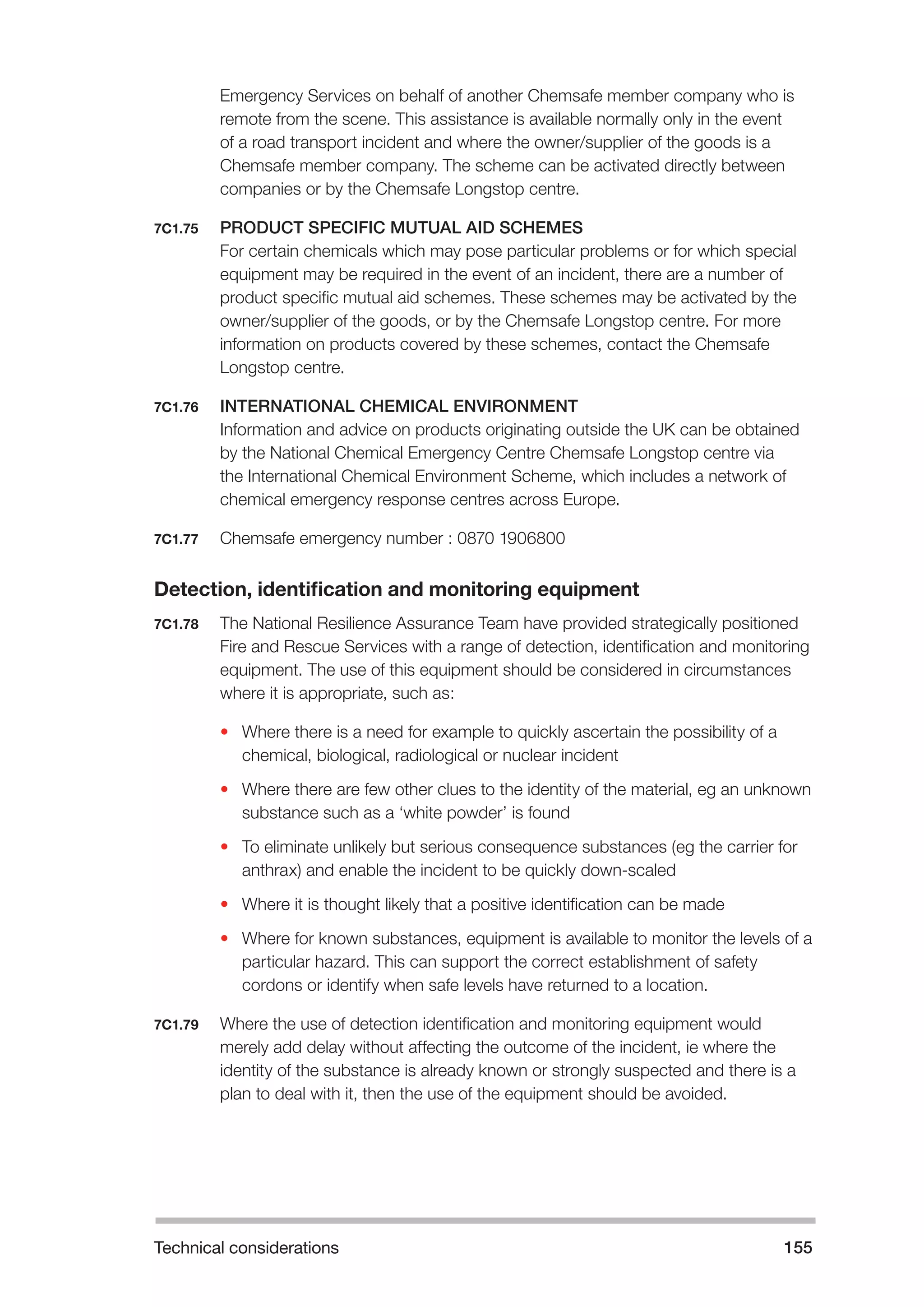

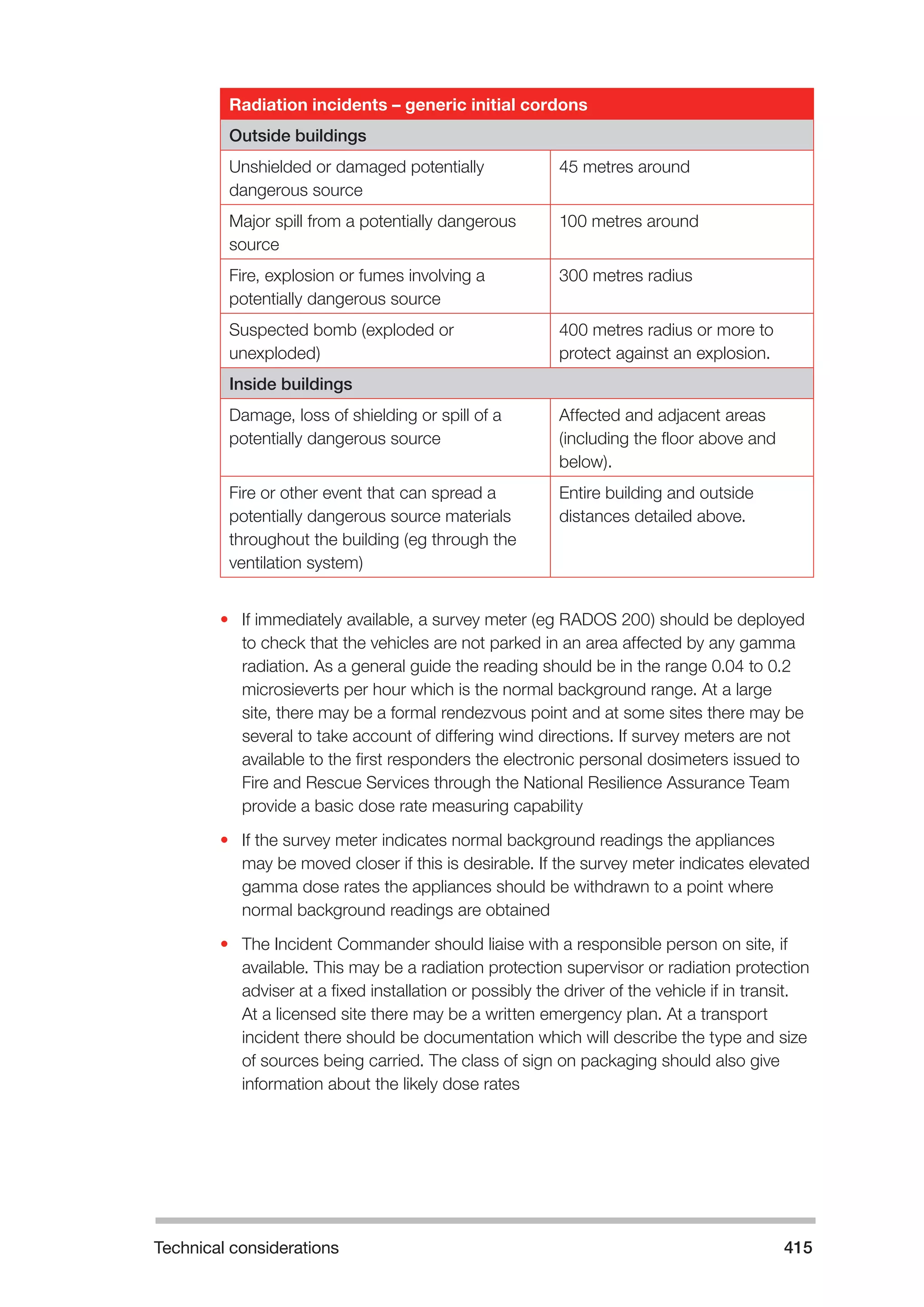

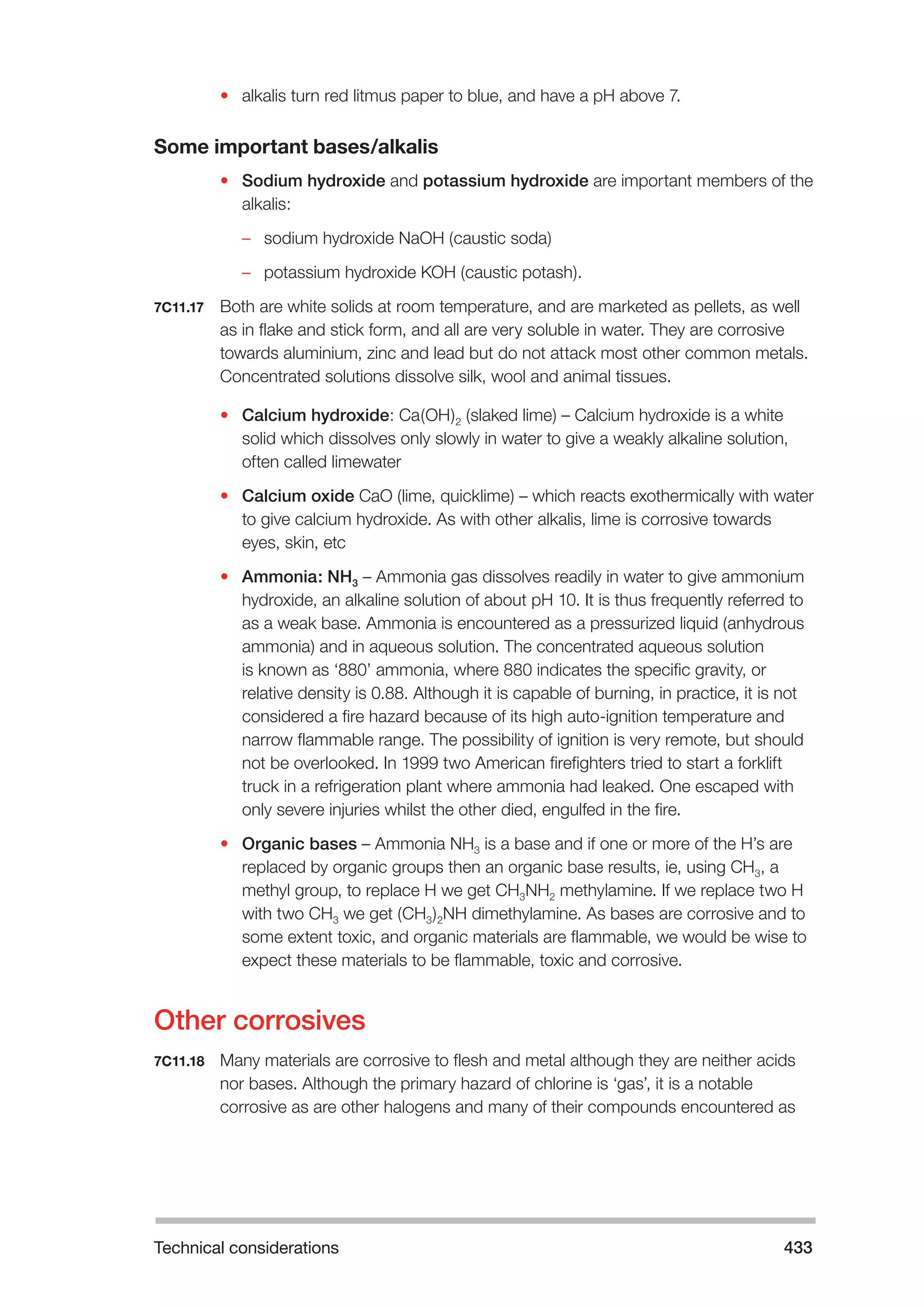

7C11.19 Firefighters should not assume that as a salt is the product of neutralization then

it is safe. Sodium cyanide is a salt but is highly toxic. Sodium peracetate is also a

salt and is explosively unstable. Nitrates are generally good oxidizing substances.

Many chlorides made by the neutralization of hydrochloric acid are corrosive in

their own right. Sometimes the hazards of the parent acid are not exhibited by

the salt, for example, sulphates made by neutralizing sulphuric acid or otherwise

are not water reactive.

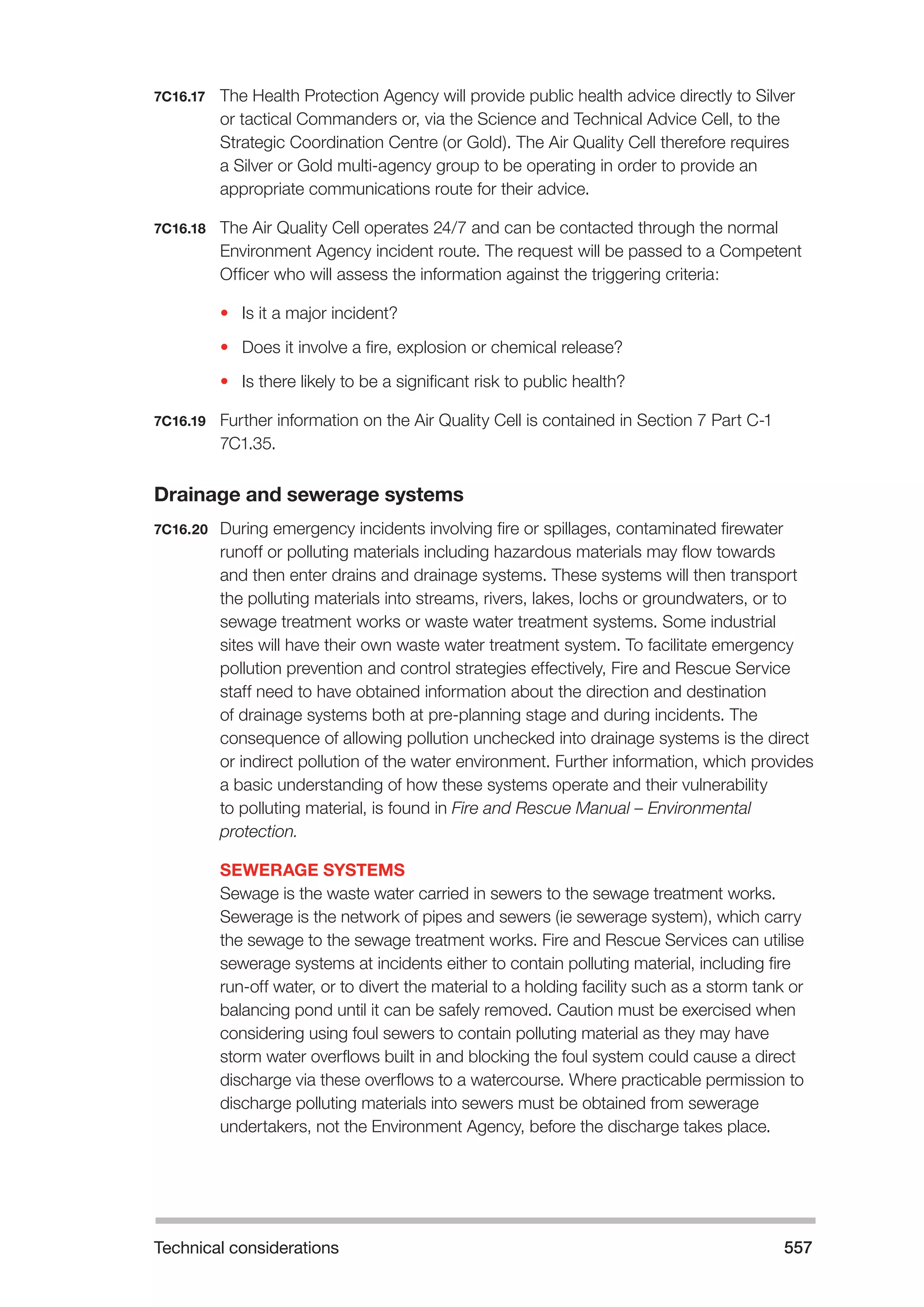

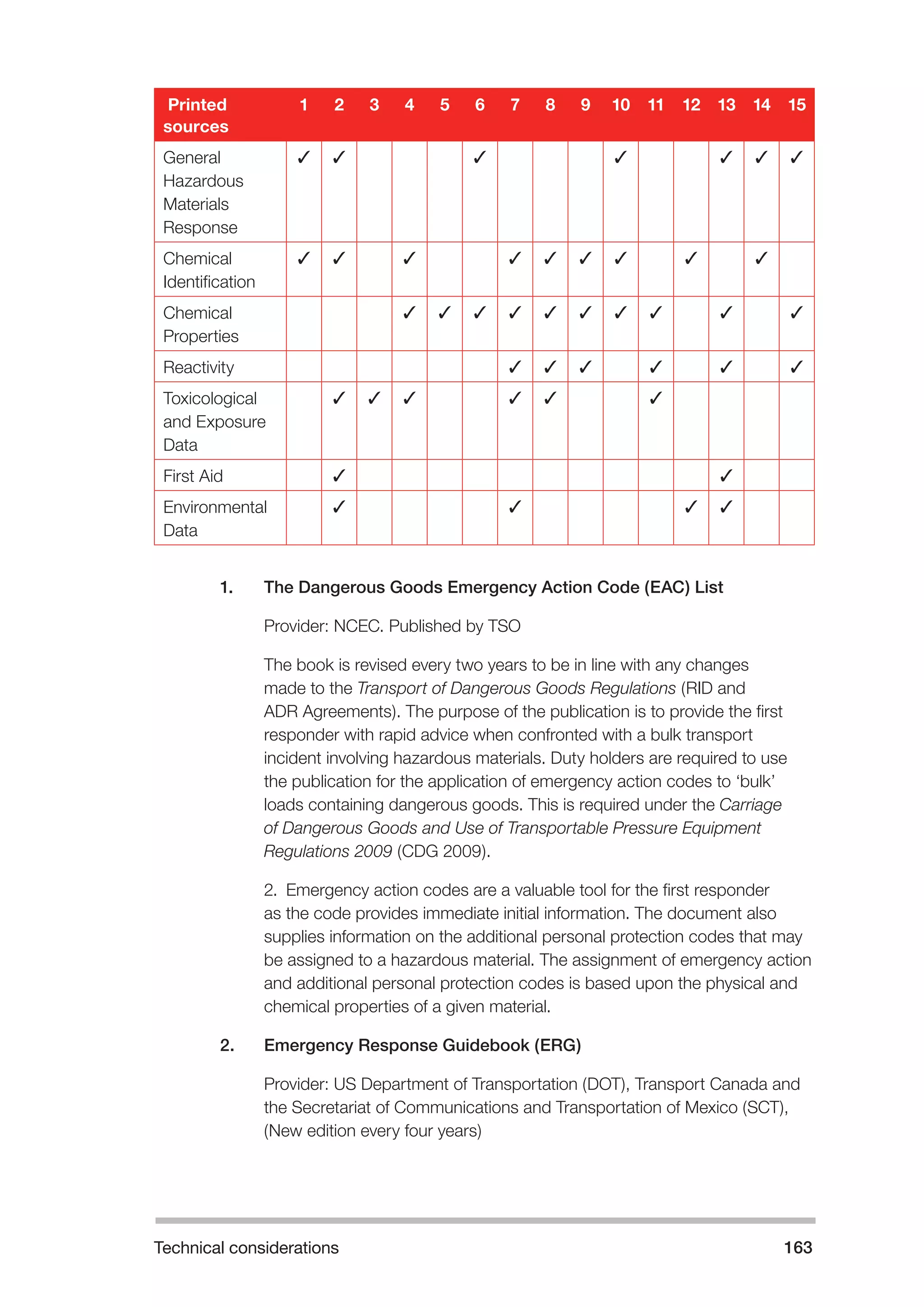

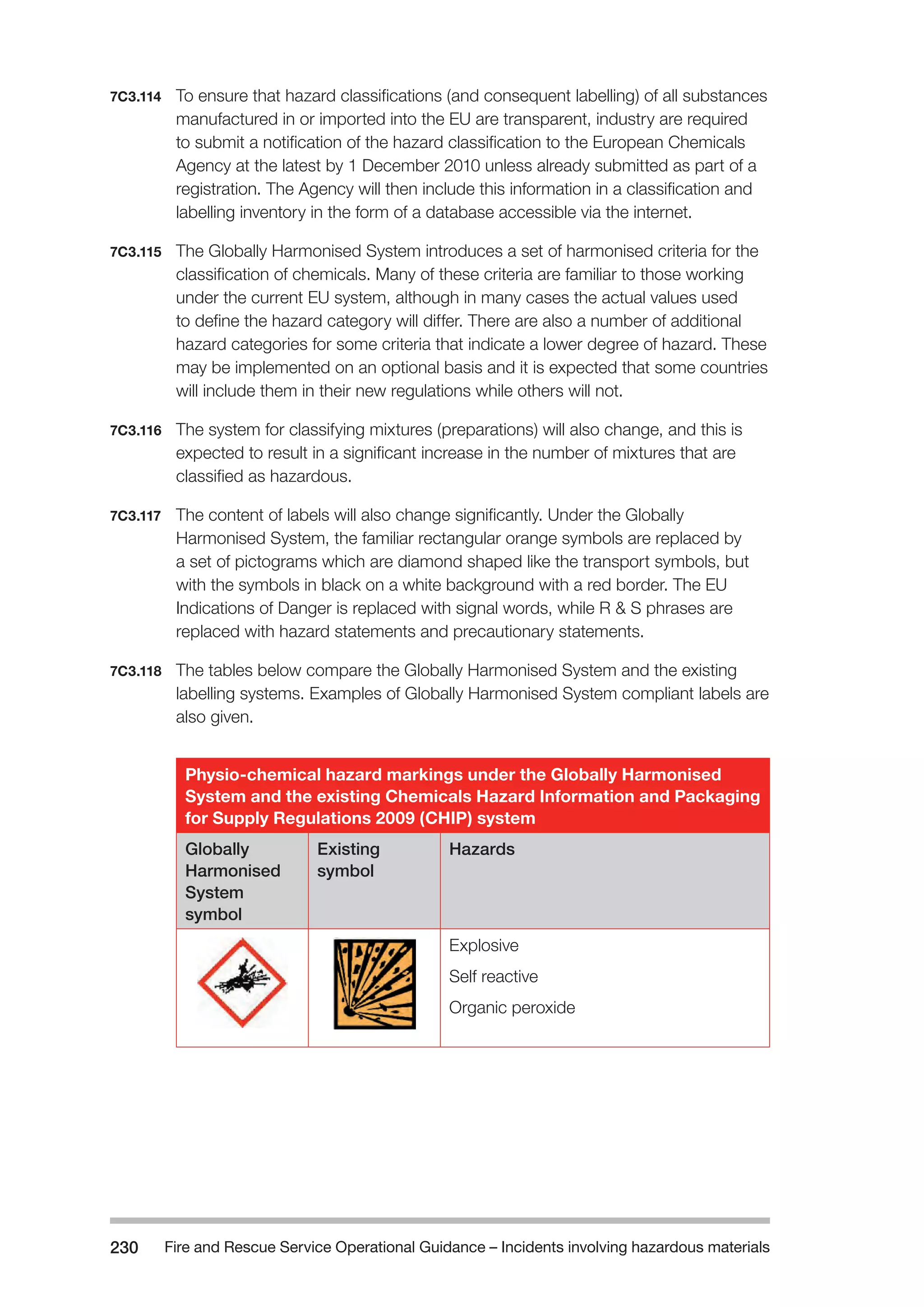

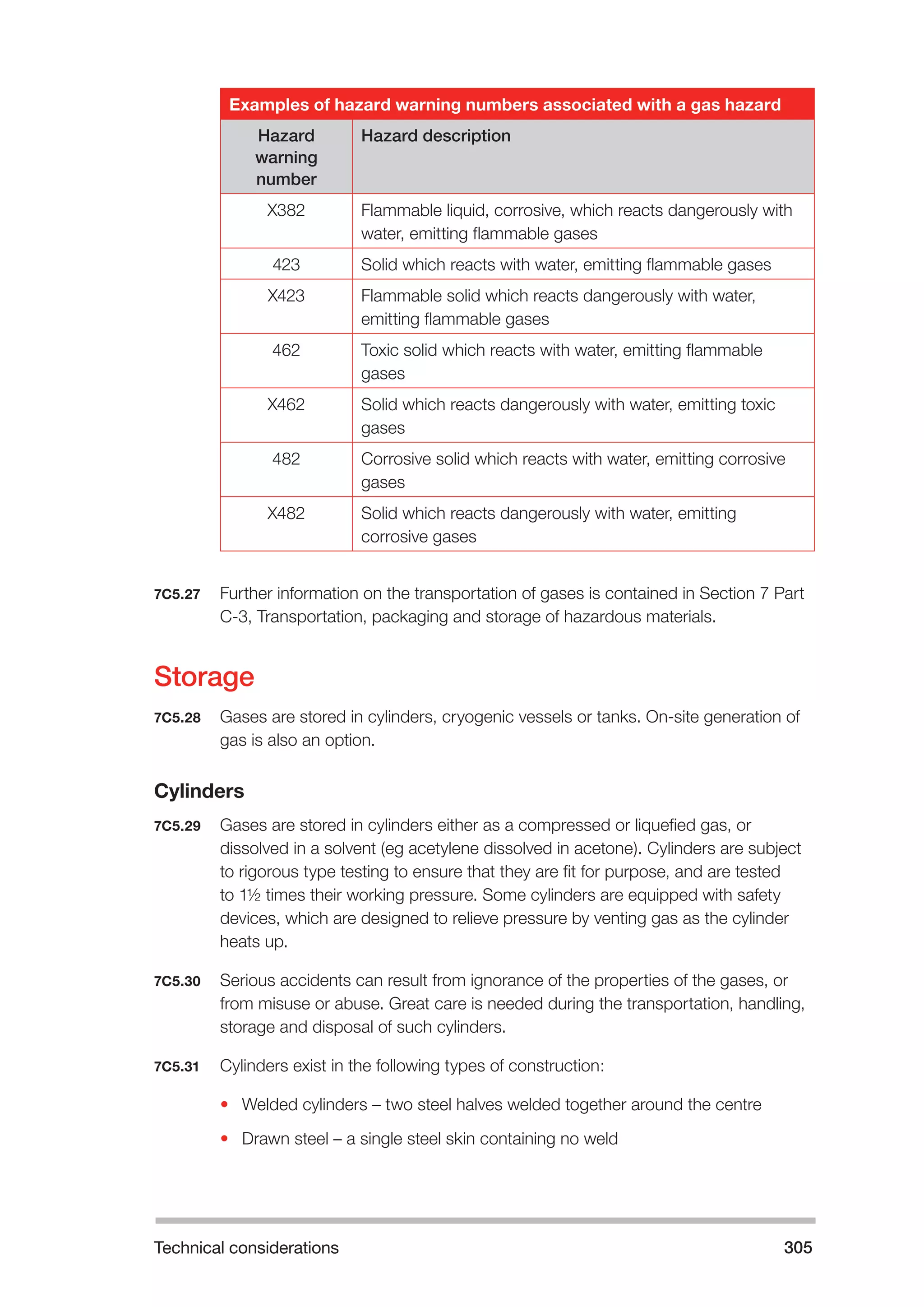

7C11.20 NOTE: Firefighters should understand that whilst neutralisation may remove

the corrosive hazard of the acid or alkali, it might accentuate other hazards and

generate a salt that is itself corrosive or hazardous in some other way. A list of

common salts and the acid from which they were formed is shown below.

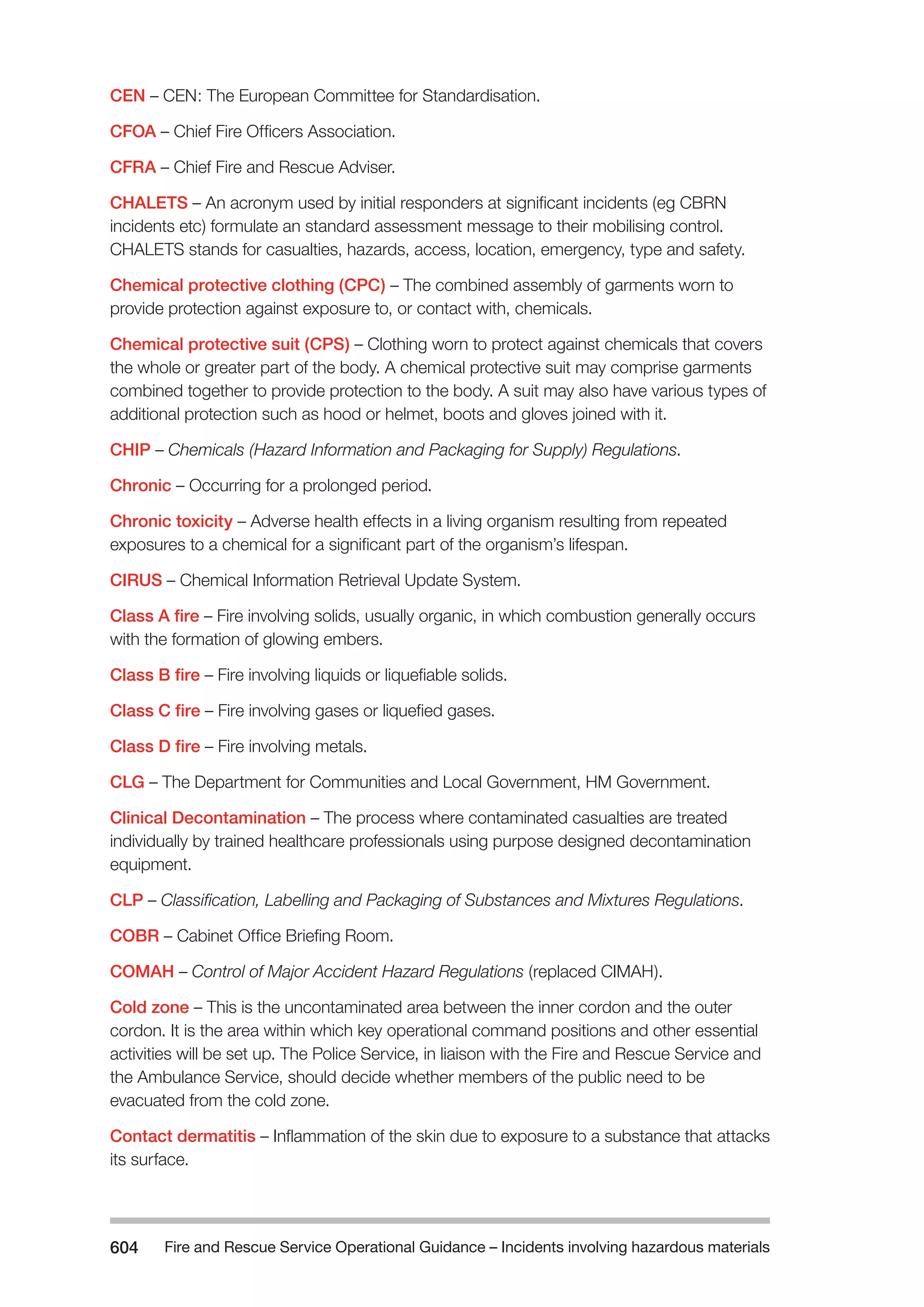

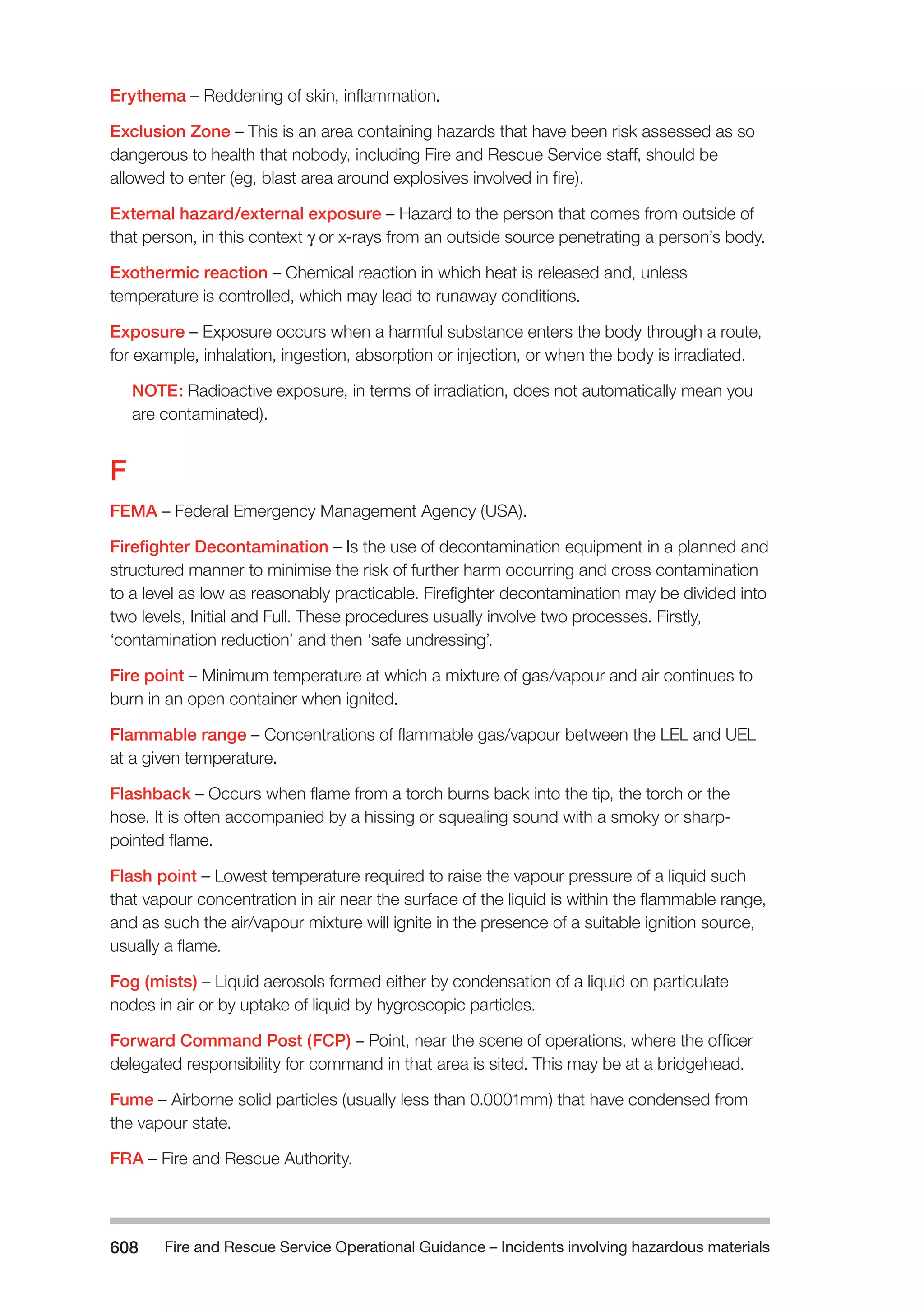

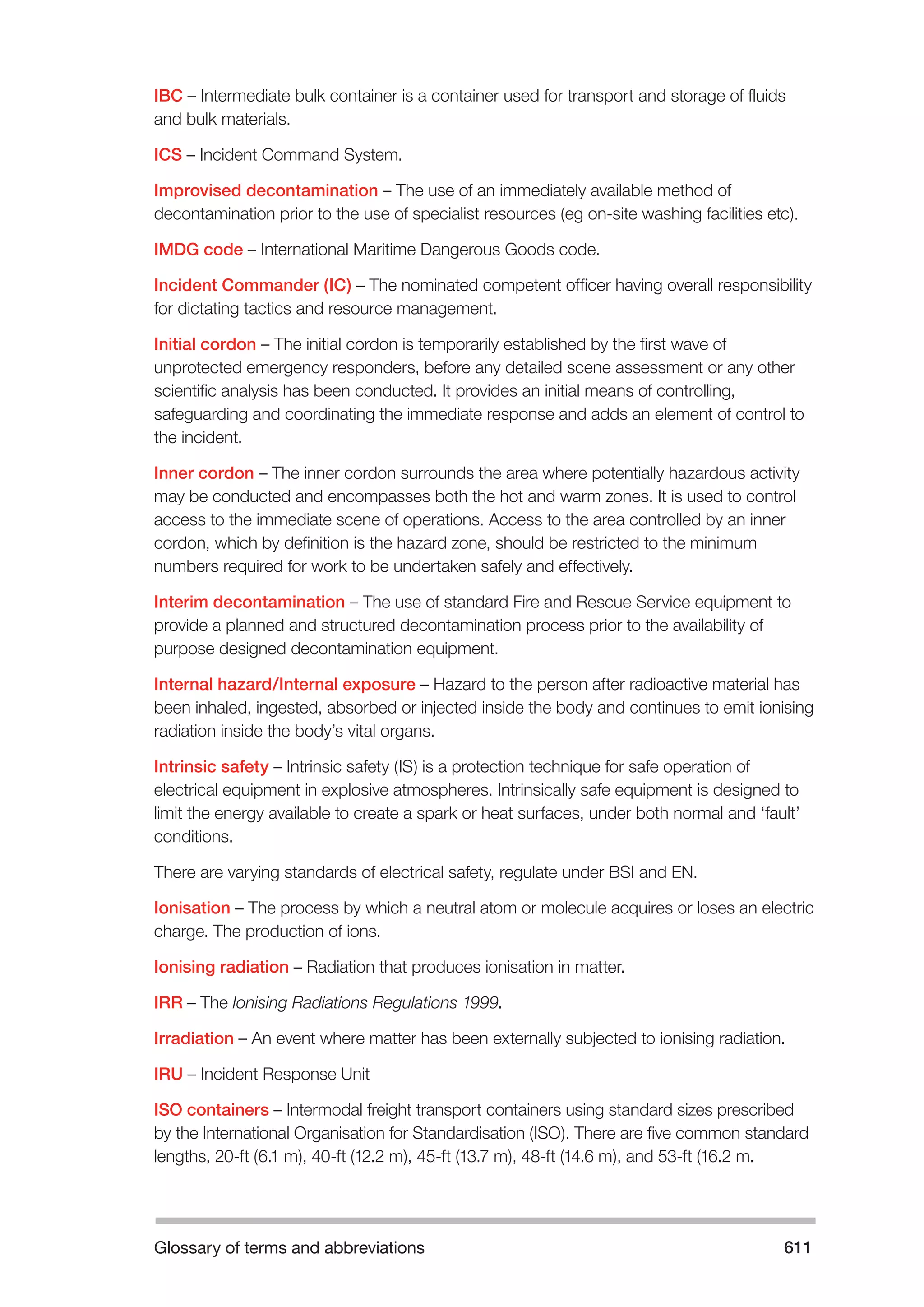

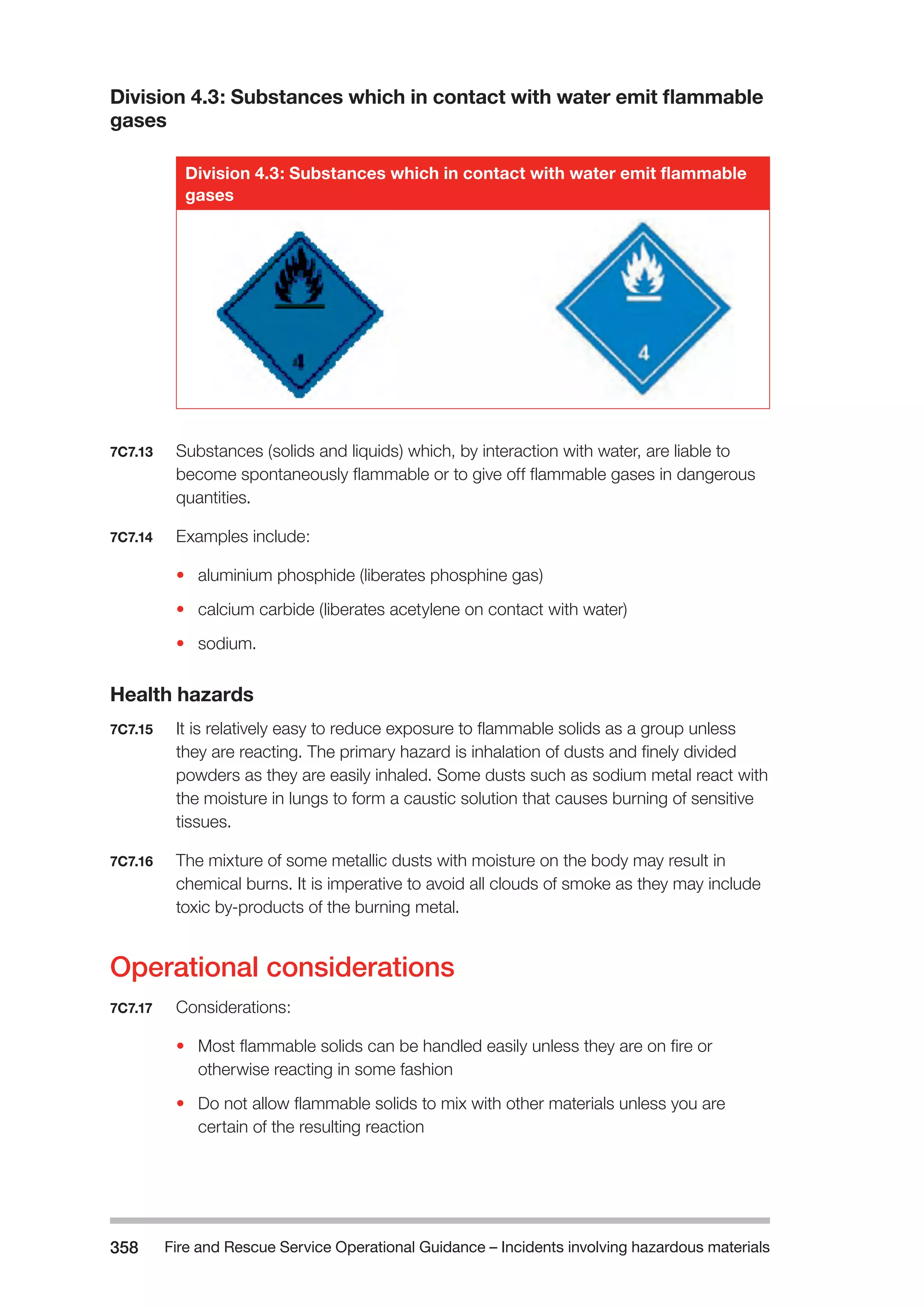

List of common salts and the acid from which they were formed

Acid Derived salt

Sulphuric Sulphate

Sulphurous Sulphite

Nitric Nitrate

Nitrous Nitrite

Hydrochloric Chloride

Hydrofluoric Fluoride

Acetic a.k.a. Ethanoic Acetate, ethanoate

Oxalic Oxalate

Carbonic Carbonate

7C11.21 The other half of the name of the salt comes from the base with which it has

reacted, eg, sodium hydroxide will produce sodium salts and ammonium

hydroxide will produce ammonium salts.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7rbqzs77riklyjybirhl-signature-8ae49c26427c42a89a6d4352195b02a6095bd9fa5df6c0500639463b6450e515-poli-140828111115-phpapp02/75/The-Fire-and-Rescue-Service-Books-is-a-guidance-for-organize-a-safe-system-of-work-on-the-incident-ground-with-hazardous-materials-423-2048.jpg)

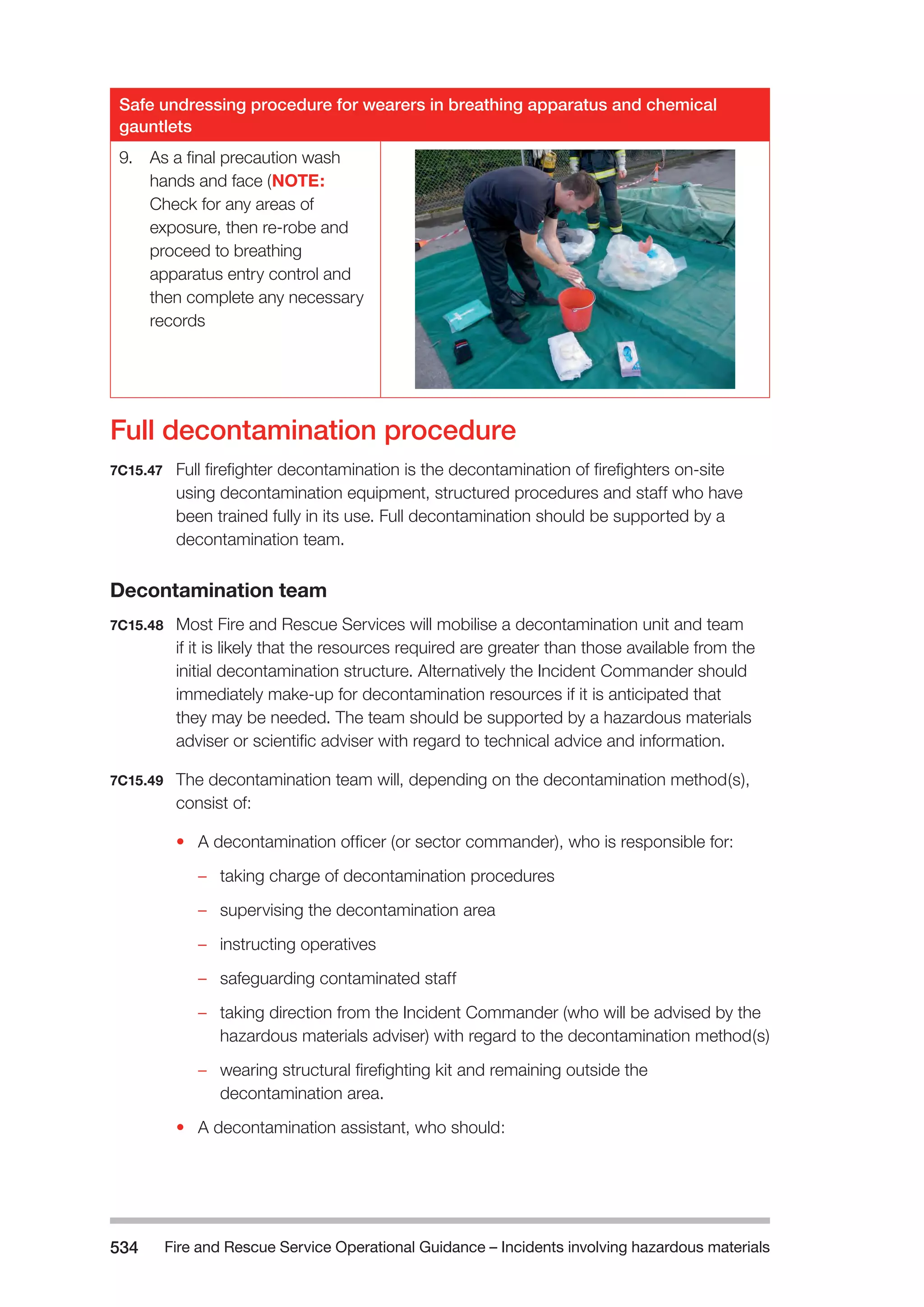

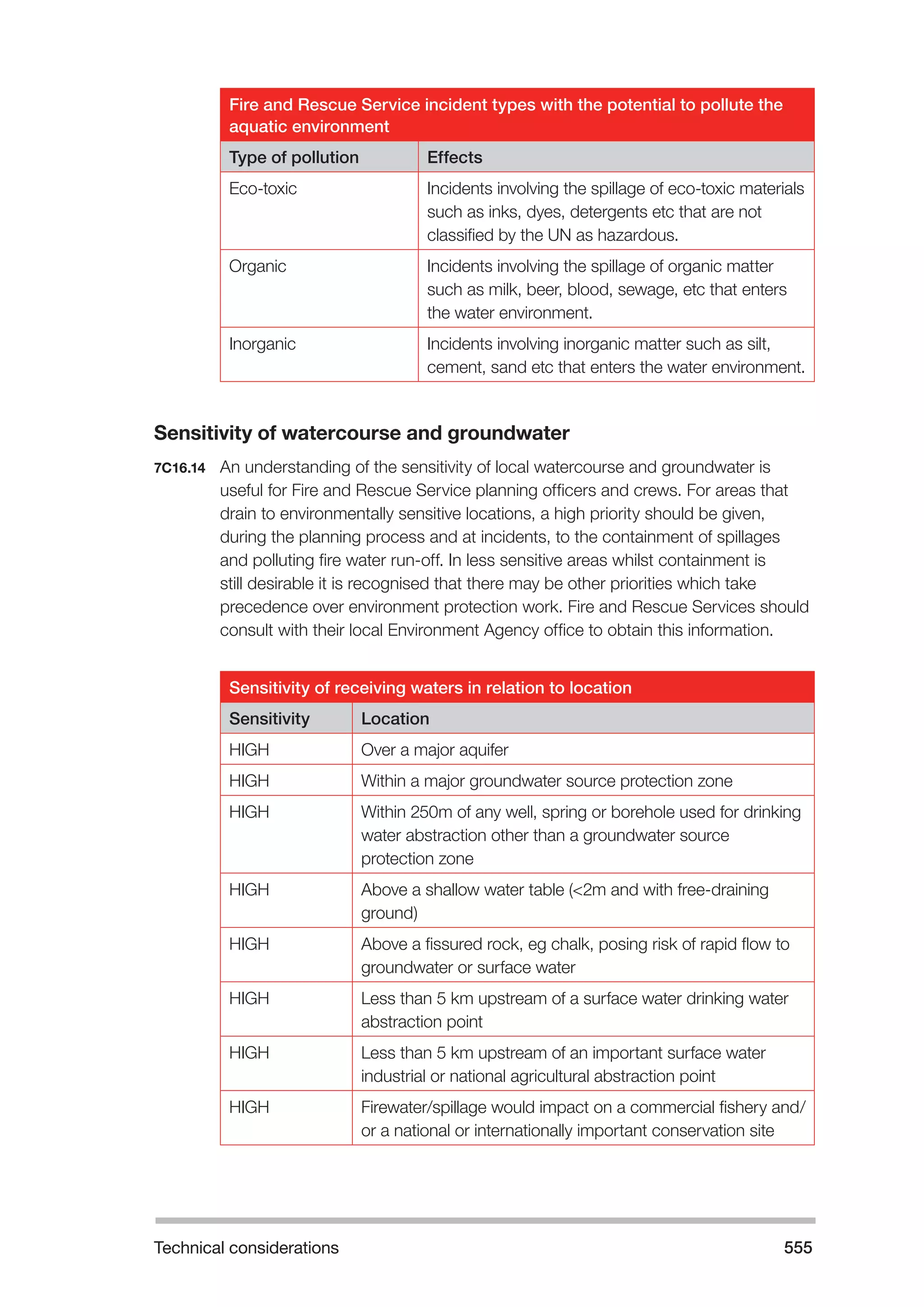

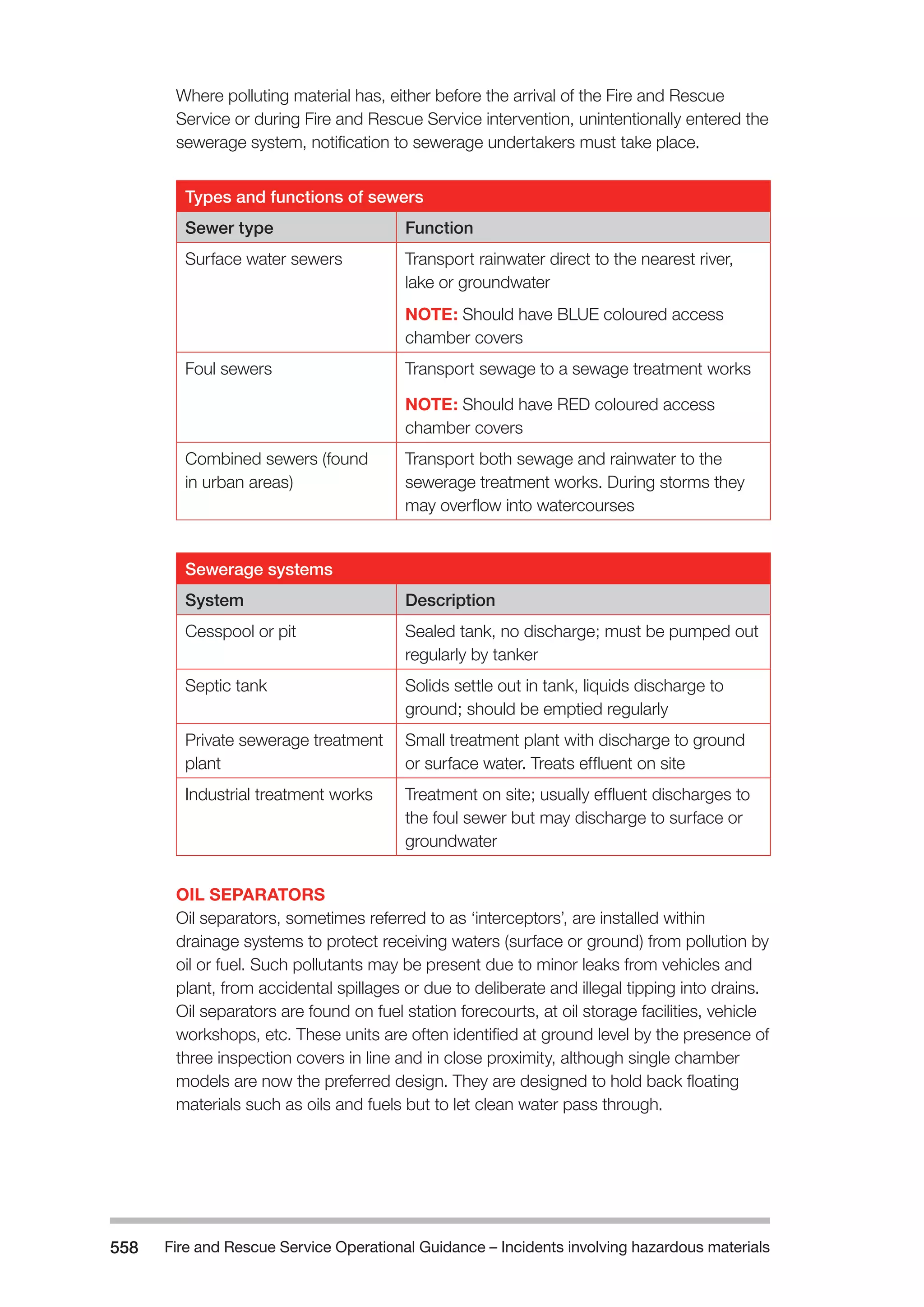

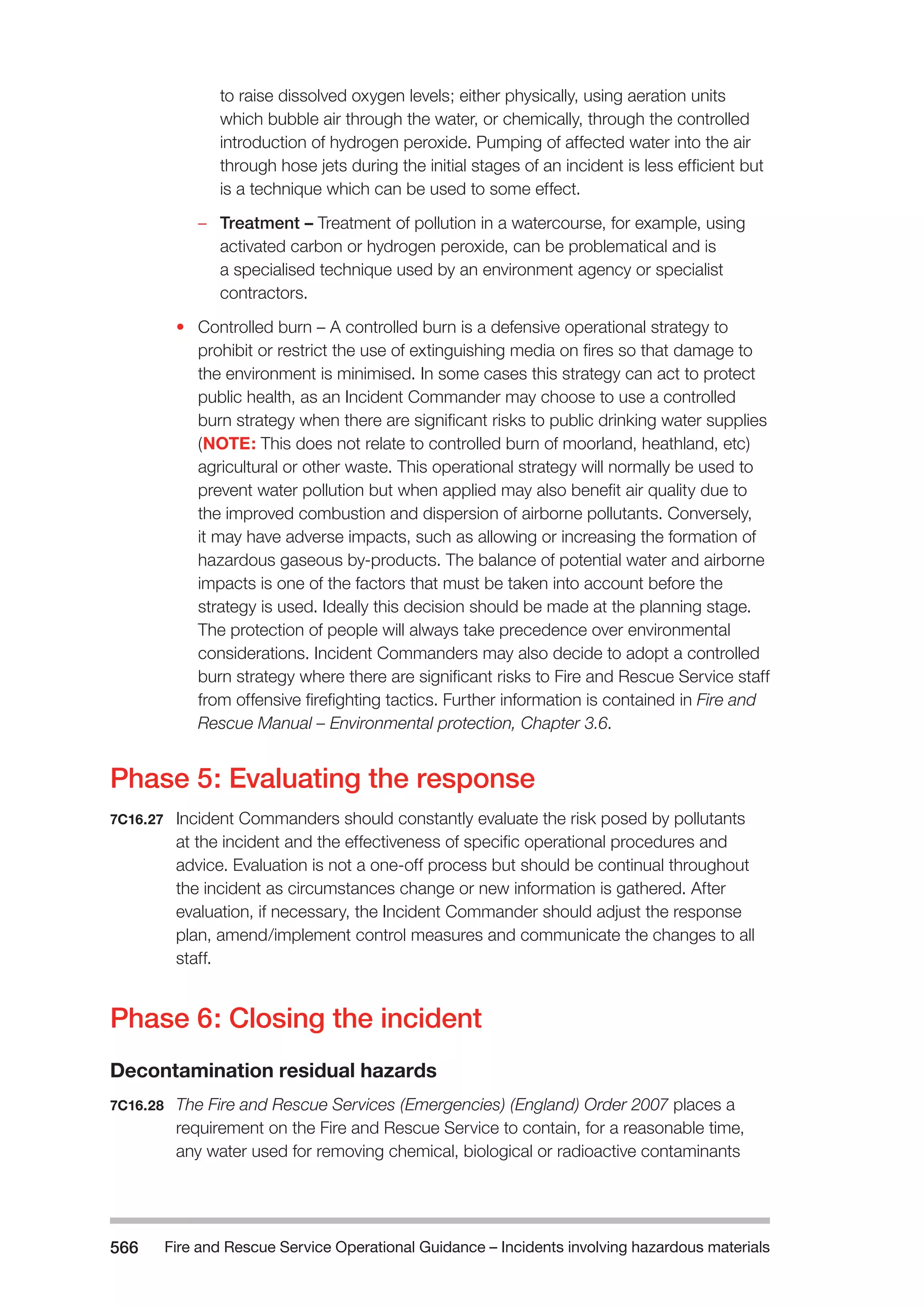

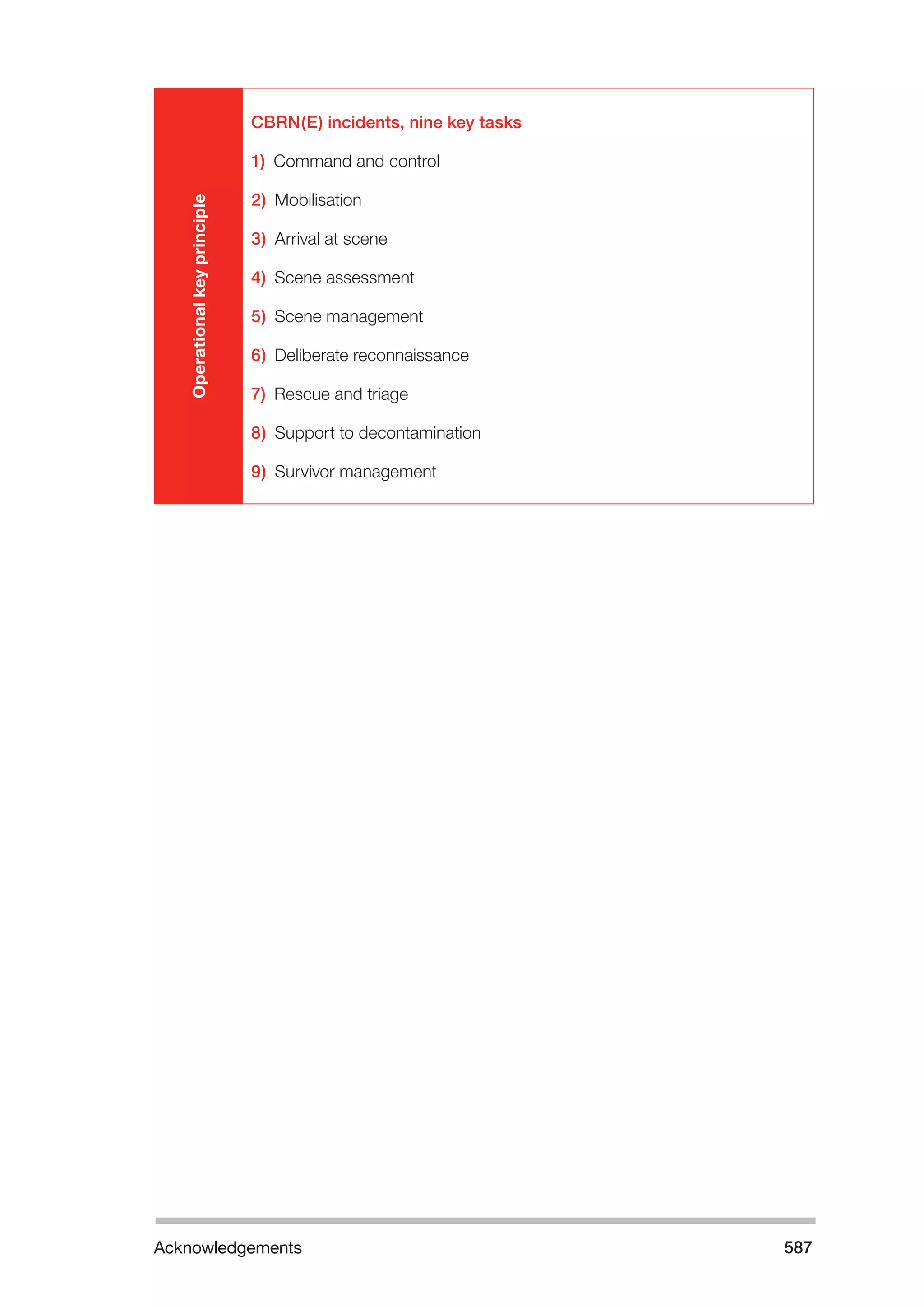

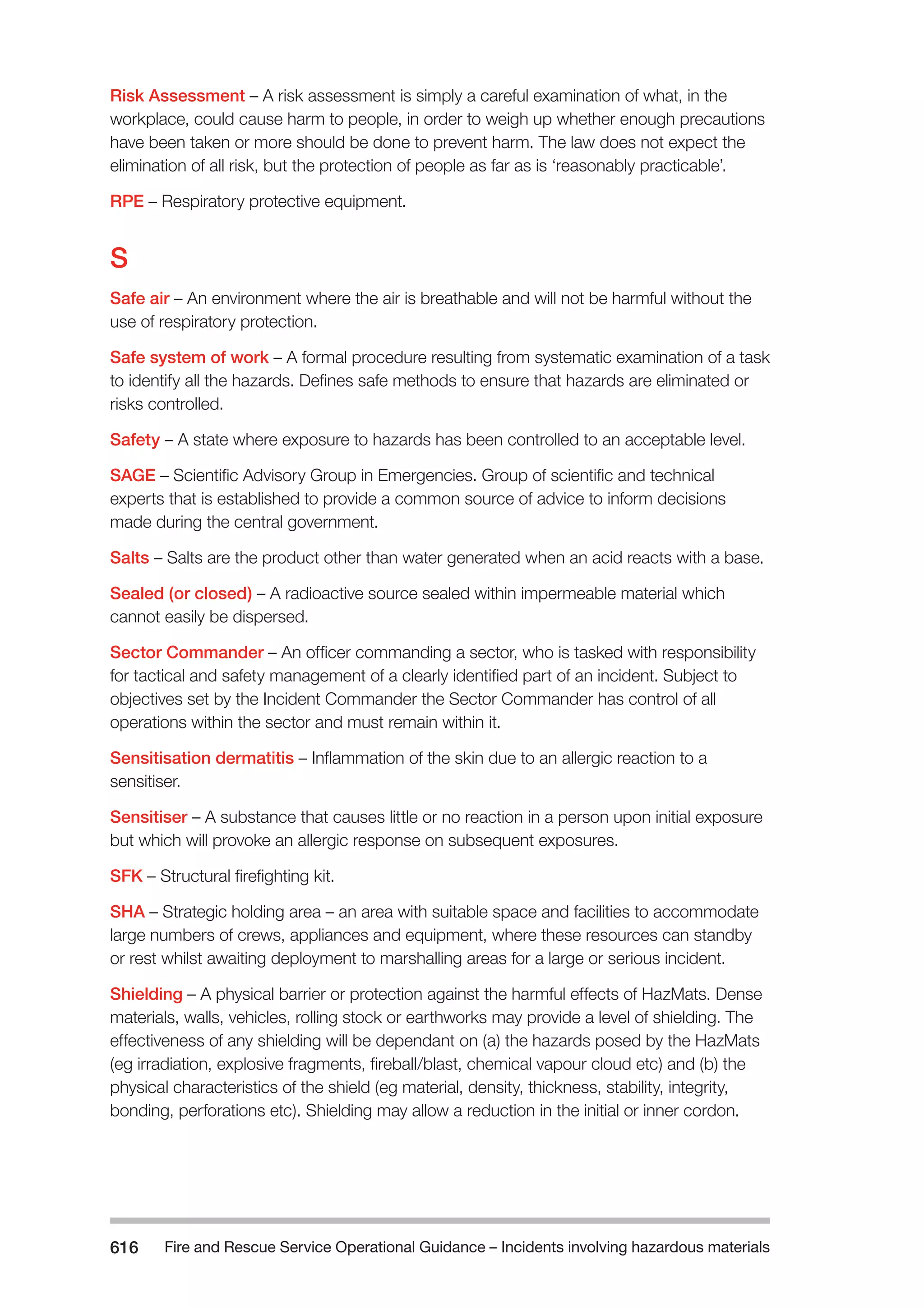

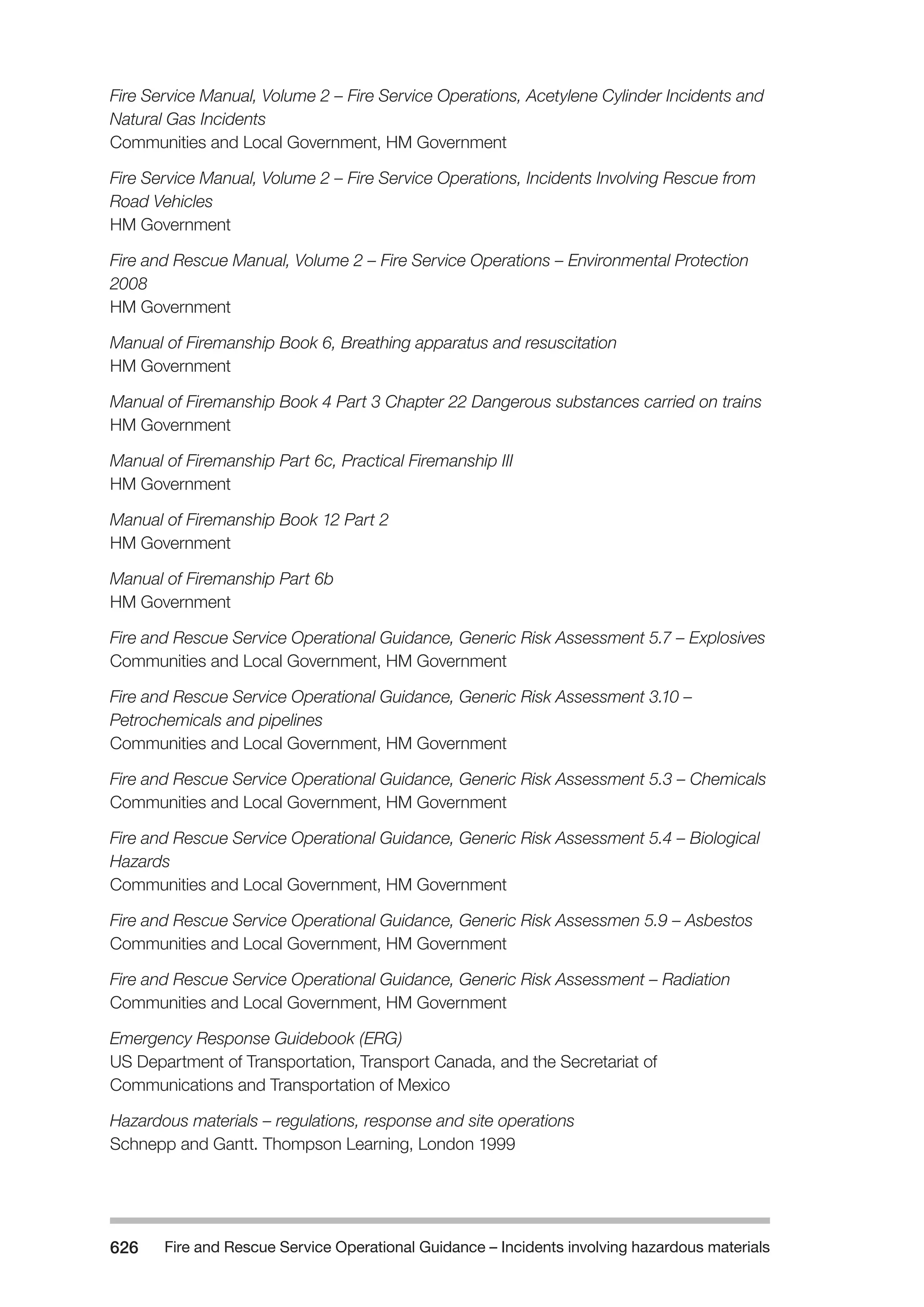

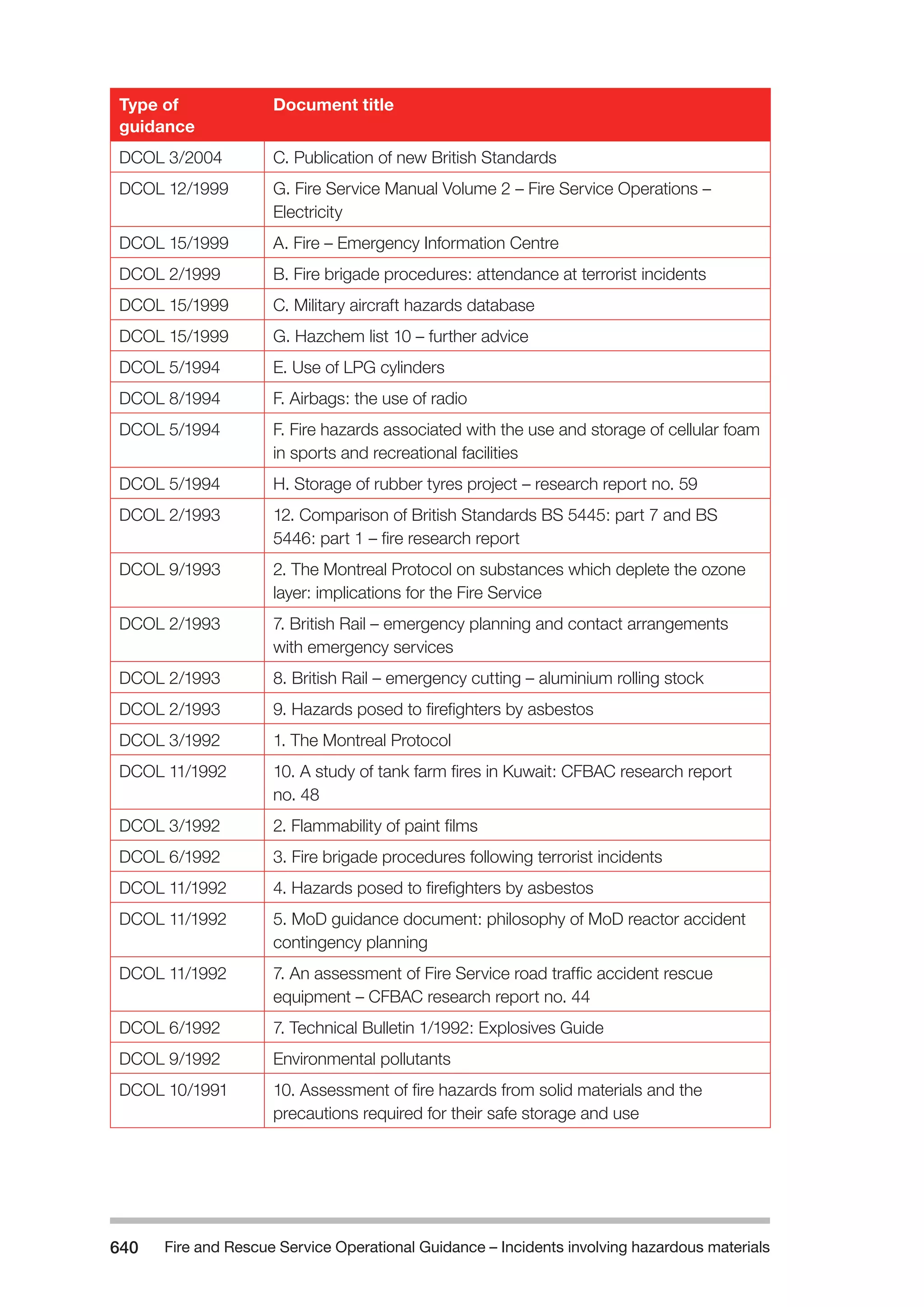

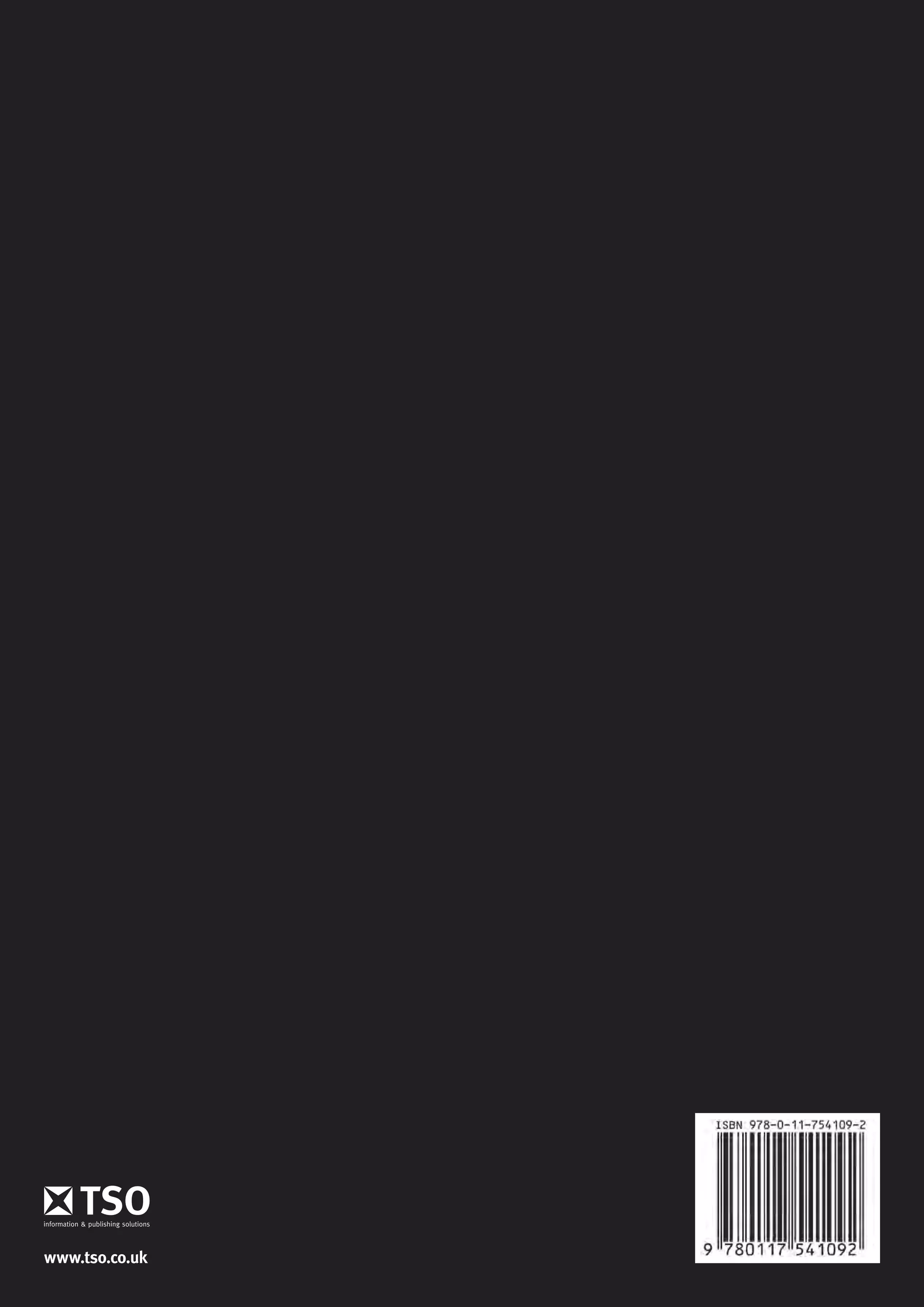

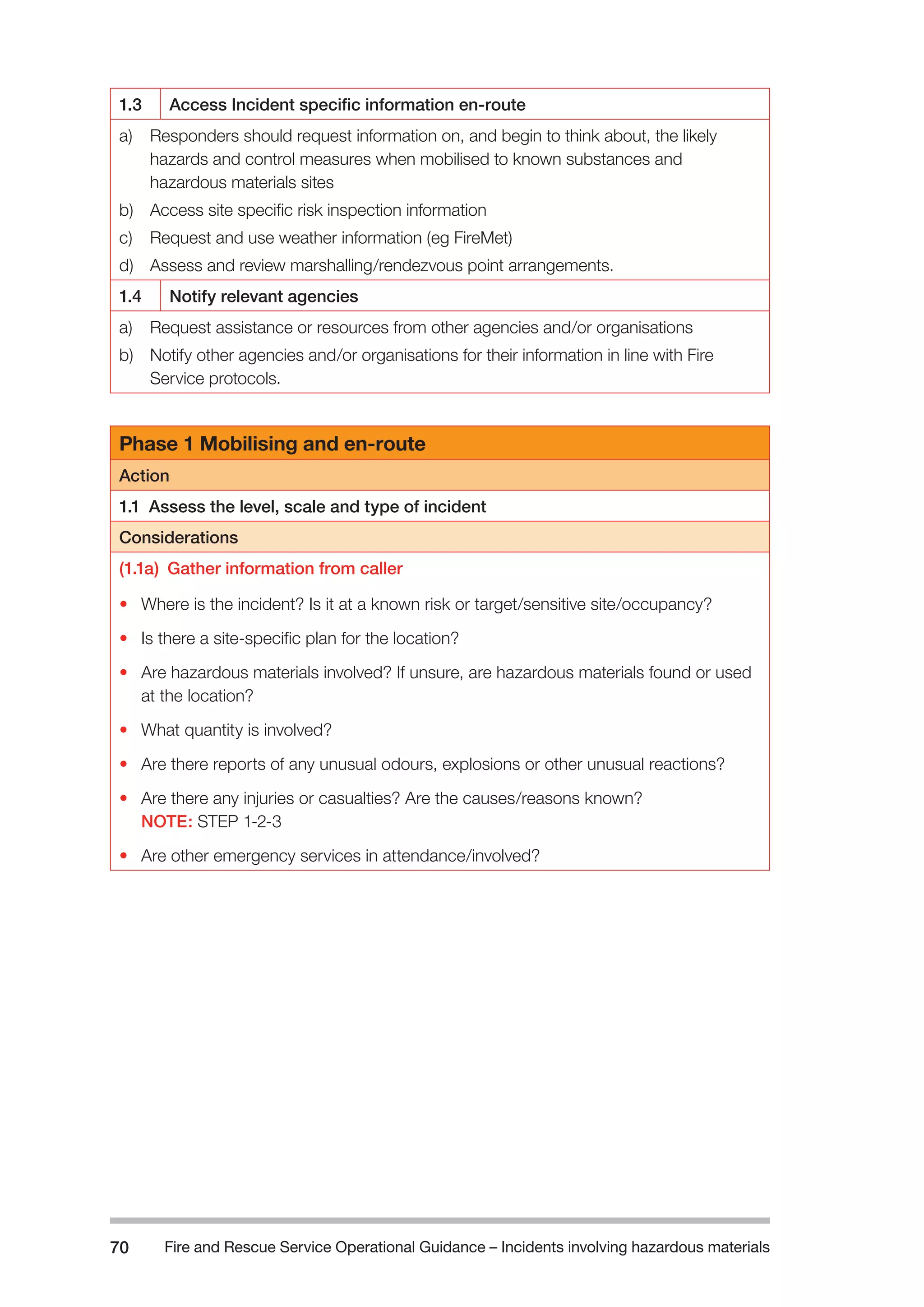

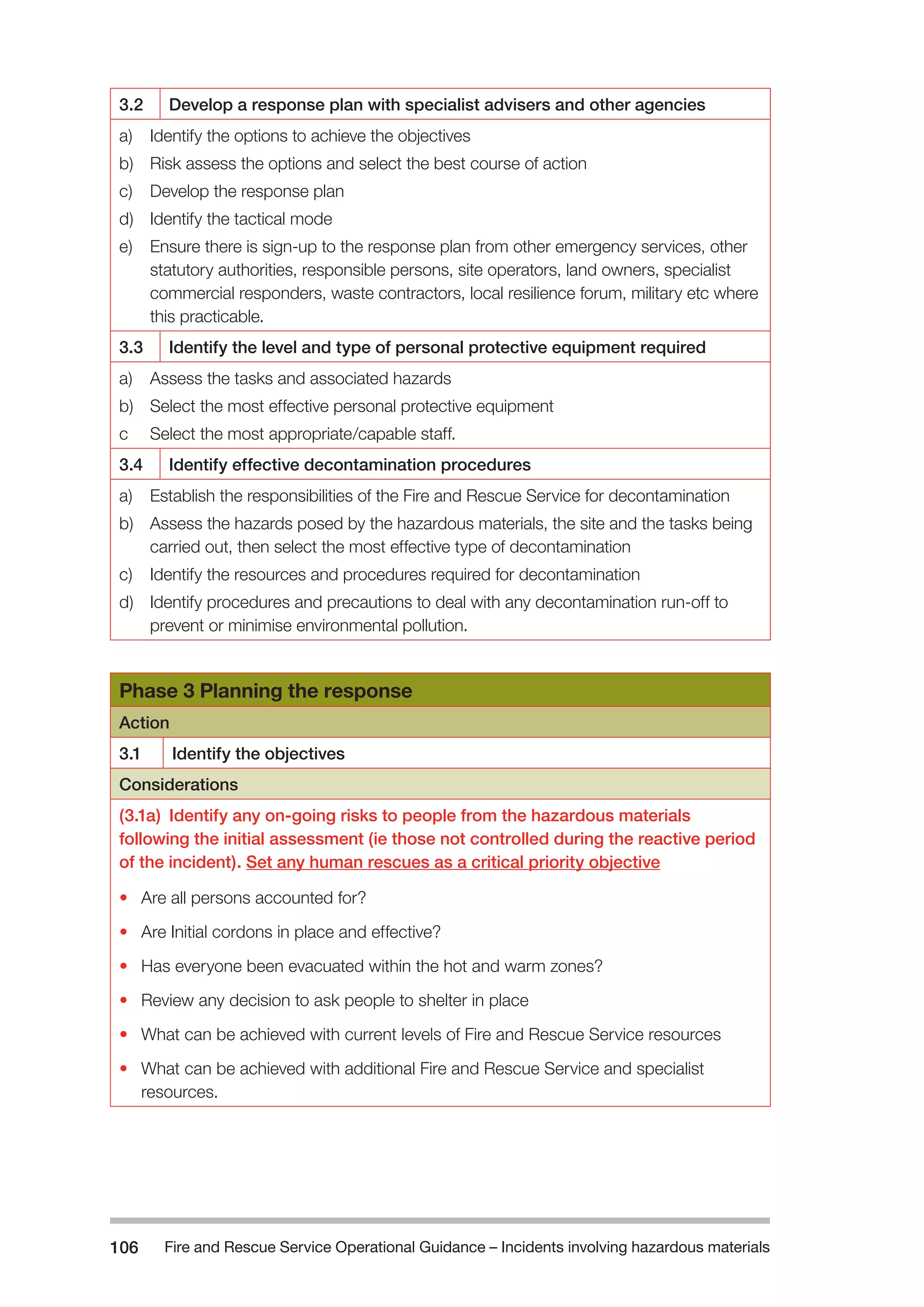

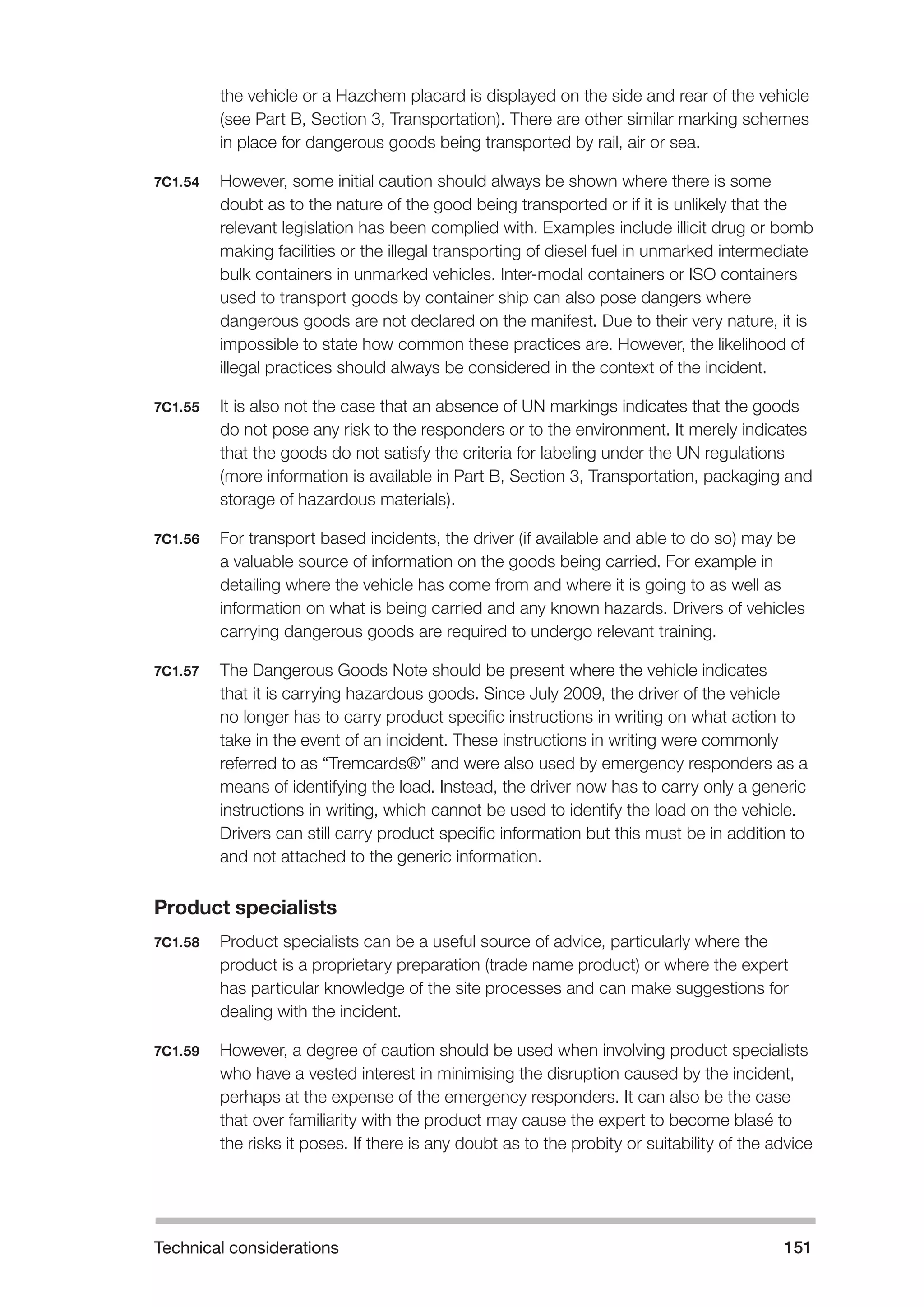

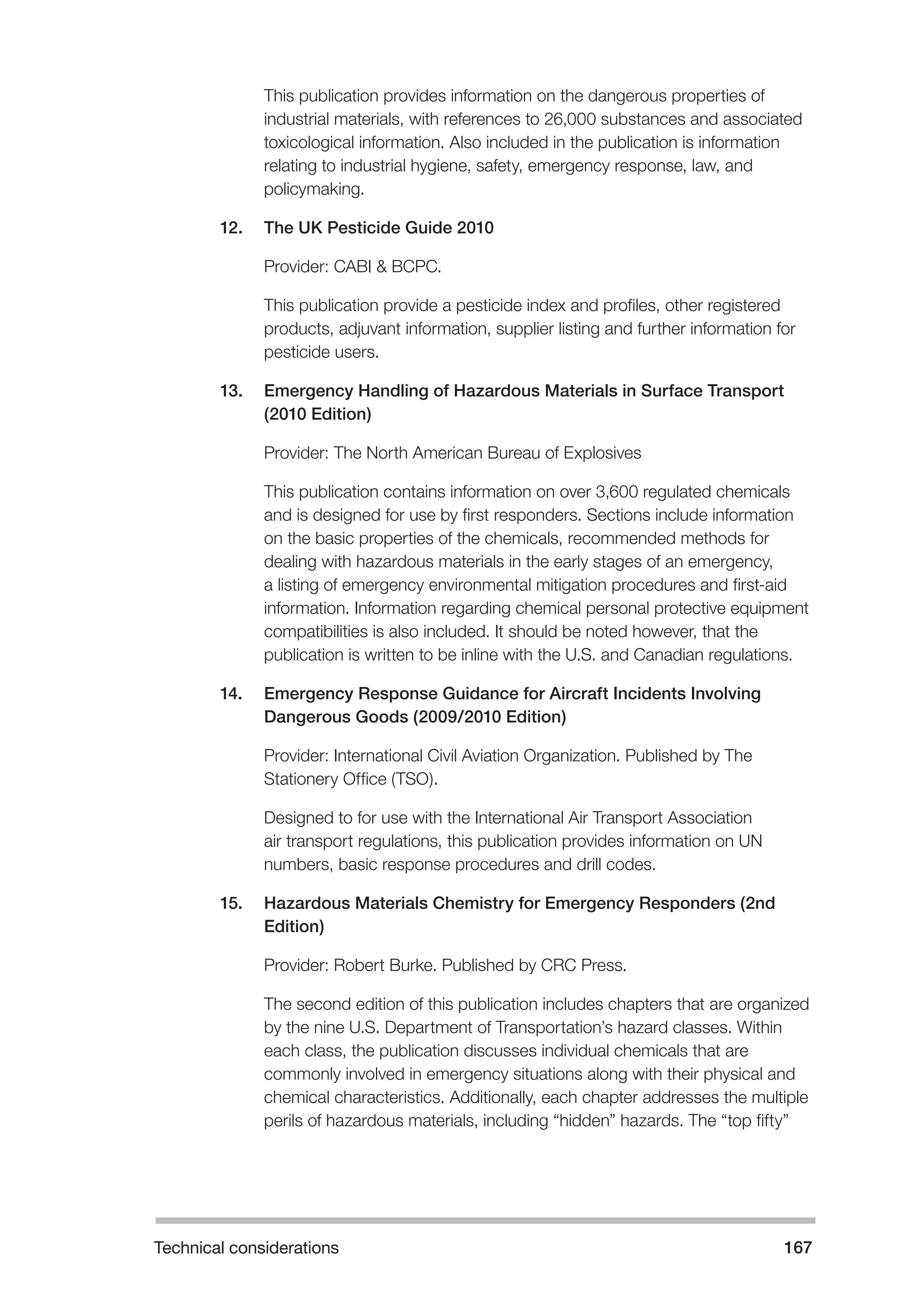

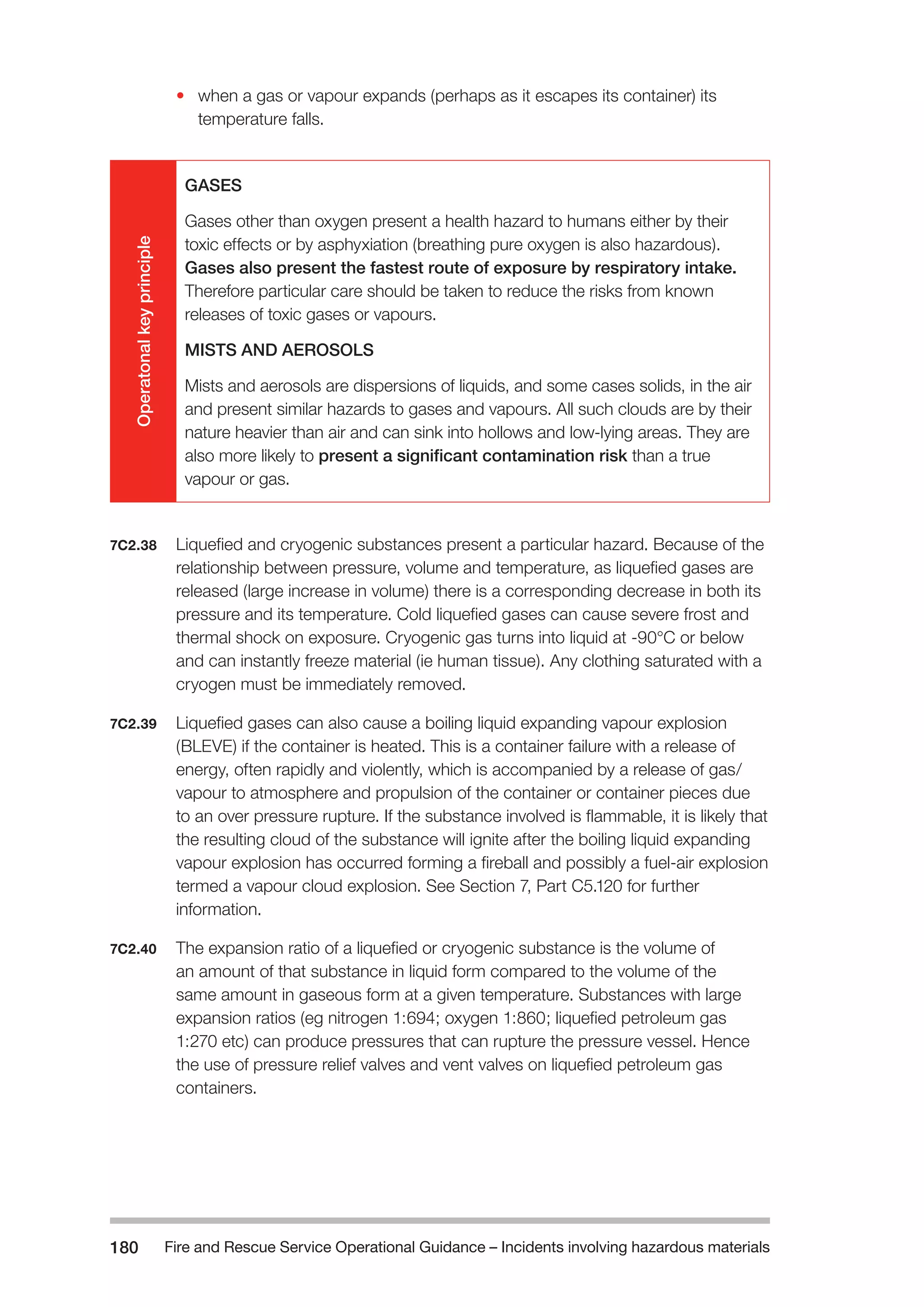

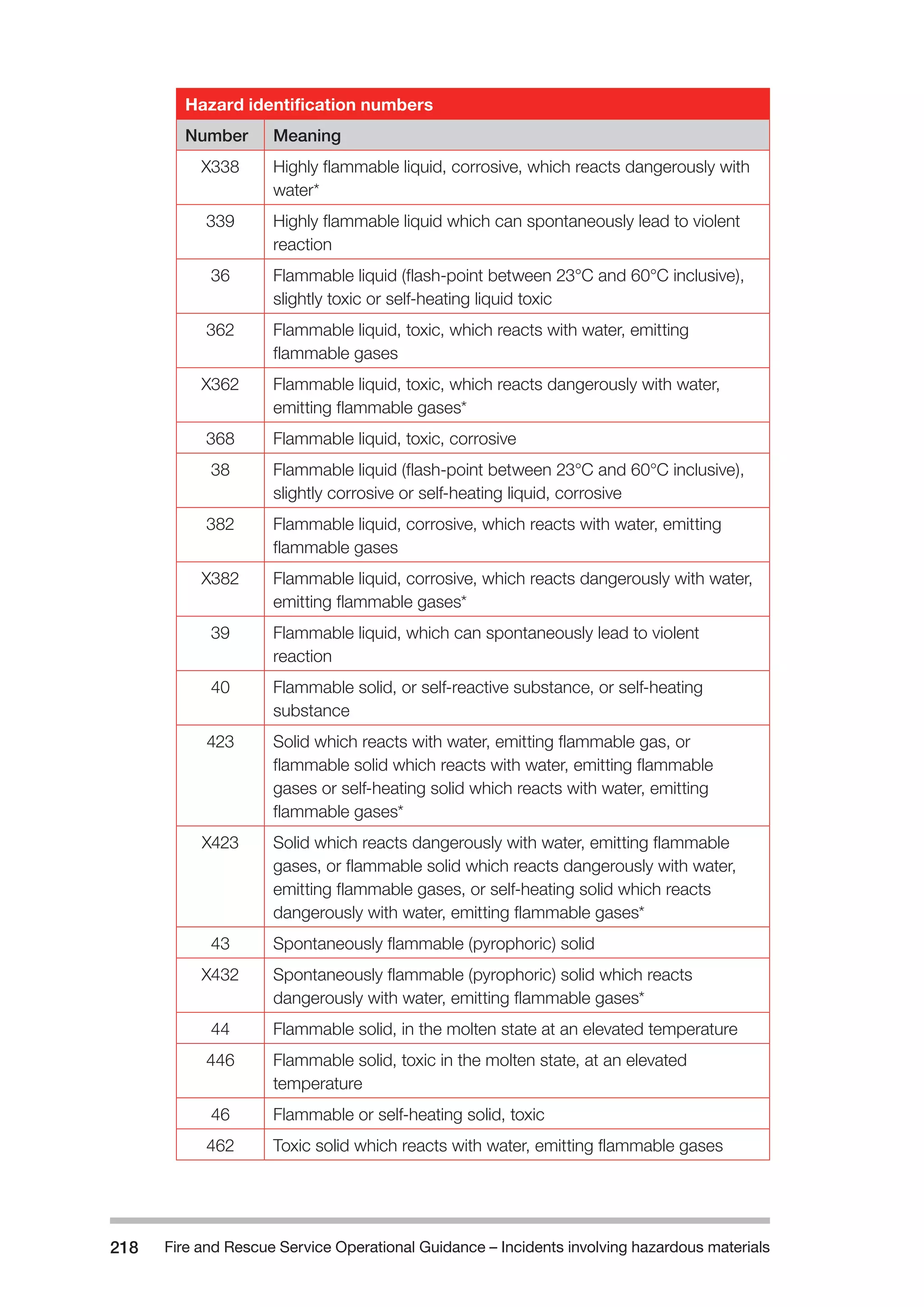

![Fire and Rescue Service Operational Guidance – Incidents 494 involving hazardous materials

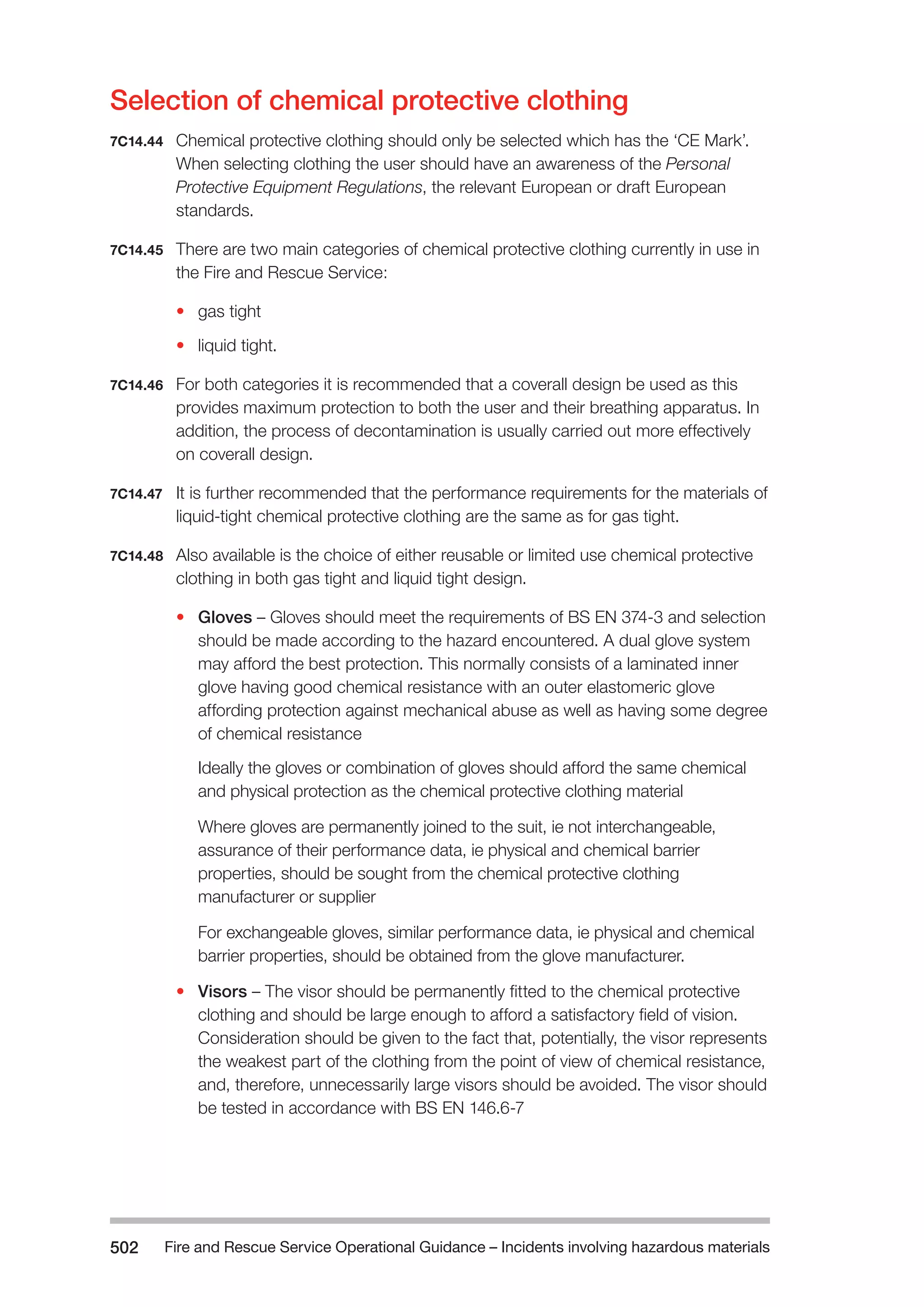

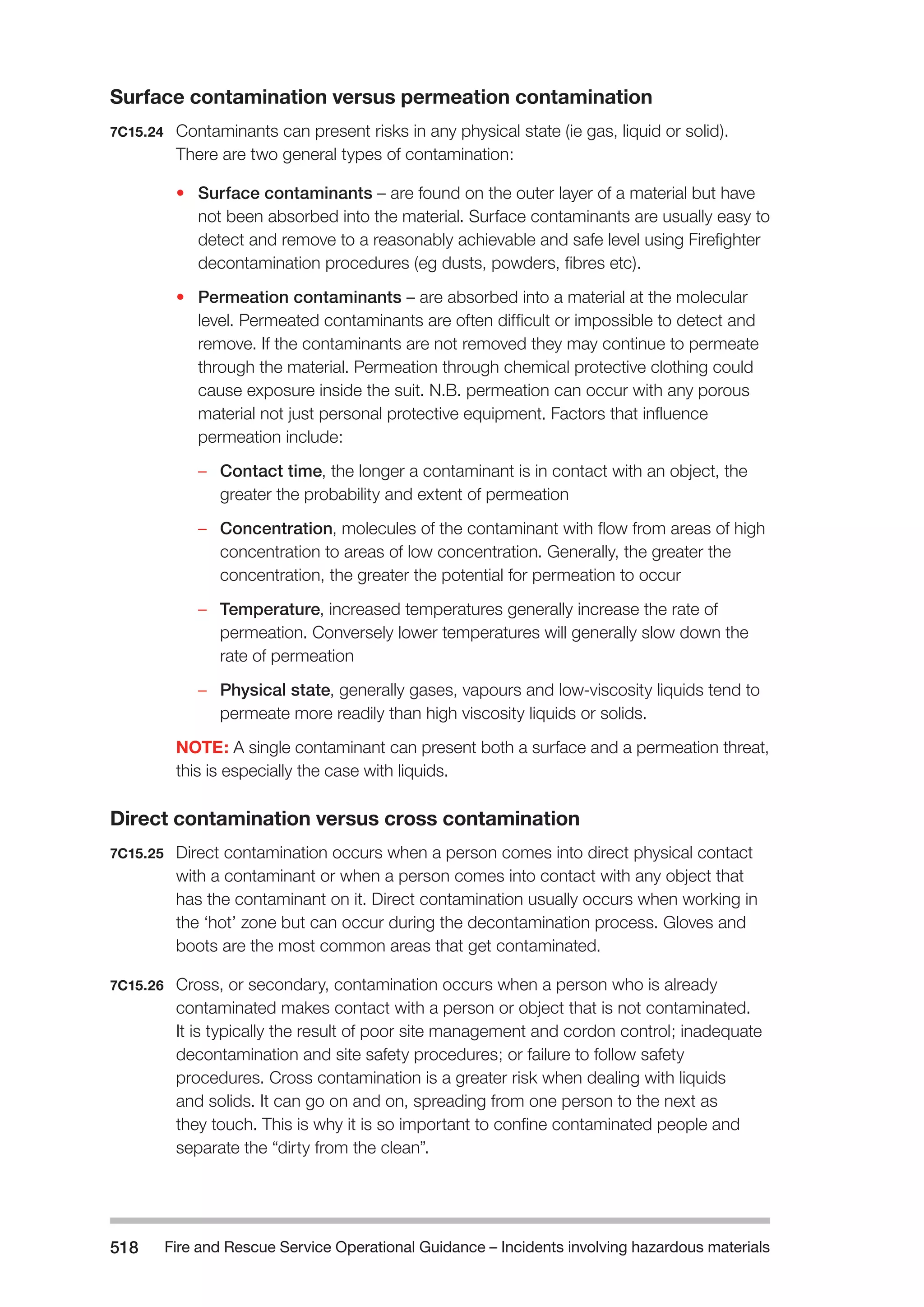

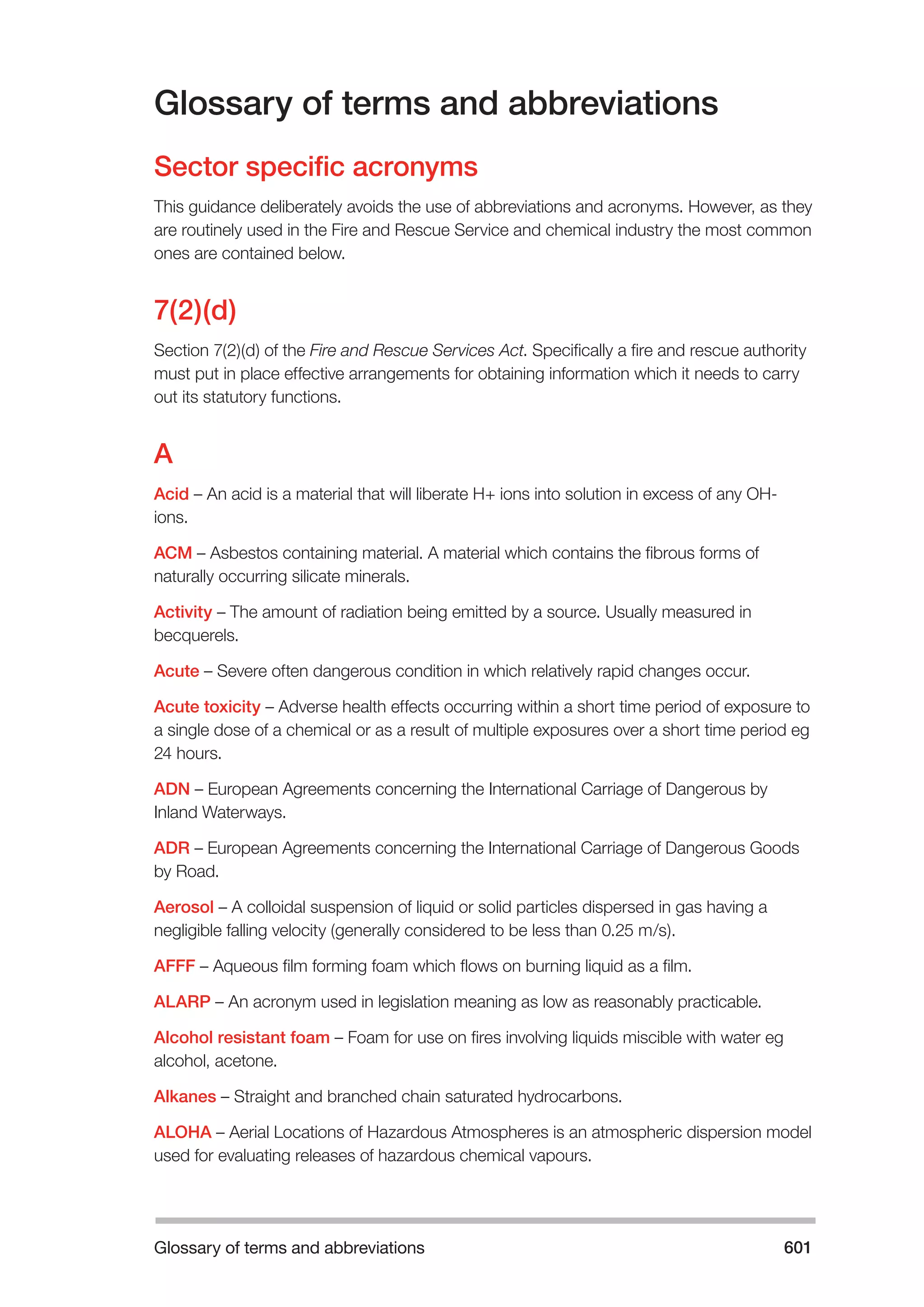

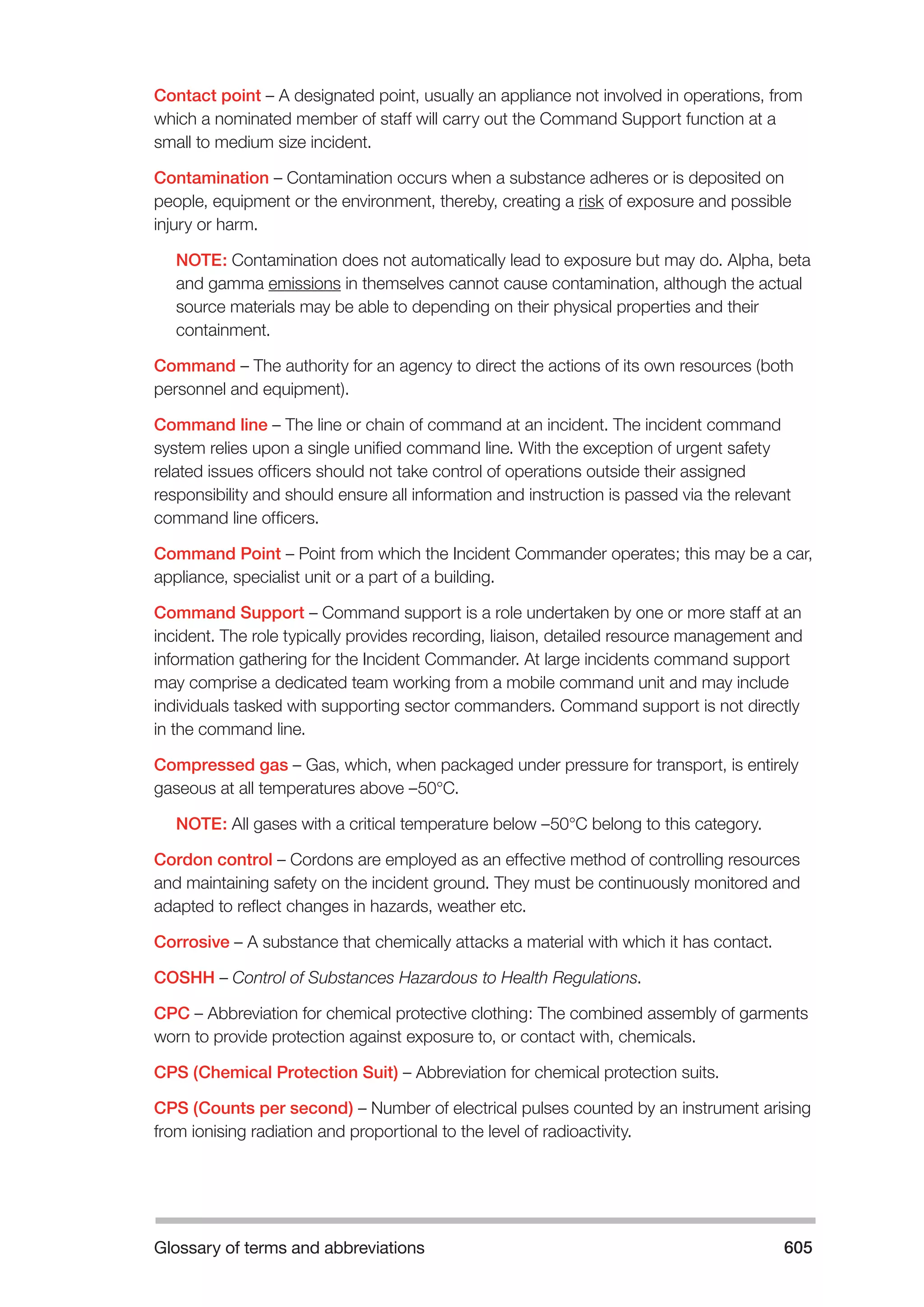

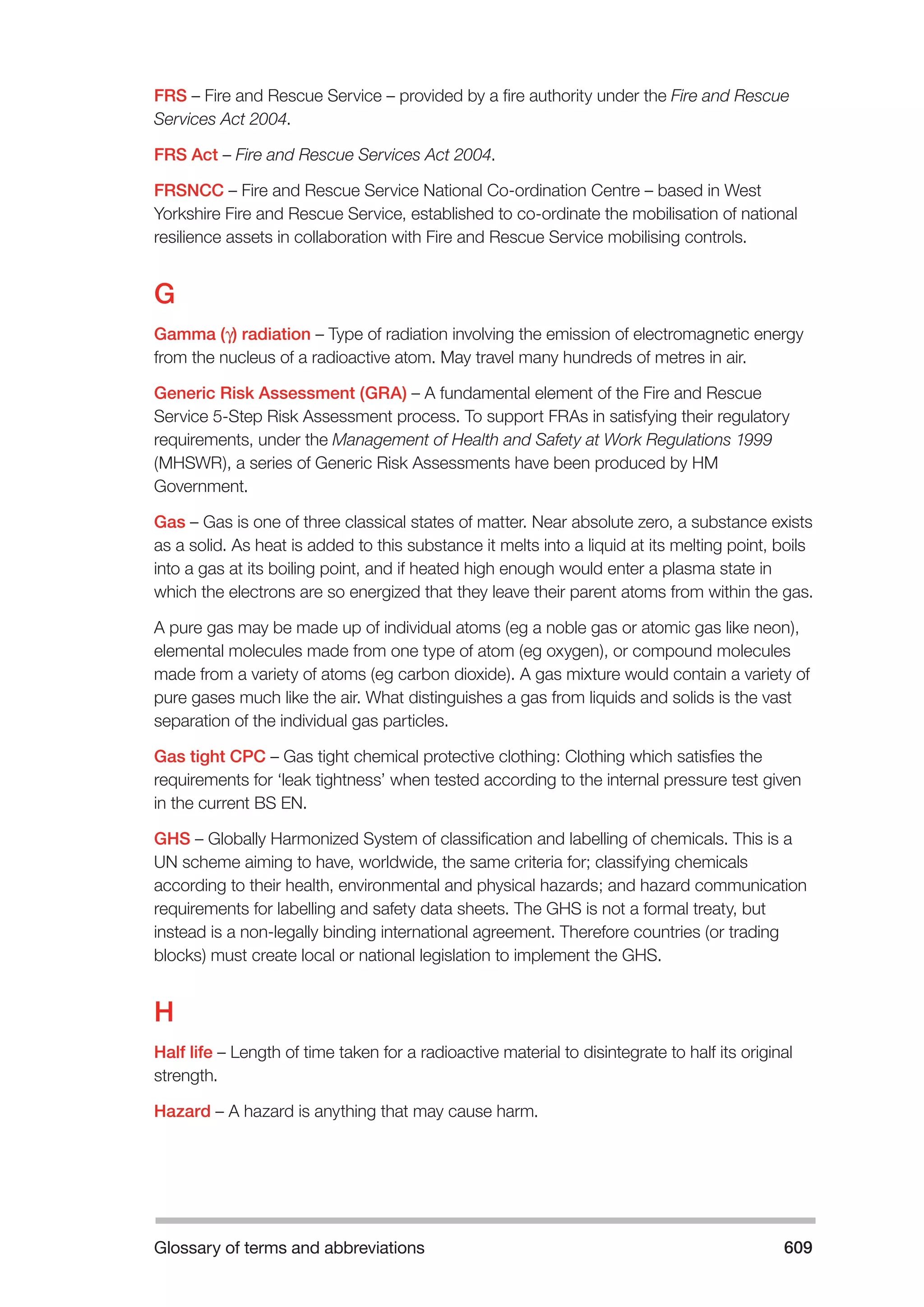

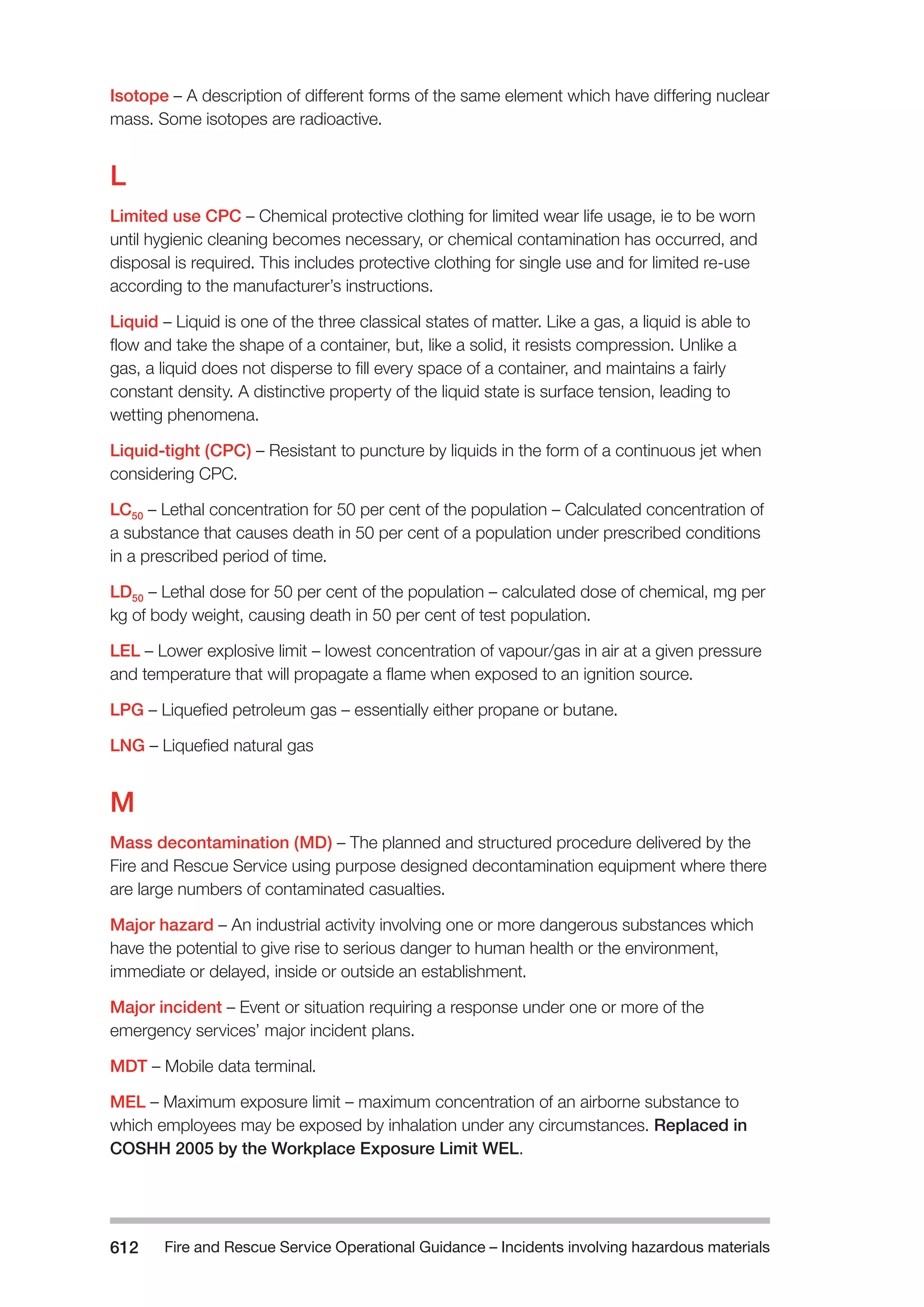

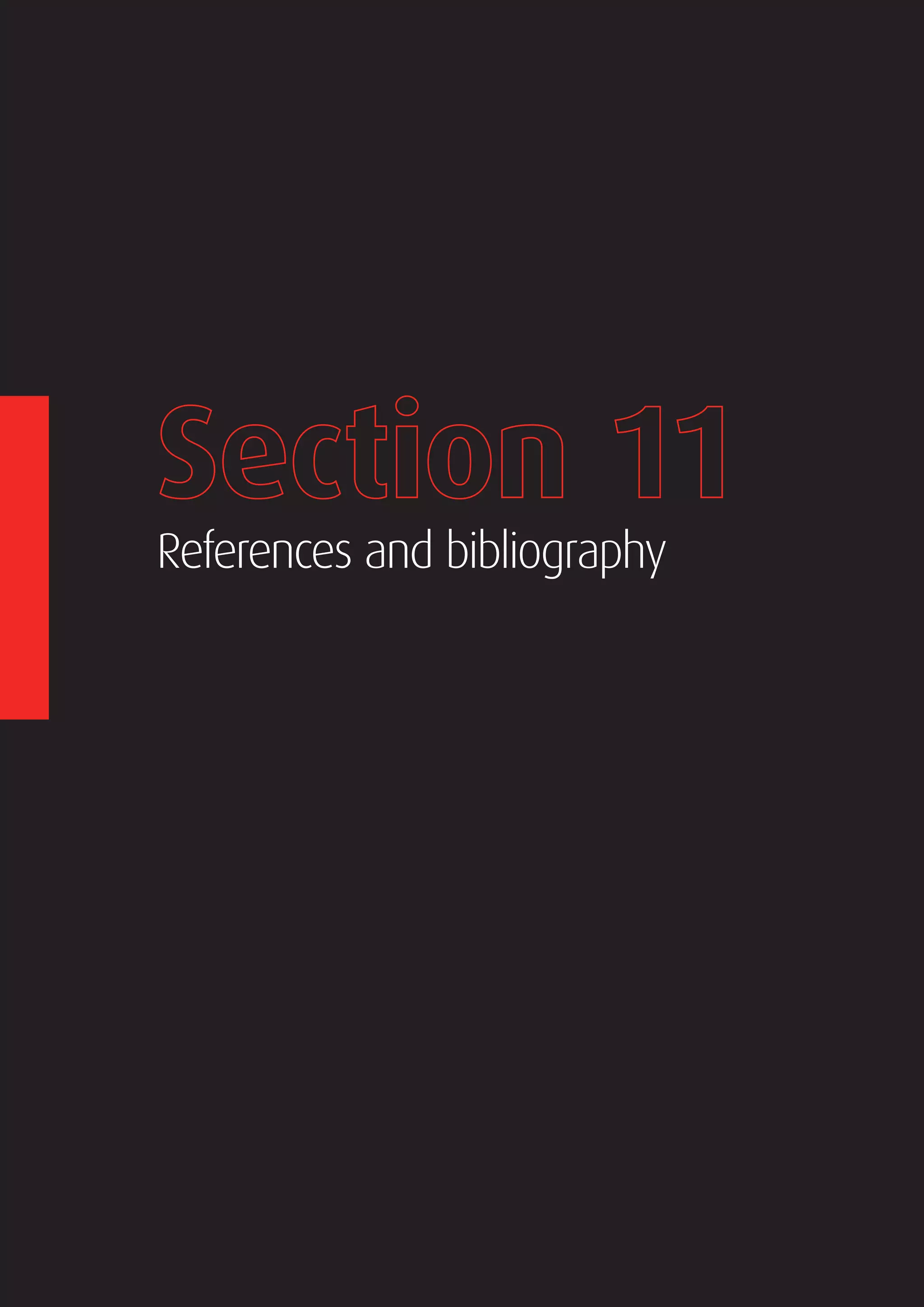

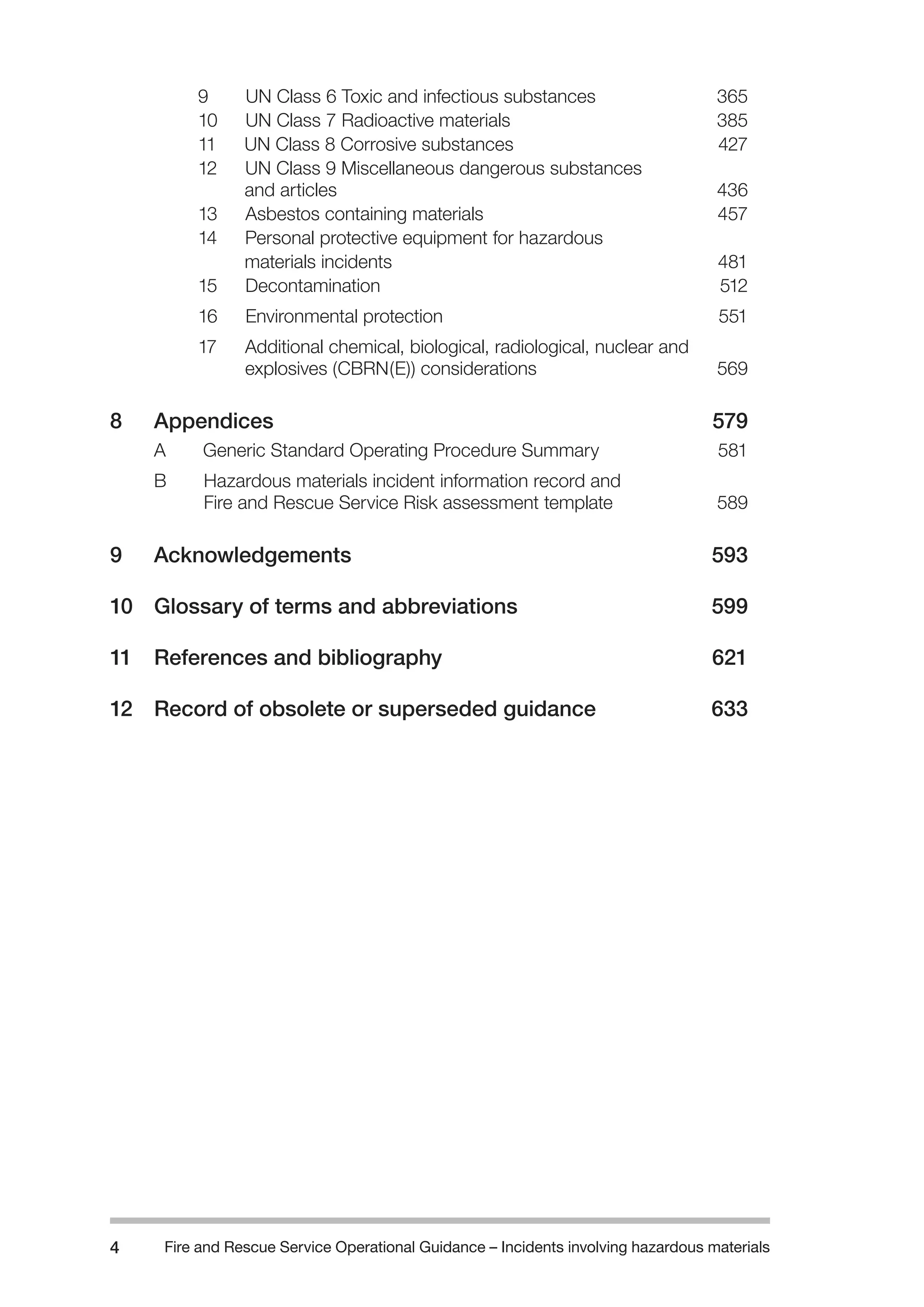

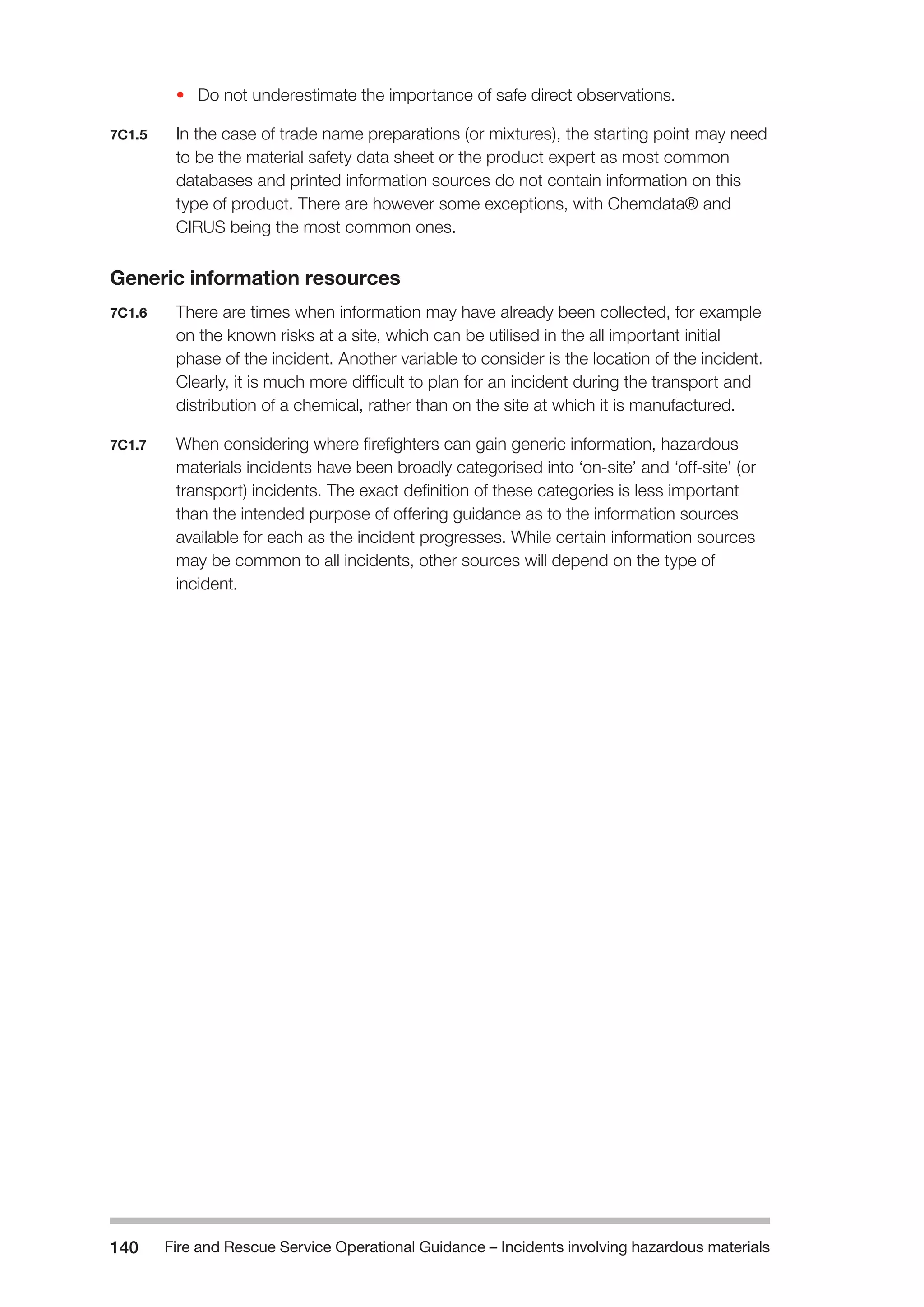

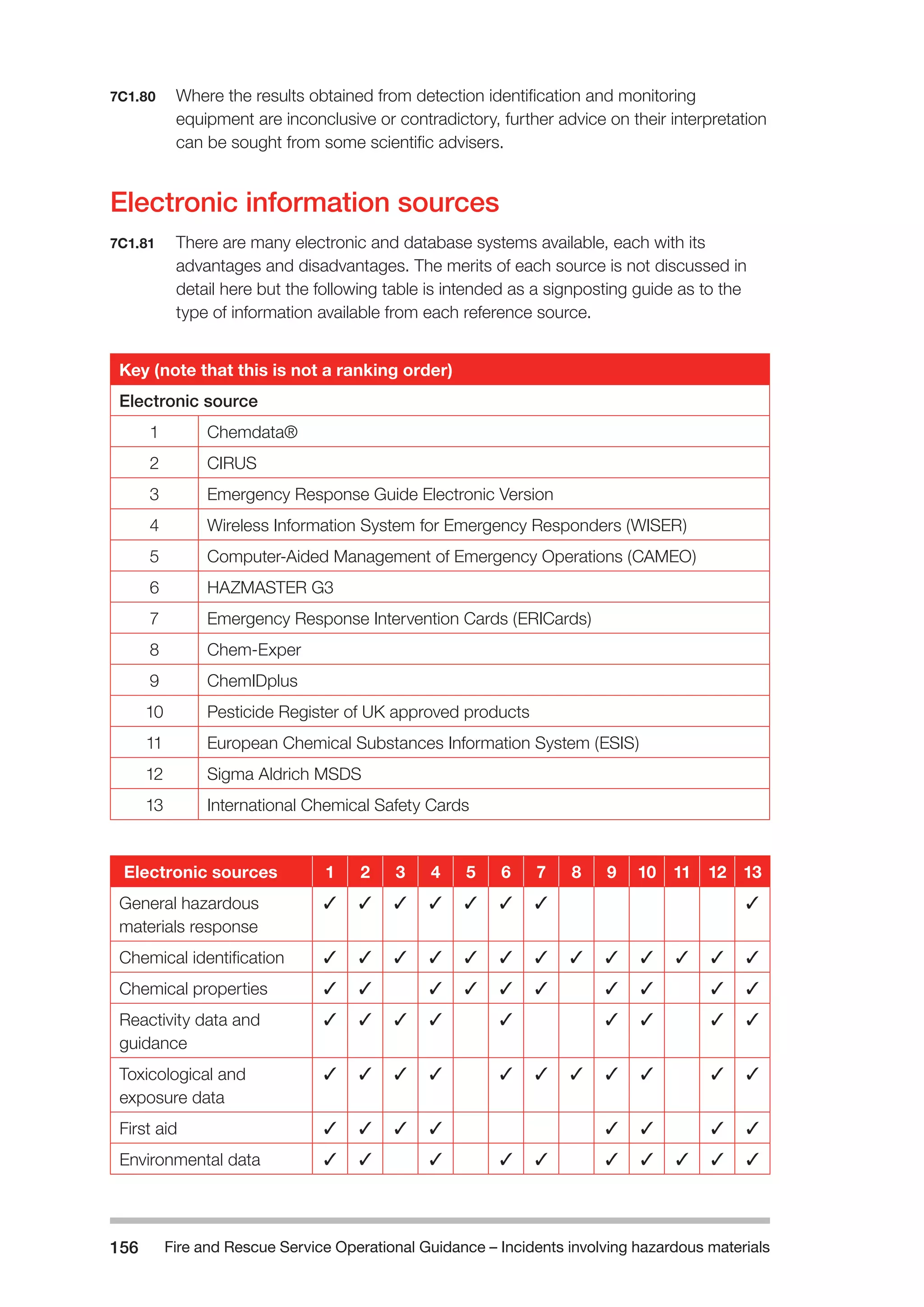

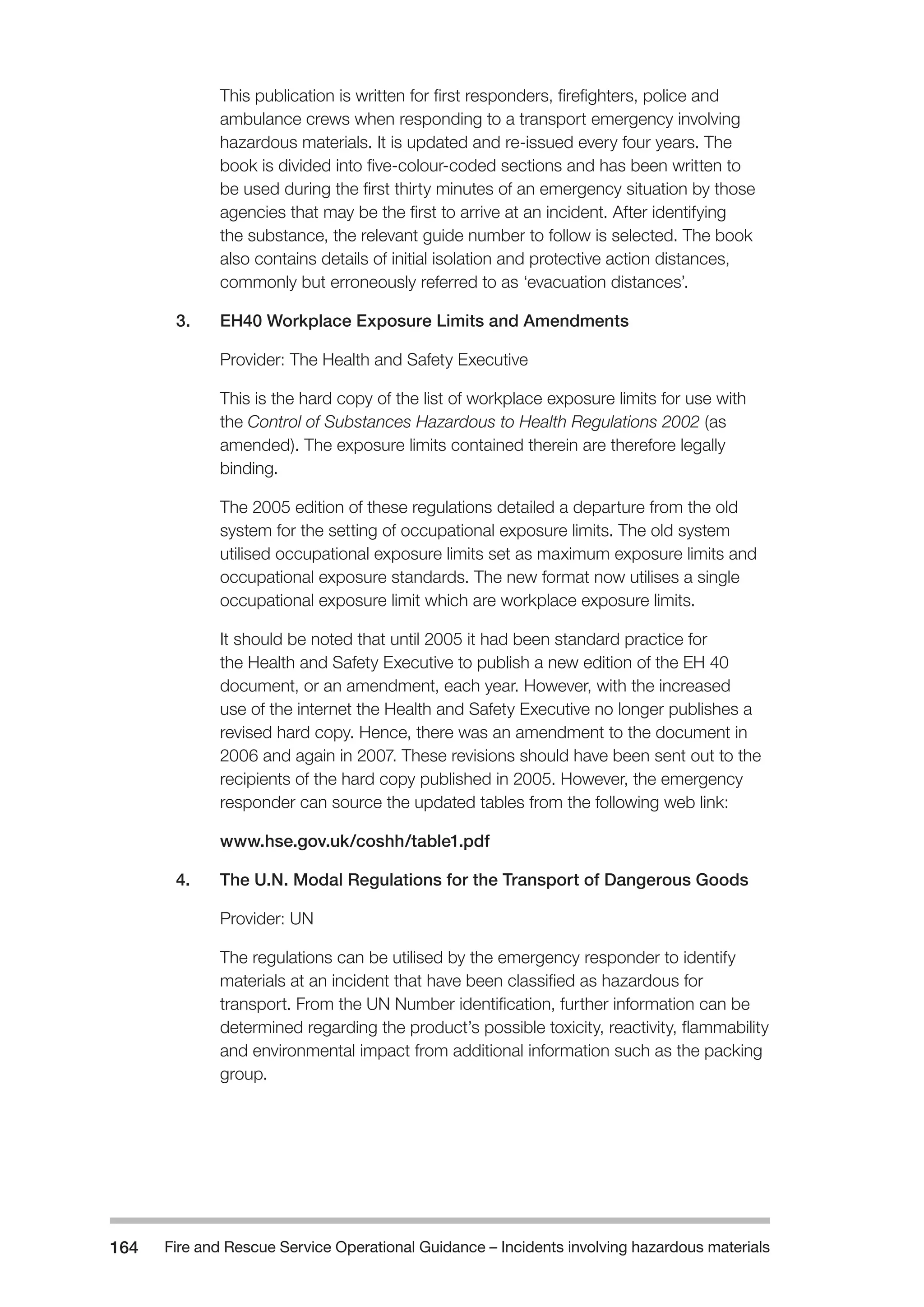

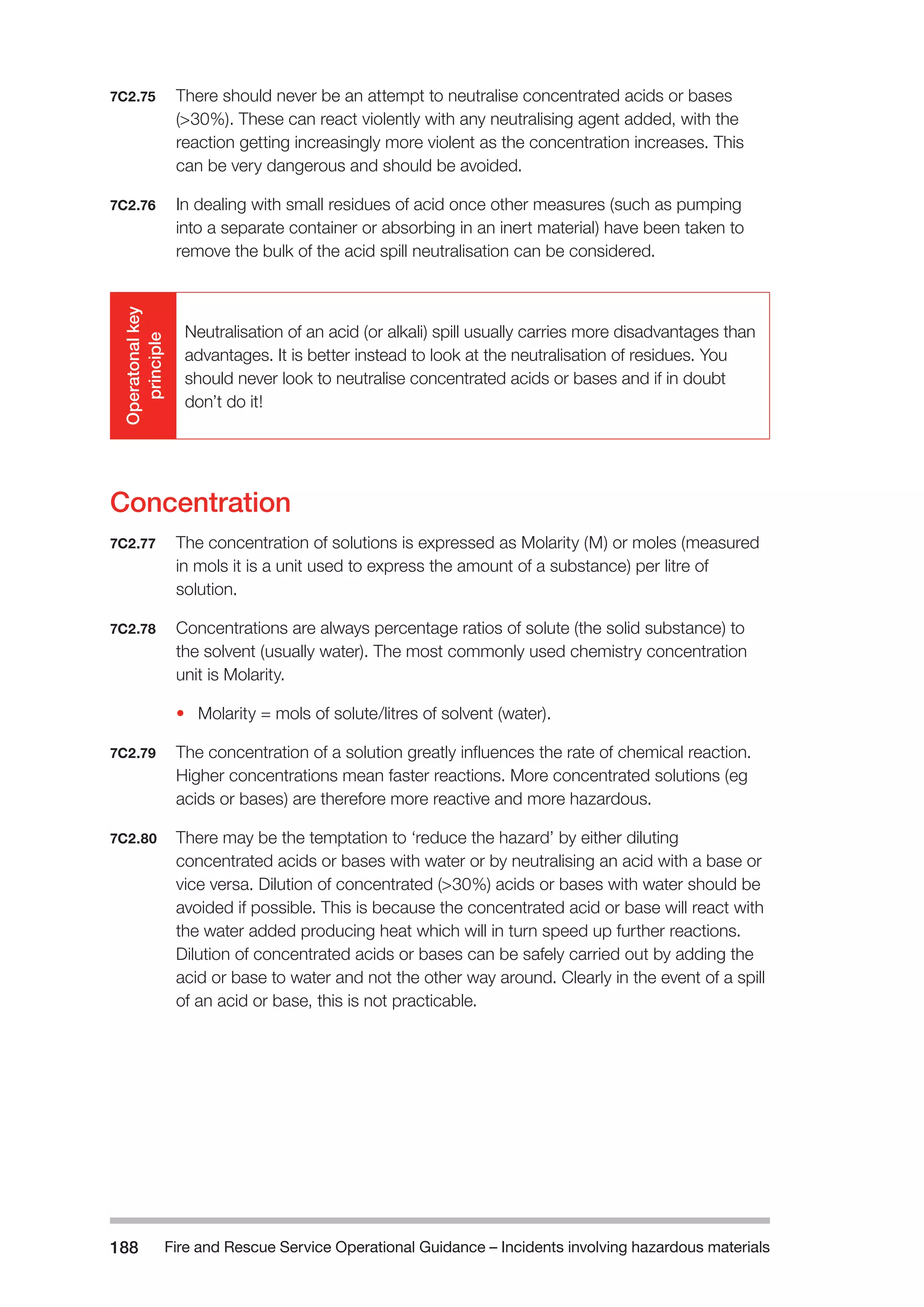

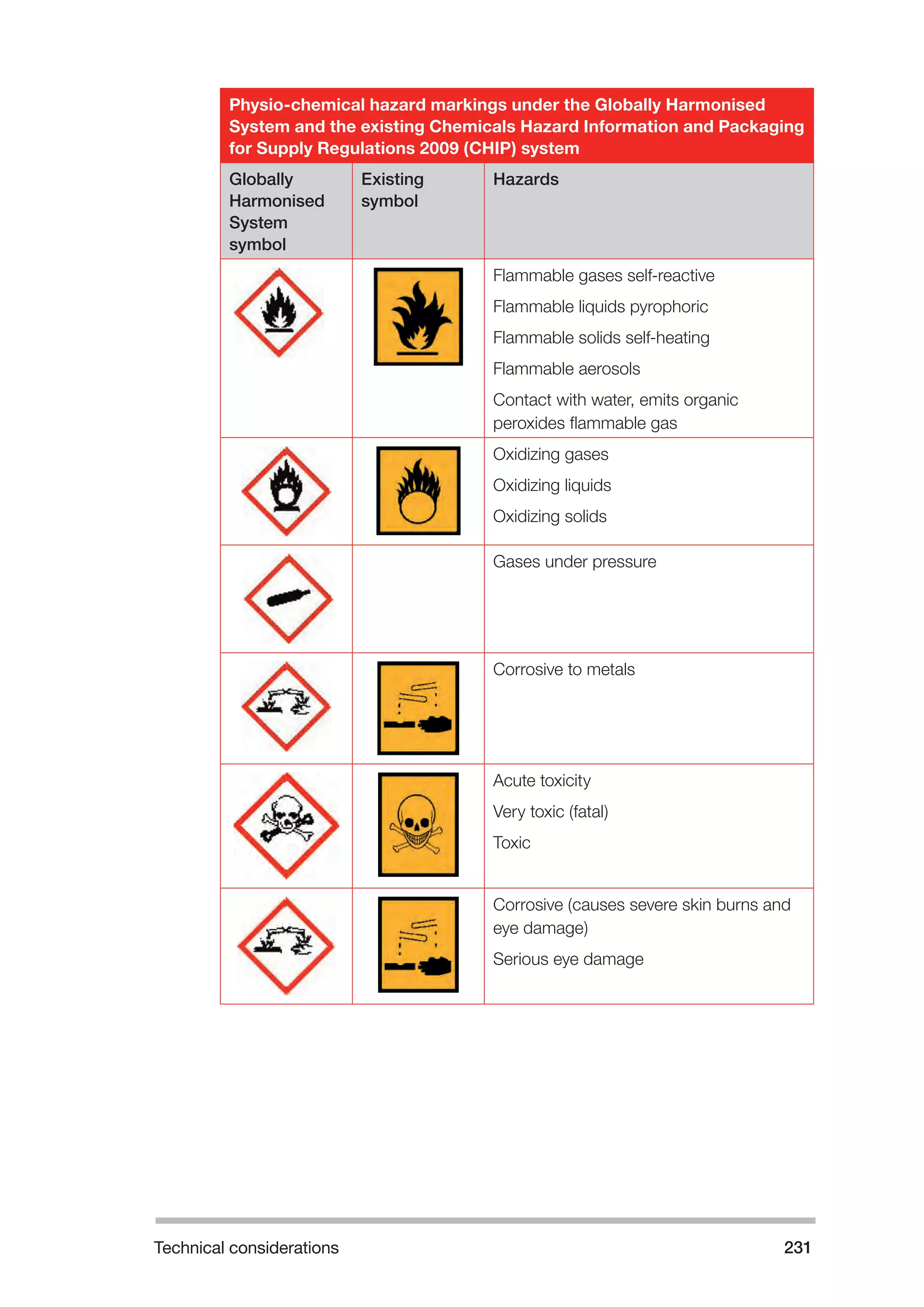

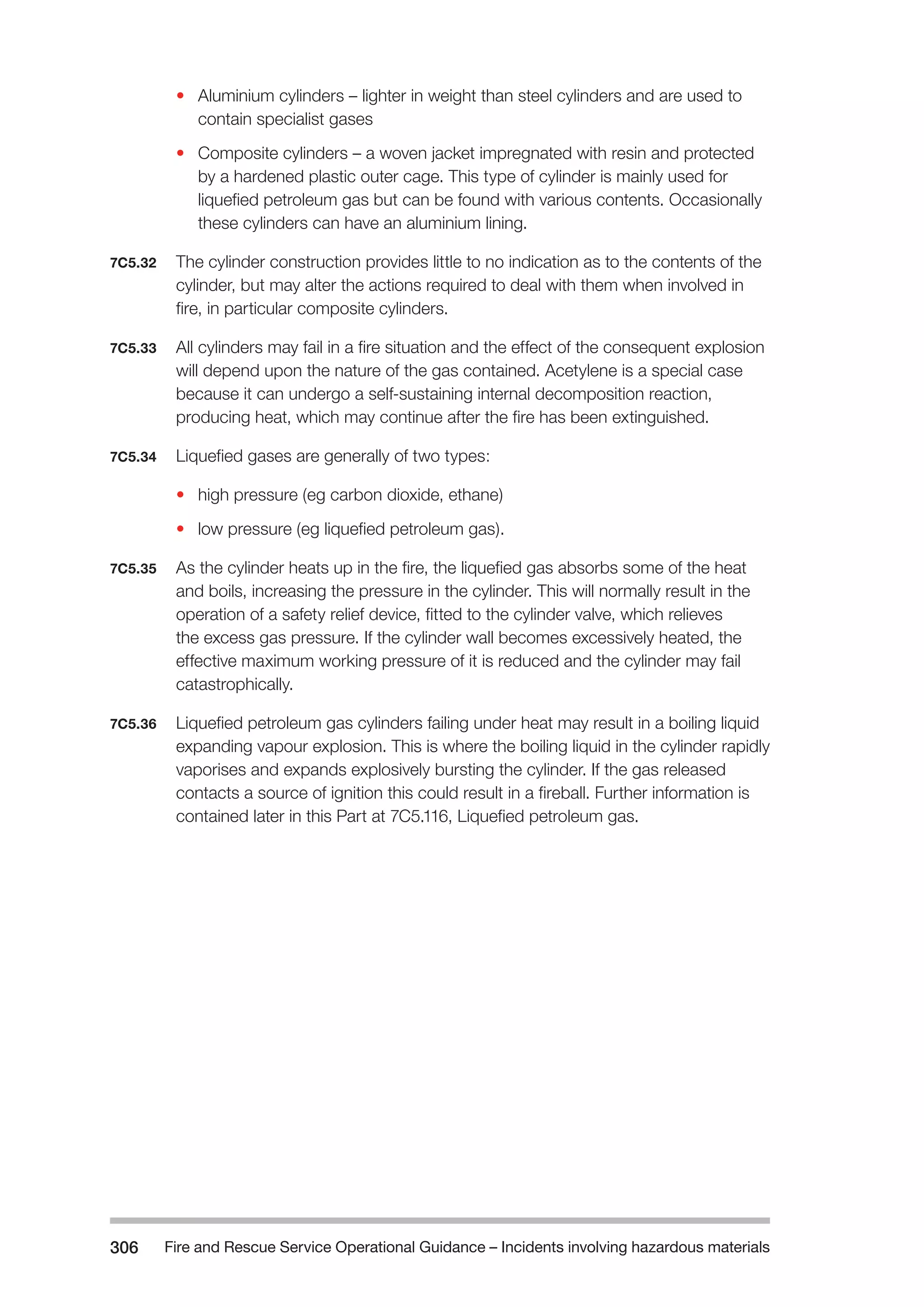

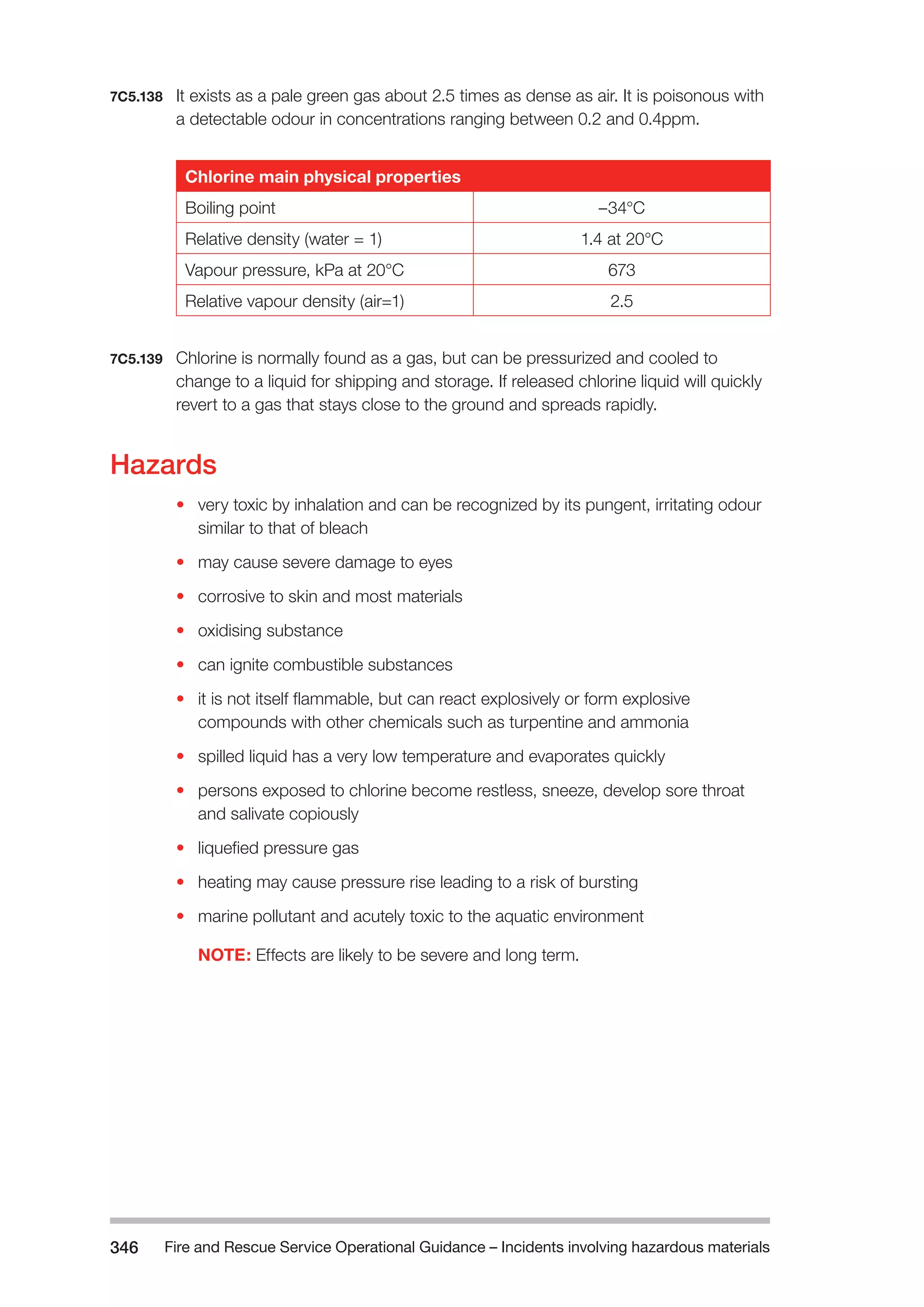

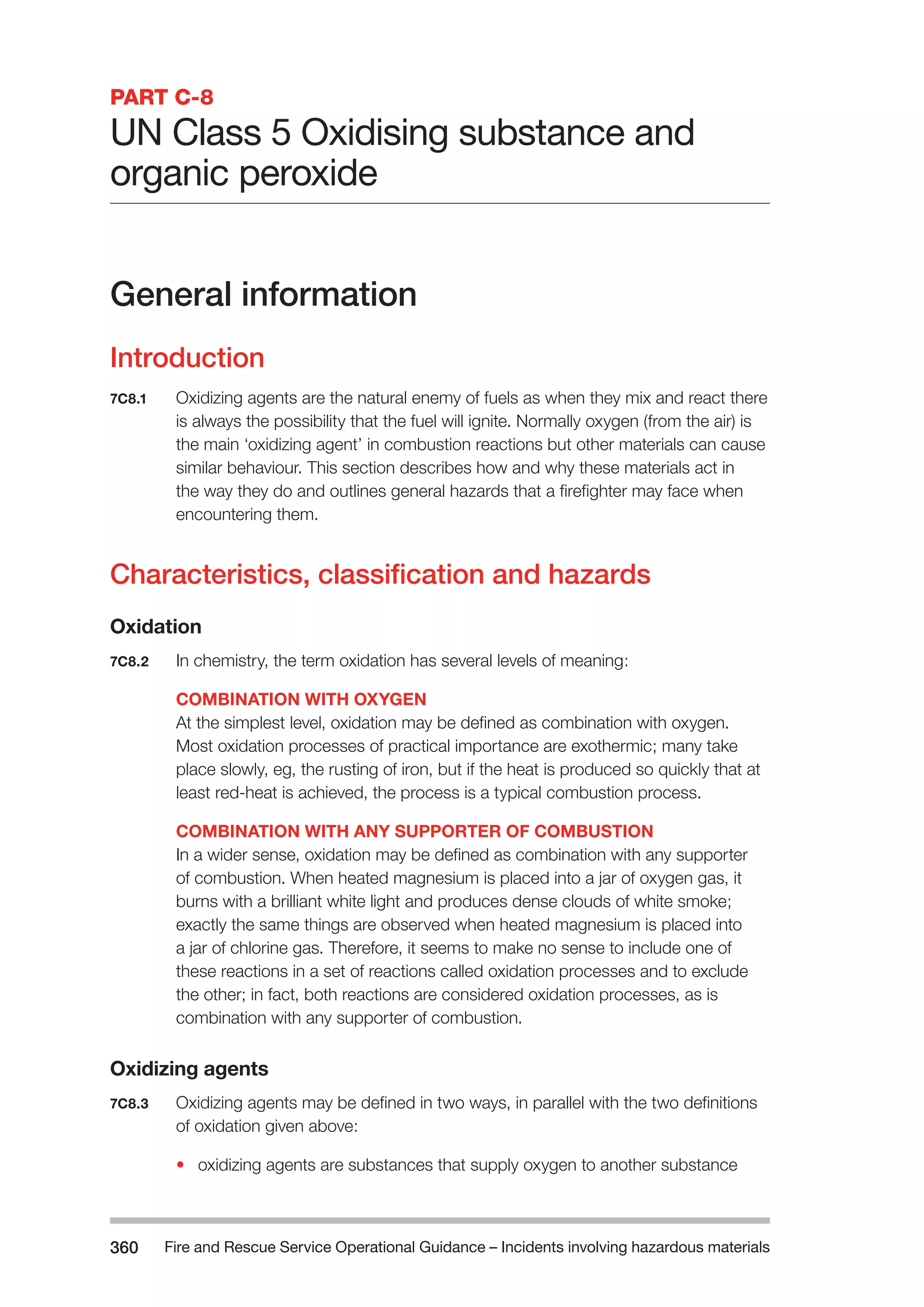

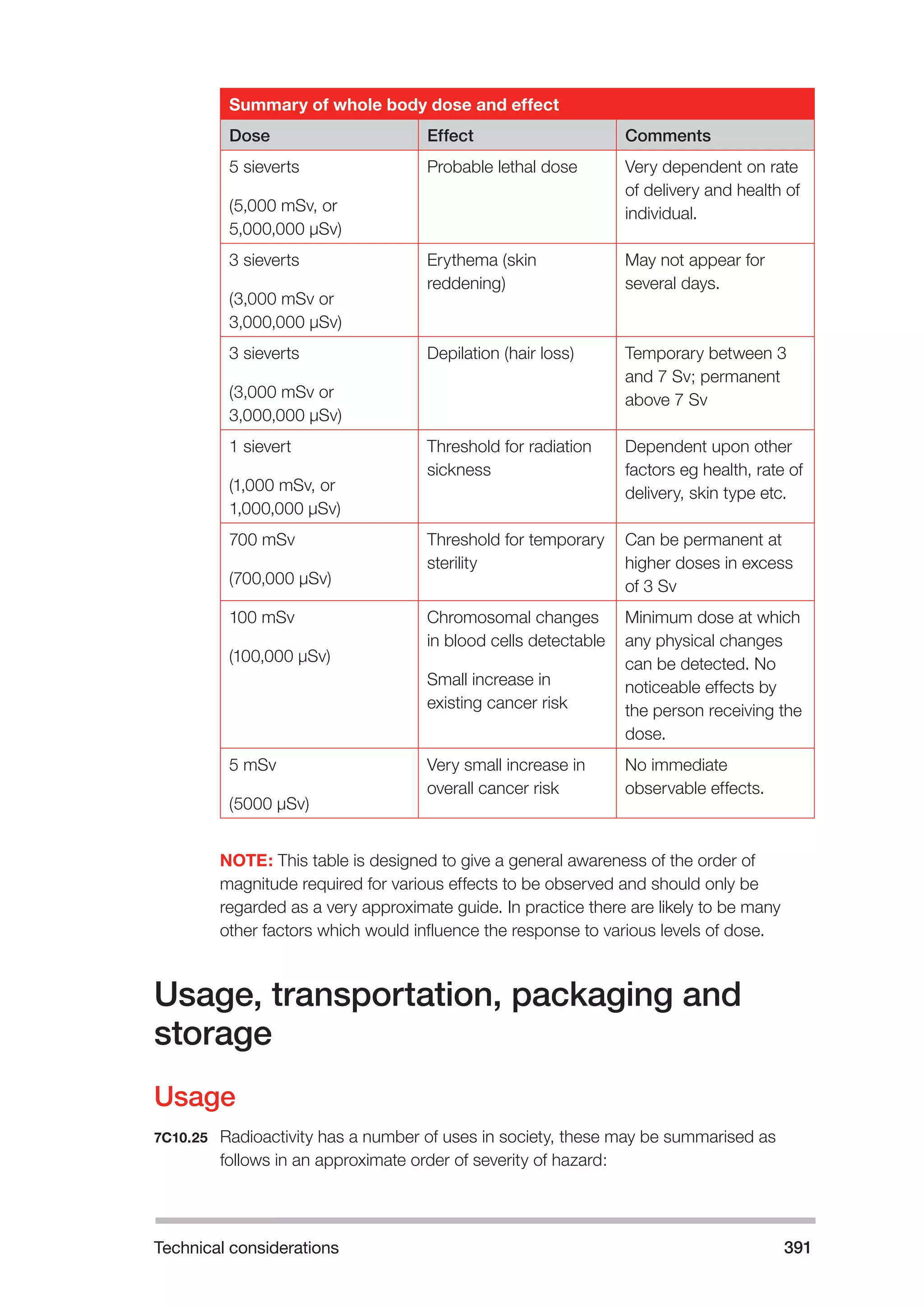

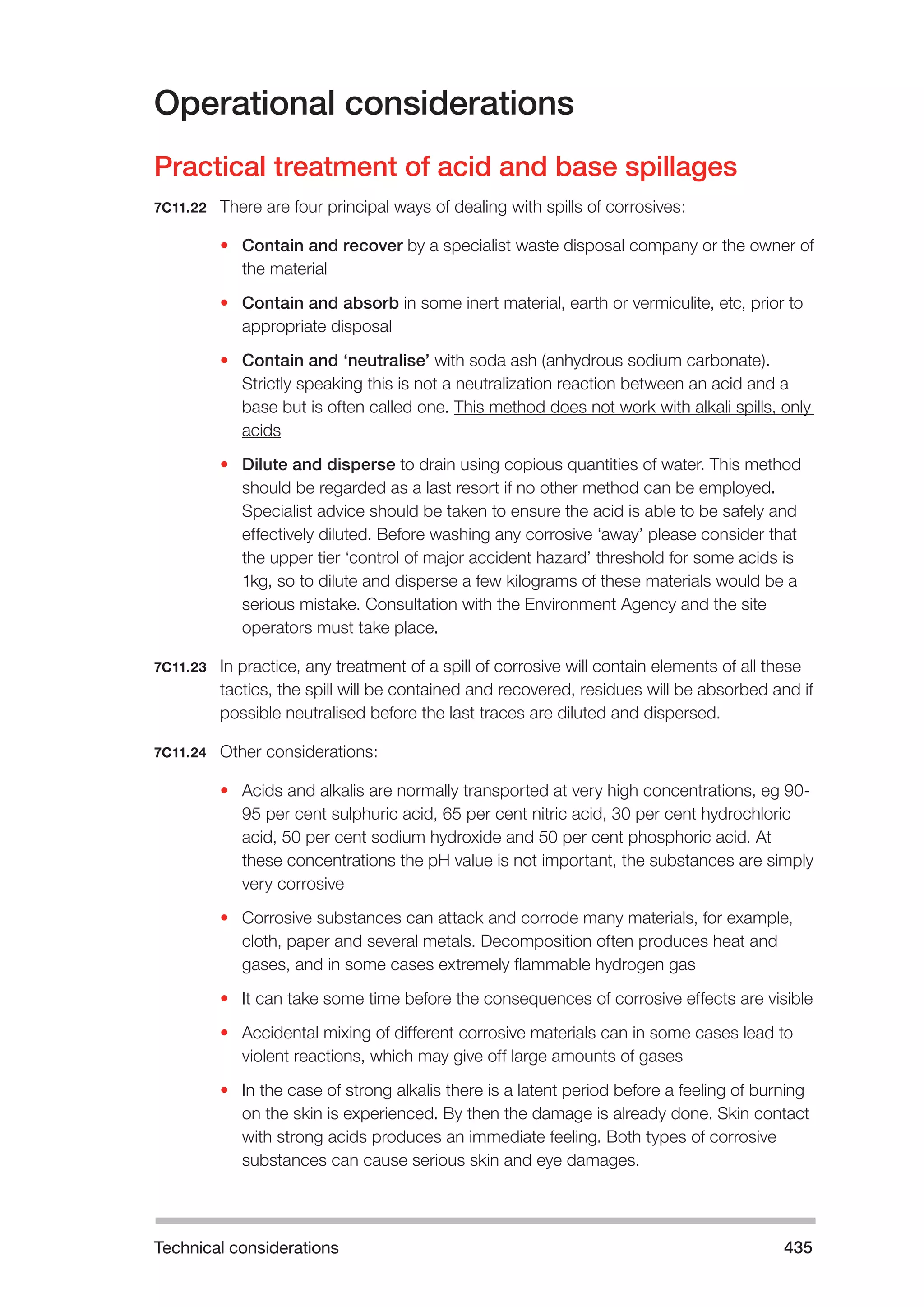

Standards applicable to chemical protective clothing – body protection

(in addition to EN340: 2003 – general requirements for protective clothing)

Number and title Comments

**BS 8428:2004 – Protective clothing against

liquid chemicals. Chemical protective suits with

liquid-tight connections between different parts

of the clothing for emergency teams (type 3-ET

equipment)

**see note 2 below this table

Suitable when the 2nd character

of EAC = ‘P’, ‘R’, ‘W’ or ‘X’

plus either limited use or reusable

EN 14605:2005 – Protective clothing against

liquid chemicals. Performance requirements for

chemical protective clothing with liquid tight

(Type 3) or spray-tight (Type 4) connections,

including items providing protection to parts of

the body only (Types PB[3] and PB[4])

Suitable when the 2nd character

of EAC = ‘P’, ‘R’, ‘W’ or ‘X’ (Type 3

only)

– Type 3 liquid tight connections for

whole body

– Type 4 spray tight connections for

whole body

– PB[3] liquid tight partial body

protection

– PB[4] spray tight partial body

protection

EN 943-1:2002 – Protective clothing against

liquid chemicals. Ventilated and non-ventilated

gas tight (Type 1) and non gas tight (Type 2)

chemical protective suits which retain positive

pressure to prevent ingress of dusts liquids and

vapours

1a gas tight with breathing apparatus

inside

1b gas tight with breathing

apparatus outside

1c gas tight air fed suit

2 non gas tight air fed suit

EN 13034:2005 – Protective clothing against

liquid chemicals. Chemical protective clothing

offering limited protection against liquid

chemicals (type 6 and type PB [6] equipment)

Type 6 – full body

Type PB[6] – partial body

EN 13982-1:2004 – Protective clothing for use

against solid particulates – Part 1: Performance

requirements for chemical protective clothing

providing protection to the full body against

airborne solid particulates (type 5 clothing)

EN 14126:2003 – Protective clothing.

Performance requirements and tests methods

for protective clothing against infective agents

EN 469:2005 – Protective clothing for firefighters.

Performance requirements for protective clothing

for firefighting (Superseded EN 469:1995)

Additional requirements may be met

for penetration by liquid chemicals

Suitable for EACs ‘S’, ‘T’, ‘Y’, and

‘Z’ with SCBA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7rbqzs77riklyjybirhl-signature-8ae49c26427c42a89a6d4352195b02a6095bd9fa5df6c0500639463b6450e515-poli-140828111115-phpapp02/75/The-Fire-and-Rescue-Service-Books-is-a-guidance-for-organize-a-safe-system-of-work-on-the-incident-ground-with-hazardous-materials-482-2048.jpg)