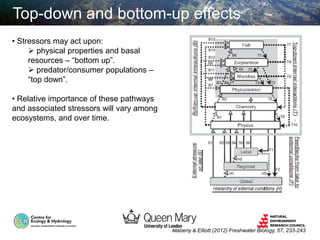

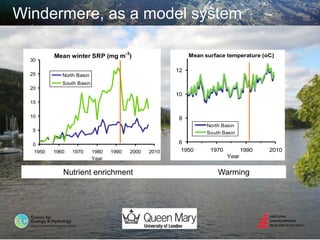

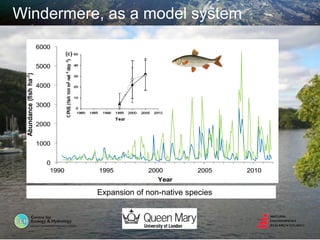

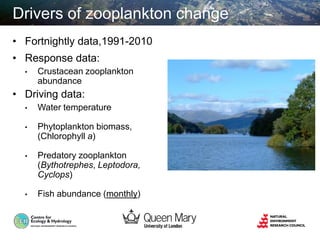

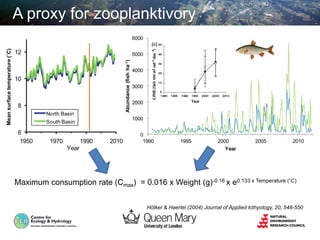

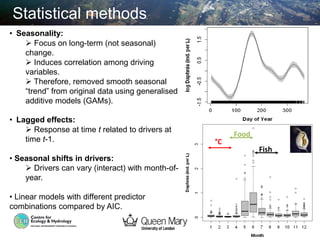

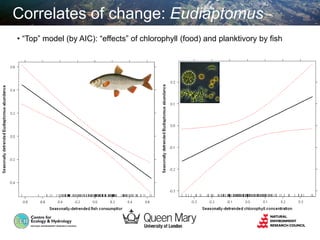

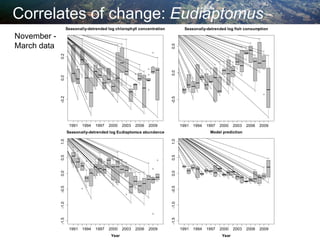

This document summarizes a study analyzing the long-term responses of crustacean zooplankton populations in Windermere, England to multiple stressors including climate change, eutrophication, and the expansion of non-native fish species. The study used statistical models to analyze long-term monitoring data from 1991-2010 on zooplankton abundance, water temperature, phytoplankton biomass, predatory zooplankton, and fish abundance. For the species Eudiaptomus, the top model identified effects of increased chlorophyll (food) and planktivory by fish. While some population change was explained, much variation remained unexplained, warranting further exploration of