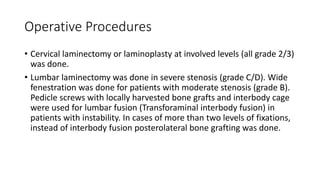

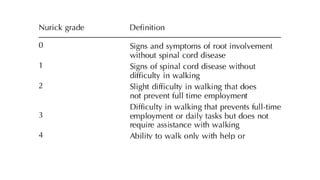

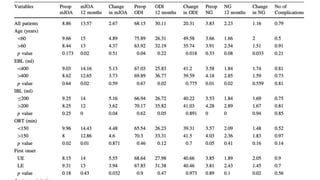

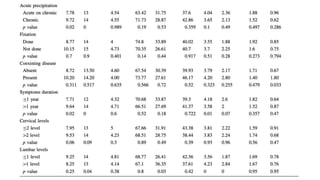

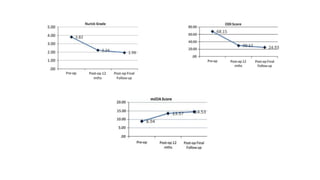

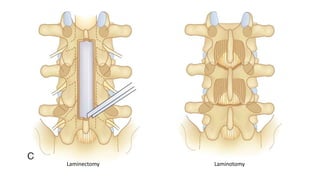

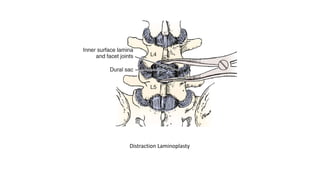

Tandem spinal stenosis is an infrequent condition where a patient has both cervical and lumbar spinal stenosis. The authors conducted a retrospective analysis of 53 patients who underwent single-stage surgery to decompress both regions simultaneously. Outcome measures showed significant improvements in disability and pain scores at over 1 year of follow up, demonstrating that a single-stage approach can provide good results for tandem spinal stenosis.