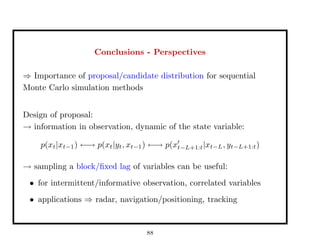

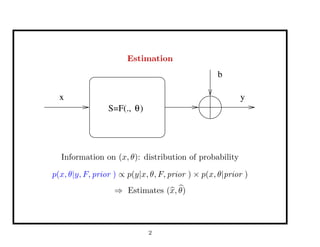

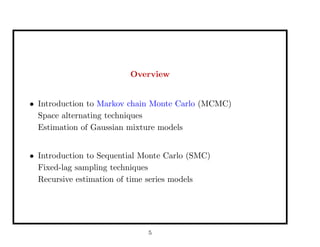

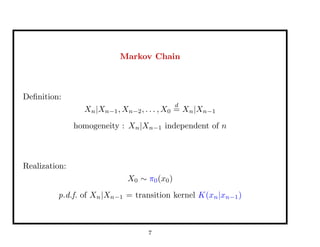

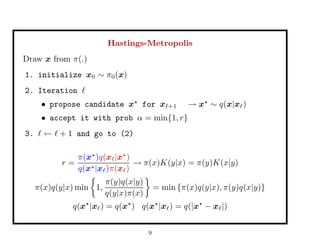

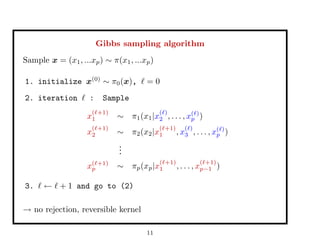

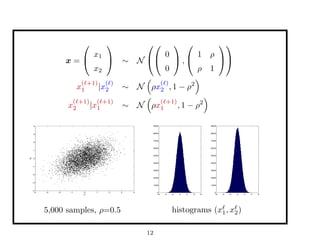

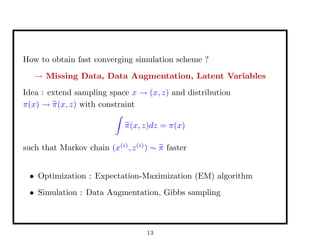

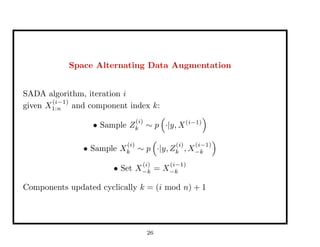

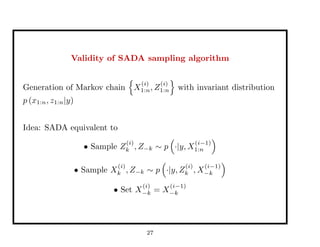

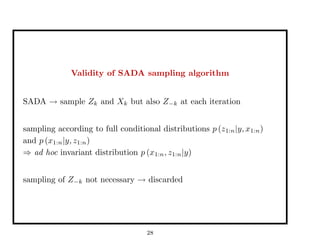

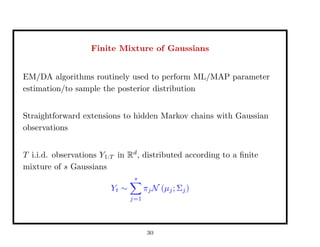

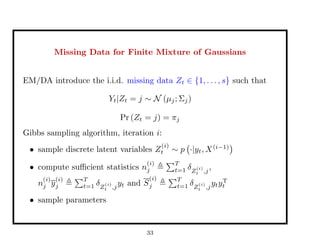

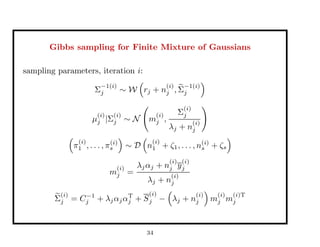

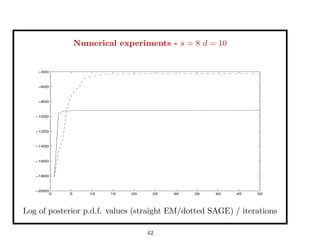

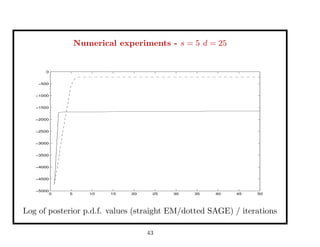

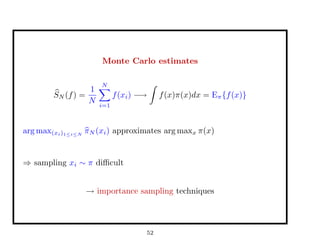

This document discusses recent advances in Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) methods. It introduces Markov chain and sequential Monte Carlo techniques such as the Hastings-Metropolis algorithm, Gibbs sampling, data augmentation, and space alternating data augmentation. These techniques are applied to problems such as parameter estimation for finite mixtures of Gaussians.

![Example

sample x ∼ p(x) ∝ 1

1+x2 20,000 iterations

x ∼ N(x , 0.12

)

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2

x 10

4

−5

0

5

10

15

−6 −4 −2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

acc. rate = 97%

x ∼ U[a,b]

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2

x 10

4

−15

−10

−5

0

5

10

15

−15 −10 −5 0 5 10 15

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

acc. rate = 26%

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65d692fa-f55c-4980-9d9c-58f5c1c6d0f3-160225000036/85/talk-MCMC-SMC-2004-10-320.jpg)

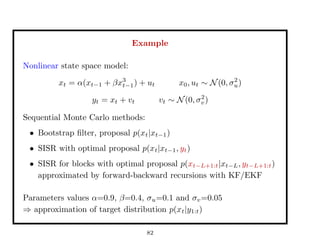

![Approximation of the target distribution

⇒ Effective Sample Size:

ESS =

1

N

i=1[w

(i)

t ]2

w(i)

= 1

N : ESS = N

pi(x_t)

x_t

w(i)

≈ 0 ∀i except one: ESS = 1

x_t

pi(x_t)

⇒ Resampling performed for ESS ≤ N

2 , N

10

83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65d692fa-f55c-4980-9d9c-58f5c1c6d0f3-160225000036/85/talk-MCMC-SMC-2004-83-320.jpg)