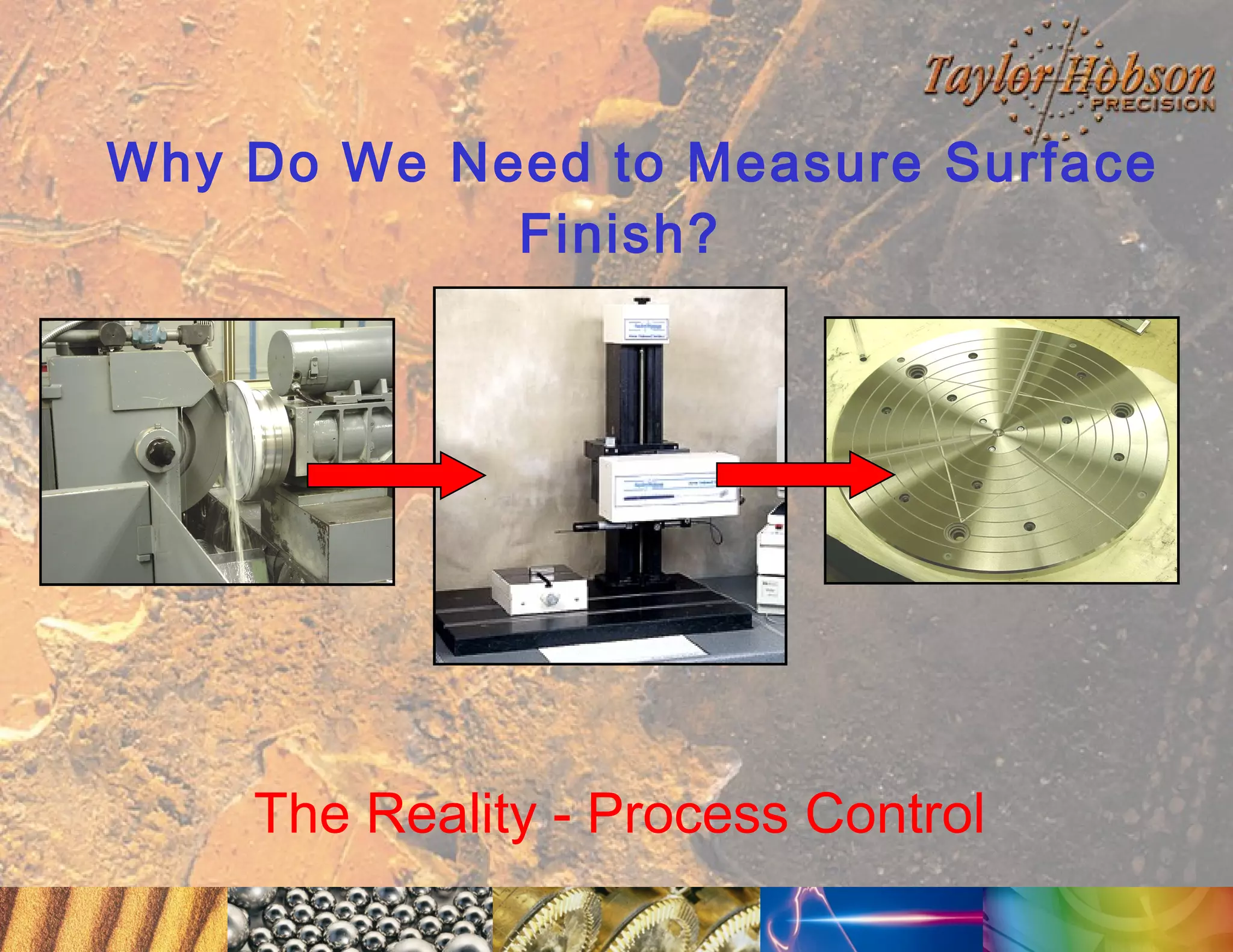

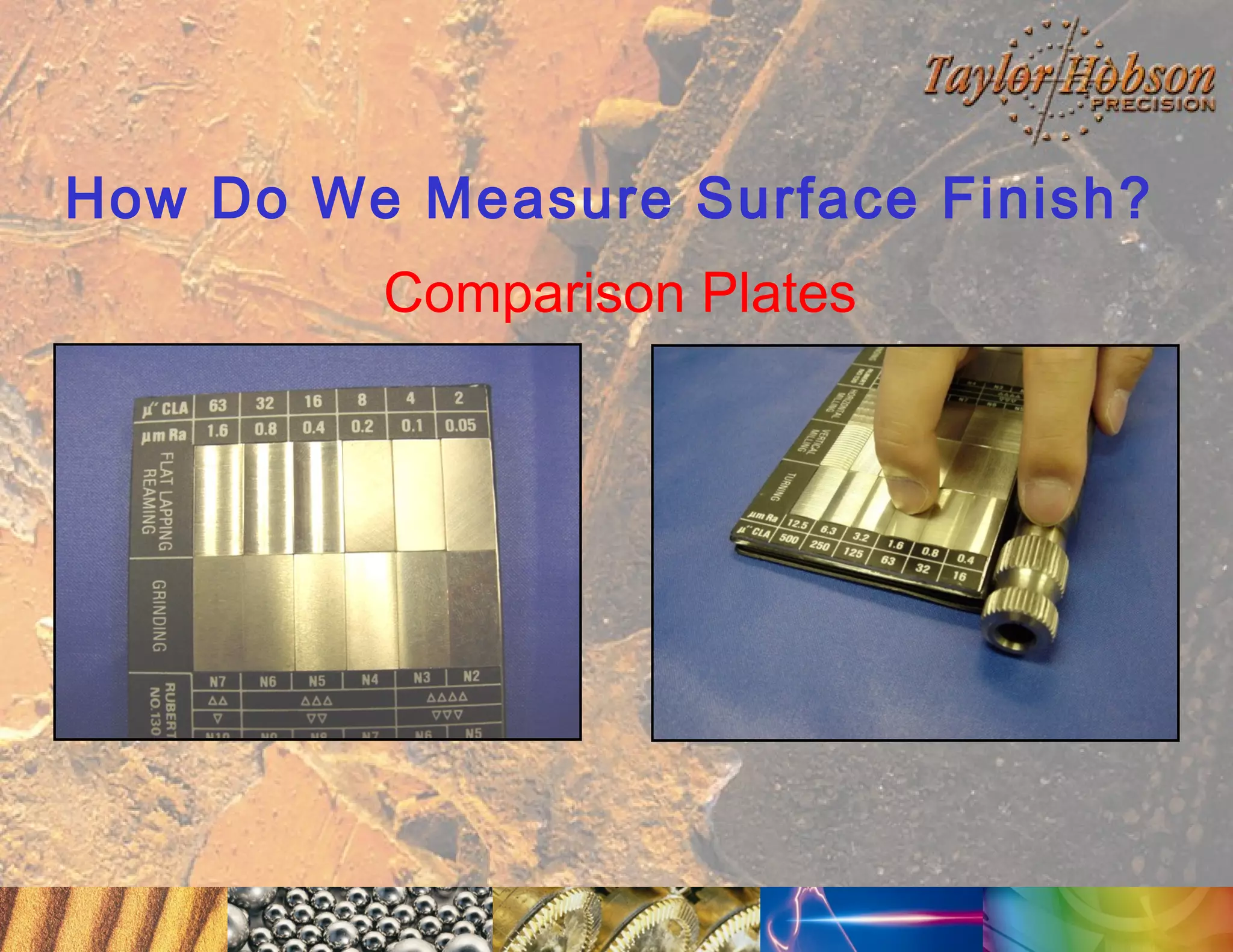

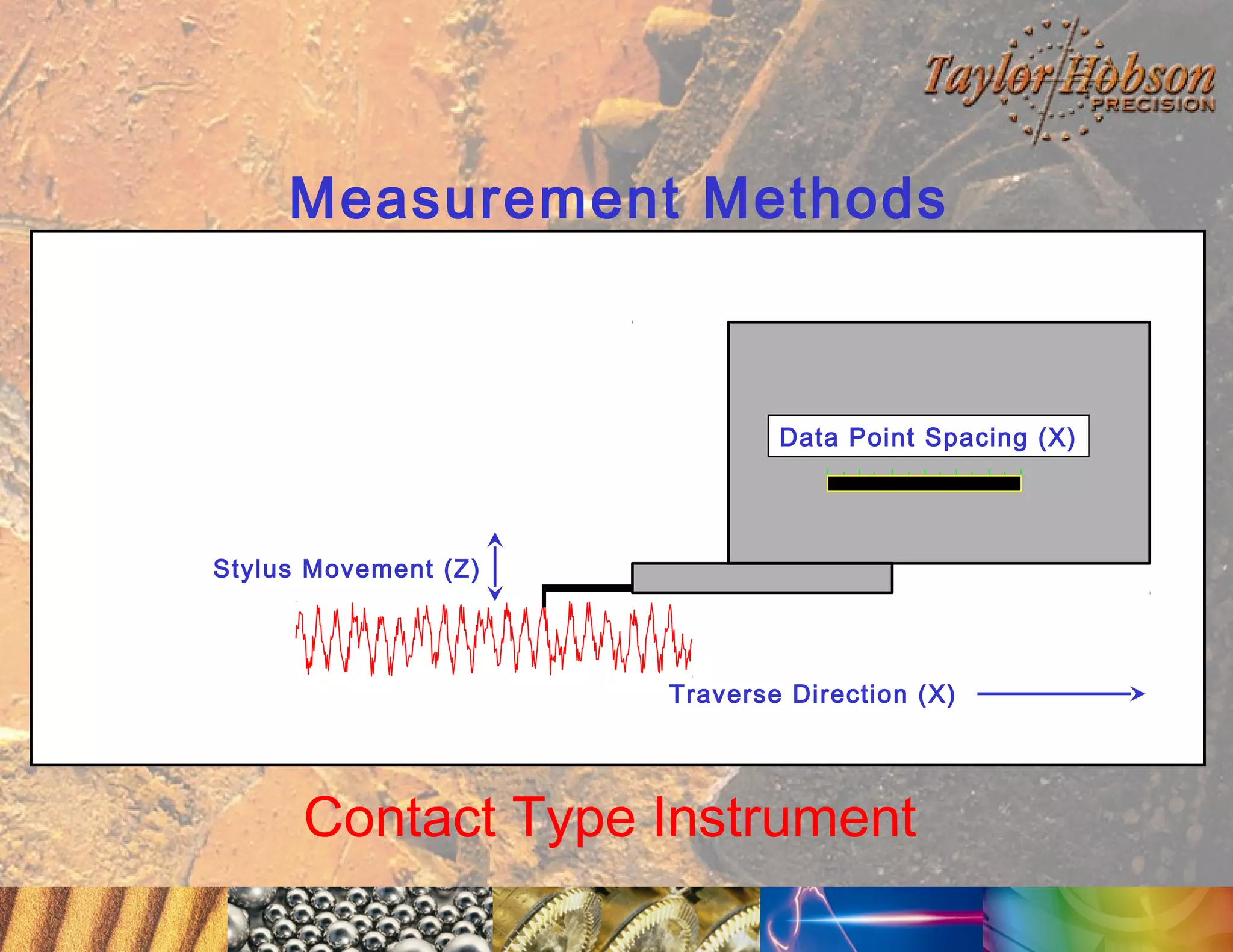

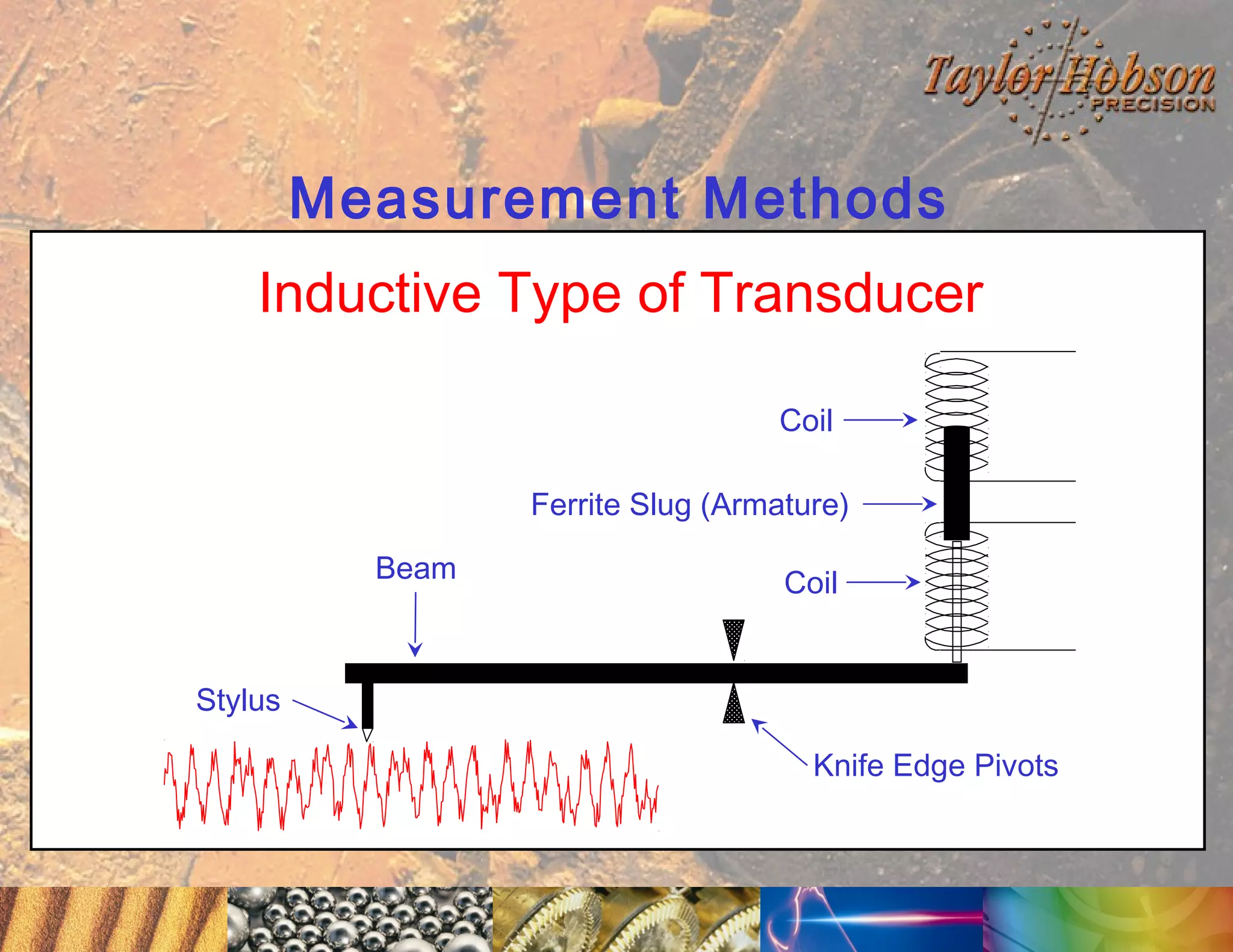

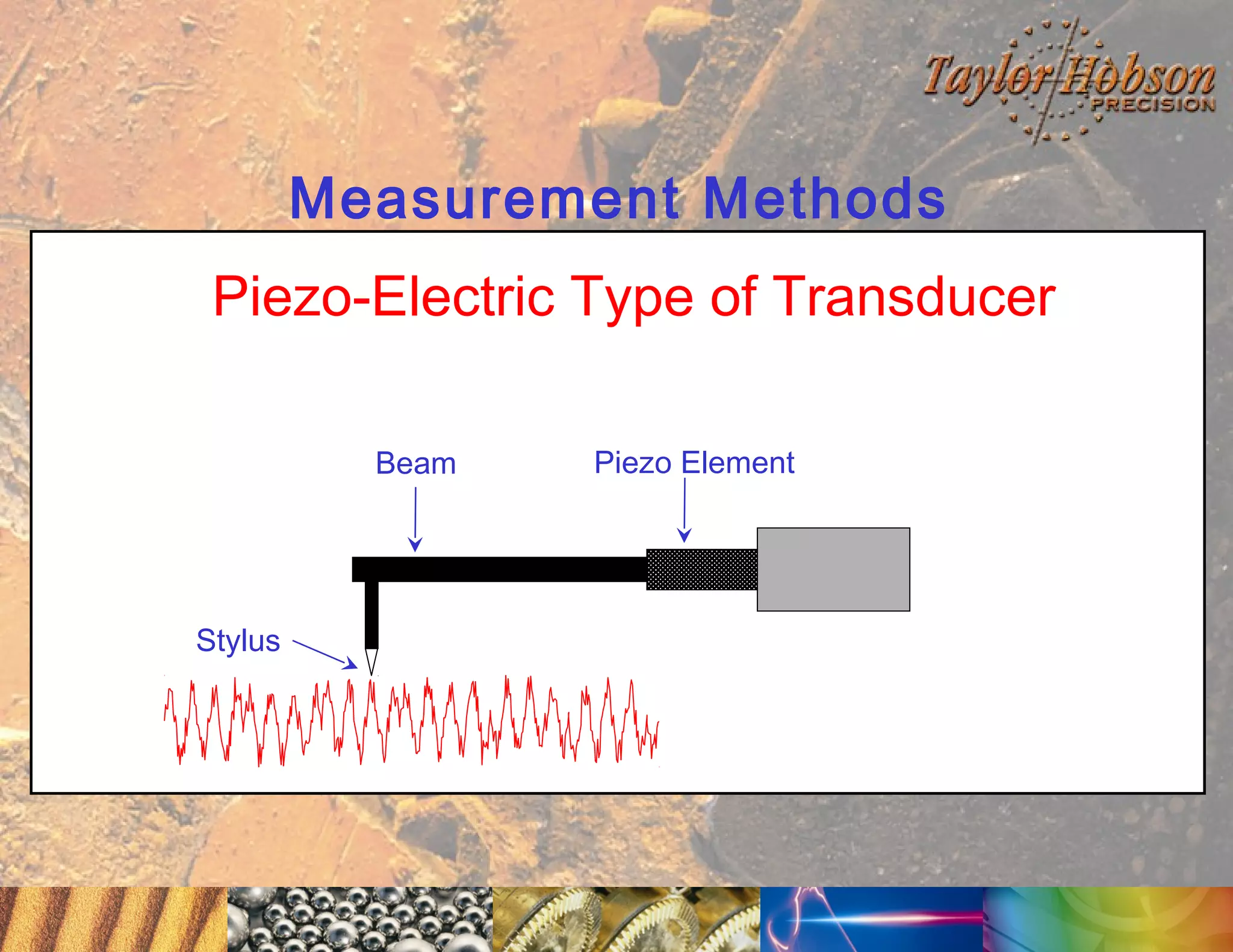

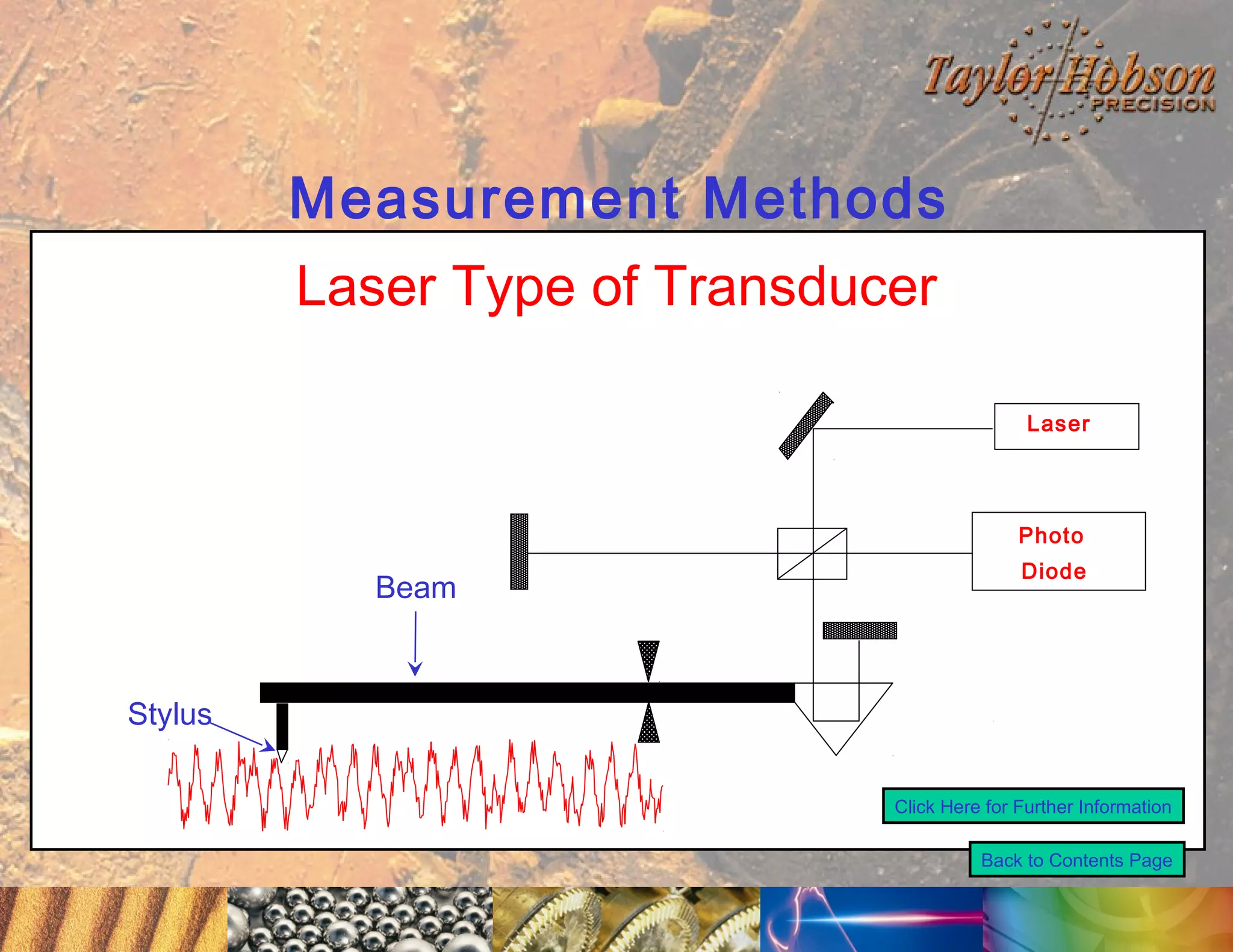

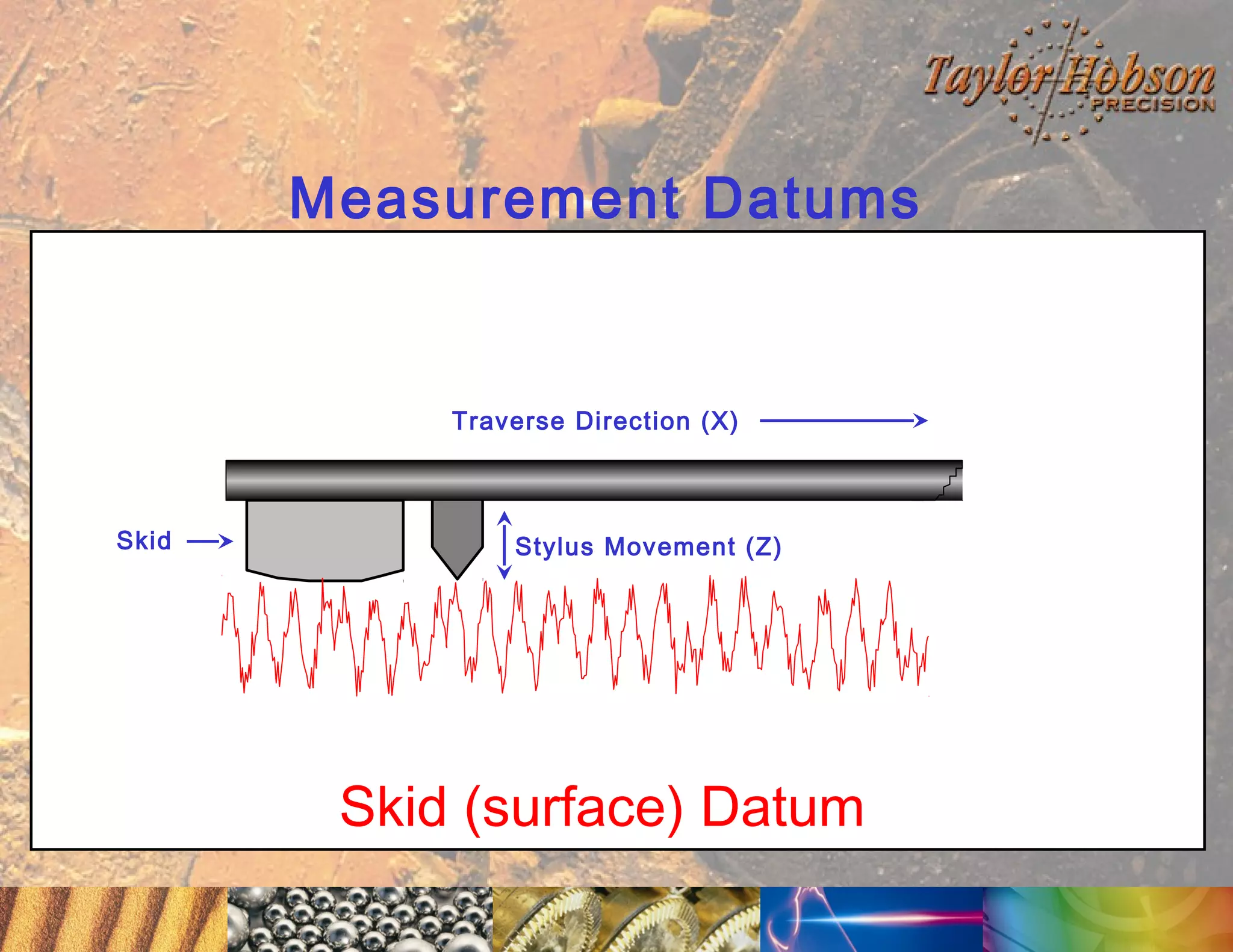

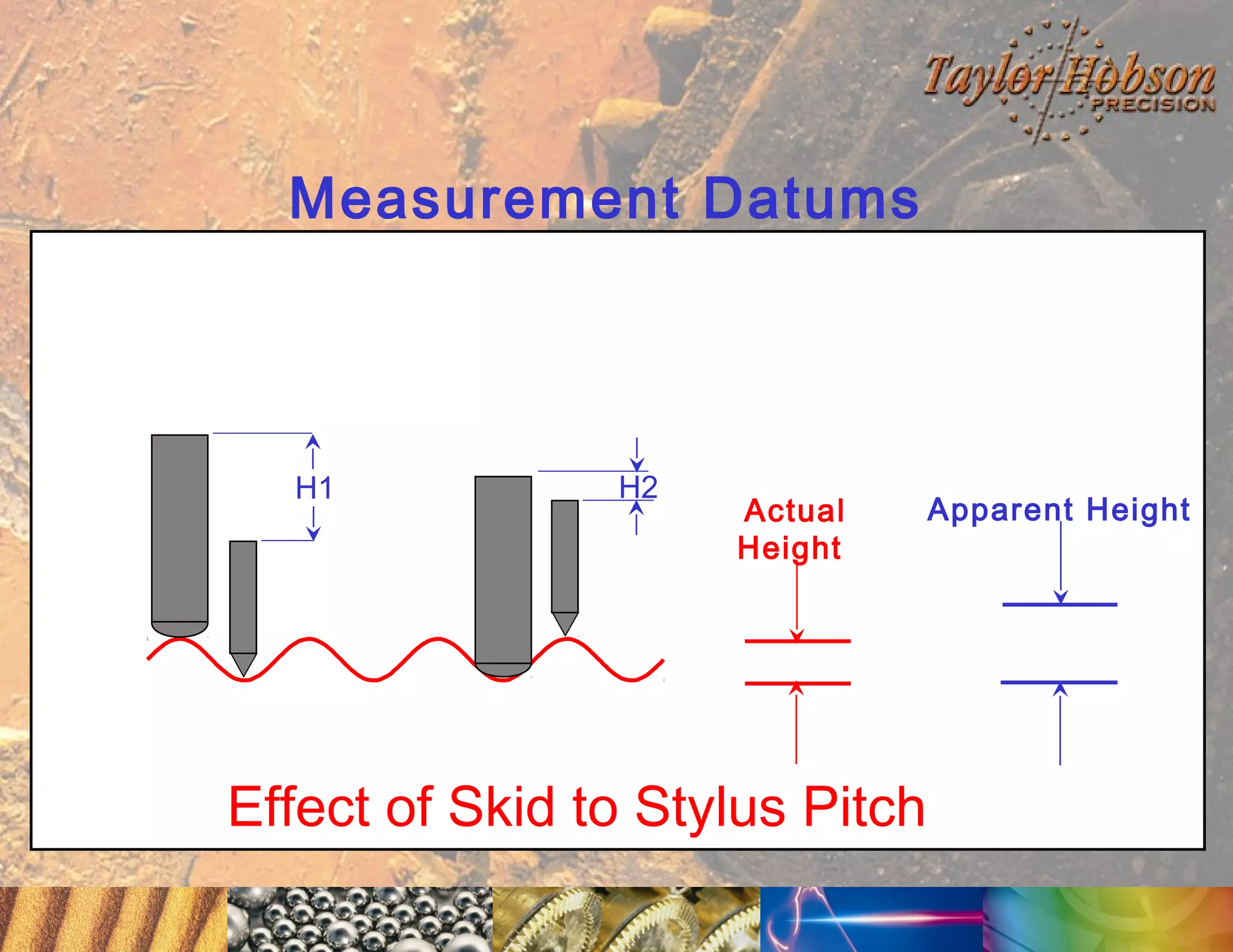

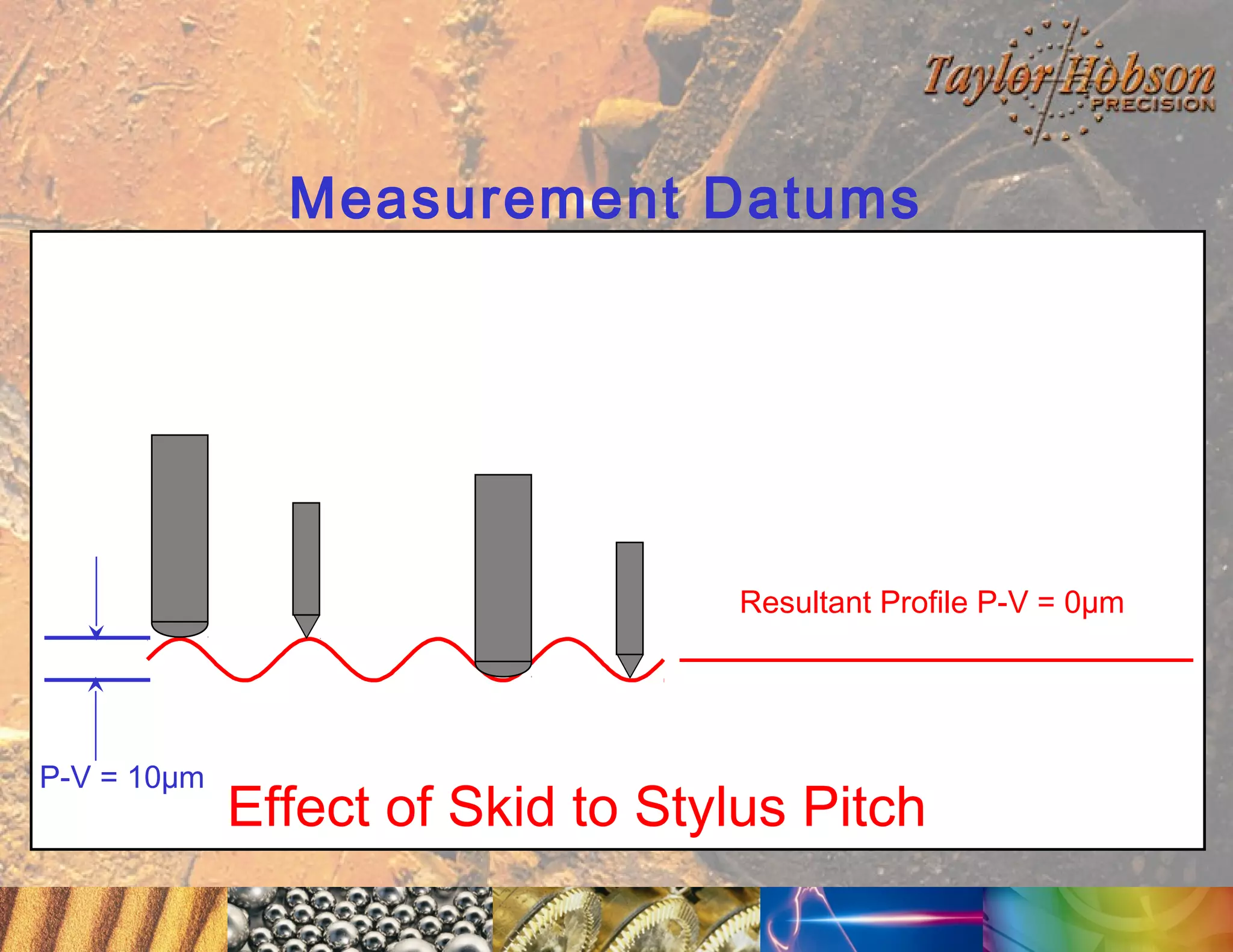

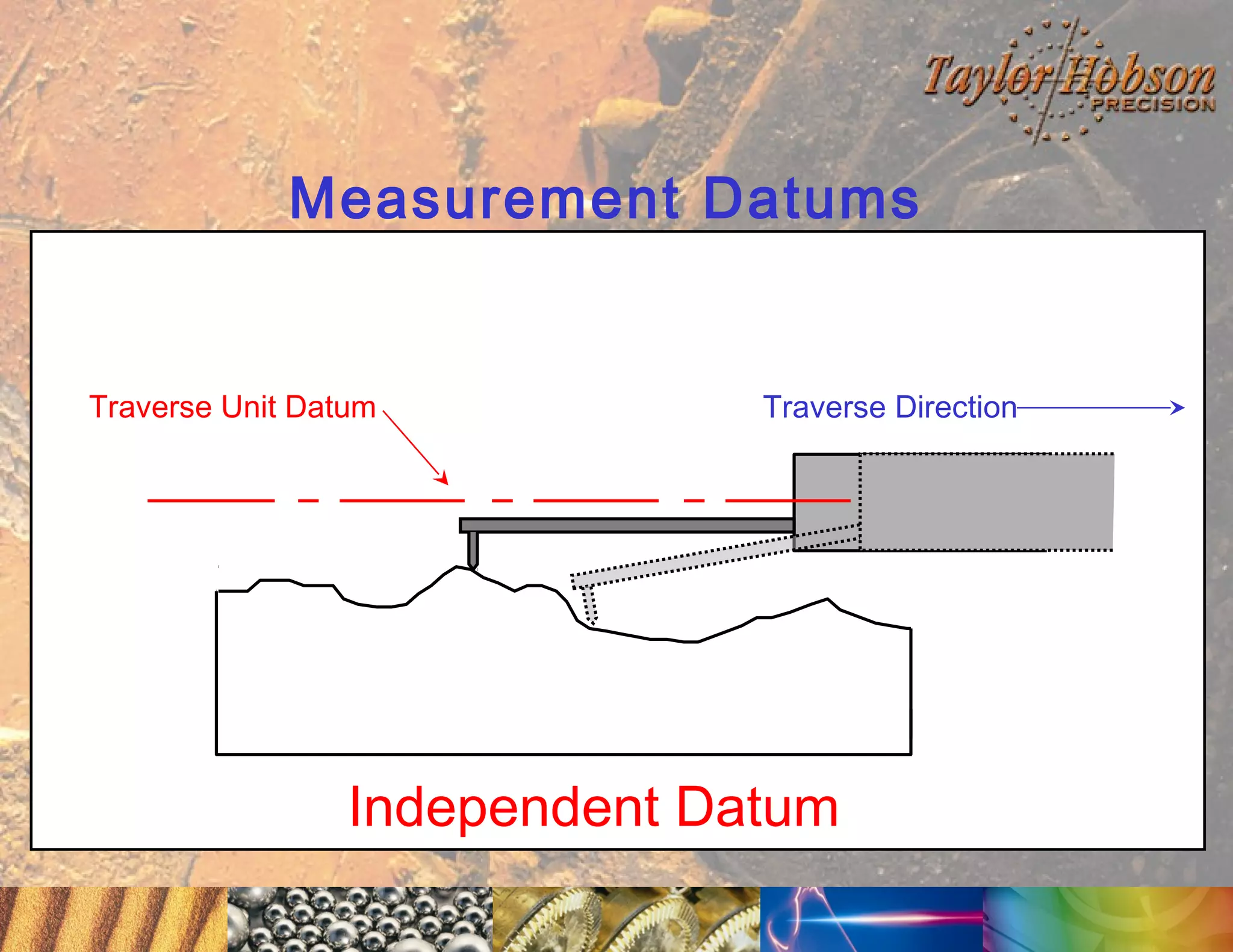

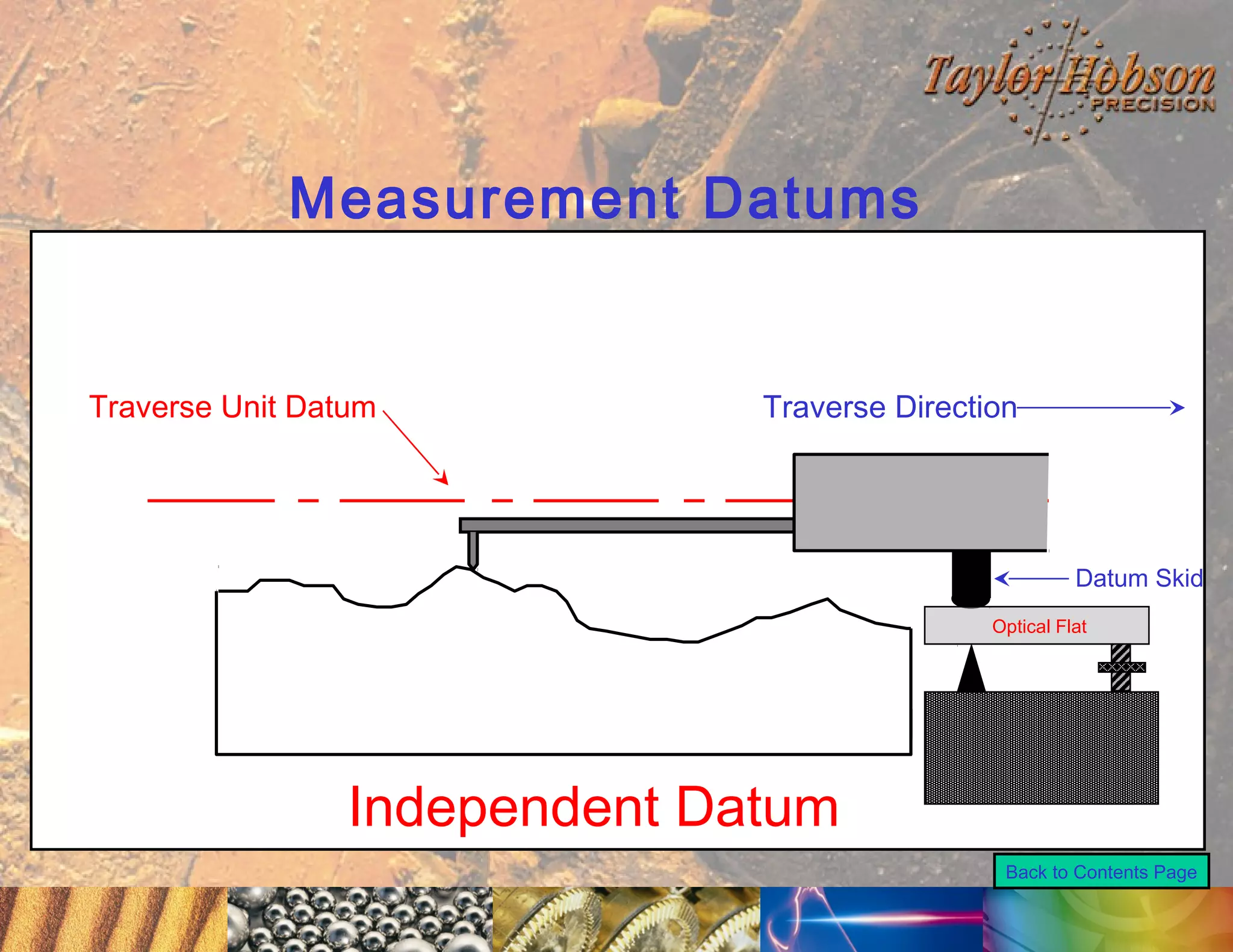

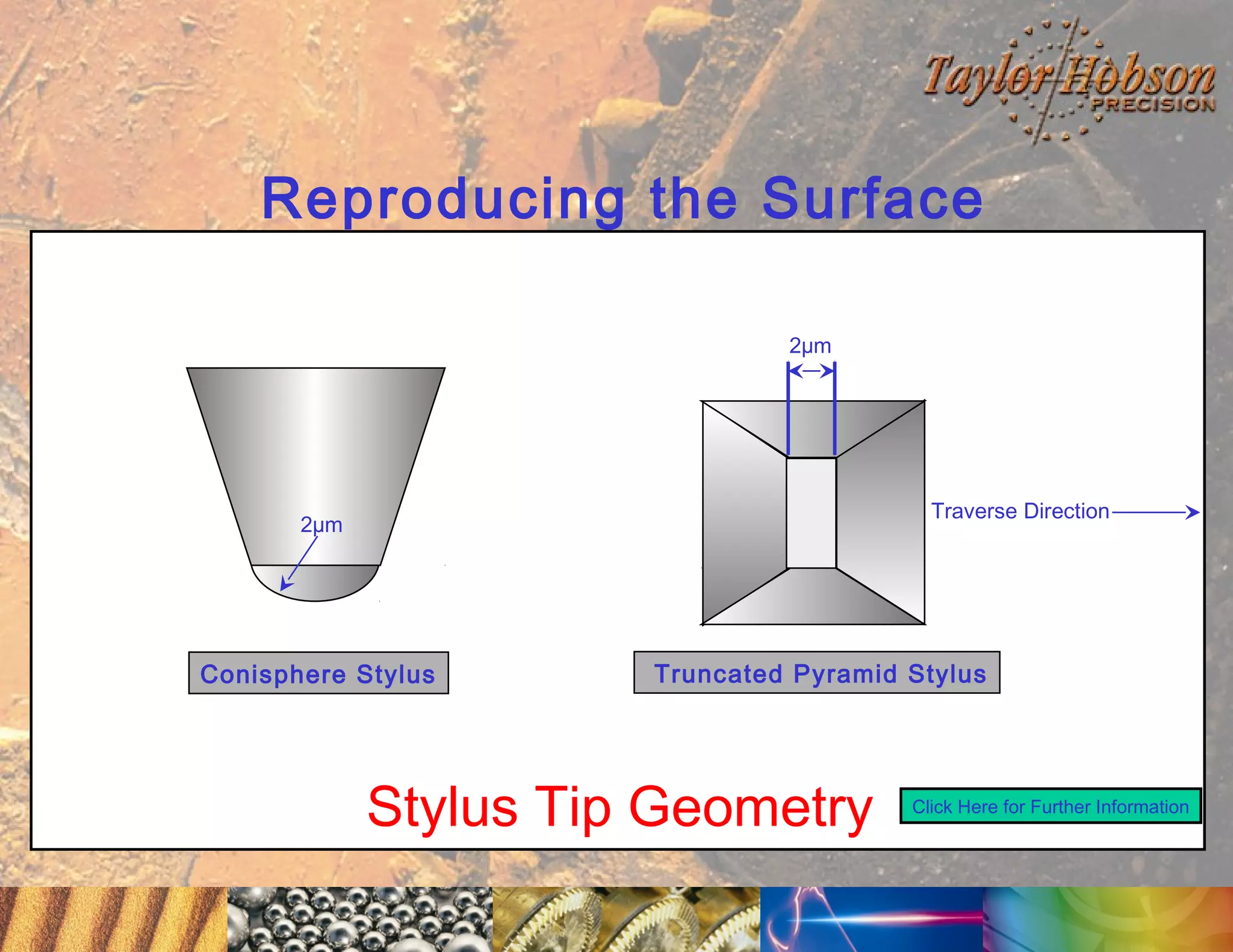

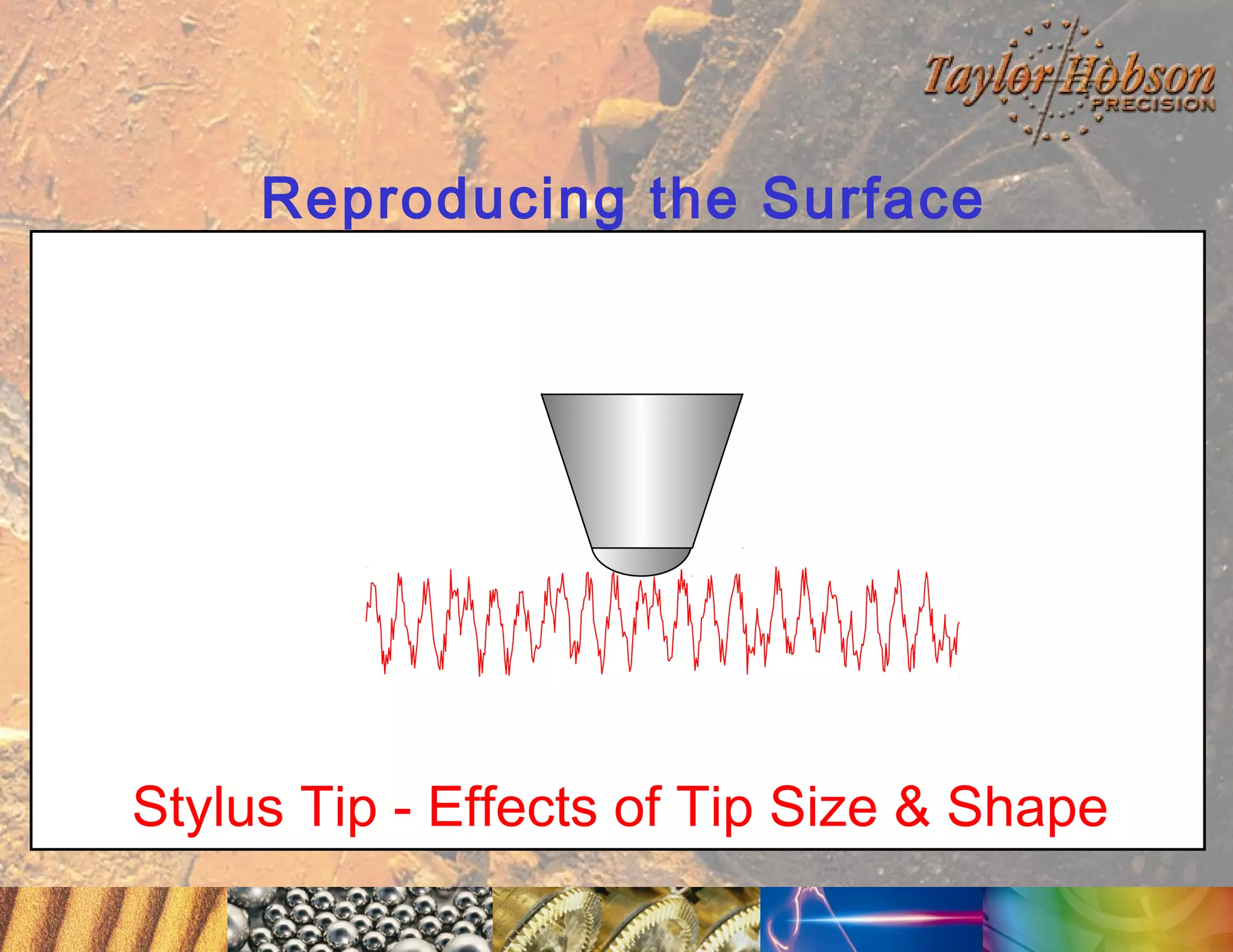

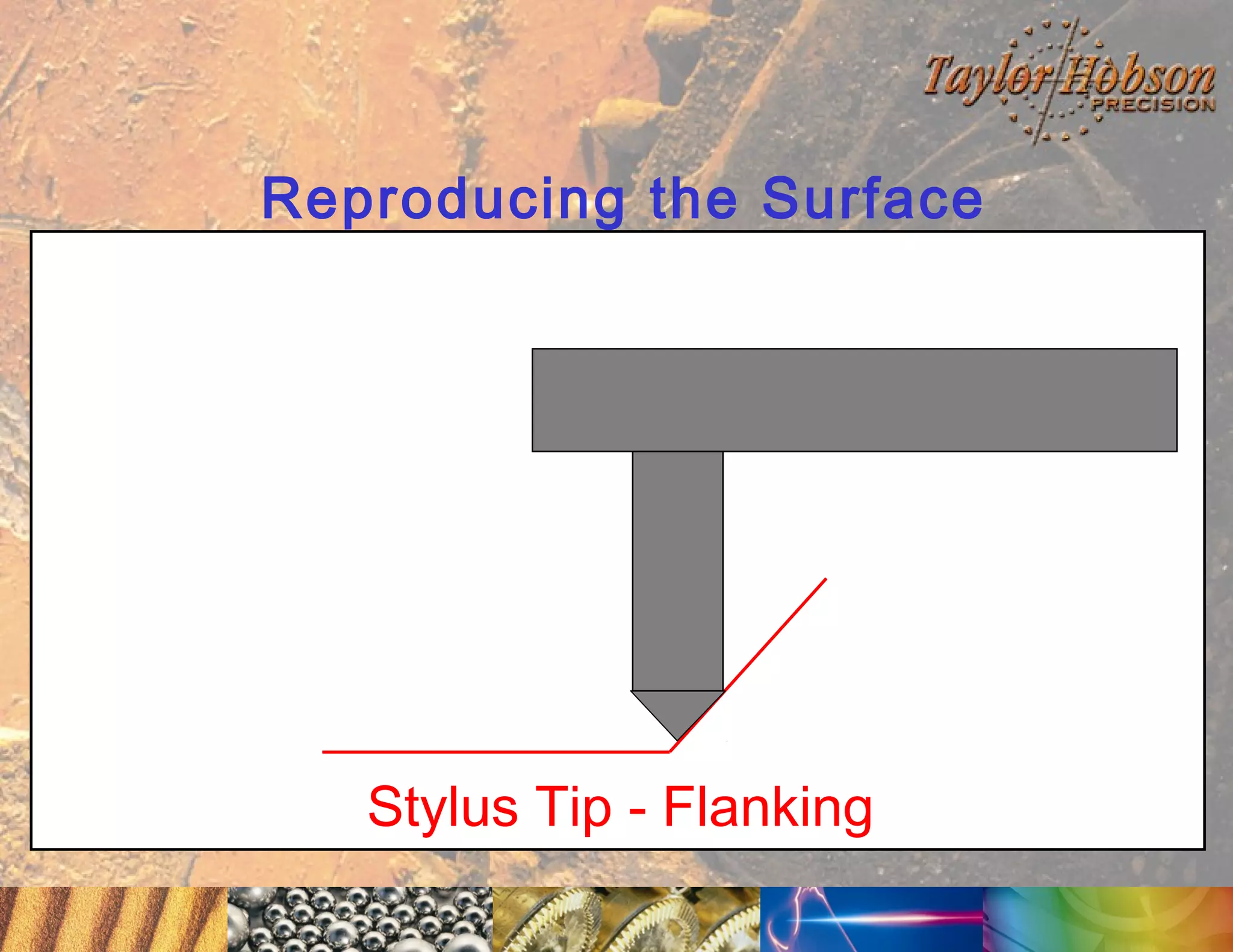

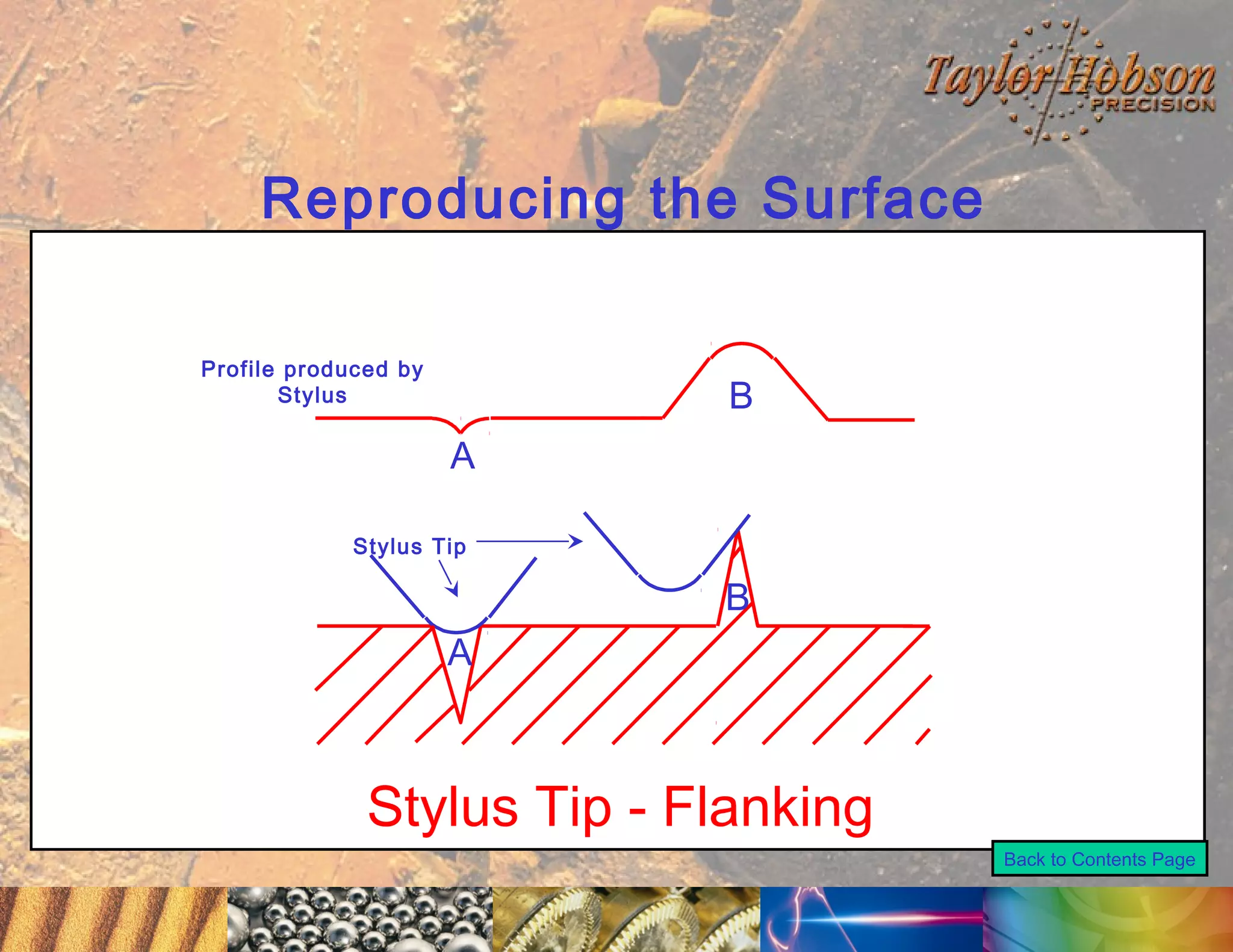

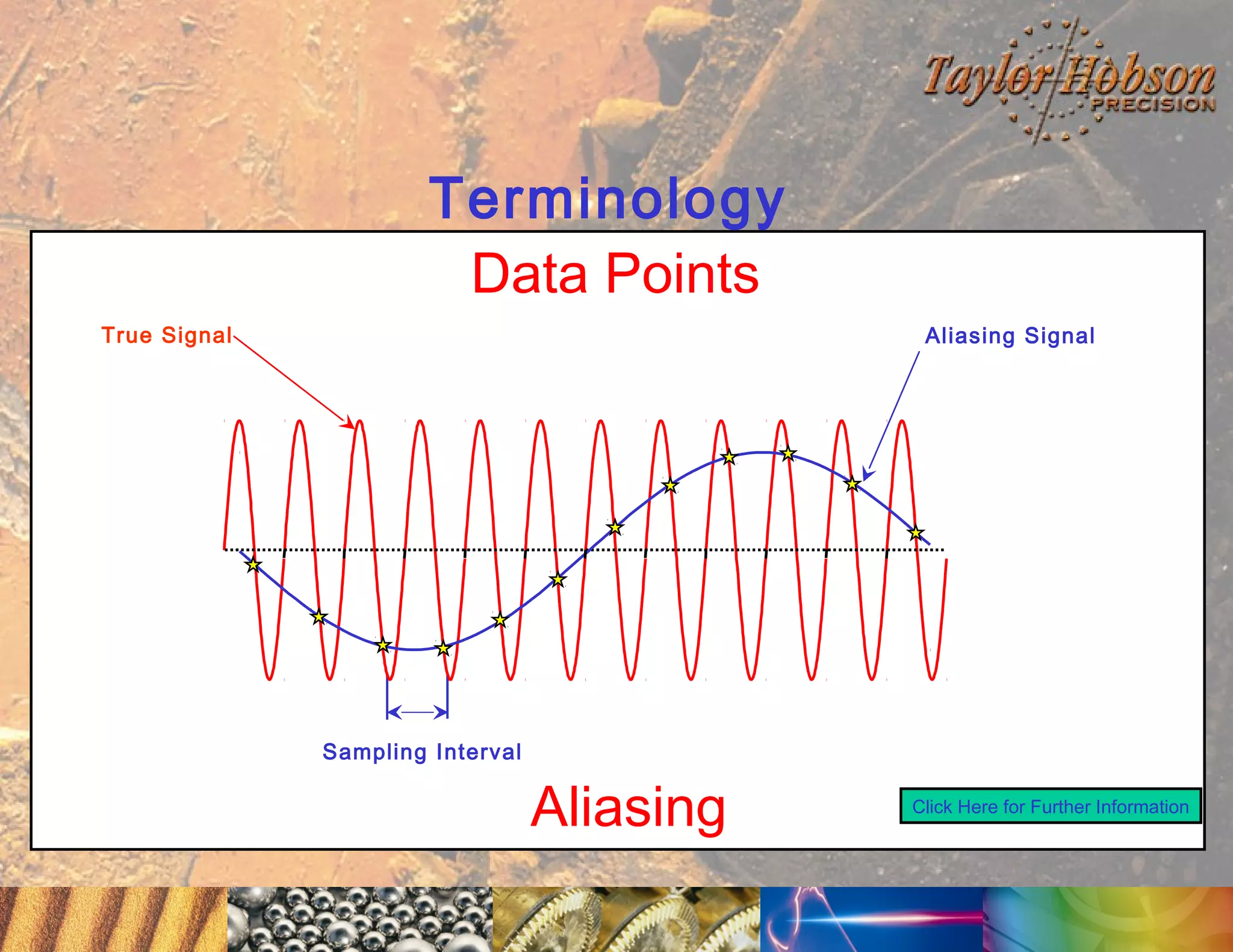

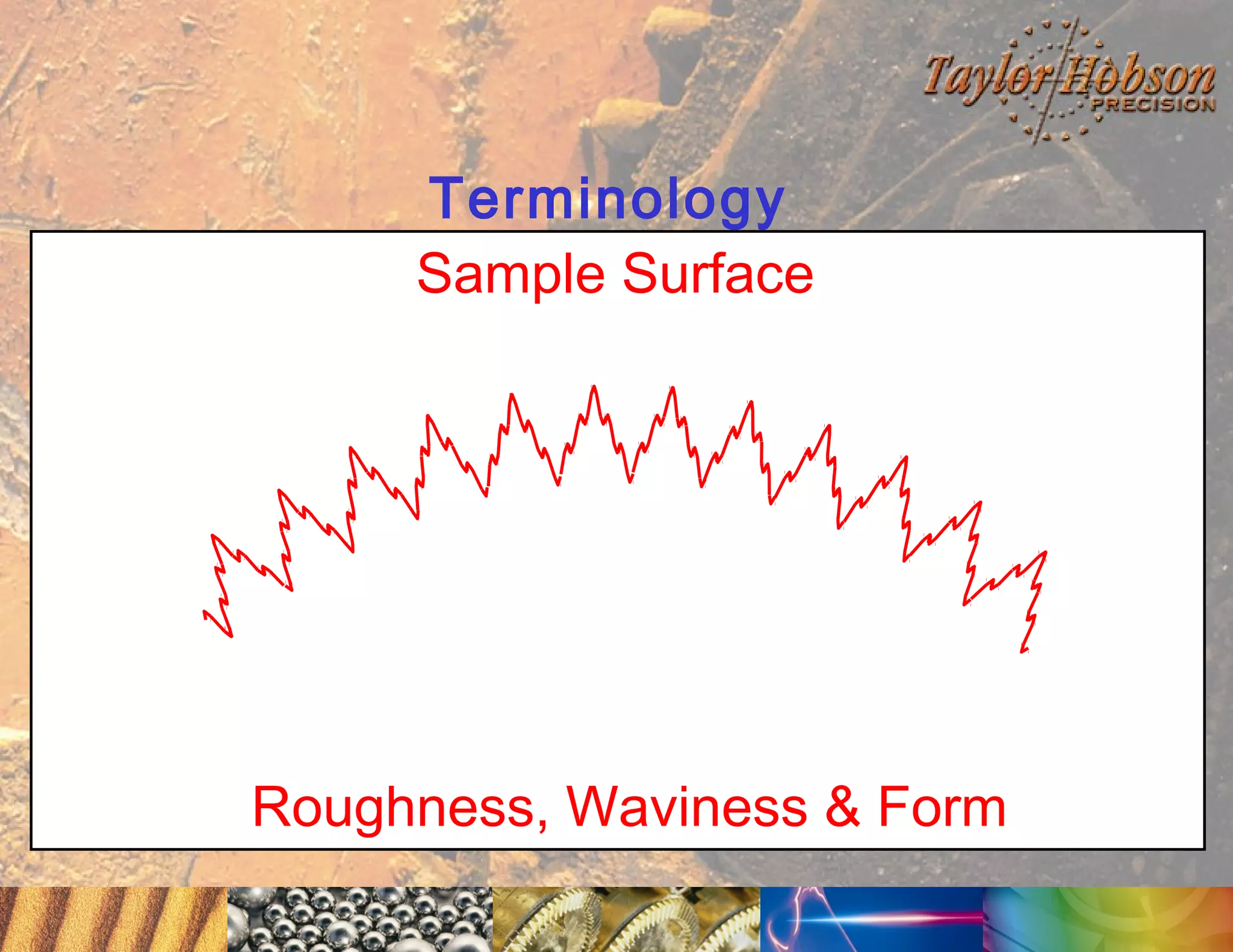

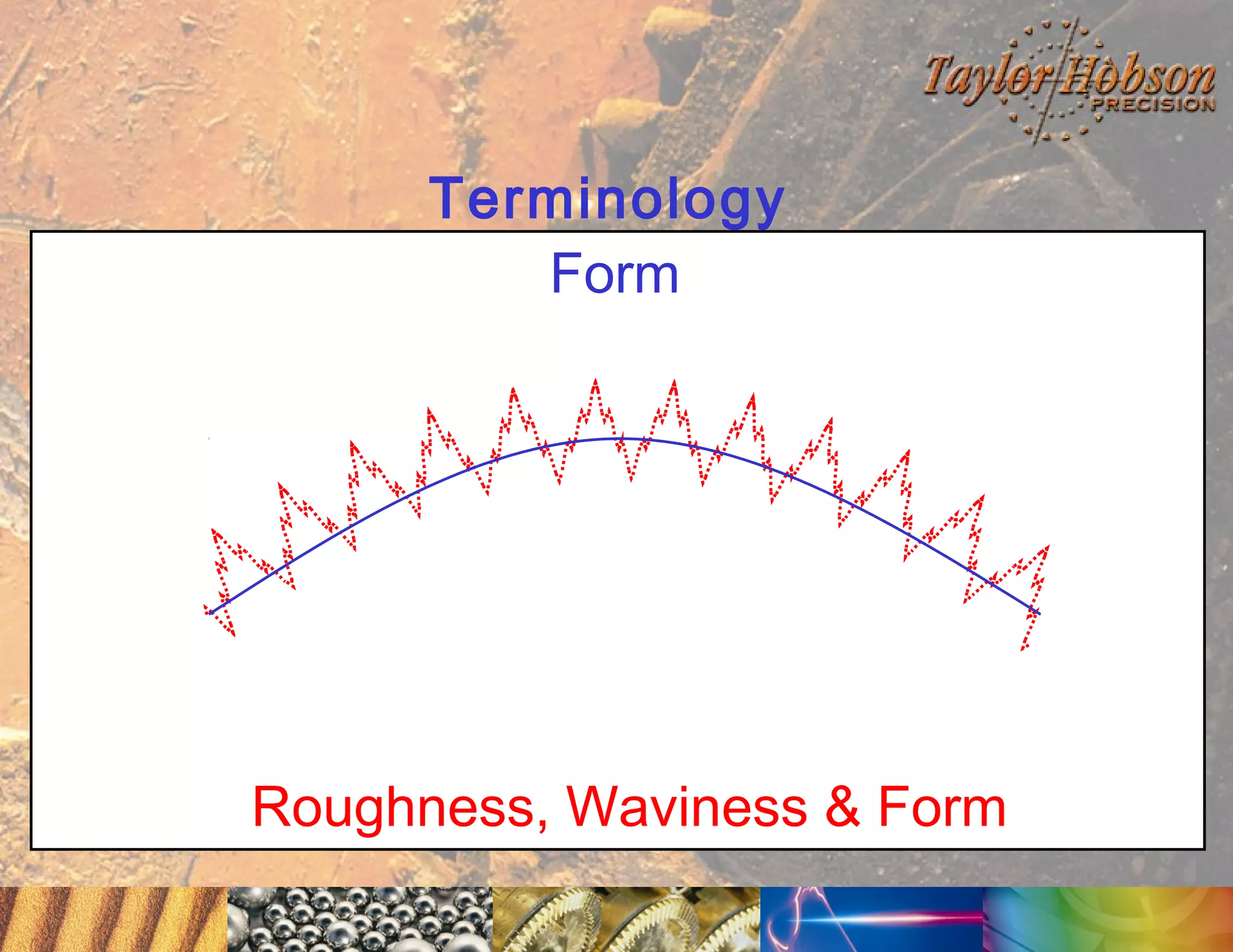

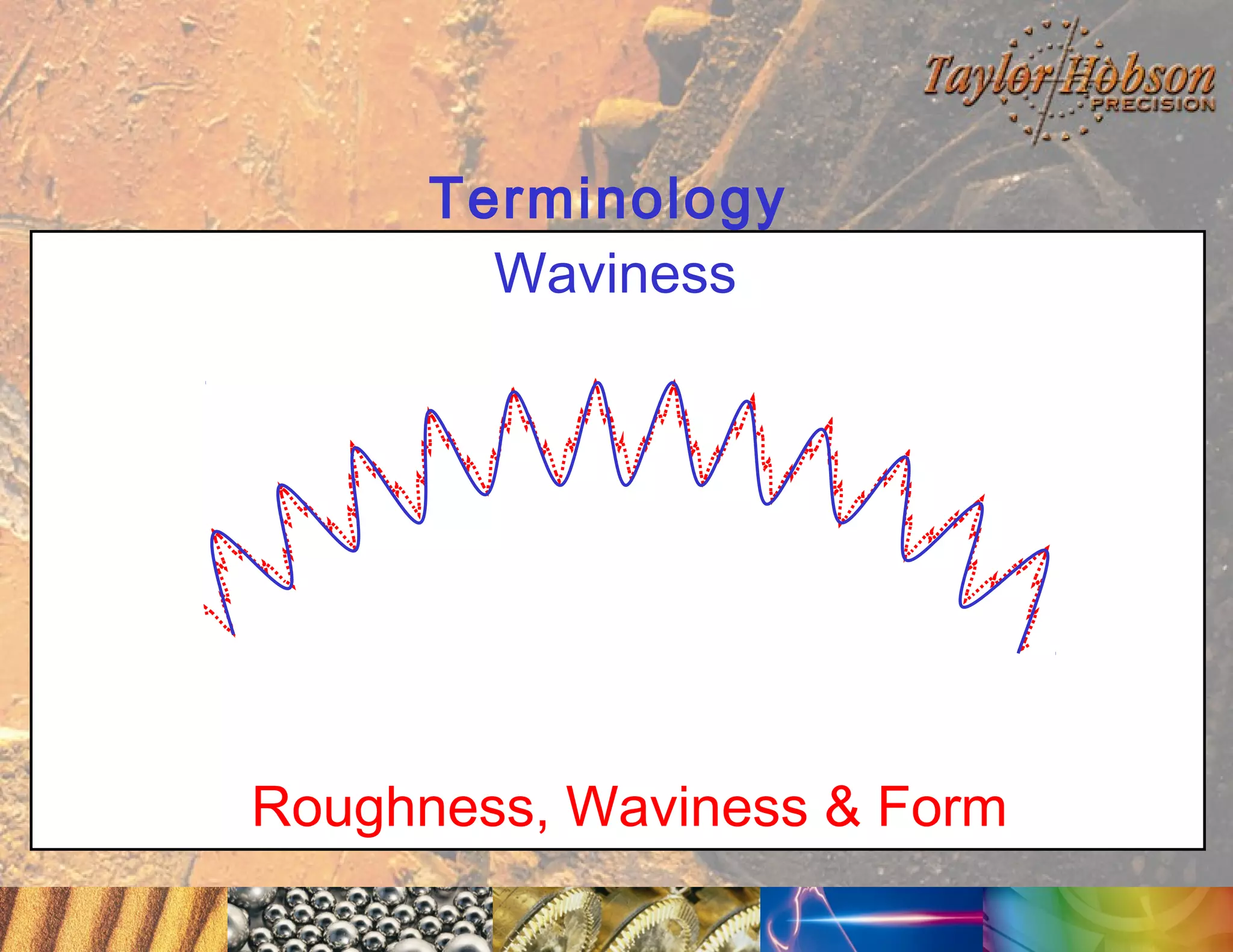

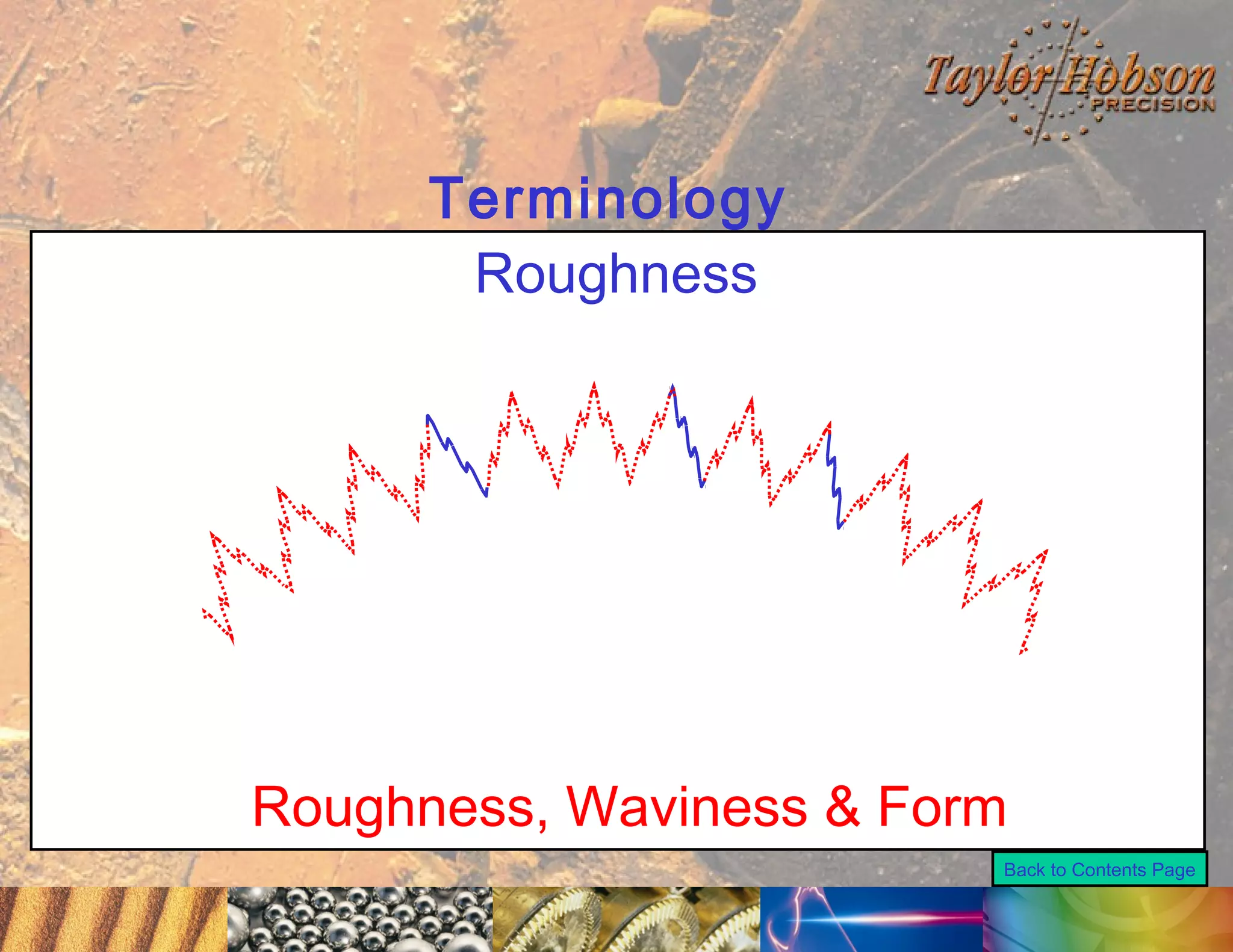

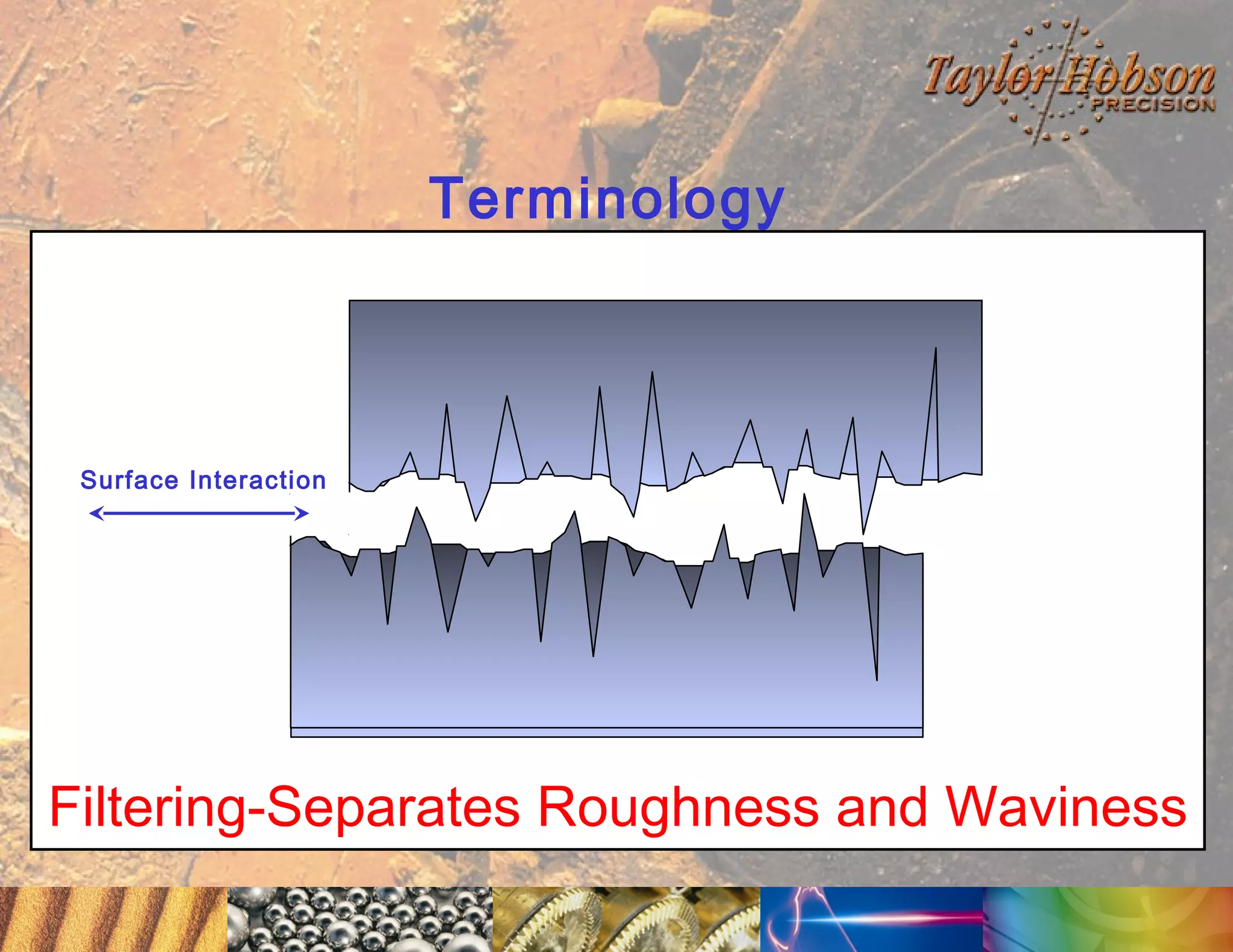

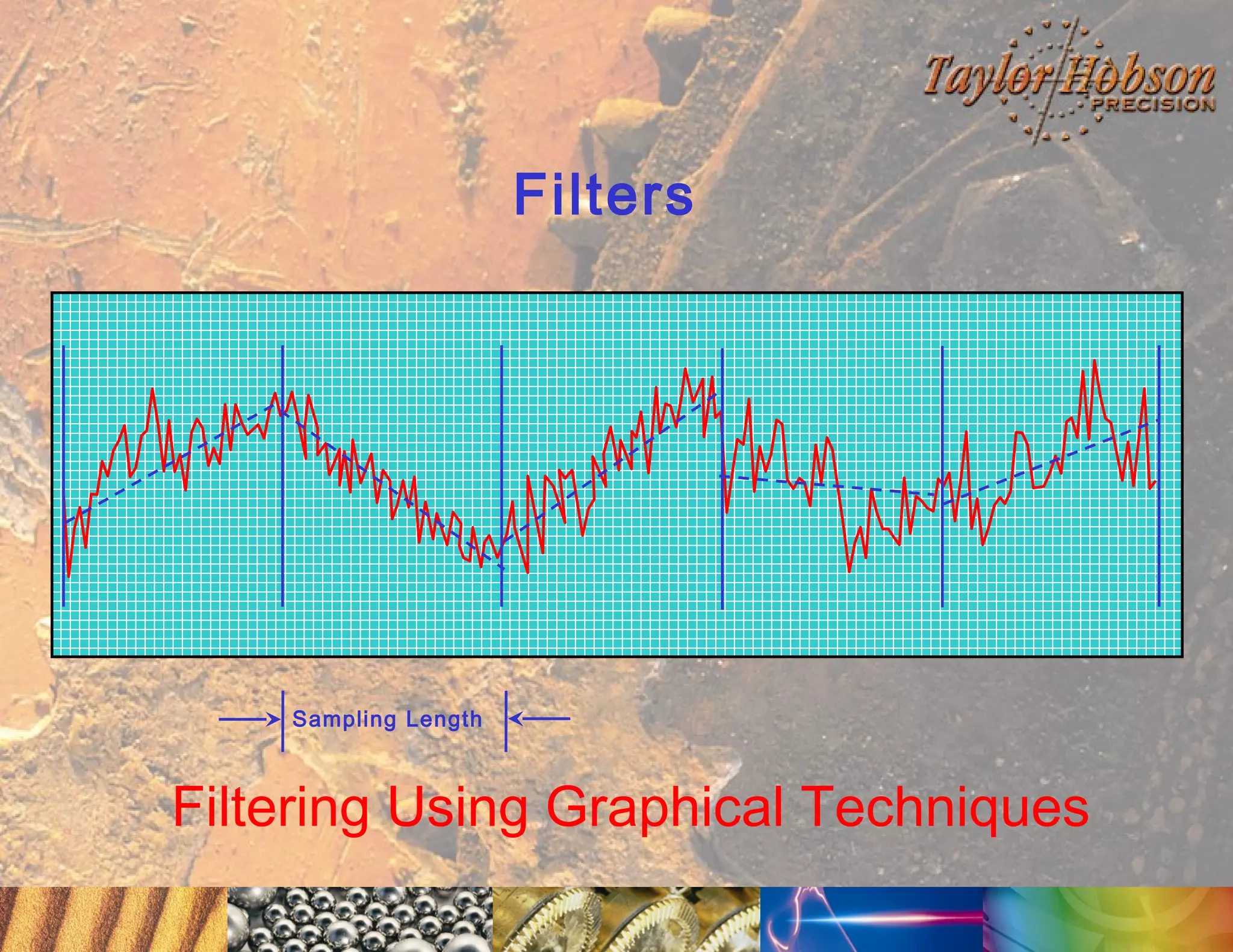

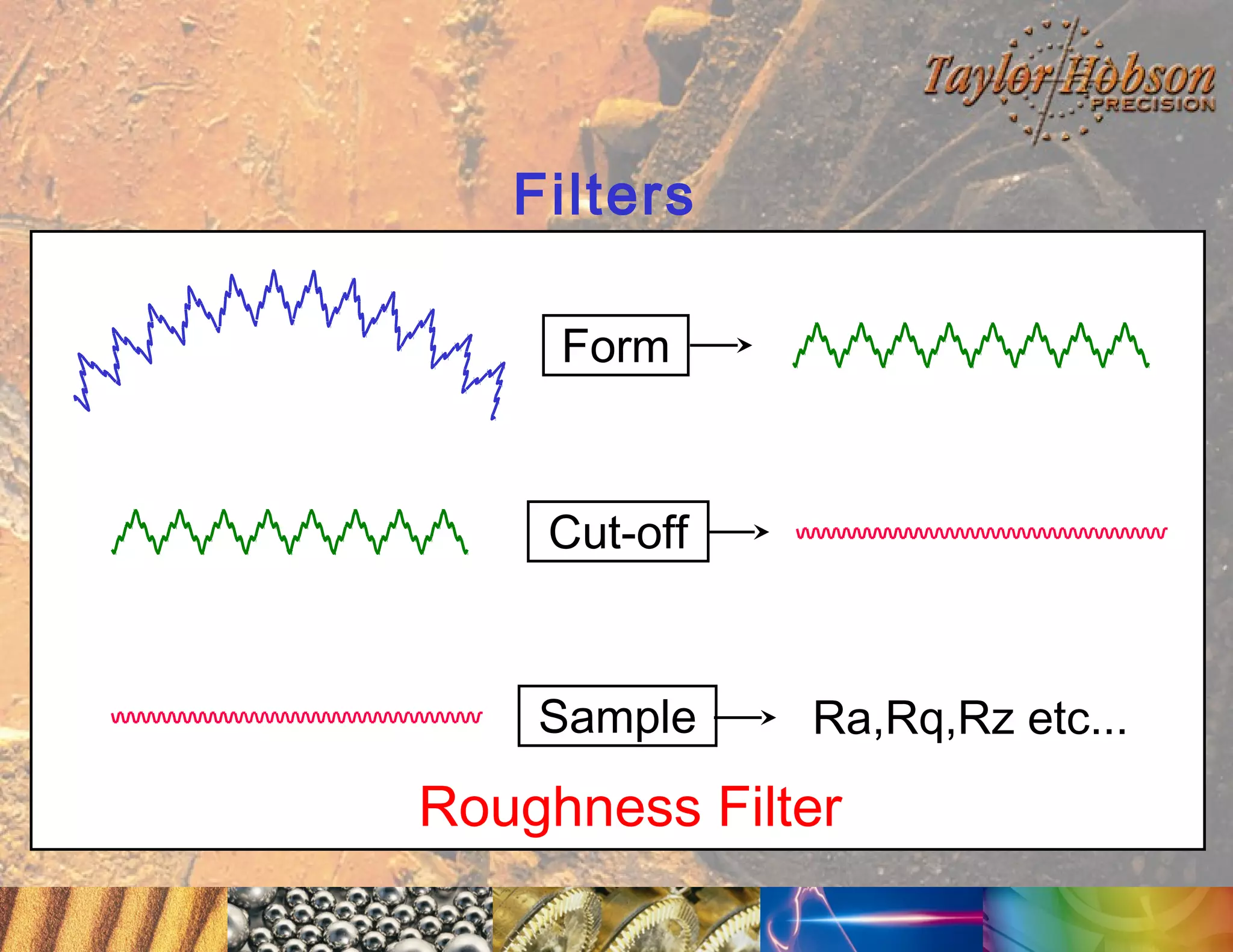

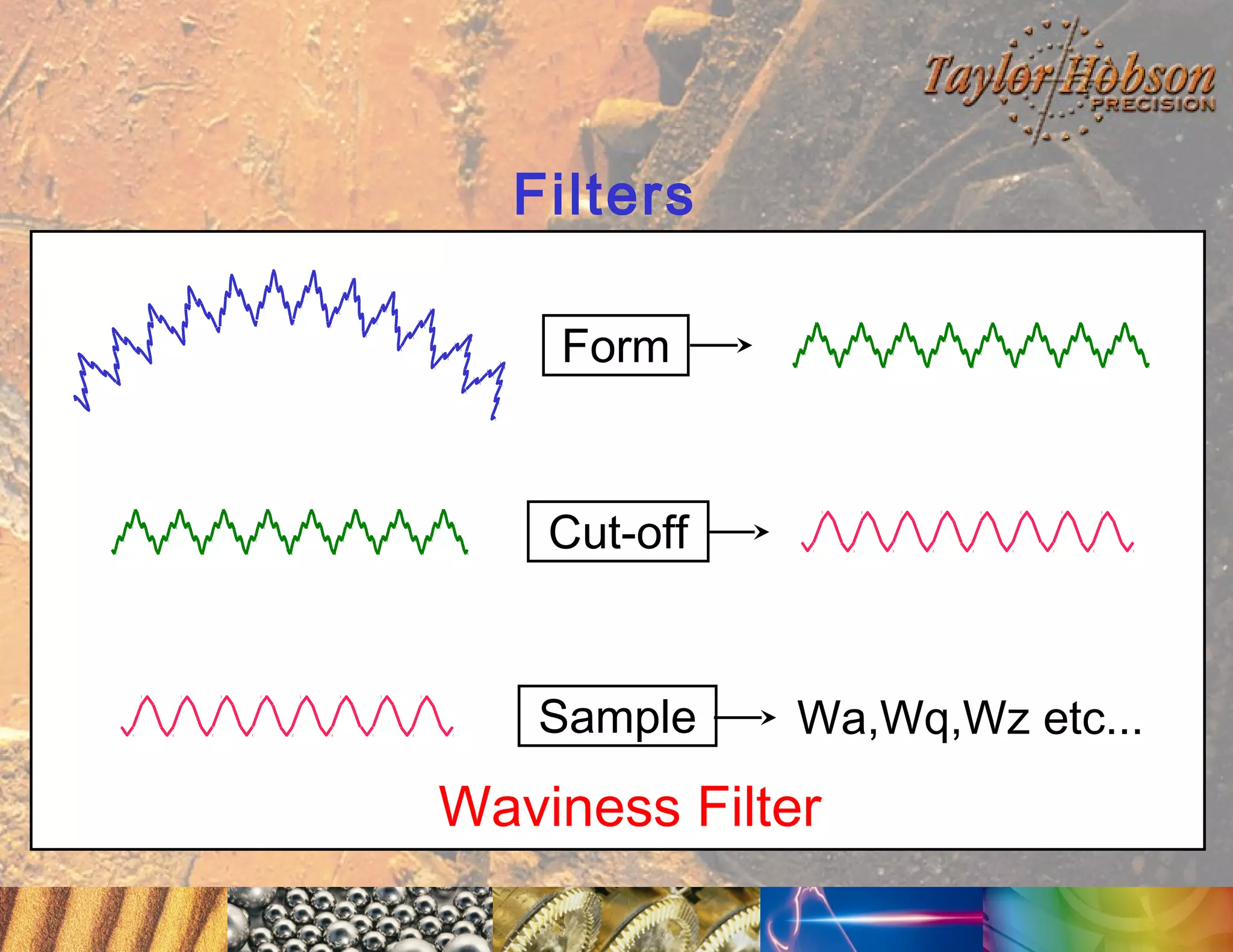

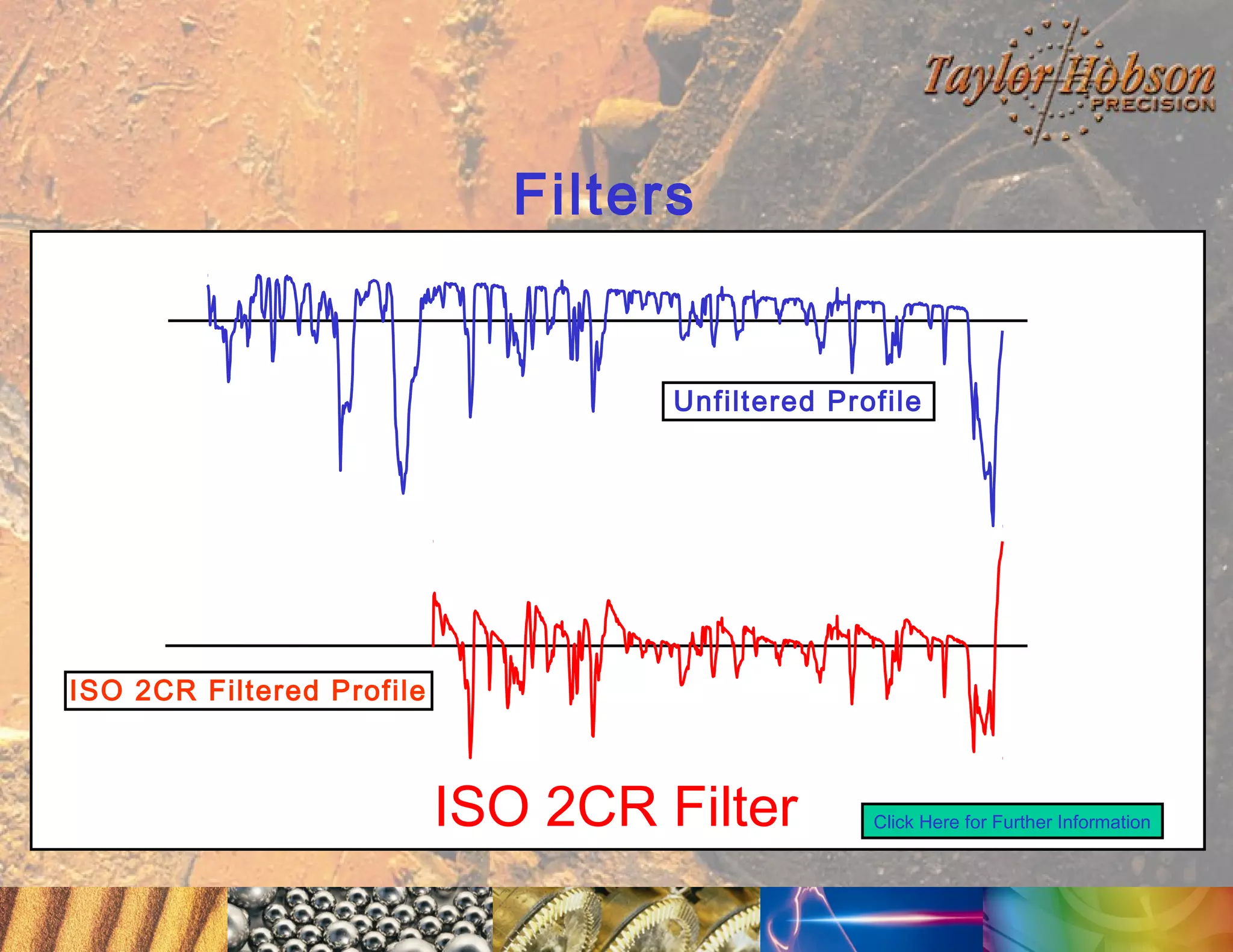

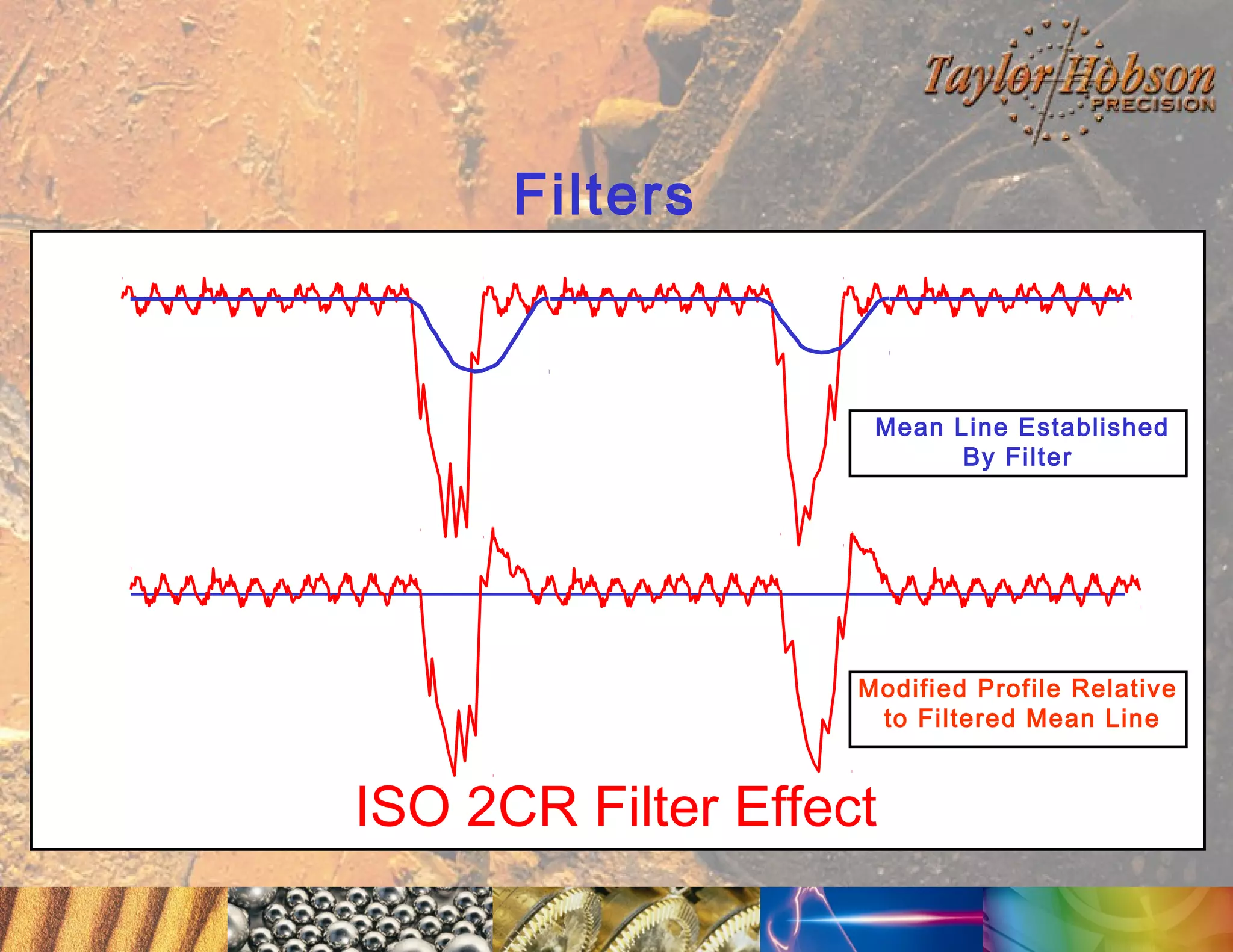

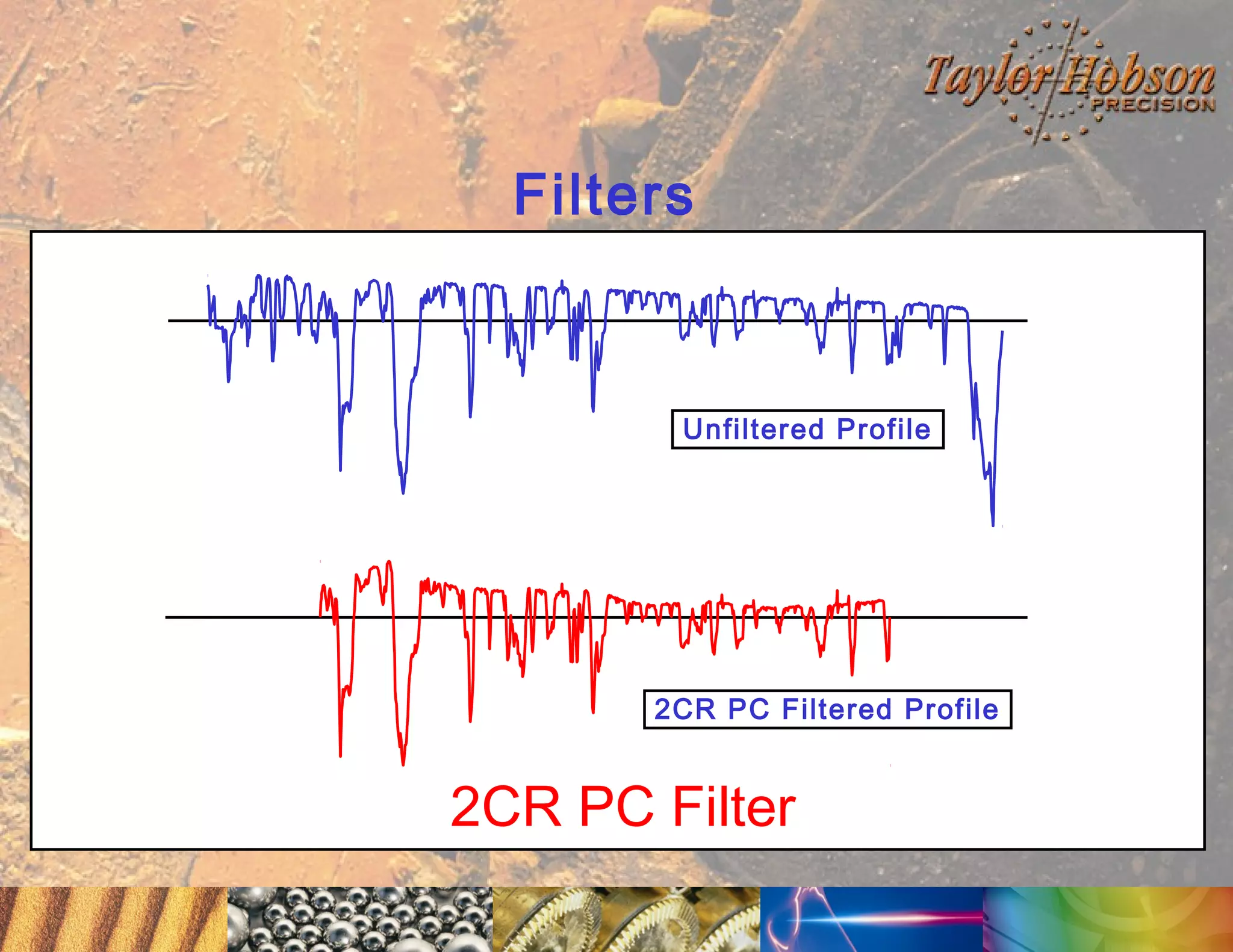

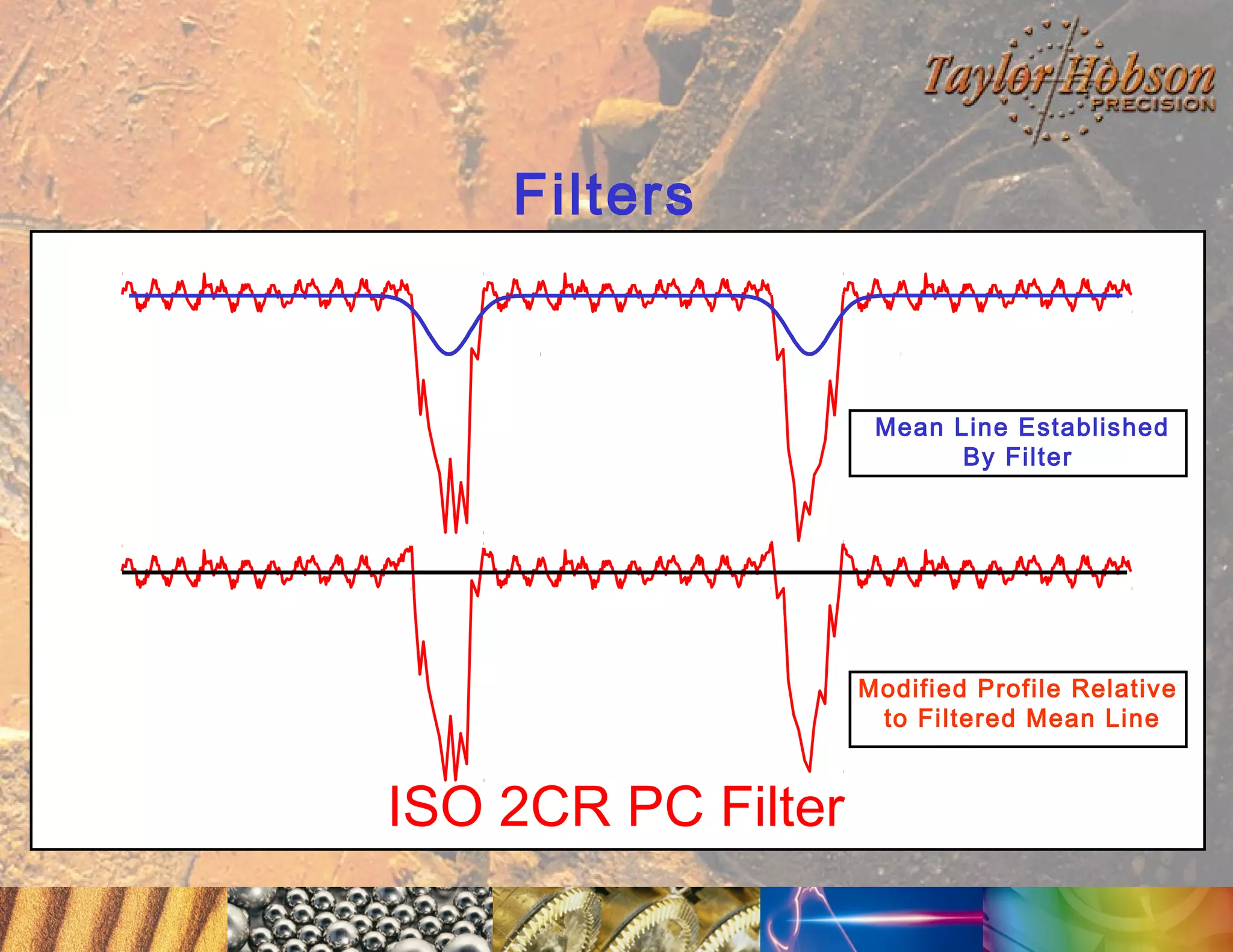

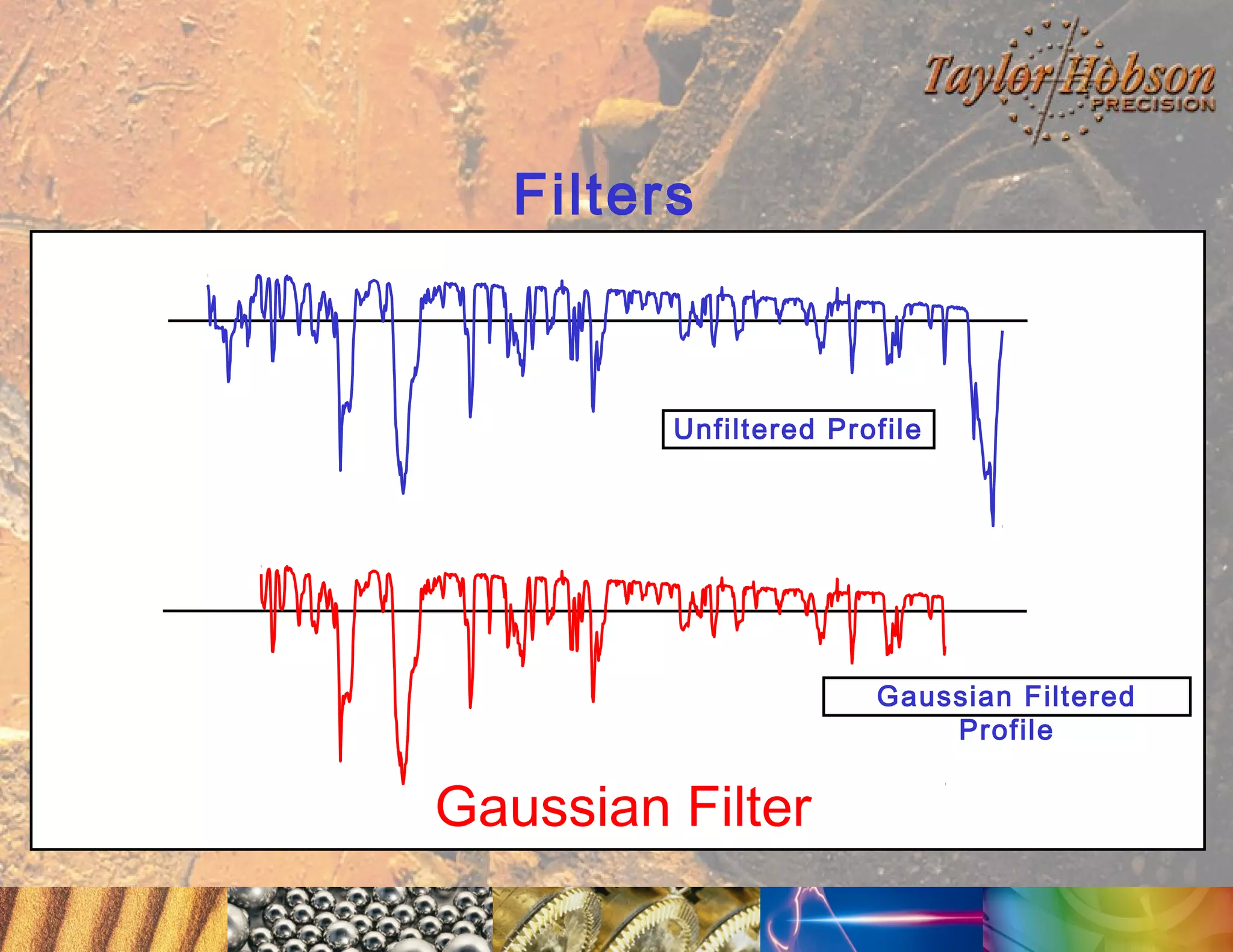

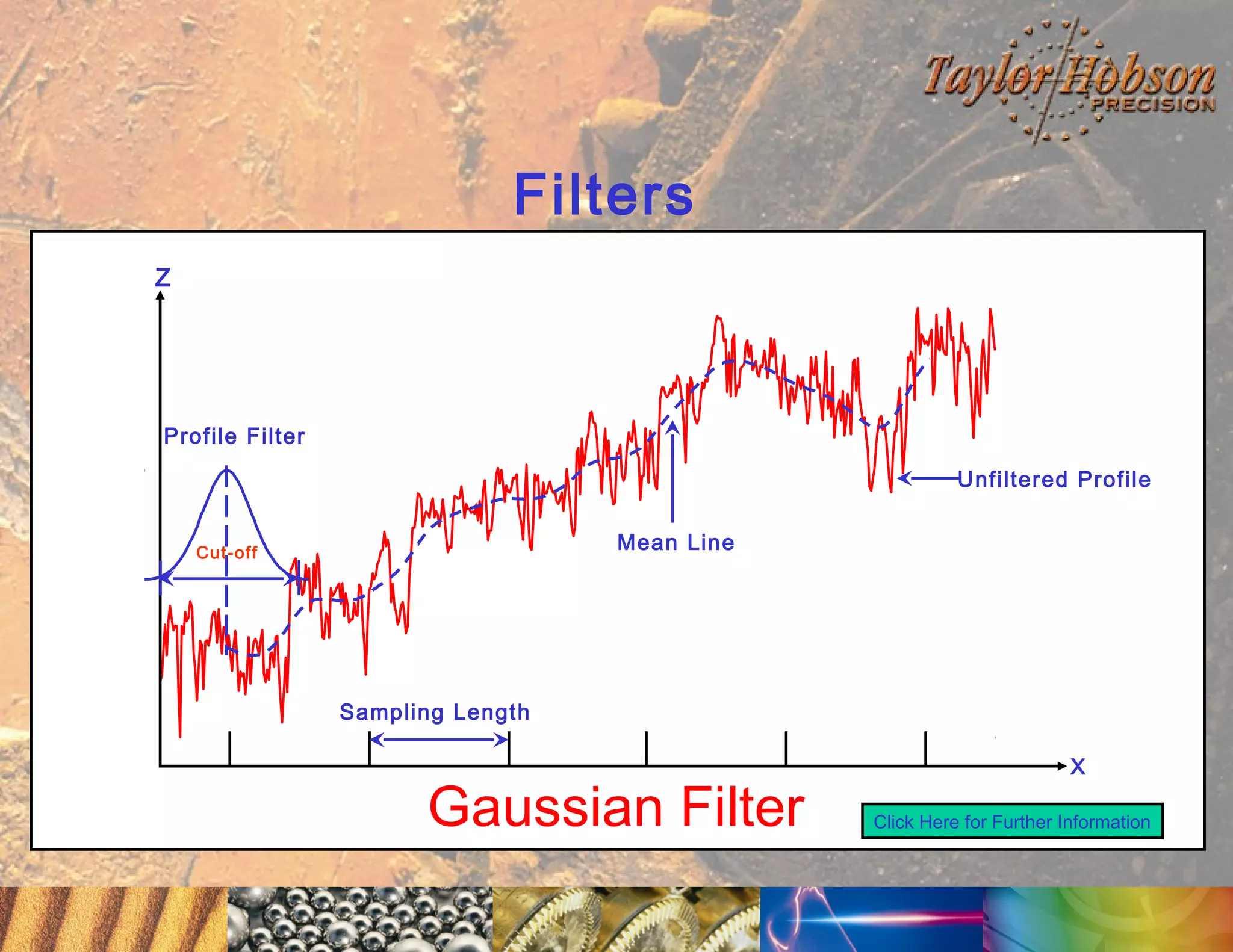

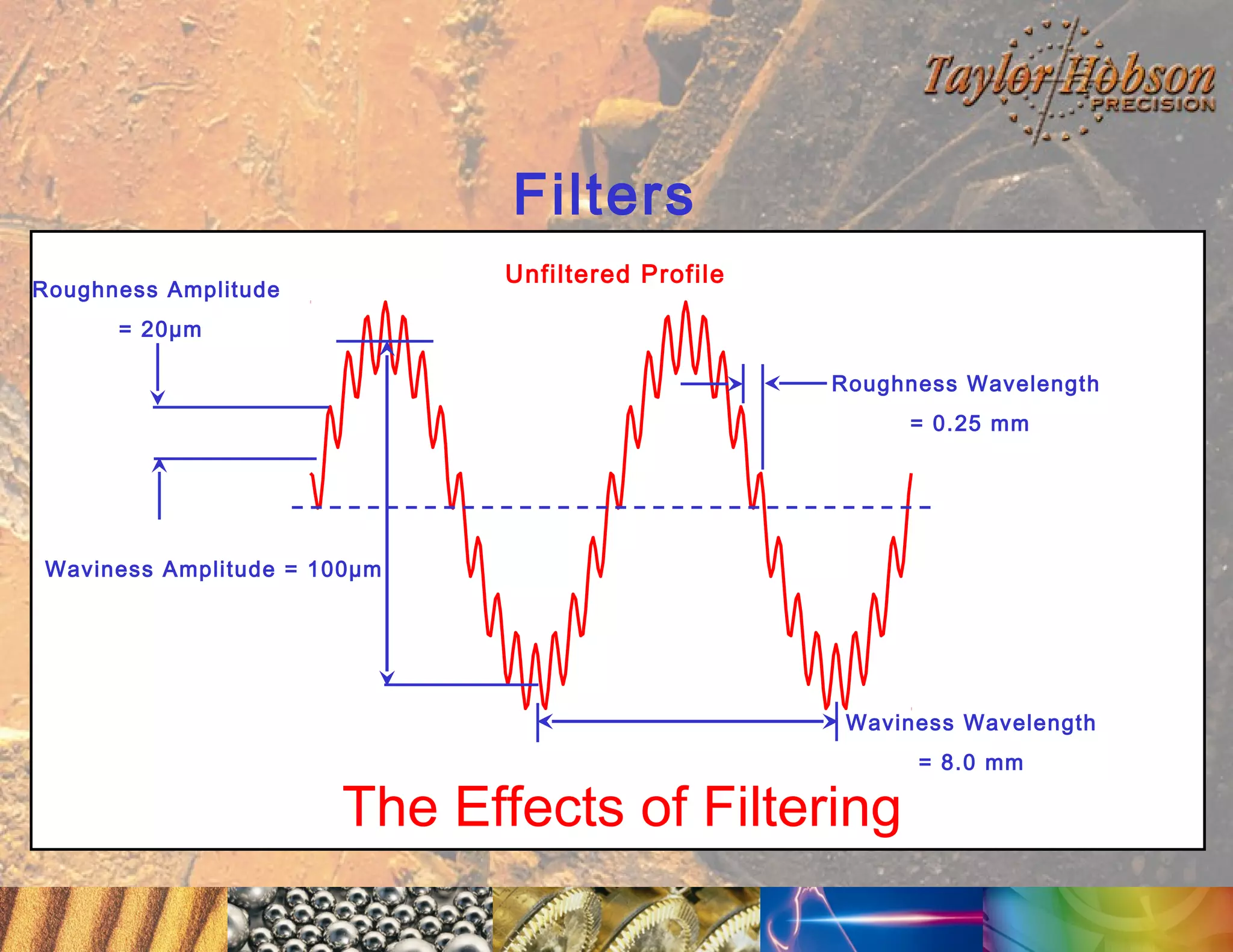

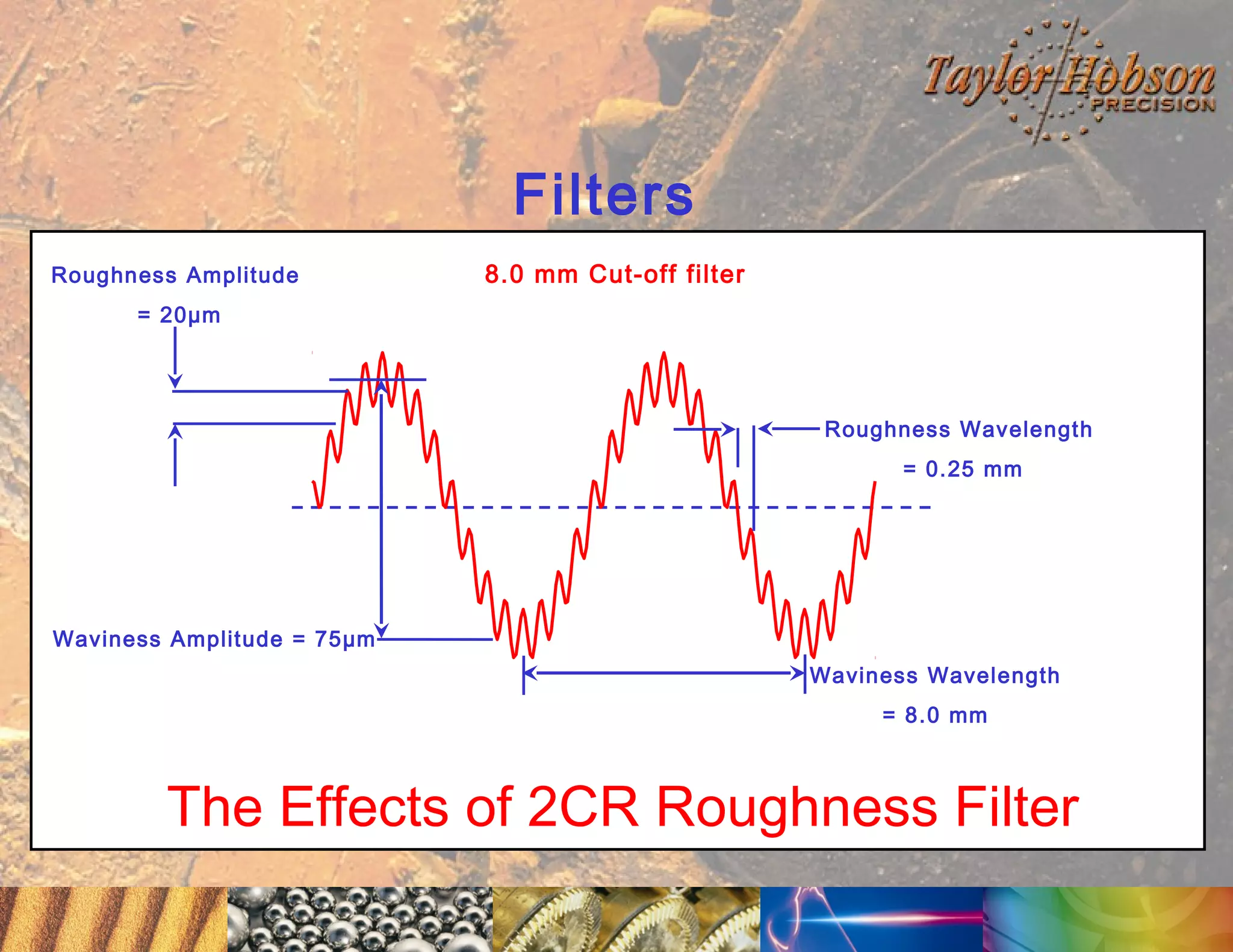

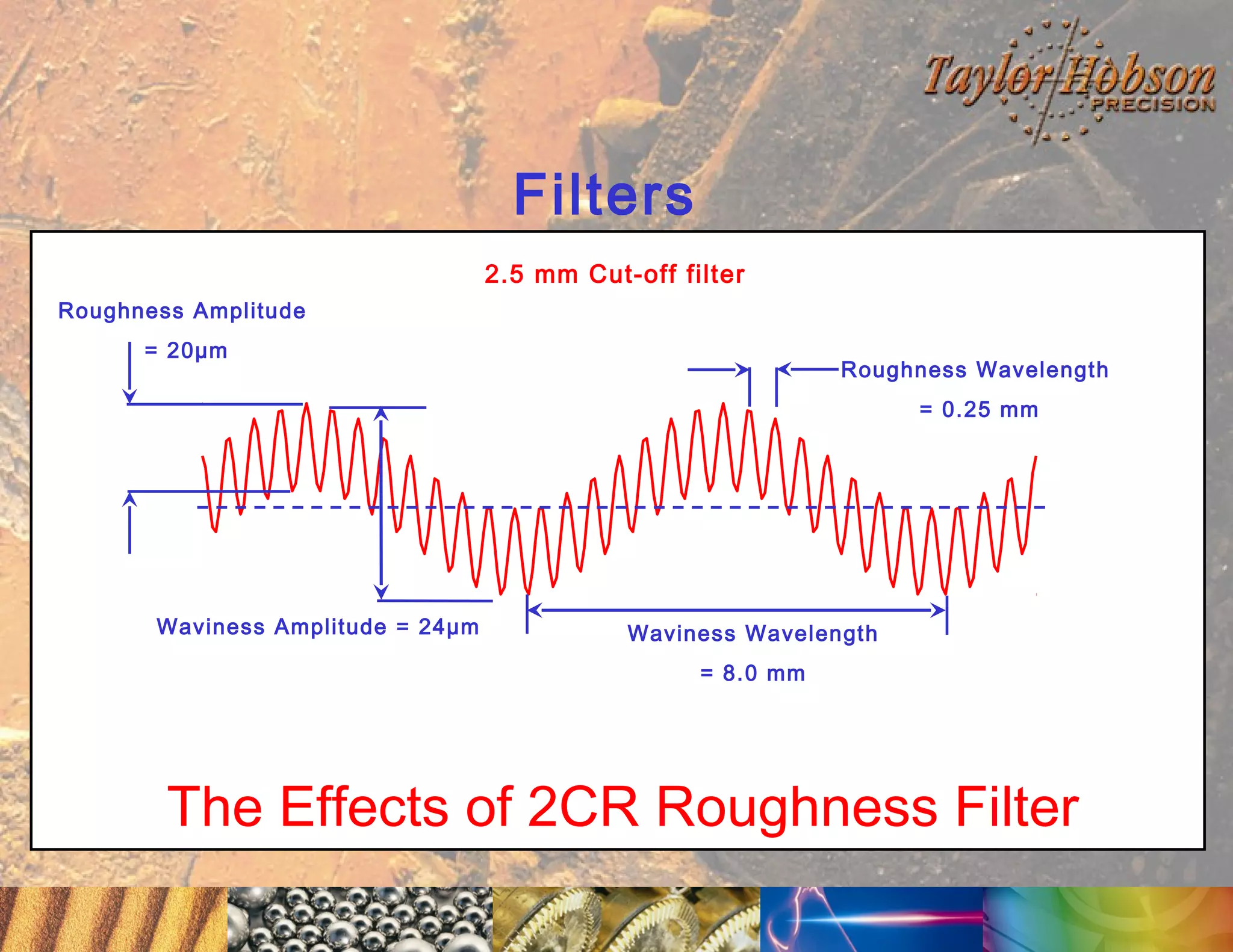

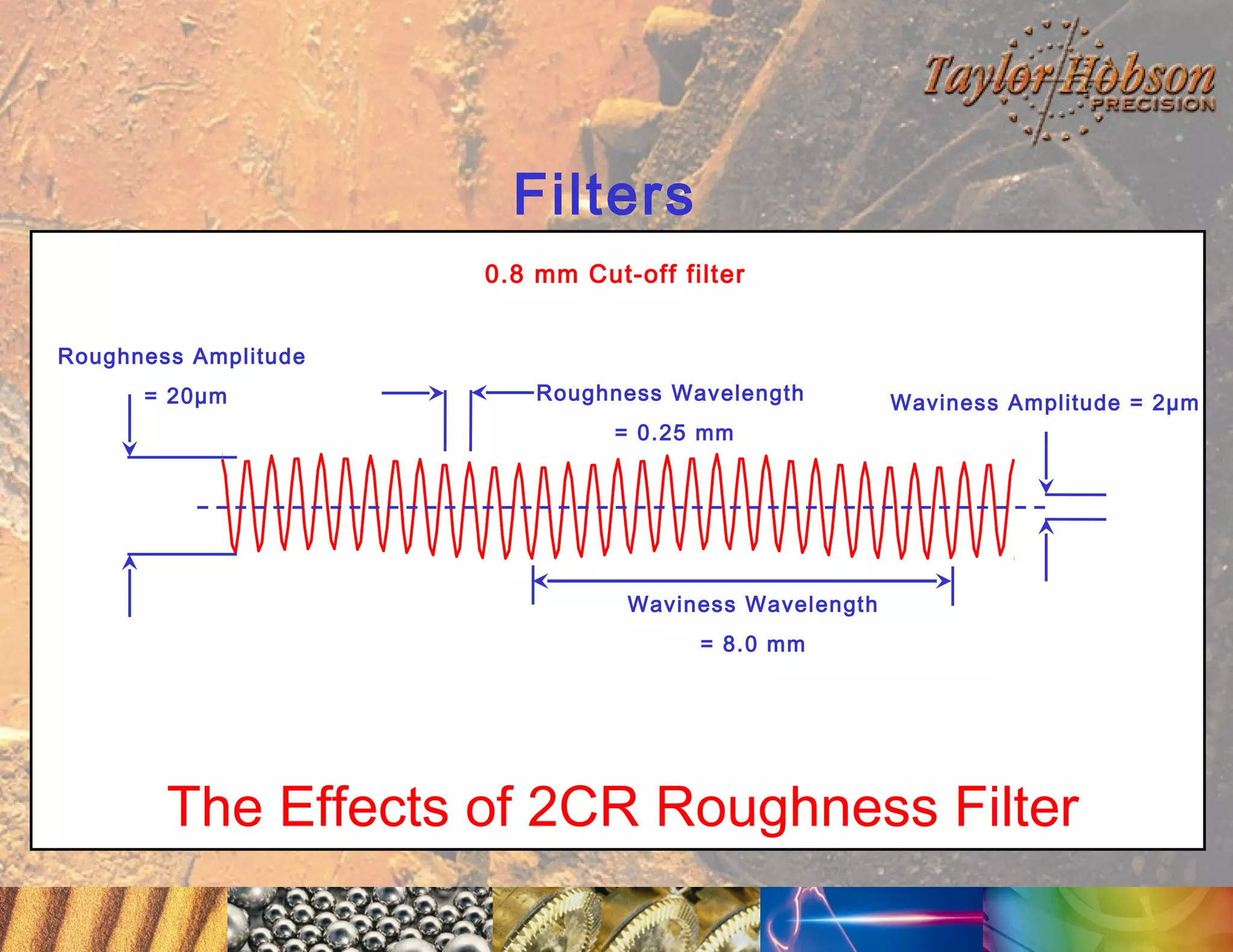

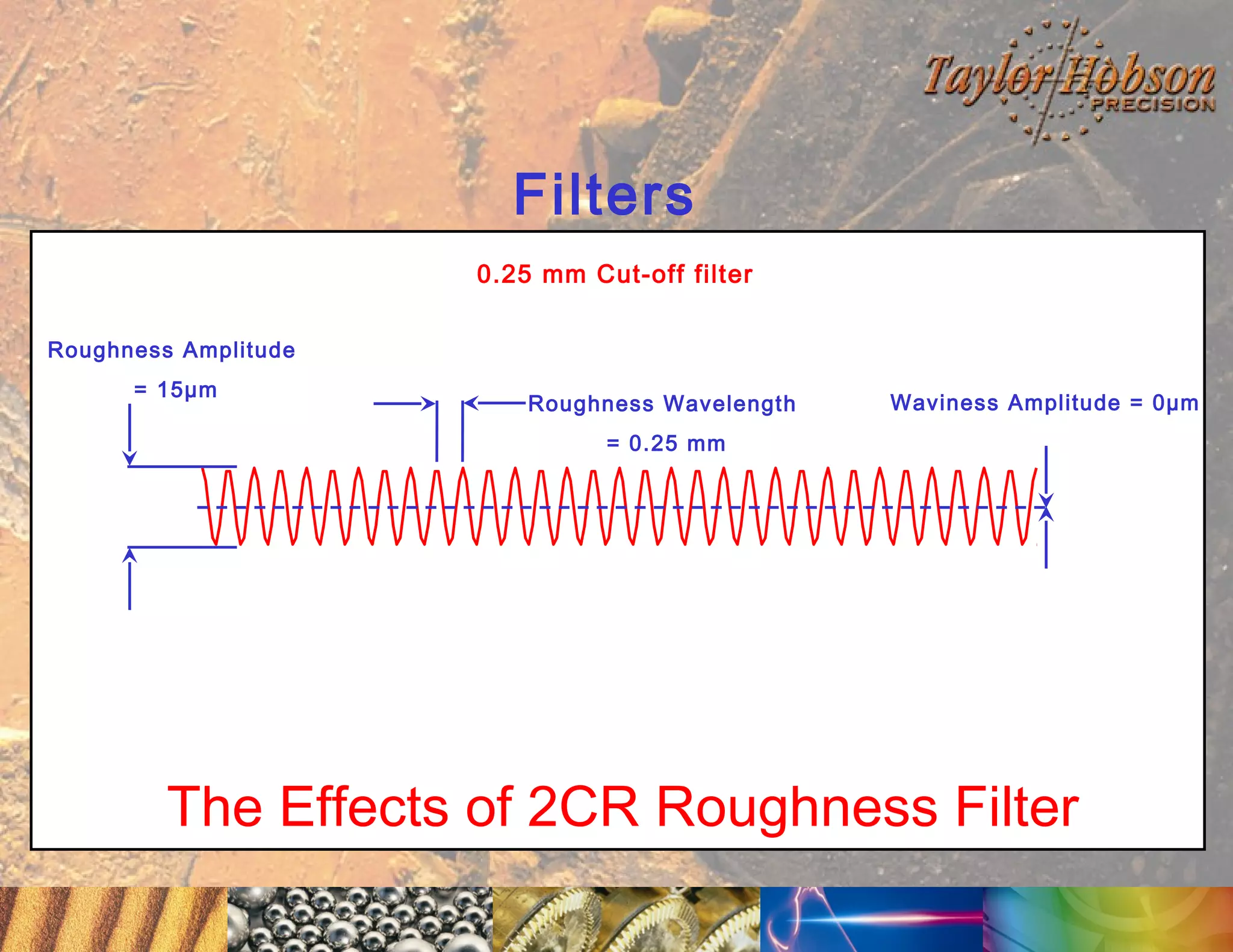

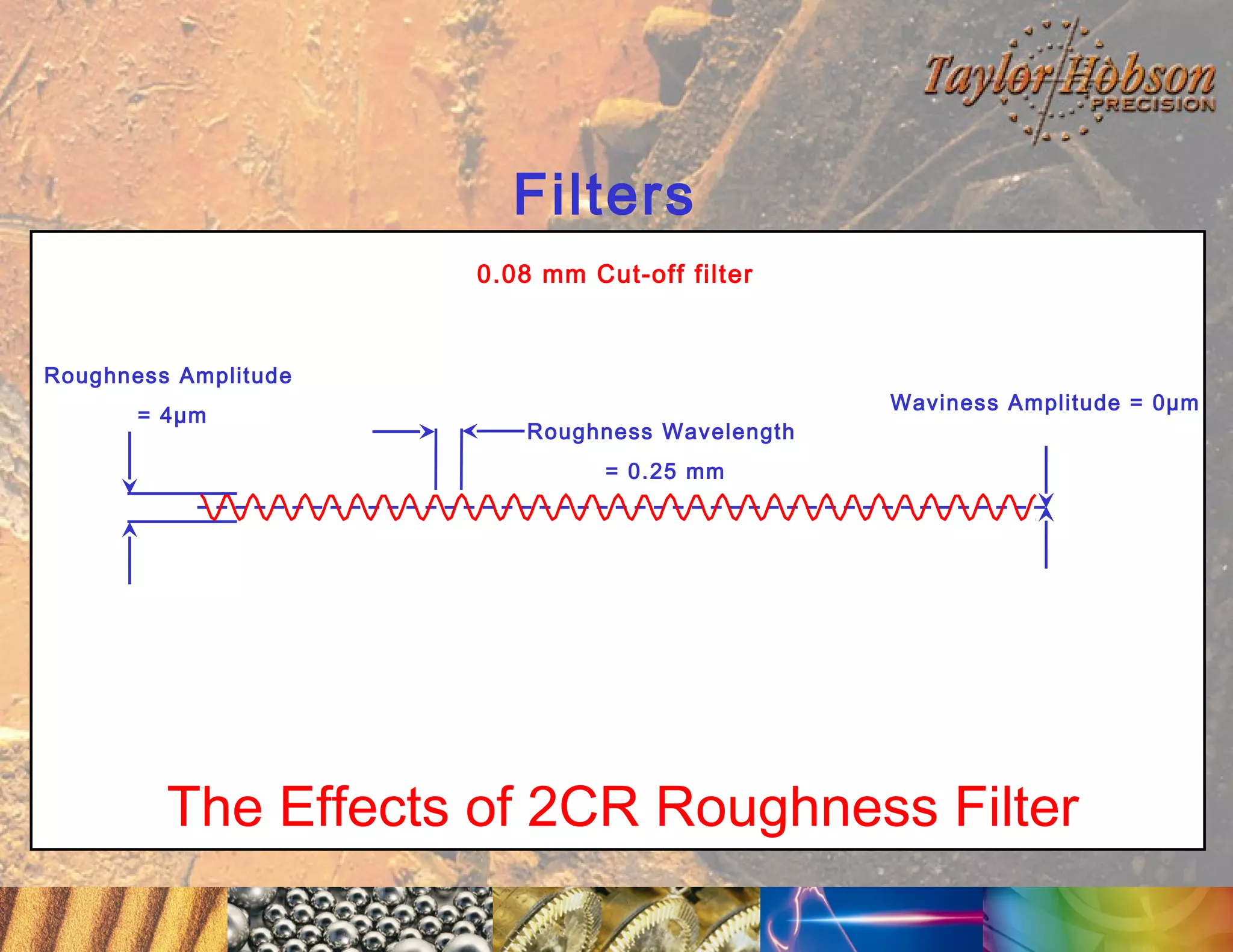

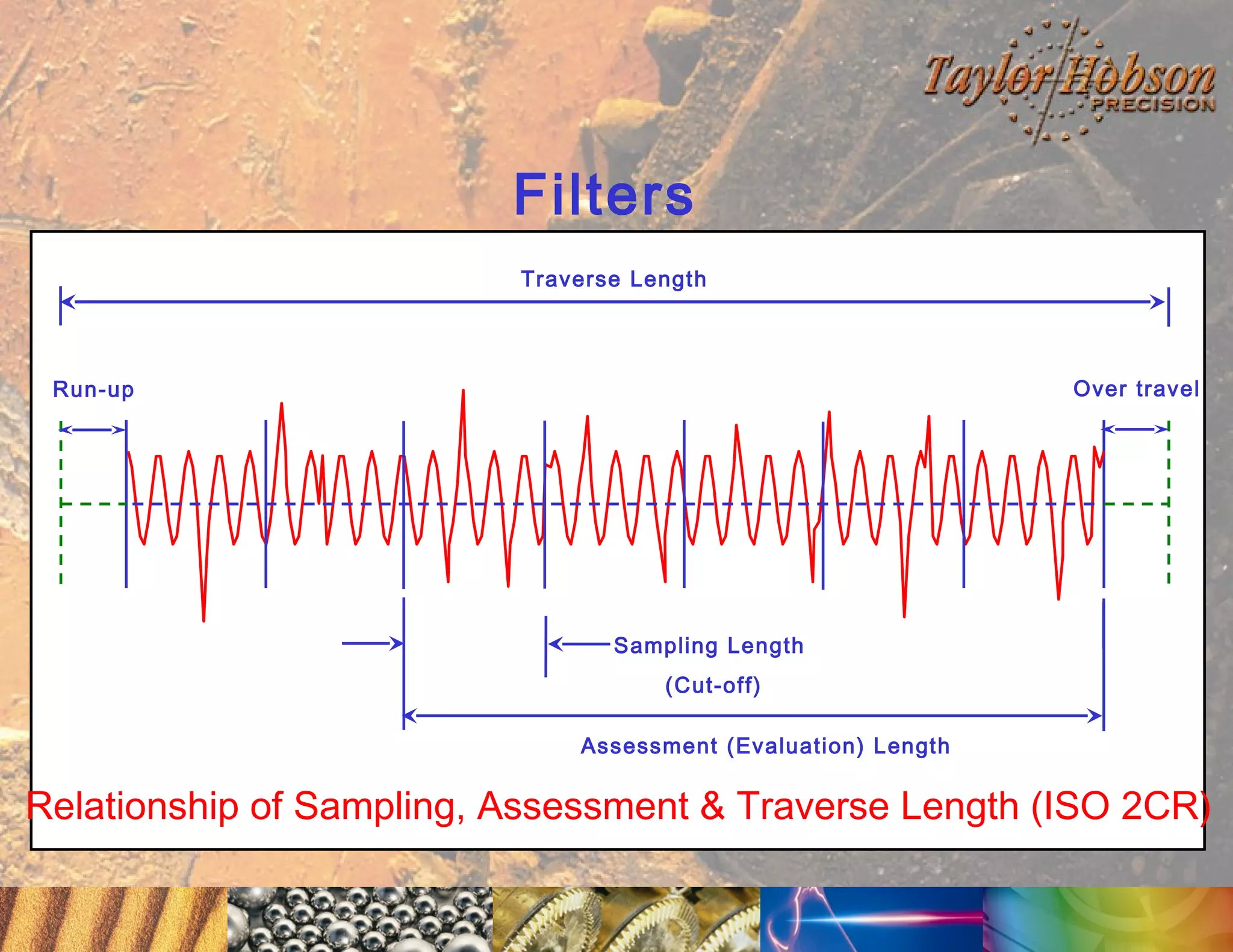

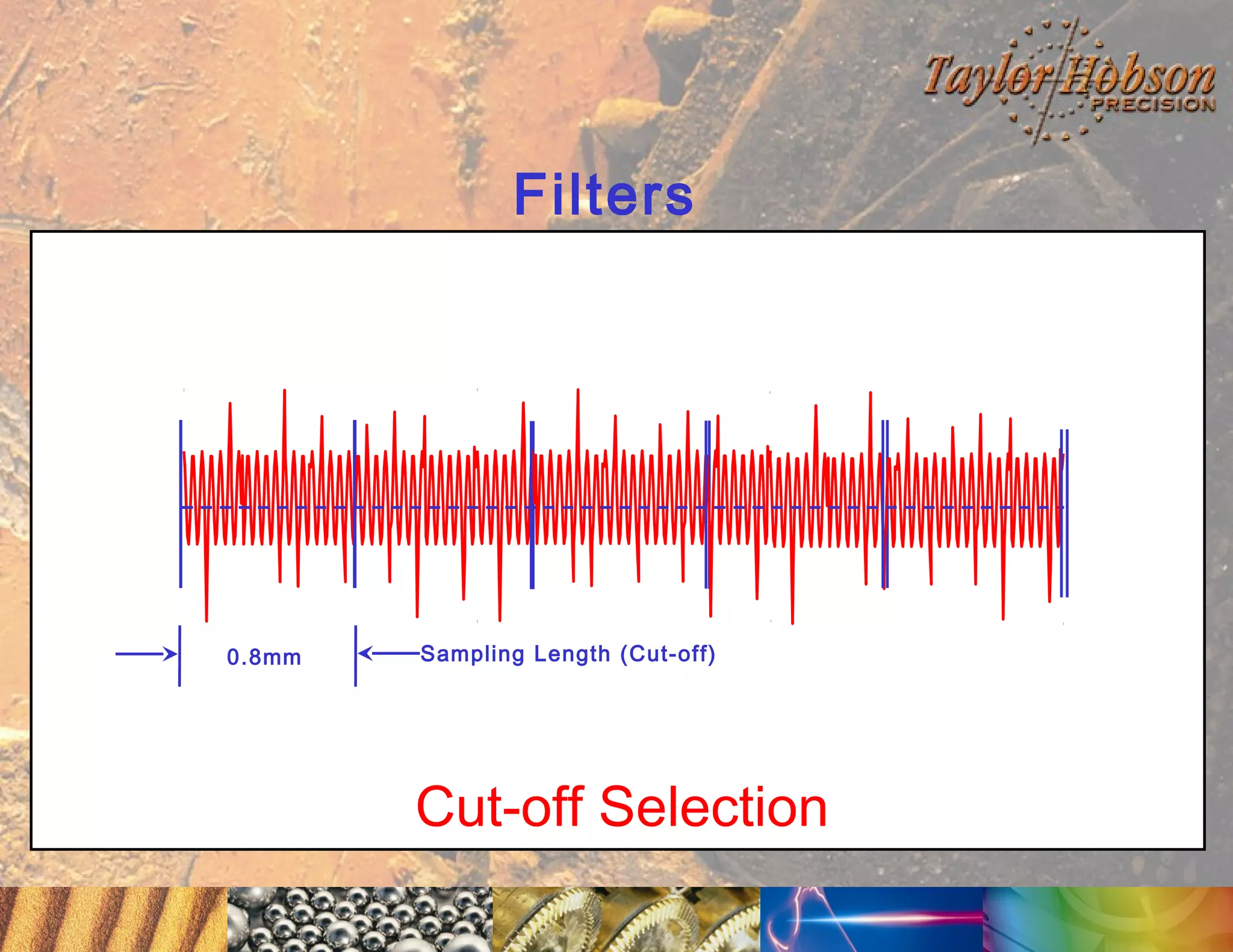

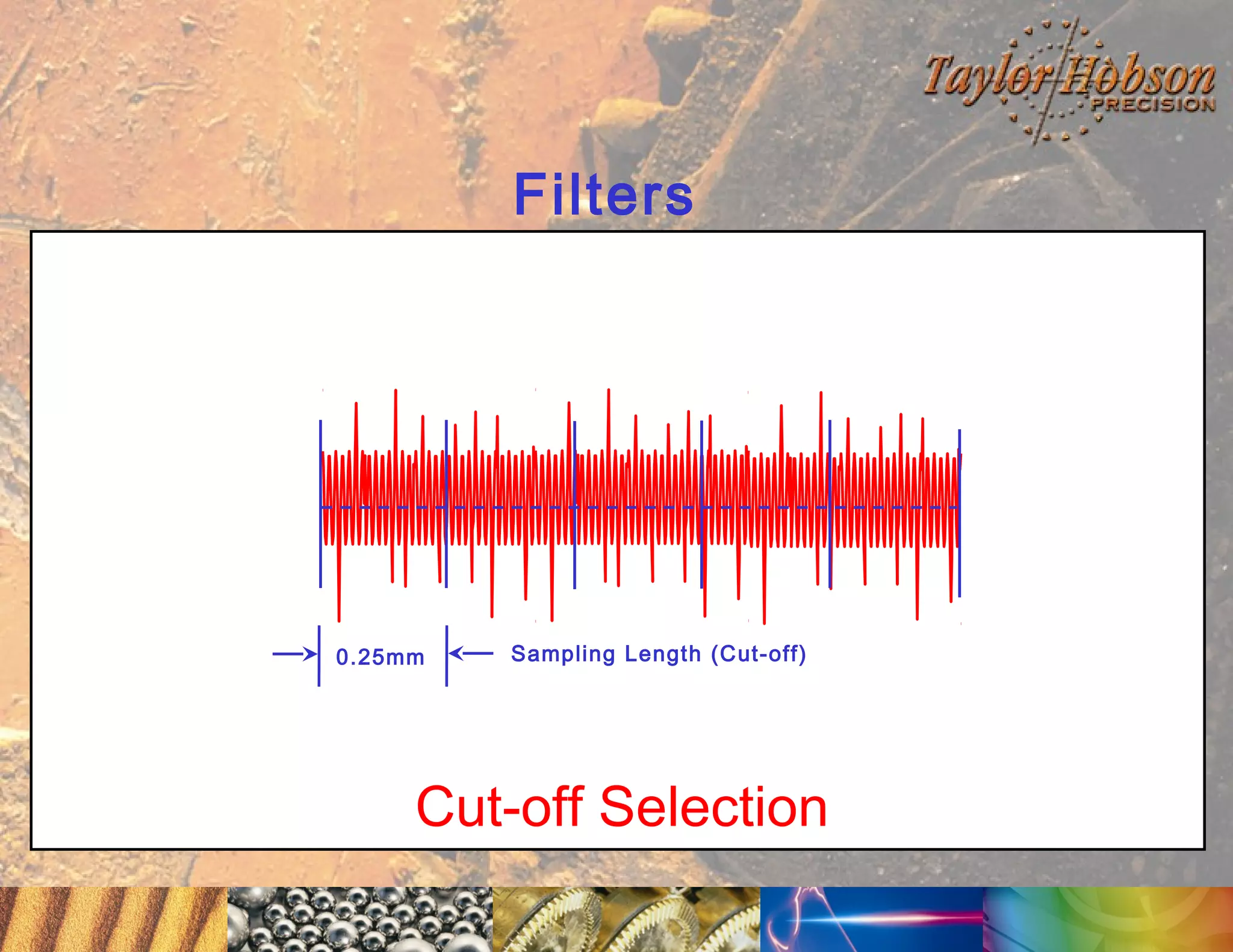

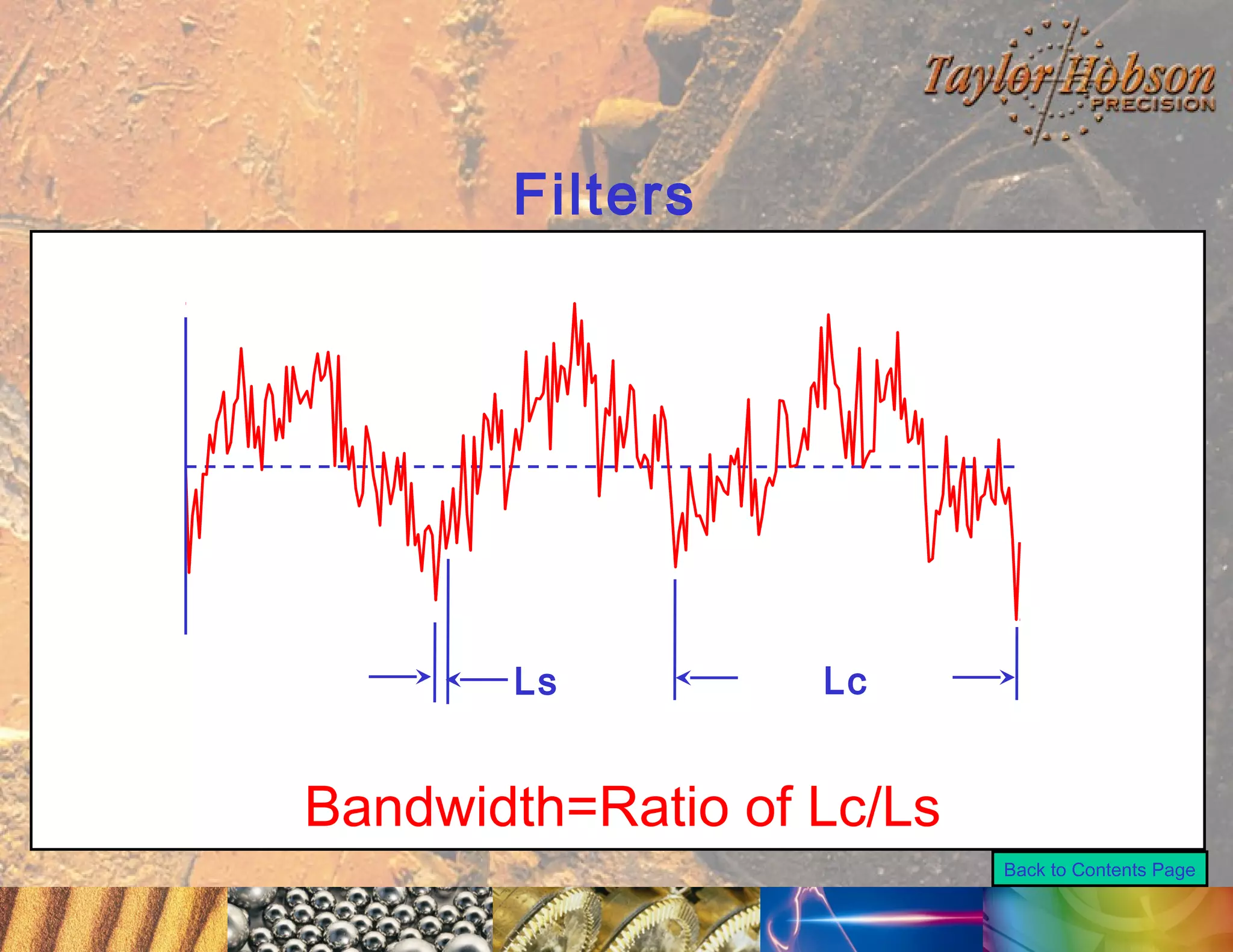

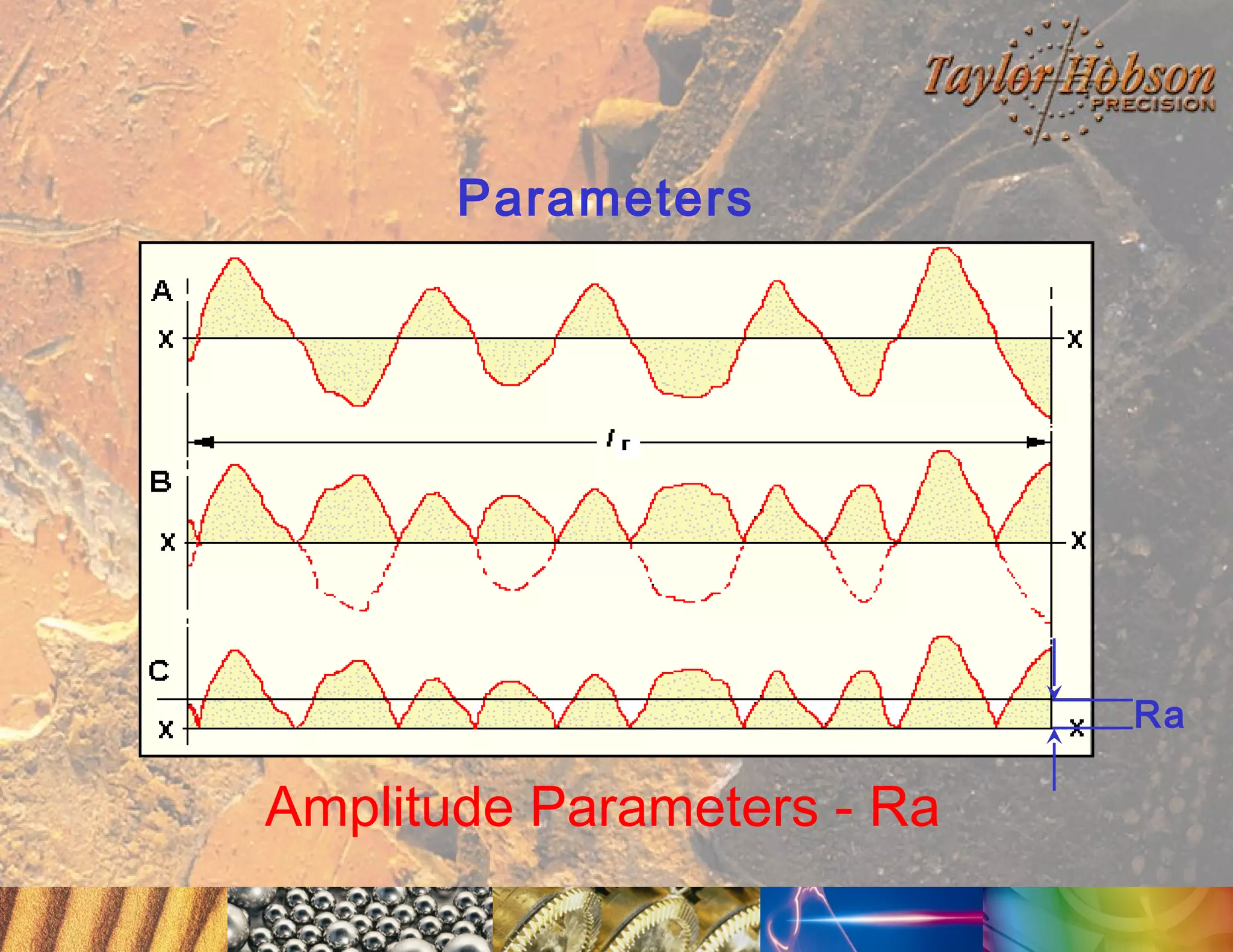

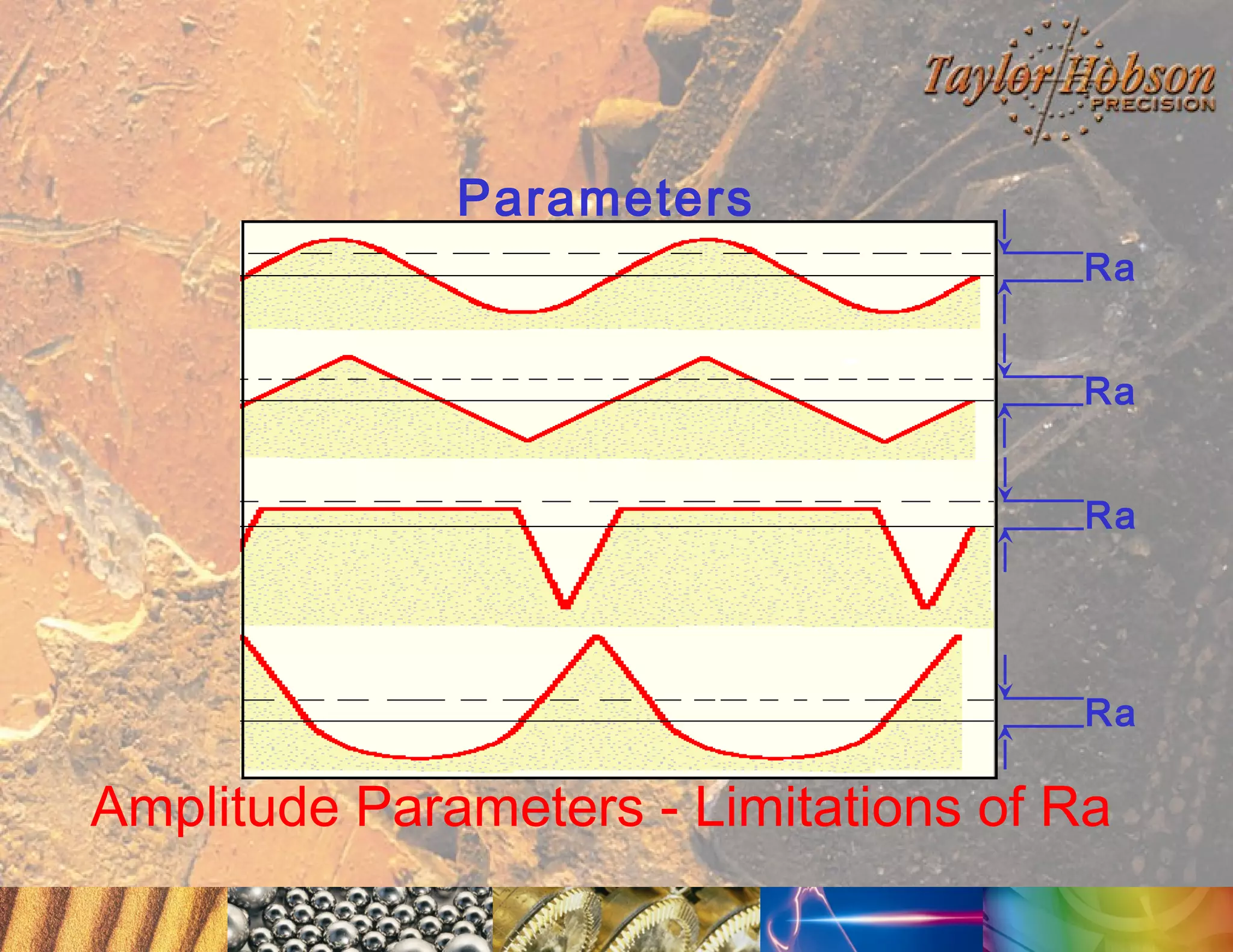

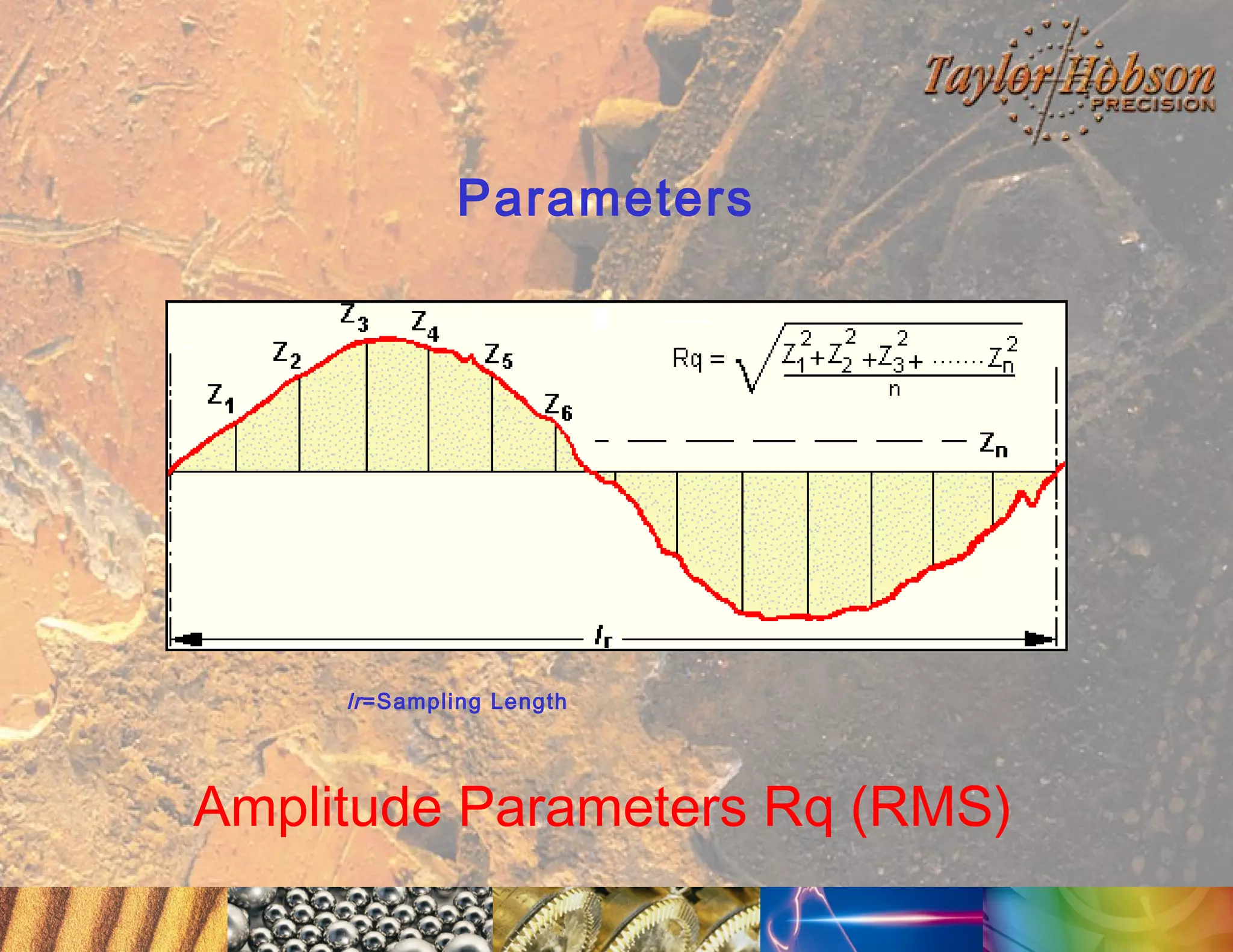

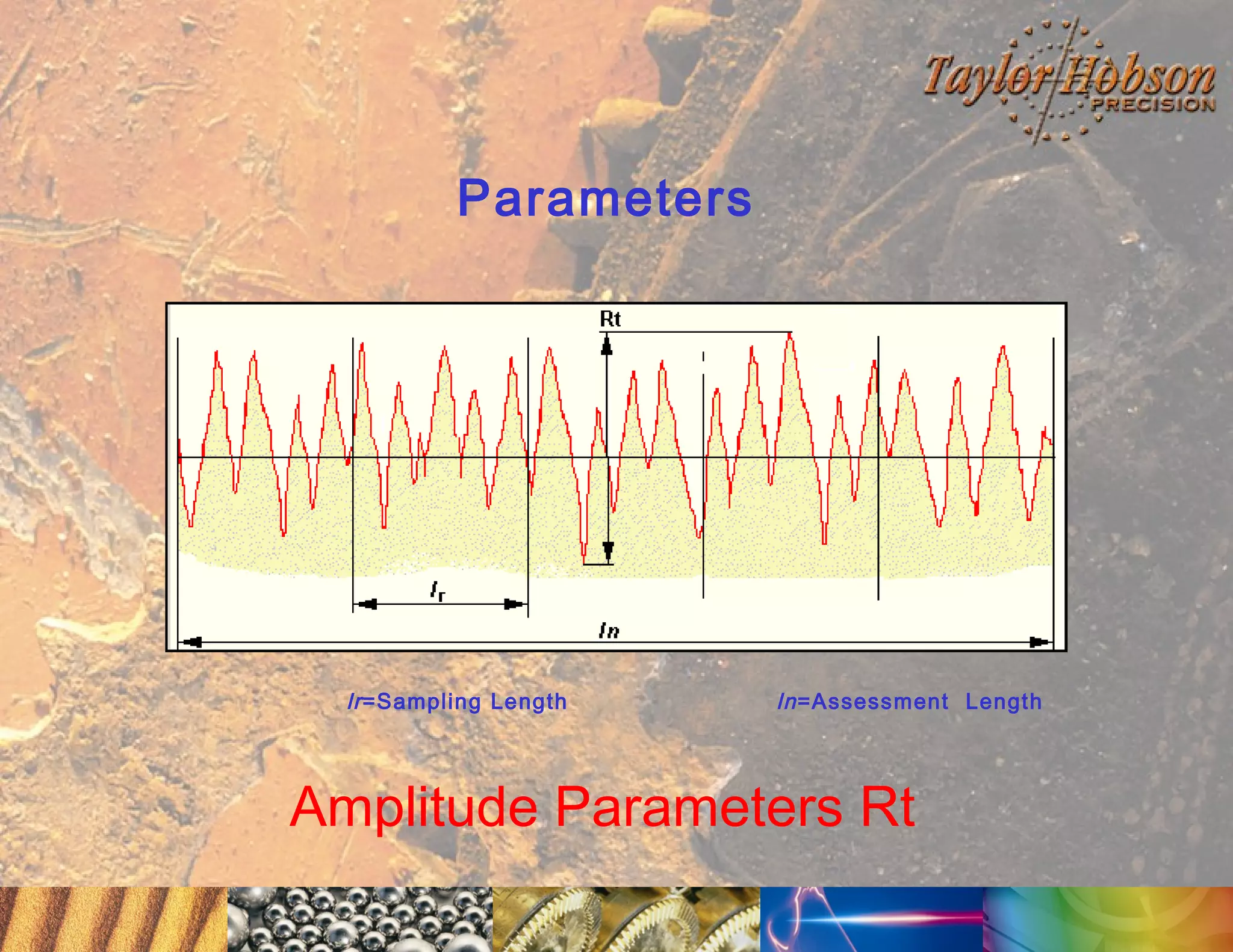

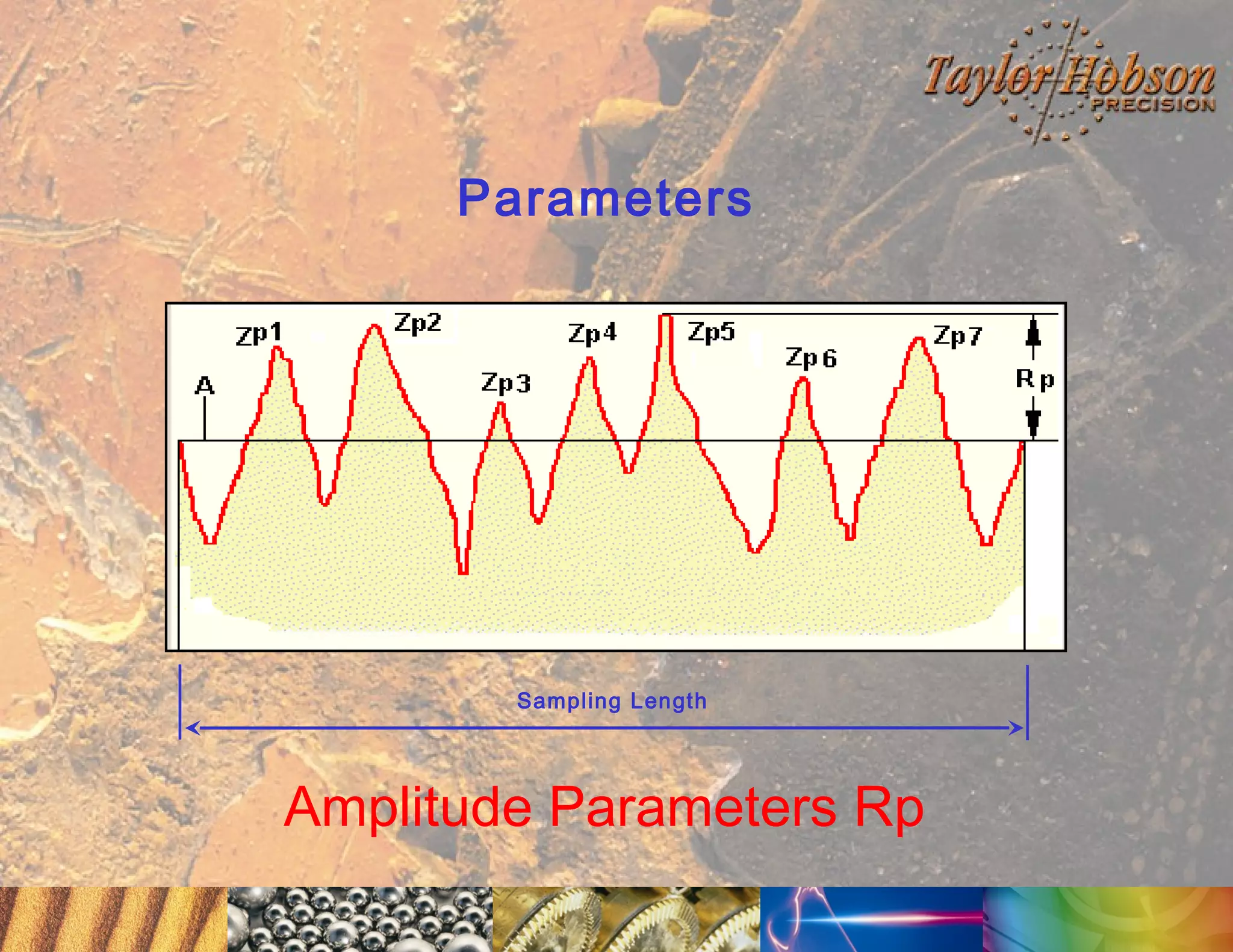

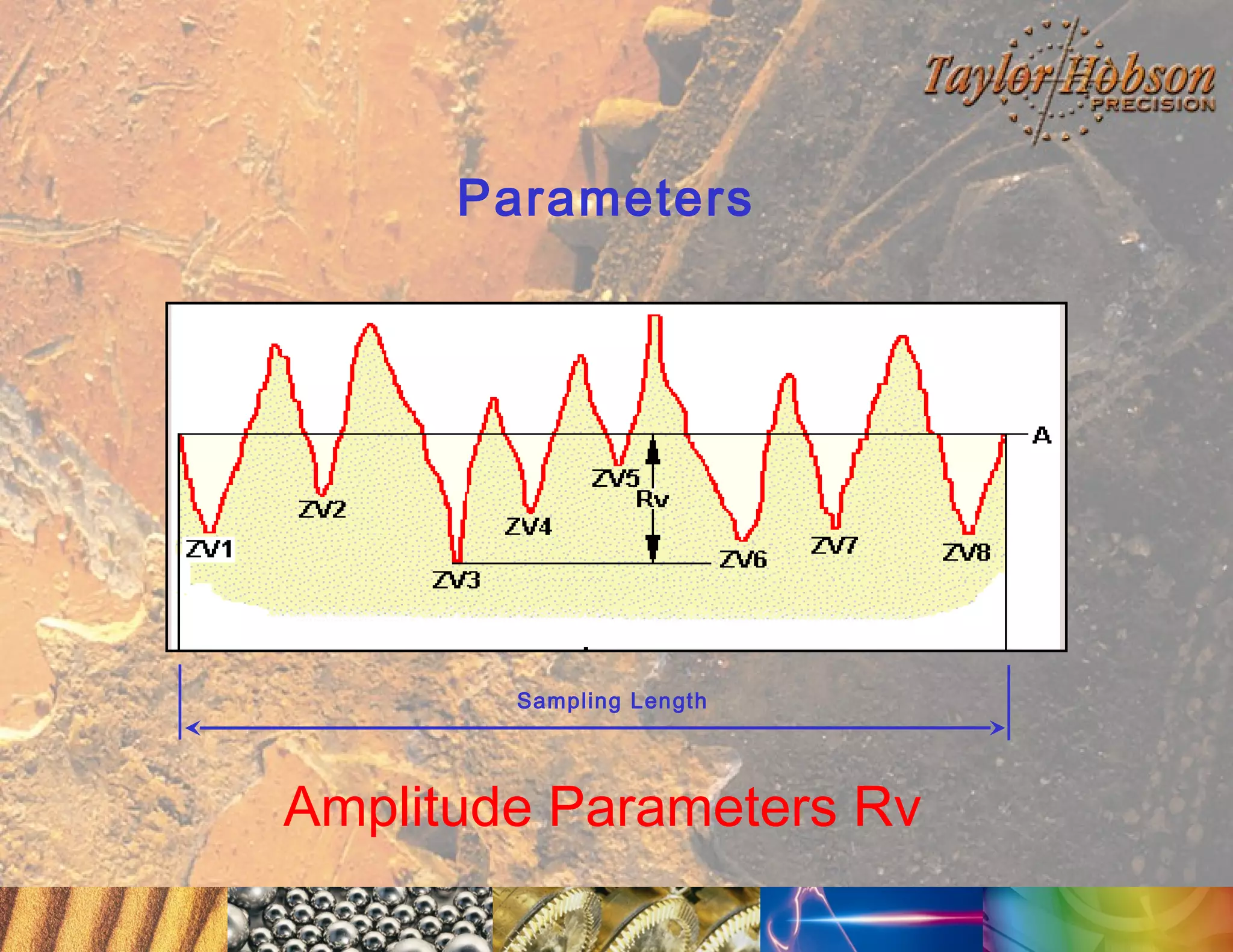

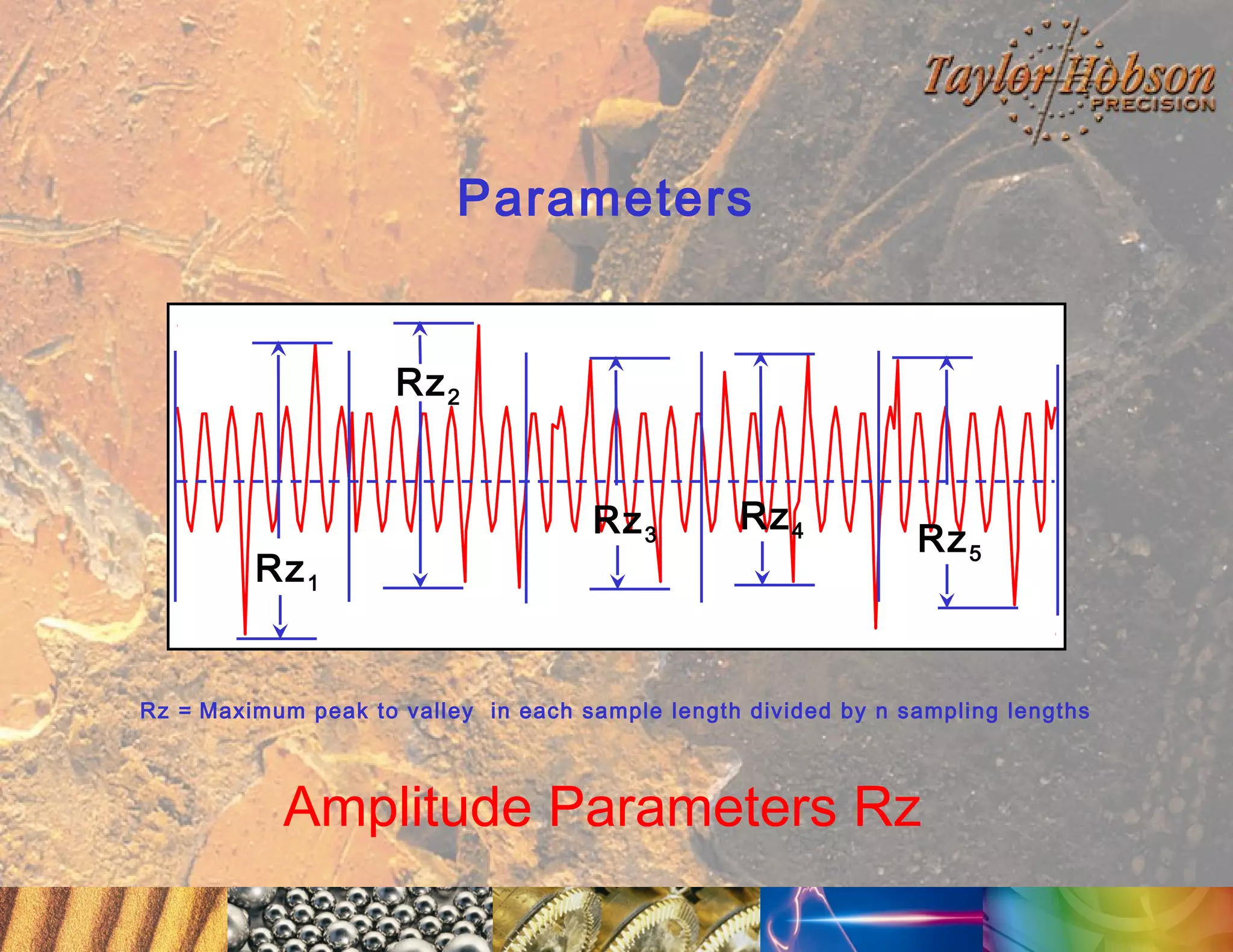

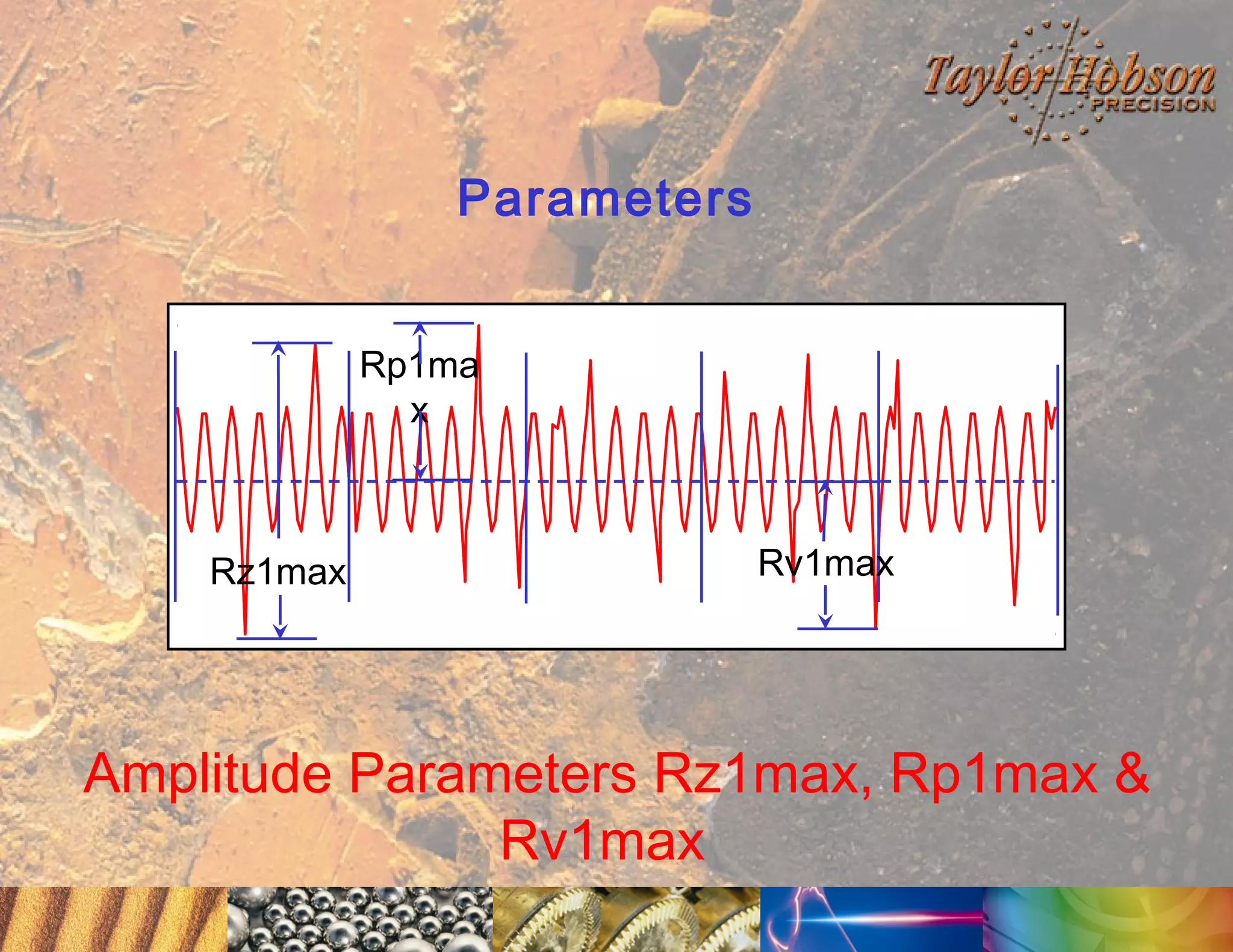

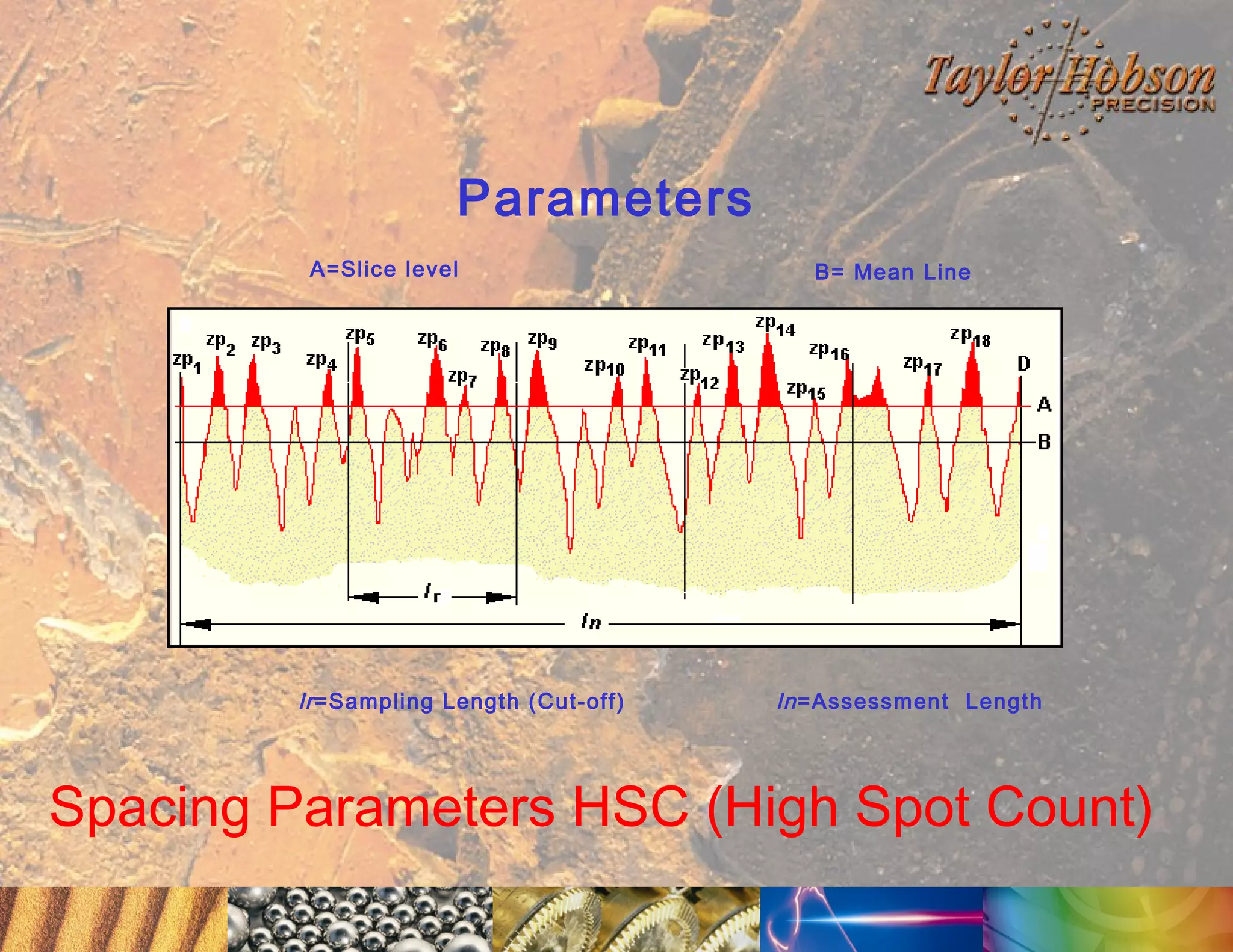

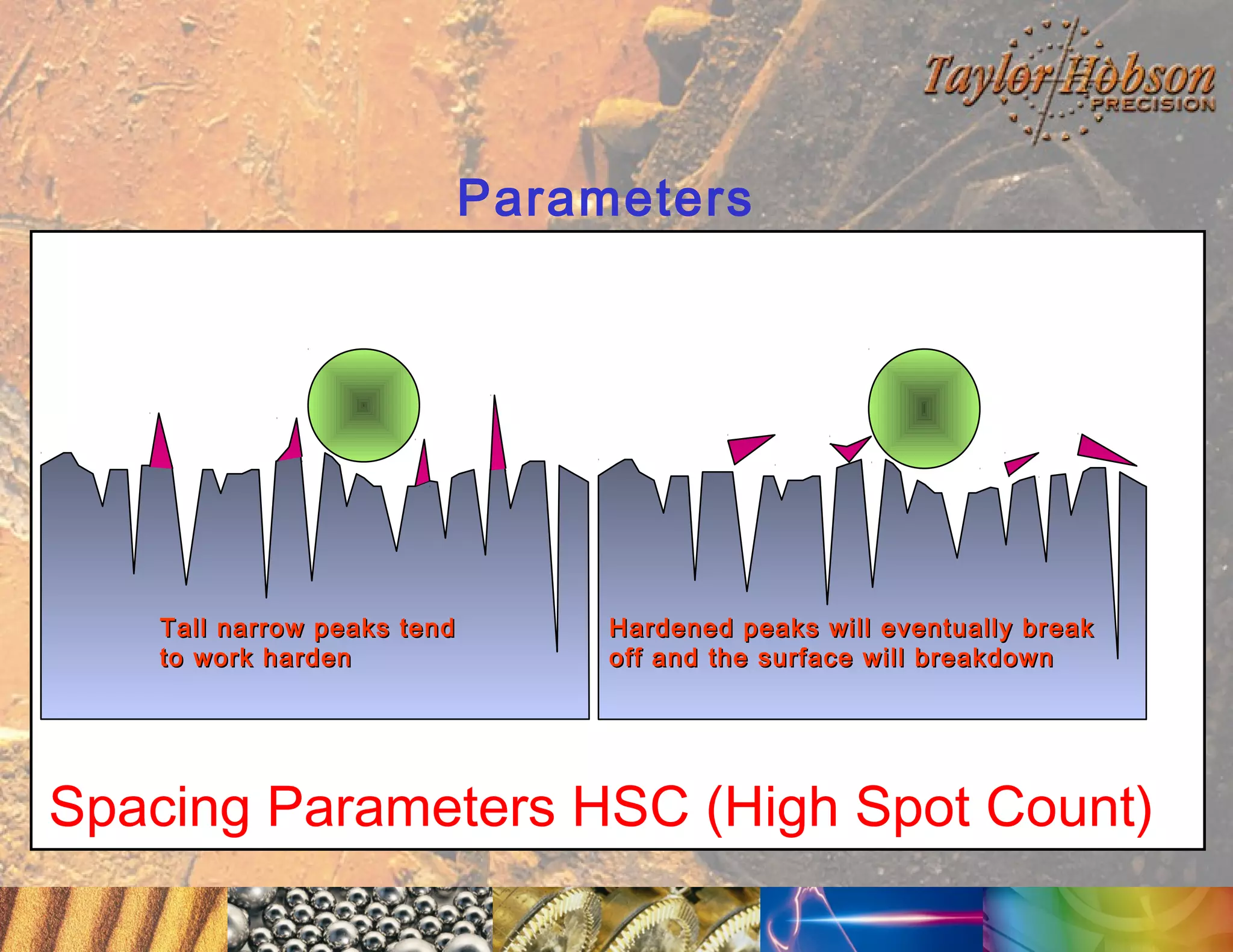

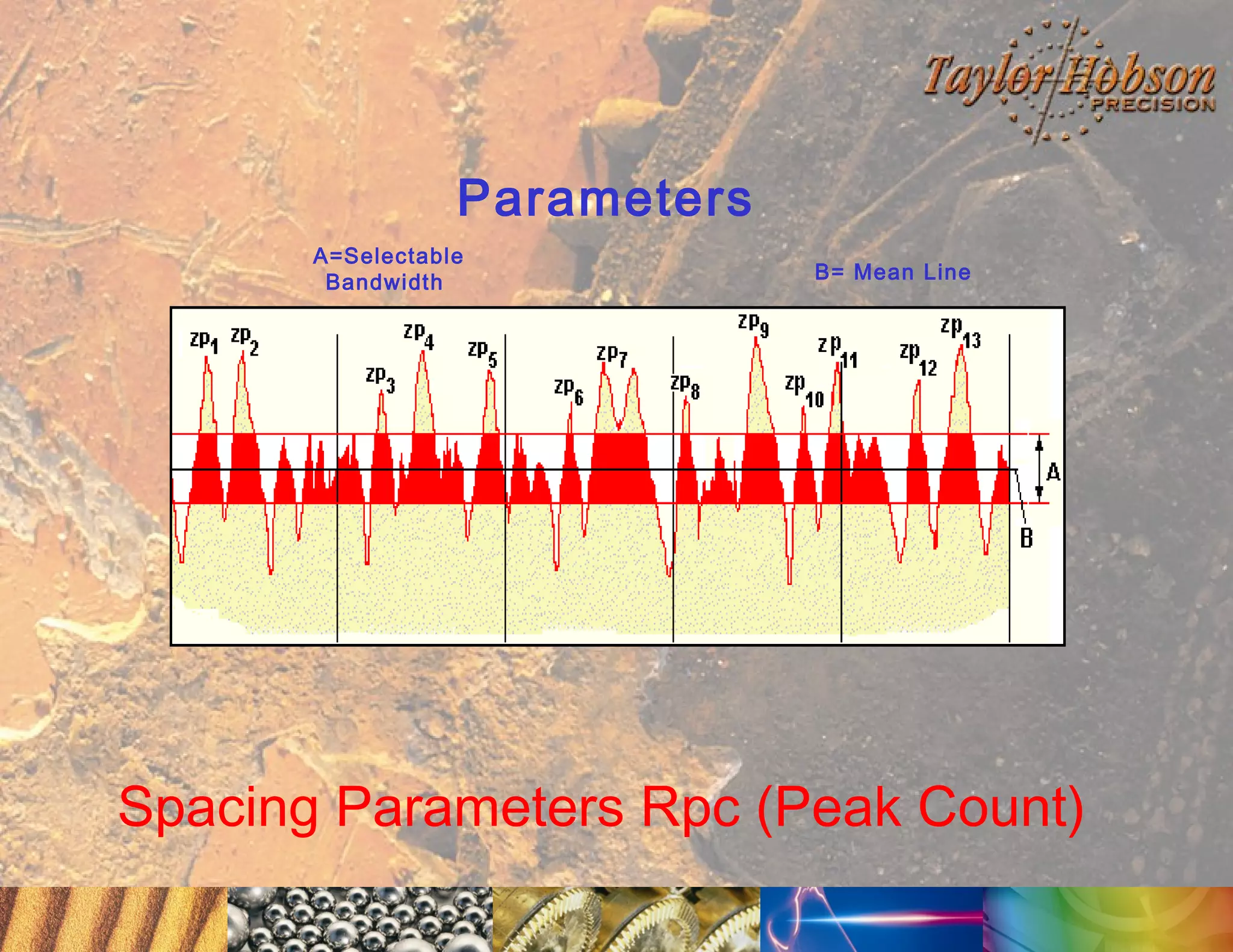

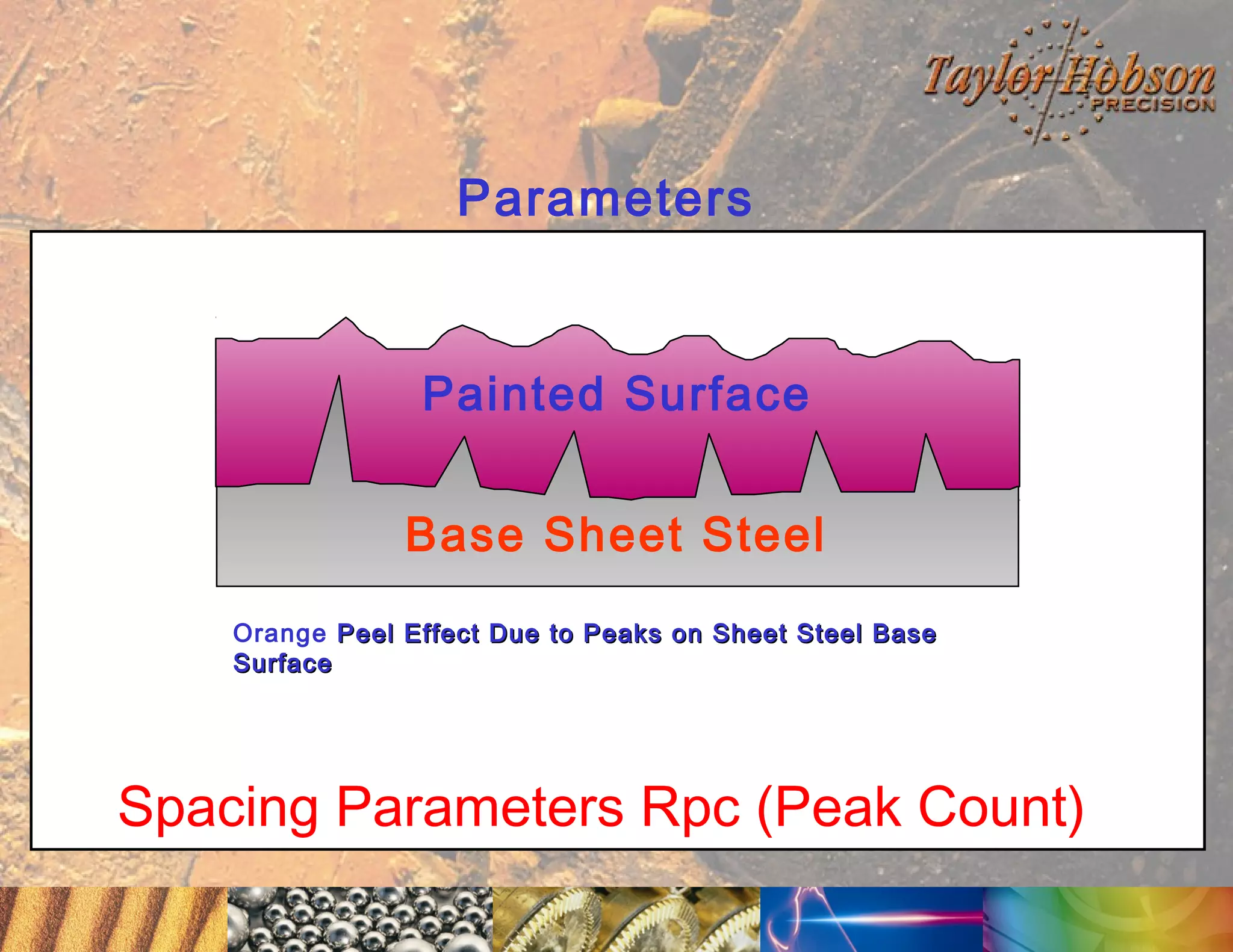

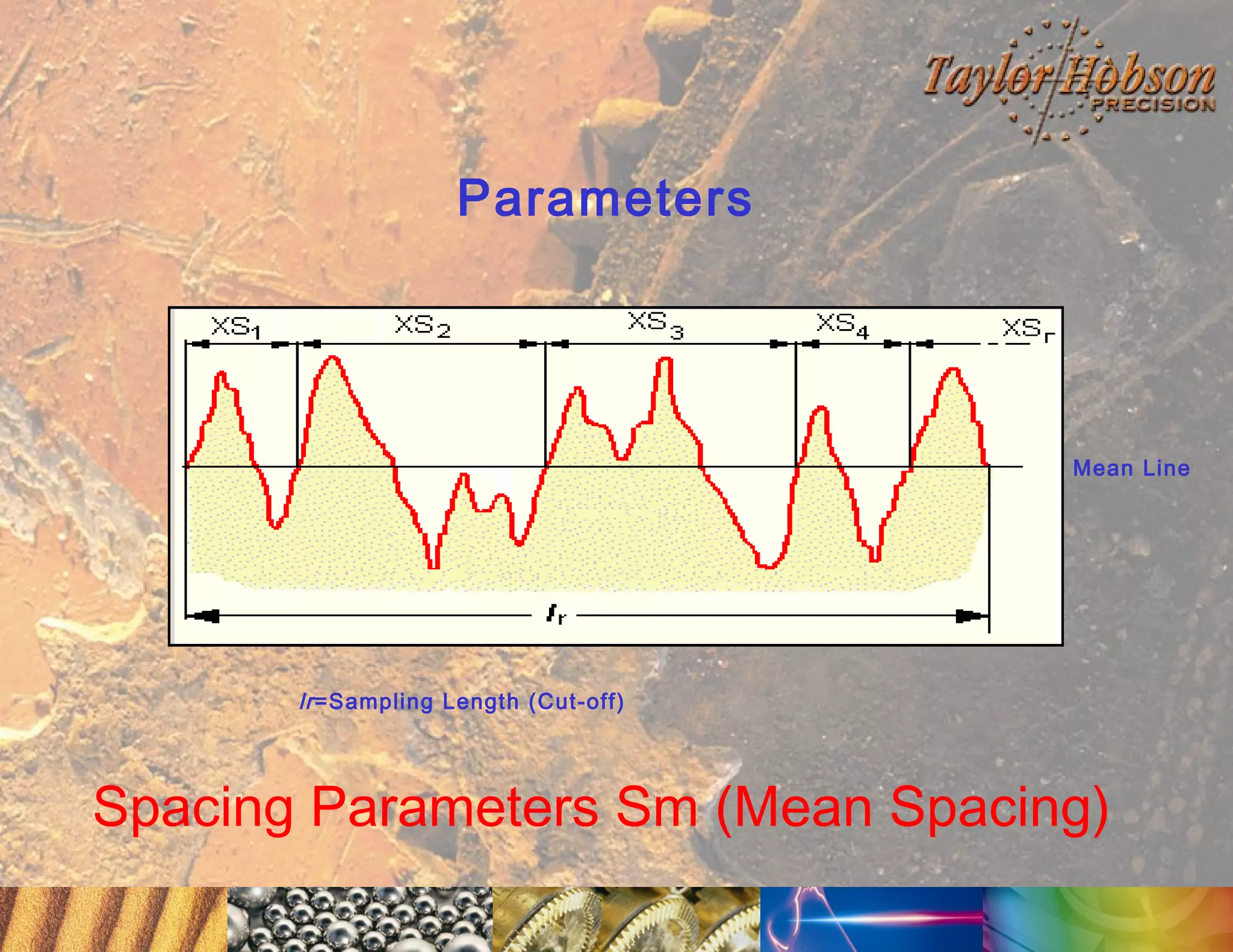

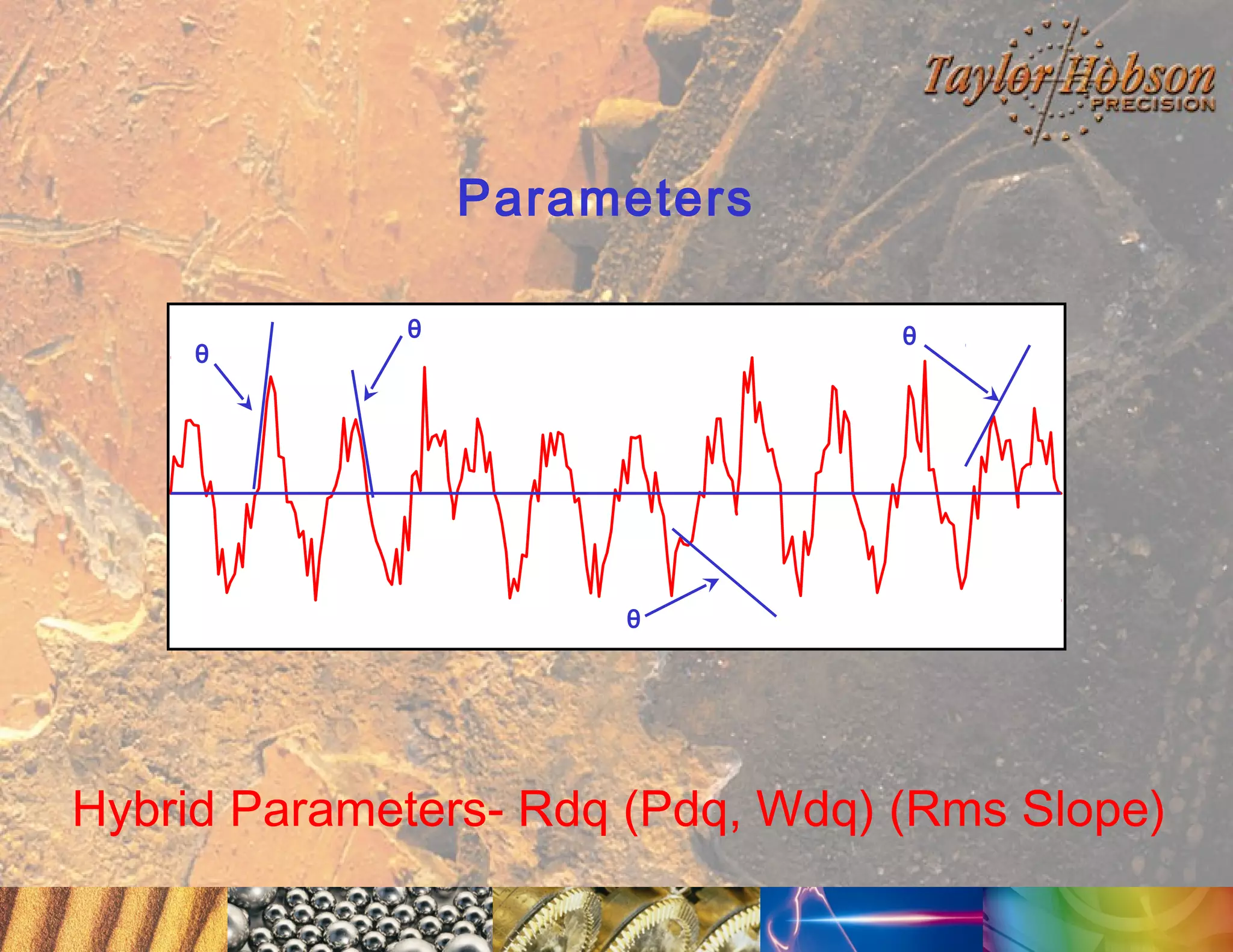

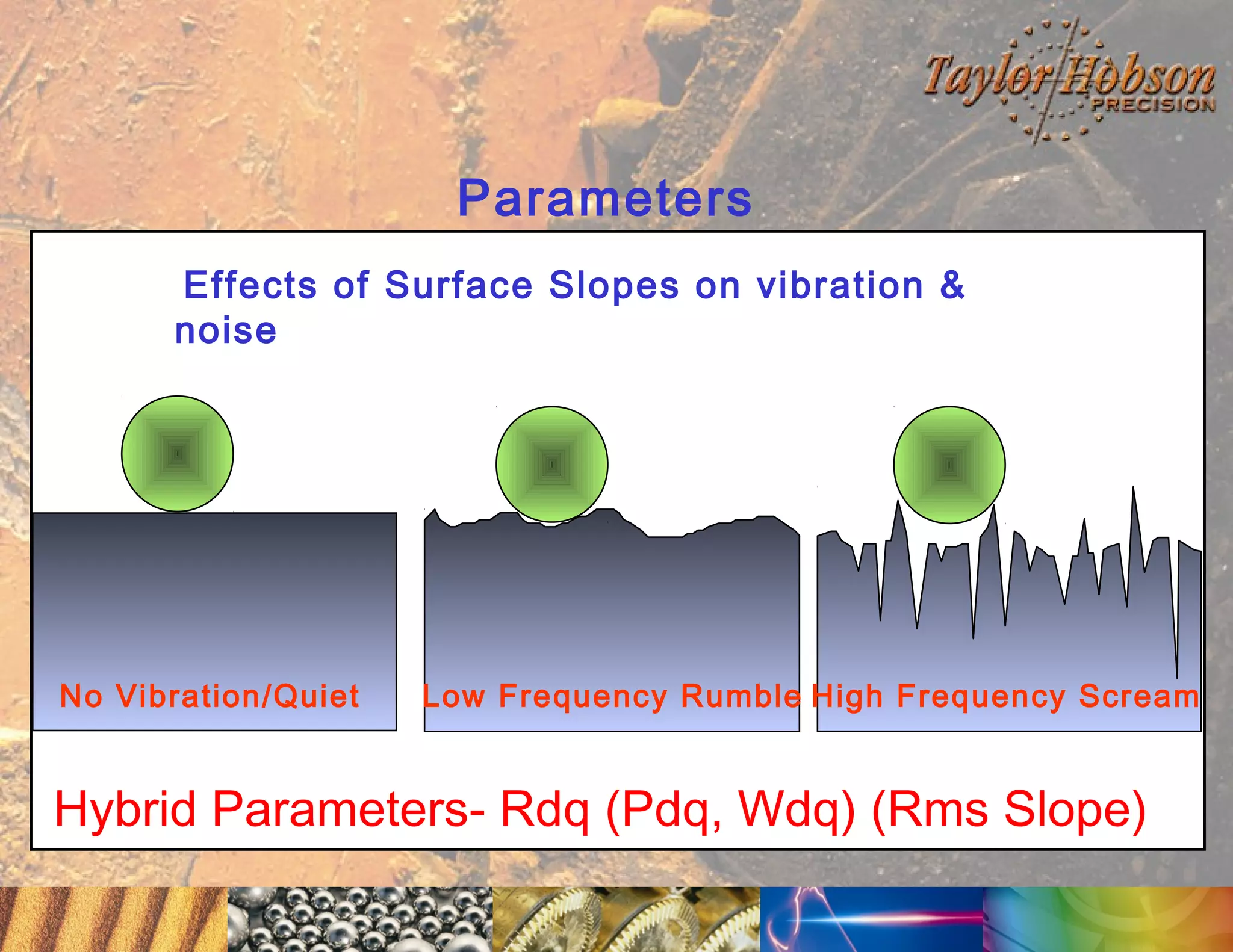

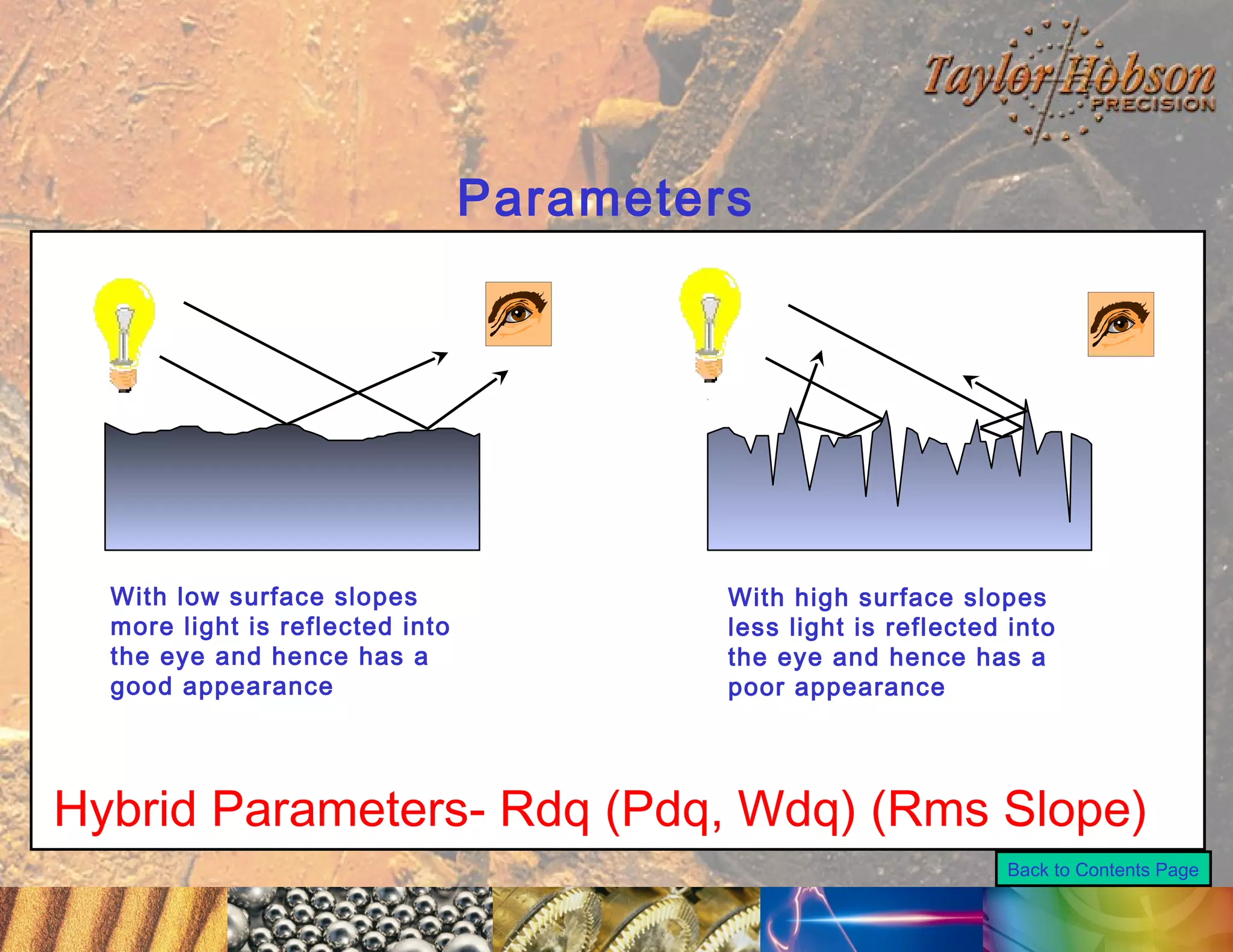

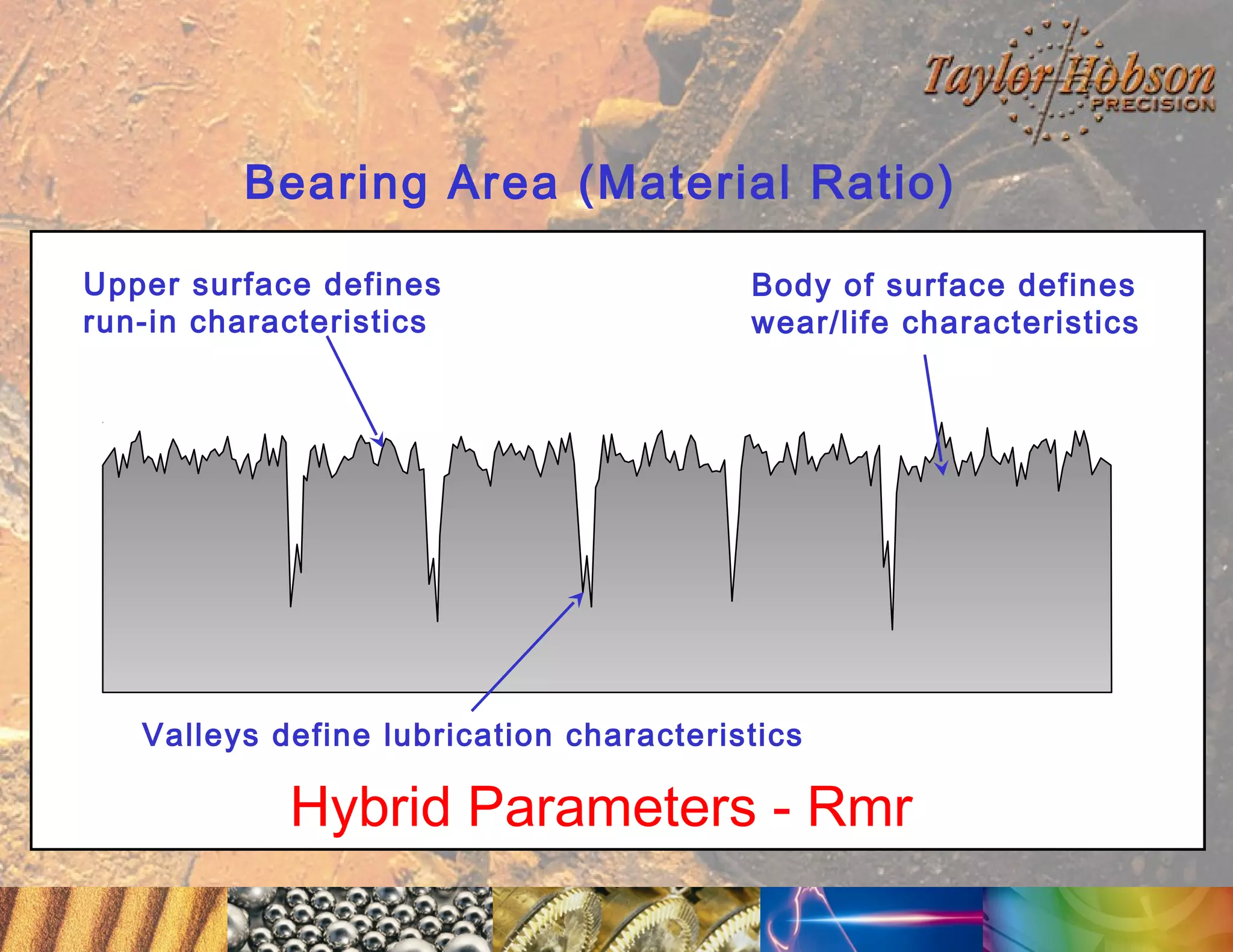

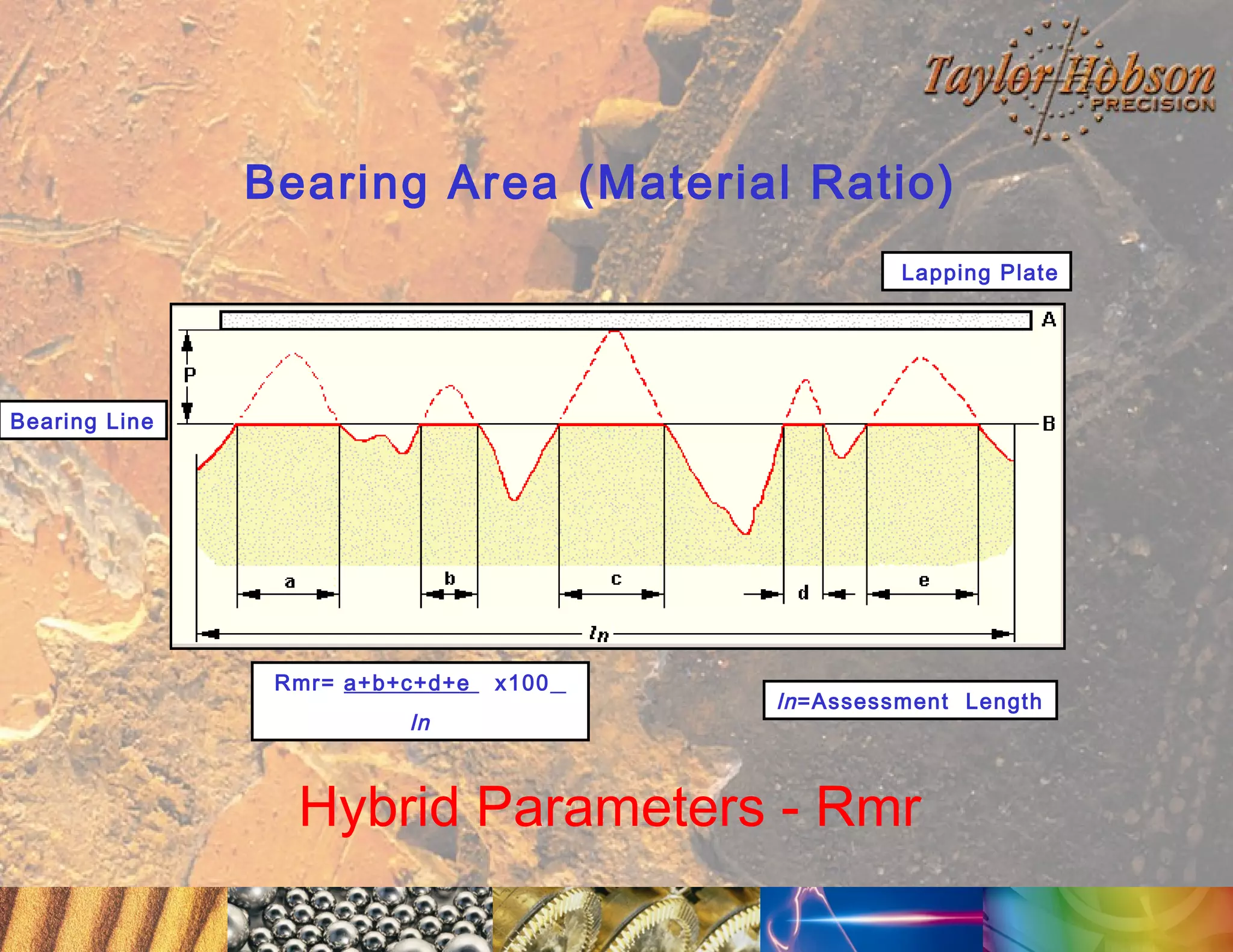

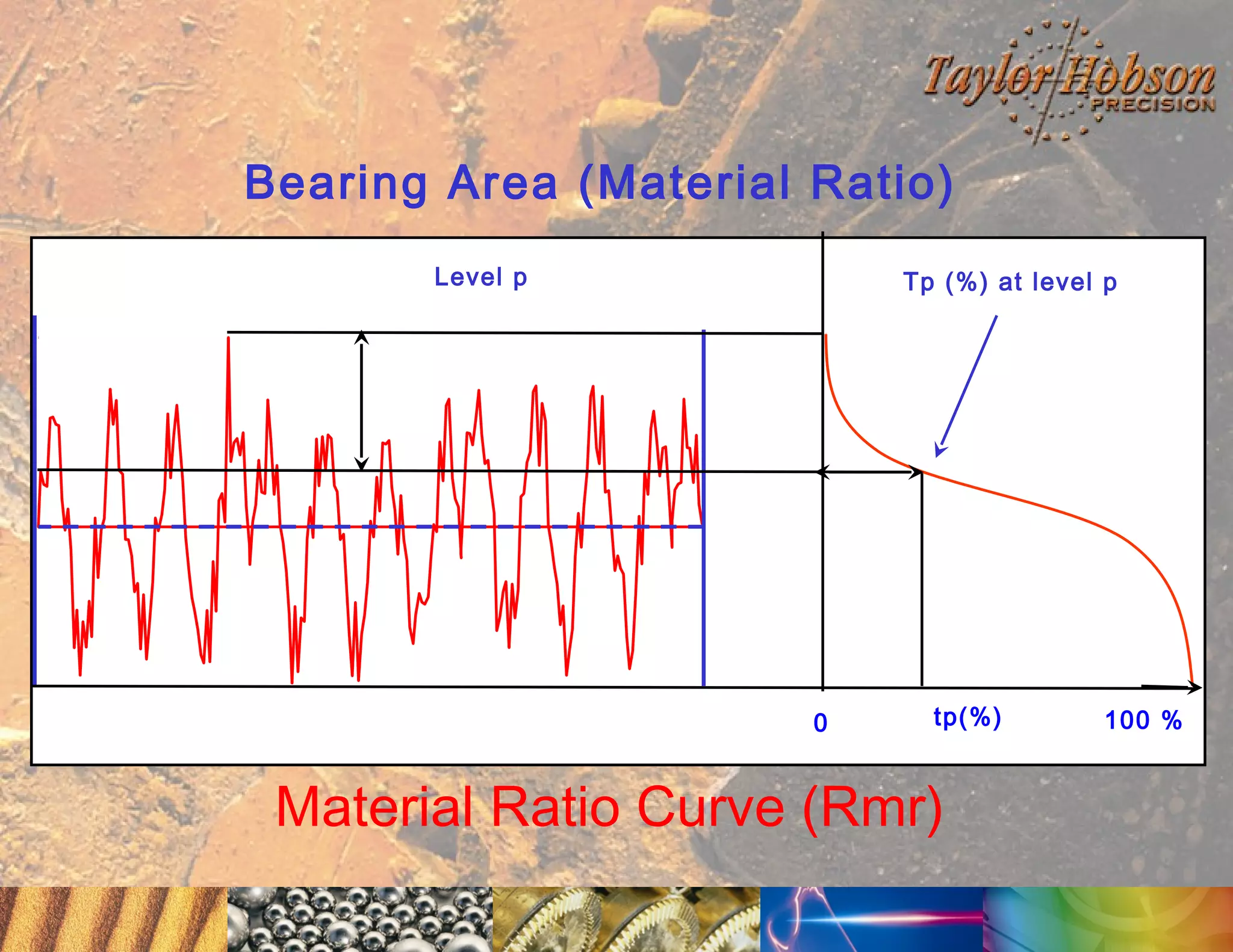

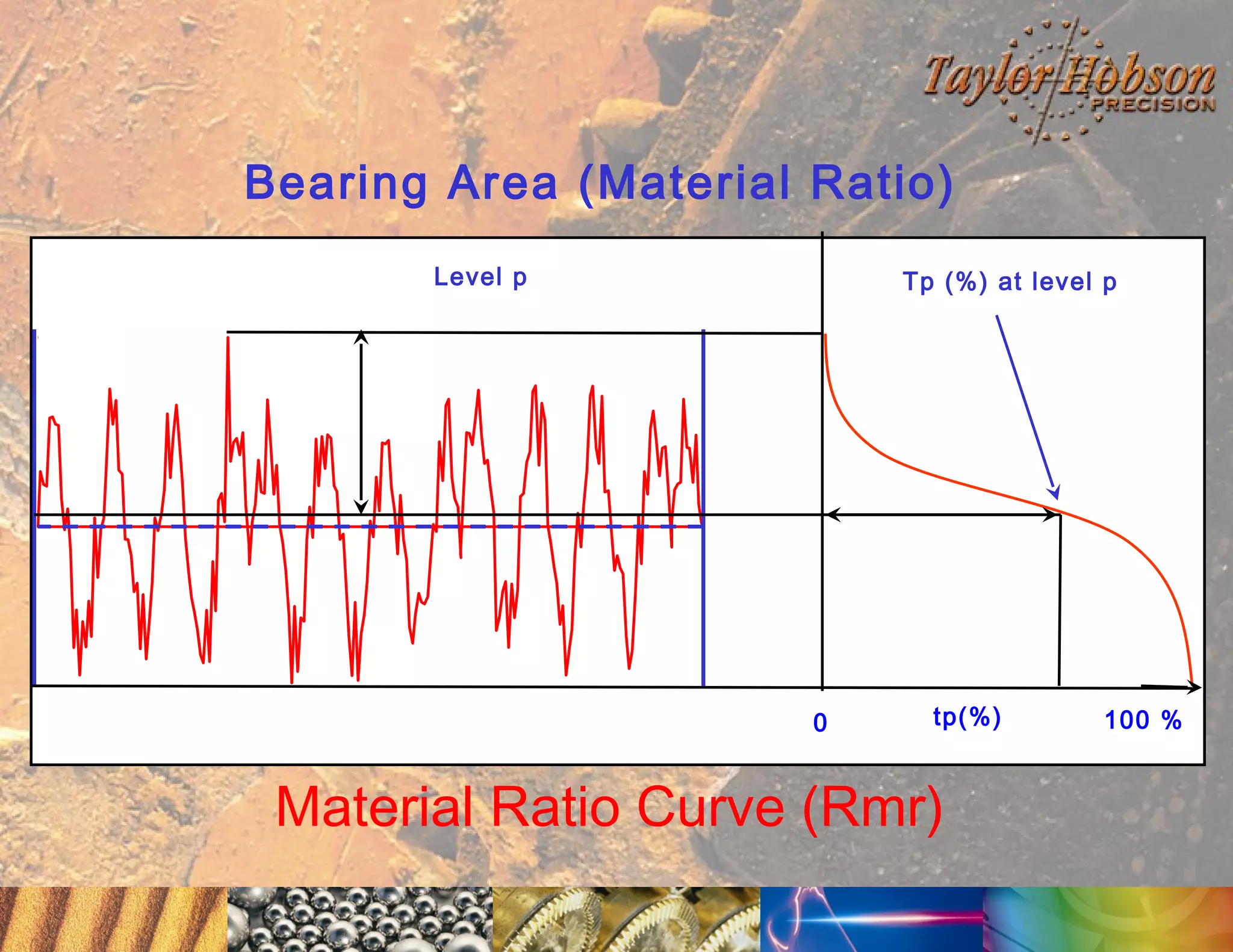

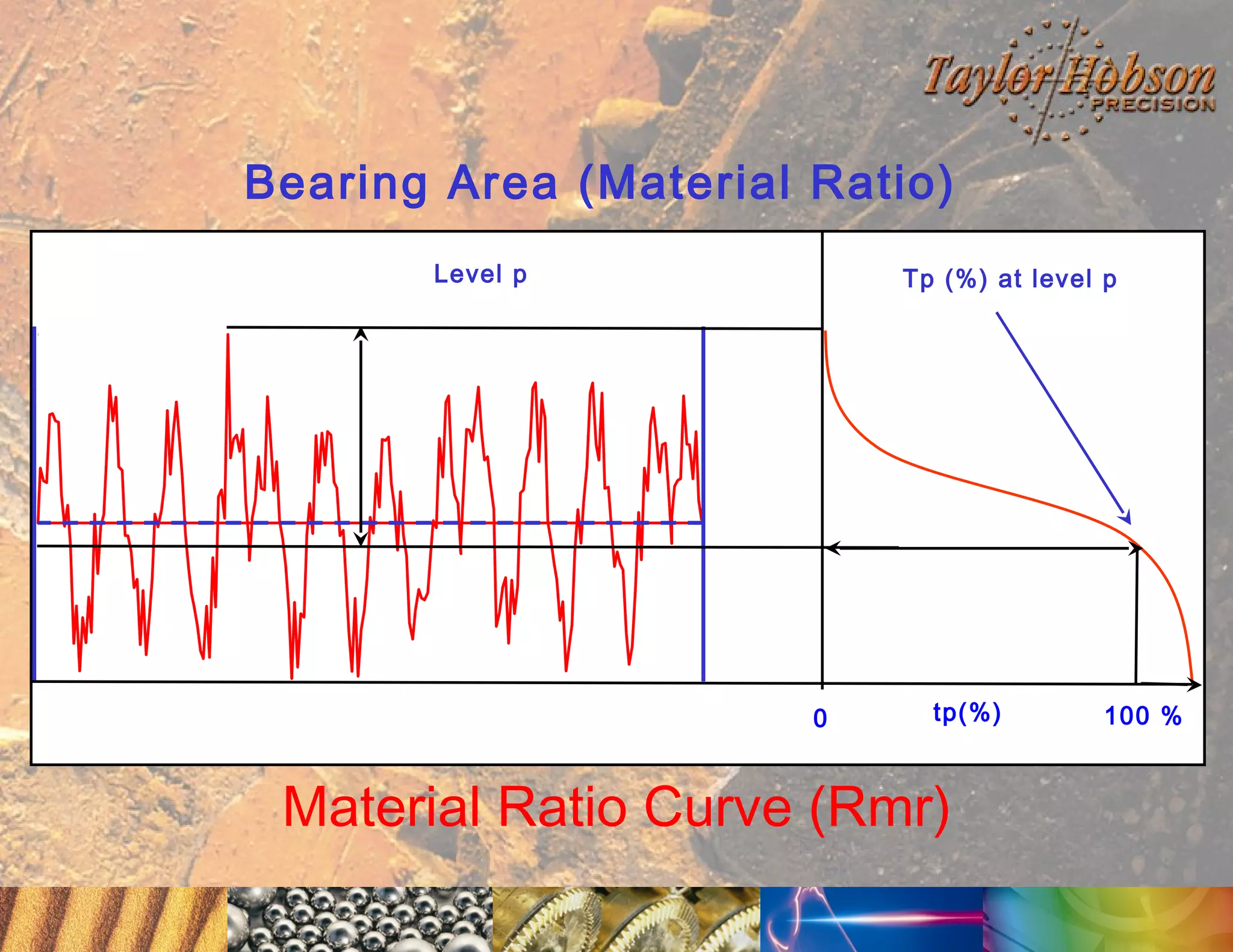

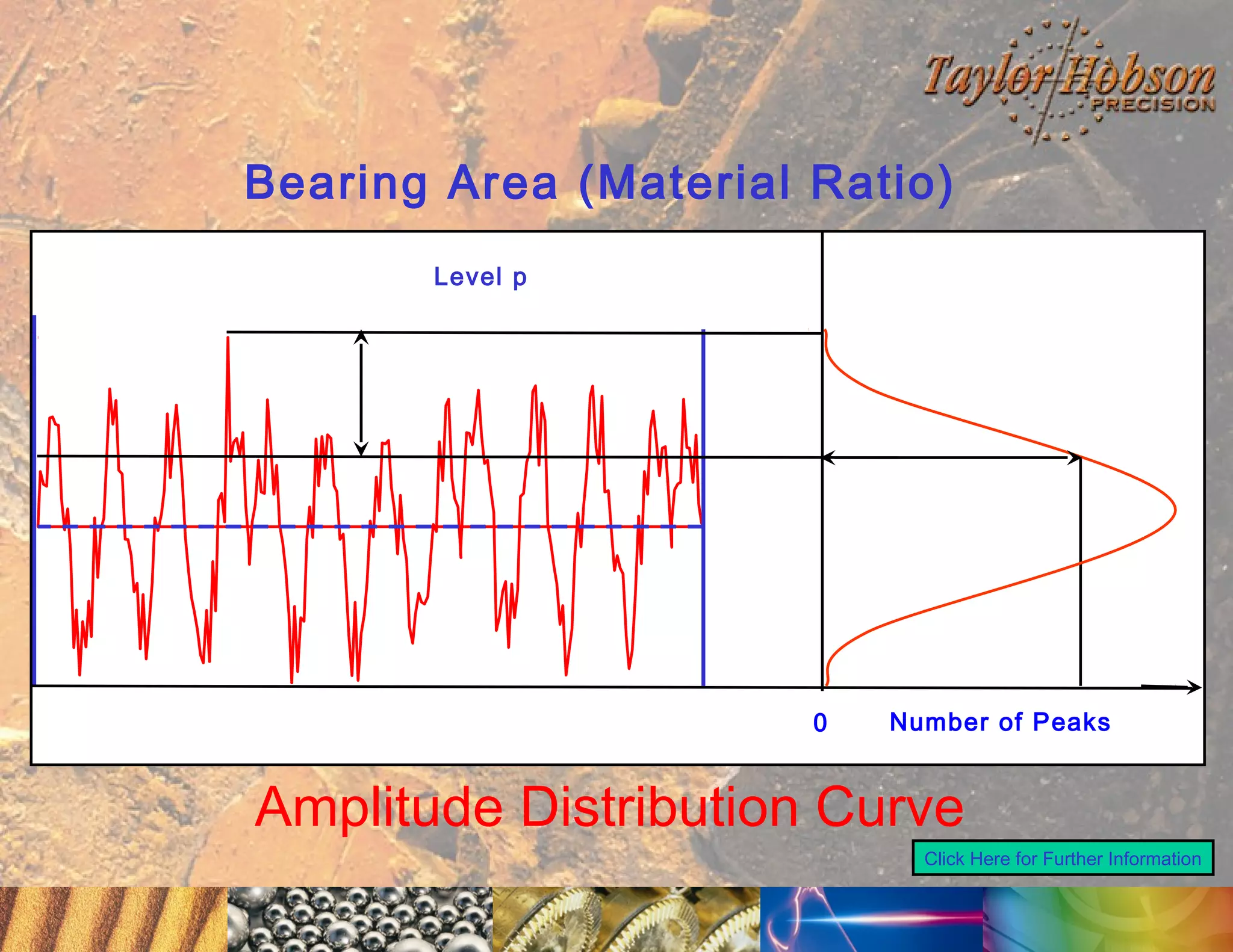

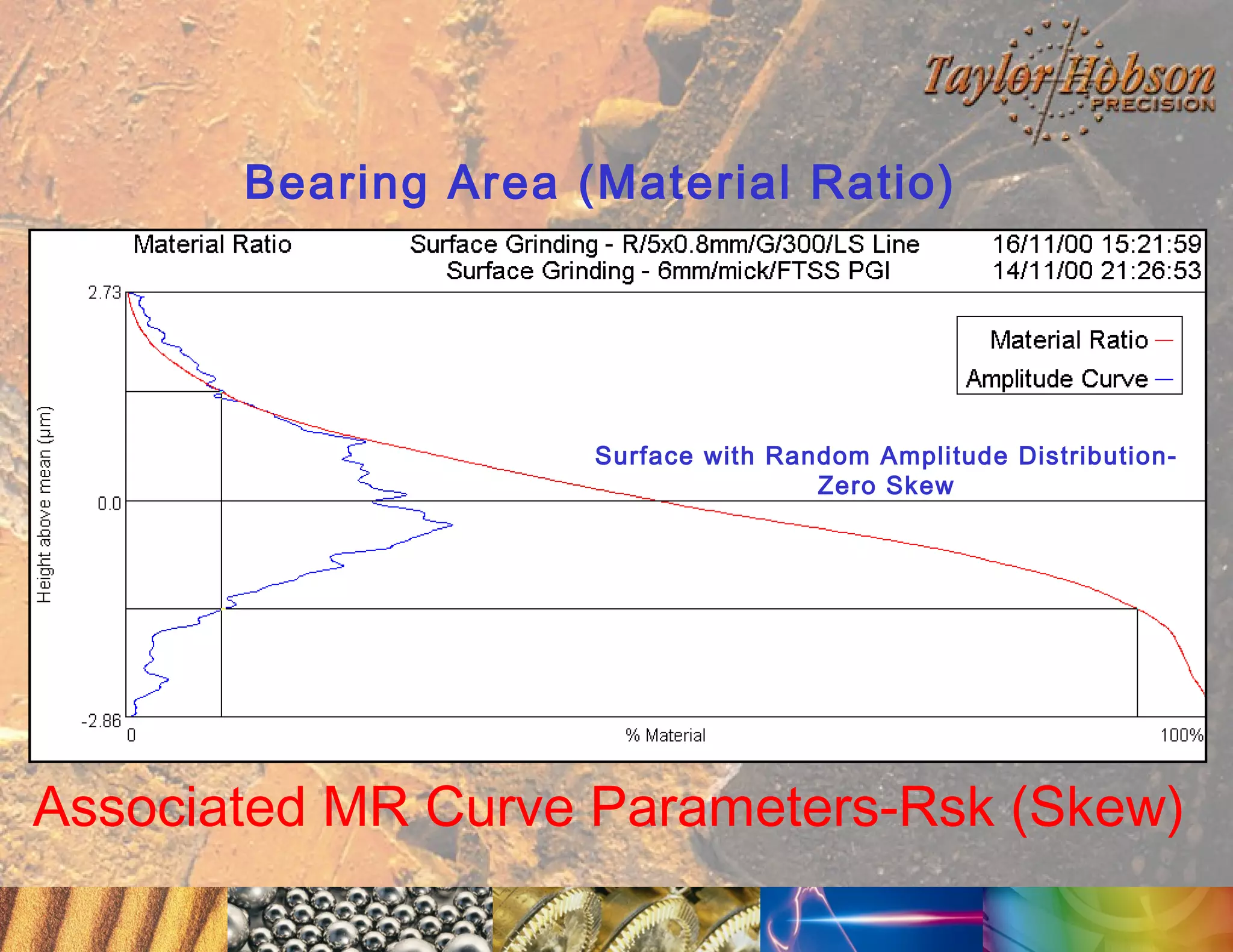

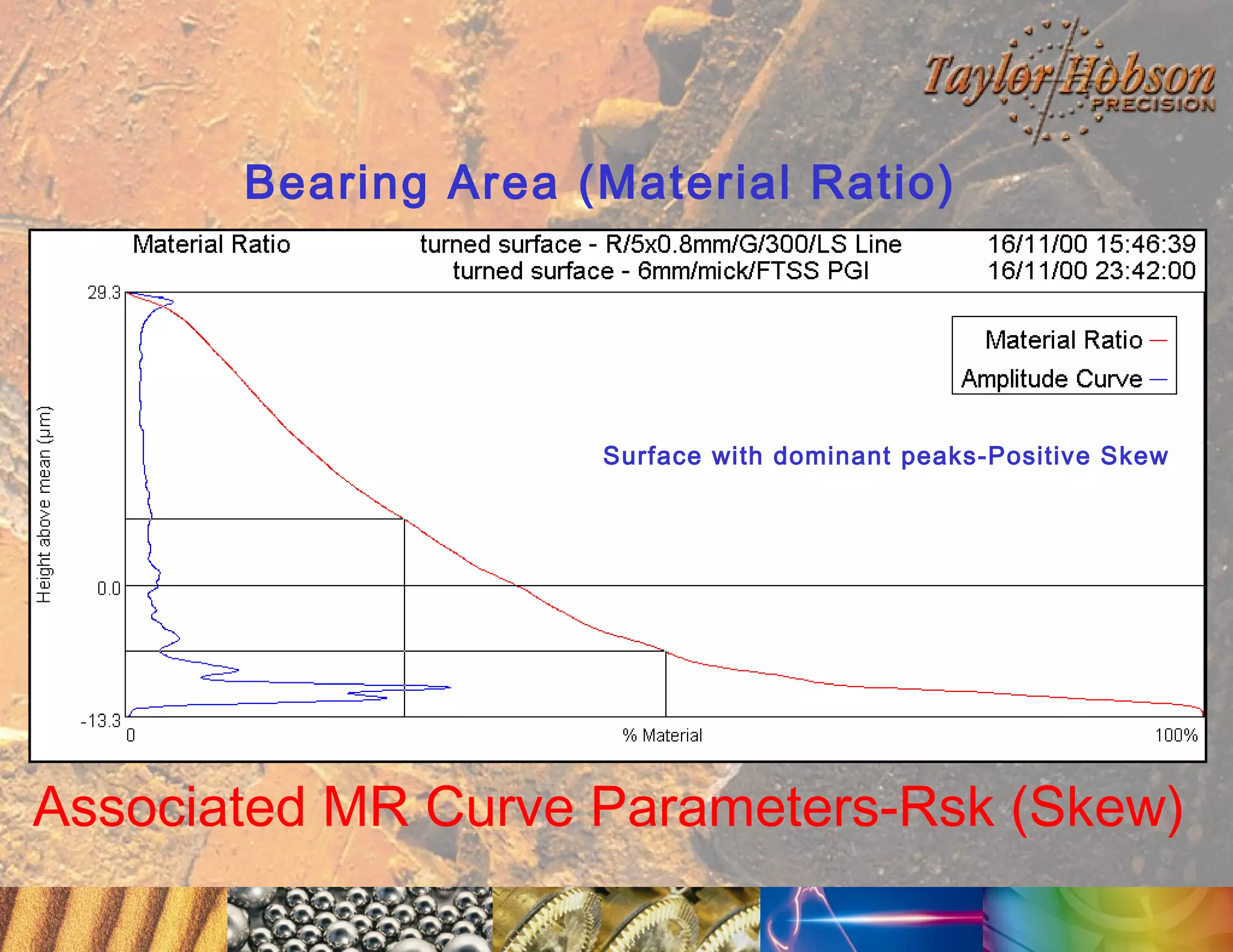

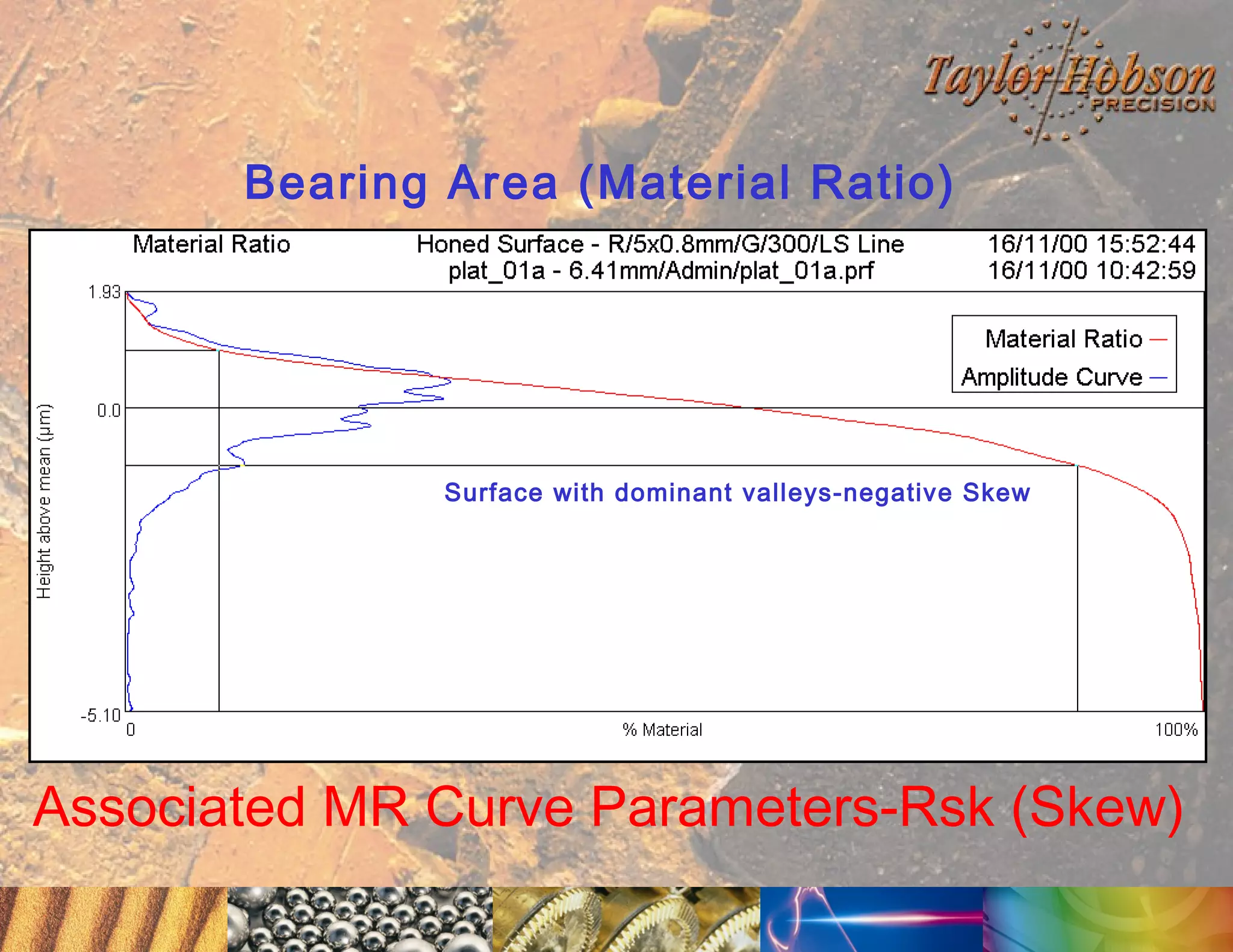

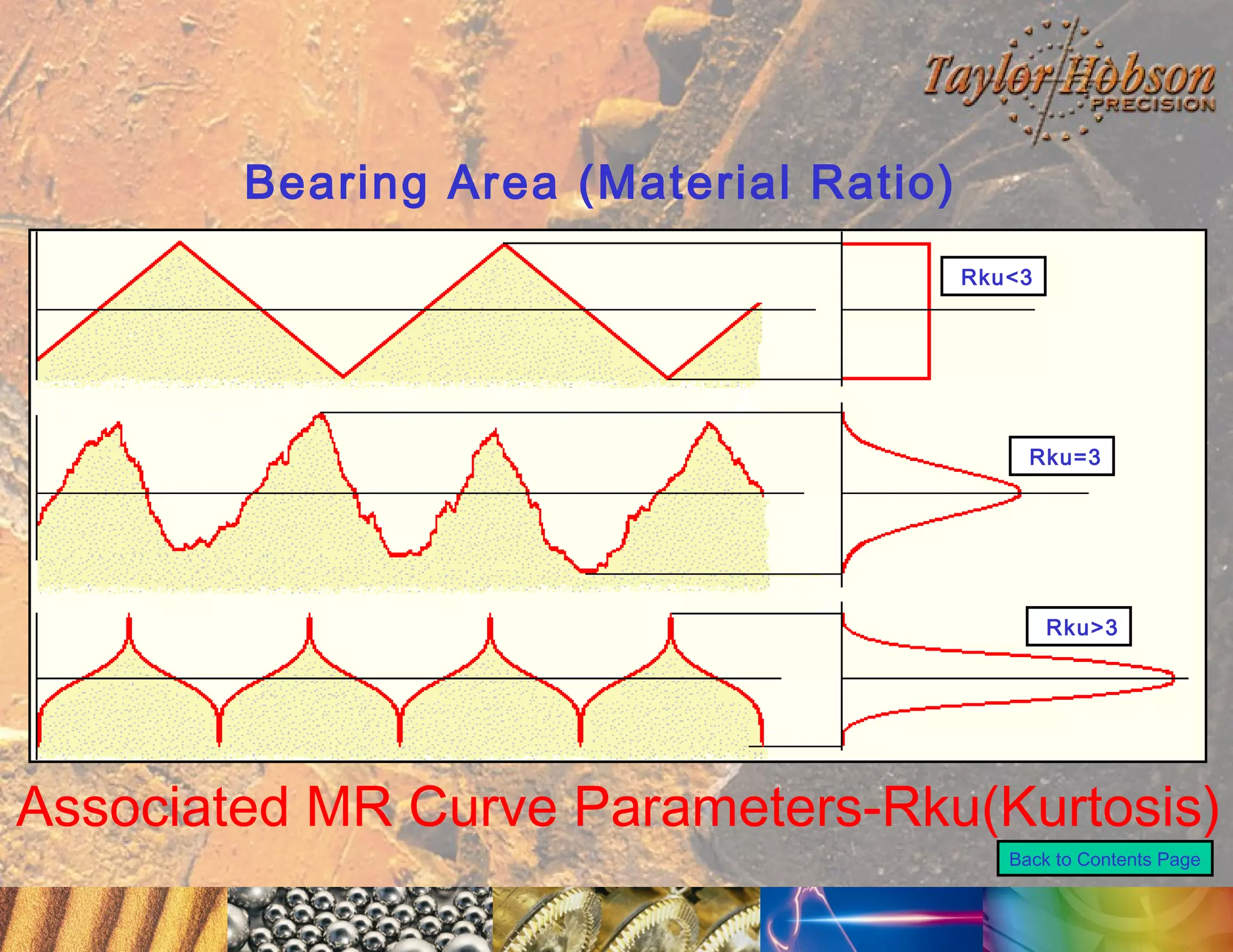

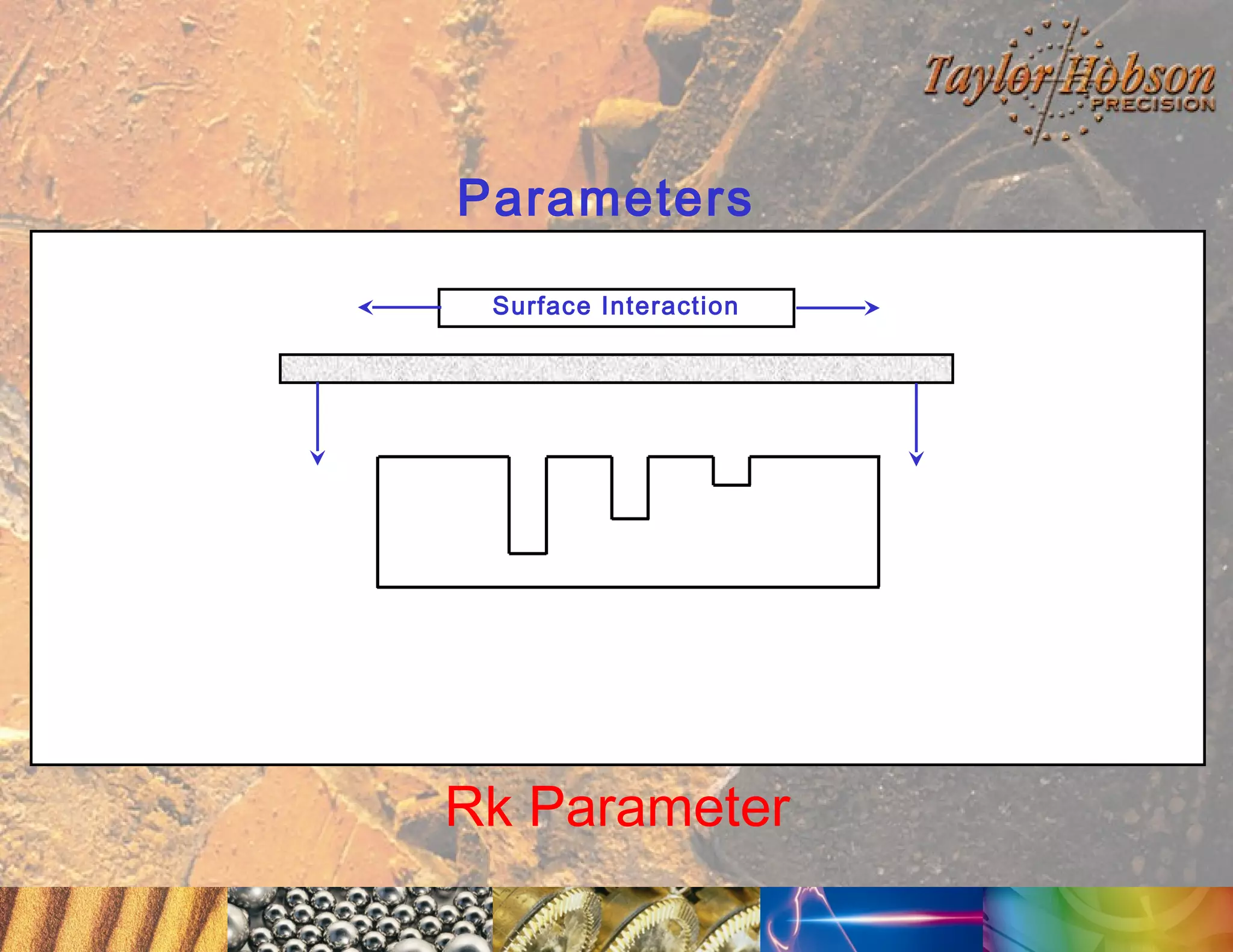

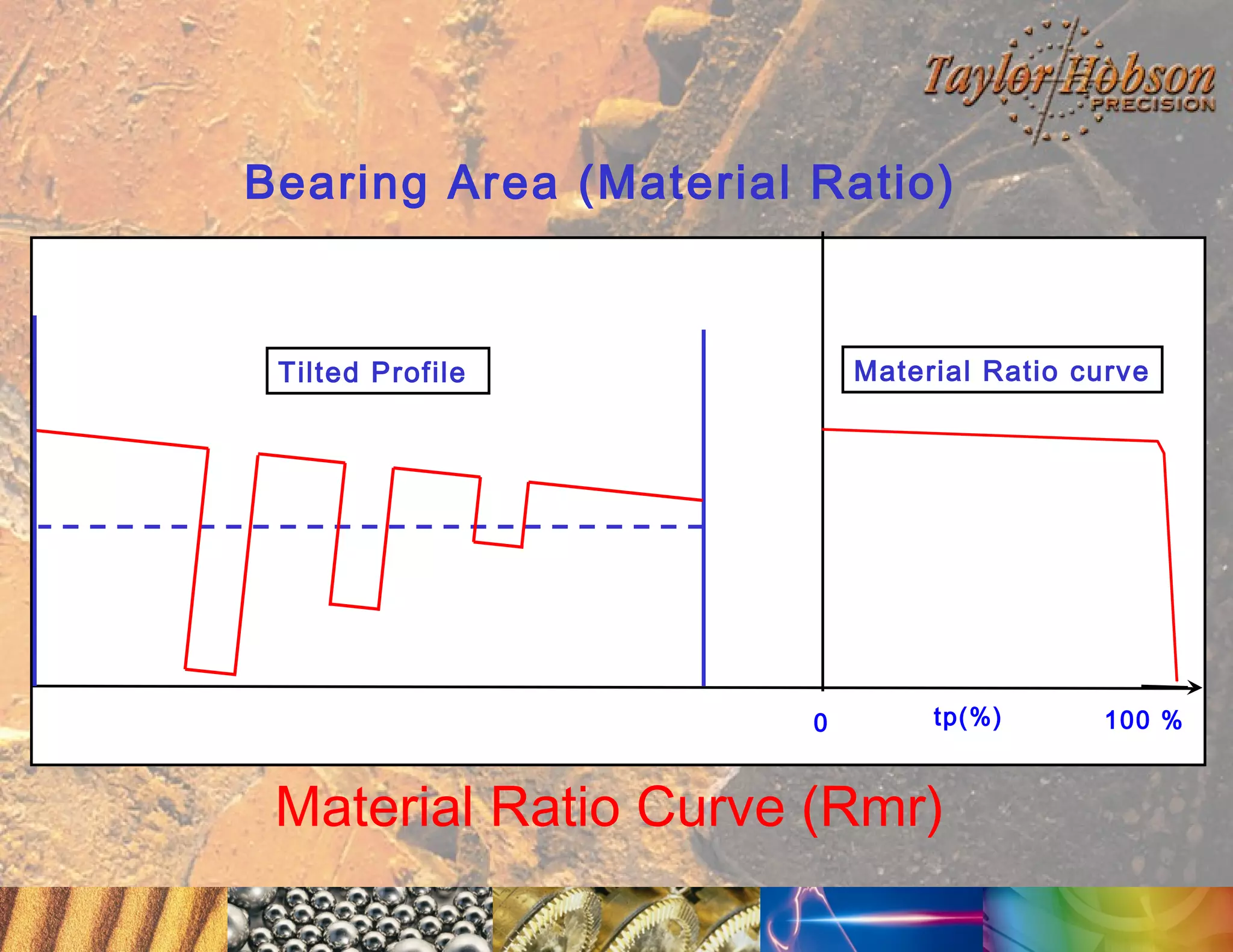

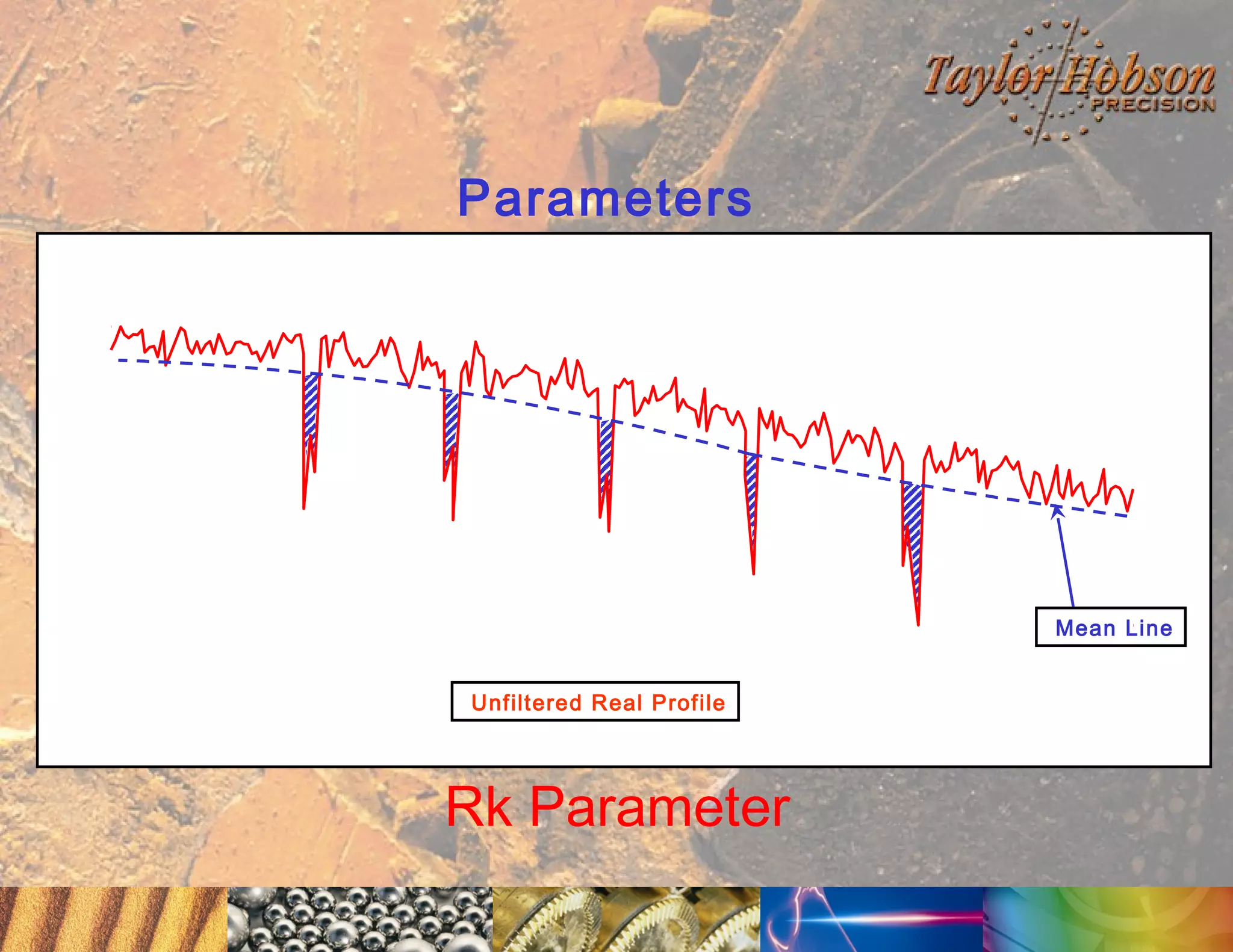

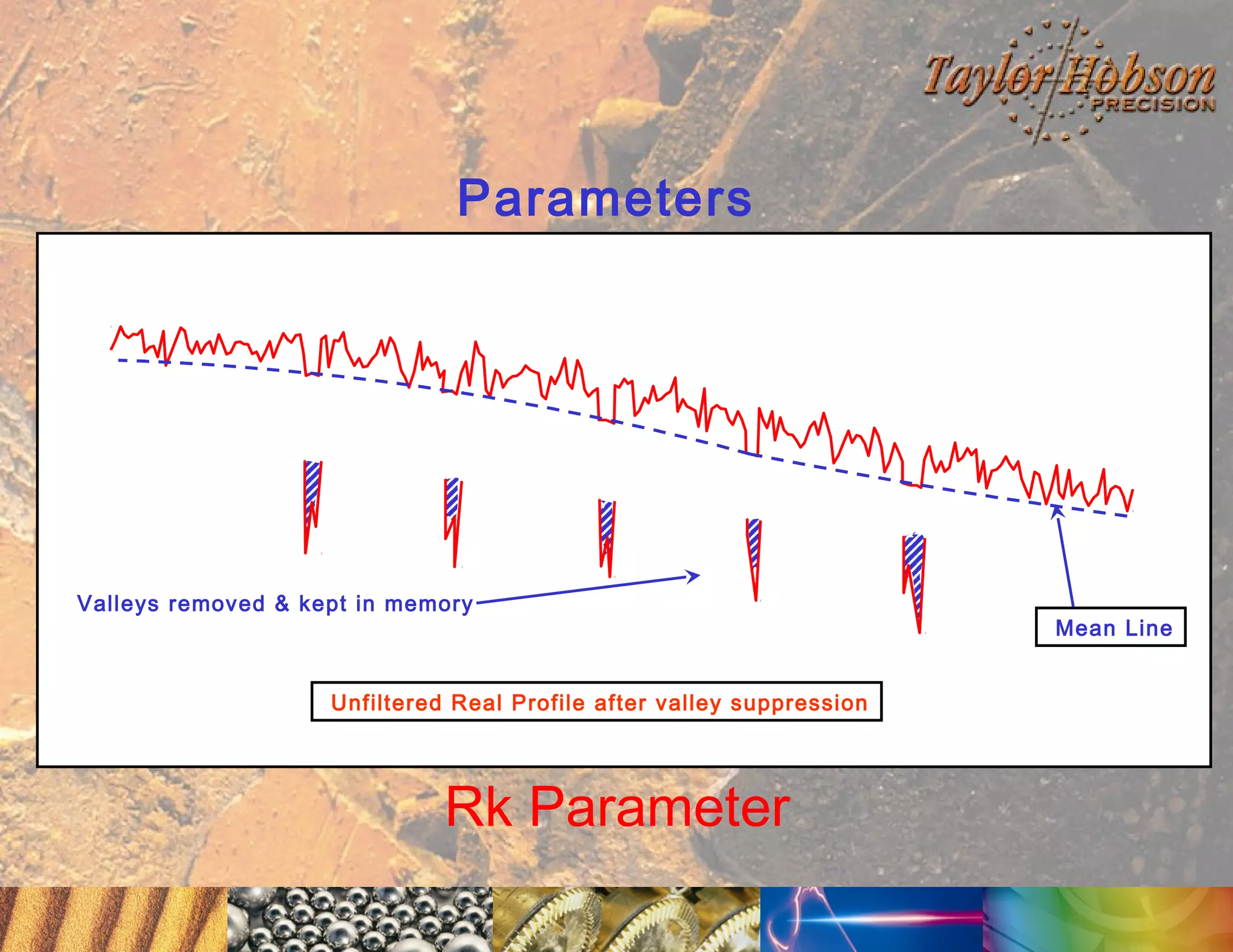

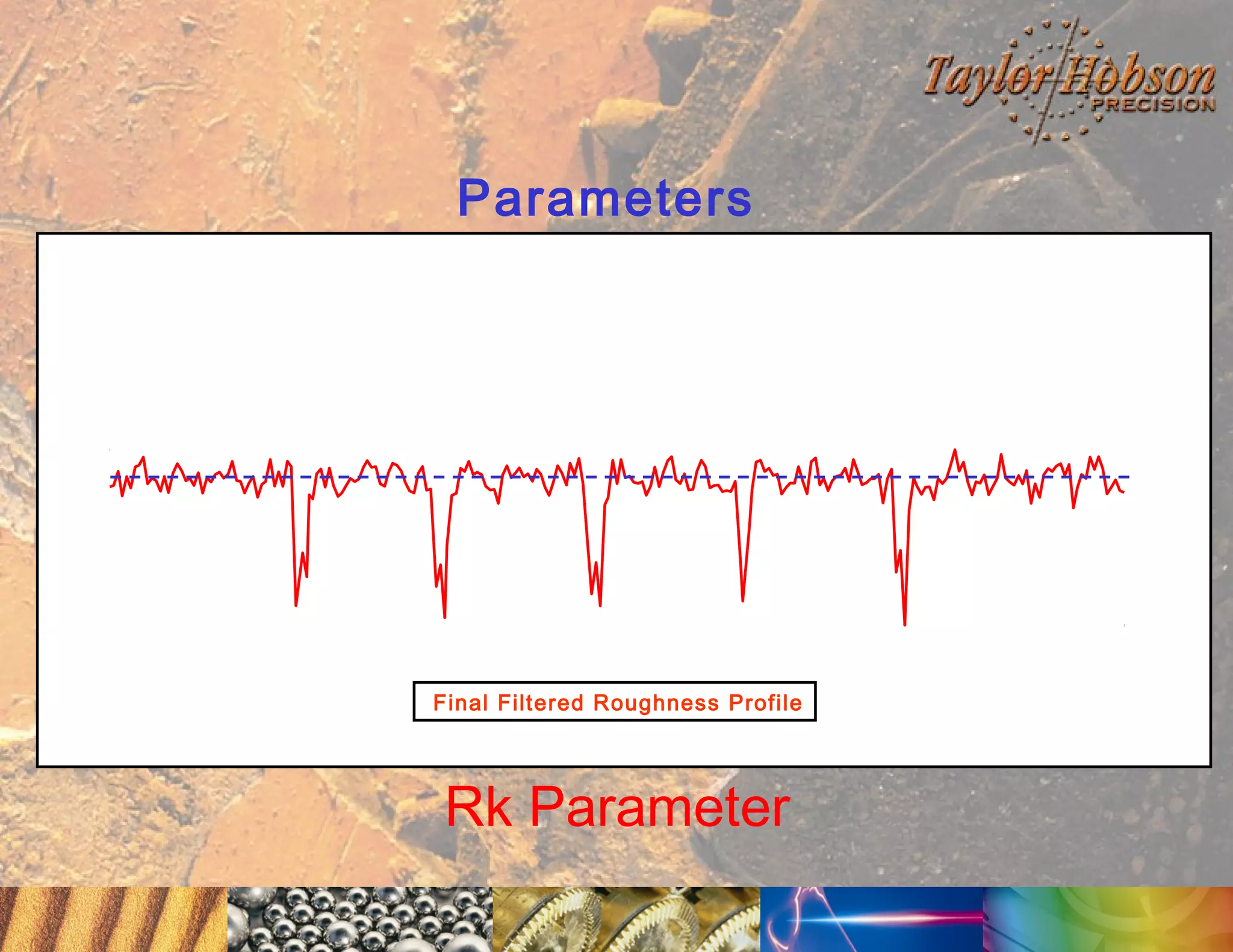

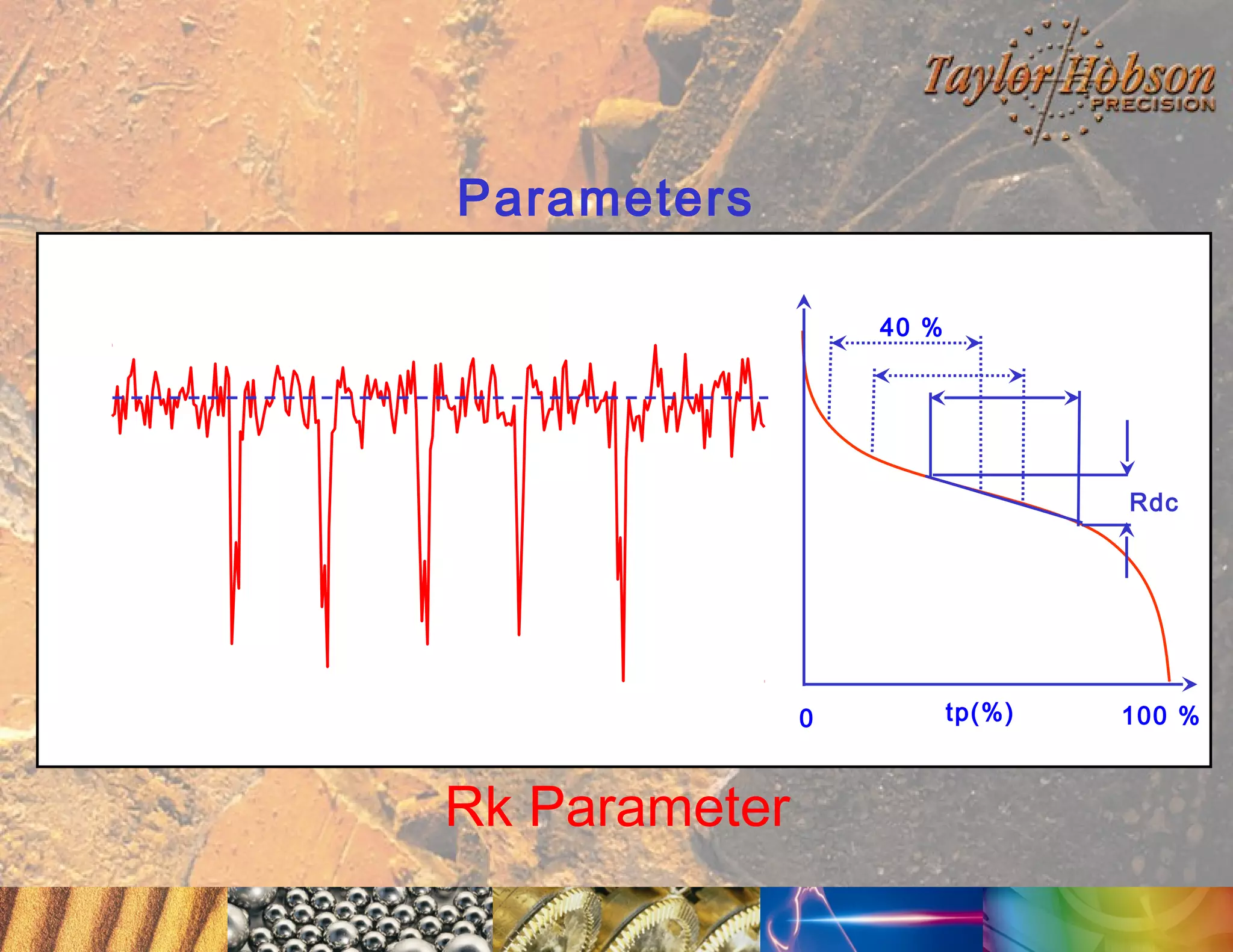

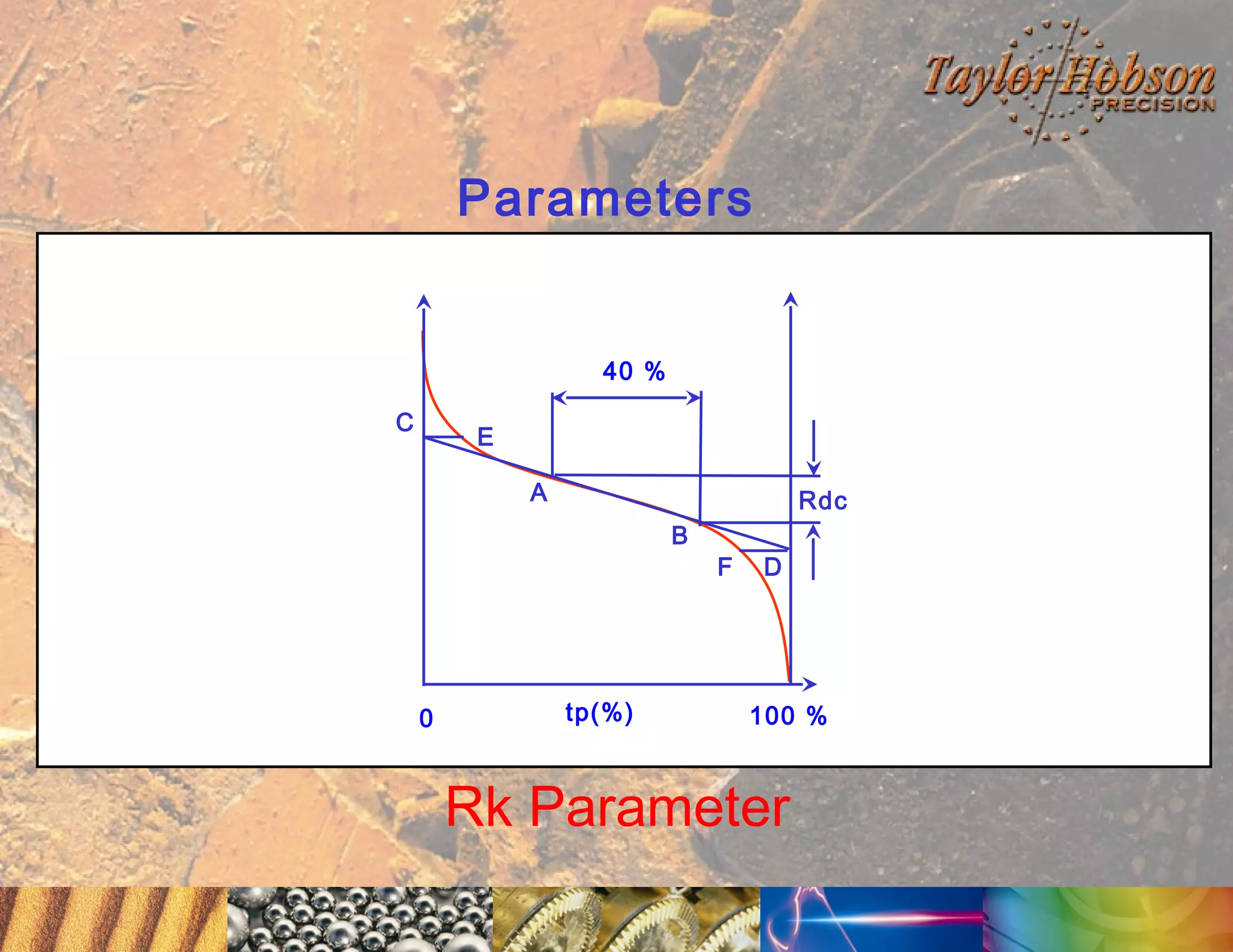

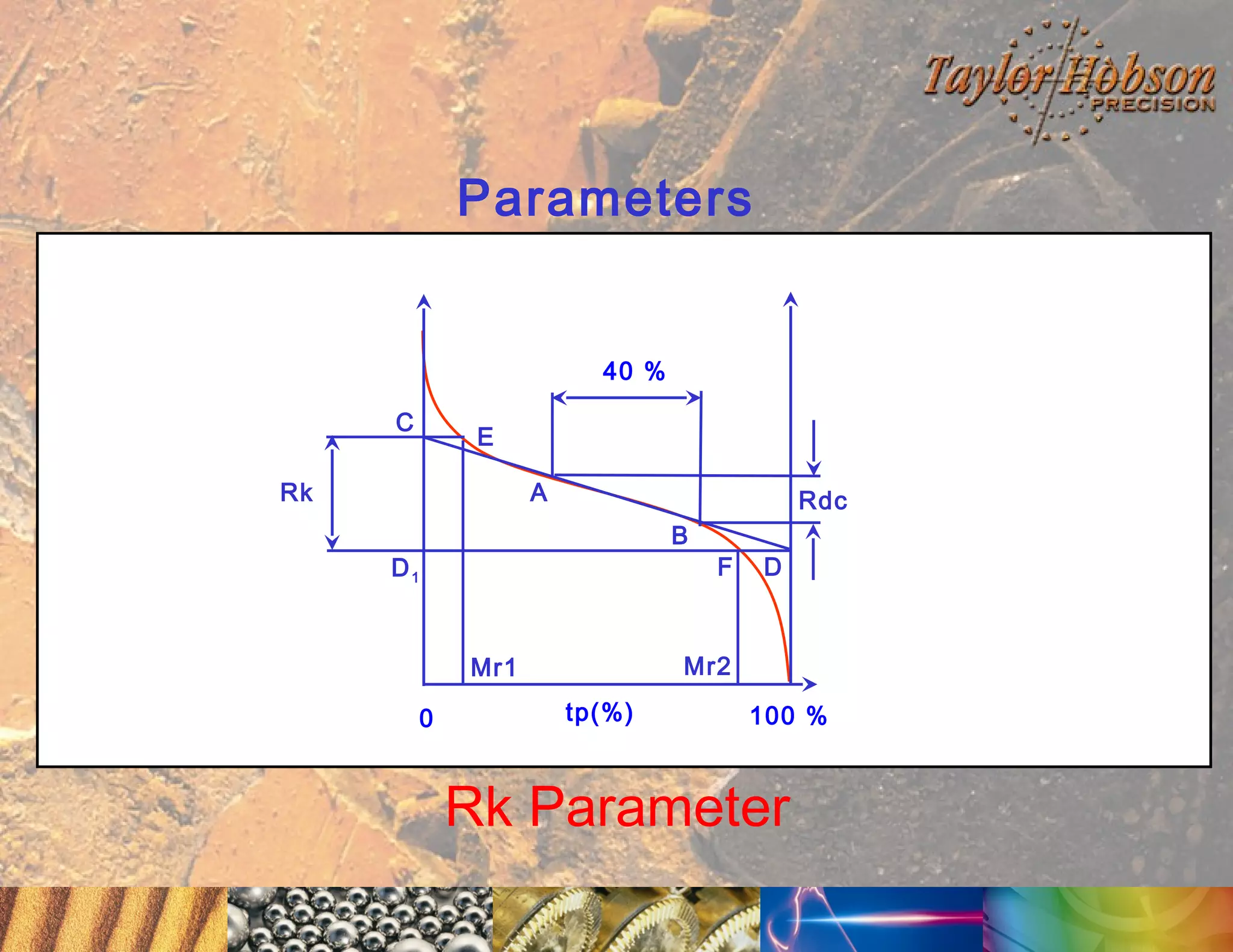

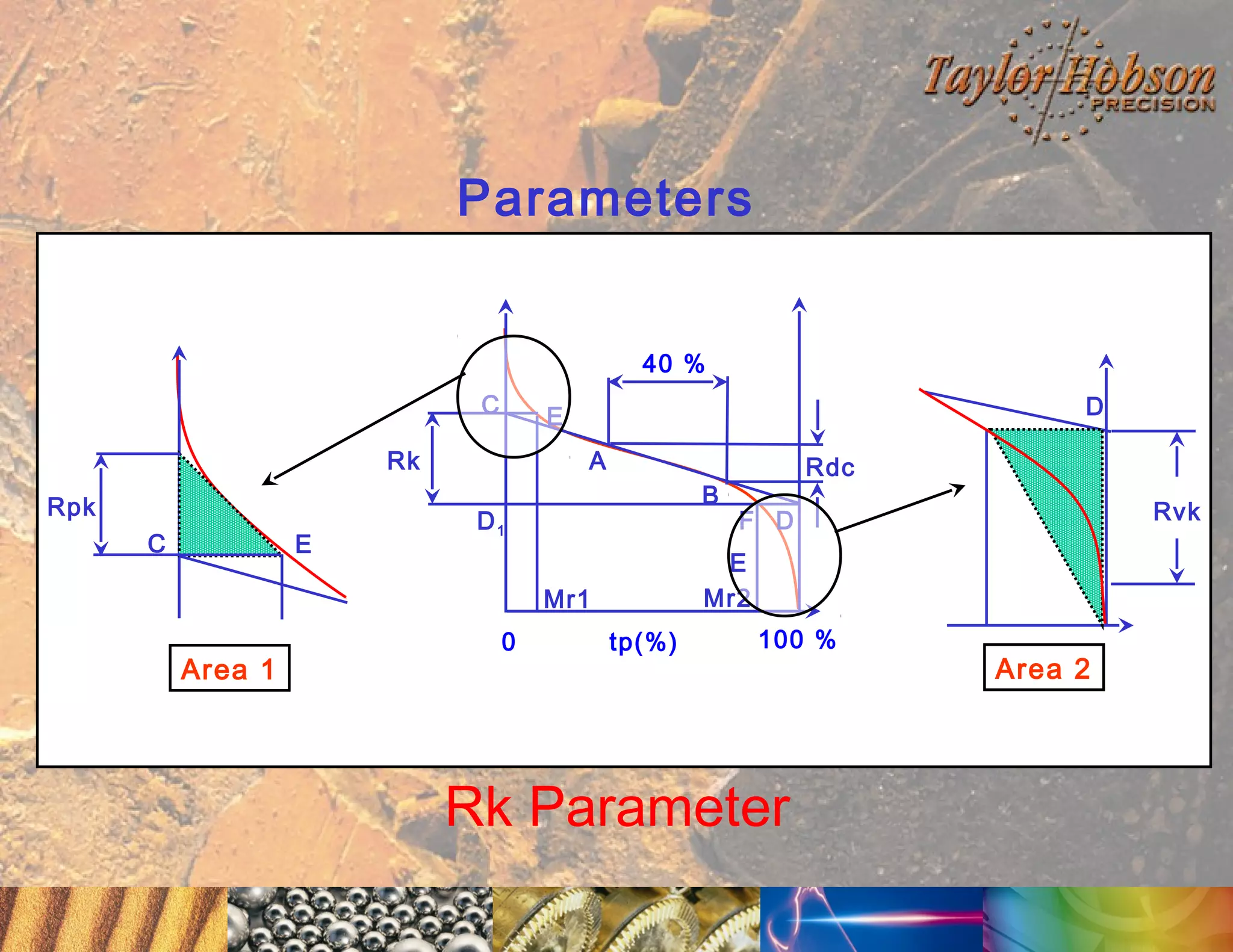

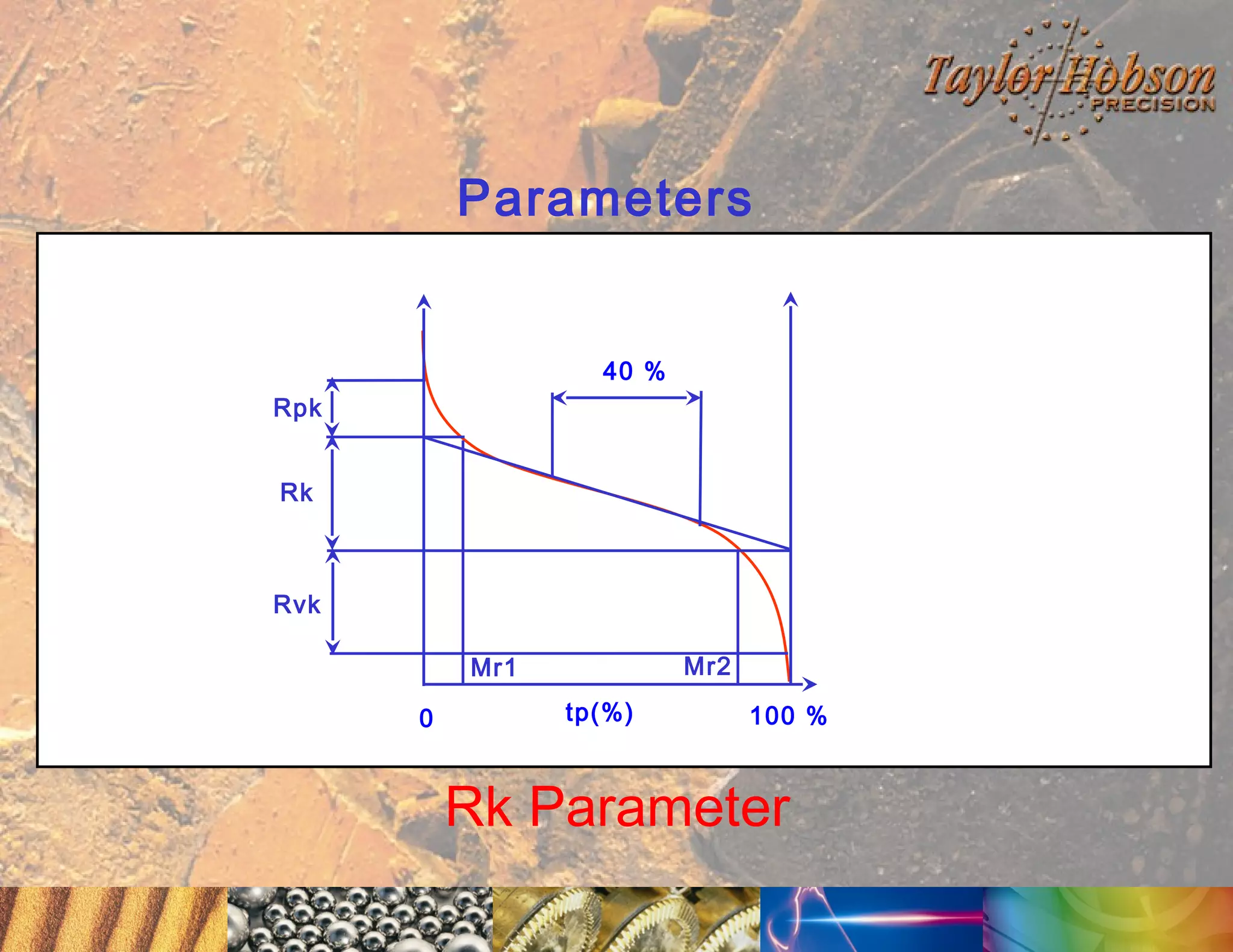

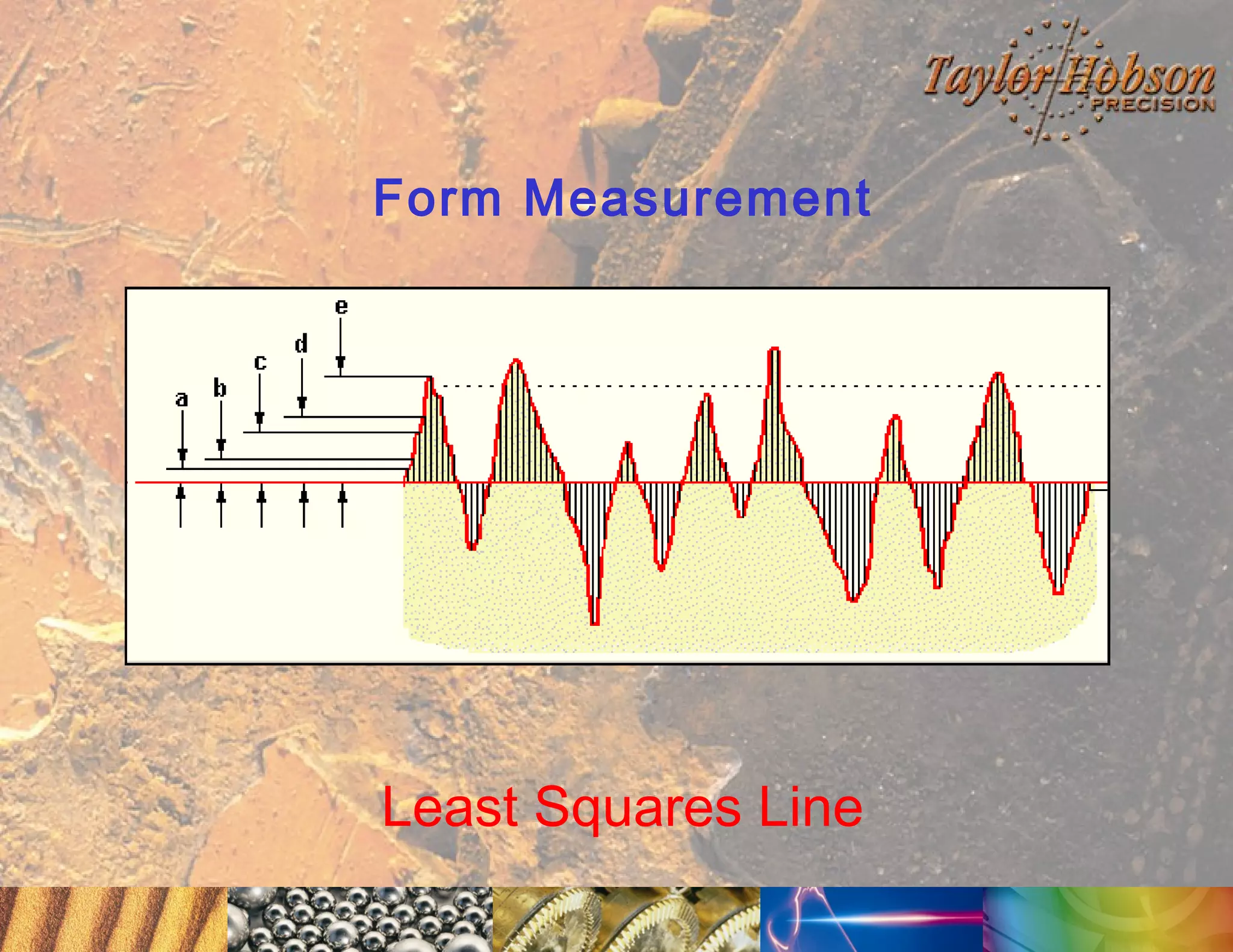

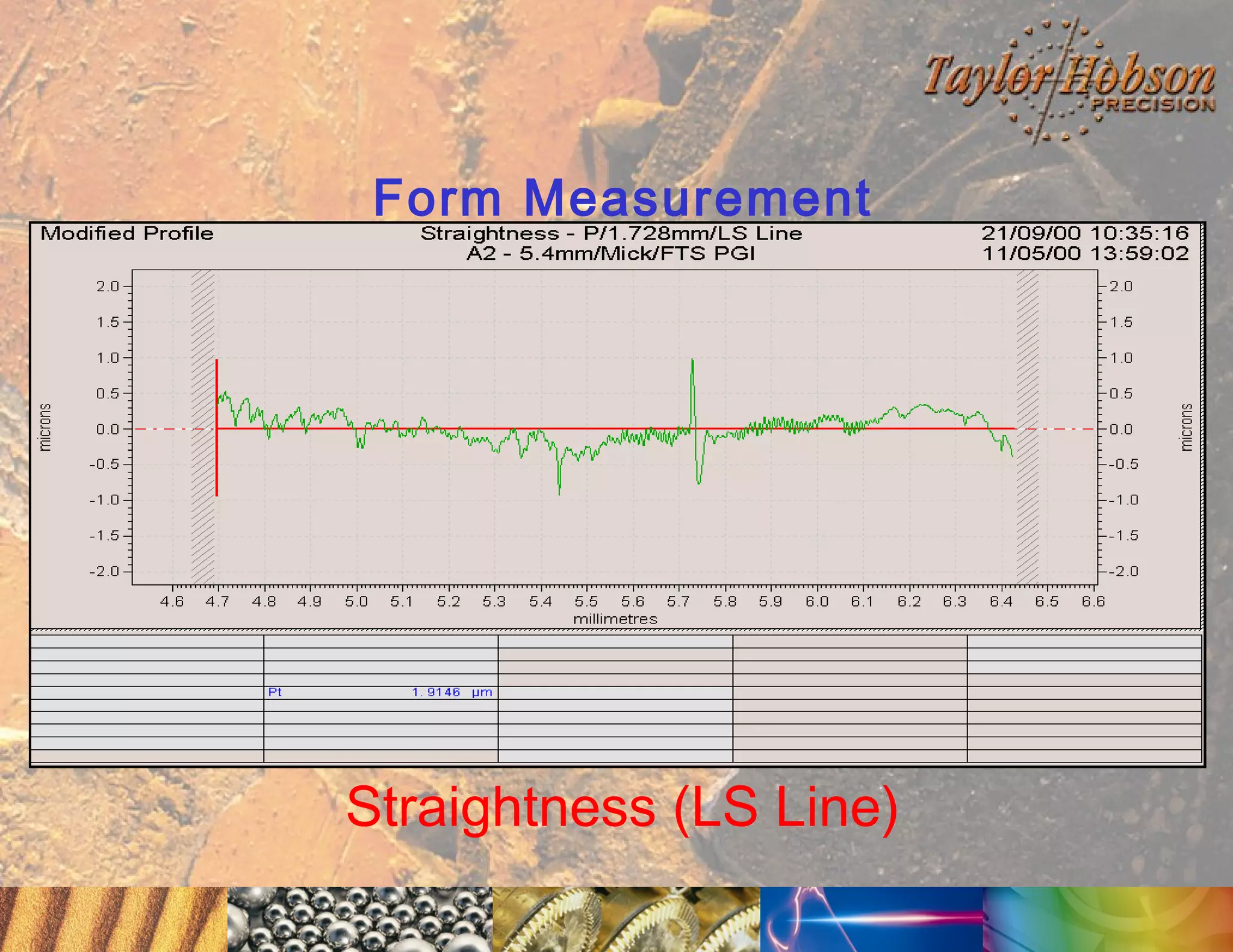

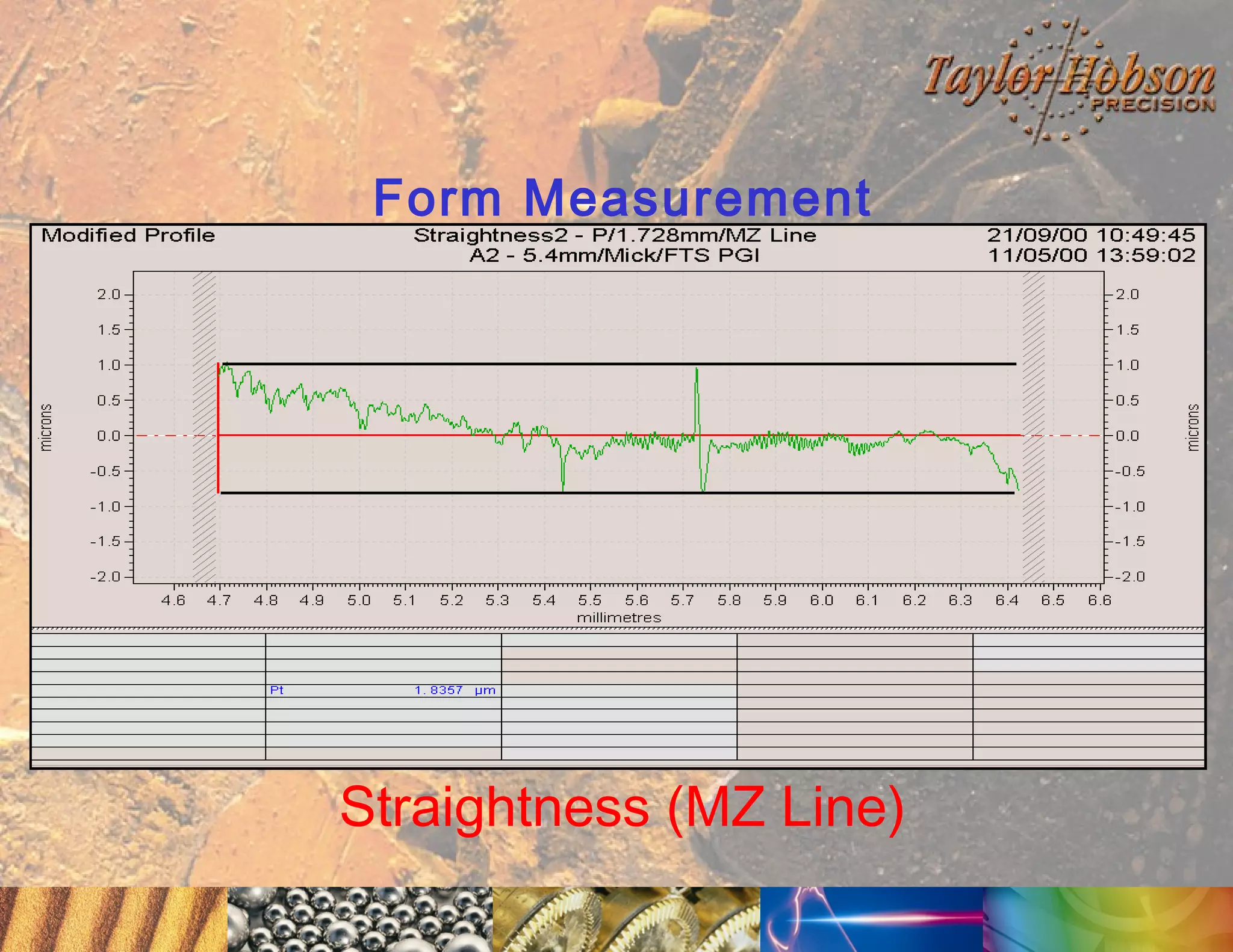

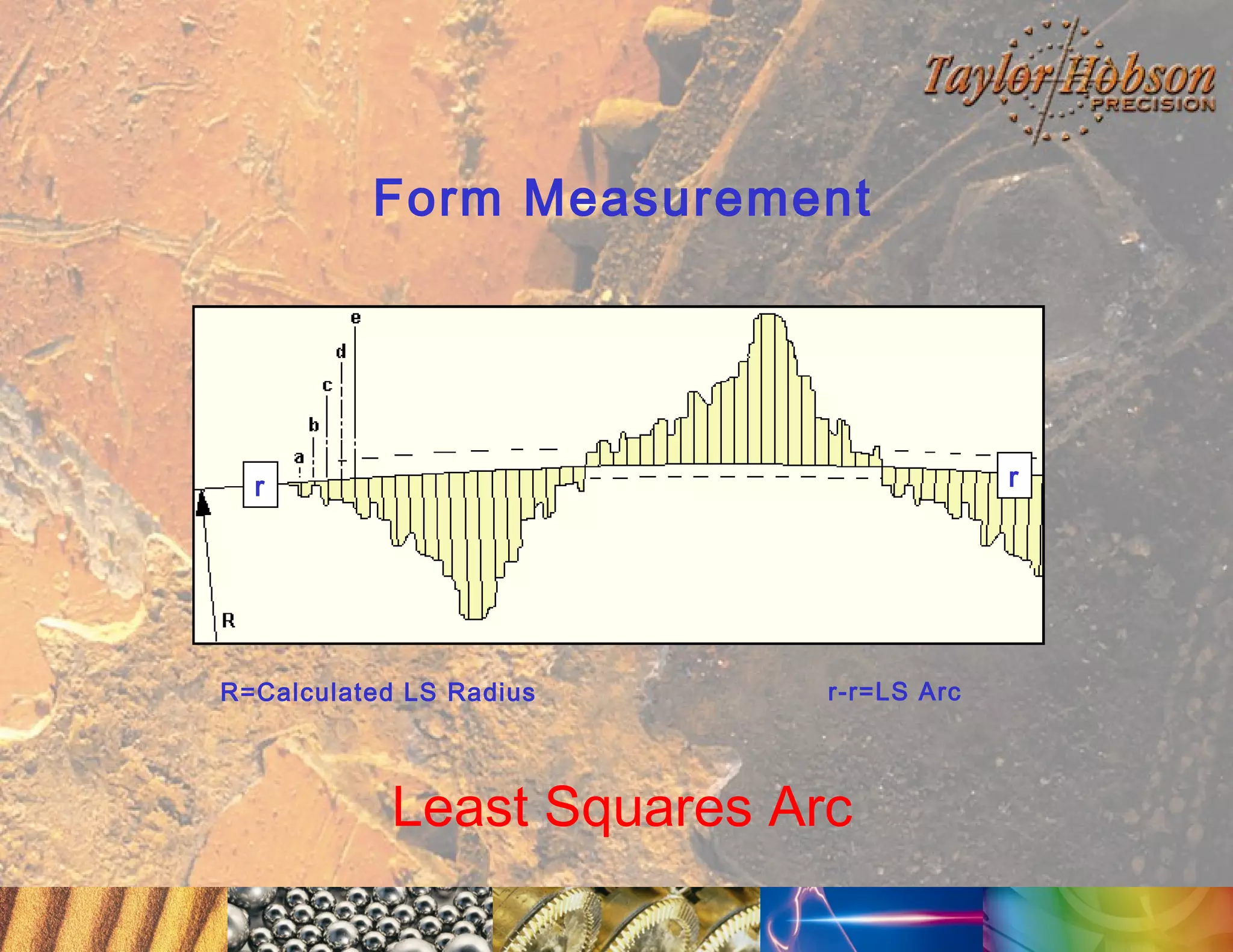

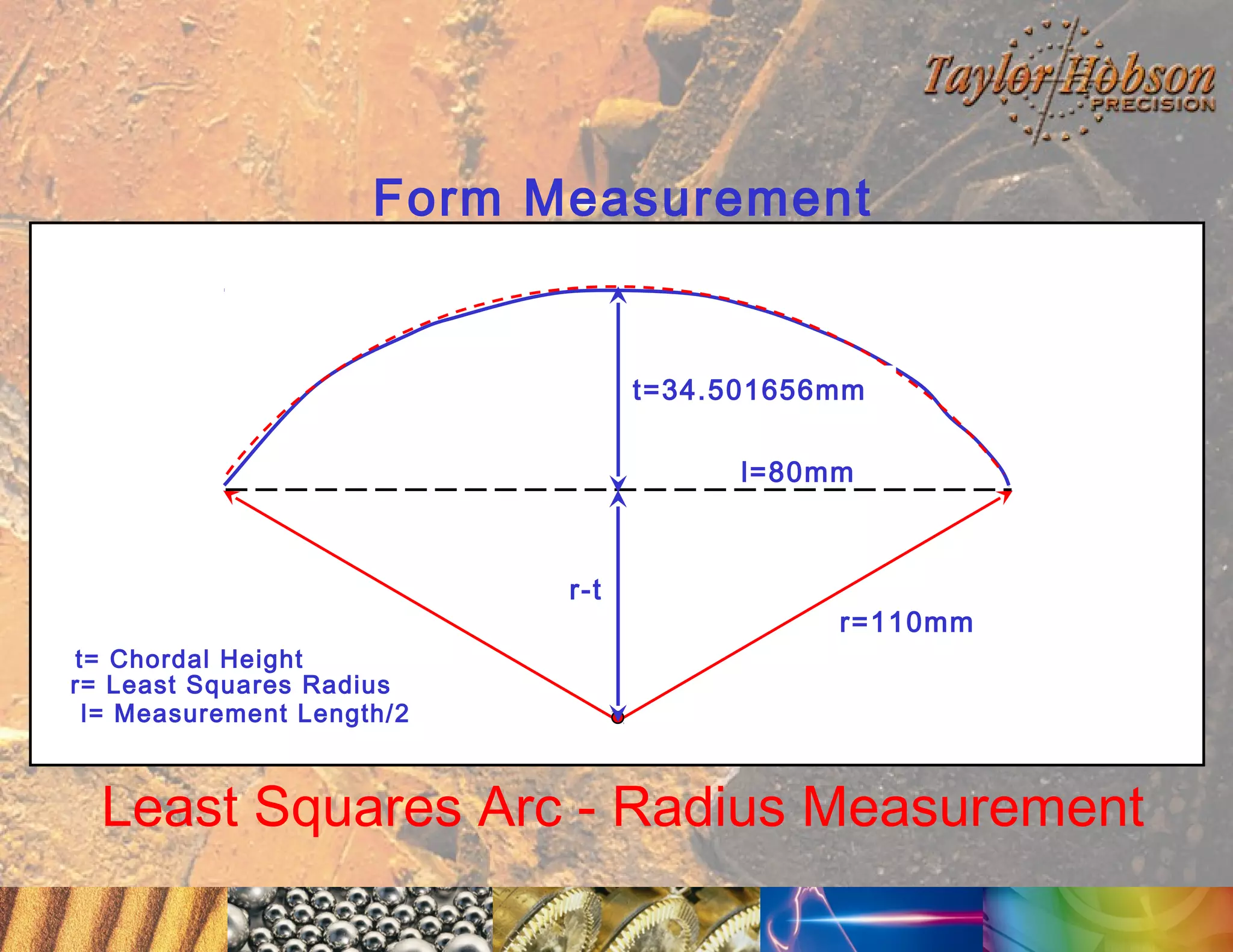

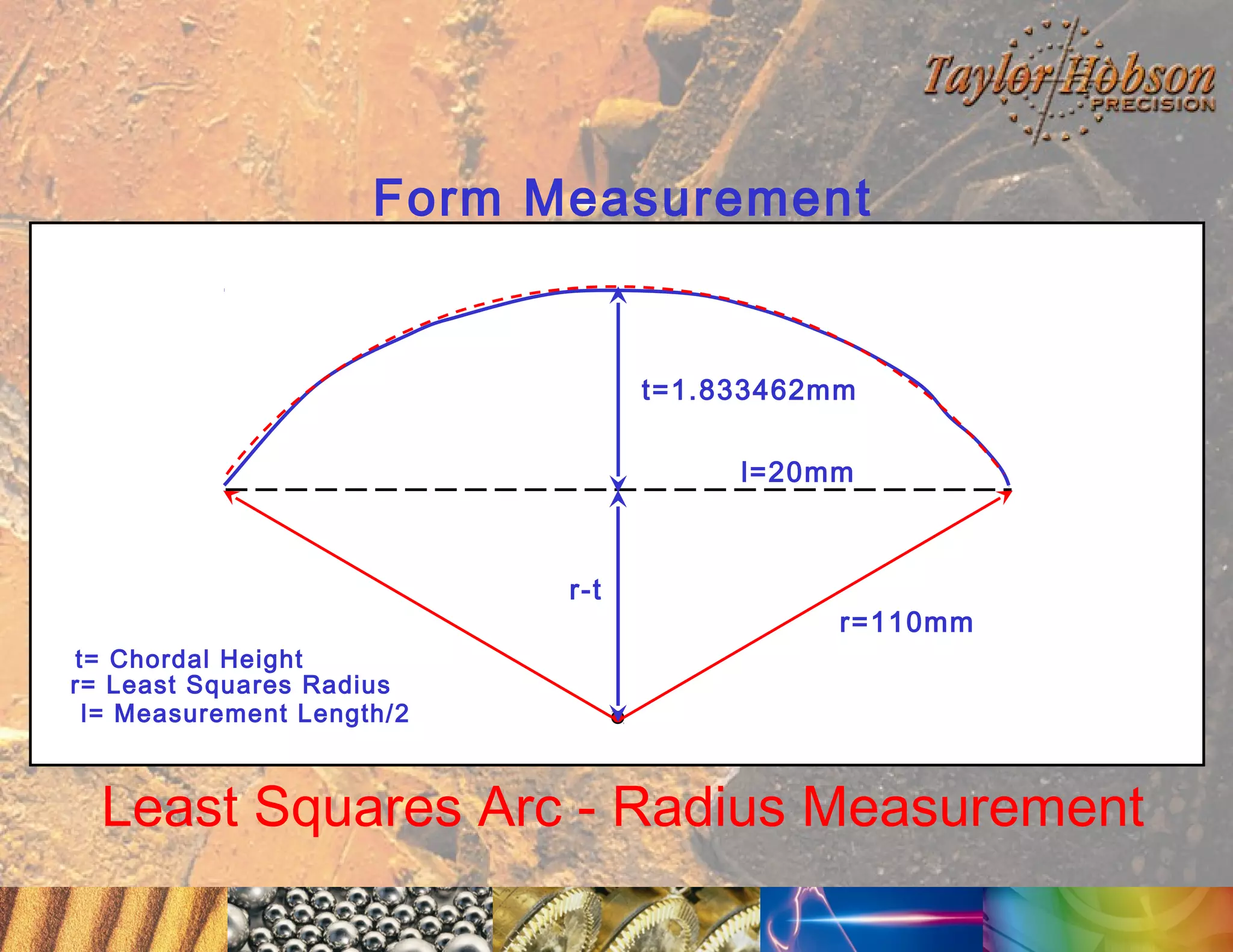

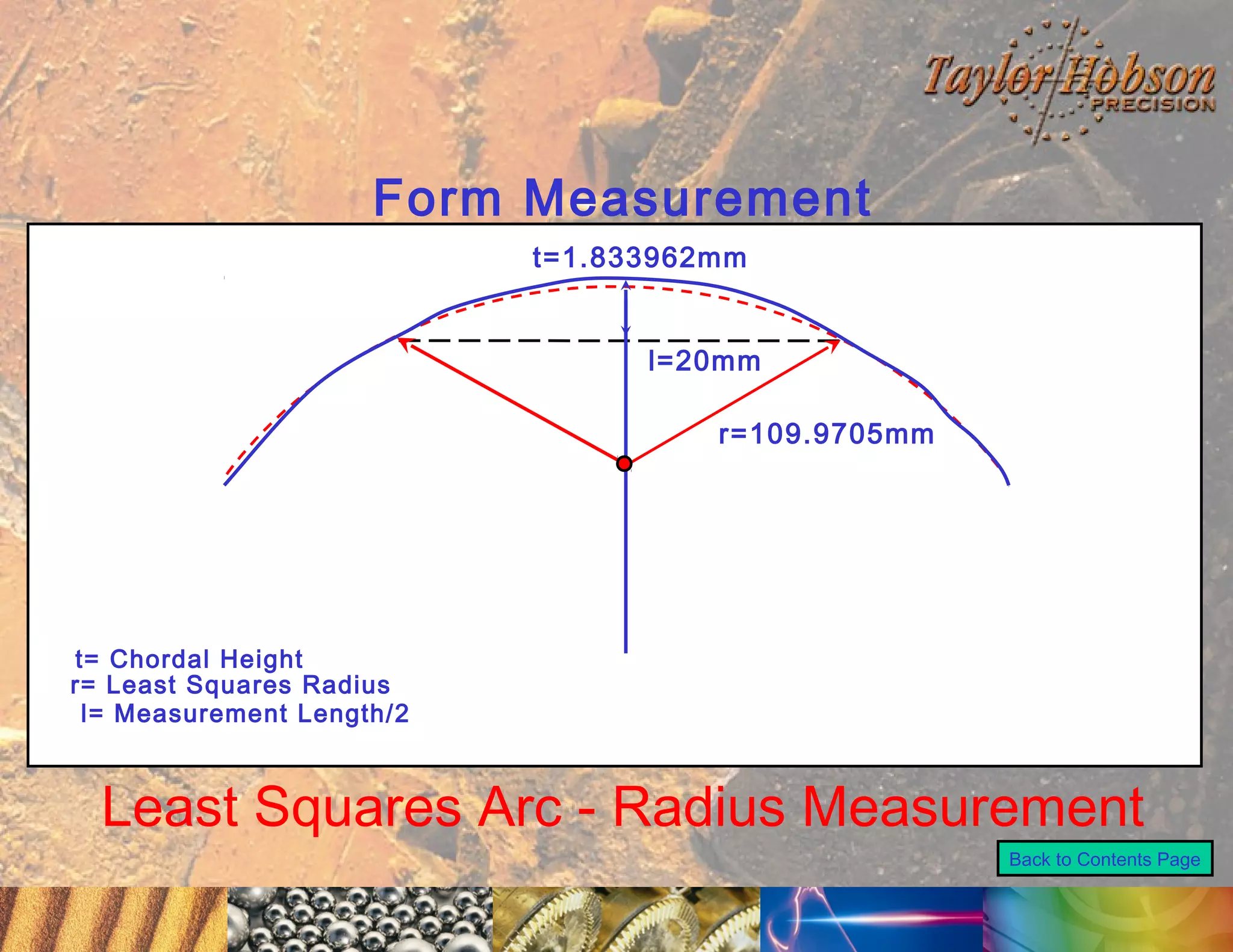

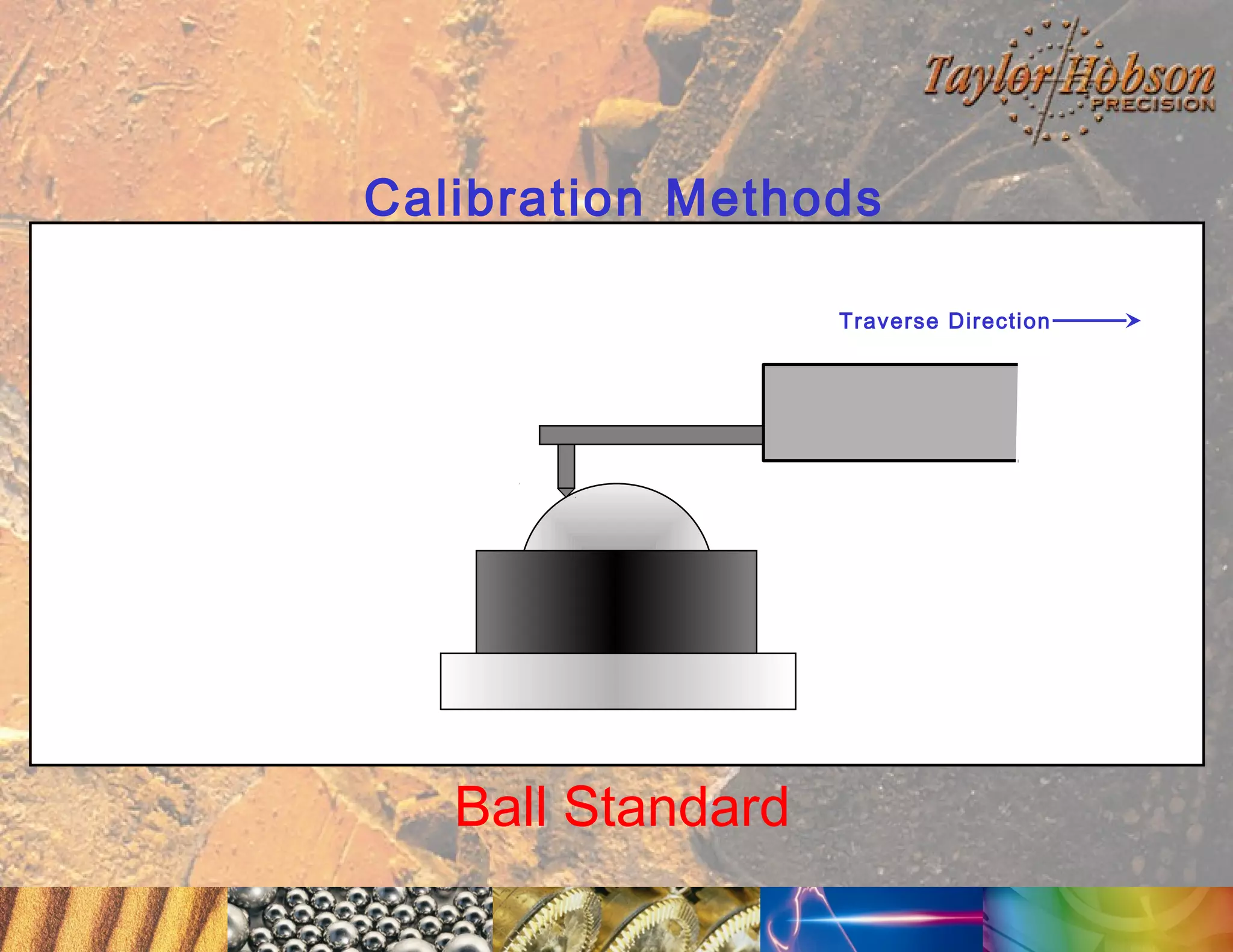

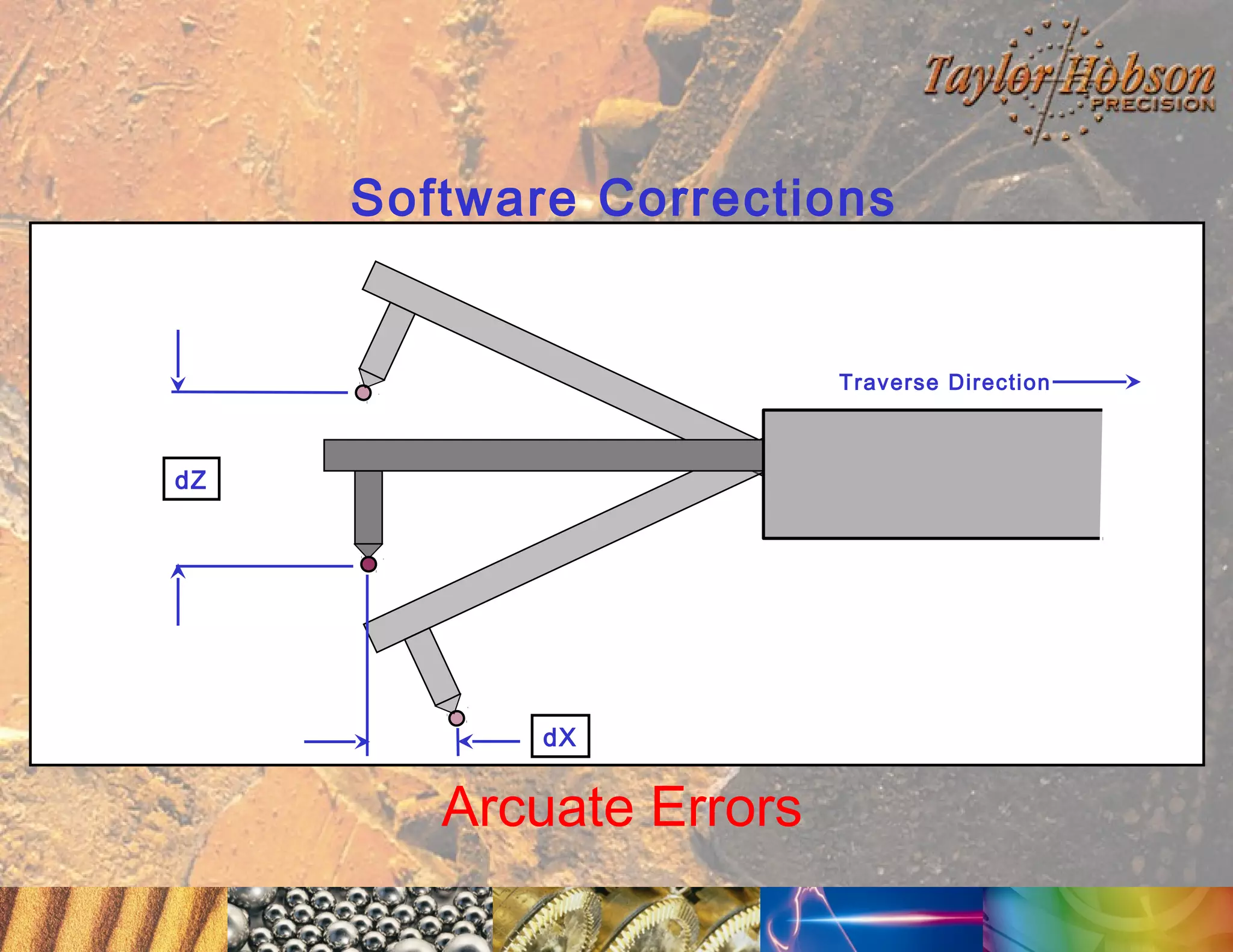

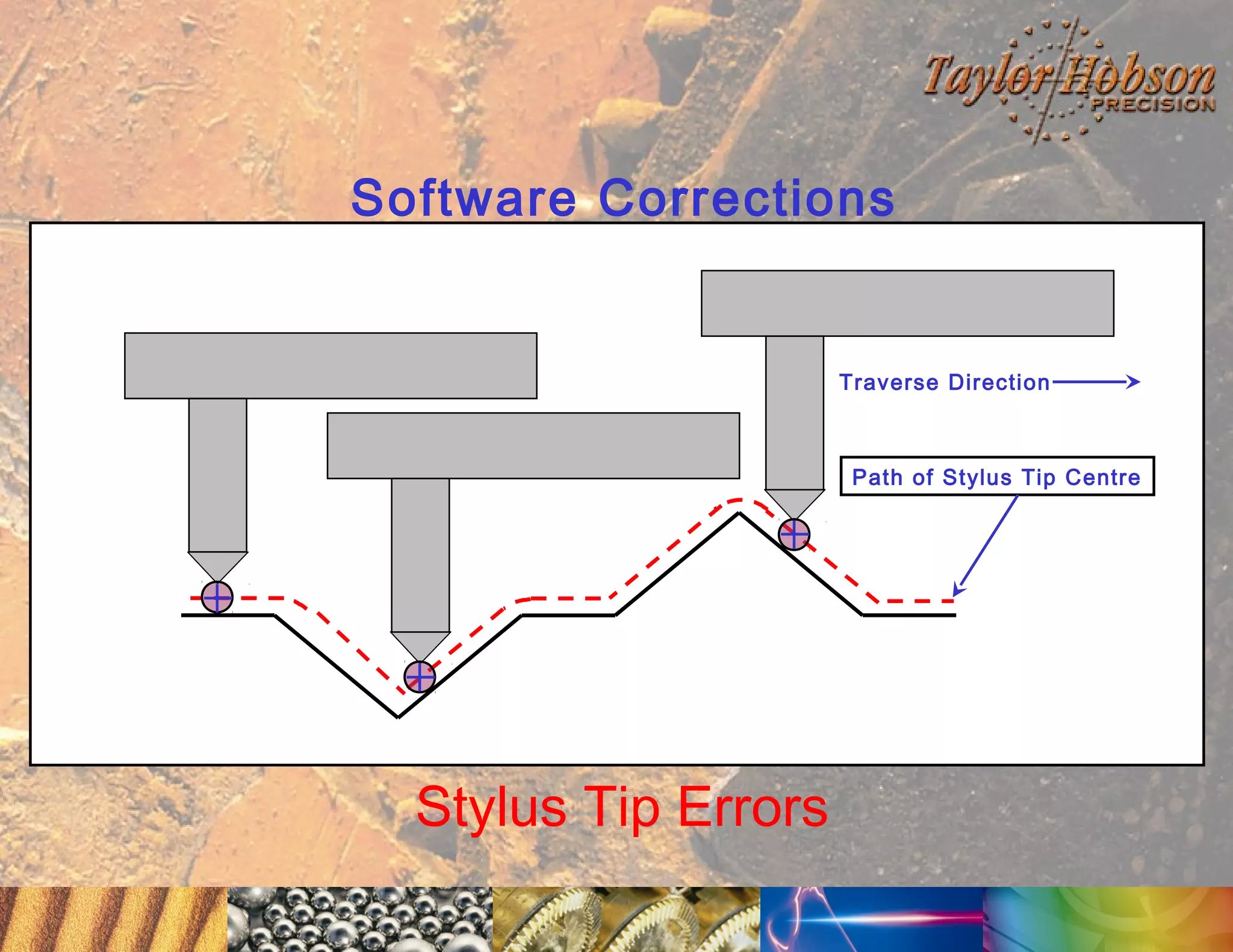

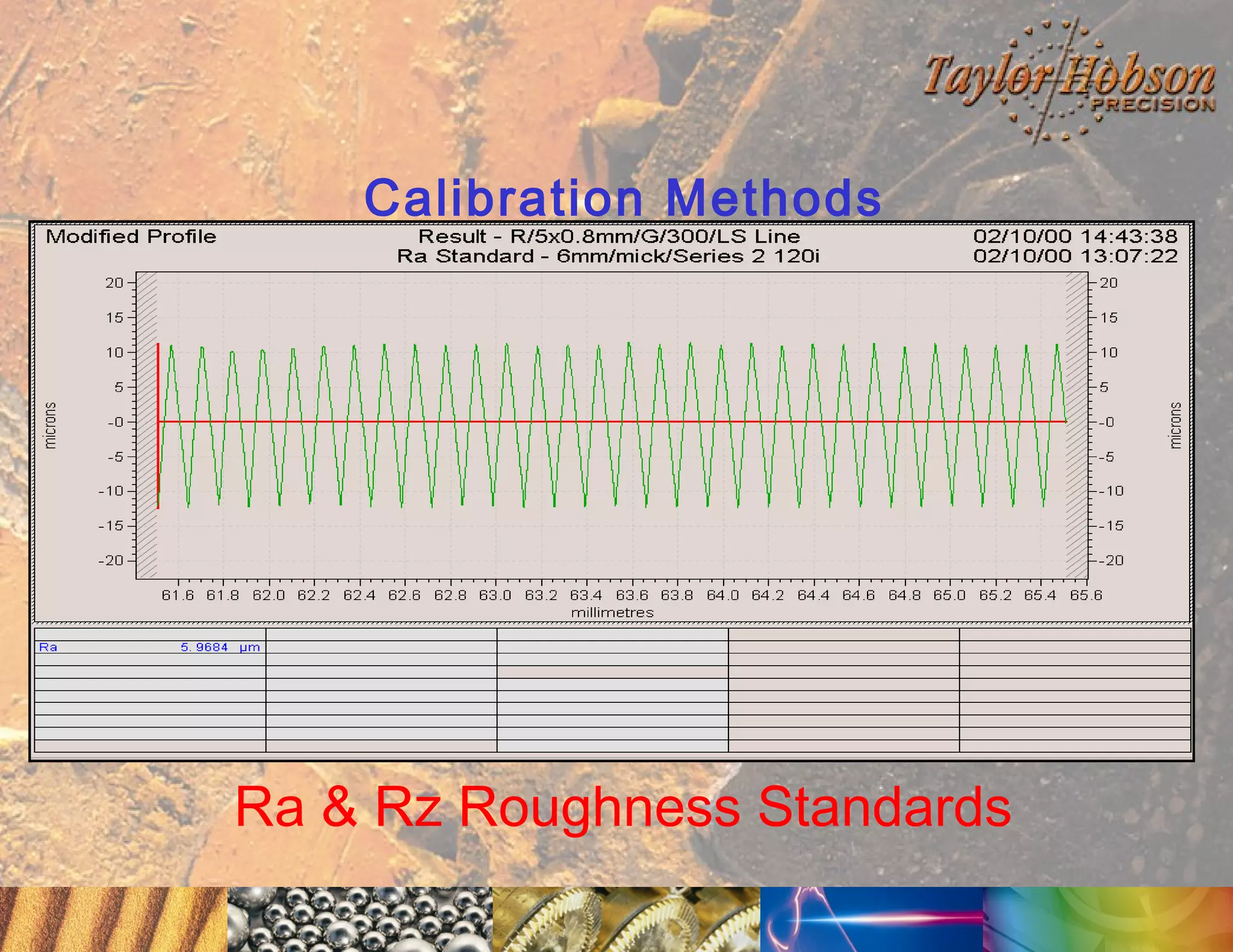

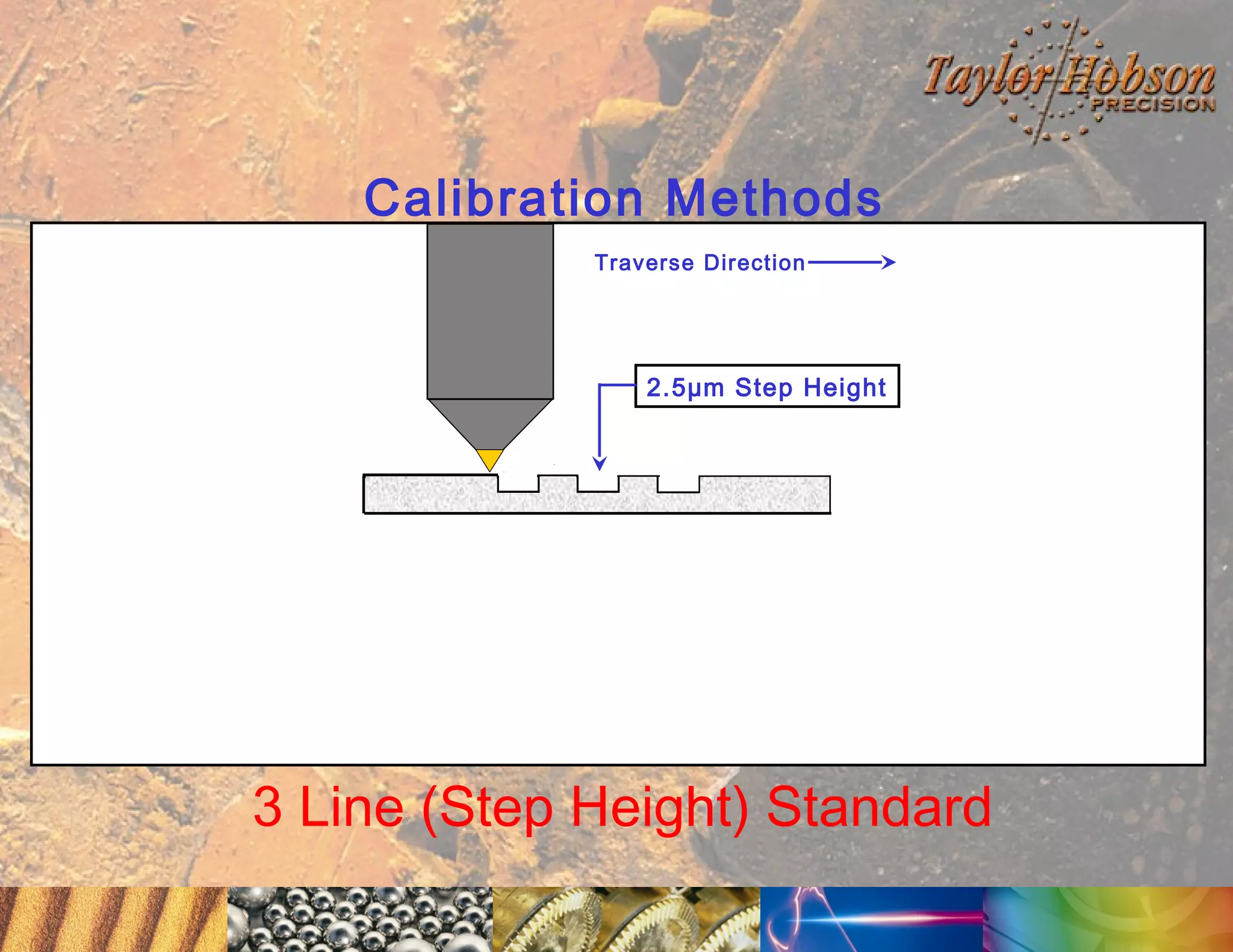

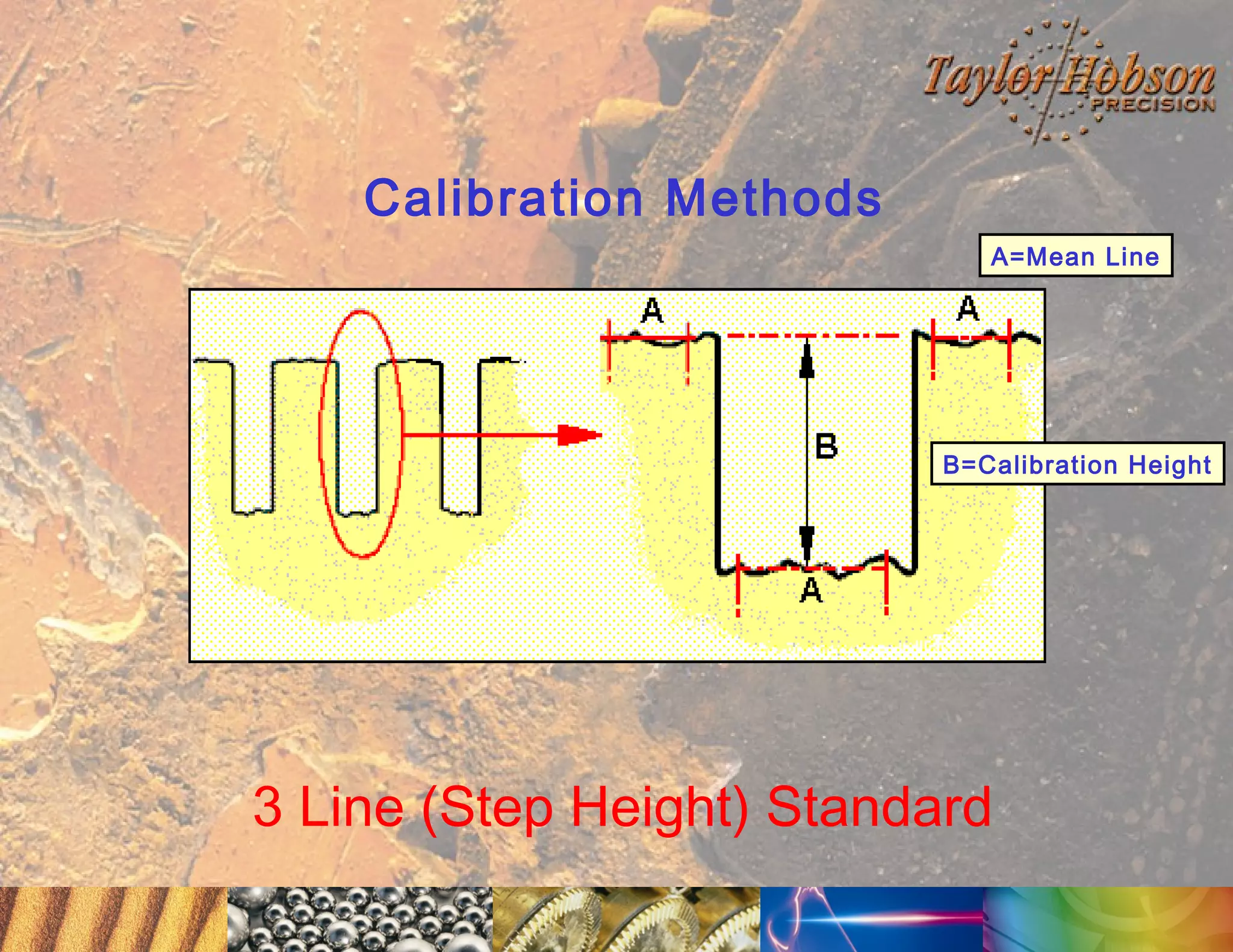

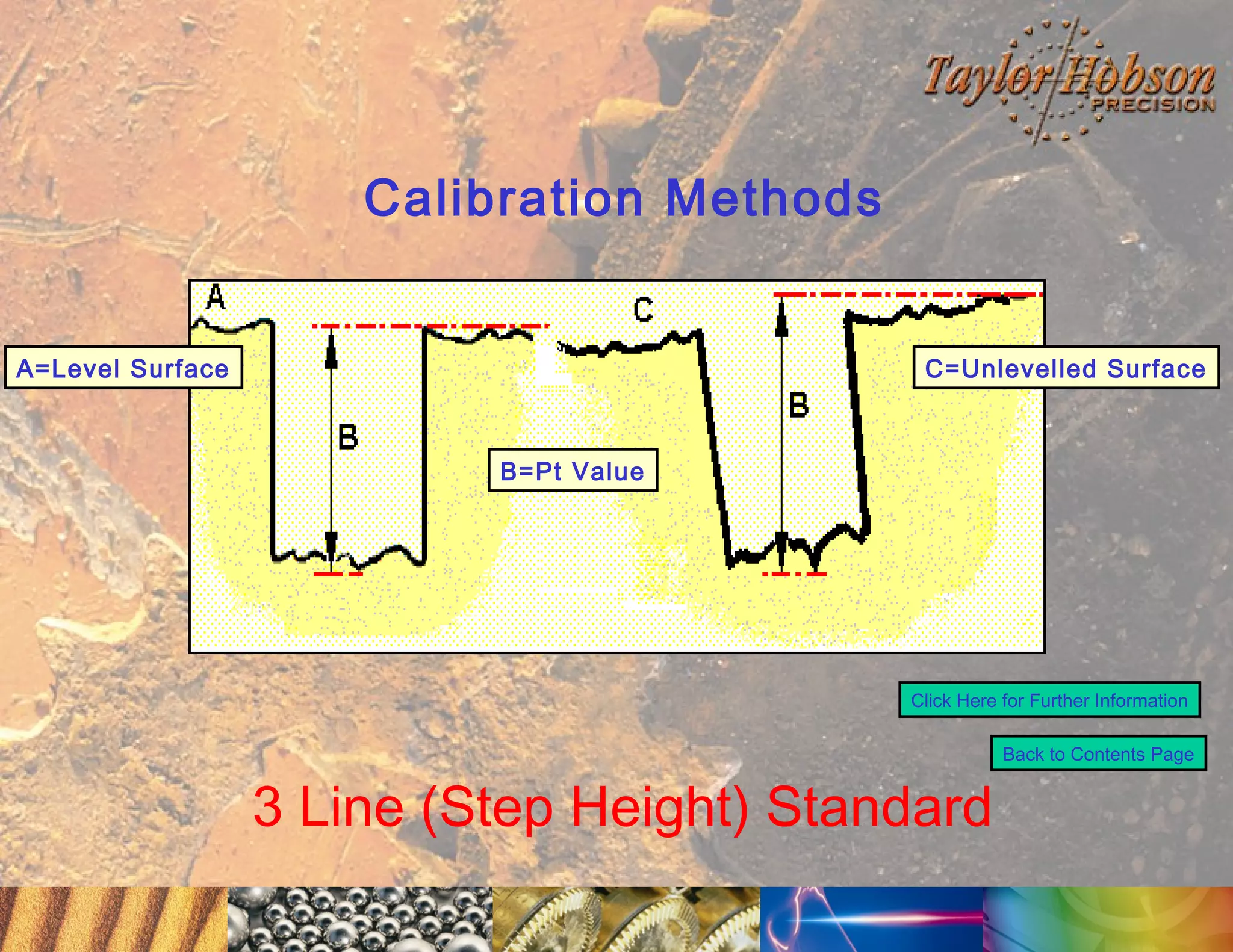

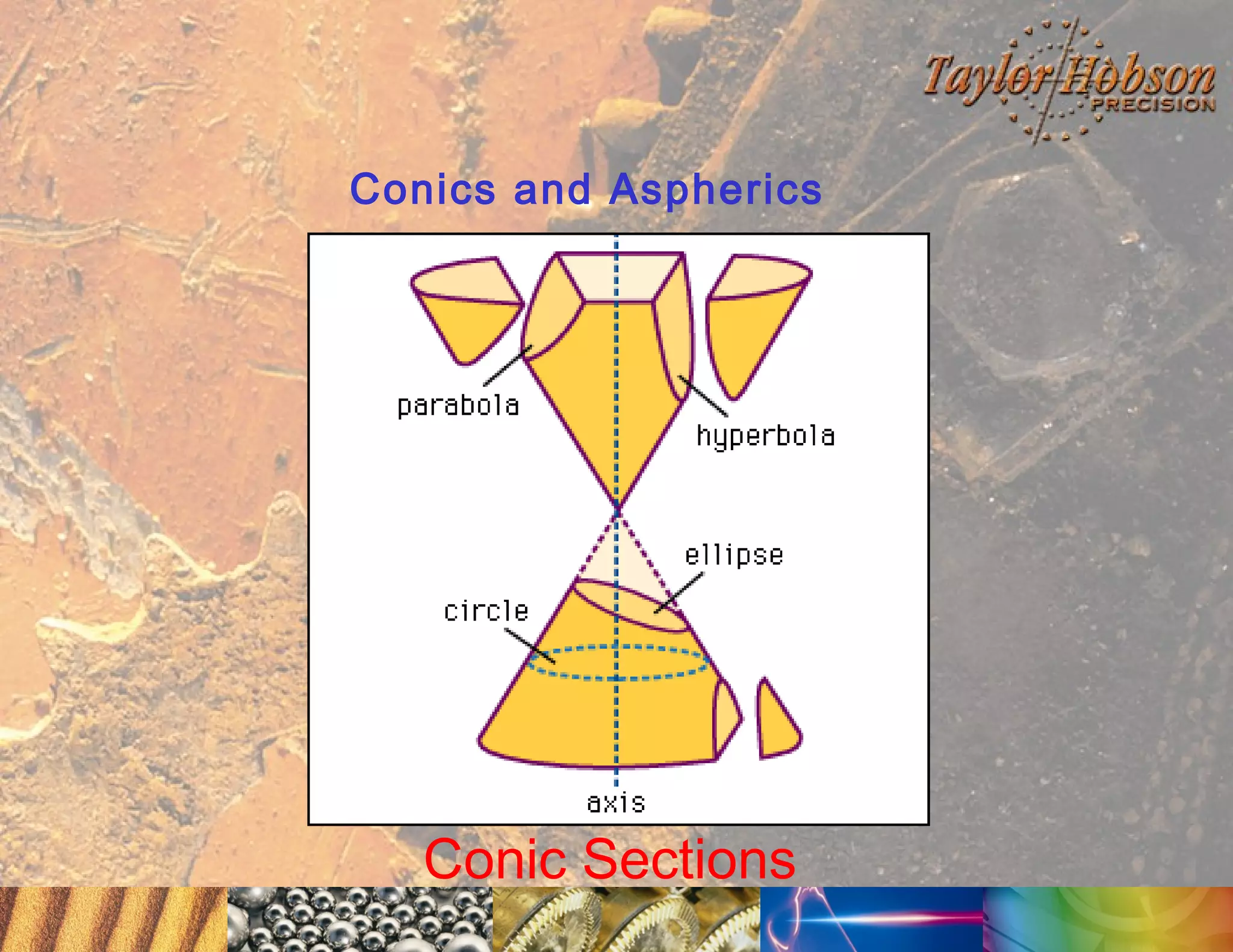

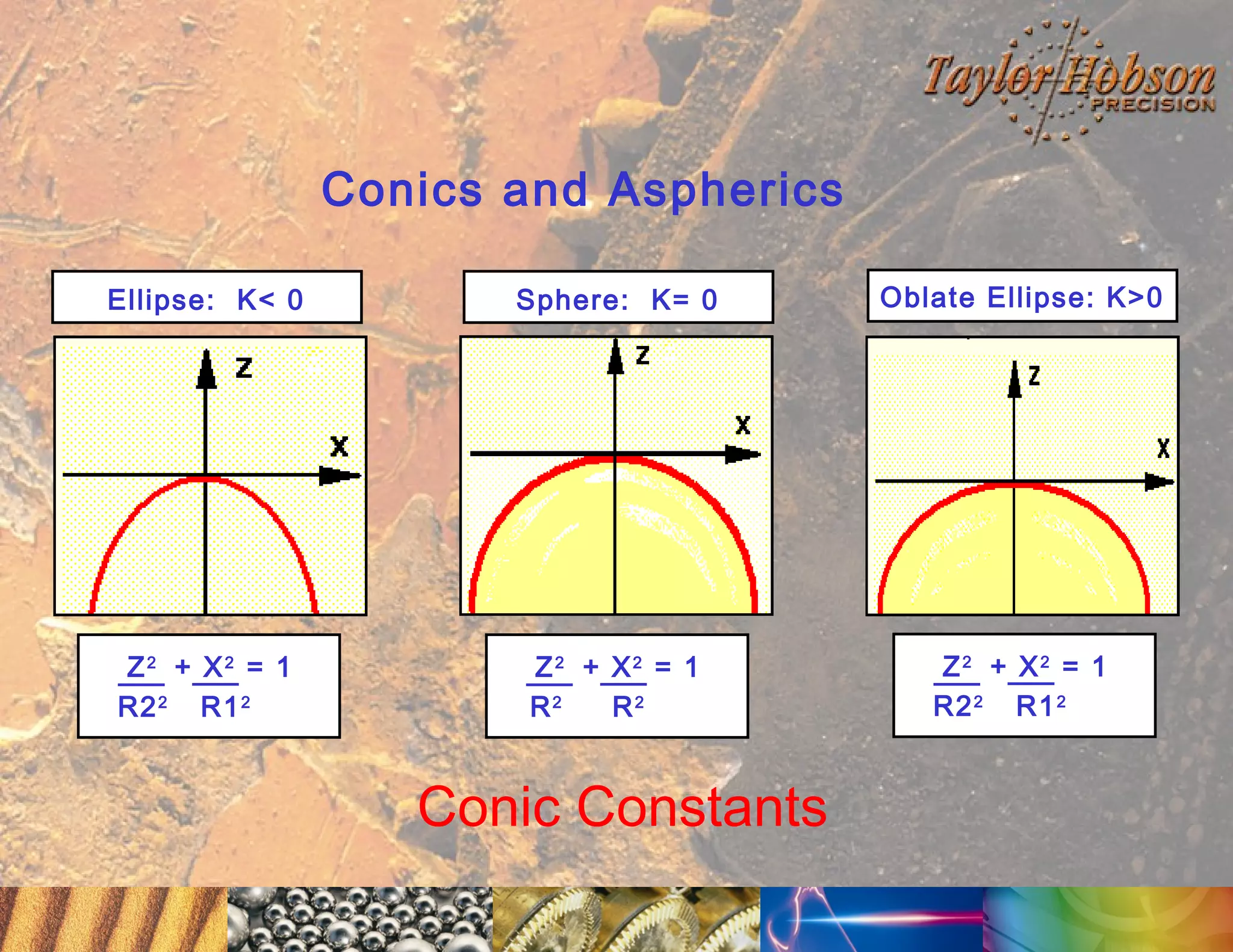

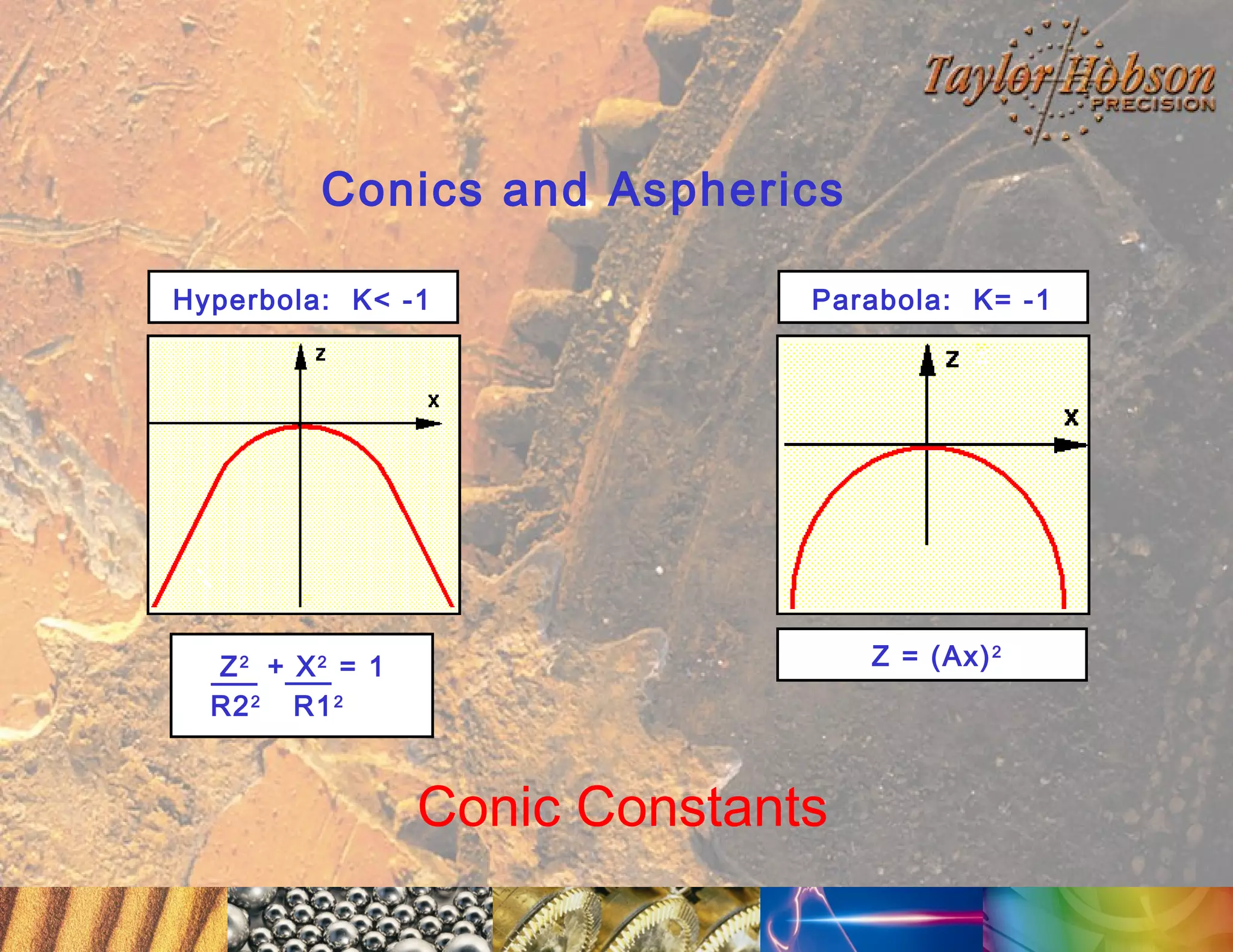

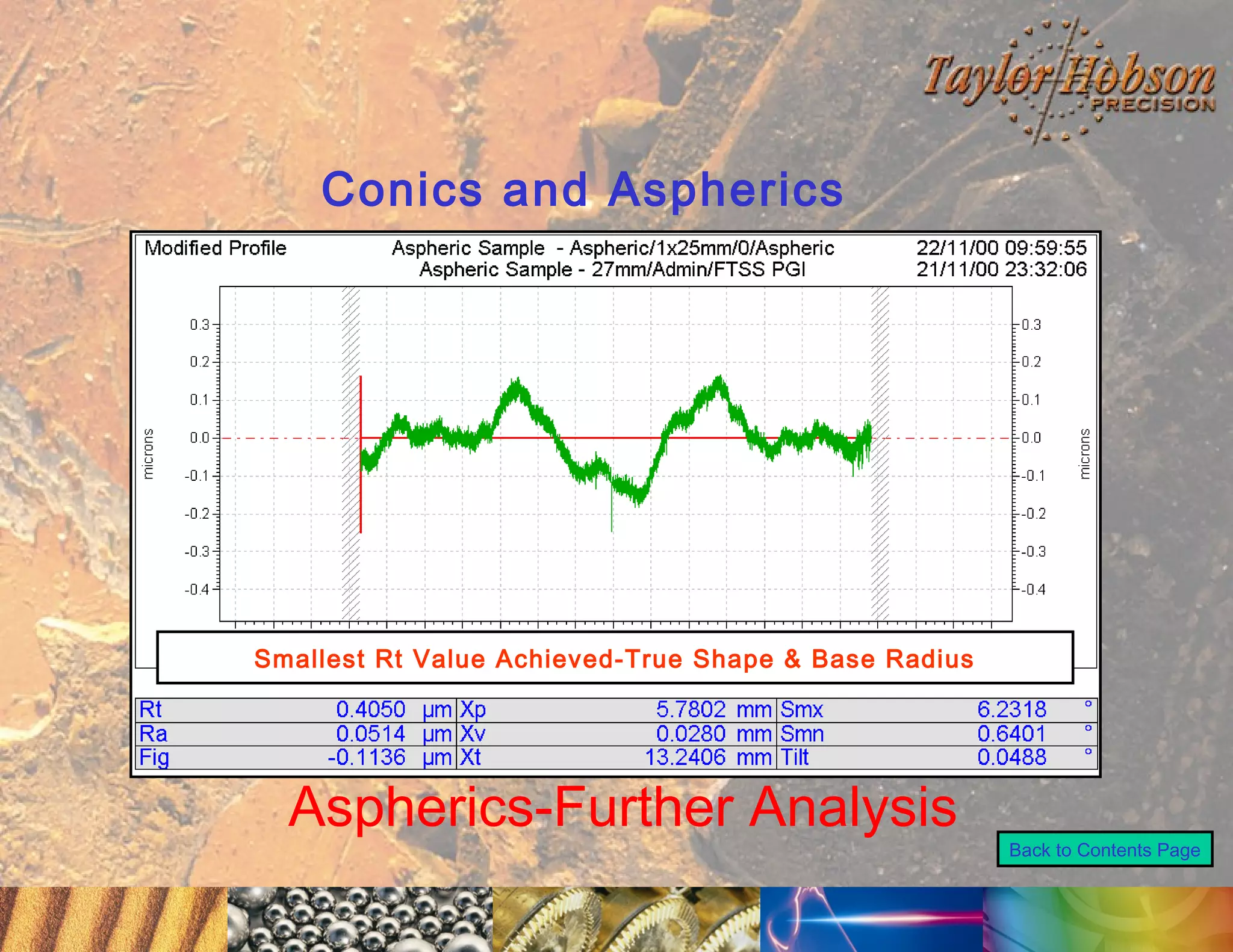

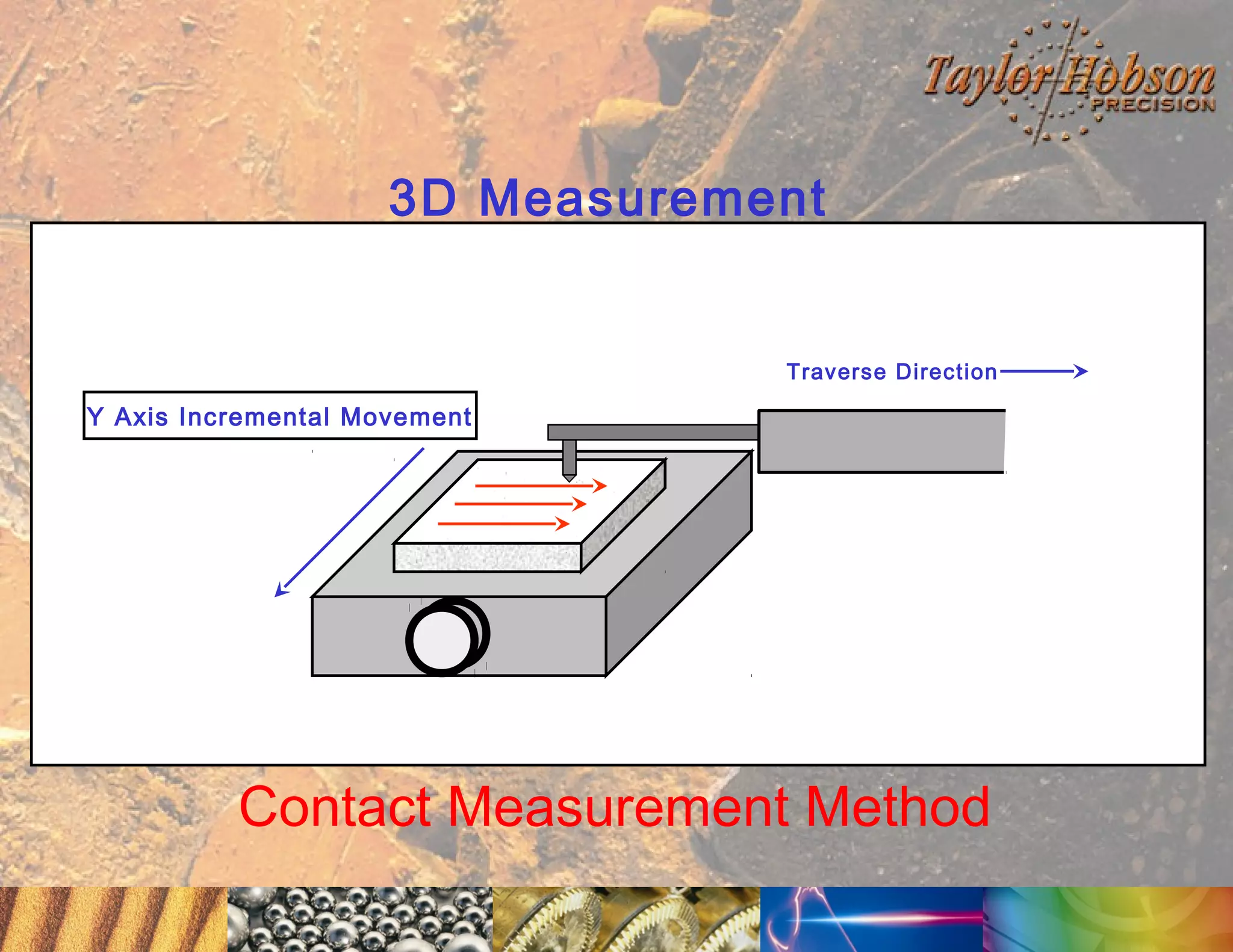

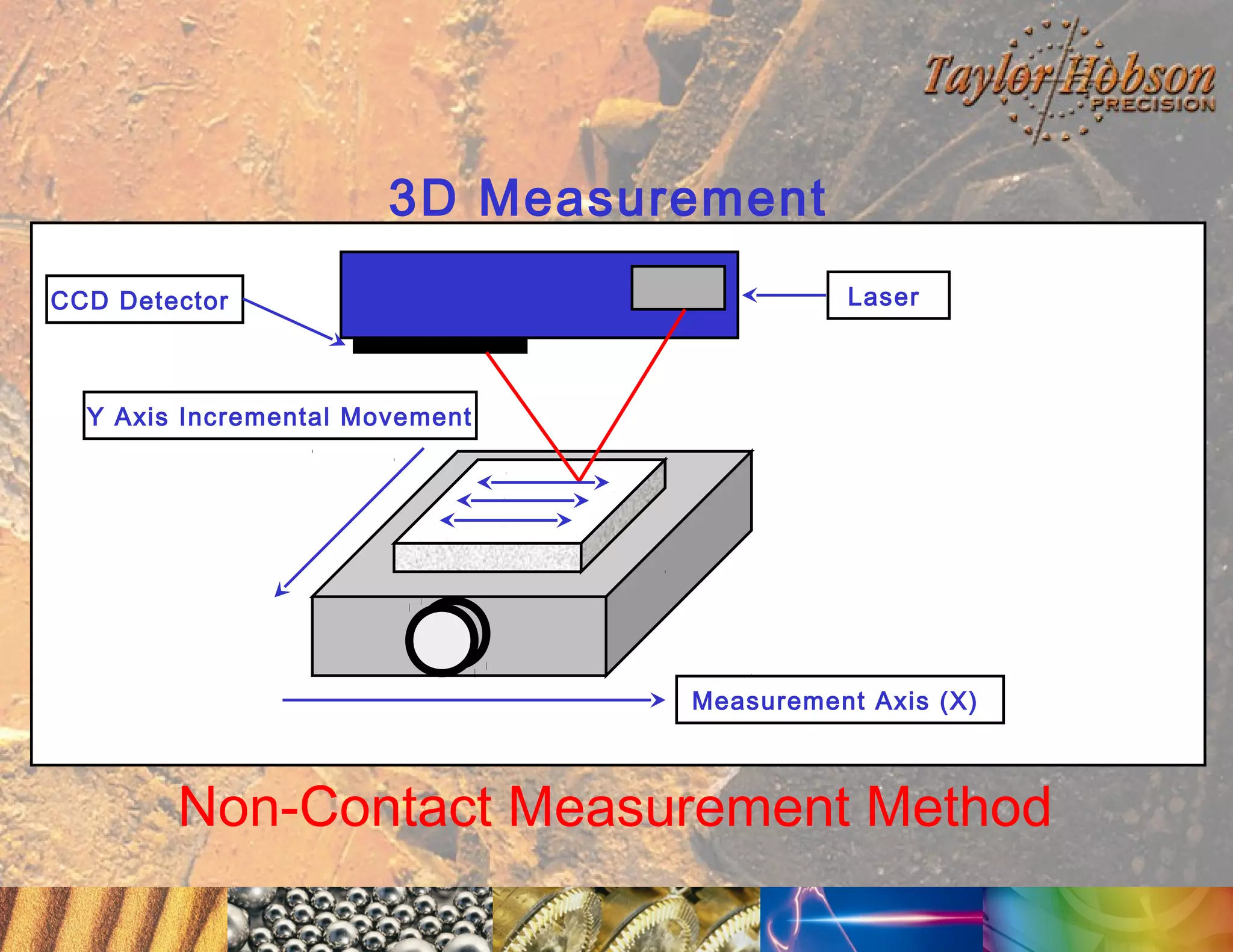

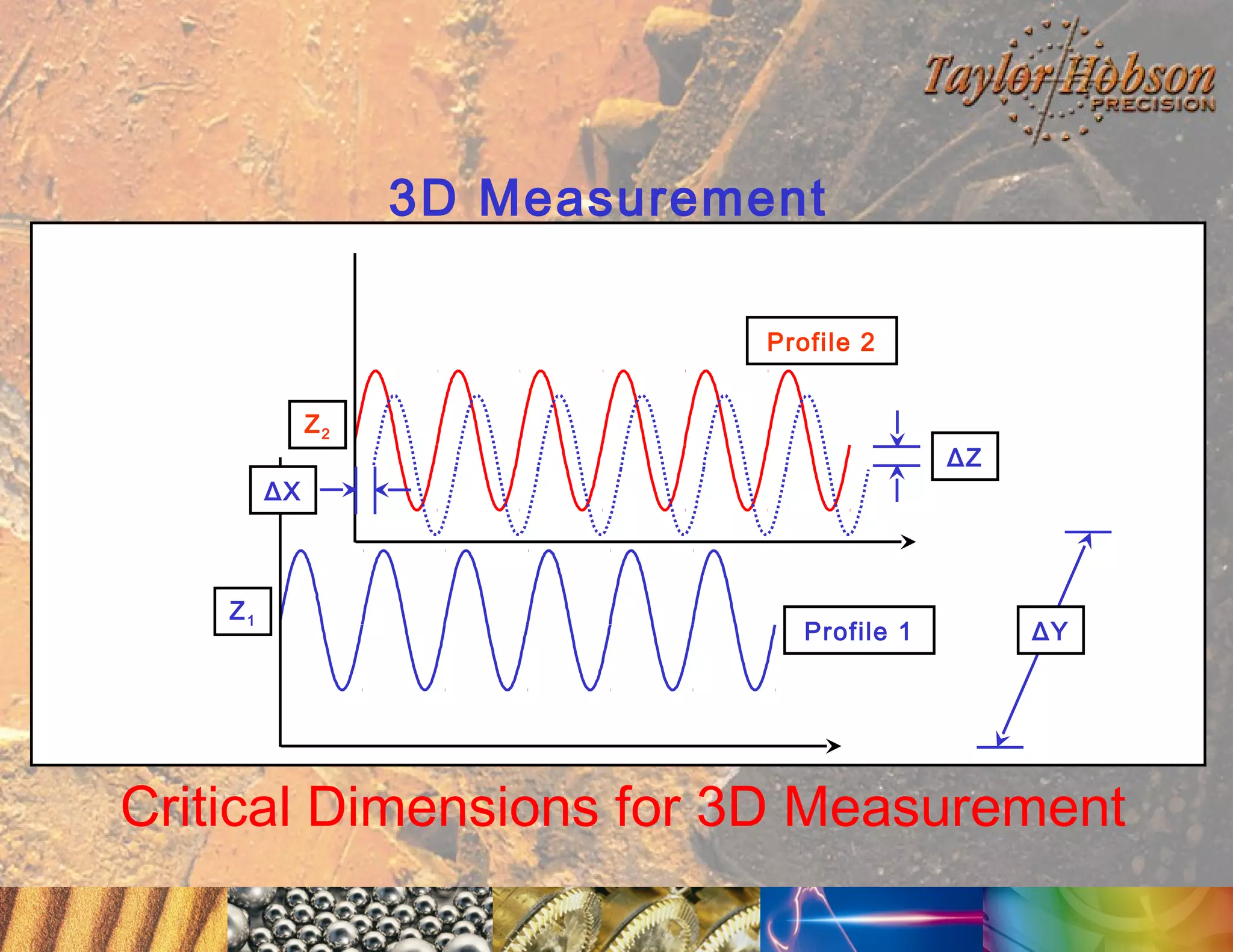

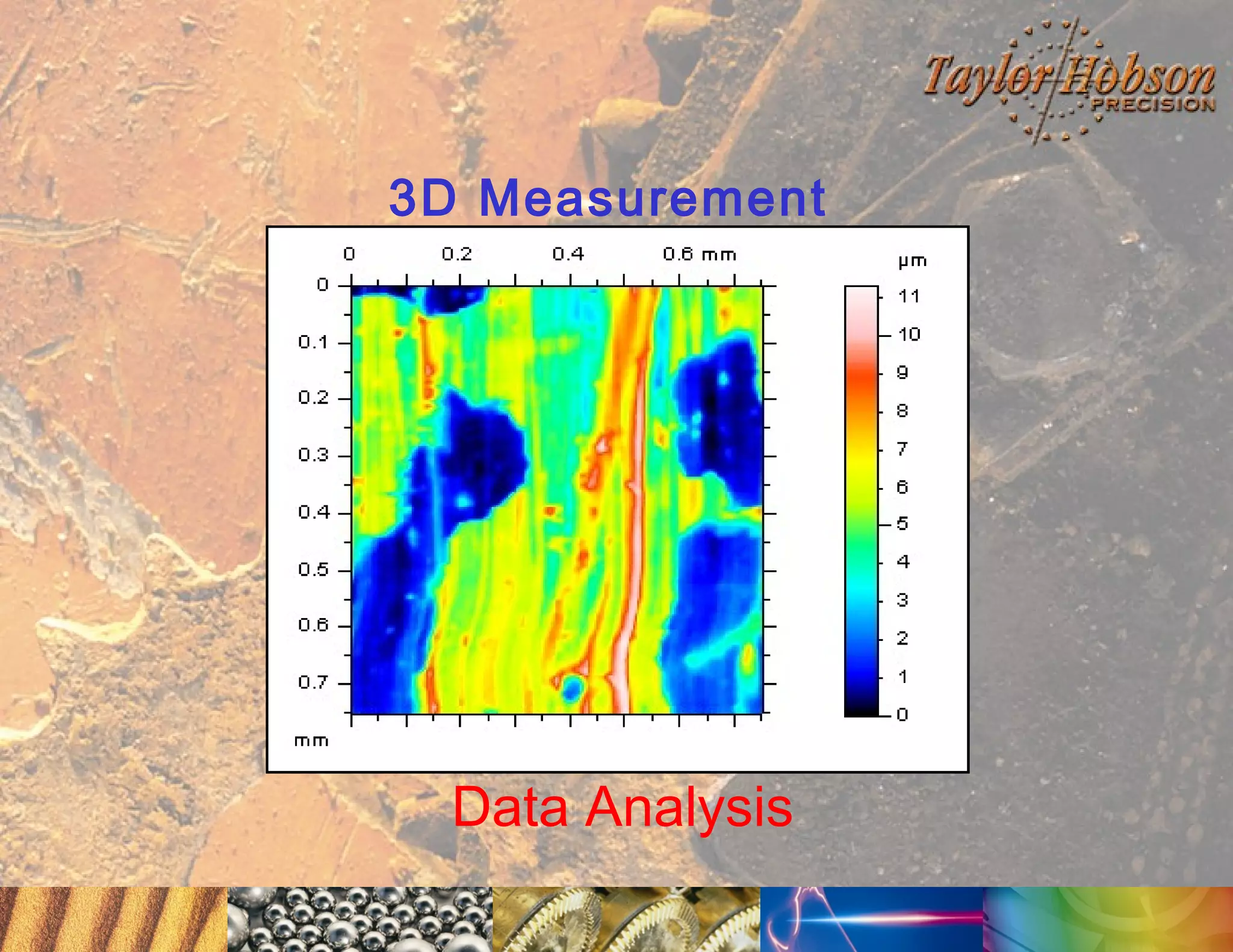

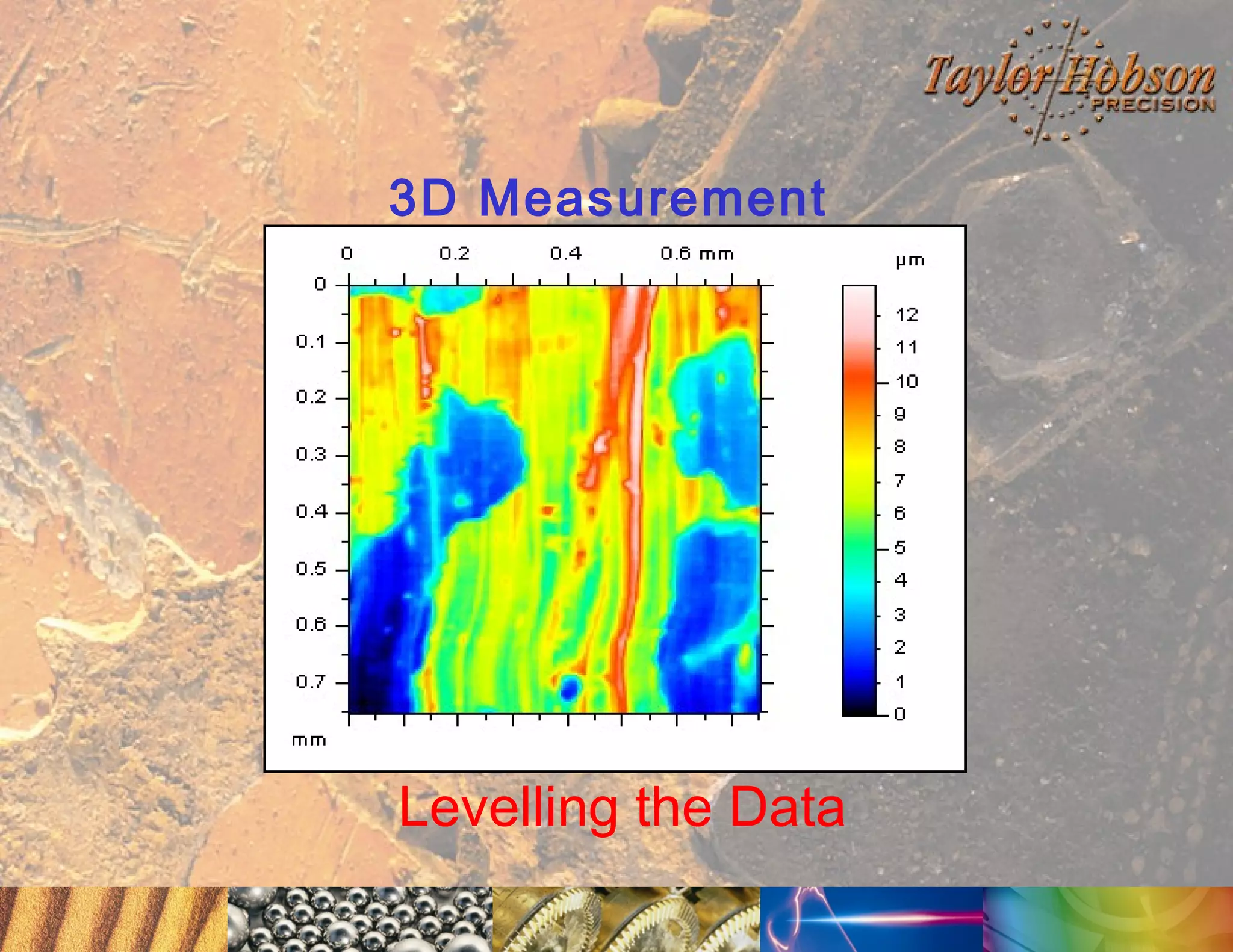

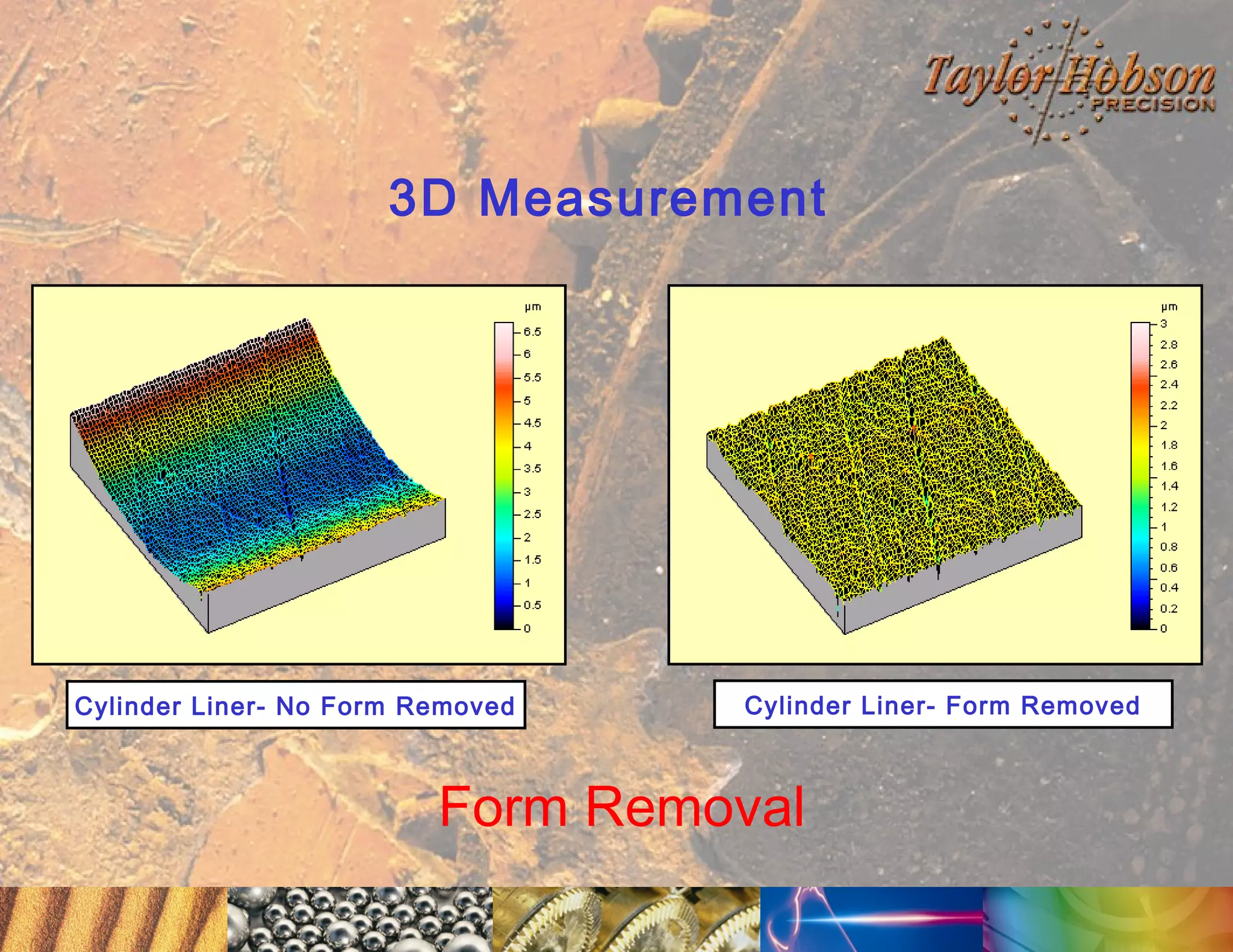

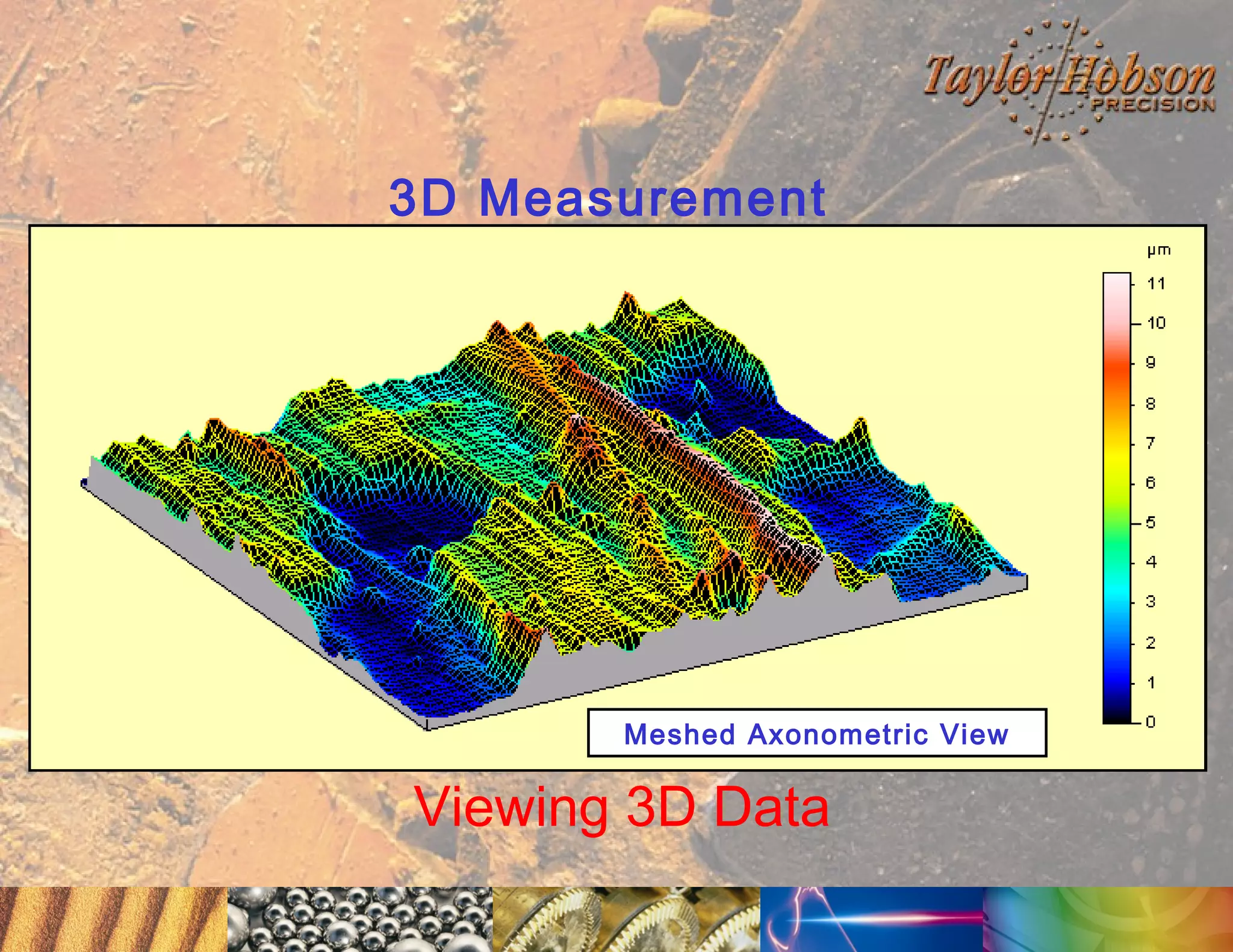

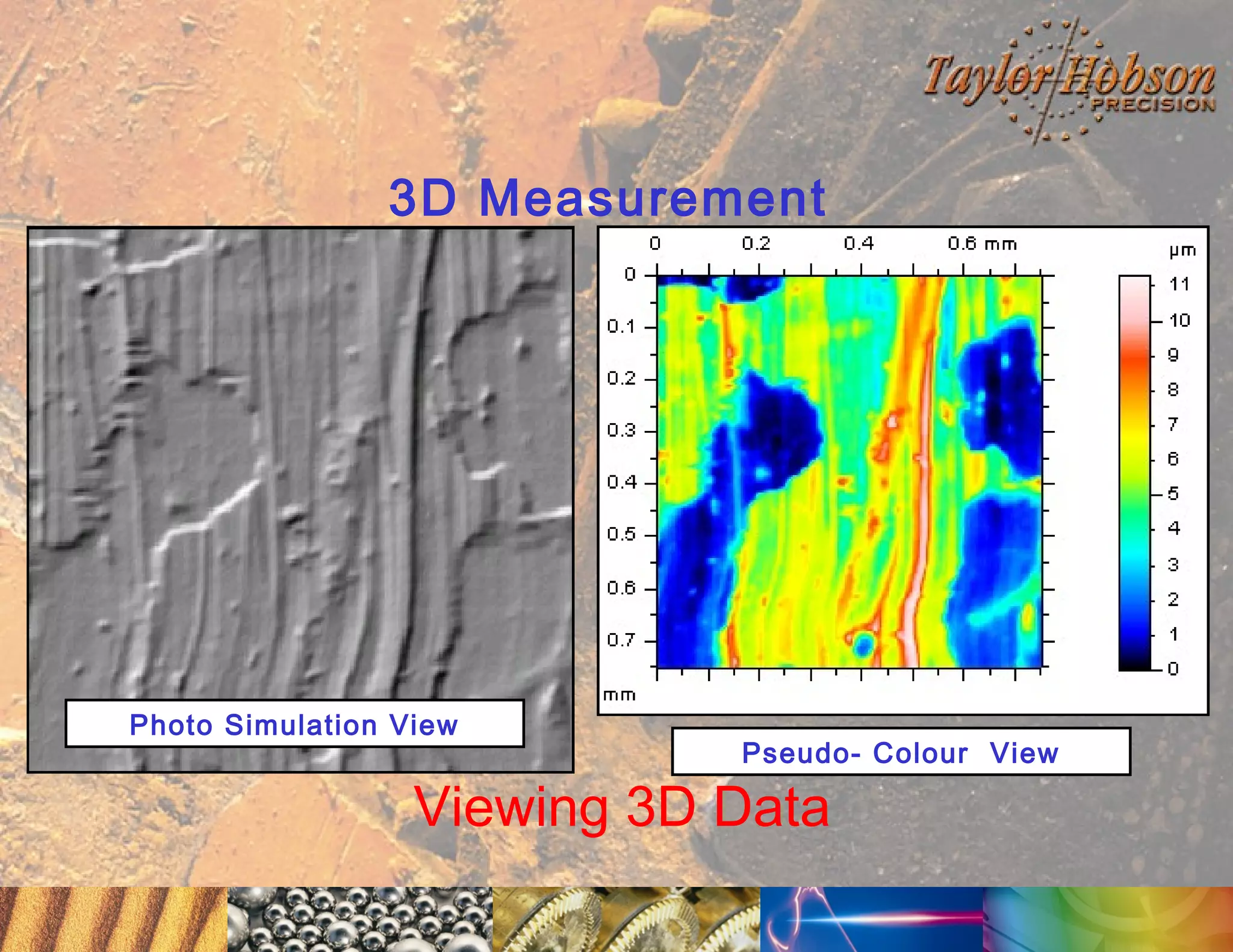

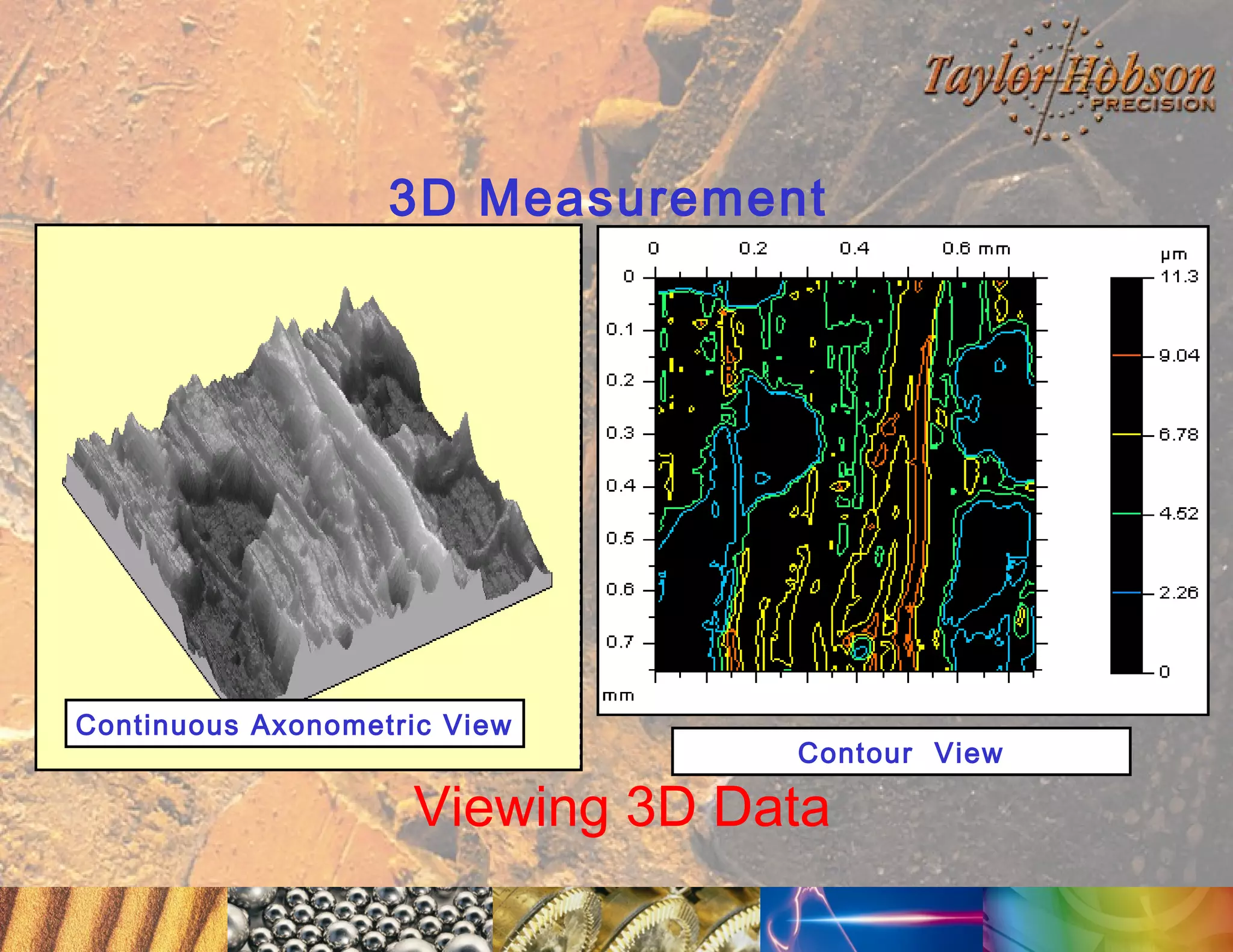

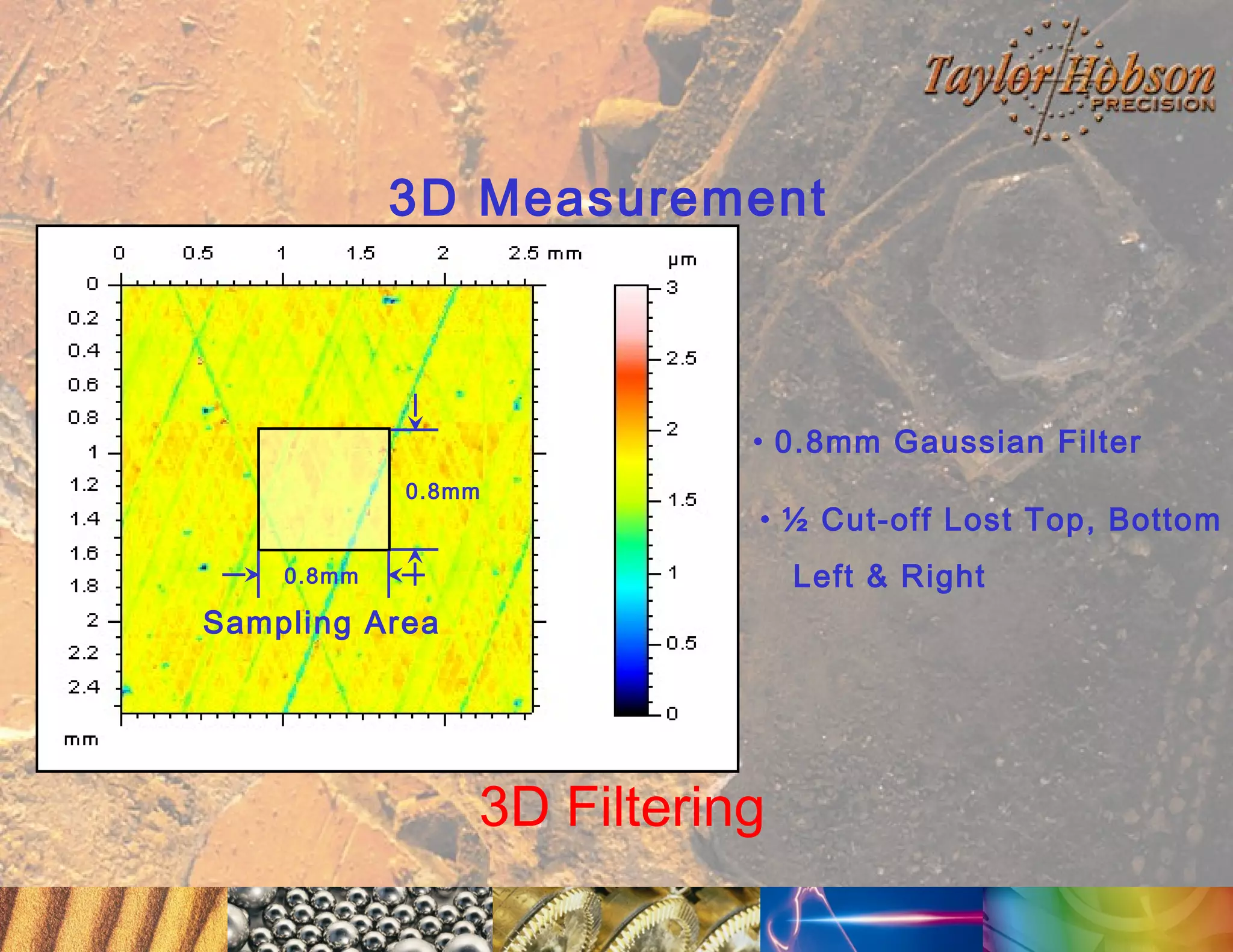

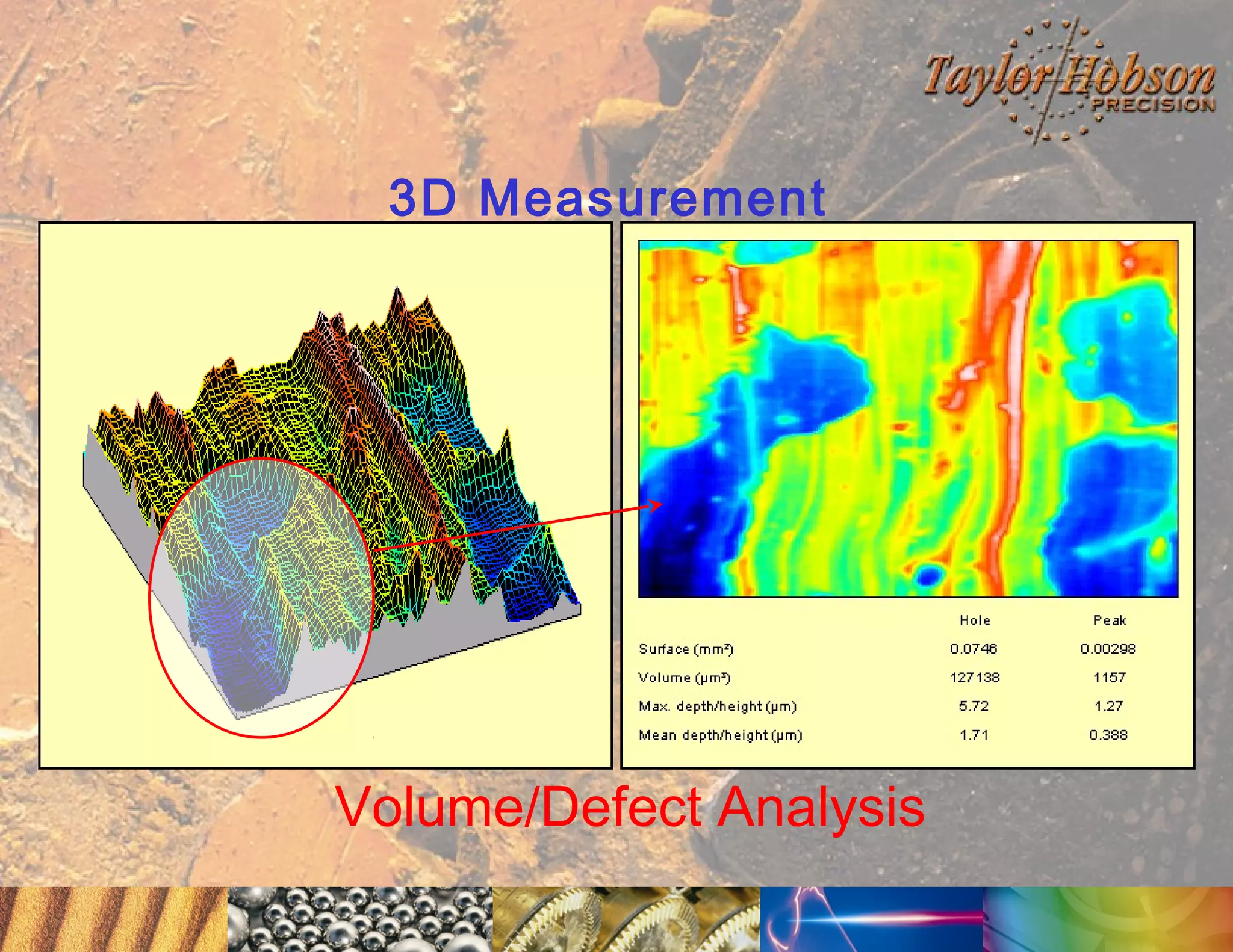

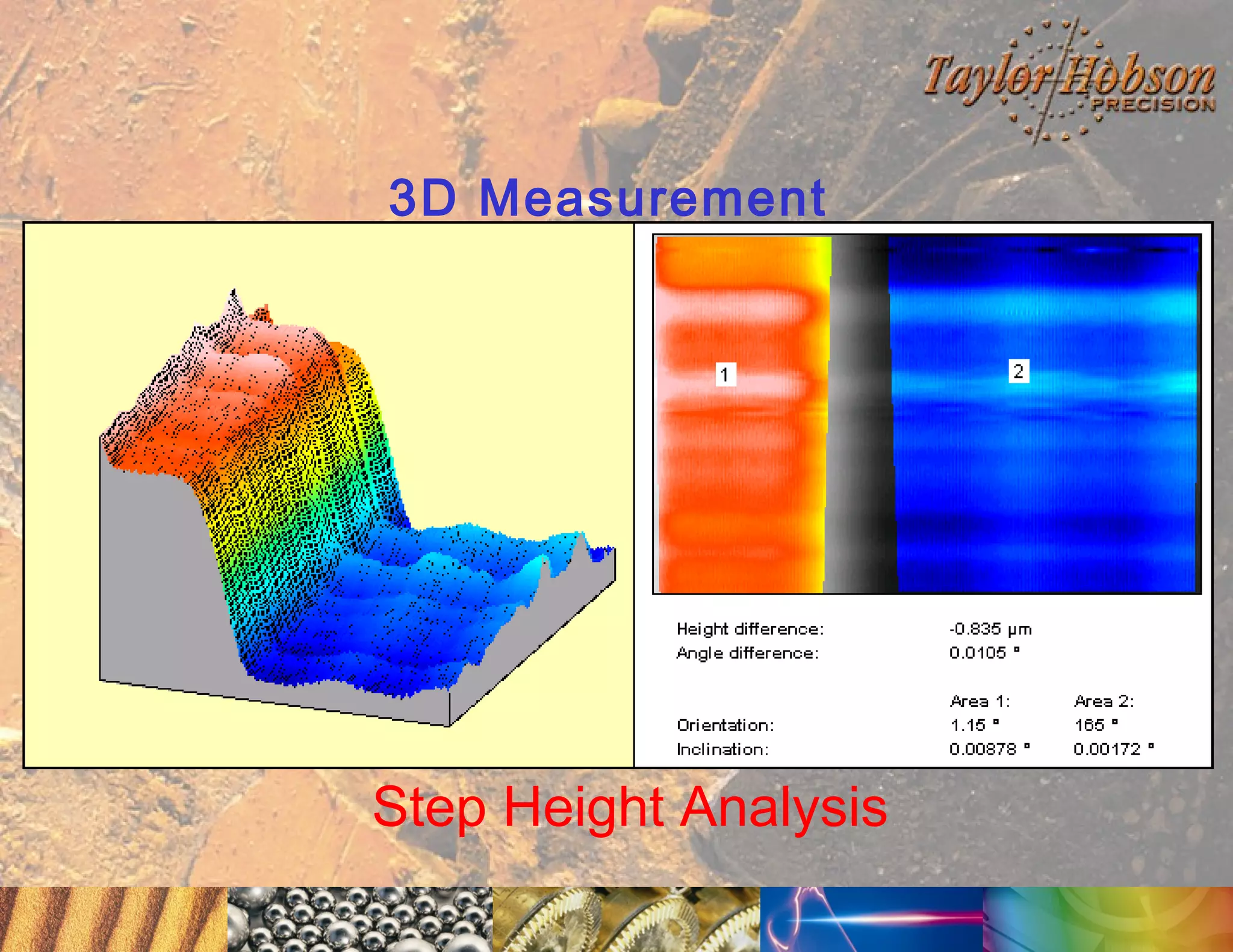

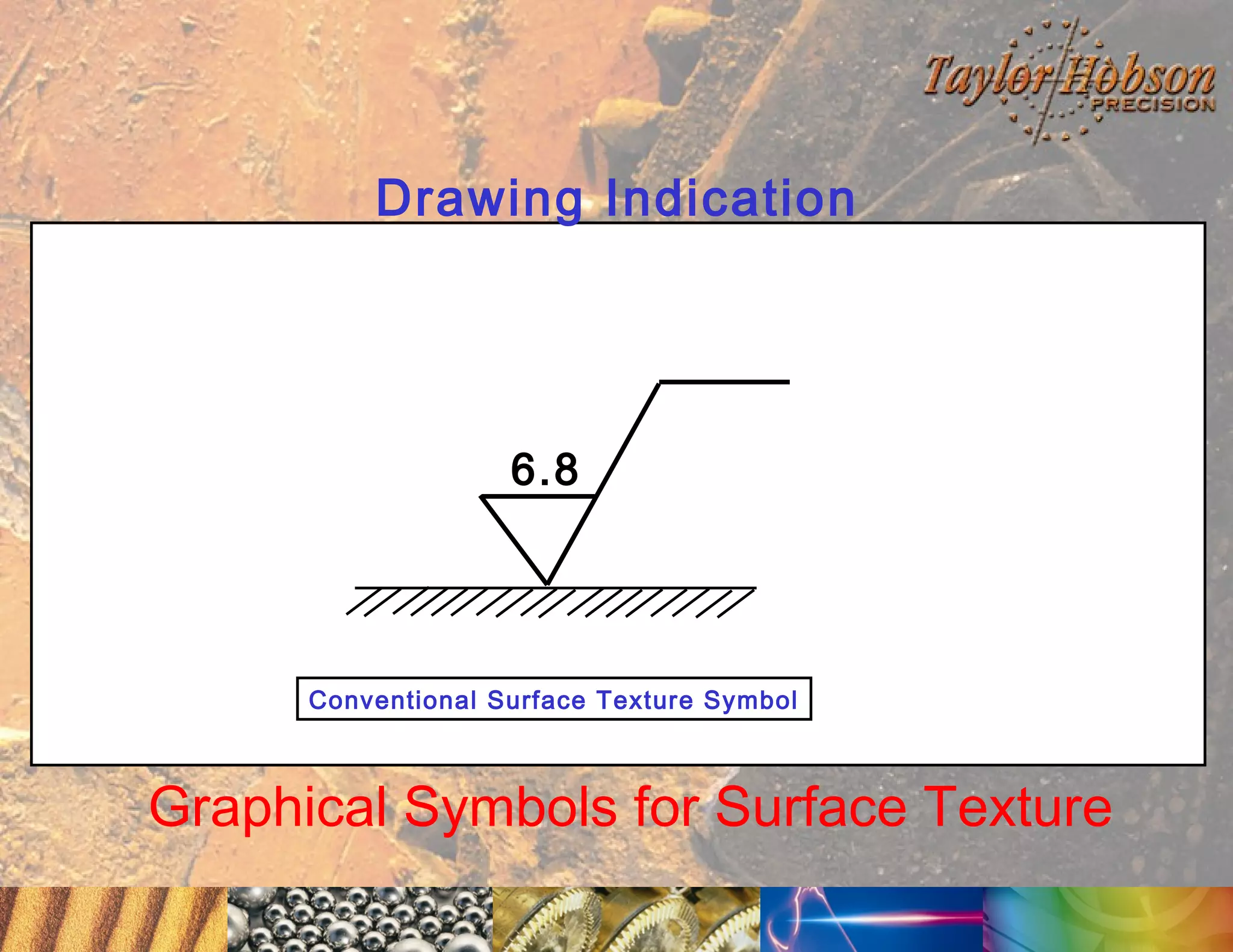

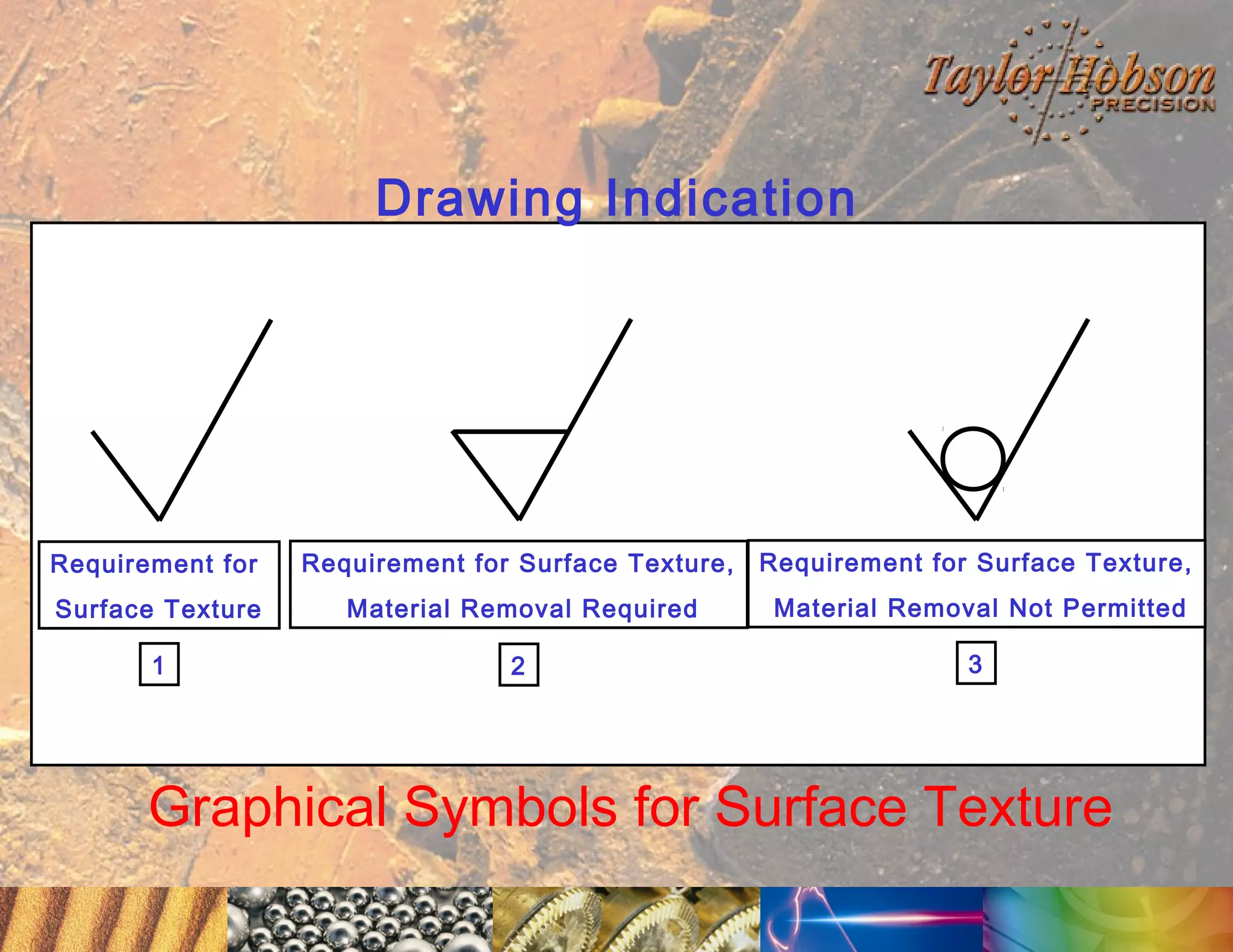

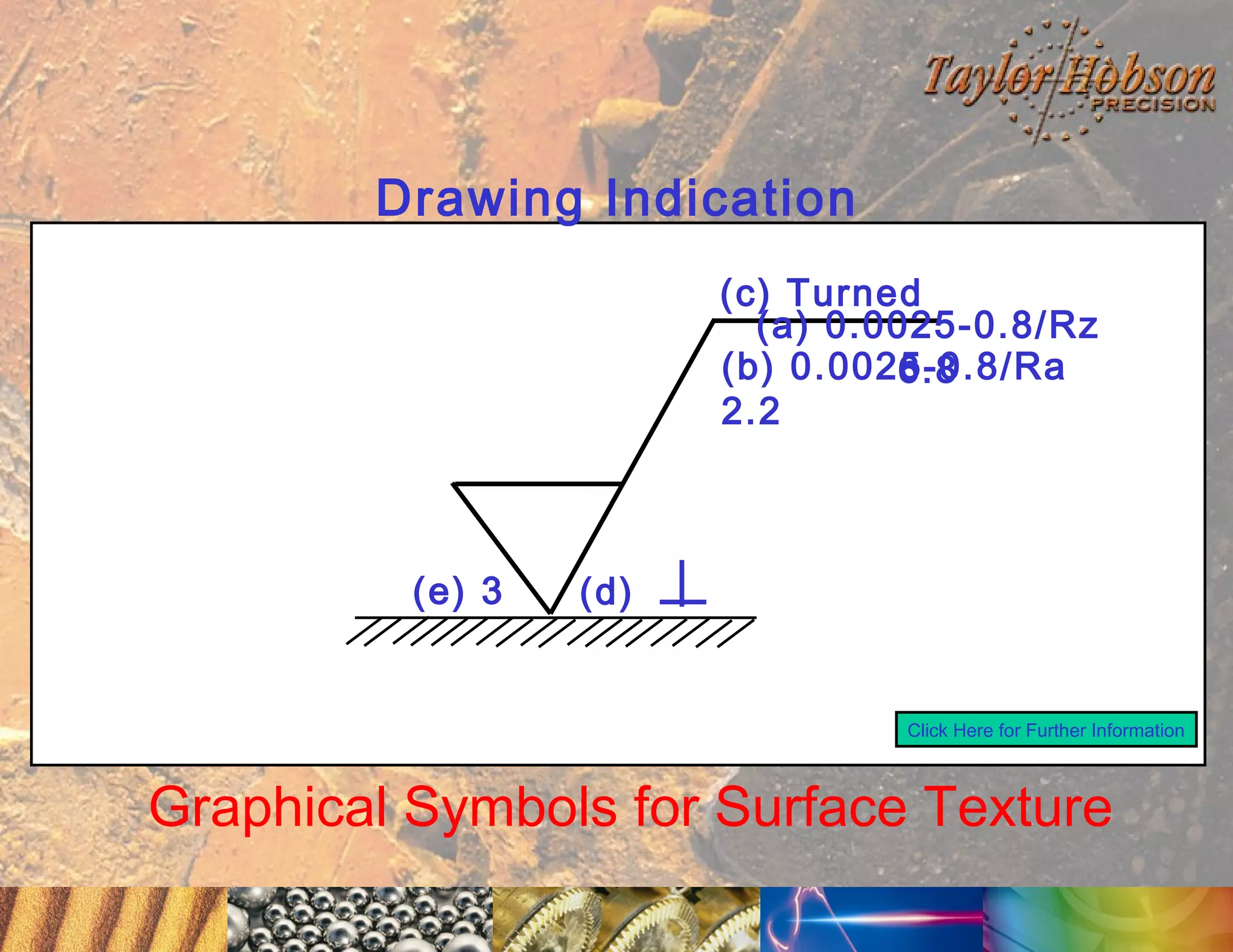

The document discusses surface metrology and measurement. It covers topics such as why surface finish needs to be measured, various measurement methods including contact and non-contact instruments, parameters like roughness and waviness, filters used to separate out different surface components, and calibration methods. Form measurement is also covered, including measurement of parameters like straightness, least squares arcs and radii.