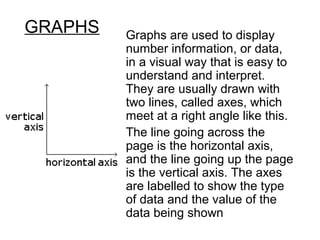

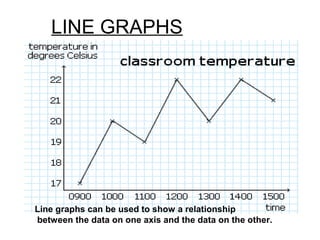

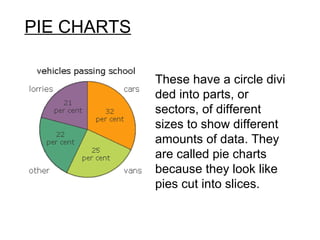

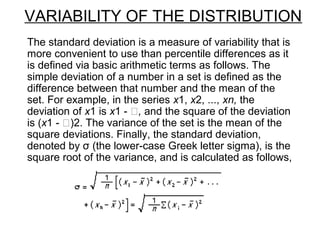

This document provides an overview of statistics as a branch of mathematics dealing with the collection, organization, and analysis of numerical data to aid decision making. It discusses the history of basic statistical methods dating back to ancient civilizations, and outlines common statistical methods like collecting primary and secondary data, tabulating and presenting data, calculating measures of central tendency and variability, using graphs to visualize data, and determining correlation between variables. The goal of statistics is to accurately represent large data sets and analyze relationships within the data.