The document is a stage 2 report for an individual project that aims to encourage STEM engagement within extra-curricular groups. It provides an overview of the conceptual design phase where concepts were generated, evaluated, and refined. It also describes initial modeling and testing. The detailed design phase is discussed where embodiment design questions were considered and prototypes were developed and tested. The report outlines the progress made against the project methodology and provides documentation to support the design process.

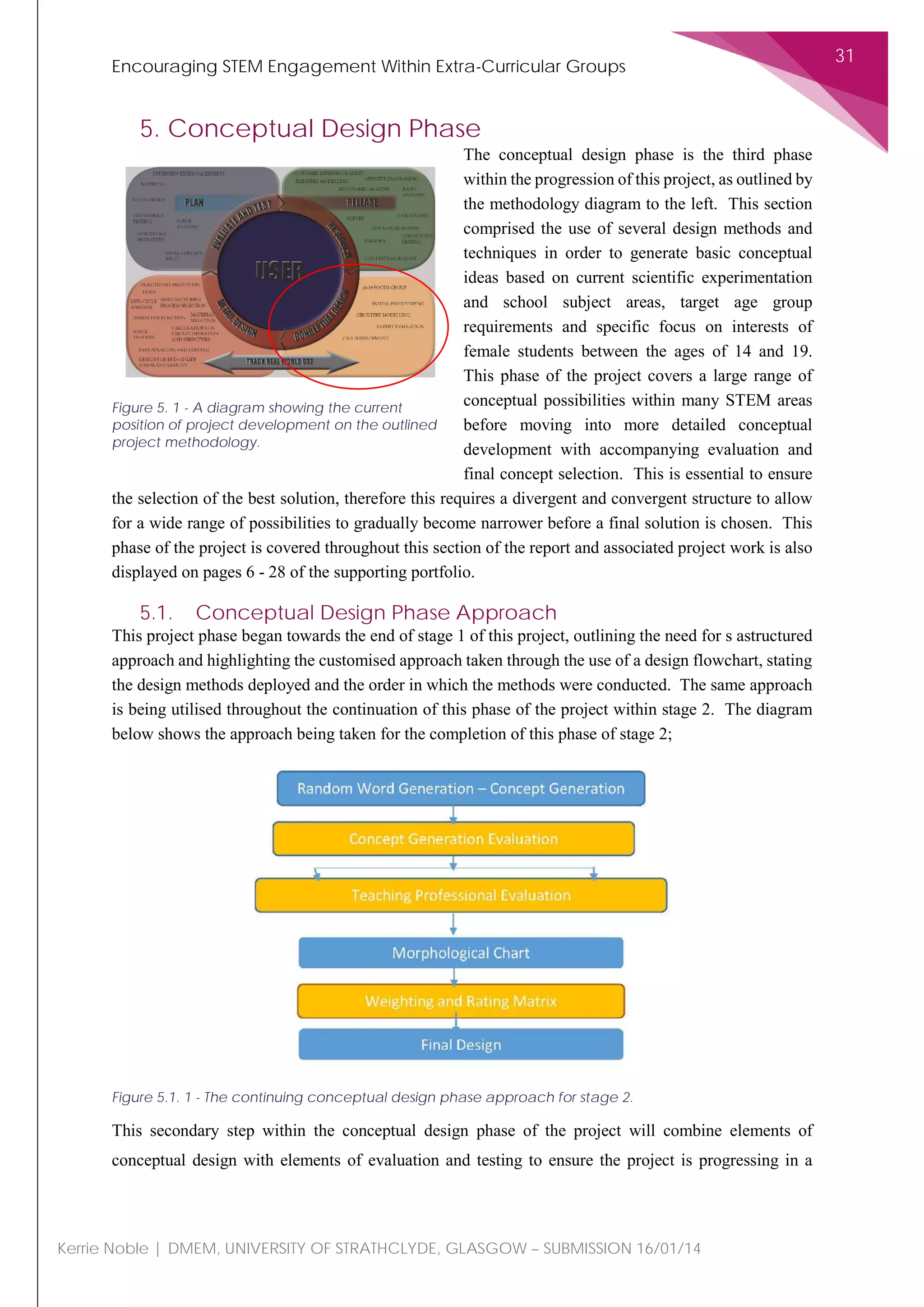

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

119

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

• Will the pressure asserted on the swivel mechanism have an adverse frictional effect on the

material? If so how much wear will this create on the material? [2]

While designing for strength conditions there are many considerations to design for and the most

appropriate considerations for this project are;

• Arm/Hand and Thumb-Finger strength – As addressed by the previous question, the force

exerted by the thumb and finger grip strength may have a significant impact on the swivel

mechanism design with regards to the material and the operational ability of the component.

• Static Push/Pull Force – As the user is required to push and pull the component to induce

rotation this force application also requires consideration. Again the 5th

percentile female static

push force and the 95th

percentile female static push force will be considered within this project

to demonstrate the extremities relating to the force applications associated with product

operation across the target user group.

• Compression Force (Fastenings) – The swivel mechanism is a statically loaded bolted joint

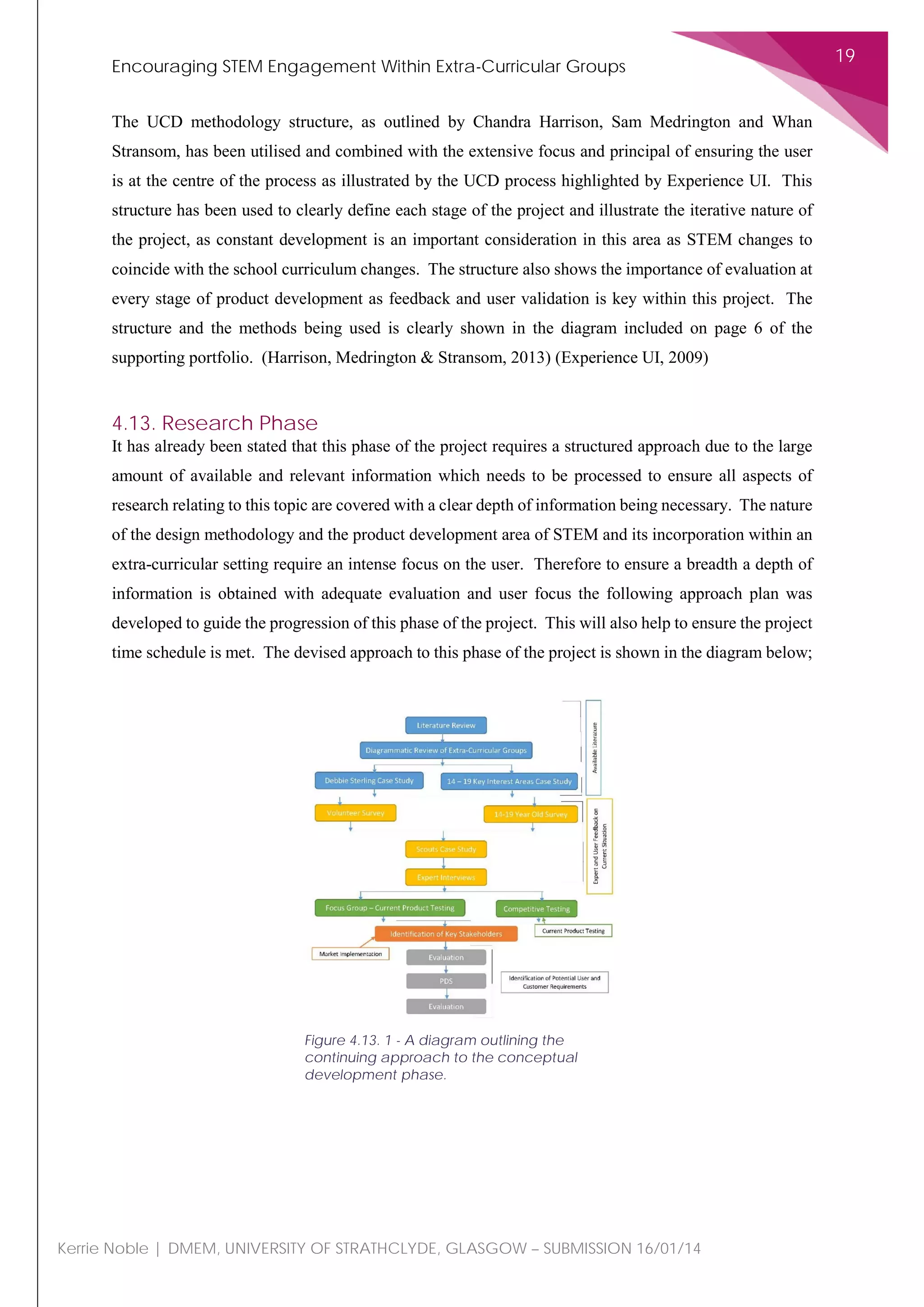

when not under the influence of user applied forces. This means that the load bearing

mechanism component needs to have sufficient material strength to withstand the static load

bearing of an M6 bolt which is specified within the current design.

These points will be further considered below.

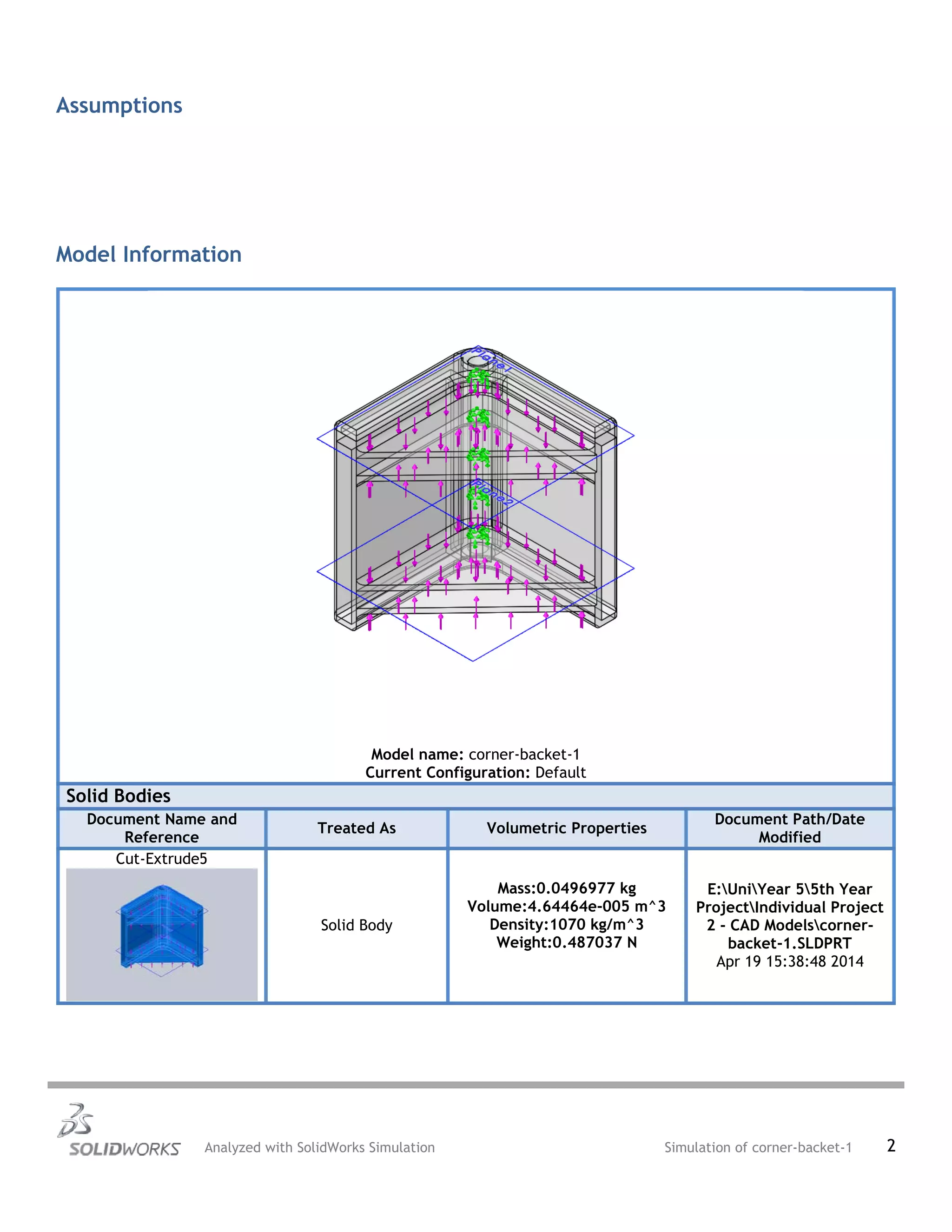

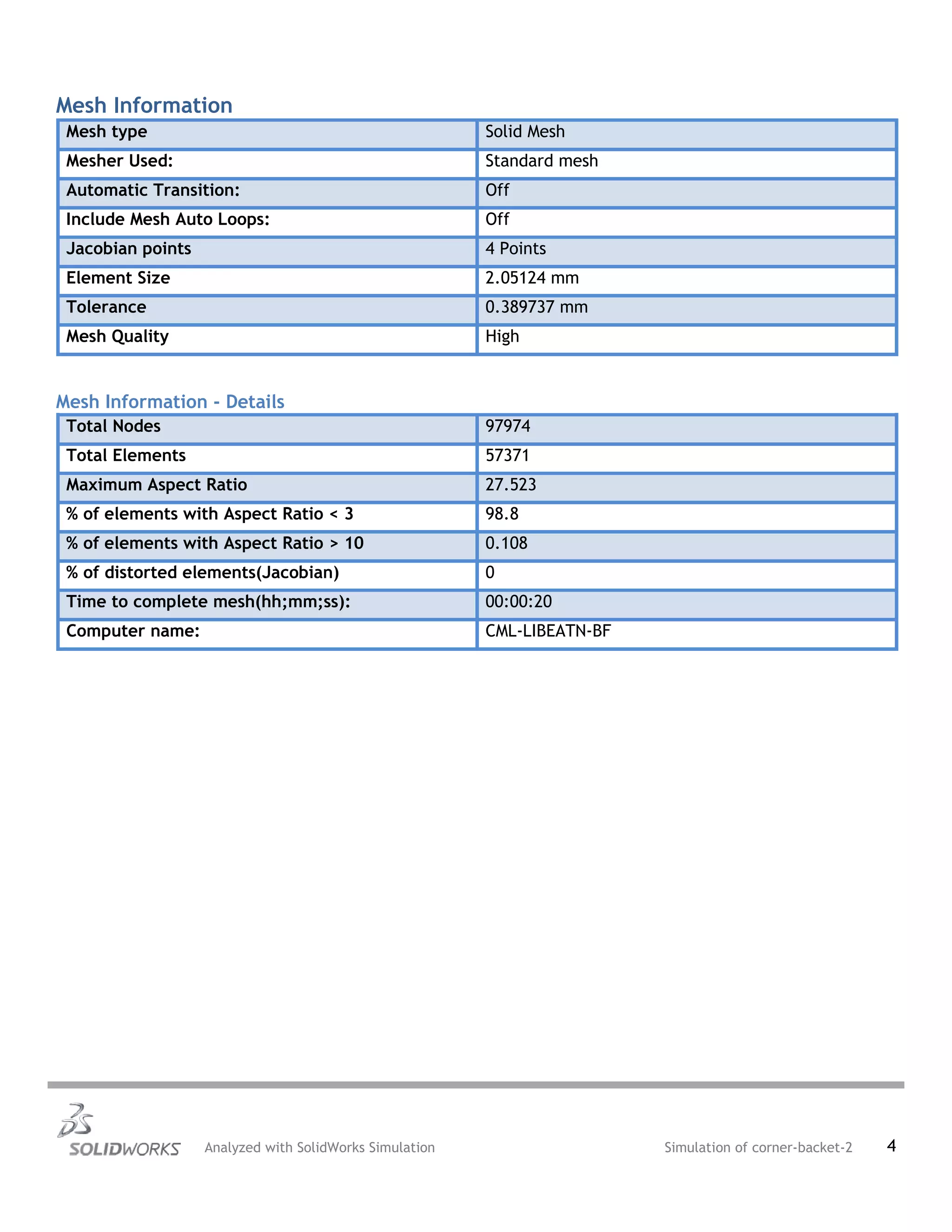

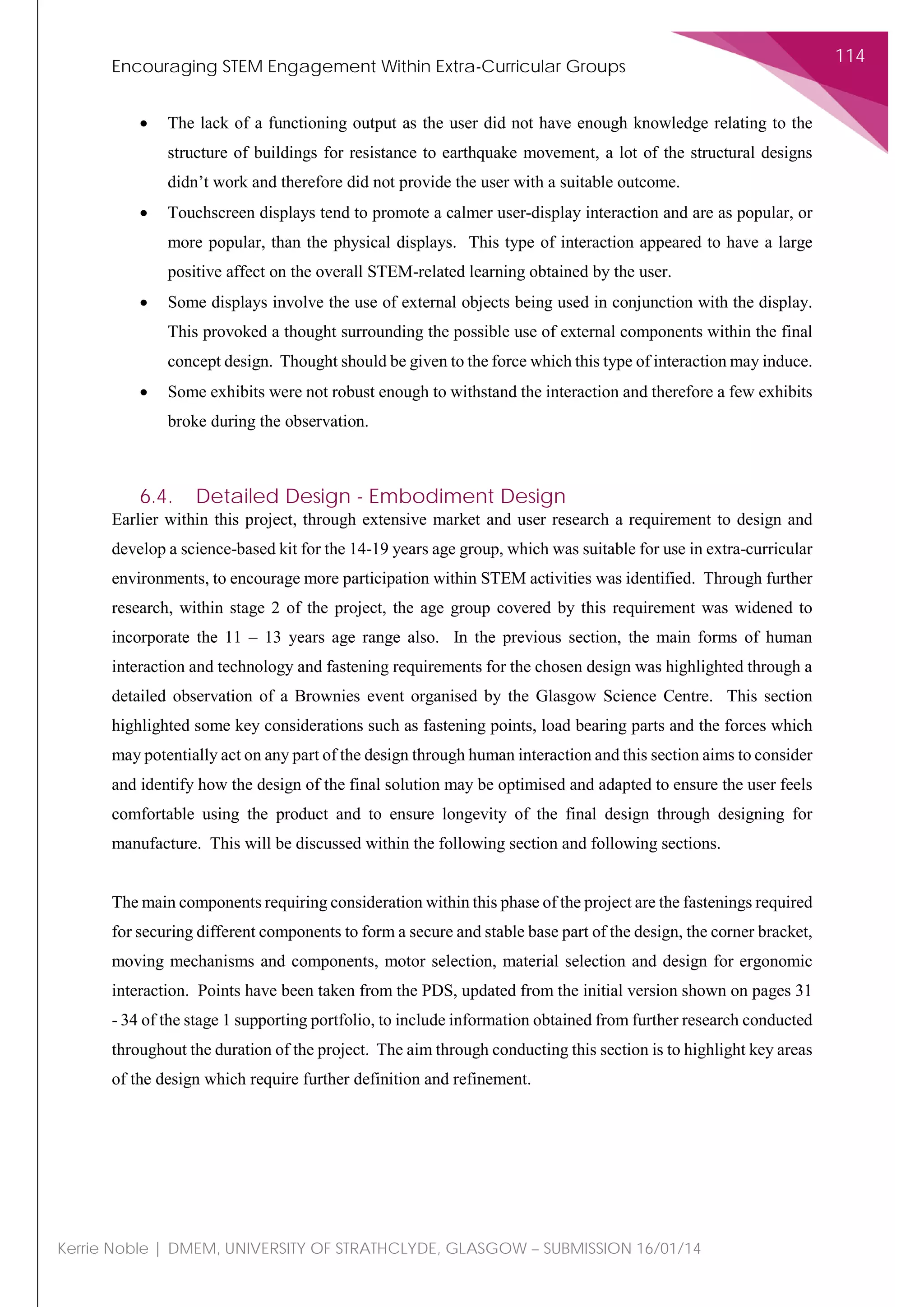

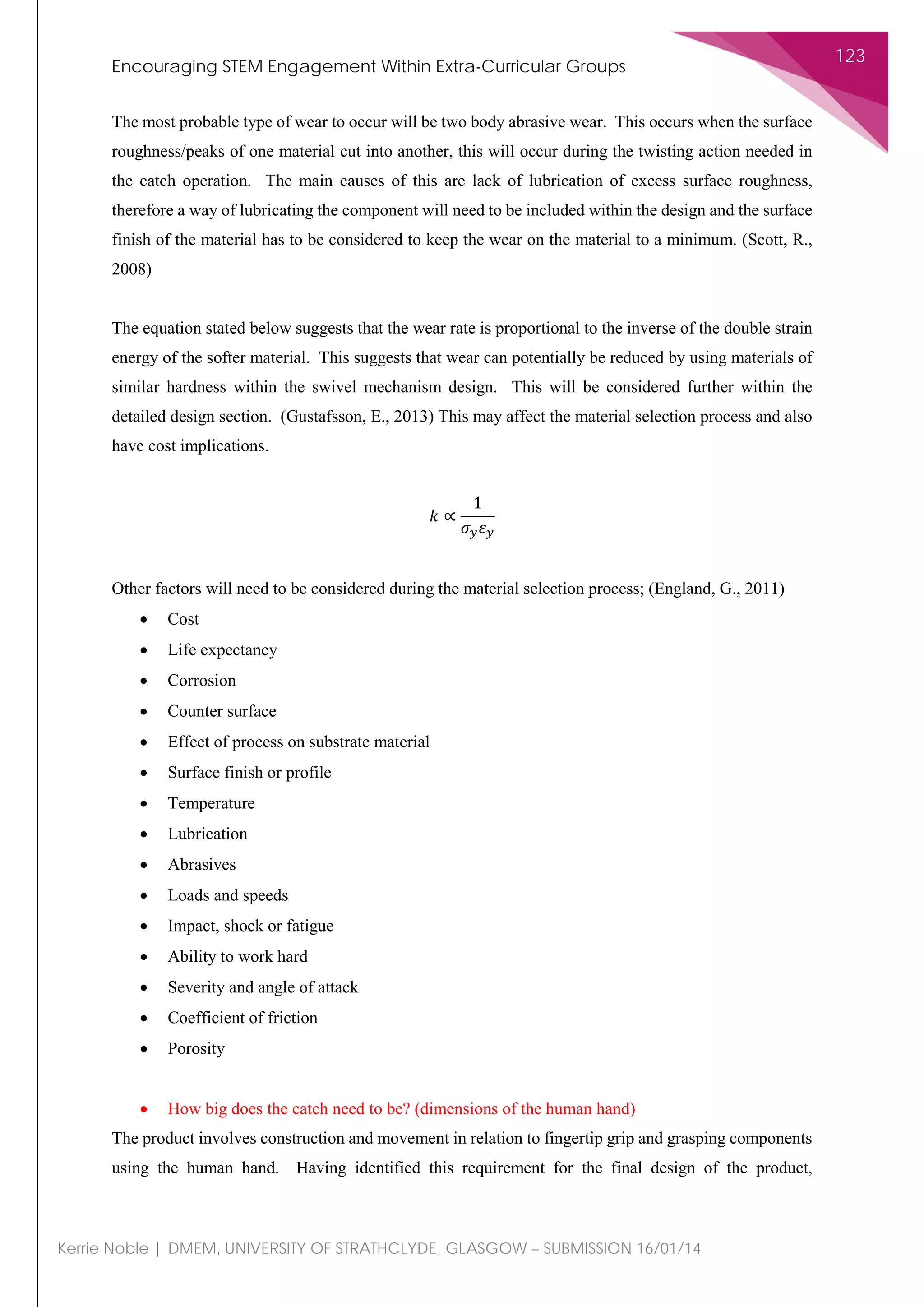

Static Push/Pull Strength

As with the section above where thumb and finger strength has been considered, the stated values within

the static push/pull strength analysis are also taken assuming that the product will be utilised within the

normal seated position, therefore meaning the users’ arm is bent at 90 degrees with the arm parallel to

the ground so elbow flexion is taken as Ω/2.

5th

percentile male push strength

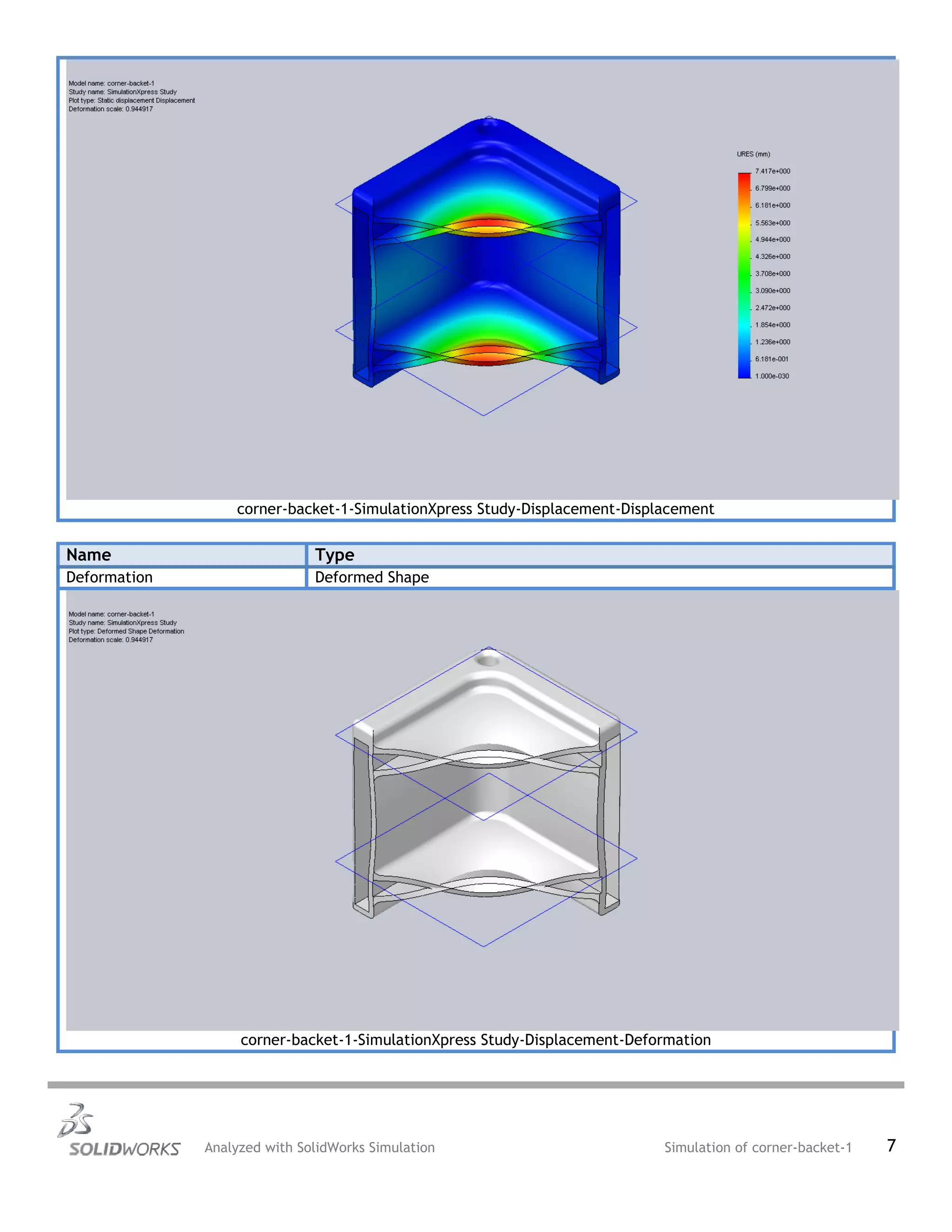

Figure 6.4. 3 - A diagram

outlining the push/pull strength

discussed within the

embodiment design.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-120-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

209

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

References

Adams, J.A. (1987). Historical review and appraisal of research on the learning, retention, and transfer

of human motor skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 41-74

APIS, 2011, Acid Deposition, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.apis.ac.uk/overview/pollutants/overview_Acid_deposition.htm, accessed 22/04/2014

Argotec, 2014, Glossary, [ONLINE] Available at; http://www.argotec.com/RF_Glossary.html,

accessed 22/04/2014

ASTM, 2014, Fire standards and flammability standards, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.astm.org/Standards/fire-and-flammability-standards.html , accessed 22/04/2014

BBC News, 2013 Scottish Scout Numbers on the Rise, Online, Available at www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-

scotland-22230007, Accessed 17/10/13

BCS, 2013, Grand Theft Auto V, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.bcs.org/content/conWebDoc/51507 accessed 10 January 2014

Beardmore, R., 2013, Anthropometric Data, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.roymech.co.uk/Useful_Tables/Human/Human_sizes.html , accessed 22/04/2014

Beer, Ferdinand P.; E. Russel Johnston, Jr. (1996). Vector Mechanics for Engineers (Sixth ed.).

McGraw-Hill. p. 397. ISBN 0-07-297688-8.

Biggs, J., 1993, “What do inventories of students’ learning processes really measure? A theoretical

review and clarification,” British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63 (1): 3-19

Bolt Depot, 2014, About fastener materials, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.boltdepot.com/fastener-information/materials-and-grades/materials.aspx, accessed

22/04/2014

Boyce, G., Williams, S., Kelly, A., & Yee, H., 2001, “Fostering deep and elaborative learning and

generic (soft) skill development: Strategic use of case studies in accounting education,” Accounting

Education, 10 (1), 37-60

Carbon Trust, 2014, Carbon Footprinting Guide, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.carbontrust.com/resources/guides/carbon-footprinting-and-reporting/carbon-footprinting,

accessed 22/04/2014

Case Western Reserve University, 2014, Thermal properties of polymers, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://plc.cwru.edu/tutorial/enhanced/files/polymers/therm/therm.htm, accessed 22/04/2014

D4S, 2014, Design for Sustainability, [ONLINE] Available at; http://www.d4s-de.org/, accessed

22/04/2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-210-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

210

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2012, Engaging the Public in Science and Engineering,

Online, Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/engaging-the-public-in-science-and-

engineering--3/supporting-pages/inspiring-students-to-study-science-technology-engineering-and-

mathematics, Accessed 14/10/13

Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2012, Engaging the Public in Science and Engineering,

Online, Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/engaging-the-public-in-science-and-

engineering--3, Accessed 14/10/13

Department for Education, 2008, After-school Science and Engineering Clubs Evaluation: Final Report,

London

Department for Education, 2010, The STEM Cohesion Programme: Final Report, London

Department of Further Education, Employment, Science and Technology (Australia), 2013, Female

Participation in STEM Study and Work in South Australia 2012, Adelaide

Dow Corning, 2012, Application centre glossary, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CC8QFjAA&url=h

ttp%3A%2F%2Fwww.dowcorning.com%2Fcontent%2Fpublishedlit%2F11-2092.pdf&ei=O2g8U-3-

B4LRhAe374CQCg&usg=AFQjCNEjhs0v5RvdqM4ArjwiJv0tqBMz-A&sig2=N92eRTSK2-

vcOXZfB7YNXQ , accessed 22/04/2014

Dowson, Duncan (1997). History of Tribology, 2nd Edition. Professional Engineering Publishing.

ISBN 1-86058-070-X.

England, G., 2011, Reducing Wear by Using Thermal Spray Coatings, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.gordonengland.co.uk/wear.htm#TSC1, accessed 22/04/2014

EU Commission, 2014, Energy and Environment, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/energy/index_en.htm, accessed 22/04/2014

Eurostat (European Commission), 2011, Education Statistics, Brussels

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, 2010, Subject Choice in

STEM: Factors Influencing Young People (aged 14-19) in Education (A systematic review of the UK

literature), University of London

Experience UI, 2009, User Centred Design Definition, Online, Available at; experience.expressionz.in,

Accessed 14/10/13

Facebook, 2014, 1st

Facebook Scout Group, [ONLINE] Available at;

https://www.facebook.com/groups/2450689742/ accessed 9 January 2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-211-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

211

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

Freudenrich, C., 2014, How rubber works, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://science.howstuffworks.com/rubber.htm/printable , accessed 22/04/2014

Girl Scouts of America Research Institute, 2012, Generation STEM: What Girls Say About Science,

Technology, Engineering and Maths, Lockheed Martin

GoldieBlox, 2013, GoldieBlox: Building games for girls to inspire future engineers, Online, Available

at www.goldieblox.com/pages/about, Accessed 18/10/13

Gustafsson, E., 2013, Investigation of friction between plastic parts, Master's thesis in Polymer

tribology, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=0CEwQFjAD&url=h

ttp%3A%2F%2Fpublications.lib.chalmers.se%2Frecords%2Ffulltext%2F181751%2F181751.pdf&ei

=2Jo5U762L4iA7Qa-

FQ&usg=AFQjCNGrWQ05wZjVPkXNFIaVSQ8dUn16mw&sig2=L7LRs9rRJfo557QlpKHwIg ,

accessed 22/04/2014

Hamaker, J., 2009, The Rise of Social Networking Sites and Their Effects on Our Lives, [ONLINE]

Available at; http://ezinearticles.com/?The-Rise-of-Social-Networking-Sites-and-Their-Effects-on-

Our-Lives&id=2887717 accessed 9 January 2014

Harrison, Medrington & Stransom, 2013, User Centred Design Research Methods for Mobile Industry

Practitioners, WI Journal of Mobile Media, Sound Moves, Vol.7 No.1, March 2013

IMBD, 2013, Most Popular Video Games Released in 2013, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.imdb.com/search/title?sort=moviemeter&title_type=game&year=2013,2013 accessed 9

January 2014

IPSOS MORI Social Research Institute, 2011, Public Attitudes to Science, Department for Business

Innovation and Skills, London

Johnson, T., 2014, Plastics in children’s toys, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://composite.about.com/od/Plastics/a/Plastics-In-Children-S-Toys.htm , accessed 22/04/2014

Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2009, Manufacturing Engineering and Technology, Sixth Edition, Prentice Hall,

Singapore

Keithley, 2001, Volume and Surface Resistivity Measurements of Insulating Materials Using the Model

6517A Electrometer/High Resistance Meter, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDYQFjAB&url=

http%3A%2F%2Fwww.keithley.co.uk%2Fdata%3Fasset%3D6069&ei=SmY8U8qTDMqshQeQyYG

gCw&usg=AFQjCNGjYOiwffUs37foyRMum9HolCE9Vg&sig2=7nBjMy2n0EXk12z541i7iw ,

accessed 22/04/2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-212-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

212

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

Kent, R., 2009, What’s your process energy fingerprint?, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.ptonline.com/articles/whats-your-process-energy-fingerprint, accessed 22/04/2014

K’NEX, 2013, Online, Available at www.knex.com/products, Accessed 17/10/13

Knowledge Project, 2013, Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Controls in Aquatic Ecosystems,

[ONLINE] Available at; http://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/eutrophication-causes-

consequences-and-controls-in-aquatic-102364466, accessed 22/04/2014

Lego Mindstorm picture http://education.lego.com/en-gb/lego-education-product-

database/mindstorms/9797-lego-mindstorms-education-base-set

Lego education2, 2013, http://shop.legoeducation.com/gb/product/lego-mindstorms-education-nxt-

base-set-9797-29/

Lord Sainsubury, 2007, The Race to The Top: A Review of Government’s Science and Innovation

Policies, October 2007

Lyondell, 2014, Mould shrinkage, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDgQFjAB&url=h

ttp%3A%2F%2Fwww.lyondellbasell.com%2Ftechlit%2Ftechlit%2FTech%2520Topics%2FGeneral%

2FMold%2520Shrinkage.pdf&ei=fGI8U7zRApOShQflsoHADw&usg=AFQjCNGta2DvS0-

Sh_rAIXBeyYw5BVPBmg&sig2=6WFmJs5-mll4o5fFKcX5TQ&bvm=bv.63934634,d.ZWU ,

accessed 22/04/2014

Lyondell Chemical Company, 2014, A guide to polyolefin sheet extrusion, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.lyondellbasell.com/techlit/techlit/Brochures/Sheet%20Extrusion%209531.pdf, accessed

22/04/2014

Mashable, 2013, Social Networking, [ONLINE] Available at; http://mashable.com/category/social-

networking/ accessed 9 January 2014 (and social networking image)

Marteniuk, R. (1976). Information Processing in Motor Skills. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Marton, F., & Säljö, R., 1976a, “Qualitative differences in learning I. Outcomes and processes,” British

Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 4-11

Marton, F., & Säljö, R., 1976b, “On qualitative differences in learning II. Outcomes as a function of the

learners’ conception of the task,” British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 115-127

Mat Web, 2014, Material property search, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.matweb.com/search/search.aspx , accessed 22/04/2014

Mayer, R.E., & Chandler, P., 2001, “When learning is just a click away: Does simple user interaction

foster deep understanding of multimedia messages?”, Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 93, No.

2, 390-397, American Psychological Association INC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-213-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

213

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

Mayer, R.E., & Moreno, R., 2003, “Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning,”

Educational Psychologist, 38 (1) 43-52, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, INC.

Merriam-Webster, 2014, Back-pressure, [ONLINE] Available at; http://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/back%20pressure, accessed 22/04/2014

Met Office, 2014, Monthly temperature records by country, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/extremes/monthly_temperature_country.html#highest_daily_

maximum_england , accessed 22/04/2014

Micro Chem, 2014,Material properties definitions, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.microchem.com/Tech-MaterialPropDefs.htm , accessed 22/04/2014

Mirror, 2013, 2011 Census: The main 20 languages spoken in the UK, available at

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/2011-census-top-20-languages-1563629, accessed 30

September 2013

Mischel, W., 2013, “Personality and Assessment,” Psychology Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 15

April 2013, Hove, United Kingdom

National Academy of Engineering, 2013, Engineer Girl: Debbie Sterling, Online, Available at

www.engineergirl.org/Engineers/Directory/13512.aspx, Accessed 18/10/13

NASA, 2008, Volume I, Section 4: 4 HUMAN PERFORMANCE CAPABILITIES, [ONLINE]

Available at; http://msis.jsc.nasa.gov/sections/section04.htm , accessed 22/04/2014

NIST, 2006, Specular Gloss, [ONLINE] Available ay;

http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=7&ved=0CF0QFjAG&url=ht

tp%3A%2F%2Fwww.nist.gov%2Fcalibrations%2Fupload%2Fsp250-70.pdf&ei=6mg8U-

meDYKrhQff3IHwCA&usg=AFQjCNFI7jdI51nrC6oqD_mrzJTdwKpRlA&sig2=tYlVVbjhSoXLzQ-

fqymYGQ , accessed 22/04/2014

Office for National Statistics, Historic UK Population Pyramid, Census Figures 2011, Online, Available

at www.ons.gov.uk/ons/interactive/historic-uk-population-pyramid/index.html, Accessed 14/10/13

Persson, B. N.; Volokitin, A. I (2002). "Theory of rubber friction: Nonstationary sliding". Physical

Review B 65 (13): 134106. Bibcode:2002PhRvB..65m4106P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.65.13410

Pintirch, P.R., 2002, “The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching and assessing,” Theory

into Practice, Vol. 41, No. 4, Revising Bloom’s Taxonomy, 219-225

Polymer Engineering Guide, 2012, Elastomer engineering guide, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=6&ved=0CFkQFjAF&url=ht

tp%3A%2F%2Fwww.jameswalker.biz%2Fen%2Fpdf_docs%2F148-elastomer-engineering-

guide&ei=OmM8U72JM8-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-214-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

214

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

AhAegk4CABw&usg=AFQjCNH7wIHA9RDs8IUjylQbpICq84QOgA&sig2=TnZv3fl1OWzLuqh7w

zYAXQ , accessed 22/04/2014

TEDxTalks, 2013, Inspiring the next generation of female engineers: Debbie Sterling at TEDxPSU,

Online, Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEeTLopLkEo, Accessed 19/10/13

The design society, 2011, Design Procedures for Statically Loaded Bolted Joints, [ONLINE] Available

at; http://www.bath.ac.uk/idmrc/themes/projects/delores/co-design-website/dpg/bol/bol3.html ,

accessed 22/04/2014

Resin Supplies, 2014, Casting Resins, [ONLINE] Available at; http://www.resin-

supplies.co.uk/casting%20resin%20detailed.htm , accessed 22/04/2014

The Royal Academy of Engineering, 2007, Educating Engineers for the 21st Century, London

The Russell Group of Universities, (February 2009), STEM-Briefing, London

Sandoval, W. A., 2004, “Understanding student’s practical epistemologies and their influence on

learning through inquiry,” Sci Ed, 89: 634-656, Wiley Periodicals INC.

Scott, R., 2008, Basic Wear Modes in Lubricated Systems, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.machinerylubrication.com/Read/1375/wear-modes-lubricated , accessed 22/04/2014

Singer, R.N. (1975). Motor Learning and Human Performance (2nd Ed.). New York: Macmillan

Skinner, B. F., 2012, “I The Science of Learning and the Art of Teaching,” Readings in Educational

Psychology, Learning and Teaching, E. Stones, Routledge Library Editions: Education, 4th

May 2012,

pp. 301-309

Startasys, 2014, Finishing Touch Smoothing Station: Expanding Possibilities, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.stratasys.com/applications/finishing/smoothing-fdm-parts , accessed 22/04/2014

Stevens, H., 2012, Employer Engagement in STEM Learning in the Heart of the South West, University

of Exeter

Sweller, 1999, “Instructional Design in Technical Areas,” Camberwell, Australia, Acer Press

Thomasnet, 2014, What is laser cutting?, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.thomasnet.com/articles/custom-manufacturing-fabricating/laser-cutting-technology,

accessed 22/04/2014

Tian, Y., & Gao, F., 1999, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 1999, 38 (9), pp 3396–3406, DOI: 10.1021/ie980535p

Publication Date (Web): August 14, 1999 Copyright © 1999 American Chemical Society

Translators Café, 2014, Electrical Resistivity, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.translatorscafe.com/cafe/EN/units-converter/electric-resistivity/d/ , accessed 22/04/2014

UL, 2014, UL 94, the Standard for Safety of Flammability of Plastic Materials for Parts in Devices and

Appliances testing, [ONLINE] Available at;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-215-2048.jpg)

![Encouraging STEM Engagement Within Extra-Curricular Groups

215

Kerrie Noble | DMEM, UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE, GLASGOW – SUBMISSION 16/01/14

http://www.ul.com/global/eng/pages/offerings/industries/chemicals/plastics/testing/flame/ , accessed

22/04/2014

Understanding energy consumption in injection moulding machine, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://www.pitfallsinmolding.com/energyeffic1.html, accessed 22/04/2014

Wiki Answers, 2014, How many miles from England to China?, [ONLINE] Available at;

http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_miles_from_England_to_China#slide=3&article=How_many

_miles_from_England_to_China, accessed 22/04/2014

Williamson Corporation, 2014, Die Temperature, [ONLNE] Available at;

http://www.williamsonir.com/die-temperature, accessed 22/04/2014

Yahoo Answers, 2011, What materials are used for children’s toys?, [ONLINE] Available at;

https://uk.answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20110418143658AAZvzSy , accessed 22/04/2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b7190c6a-ea70-4ccb-a3d1-64d537c797e7-151124225215-lva1-app6892/75/Stage-2-Report-216-2048.jpg)