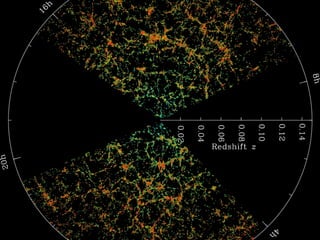

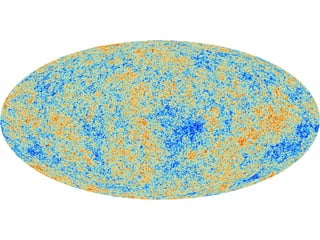

The document discusses applying dynamical systems methods to develop models of the early universe. Specifically, it discusses:

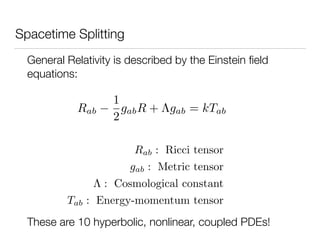

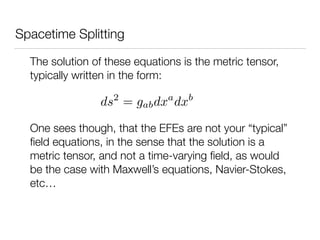

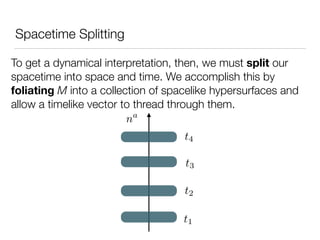

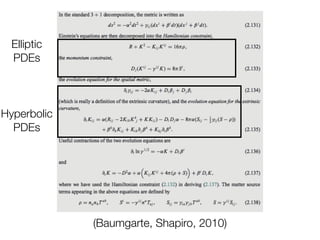

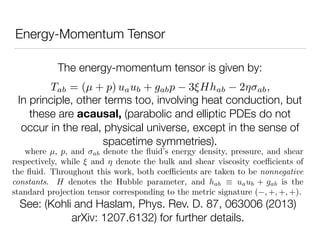

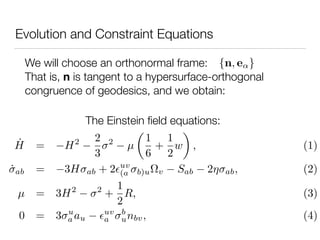

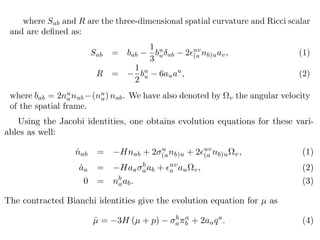

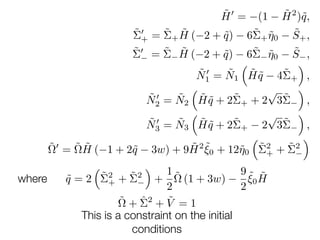

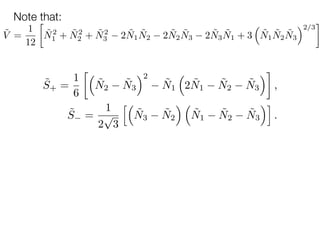

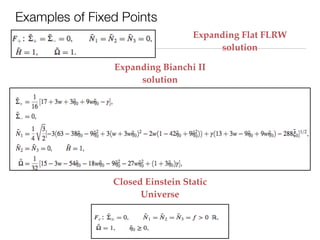

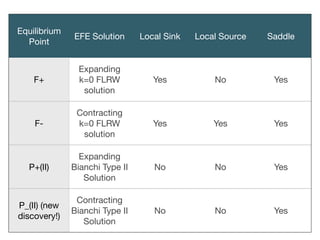

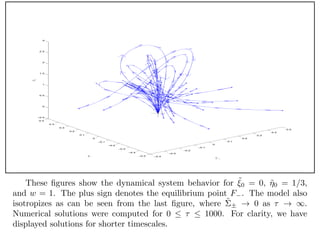

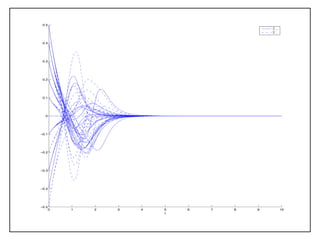

1. Applying these methods to the Einstein field equations to obtain cosmological models that are spatially homogeneous but anisotropic.

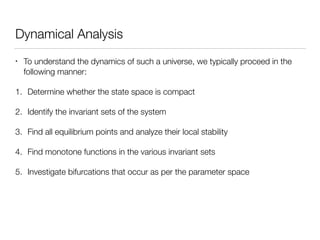

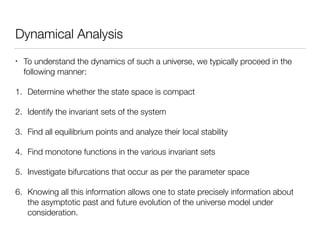

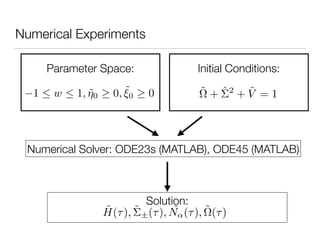

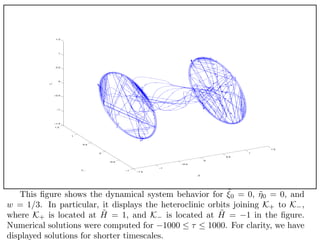

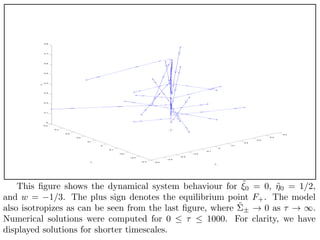

2. Describing the process of analyzing the dynamics of these models, which involves identifying invariant sets, equilibrium points, monotone functions, and bifurcations in the parameter space.

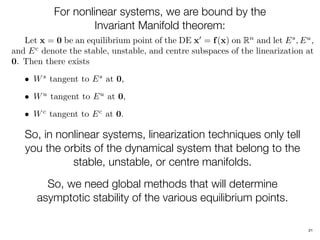

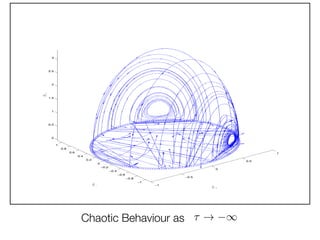

3. The importance of numerical methods in understanding the global behavior of these systems, since analytical methods are often limited to local analysis near equilibrium points.