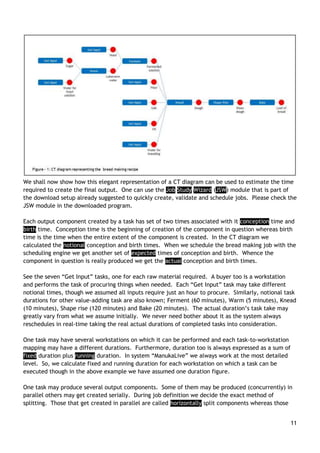

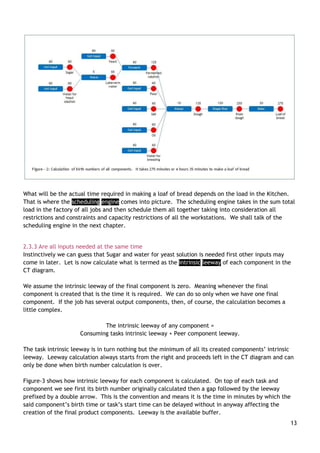

The document discusses a new method for solving the complex real-life scheduling problem in manufacturing processes, highlighting the challenges and failures of existing scheduling solutions. It introduces a Component Task Diagram (CT diagram) to represent and manage tasks and workstations effectively, integrating real-time feedback and rescheduling capabilities. The author emphasizes the importance of accurate scheduling for operational efficiency and invites readers to evaluate the proposed solution through available software downloads.

![17

References

[1] PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, PwC 2016

Global Industry 4.0 Survey - What we mean by

Industry 4.0 / Survey key findings / Blueprint

for digital success.

[2] “Is scheduling a solved problem?” - Stephen

F. Smith, Carnegie Mellon University, 5000

Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh PA 15213 USA.

sfs@cs.cmu.edu.

[3] M. L. Pinedo. Scheduling: Theory,

Algorithms, and Systems. Springer, 4th edition,

2012. p. 431.

[4] Cowling, P.; Johansson, M. - Production,

Manufacturing and Logistics

Using real time information for effective

dynamic scheduling - Elsevier: European

Journal of Operational Research 139 (2002)

230–244](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/solvingschedulingproblem-170115114914/85/Solving-the-real-life-scheduling-problem-19-320.jpg)