The document discusses key concepts related to ideal and non-ideal solutions including:

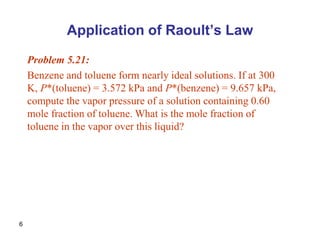

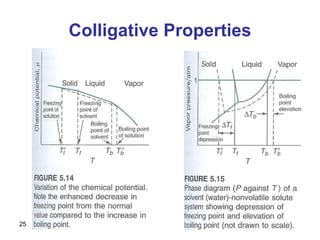

- Raoult's law describes the vapor pressure of components in an ideal solution. It states the partial vapor pressure of a component is directly proportional to its mole fraction in the liquid.

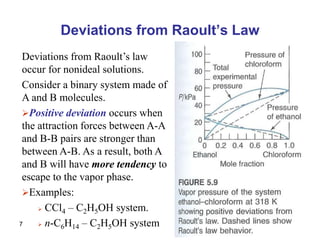

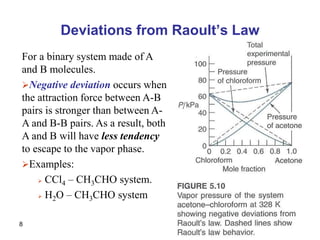

- Deviations from Raoult's law occur for non-ideal solutions where interactions between unlike molecules differ from those between like molecules.

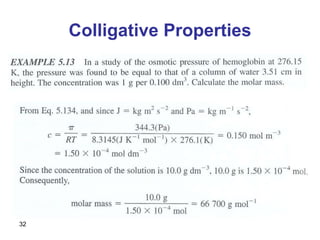

- Henry's law describes the solubility of gases in liquids, stating the concentration of a gas is directly proportional to its partial pressure above the solution.

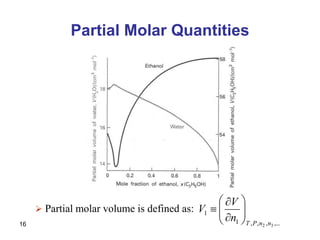

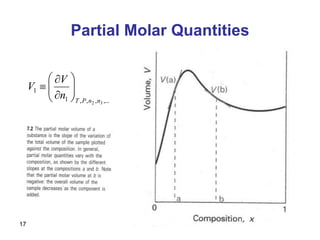

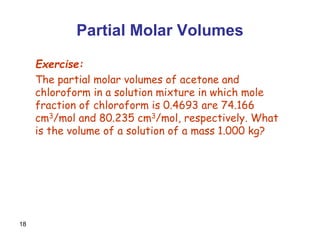

- Partial molar quantities allow treatment of non-ideal solutions by considering how properties change with changes in composition.