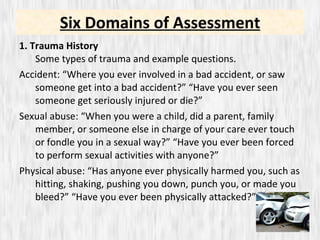

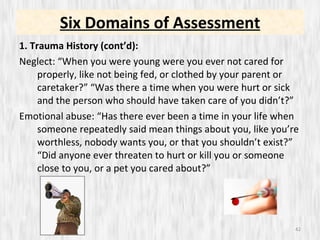

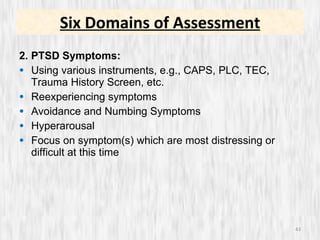

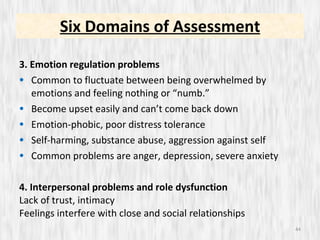

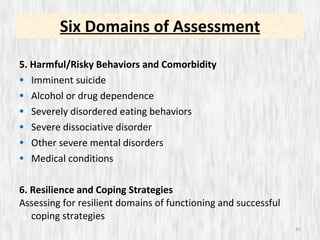

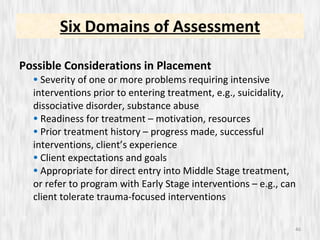

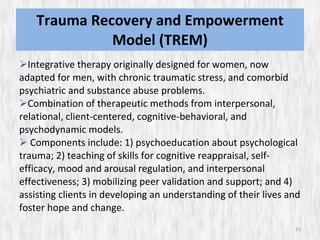

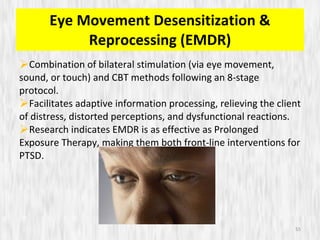

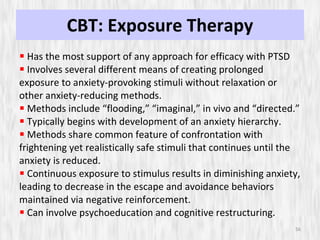

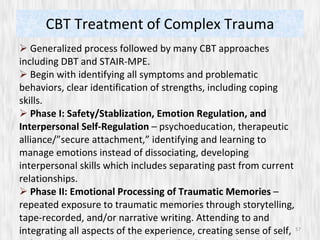

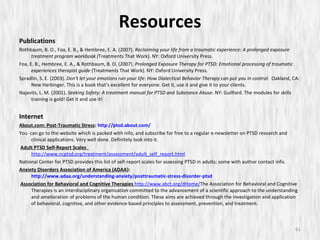

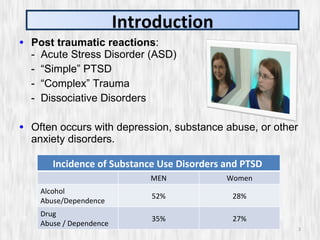

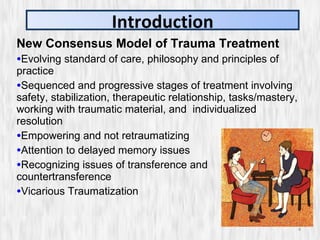

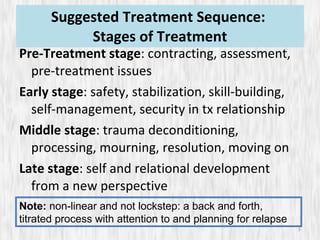

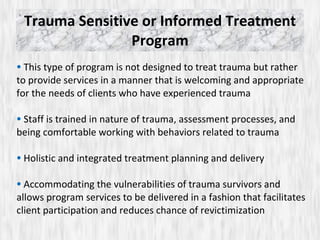

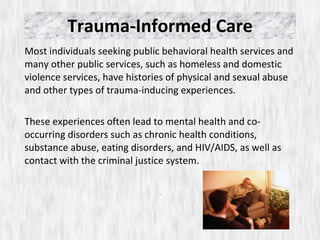

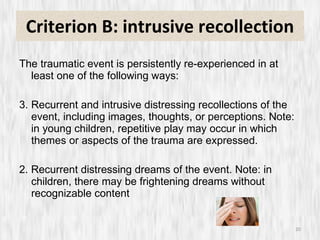

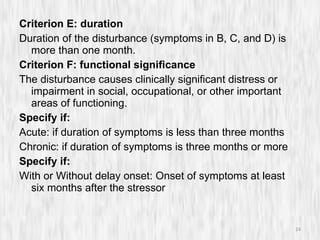

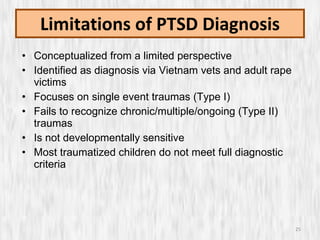

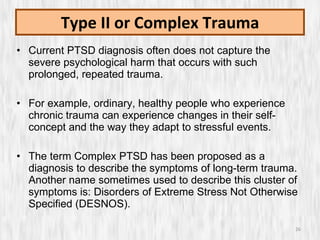

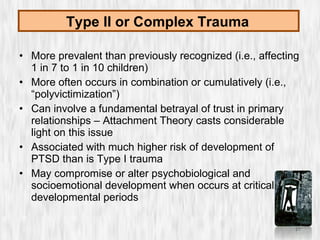

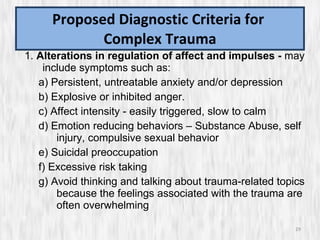

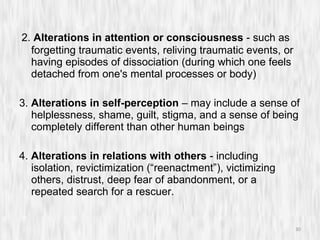

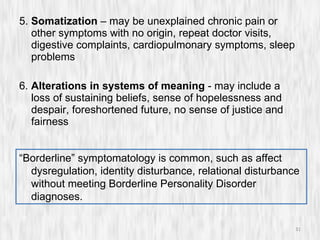

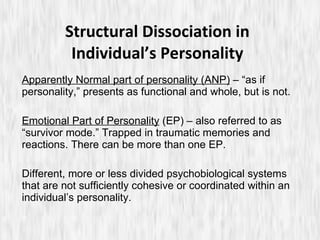

The document discusses simple and complex trauma, including definitions, prevalence, risk factors, common reactions and diagnoses like Acute Stress Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. It also outlines stages of trauma treatment from safety and stabilization to resolution, and principles of trauma-informed care like reducing retraumatization and understanding the impacts of trauma.

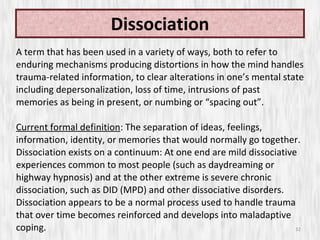

![Simple and Complex Trauma: Assessment and Treatment Kevin J. Drab, M.A., M.Ed., LPC, NBCCH, CAACD, CEMDRT Behavioral Counseling & Training, 418 Stump Road, Suite #208, Montgomeryville, PA 18936 Tel: (215) 527-2904 Fax: (215) 699-3382 e-mail: [email_address] web site: http://BCTPRO.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/simpleandcomplextrauma-1318200608817-phpapp02-111009175132-phpapp02/75/Simple-And-Complex-Trauma-1-2048.jpg)

![Short Screening Scale for PTSD In your life, have you ever had any experience that was so frightening, horrible, or upsetting that, in the past month , you... 1. Have had nightmares about it or thought about it when you did not want to? [ ] YES [ ] NO 2. Tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it? [ ] YES [ ] NO 3. Were constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled? [ ] YES [ ] NO 4. Felt numb or detached from others, activities, or your surroundings? [ ] YES [ ] NO](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/simpleandcomplextrauma-1318200608817-phpapp02-111009175132-phpapp02/85/Simple-And-Complex-Trauma-38-320.jpg)