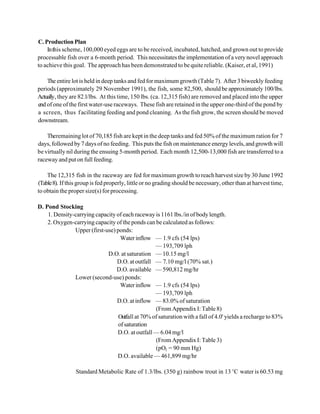

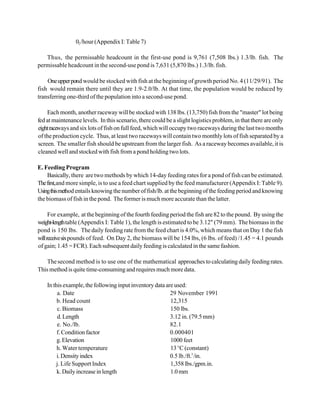

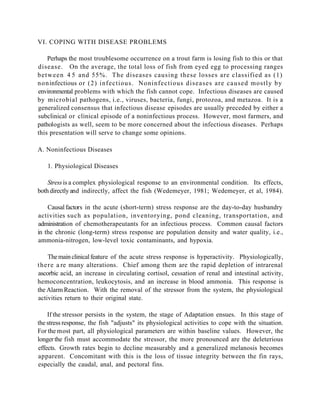

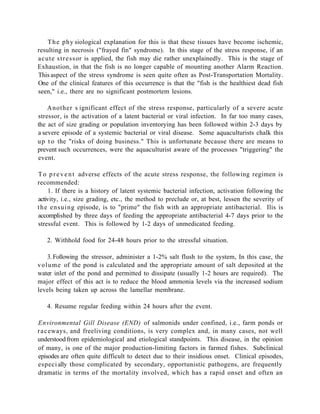

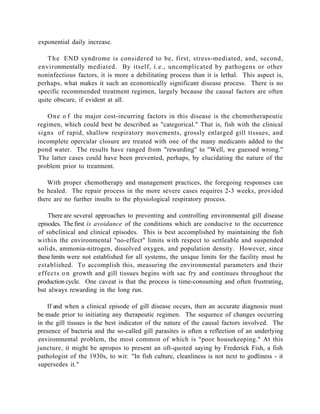

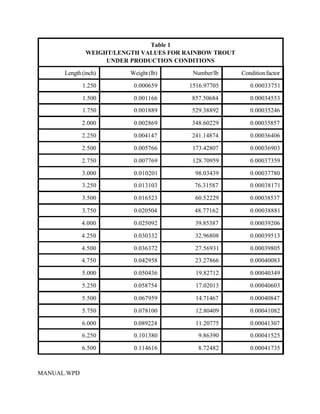

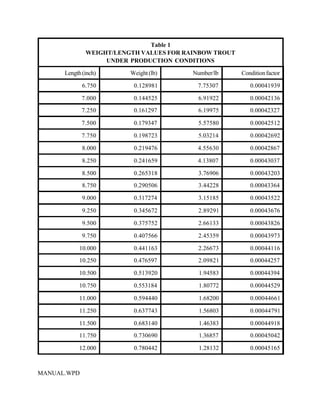

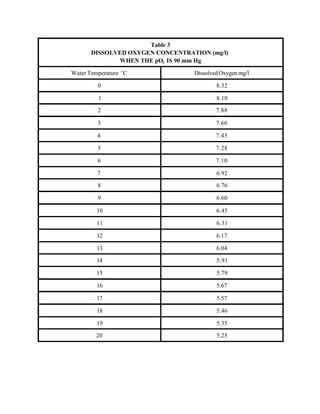

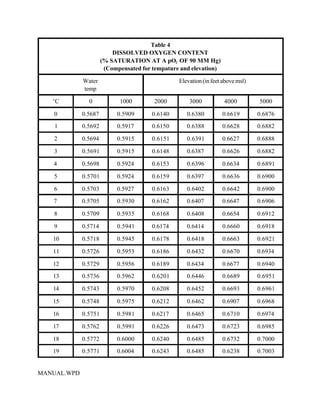

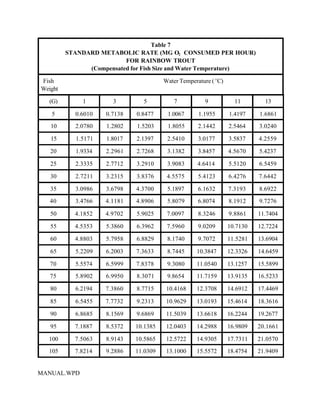

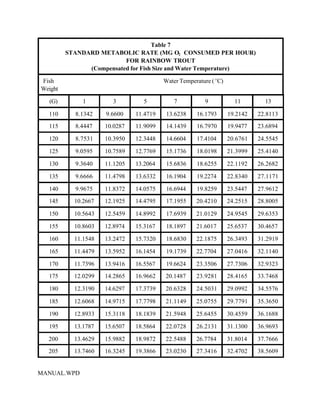

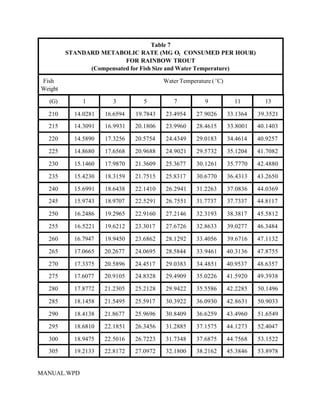

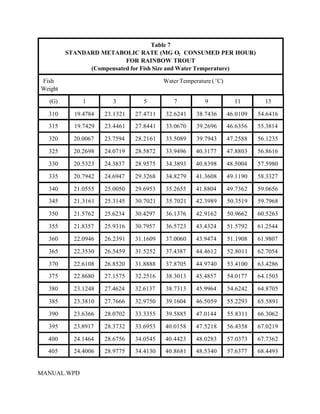

This document provides a manual for rainbow trout production on a family-owned farm. It discusses key factors that affect production, including fish-associated factors like stress response and nutritional requirements, water-associated factors like dissolved oxygen and ammonia levels, and management-associated factors like growth programming and disease prevention. The manual aims to help small trout farmers survive by achieving quality products delivered on time and in the required form through effective production planning and management.