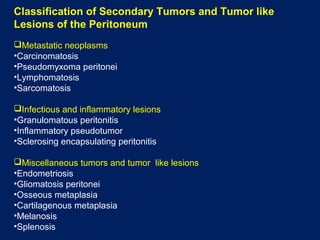

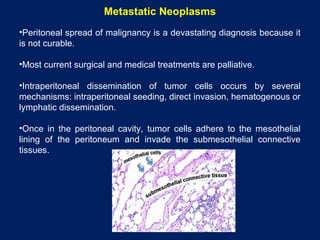

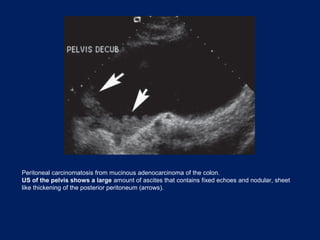

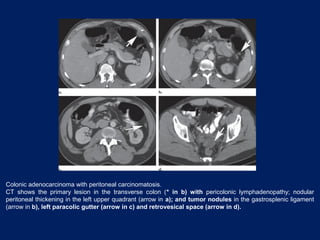

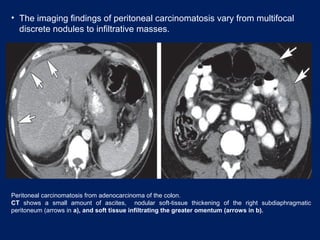

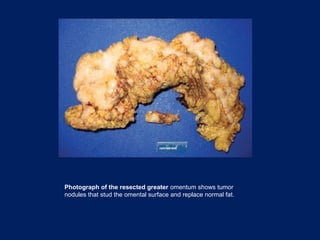

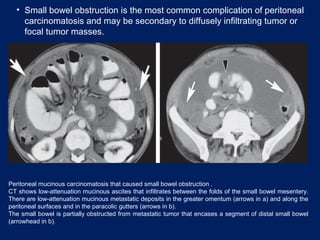

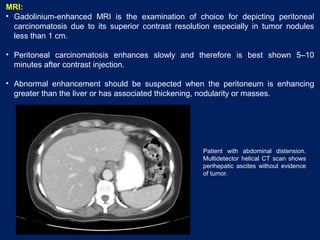

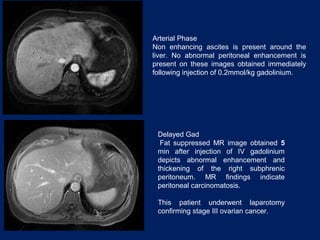

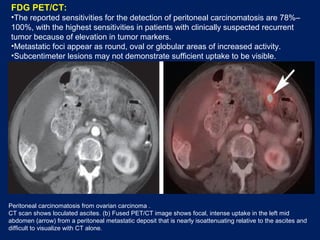

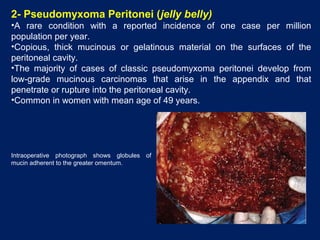

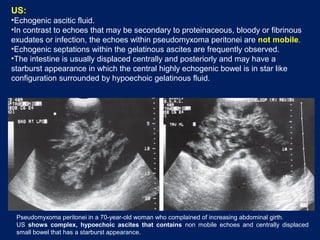

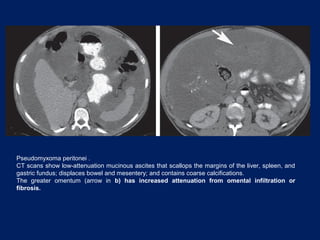

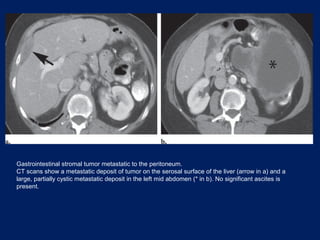

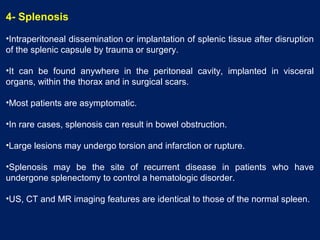

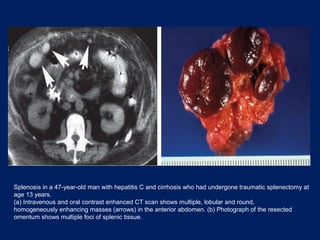

This document discusses secondary tumors and tumor-like lesions of the peritoneal cavity. It begins by introducing the three broad categories of pathologies that can affect the peritoneum - metastatic neoplasms, infectious/inflammatory lesions, and miscellaneous tumors. It then focuses on metastatic neoplasms, describing carcinomatosis, pseudomyxoma peritonei, lymphomatosis, and sarcomatosis in 1-3 sentences each. Imaging features are provided for each condition. The document emphasizes the importance of identifying subtle lesions on imaging for staging and treatment planning.