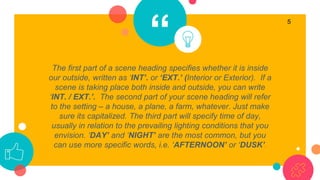

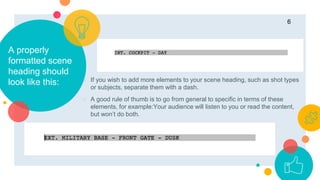

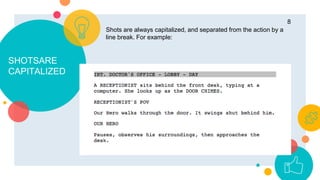

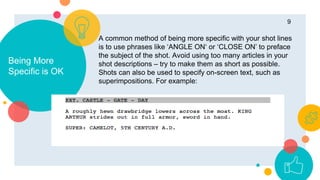

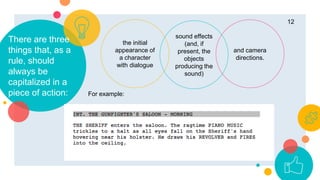

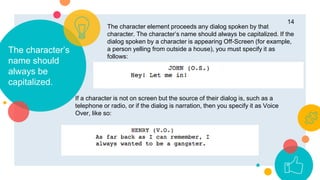

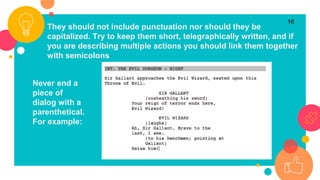

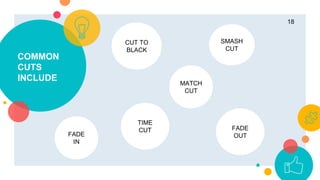

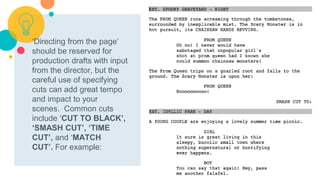

This document provides information and guidelines about screenplay formatting for professional scripts. It discusses the strict formatting standards that scripts adhere to and how Celtx can be used to help follow these standards. The key elements that are covered include scene headings, shots, character names, action, dialogue, transitions, and other formatting rules. Specific examples are provided to illustrate proper formatting for each element. The goal of screenplay formatting is to clearly convey all necessary information about how a scene will be shot and to make the story easy to understand.