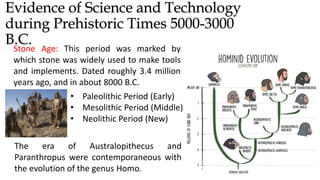

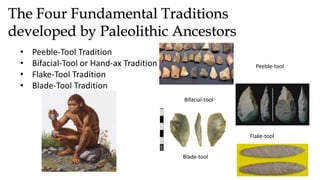

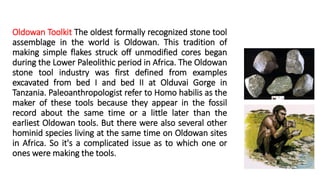

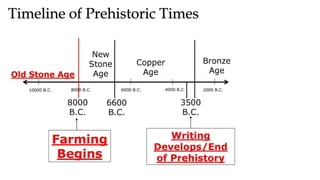

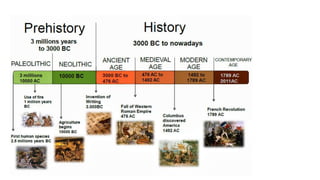

This document provides an overview of science and technology development during prehistoric times from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. It describes how early humans discovered tools like stone tools during different Stone Age periods (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the four fundamental stone tool traditions that developed. It then discusses the Oldowan, Acheulean, Mousterian, Aurignacian, microlithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age tool technologies and how tools evolved over time from basic stone tools to the use of copper, bronze and eventually iron.