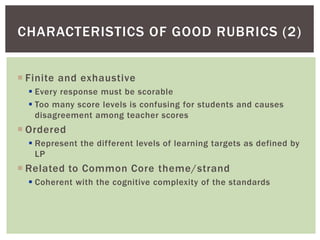

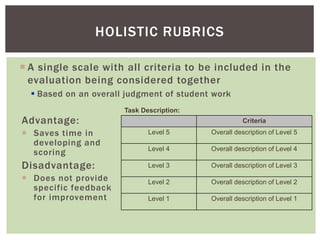

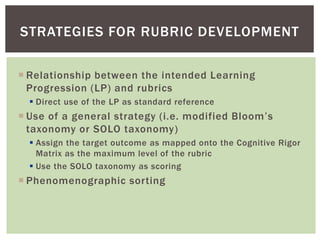

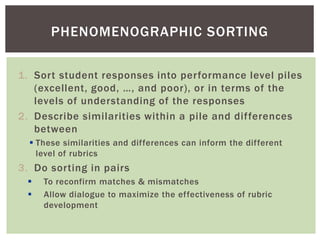

This document provides information on rubric development including definitions, characteristics of good rubrics, types of rubrics, and strategies for creating rubrics. It defines rubrics as scoring tools that lay out expectations for assessments. Good rubrics are well-defined, context-specific, finite, ordered, and related to learning standards. Rubrics can be analytic (describing each criterion) or holistic (providing an overall score). Strategies for developing rubrics include reflecting on tasks and standards, listing outcomes, grouping criteria, and choosing a format. The document also discusses using rubrics with students to clarify expectations.