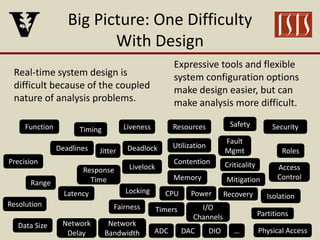

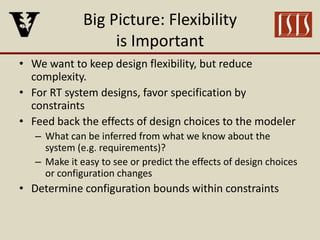

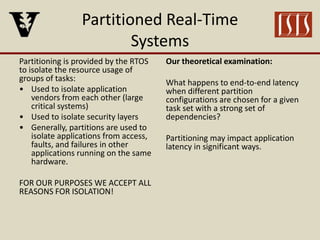

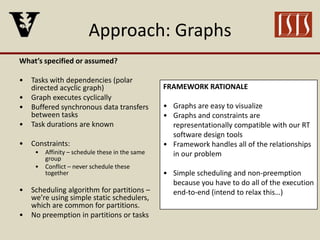

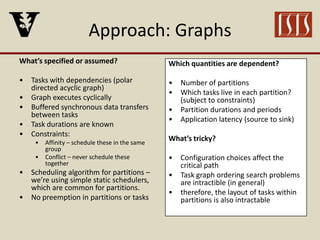

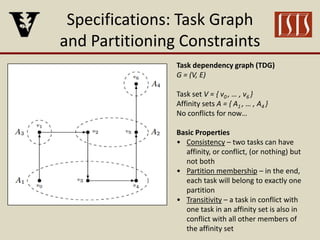

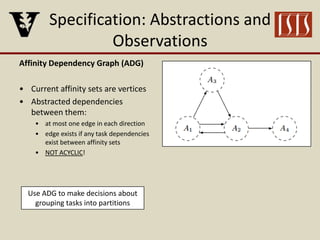

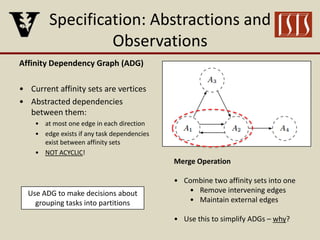

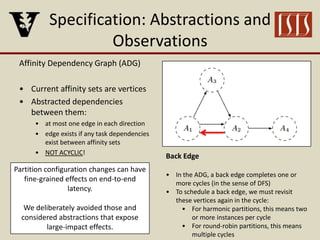

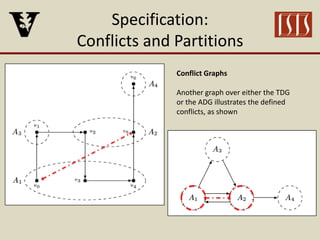

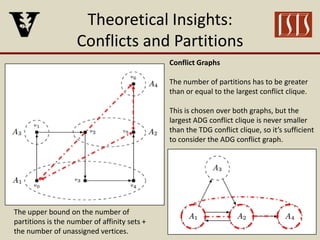

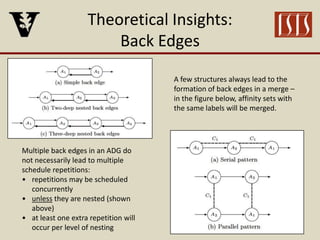

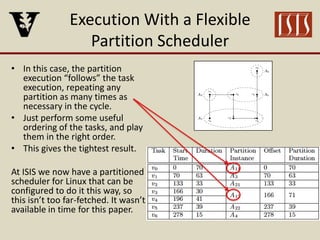

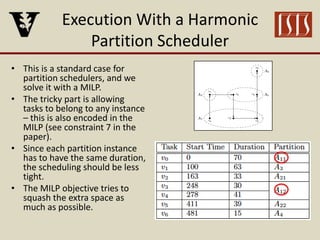

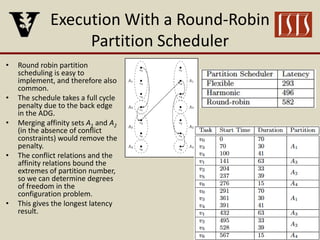

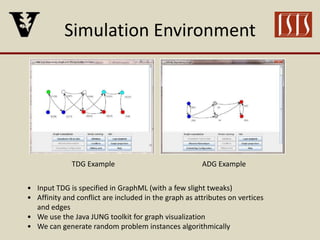

The document discusses partition configuration for real-time systems, highlighting the complexities of design due to task dependencies and resource management. It introduces a framework based on graphs to analyze the impact of different partition configurations on end-to-end latency, emphasizing the importance of isolation and scheduling in real-time systems. Theoretical insights and practical implications for scheduling algorithms and the analysis of task graphs are also presented, along with future work directions.