The document discusses a roundtable event focused on the complexities of multilingual research, especially in contexts involving communities, refugees, and migration. It highlights the ethical implications, language choices, and methods necessary for effectively conducting research in multilingual settings, while emphasizing the importance of trust and ethical sensitivity among researchers. Key insights include the challenges of transcription, the necessity for flexible language use, and the need for researchers to be aware of their own linguistic resources and the implications of their research practices.

![Challenges in the current context

• Sets of principles & codes of ethics => “illogical” and “stale” are adopted

by professional and academic associations to ensure “value-free” social

science (Christians, 2011, p. 66).

• Constraints on multilingual research practice vary across institutions,

across fields of research, disciplines and paradigms.

• The symbolic & regulatory power of institutions [e.g., governmental,

educational] . . . is not fixed or monolithic: it is always possible to create

spaces for alternative ways of working and for different voices to be

heard.

• Creating these spaces depends on the agency of individual researchers . . .

and principal investigators on research projects.

(Andrews & Martin-Jones, 2012)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wpltyscbtg2ukghaccxh-signature-8db08d190ad79f355703b3244216ff10f5ea24d3b6570754ffdb785402d05fbb-poli-151217152952/75/RMTC-Hub-Presentation-P-Holmes-5-2048.jpg)

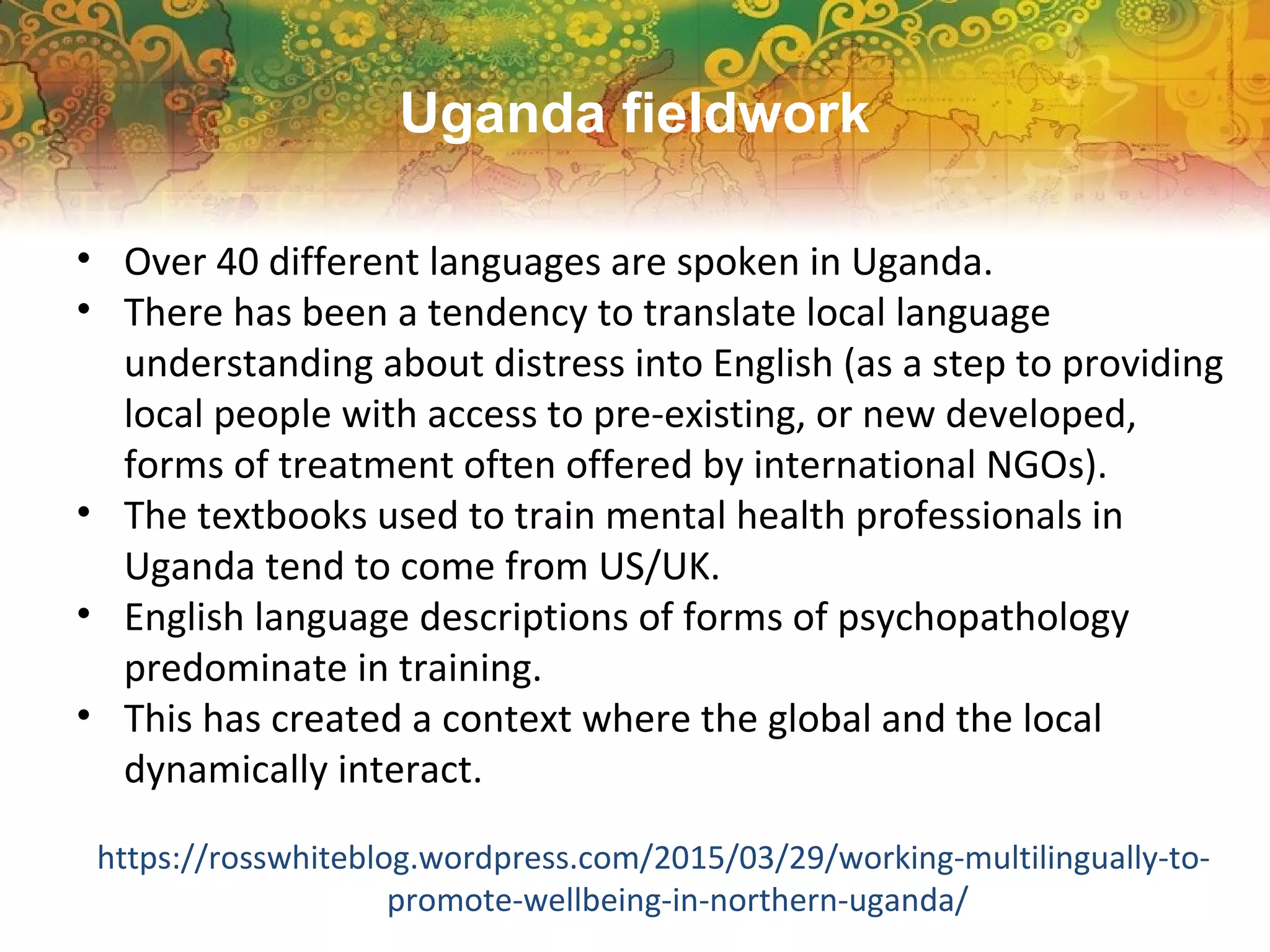

![• Ross’ Blog: “It is important to note that the school that we visited

yesterday and the University we visited today only teach students using

English. This highlights the challenges that health professionals might

have [having been] taught in a language that is not necessarily the first

language of the people that they subsequently treat. I think this serves

to highlight the ecological validity and potential utility of the research

that we are conducting.”

• “Discussions with both Richard and Katja have also allowed me to reflect

critically on the methodology that we have been employing and

sharpened my awareness around the points in the process where the

use of English language training has juxtaposed with the use of Lango in

the delivery of interviews and the recording of associated information. I

also have to concede that having Richard and Katja in the team has

increased the amount of Lango that I have been able to pick up.”

https://rosswhiteblog.wordpress.com/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wpltyscbtg2ukghaccxh-signature-8db08d190ad79f355703b3244216ff10f5ea24d3b6570754ffdb785402d05fbb-poli-151217152952/75/RMTC-Hub-Presentation-P-Holmes-14-2048.jpg)