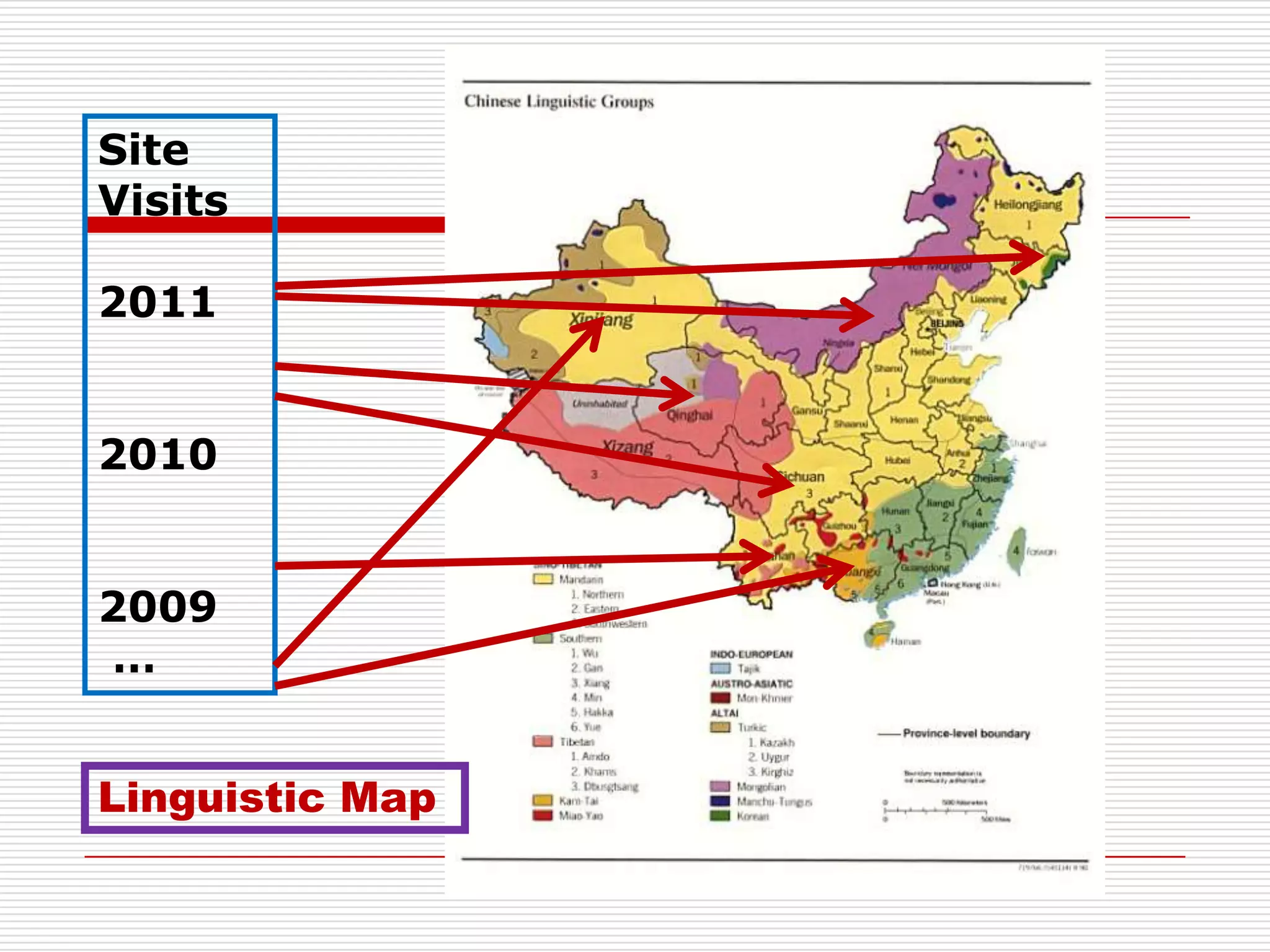

This document discusses the challenges of conducting research in multilingual communities and presents three case studies of researchers working in China. It notes the paradigm shift in research from positivism to interpretivism due to the dynamics of language and culture. The case studies describe researchers with varying levels of language competence and their experiences dealing with translation, validity, rapport building, and other issues. While each researcher faces difficulties, they have all produced prominent work on trilingualism in China. The document suggests there is no single most effective approach and researchers must find ways to balance accuracy with local complexities.