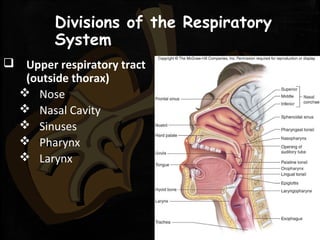

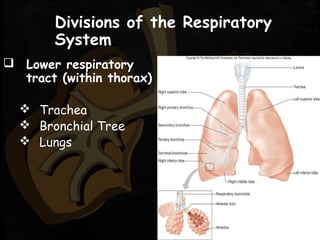

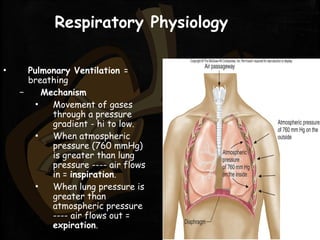

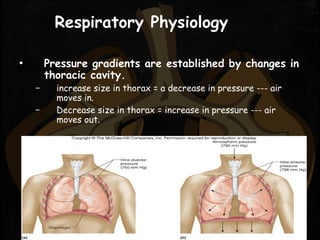

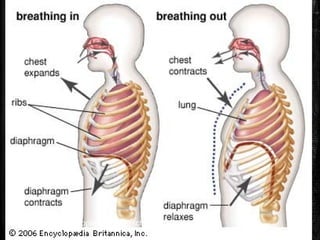

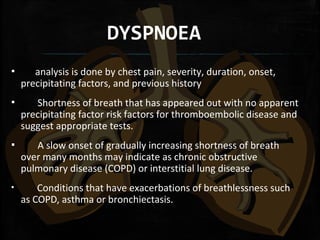

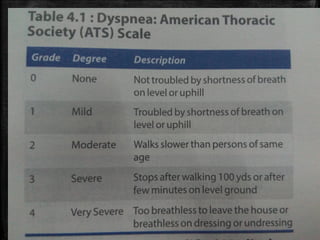

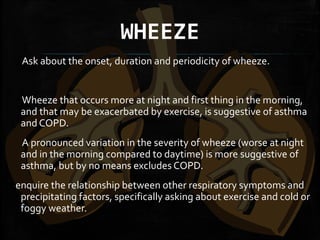

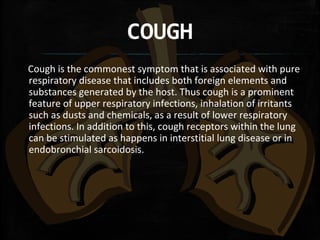

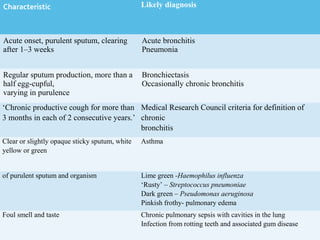

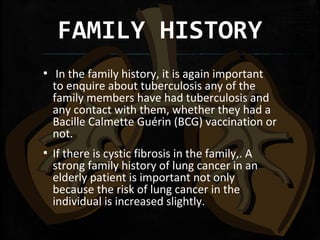

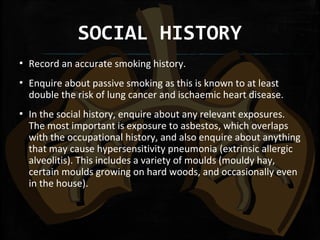

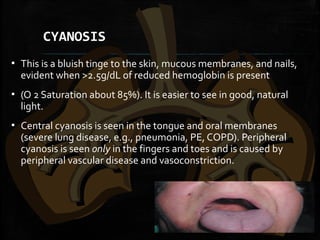

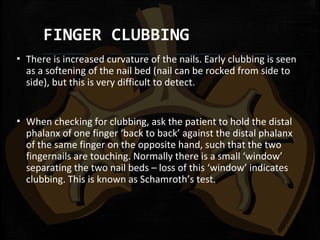

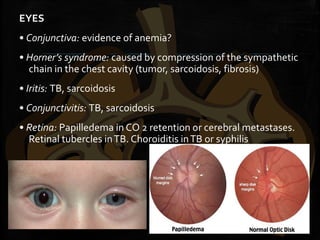

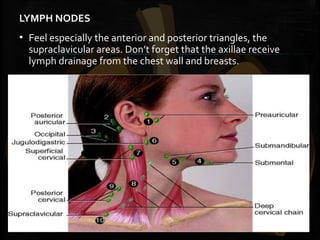

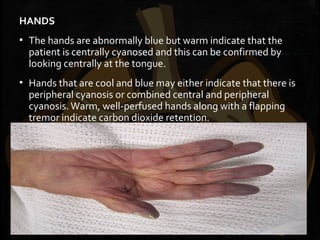

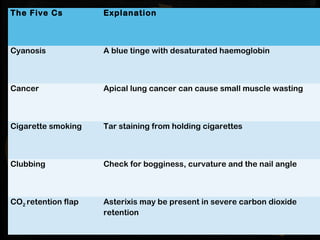

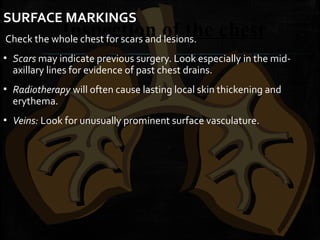

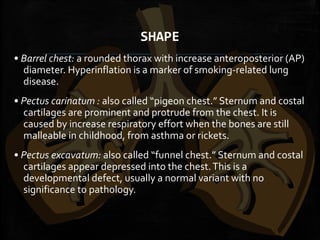

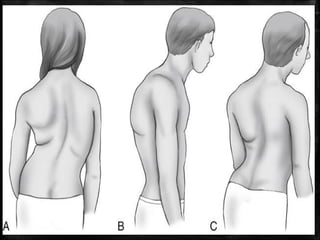

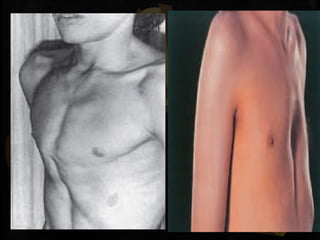

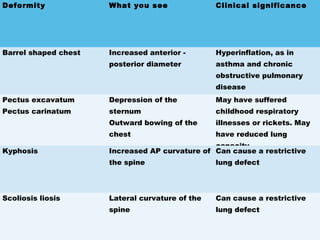

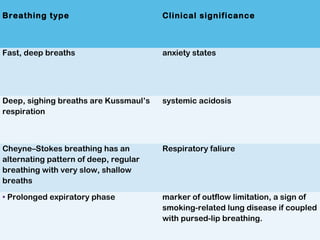

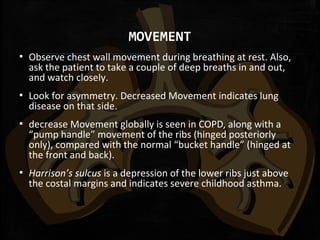

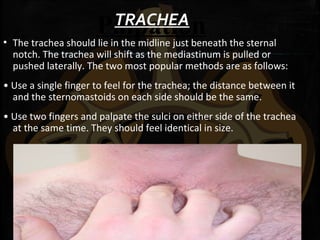

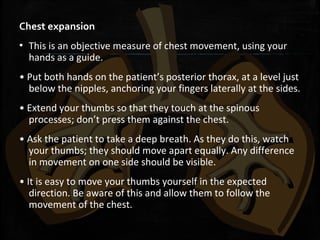

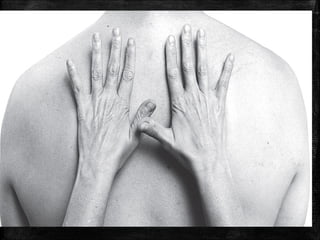

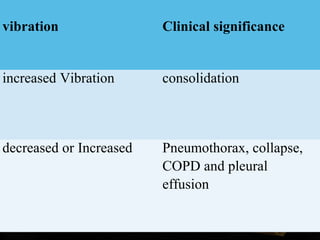

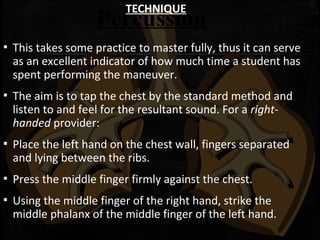

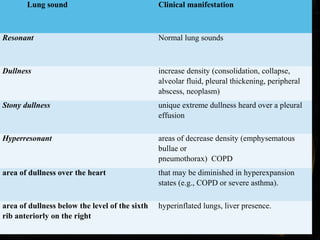

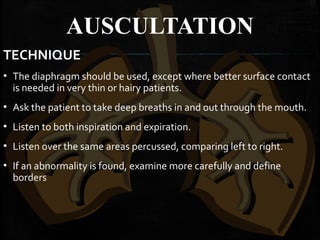

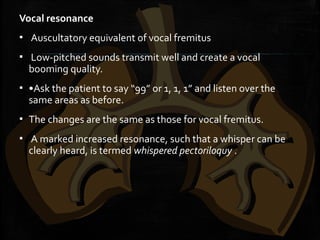

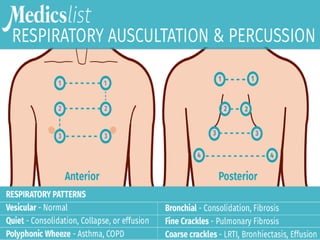

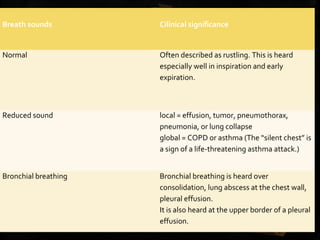

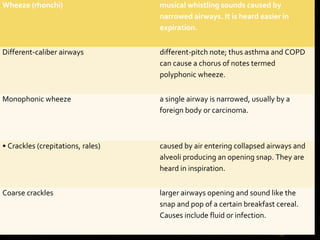

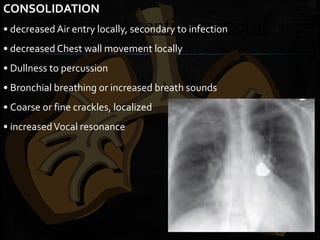

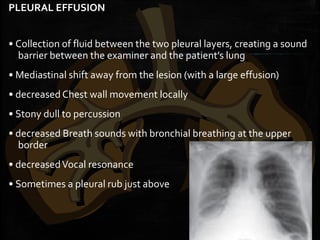

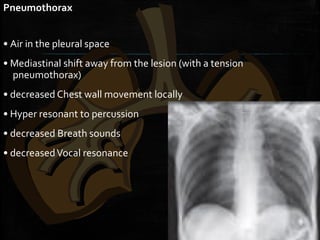

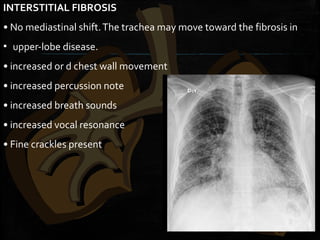

The document provides information on assessing the respiratory system through history and physical examination. It describes the key symptoms of respiratory disease including chest pain, dyspnea, cough, wheeze, sputum production, and hemoptysis. It outlines how to evaluate these symptoms and what they may indicate. It also details the physical examination of the respiratory system, covering inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation of the chest and other relevant body systems. The document is a guide for comprehensively assessing the respiratory system in clinical practice.