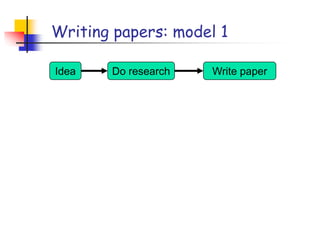

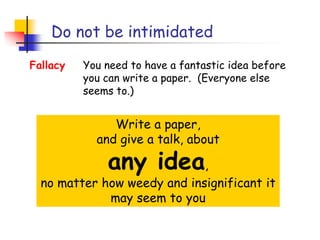

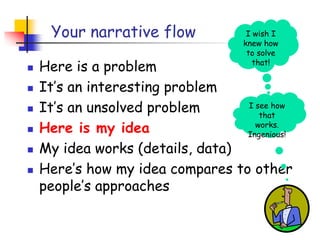

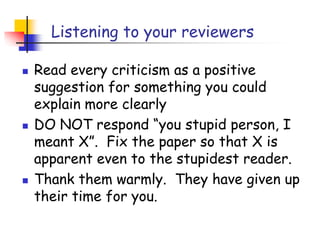

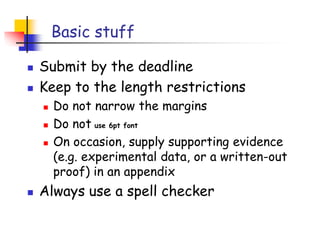

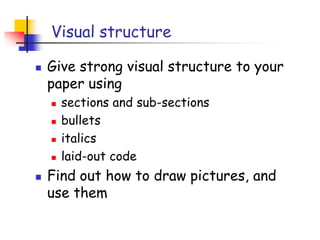

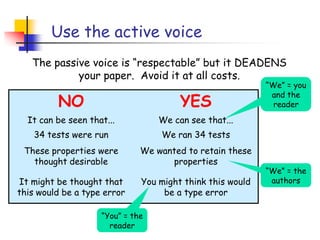

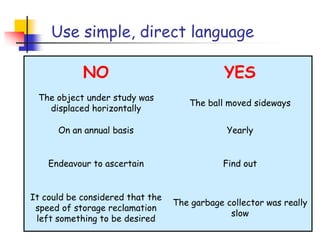

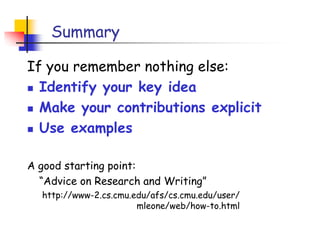

The document provides guidance on writing an effective research paper, emphasizing the importance of clear communication and the development of ideas through writing. Key points include the necessity to identify a single, clear idea, maintain a narrative flow, and be open to criticism from reviewers. Additionally, it offers practical advice on writing style, structure, and the importance of starting early in the writing process.