This document provides guidance on developing the central argument and thesis statement for an academic journal article. It discusses the differences between a thesis and journal article in terms of length, scope, focus and target readership. The main points are:

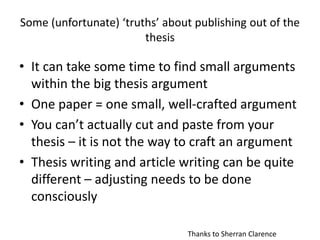

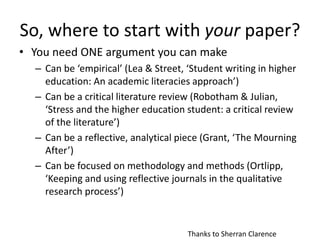

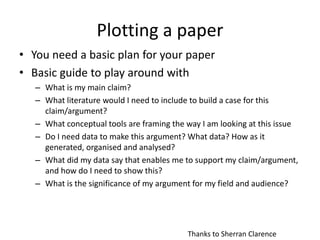

1) A journal article needs to focus on one clear, evidence-based argument that can be summarized concisely, unlike a thesis which explores arguments in more depth.

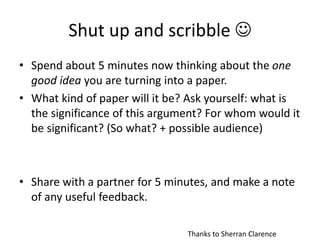

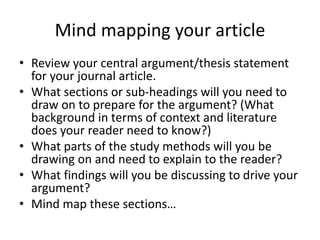

2) Developing the thesis statement involves mind-mapping the key terms and structure of the article to identify the central argument.

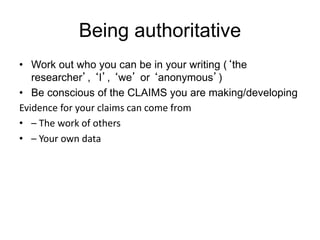

3) The argument must be substantiated with examples from literature and any data collected, while acknowledging alternative perspectives and positioning the work within the relevant academic community.