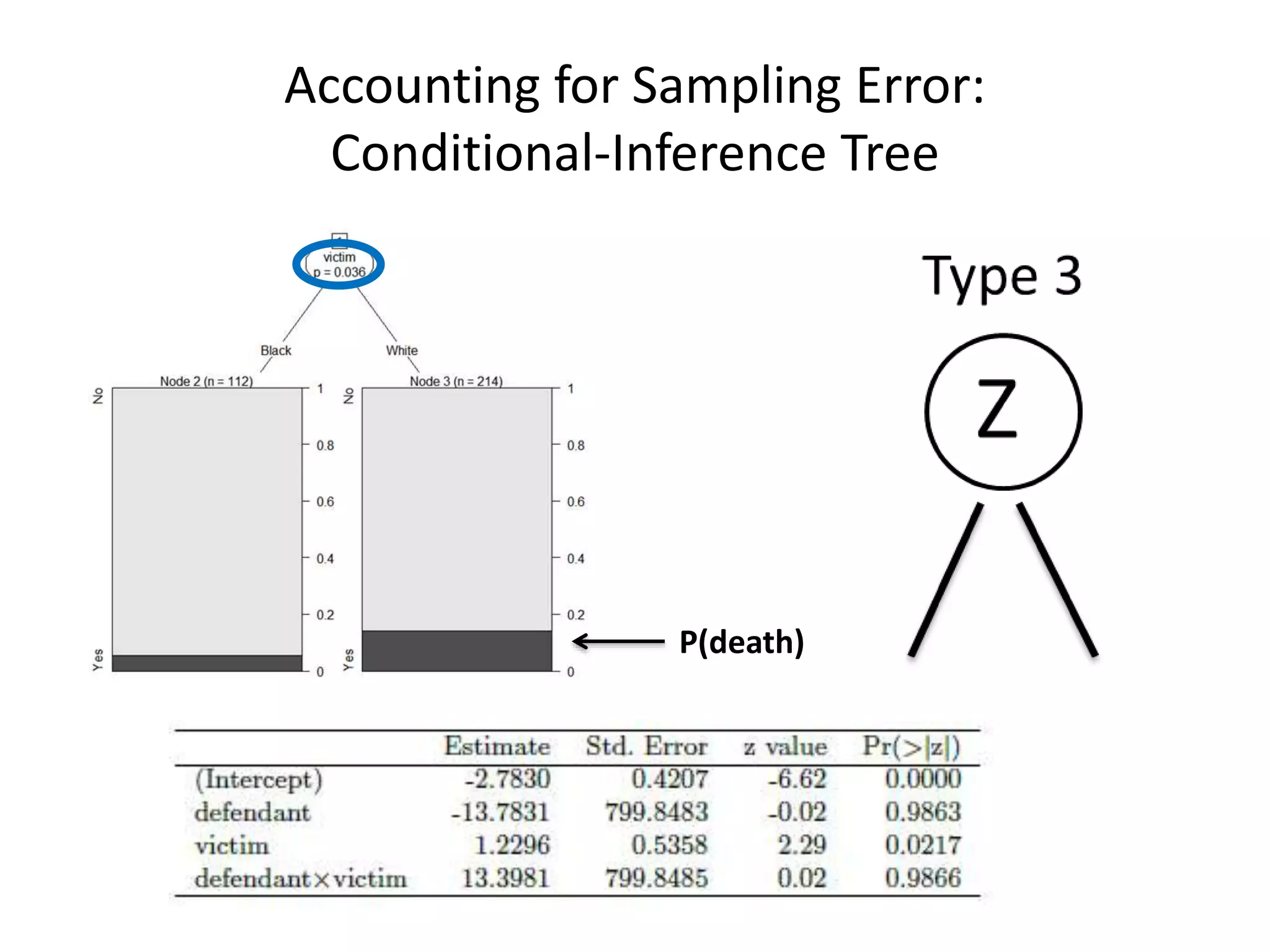

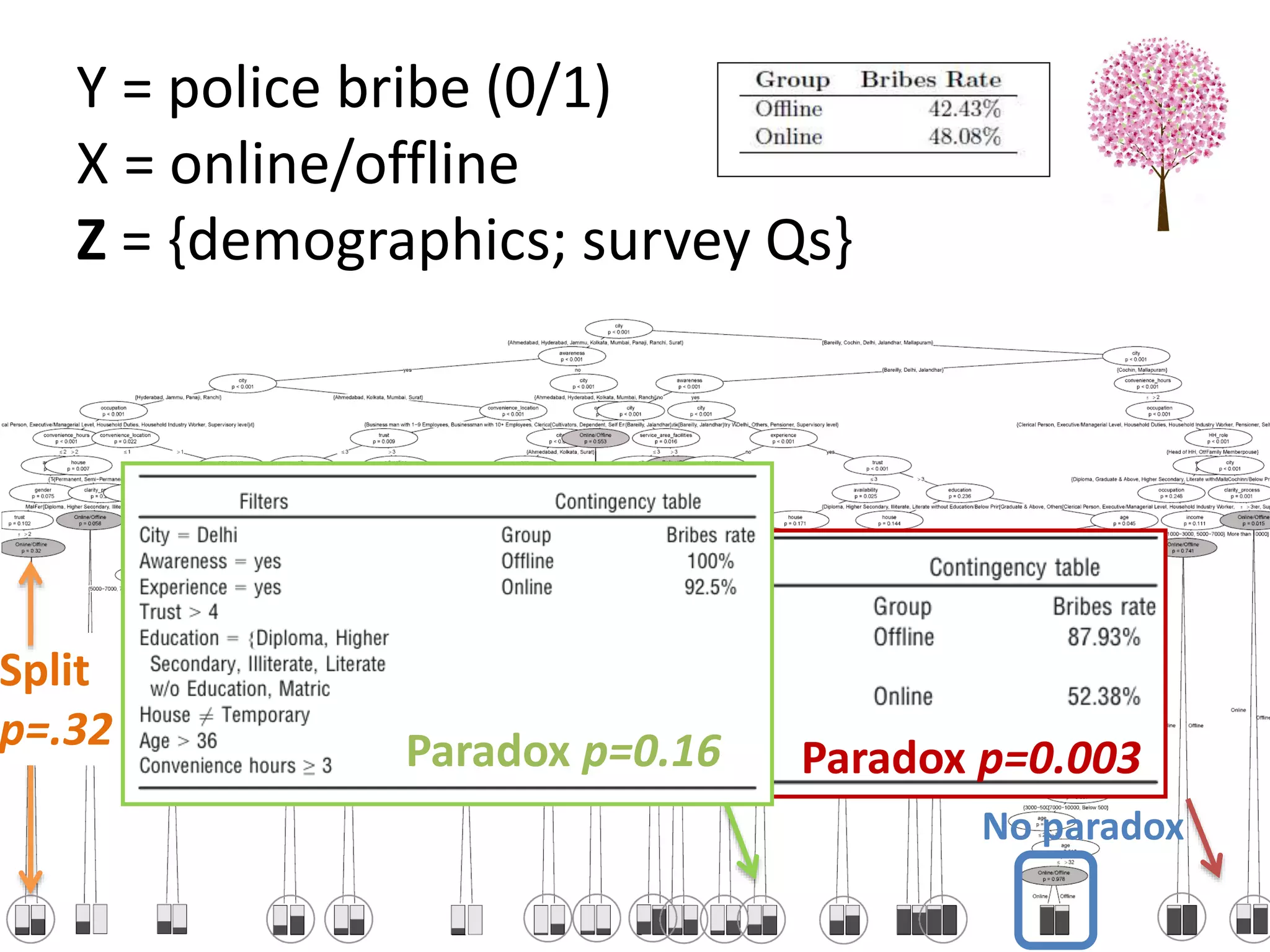

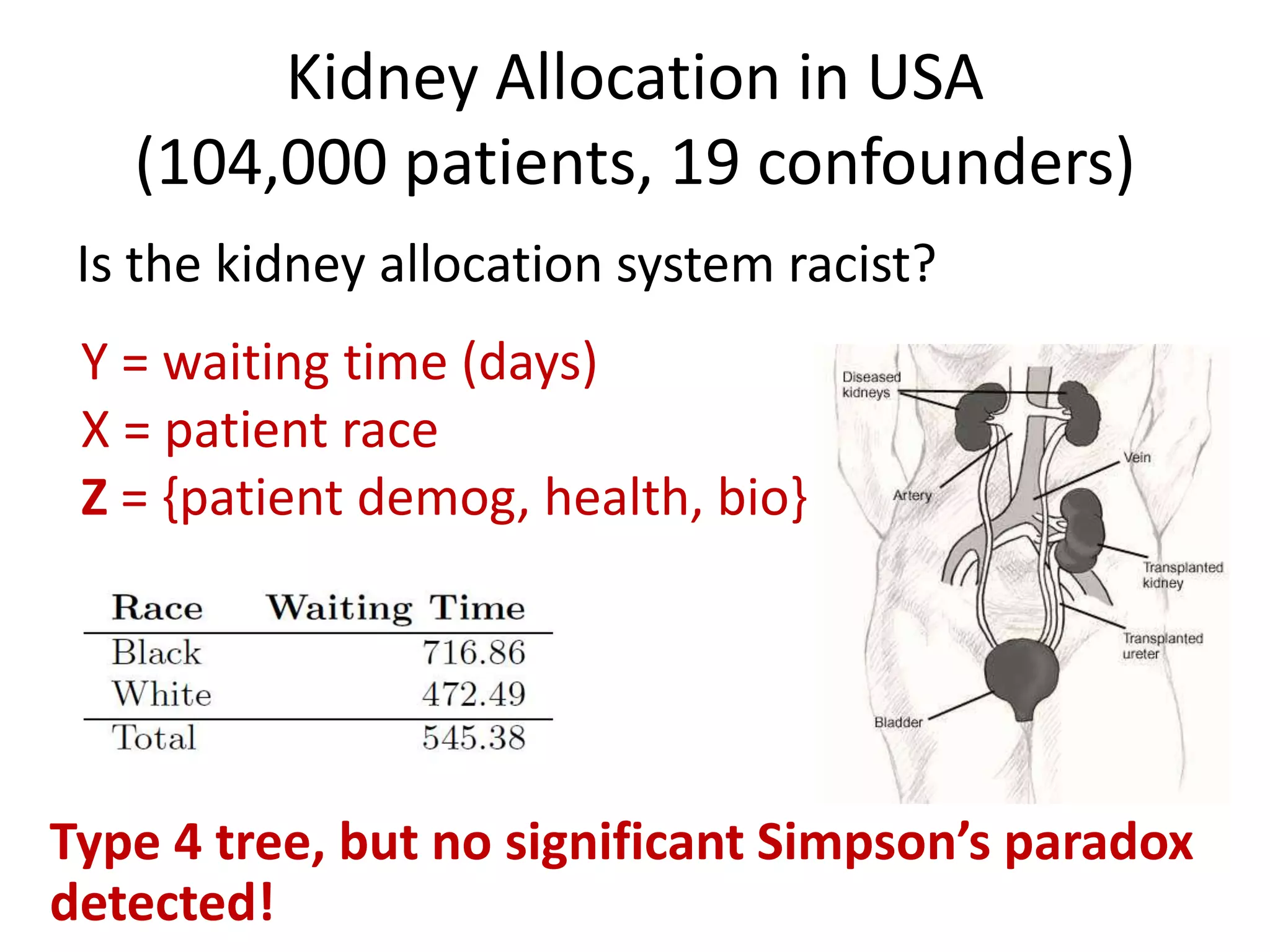

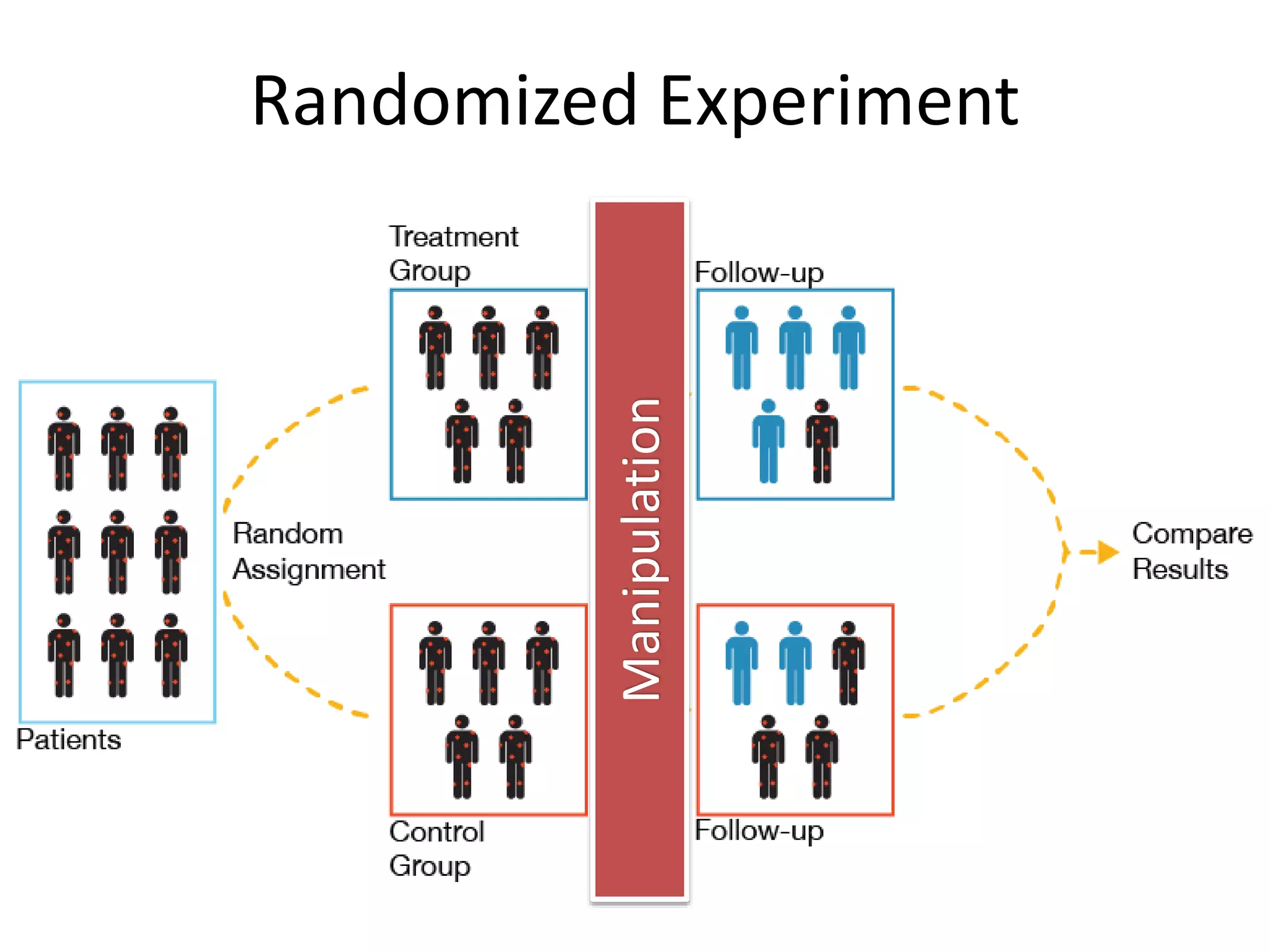

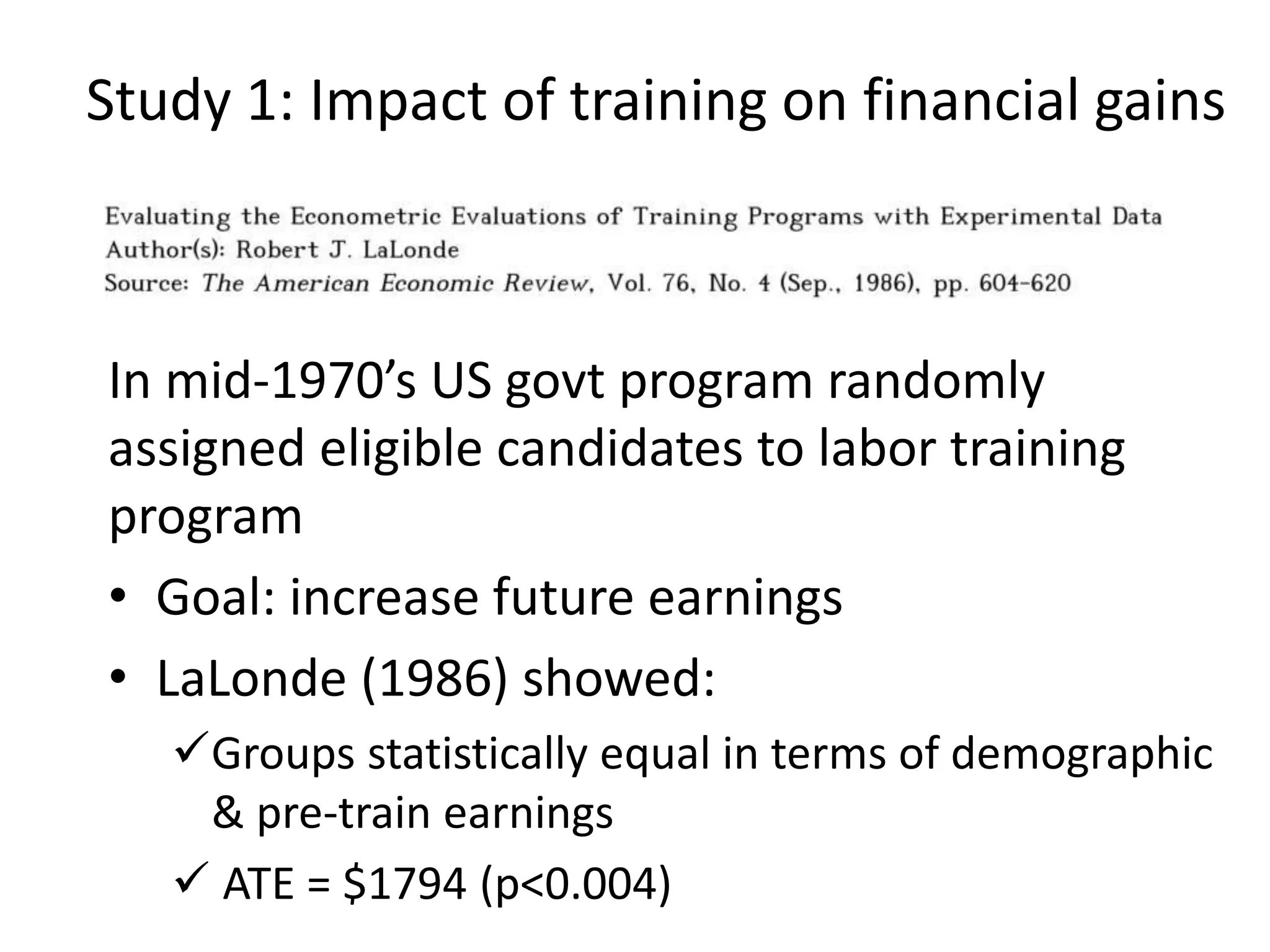

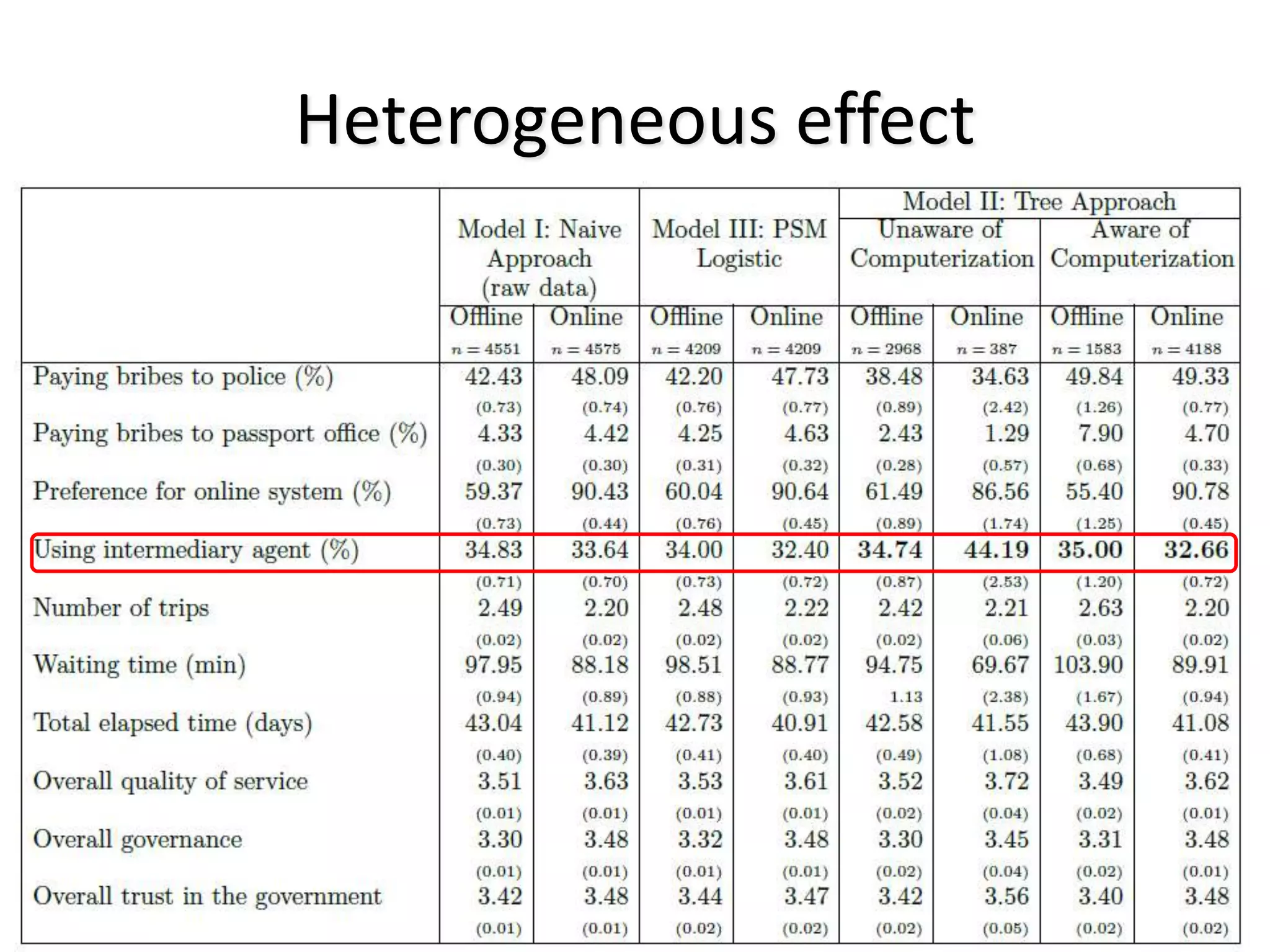

The document discusses a tree-based approach for addressing self-selection in causal research involving high-dimensional data, aimed at improving impact studies such as randomized experiments and quasi-experiments. It outlines the challenges of traditional propensity score methods in big data and proposes a new method that leverages classification and regression trees to identify confounders and analyze treatment effects more effectively. The authors present applications of this method in various domains, demonstrating its advantages over conventional techniques in detecting heterogeneous treatment effects and handling unbalanced covariates.

![Tree-Based Approach

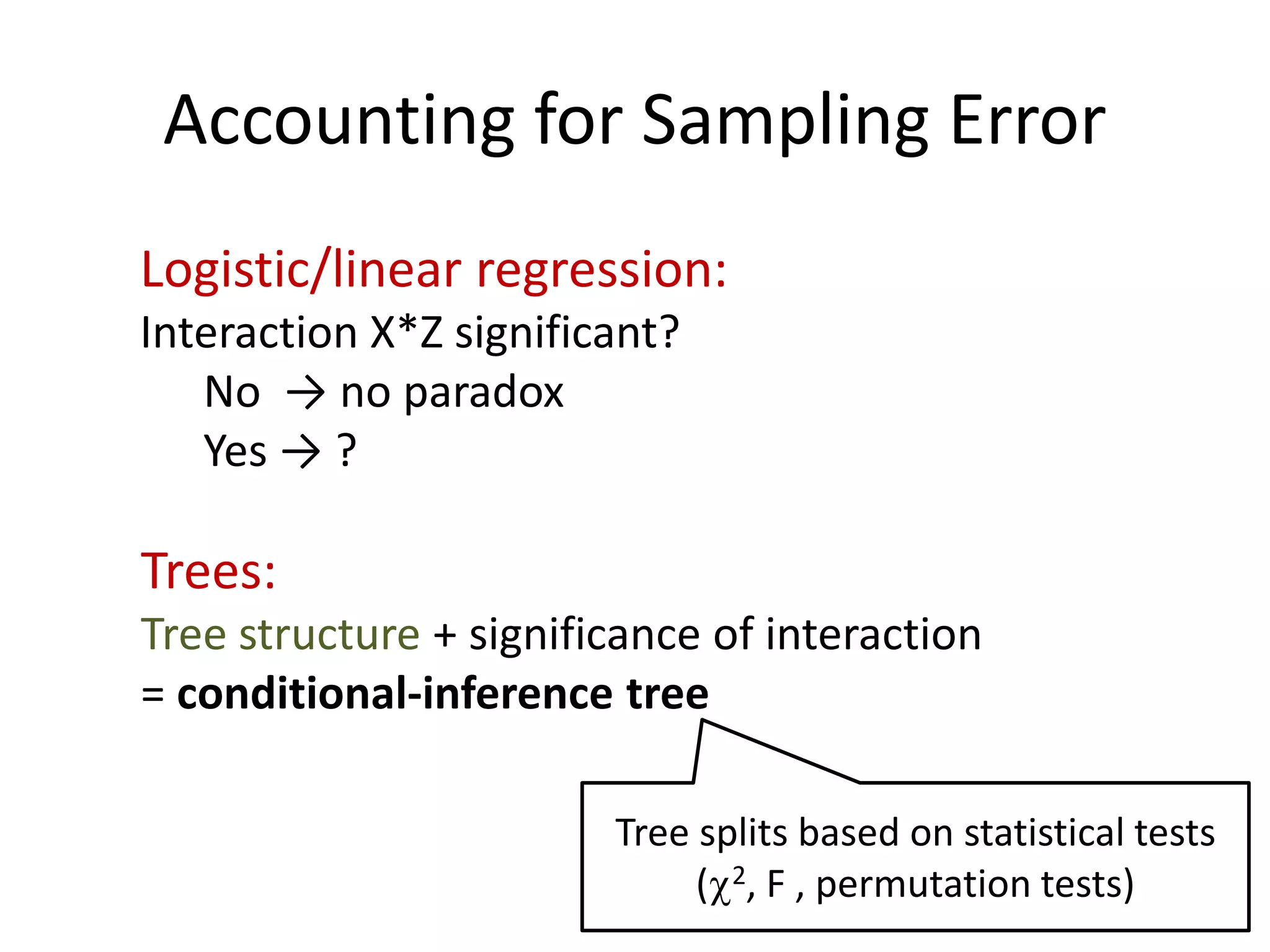

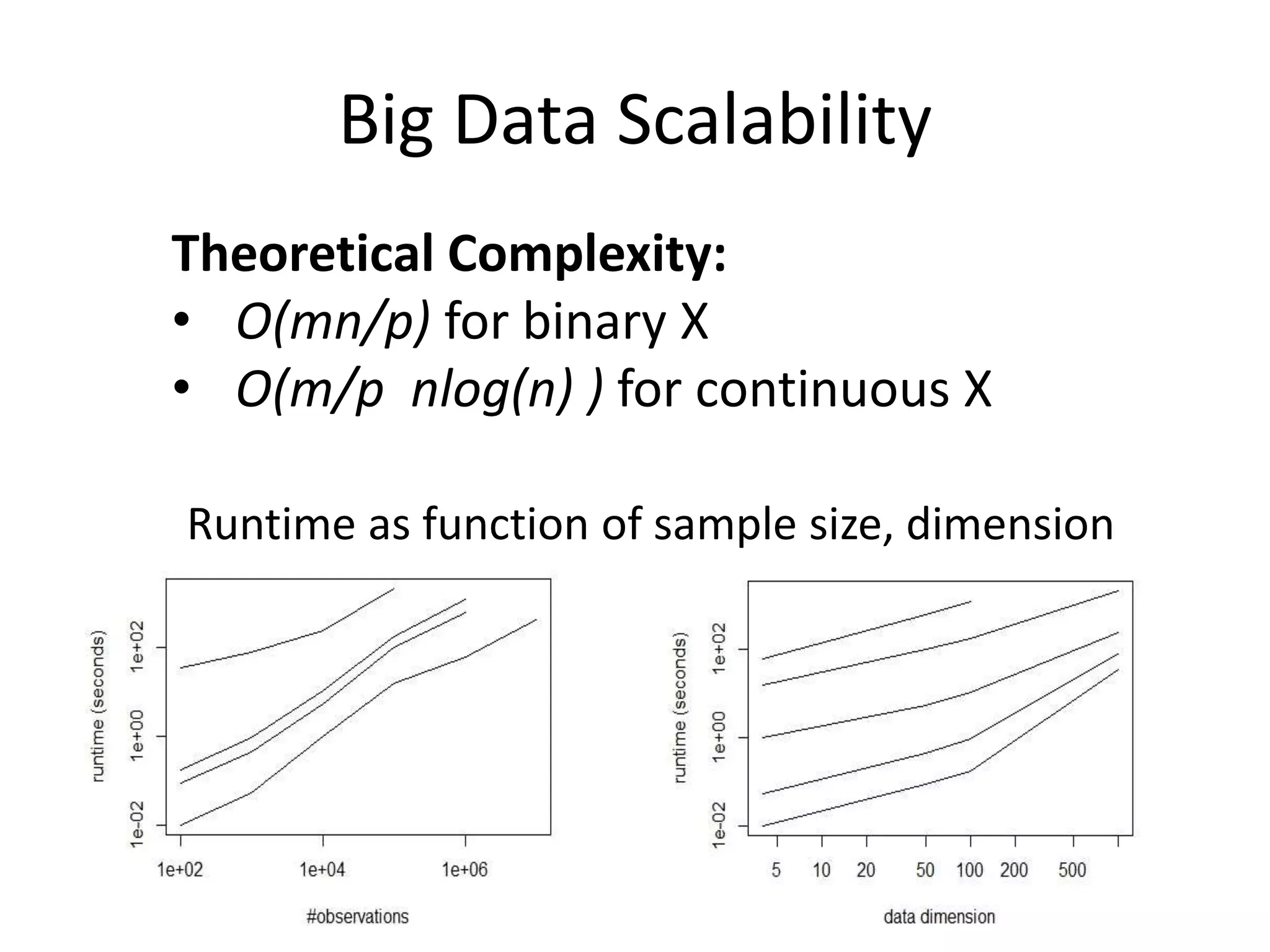

Four steps:

1. Run selection model: fit tree T = f(X)

2. Visualize tree; see unbalanced X’s

3. Treat each terminal node as sub-sample;

conduct terminal-node-level performance

analysis

4. Present terminal-node-analyses visually

5. [optional]: combine analyses from nodes with

homogeneous effects

Like PS, assumes observable self-selection](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/treesforcausalresearchwombatmonashnov2019-191129032230/75/Repurposing-Classification-Regression-Trees-for-Causal-Research-with-High-Dimensional-Data-12-2048.jpg)

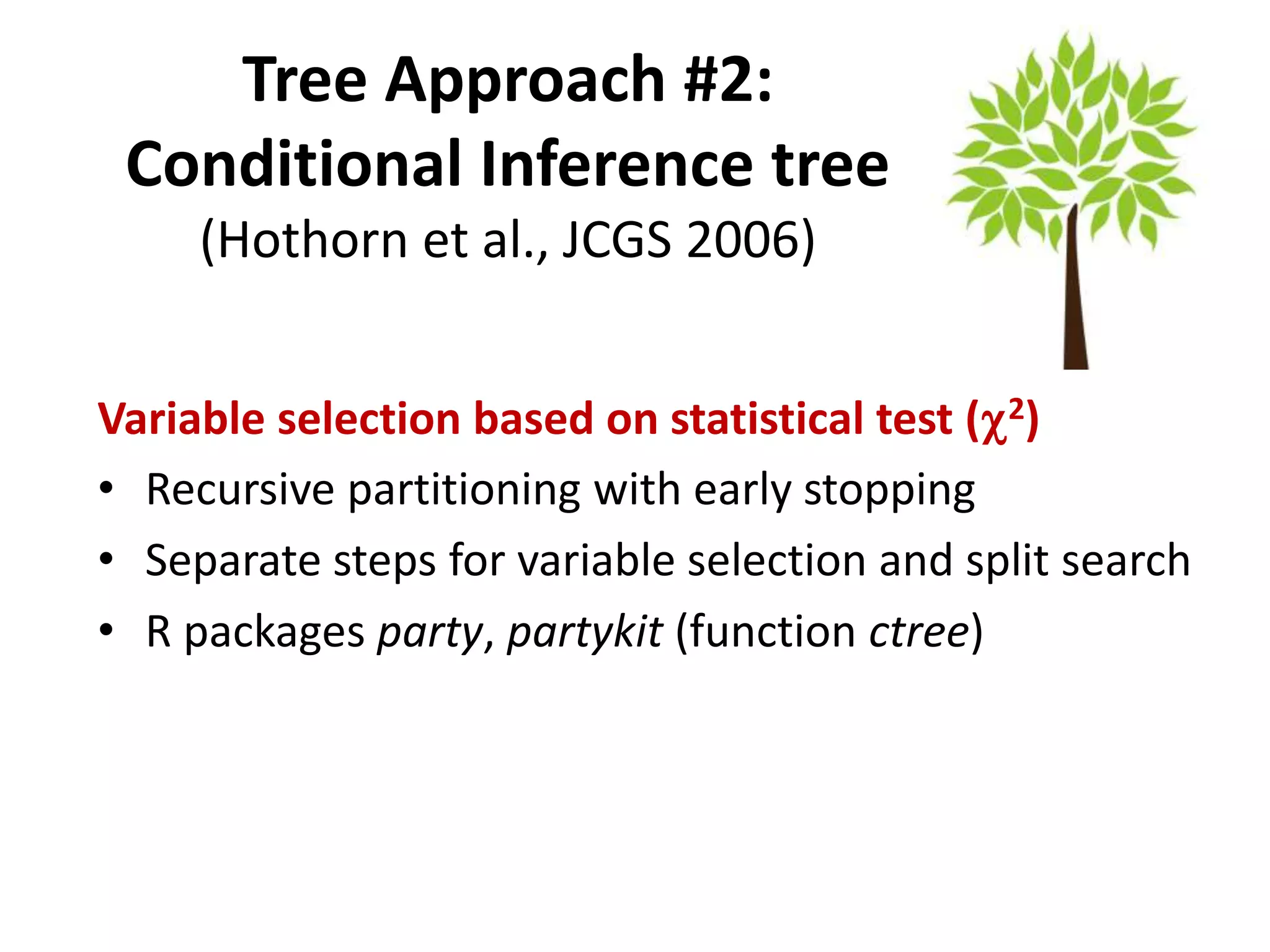

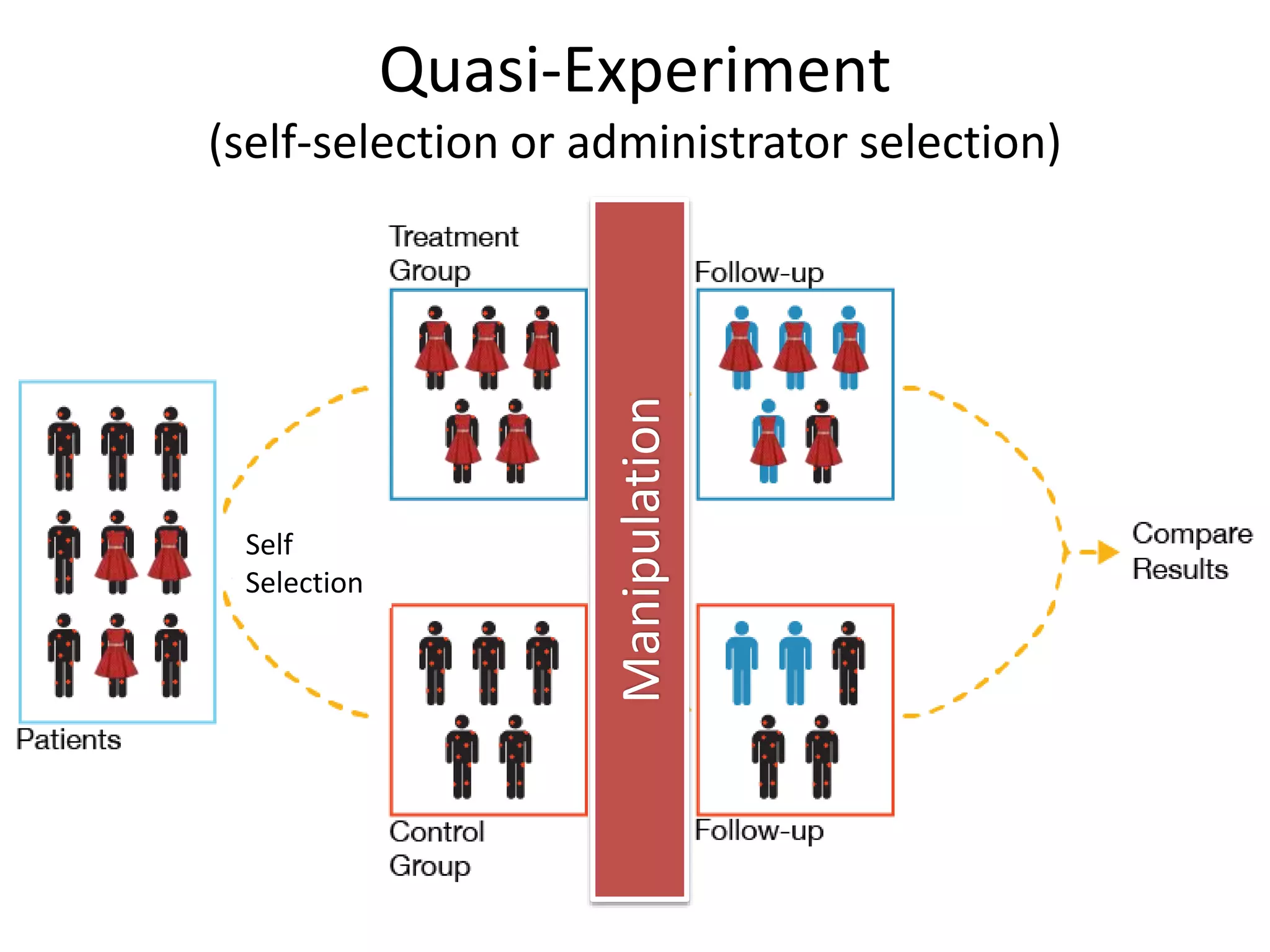

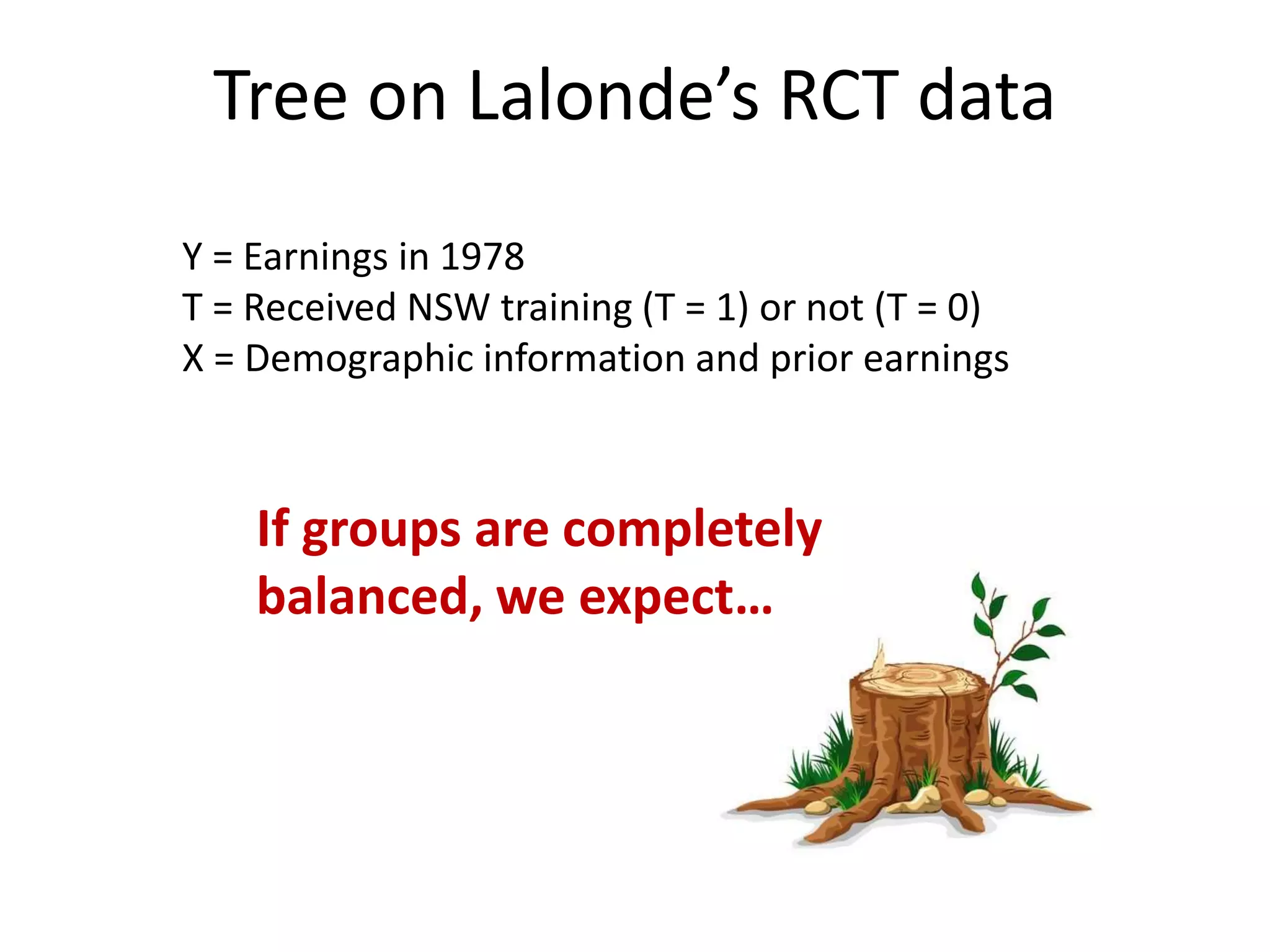

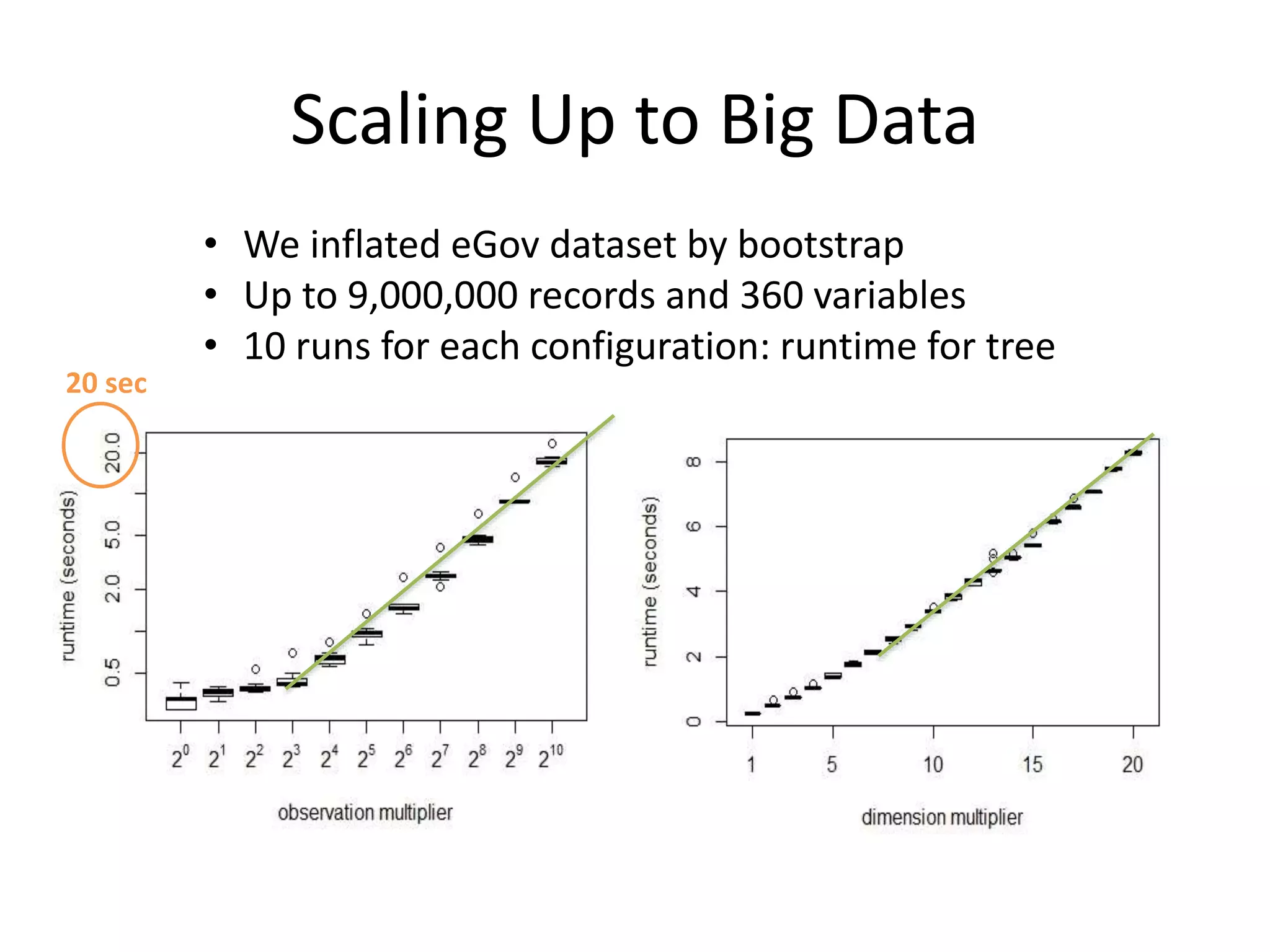

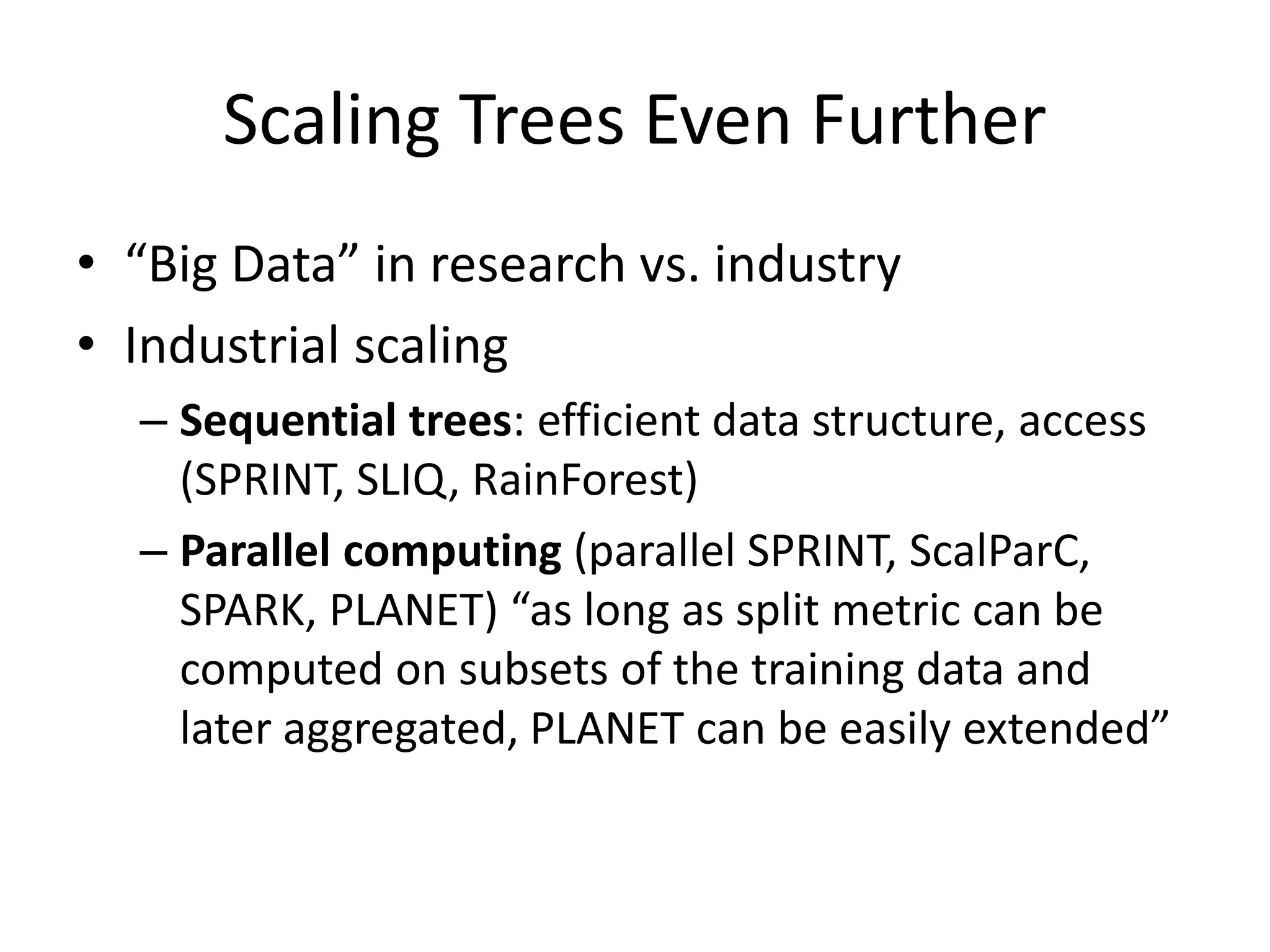

![Labor Training effect:

Observational control group

• LaLonde also compared with observational

control groups (PSID, CPS)

– experimental training group vs. obs control

– showed training effect not estimated correctly with

structural equations

• Dehejia & Wahba (1999,2002) re-analyzed CPS

control group (n=15,991), using PSM

– Effects in range [$1122, $1681], depends on settings

– “Best” setting effect: $1360

– Uses only 119 control group members (out of 15,991)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/treesforcausalresearchwombatmonashnov2019-191129032230/75/Repurposing-Classification-Regression-Trees-for-Causal-Research-with-High-Dimensional-Data-17-2048.jpg)

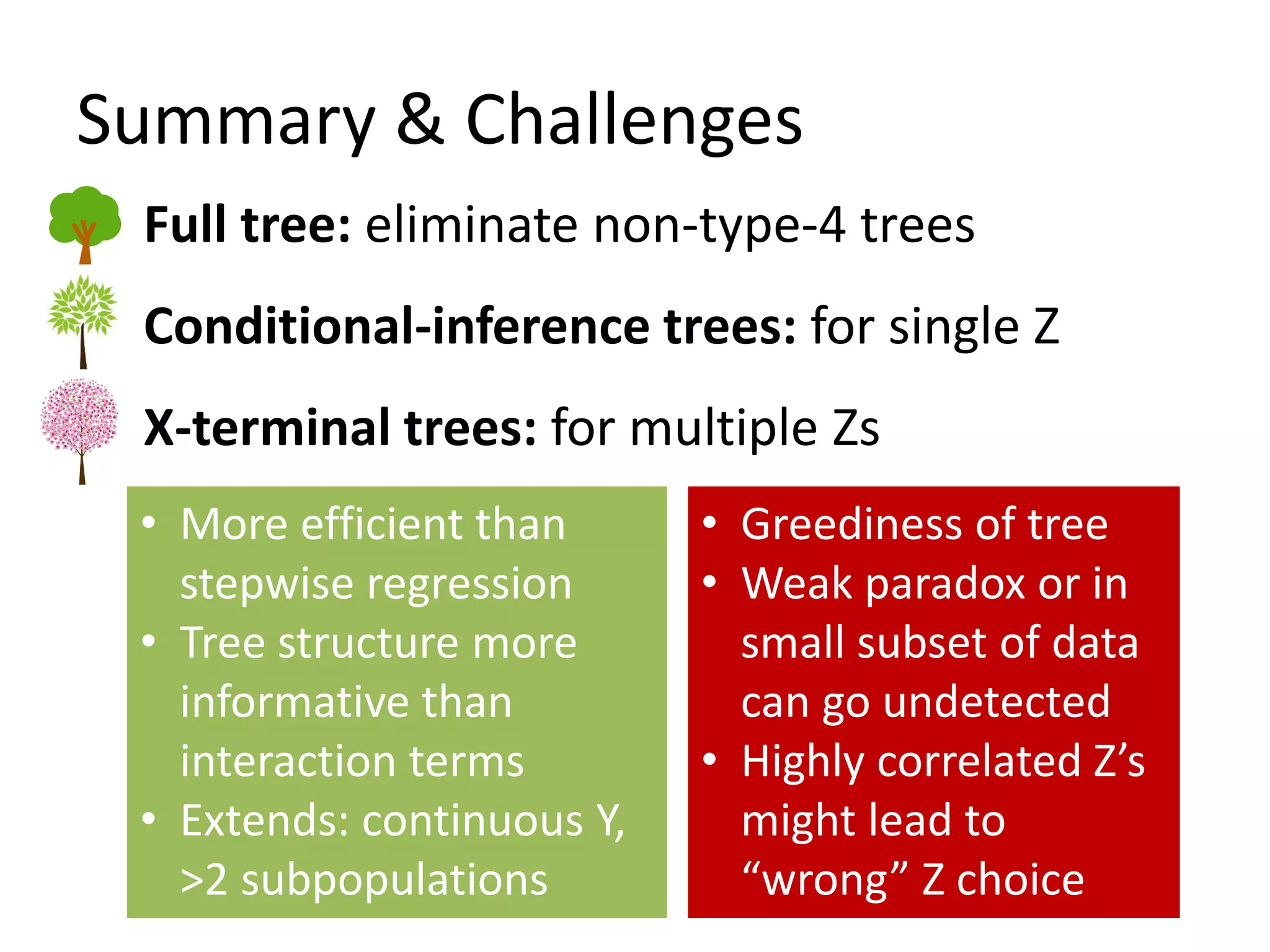

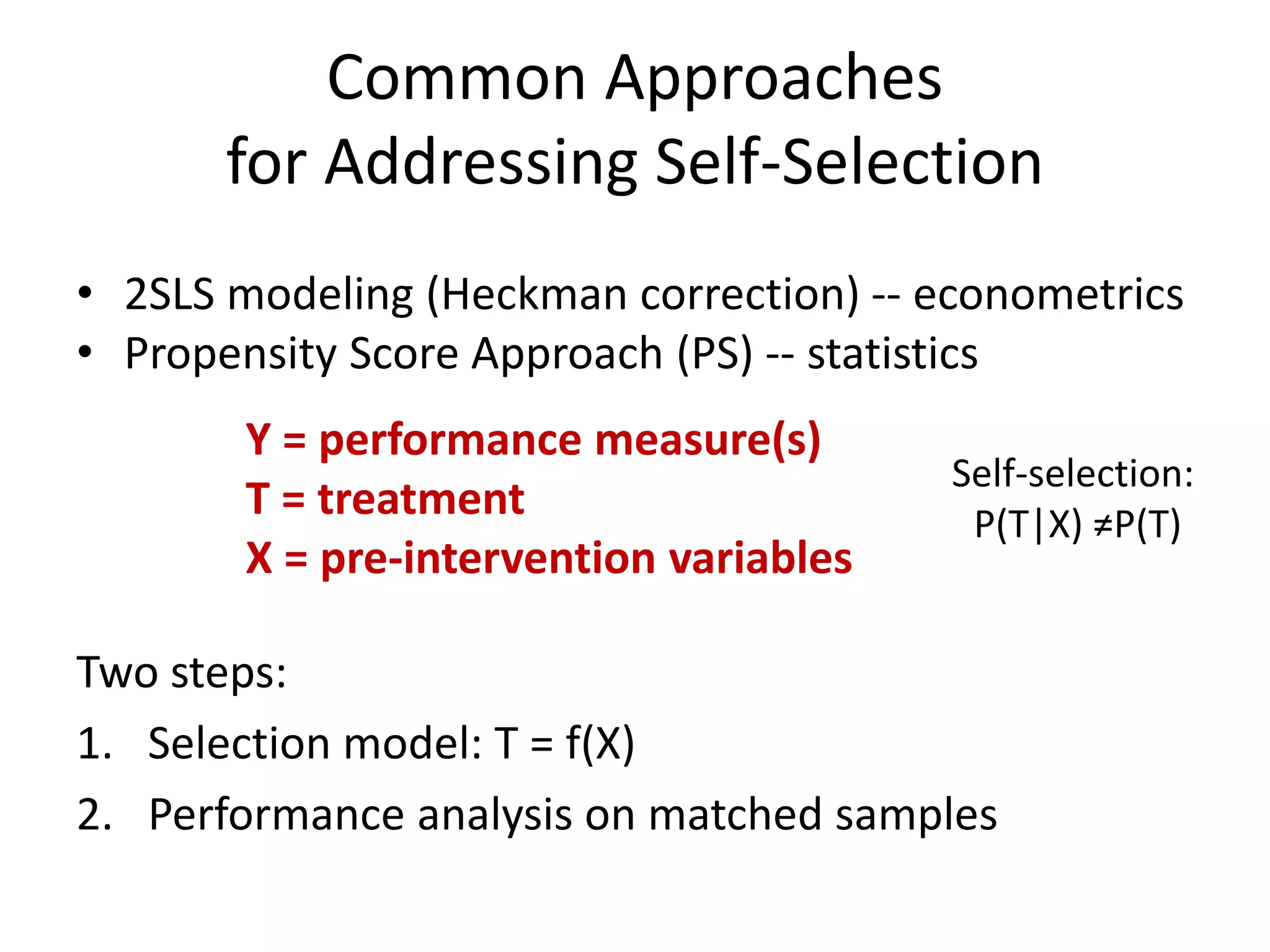

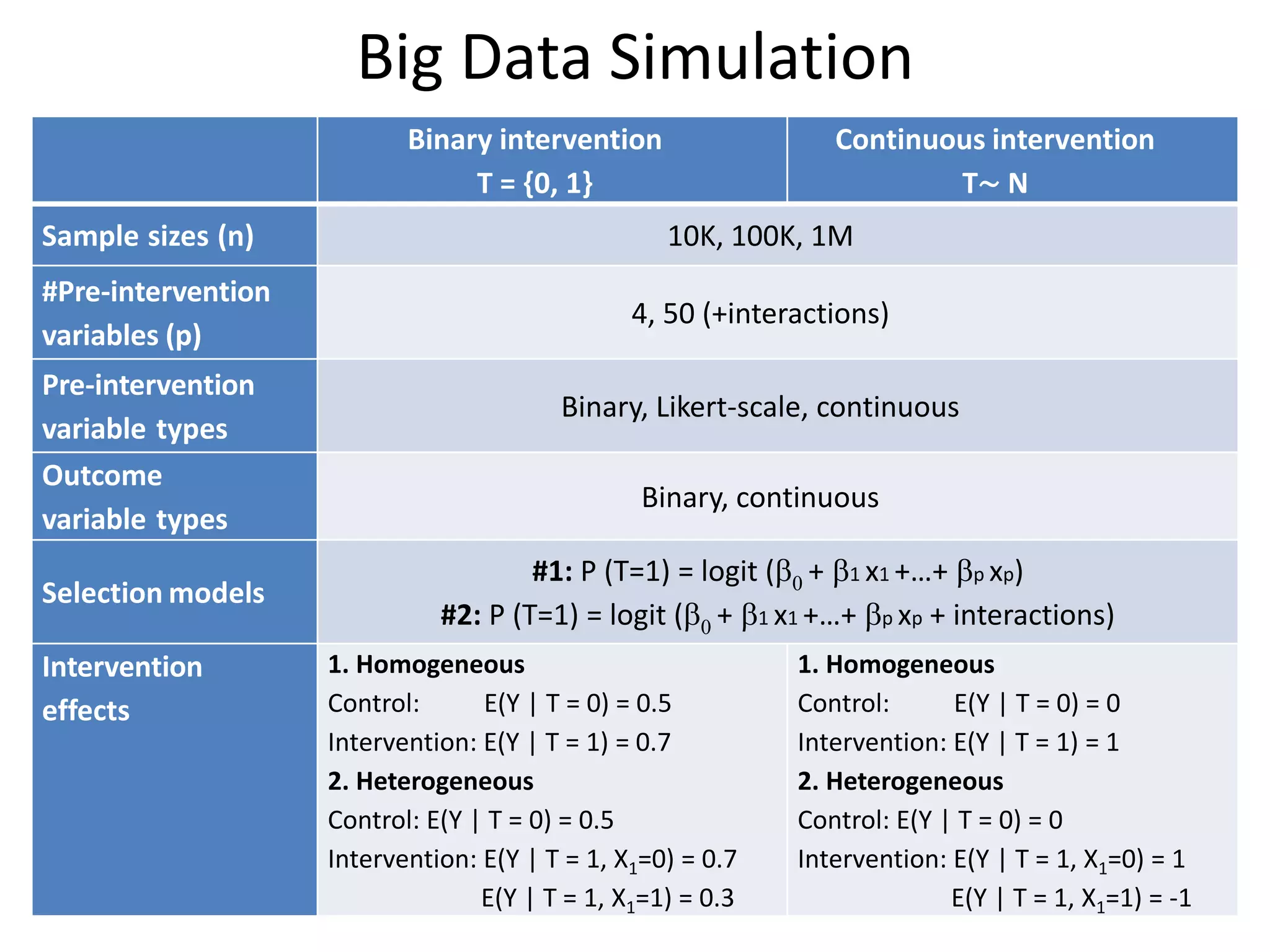

![Tree Approach Limits

1. Assumes selection on observables

2. Need sufficient data

3. Continuous variables can lead to large tree

4. Instability

[possible solution: use variable importance scores (forest)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/treesforcausalresearchwombatmonashnov2019-191129032230/75/Repurposing-Classification-Regression-Trees-for-Causal-Research-with-High-Dimensional-Data-30-2048.jpg)

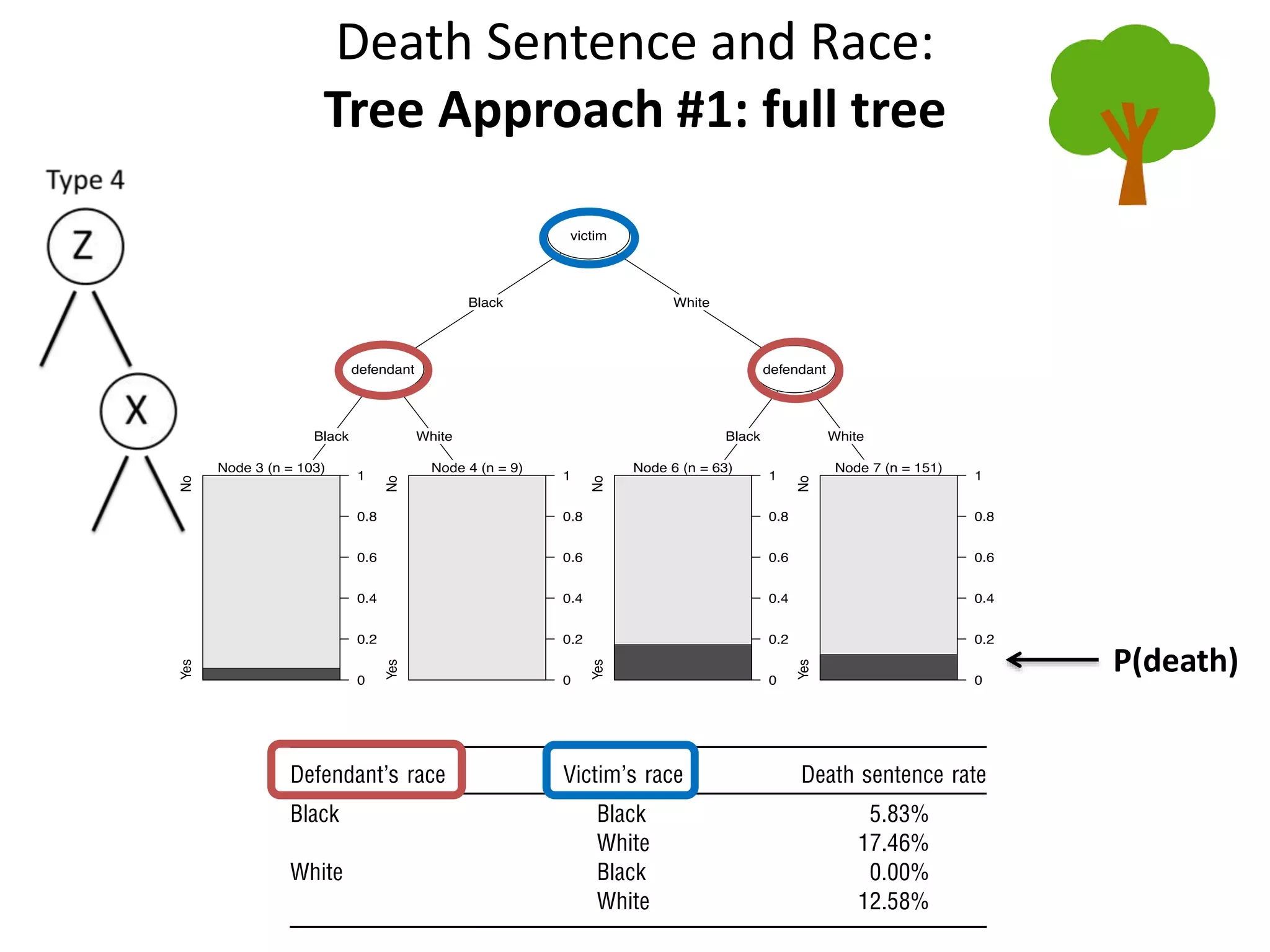

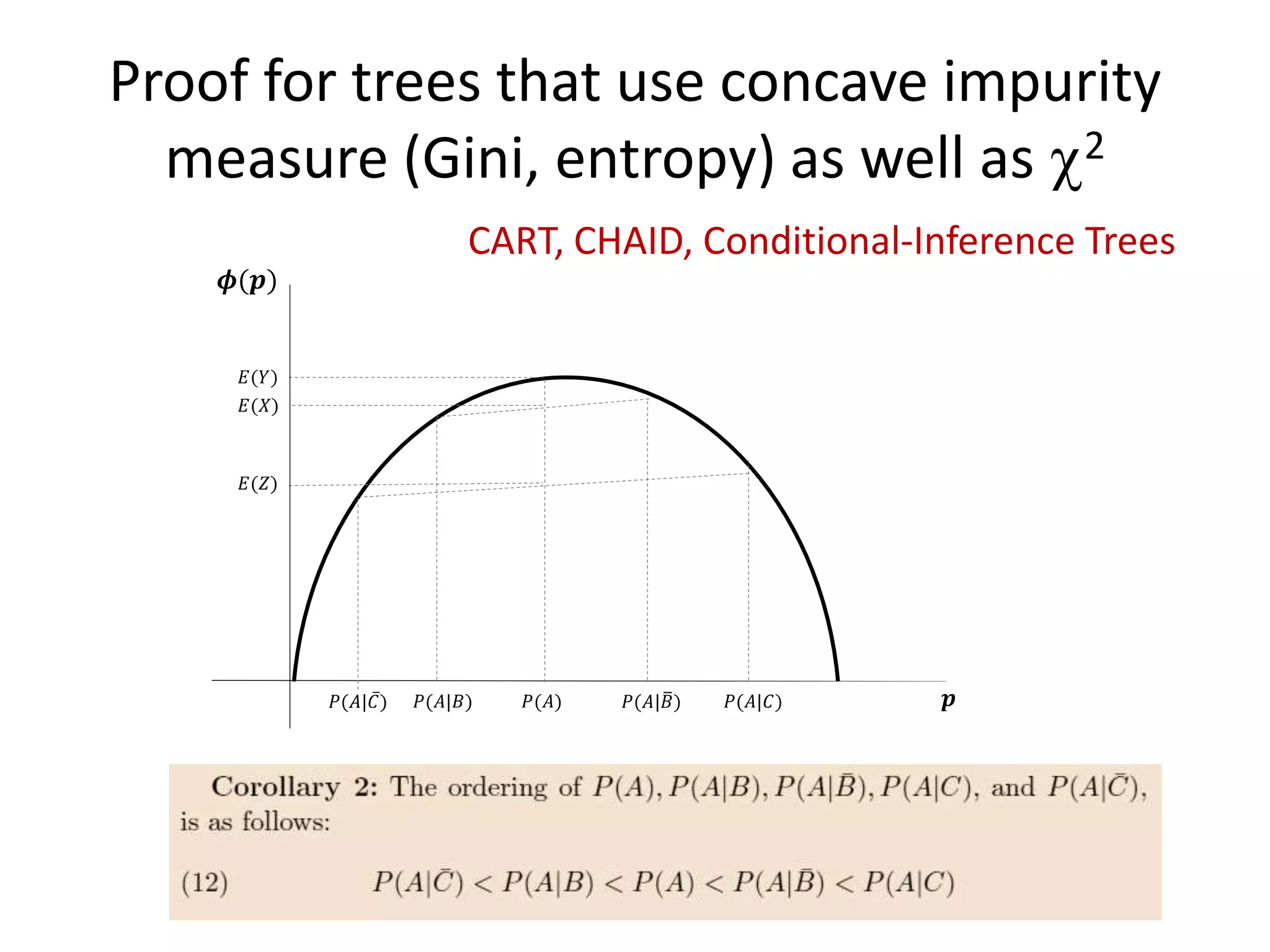

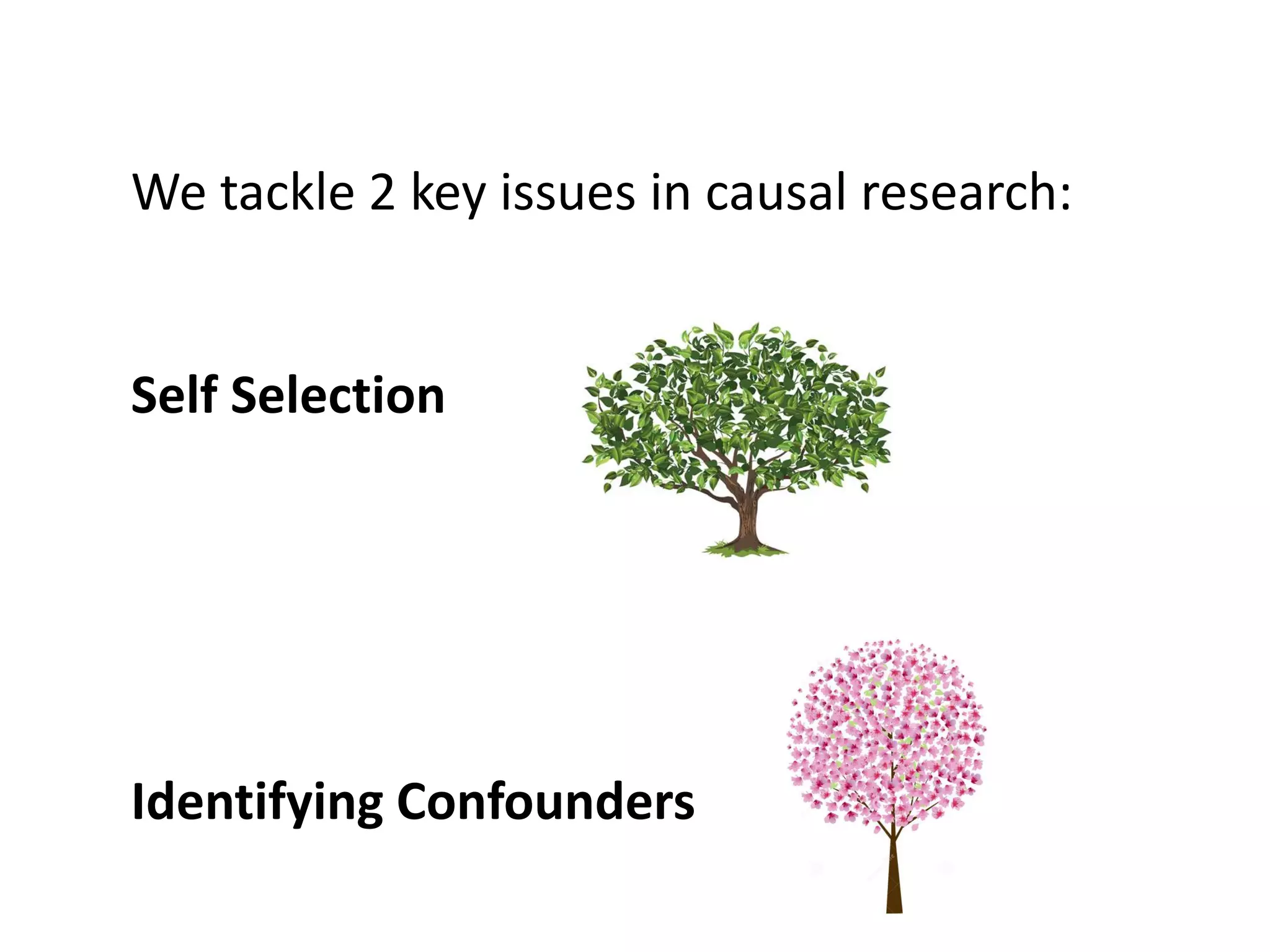

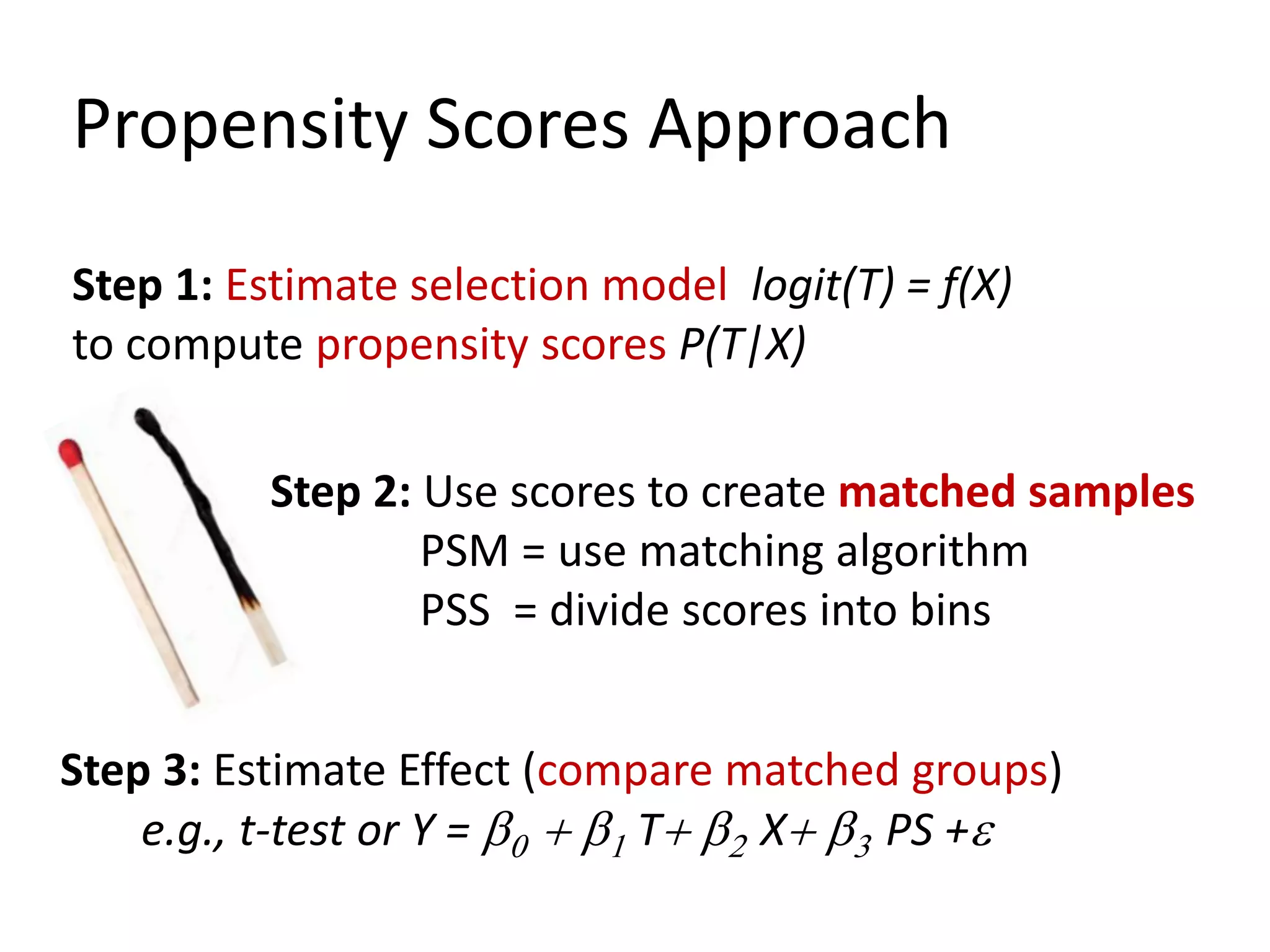

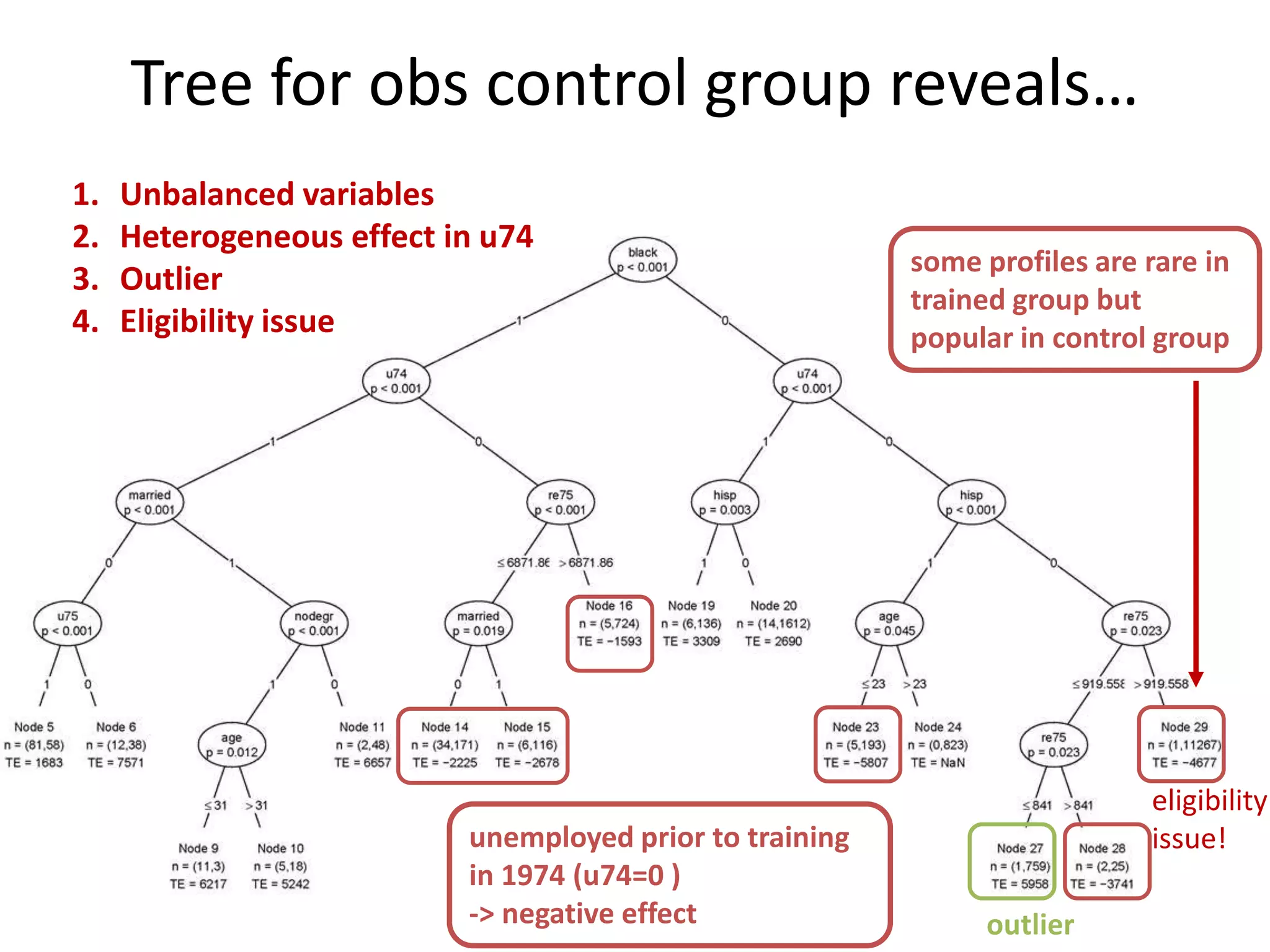

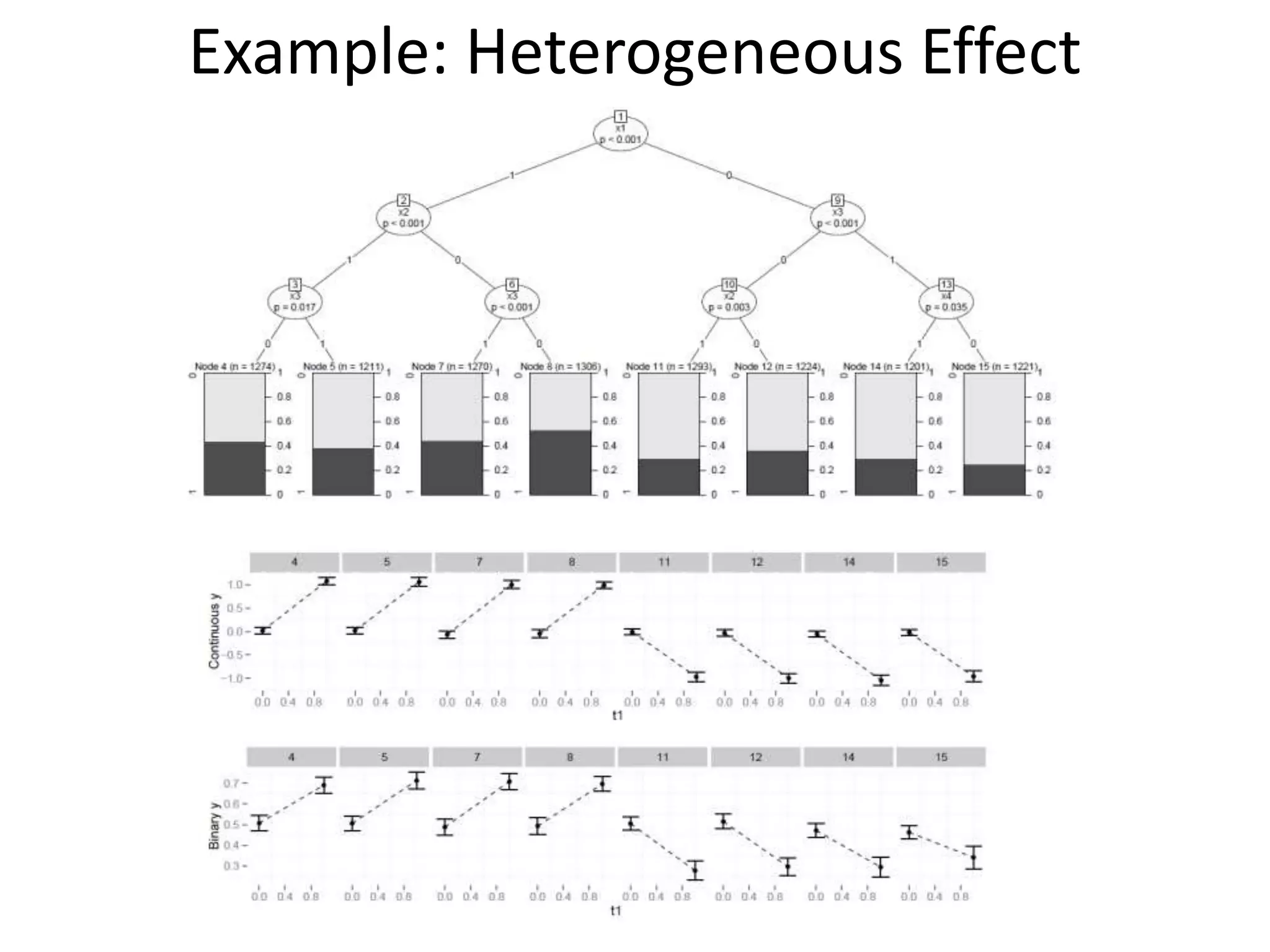

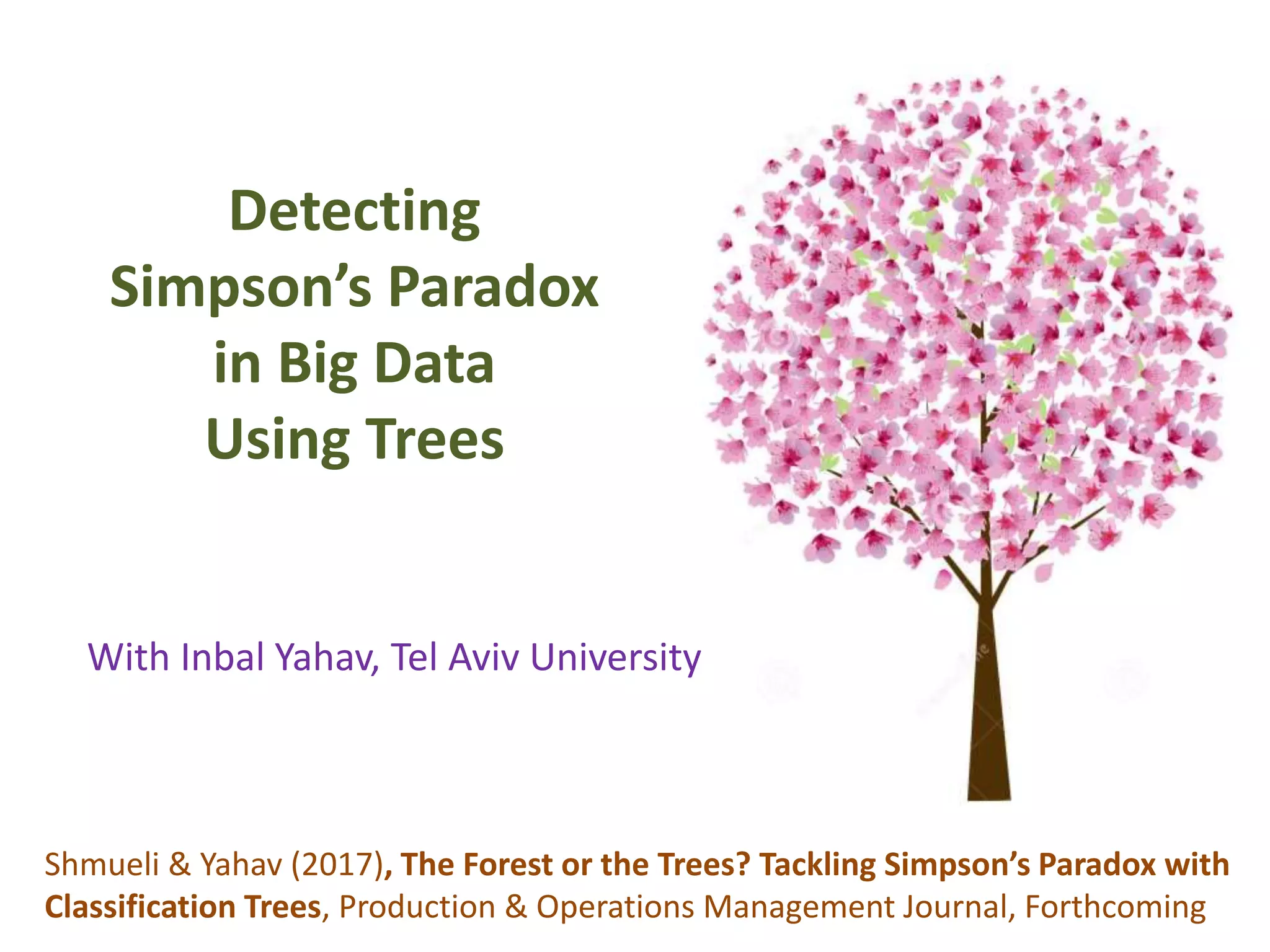

![Goal: Does a dataset exhibit SP?

C = confounder

E = effectA = cause

P (E|C ) – P( E|C’ ) P (E|A ) – P(E|A’ )

“If Cornfield’s minimum effect size is not reached,

[you] can assume no causality” Schield, 1999

Cornfield et al’s Criterion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/treesforcausalresearchwombatmonashnov2019-191129032230/75/Repurposing-Classification-Regression-Trees-for-Causal-Research-with-High-Dimensional-Data-34-2048.jpg)