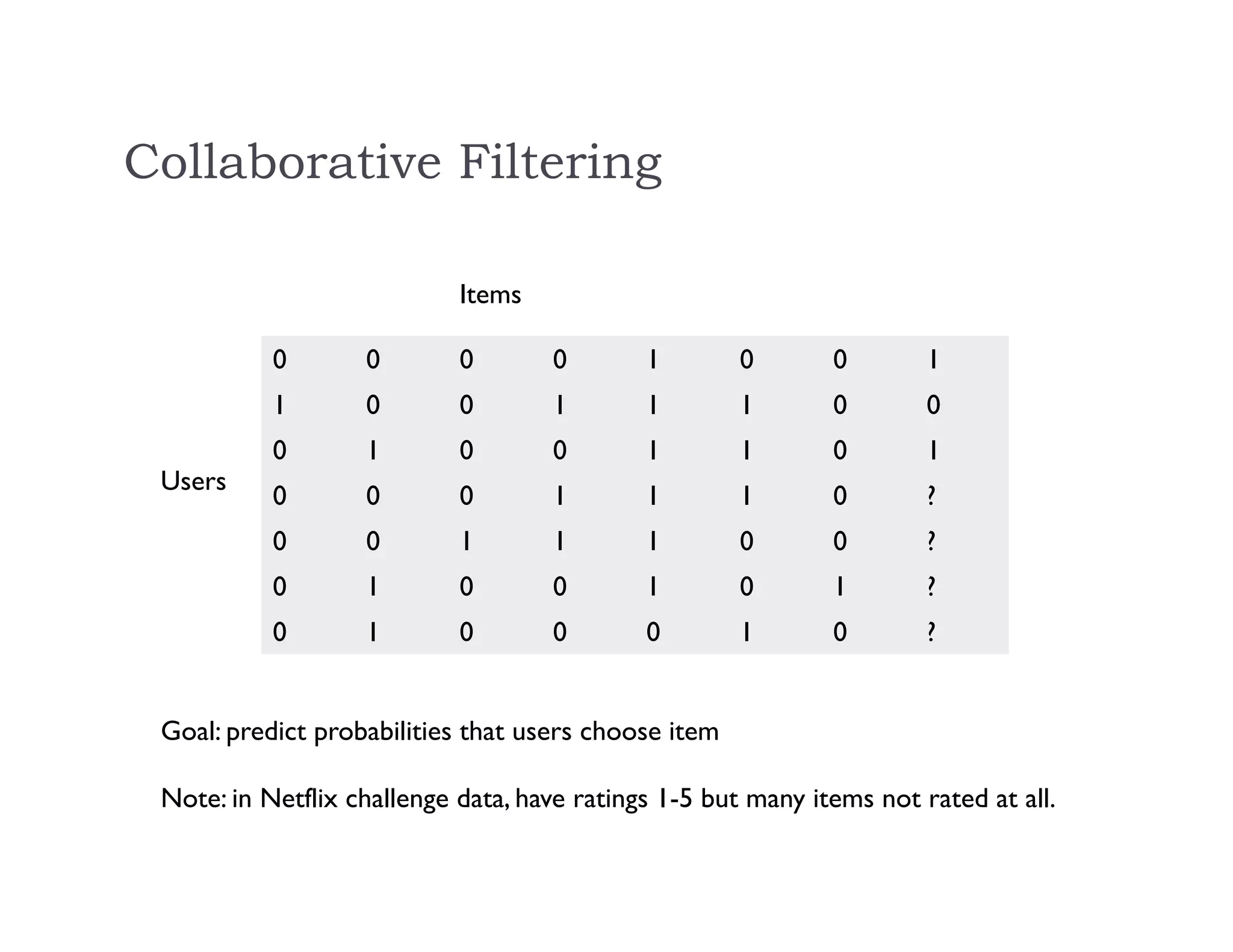

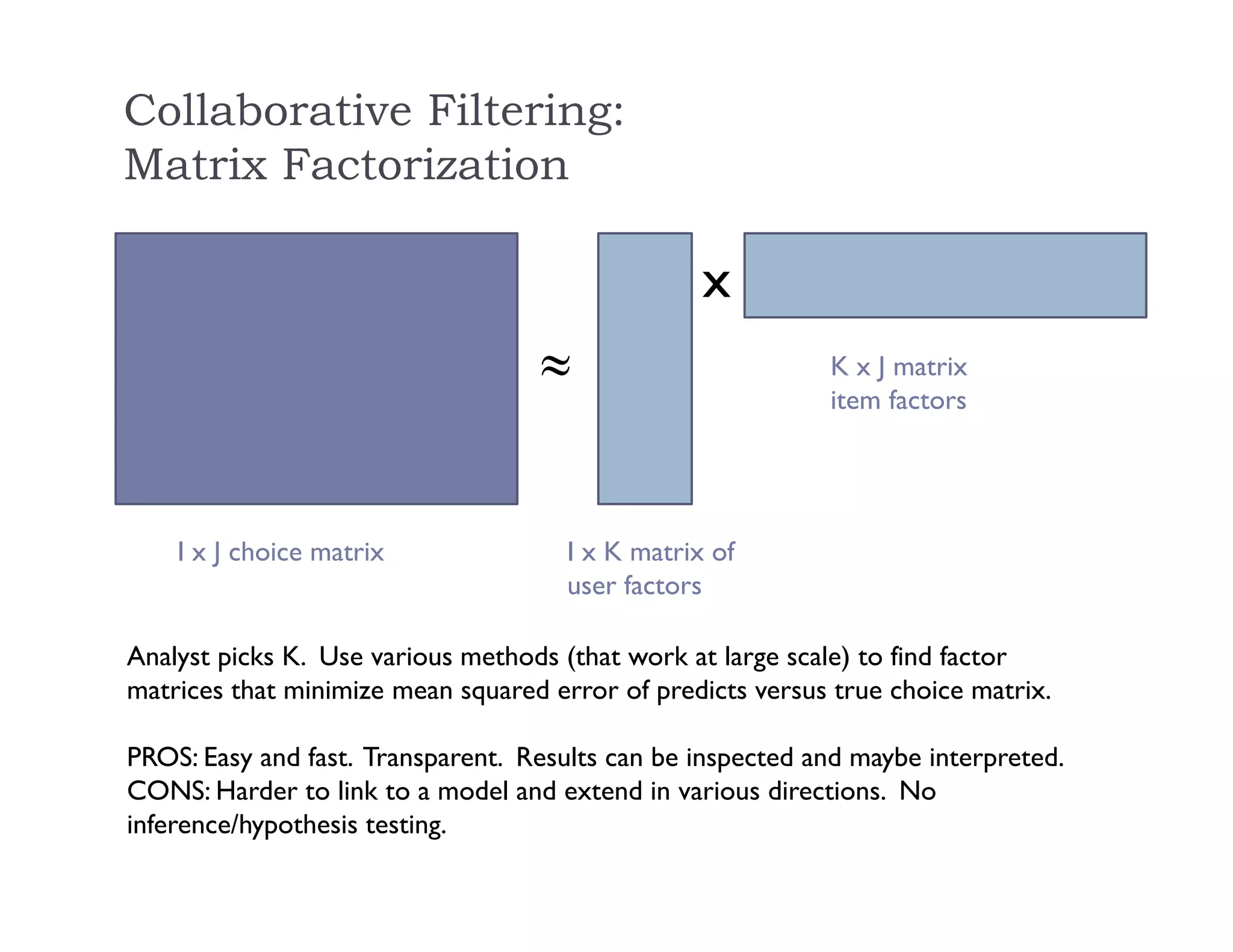

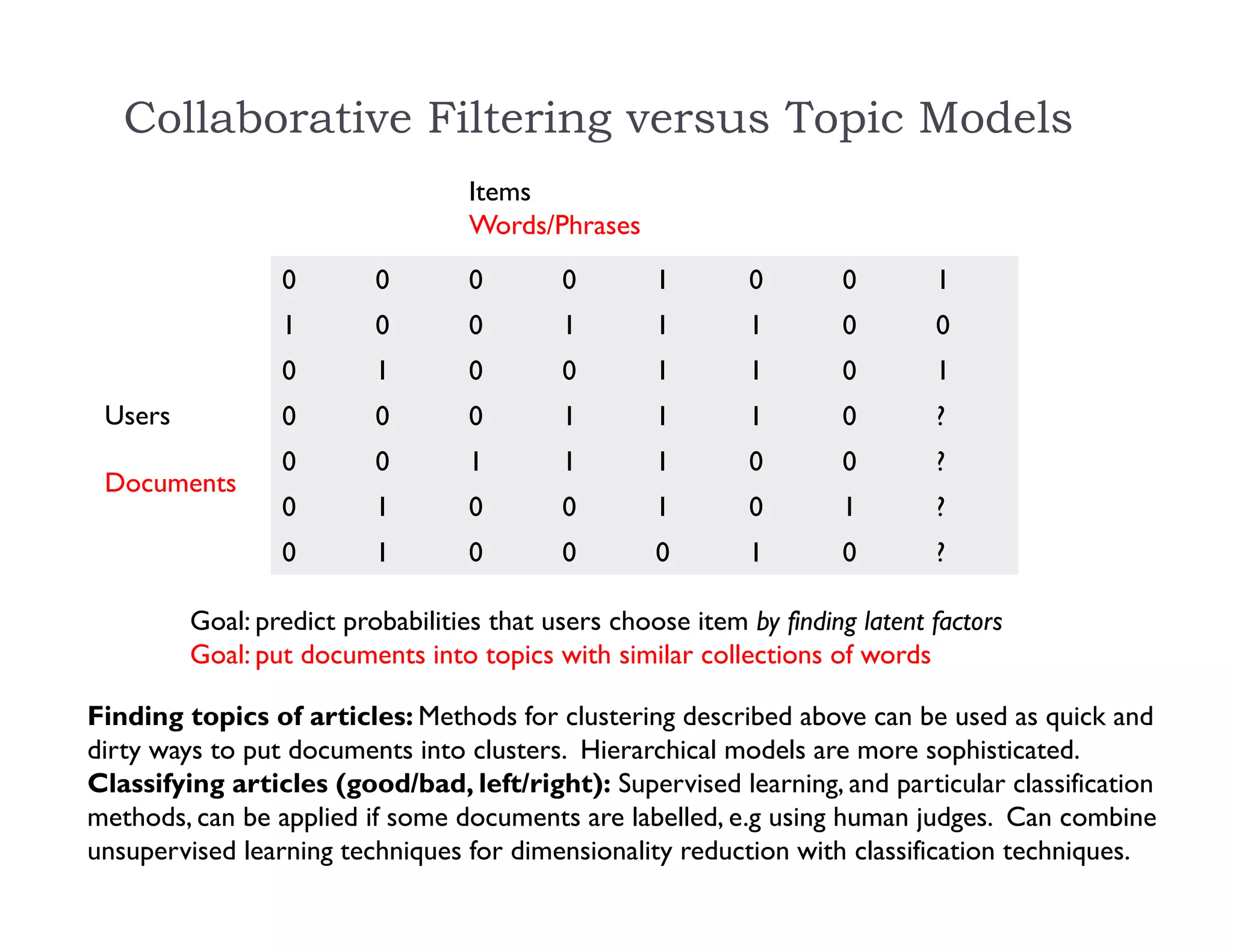

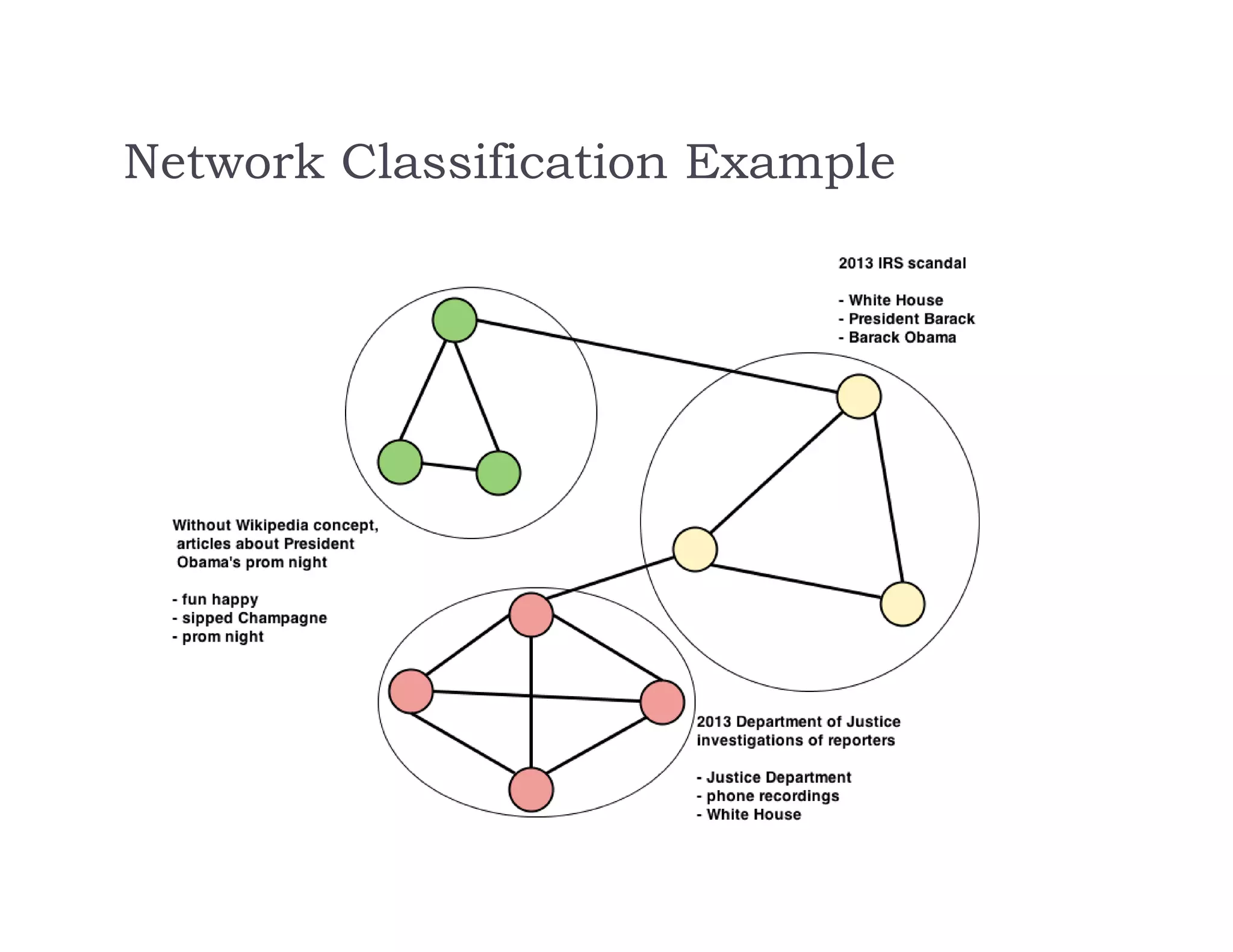

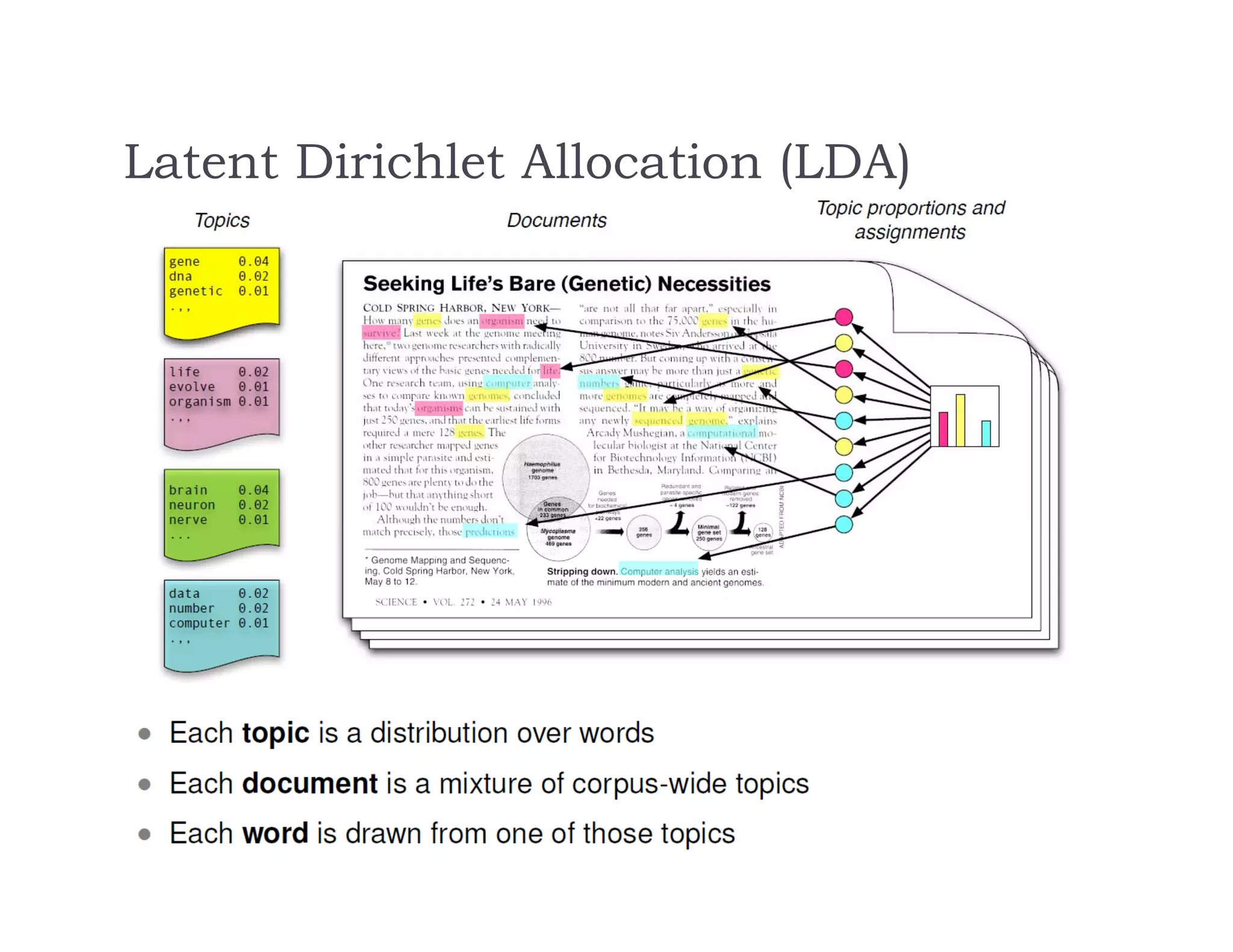

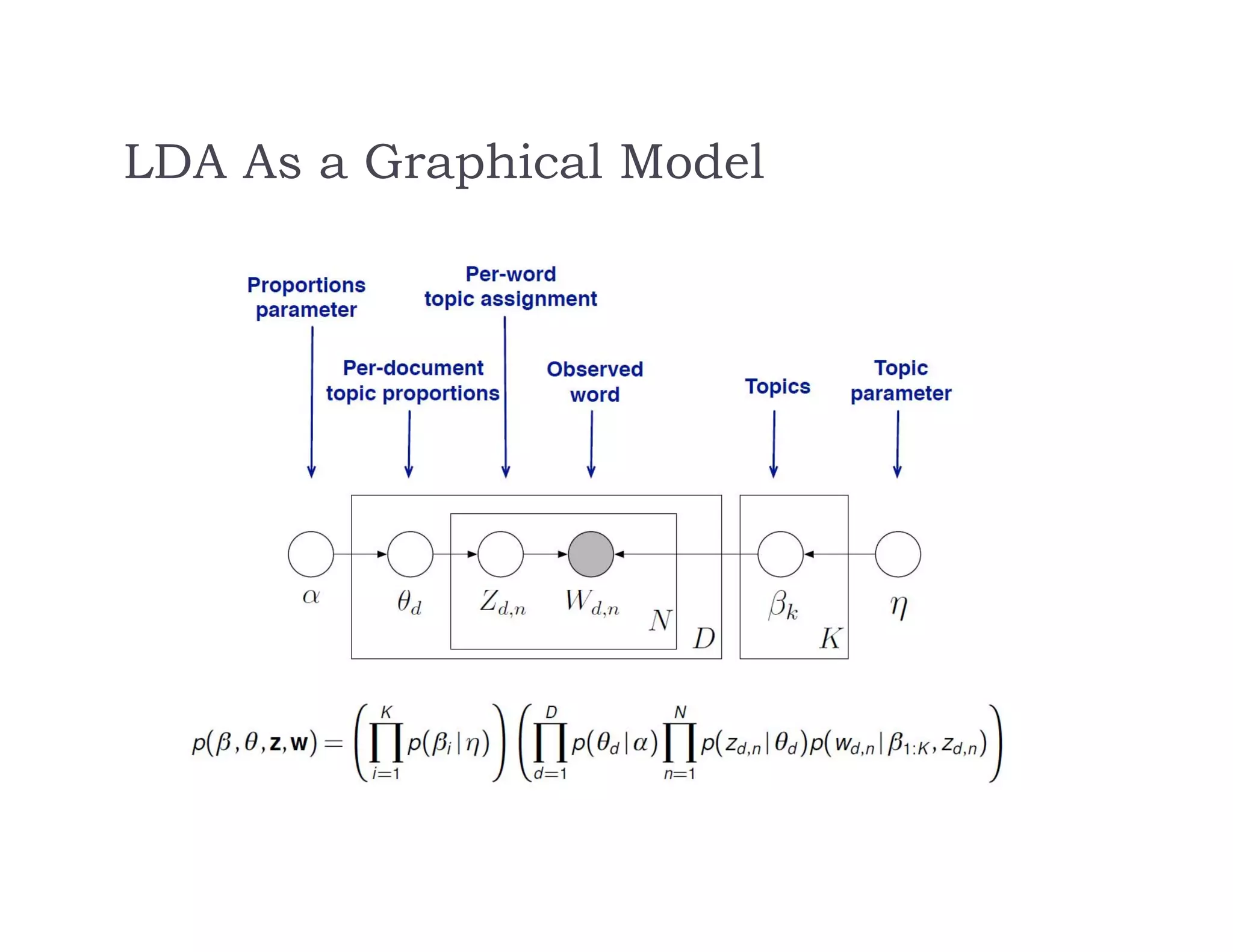

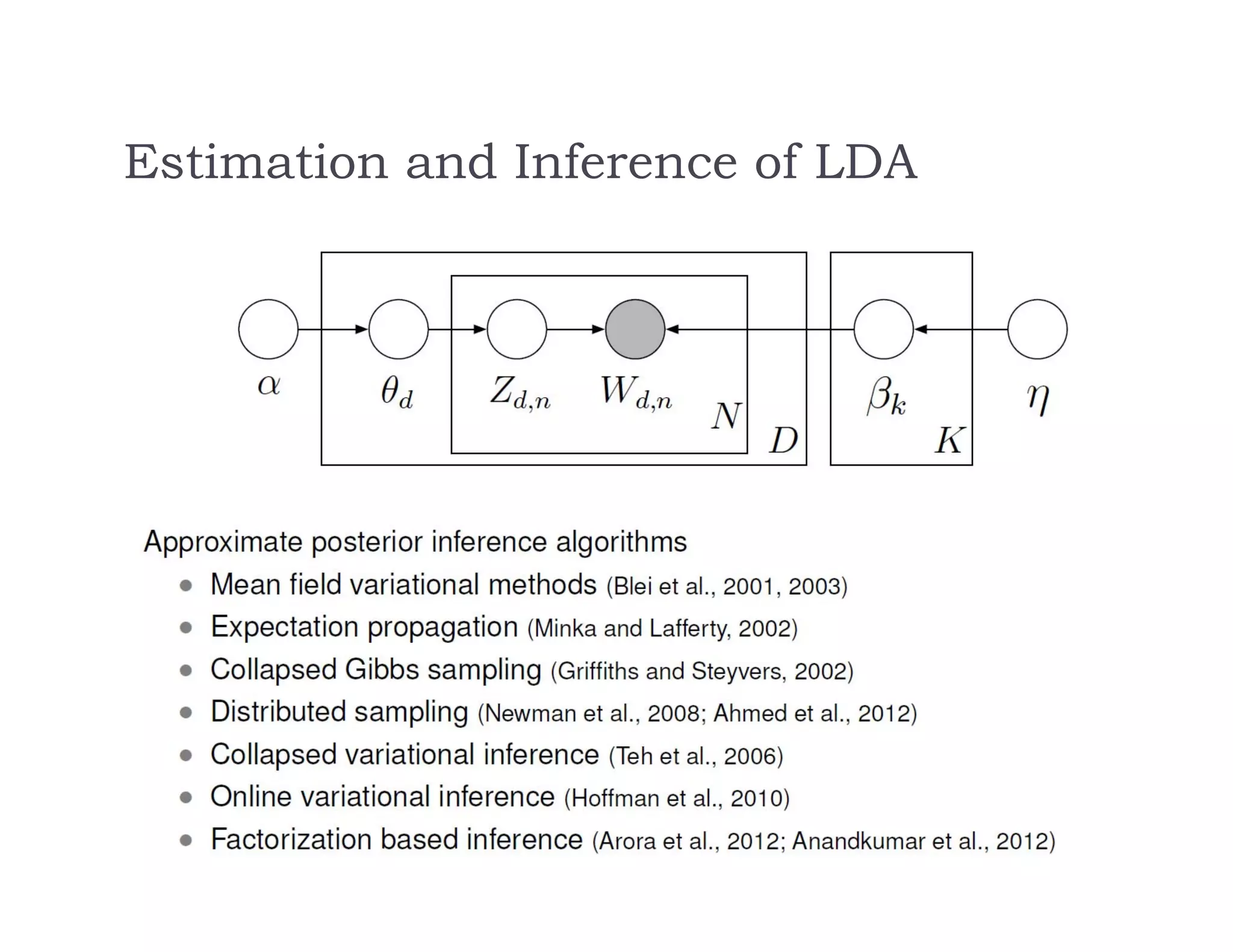

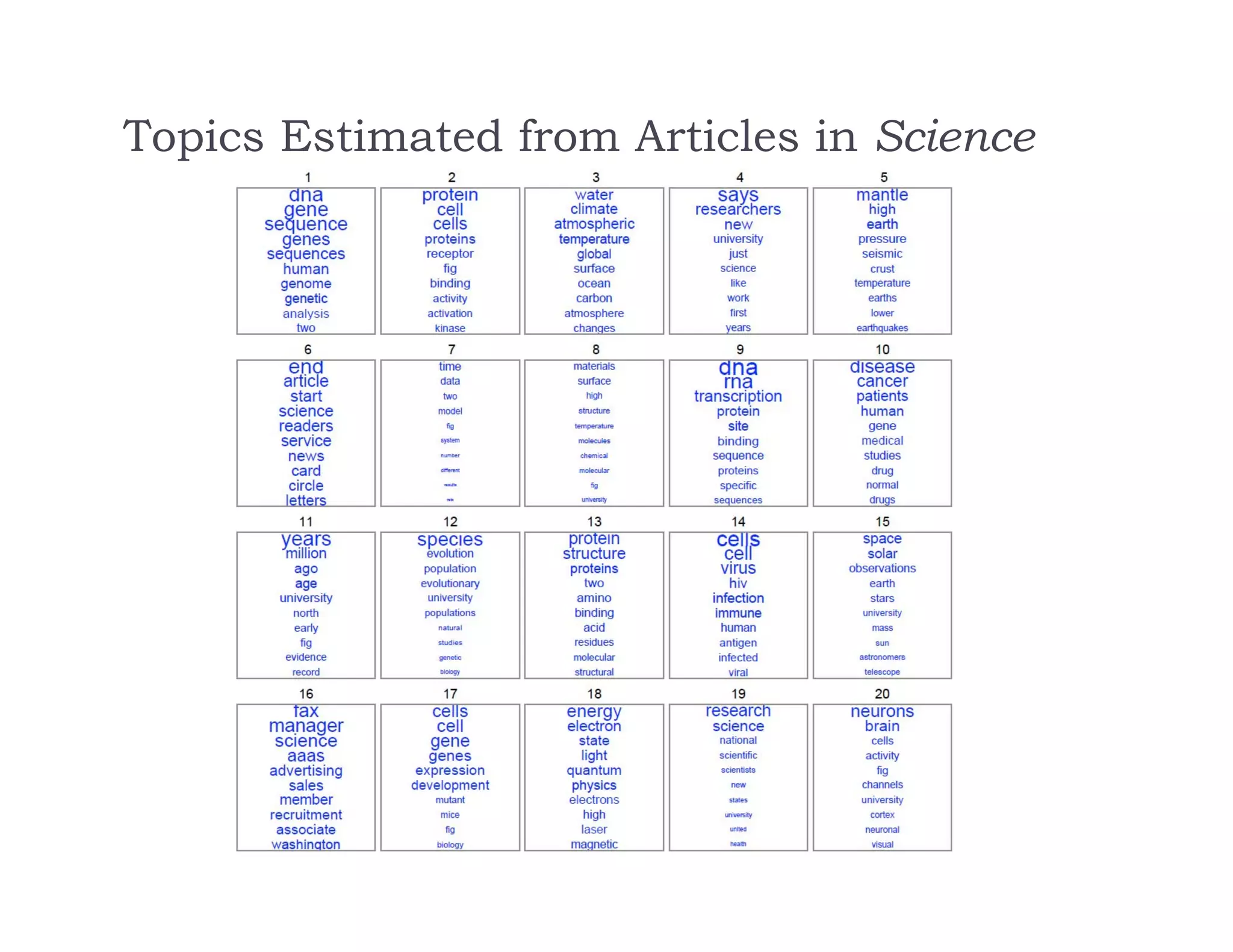

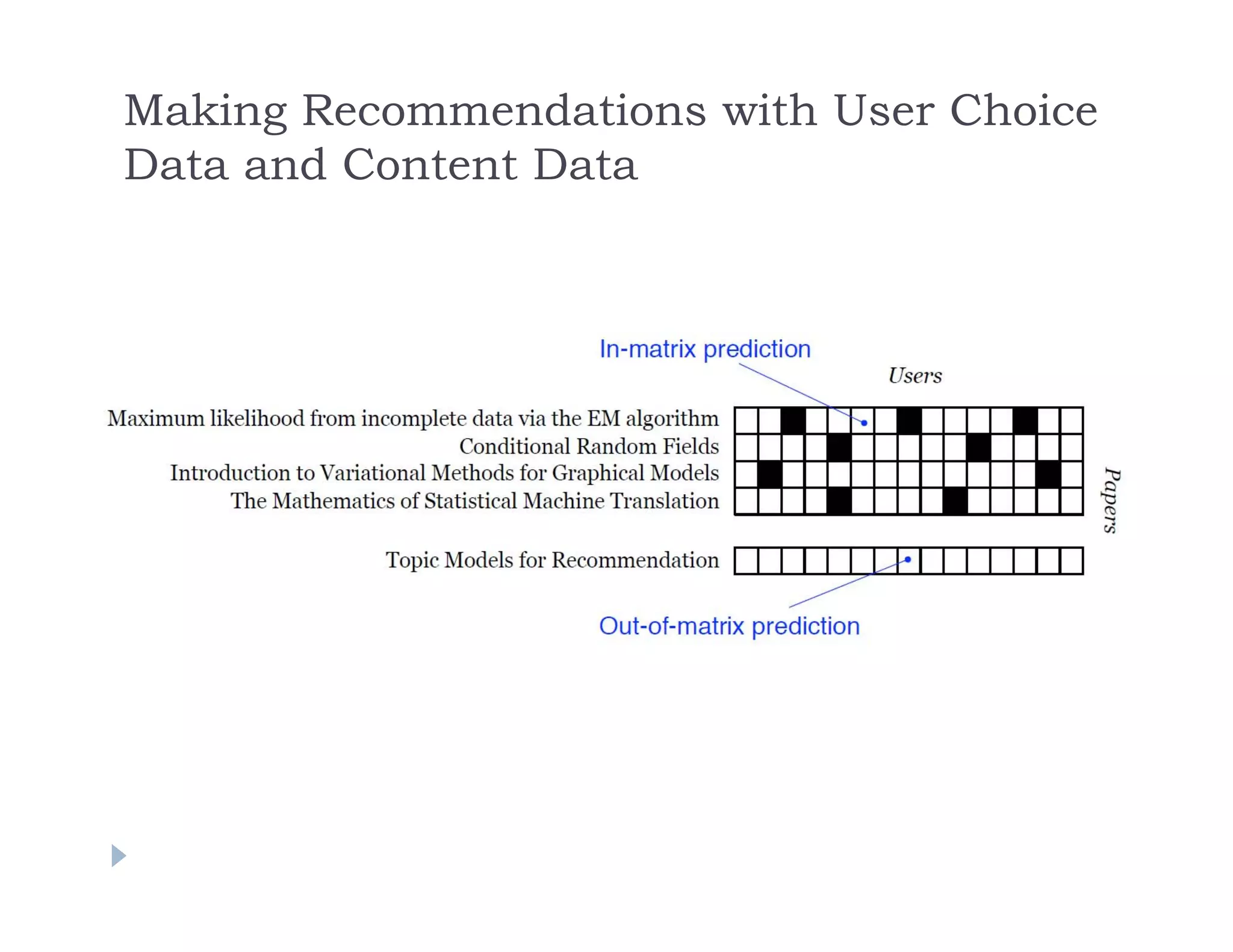

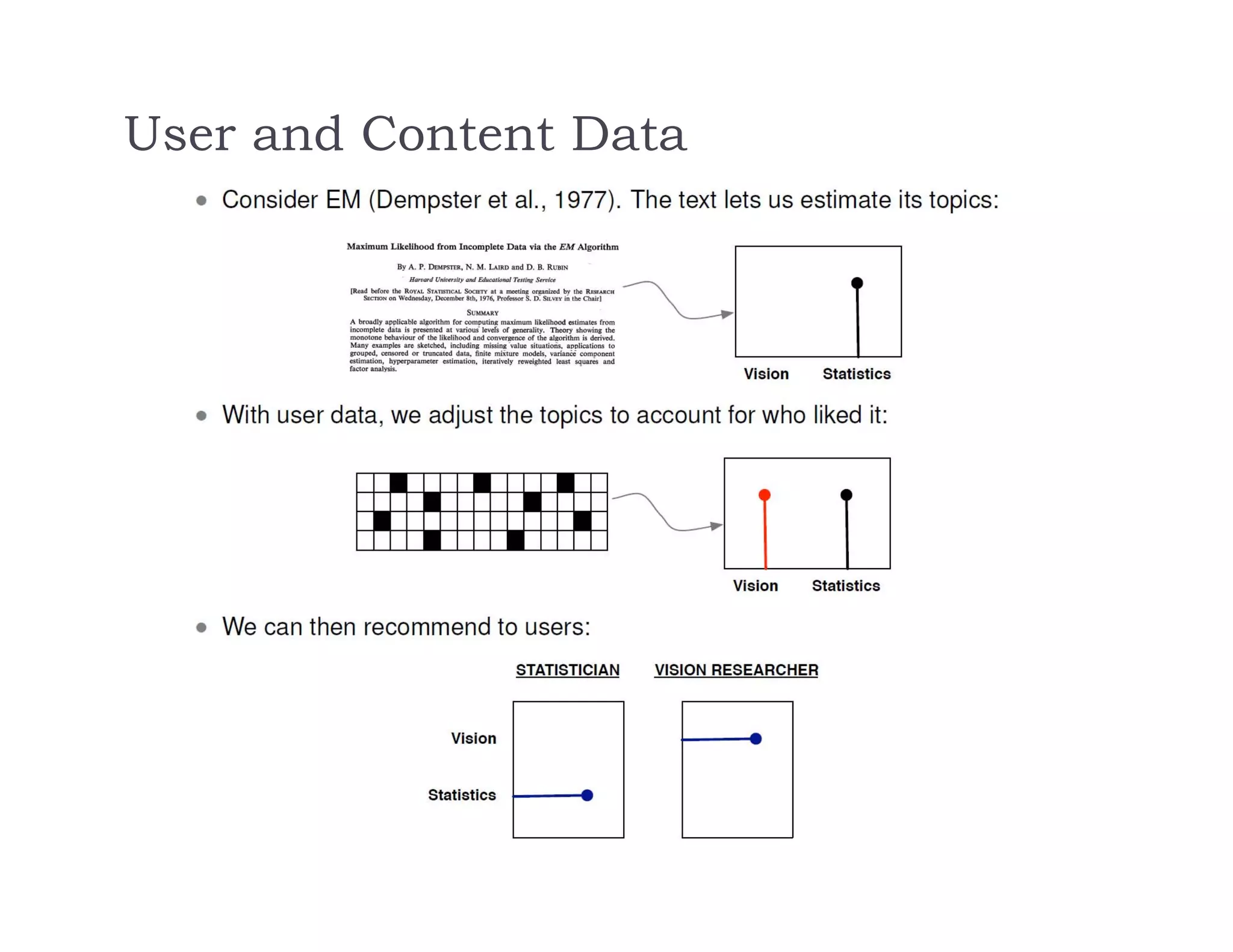

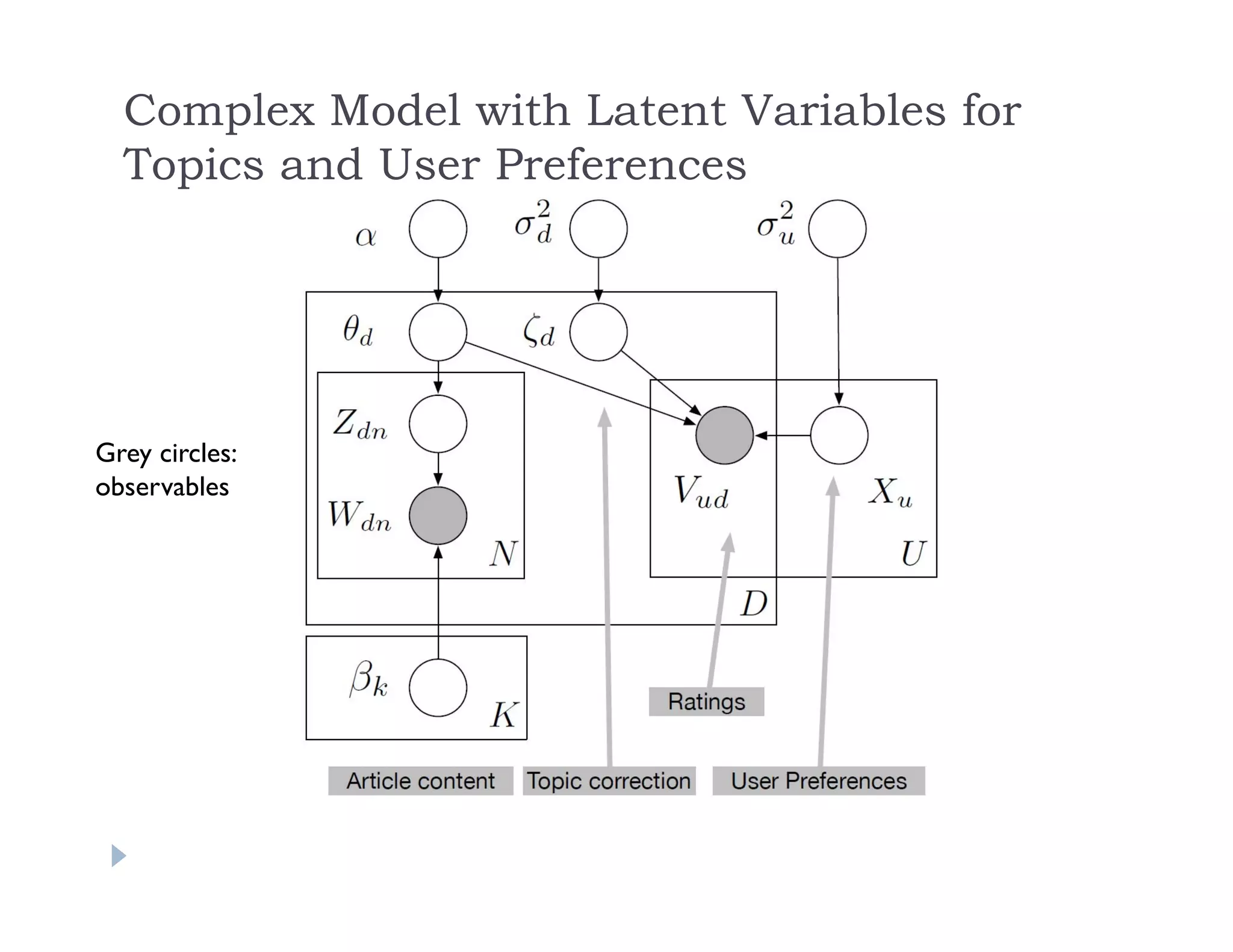

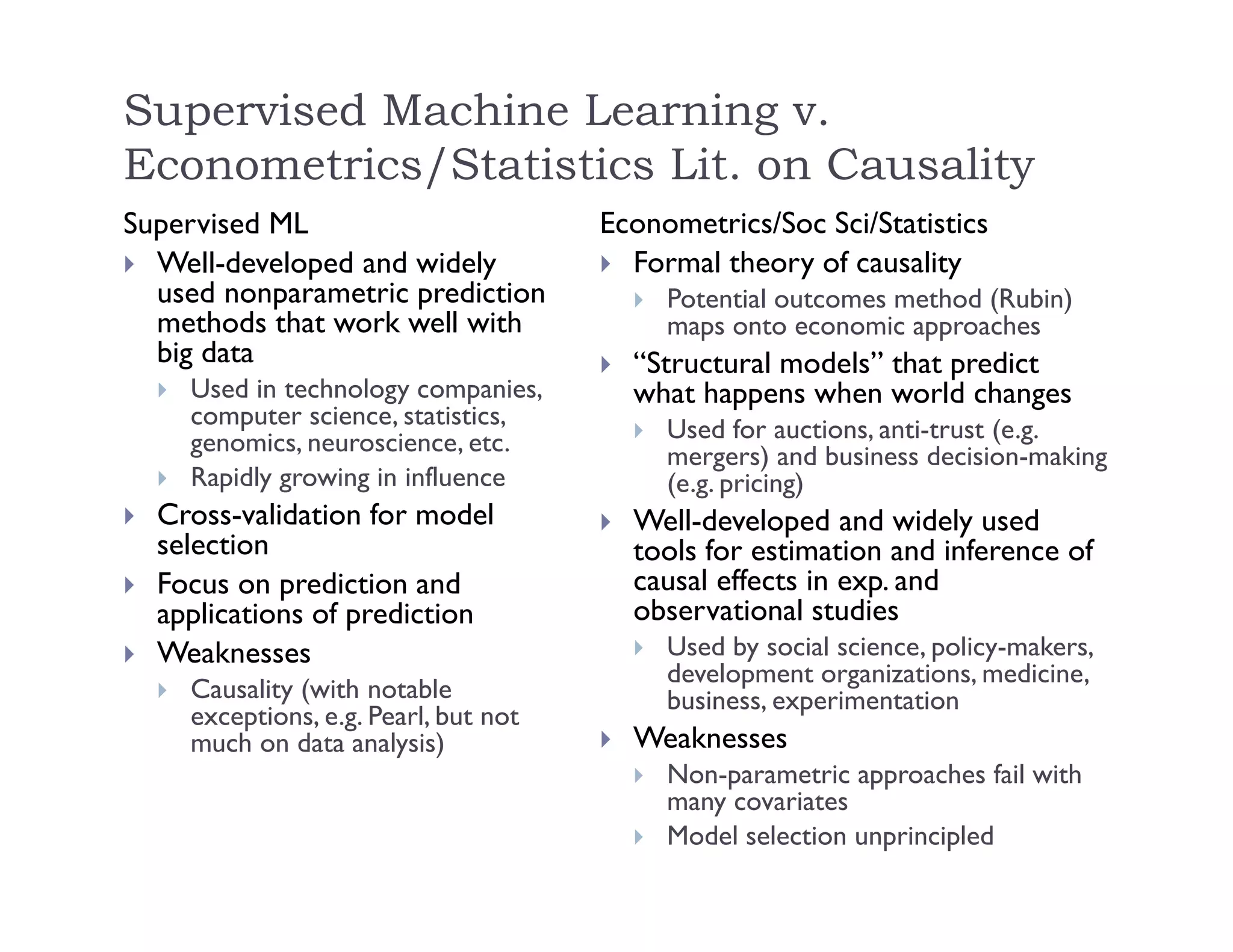

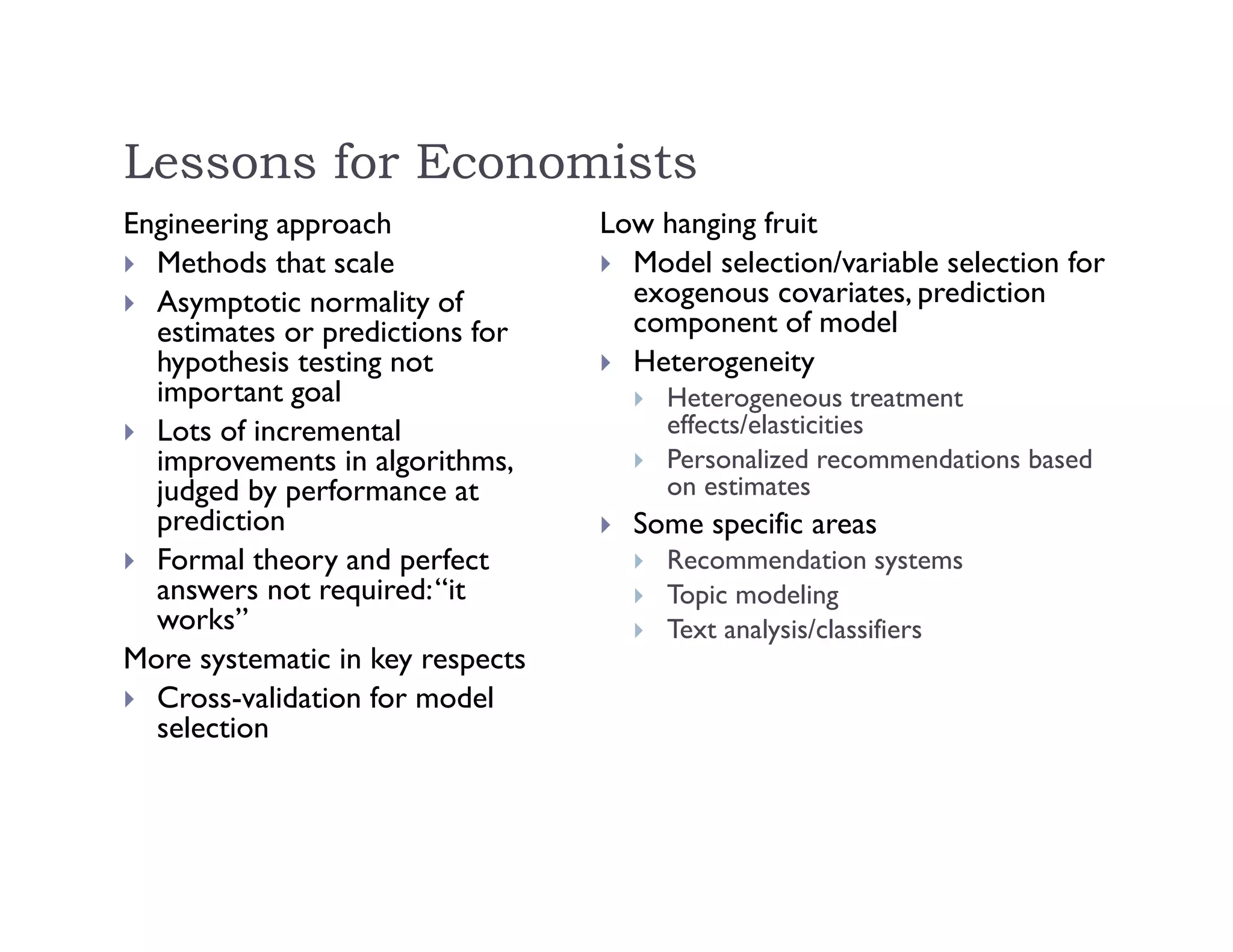

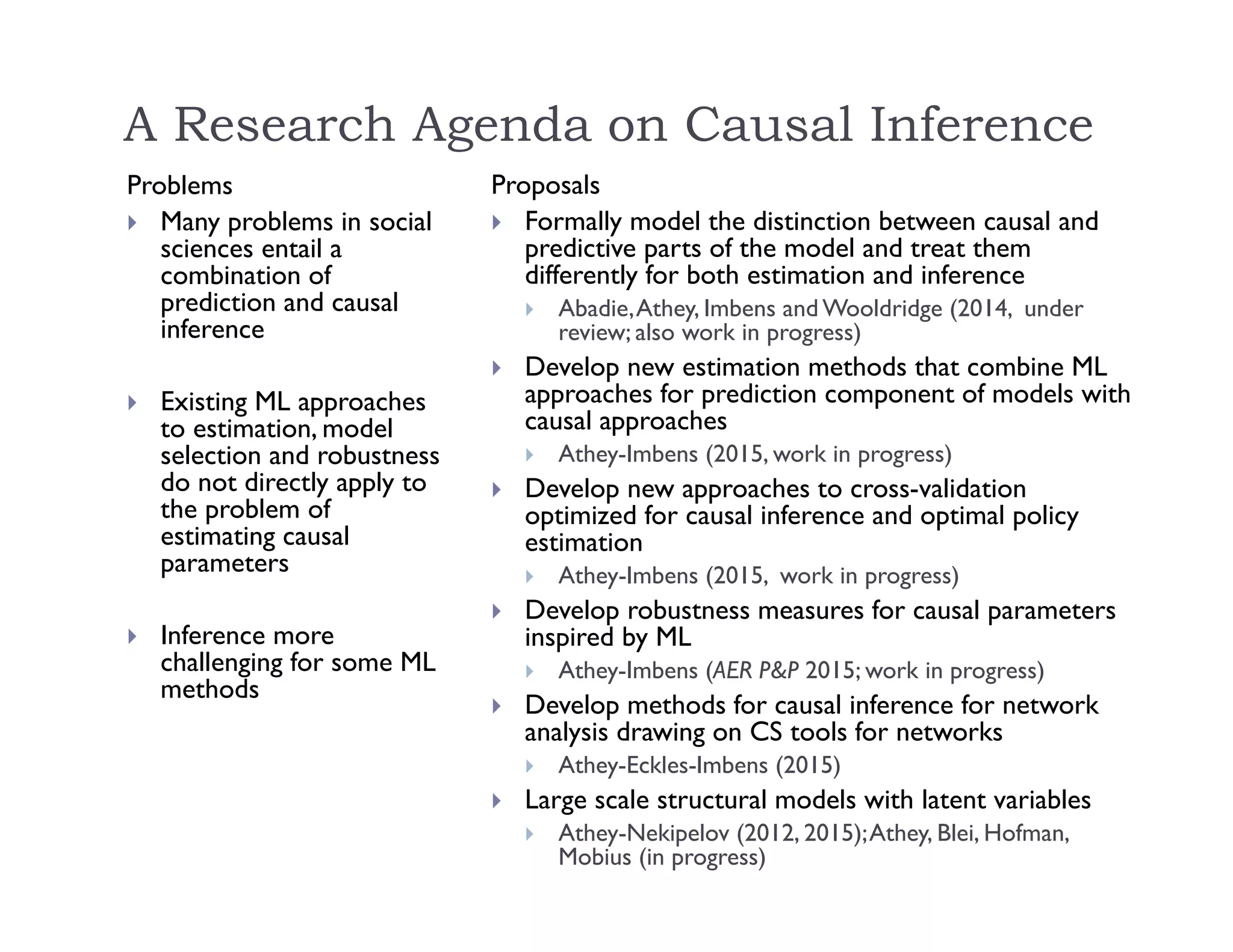

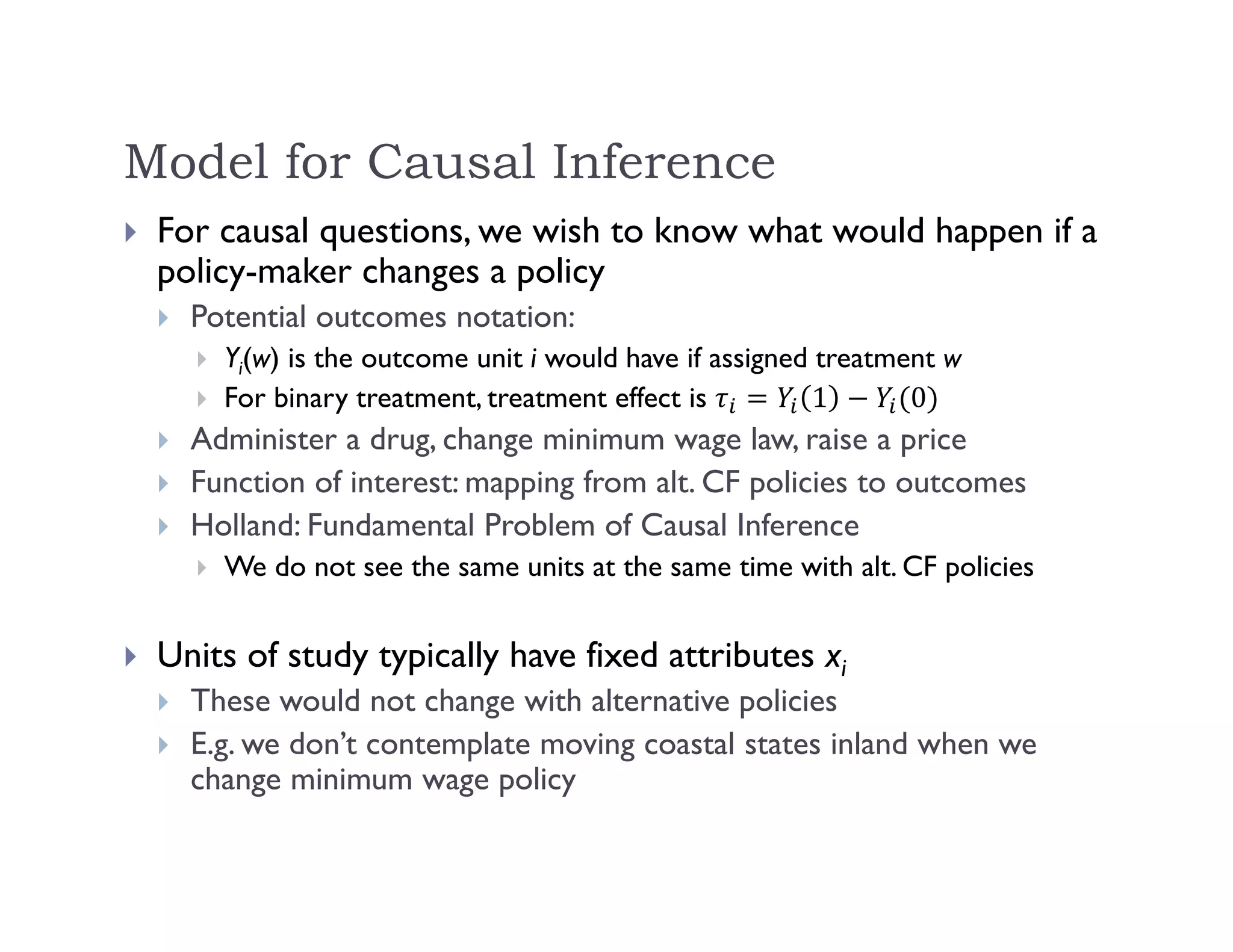

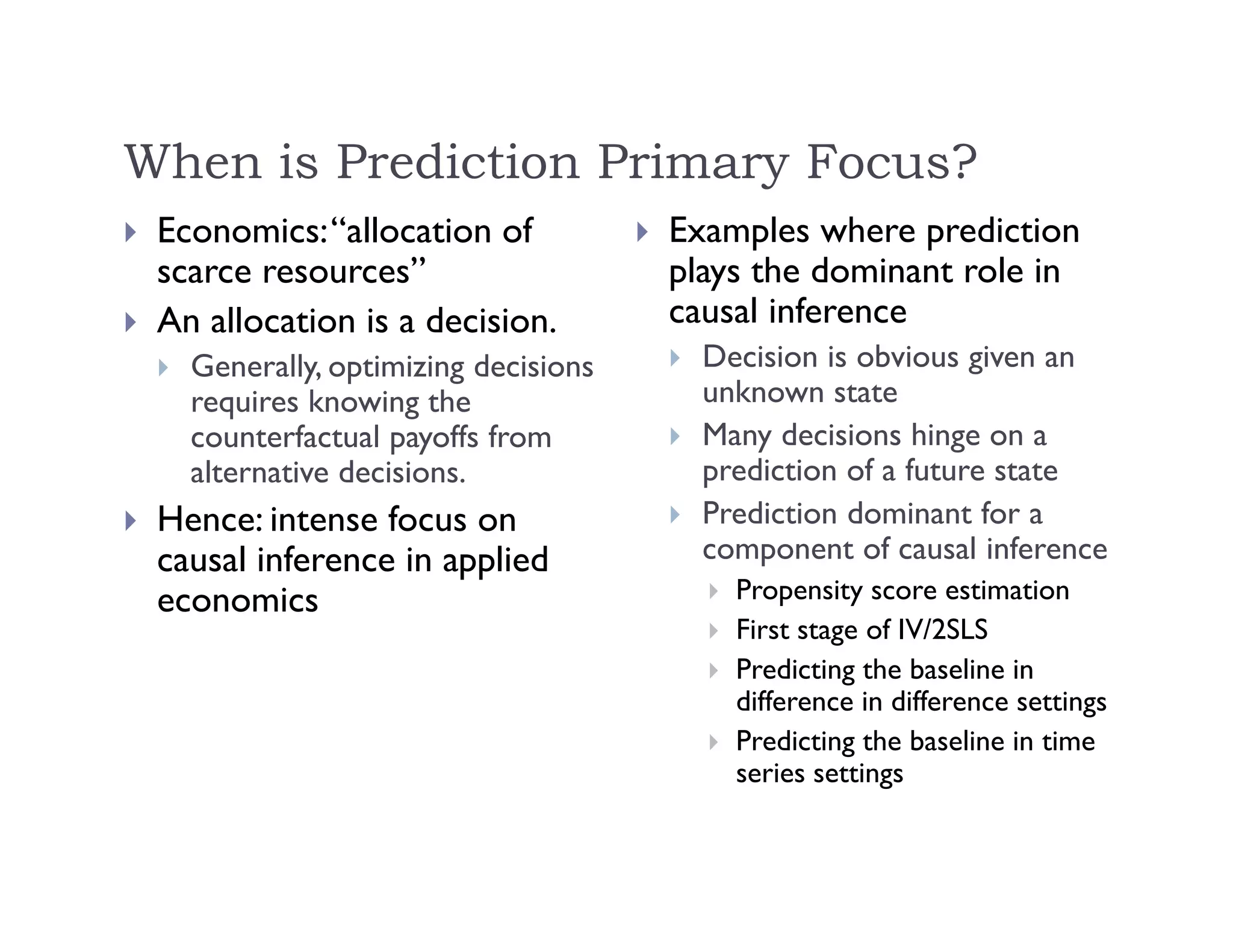

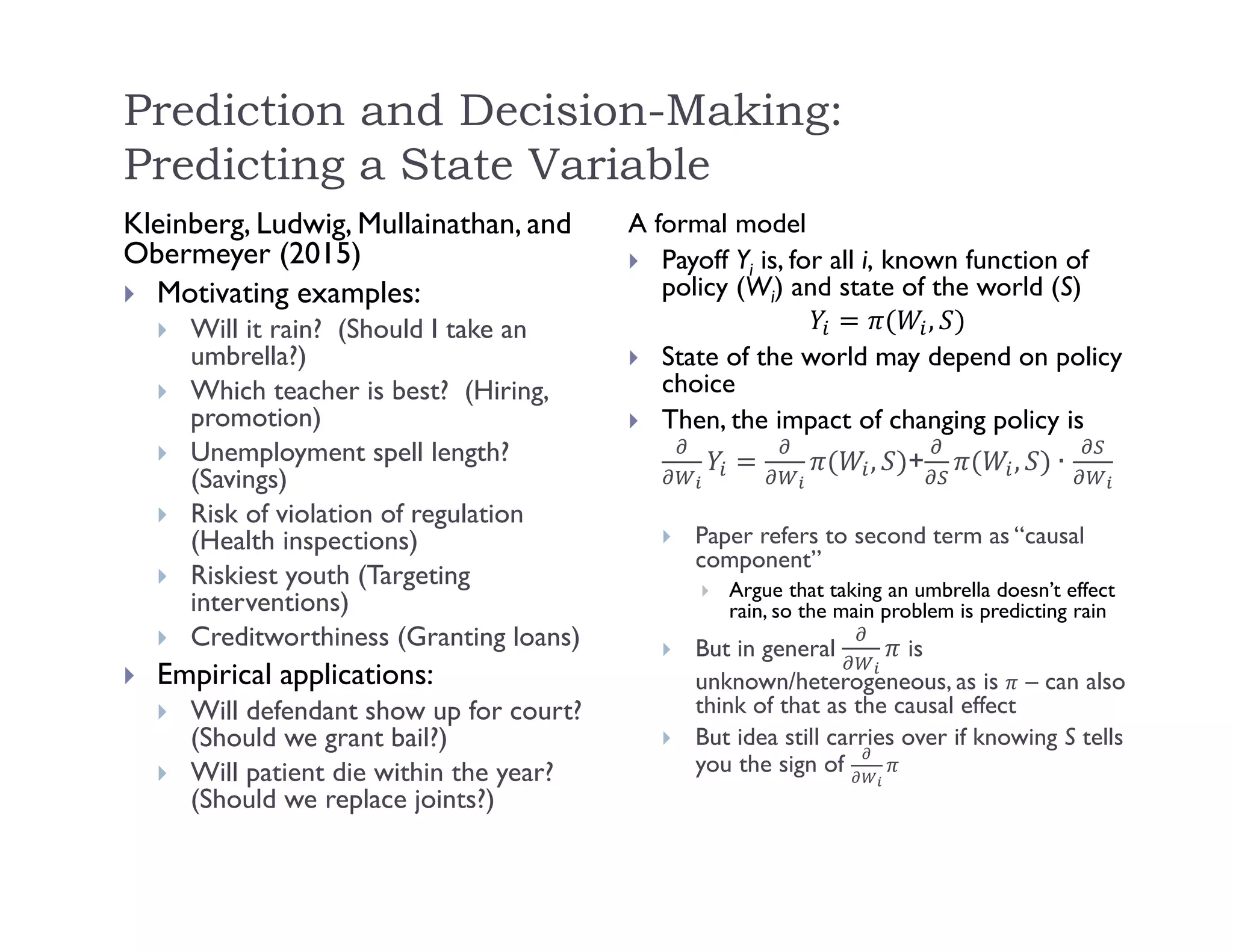

This document discusses recommendation systems and topic modeling for documents using machine learning techniques. It begins by introducing recommendation systems and different types of recommendation literature, including item similarity, collaborative filtering, and hierarchical models. It then discusses bringing in user choice data and different collaborative filtering approaches like k-nearest neighbor prediction and matrix factorization. The document also covers topic modeling, including latent Dirichlet allocation, and how topic models can be combined with user choice models. It concludes by discussing challenges in causal inference when using machine learning.