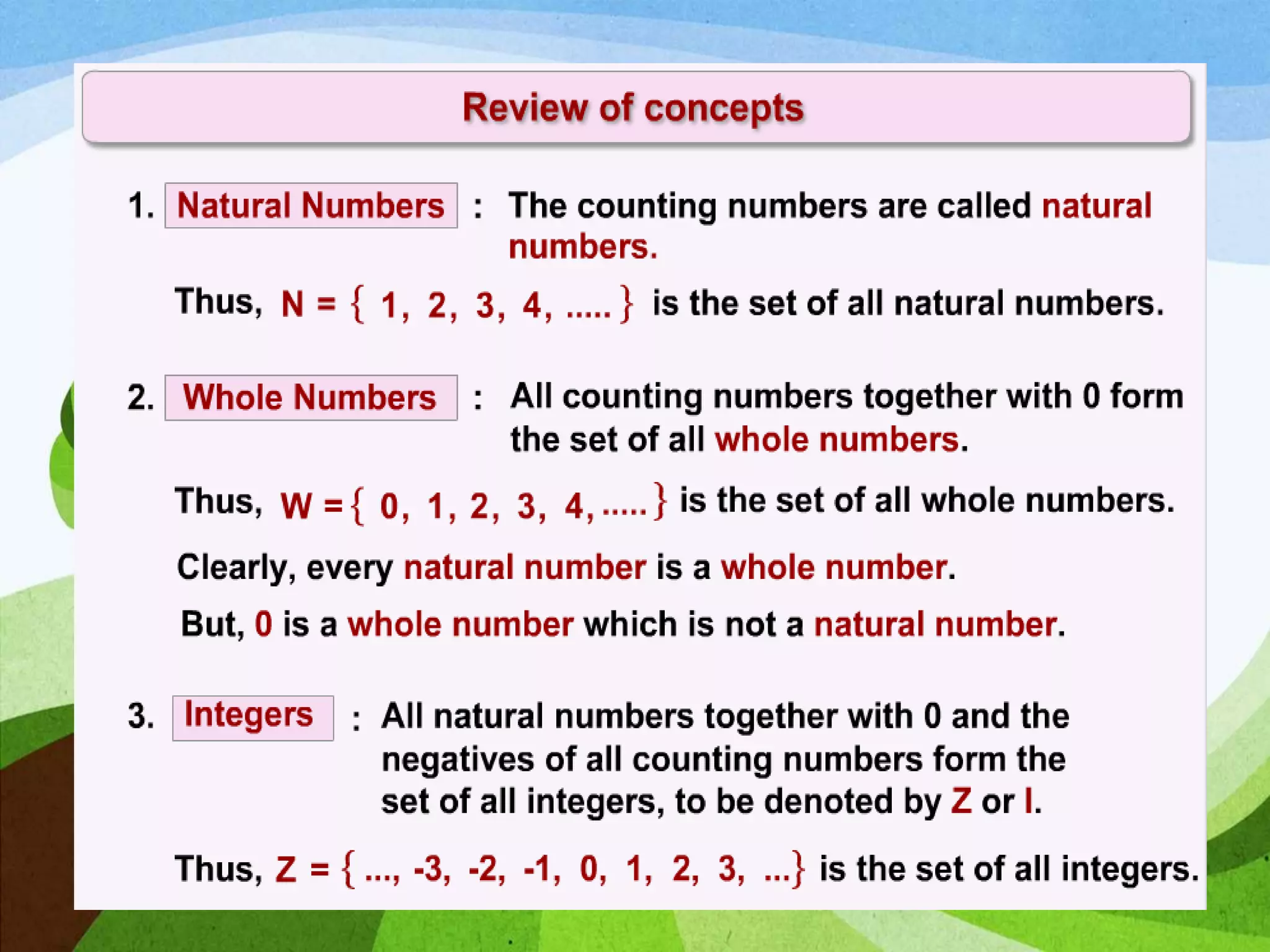

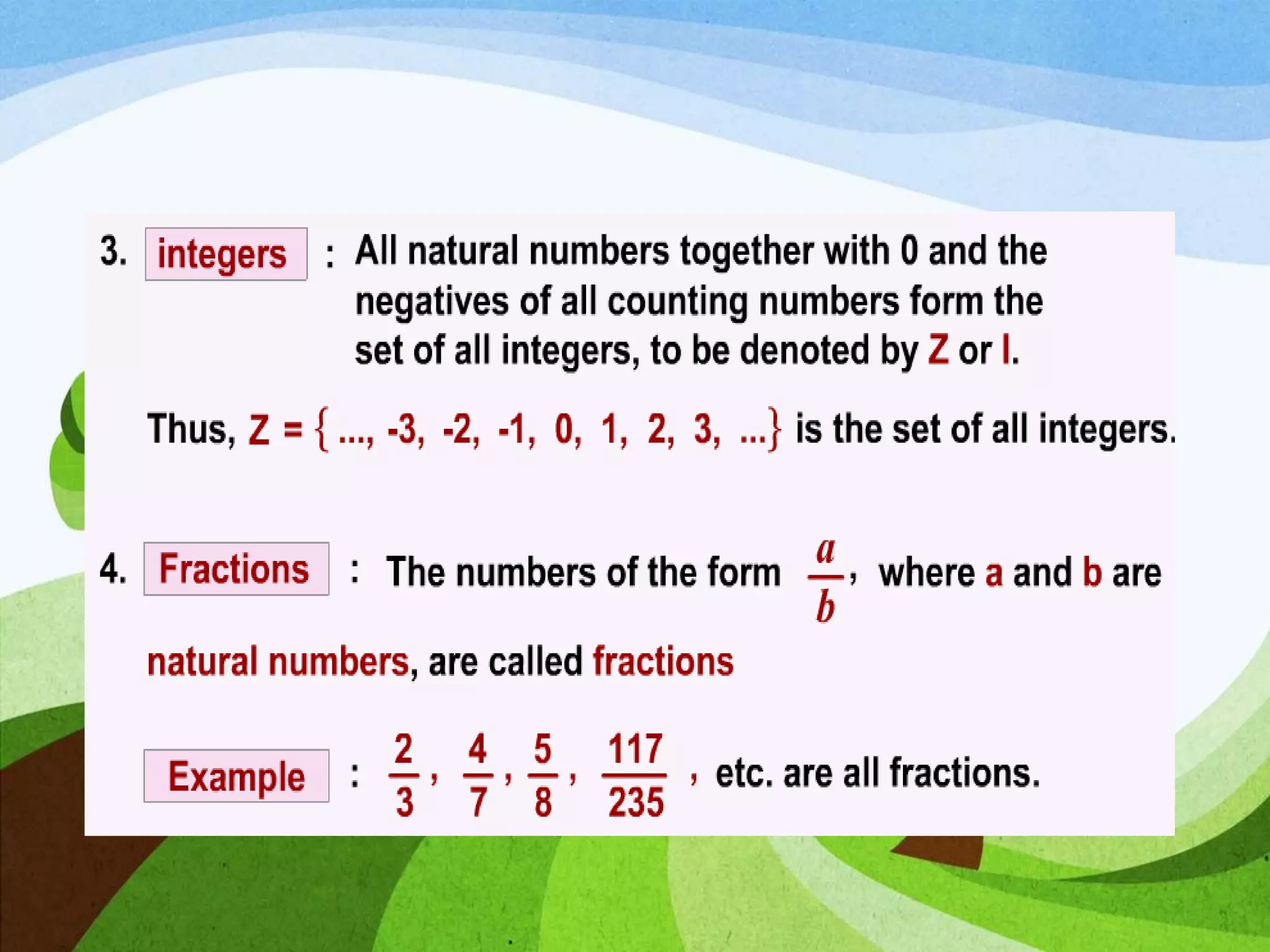

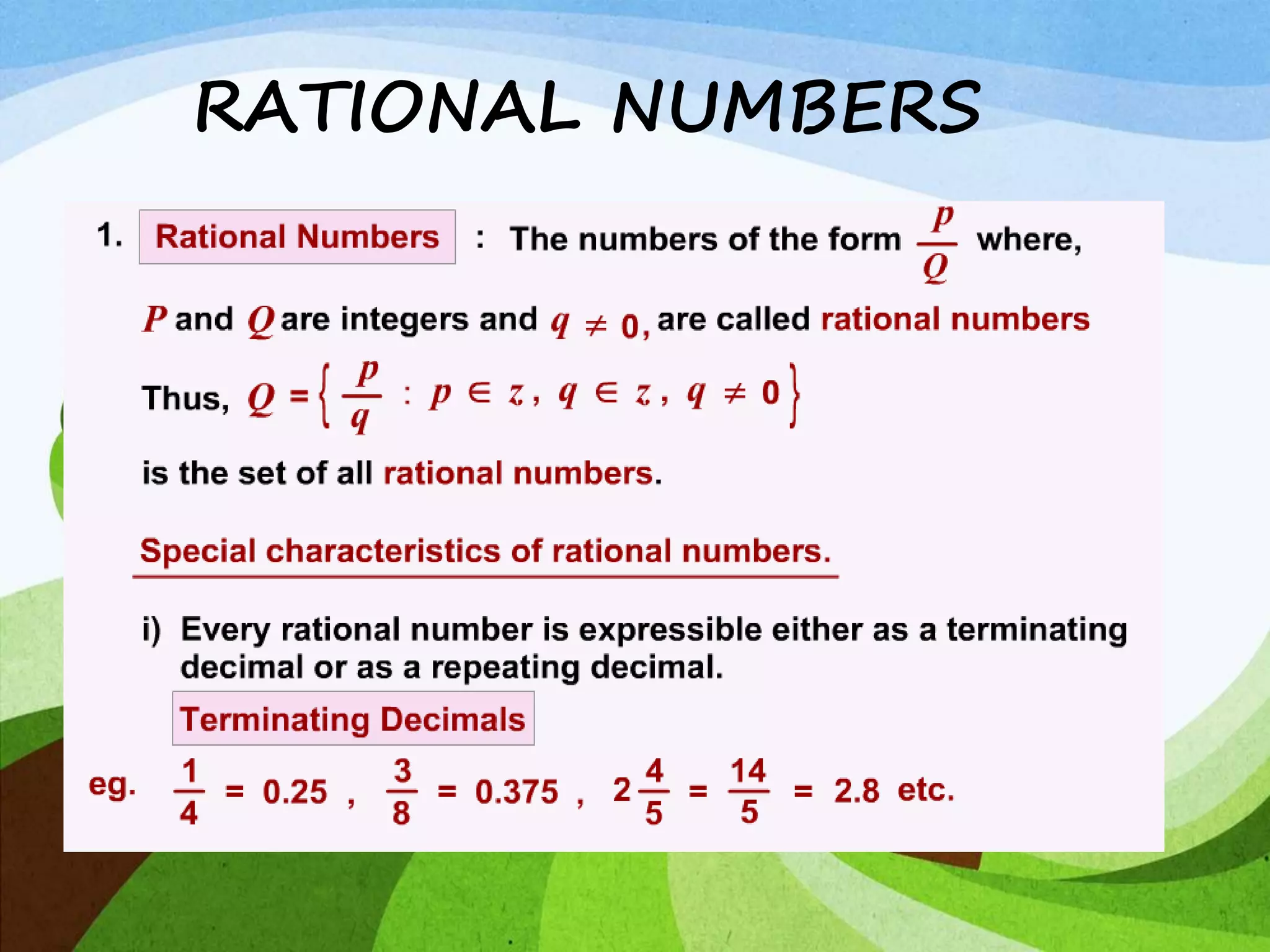

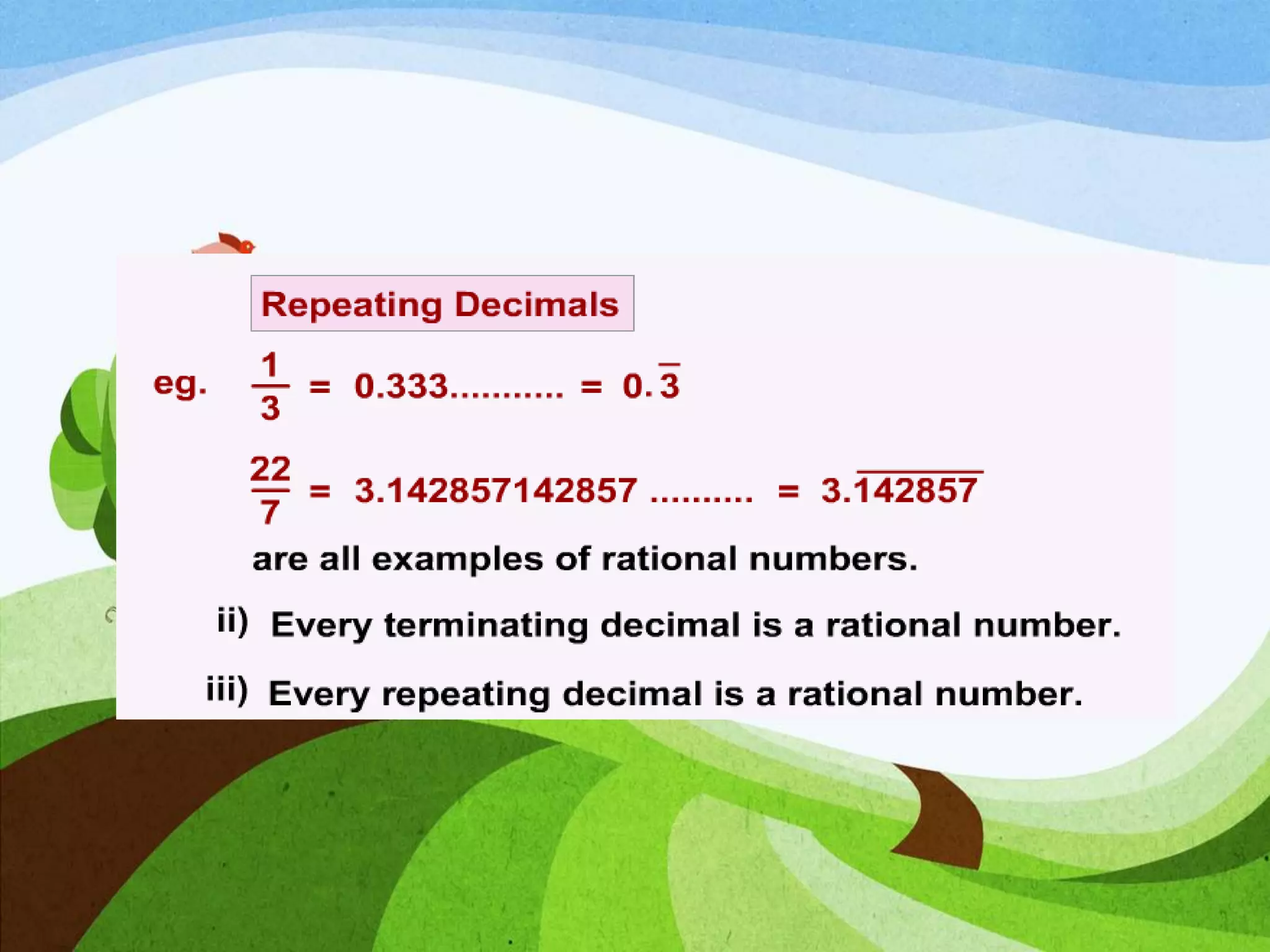

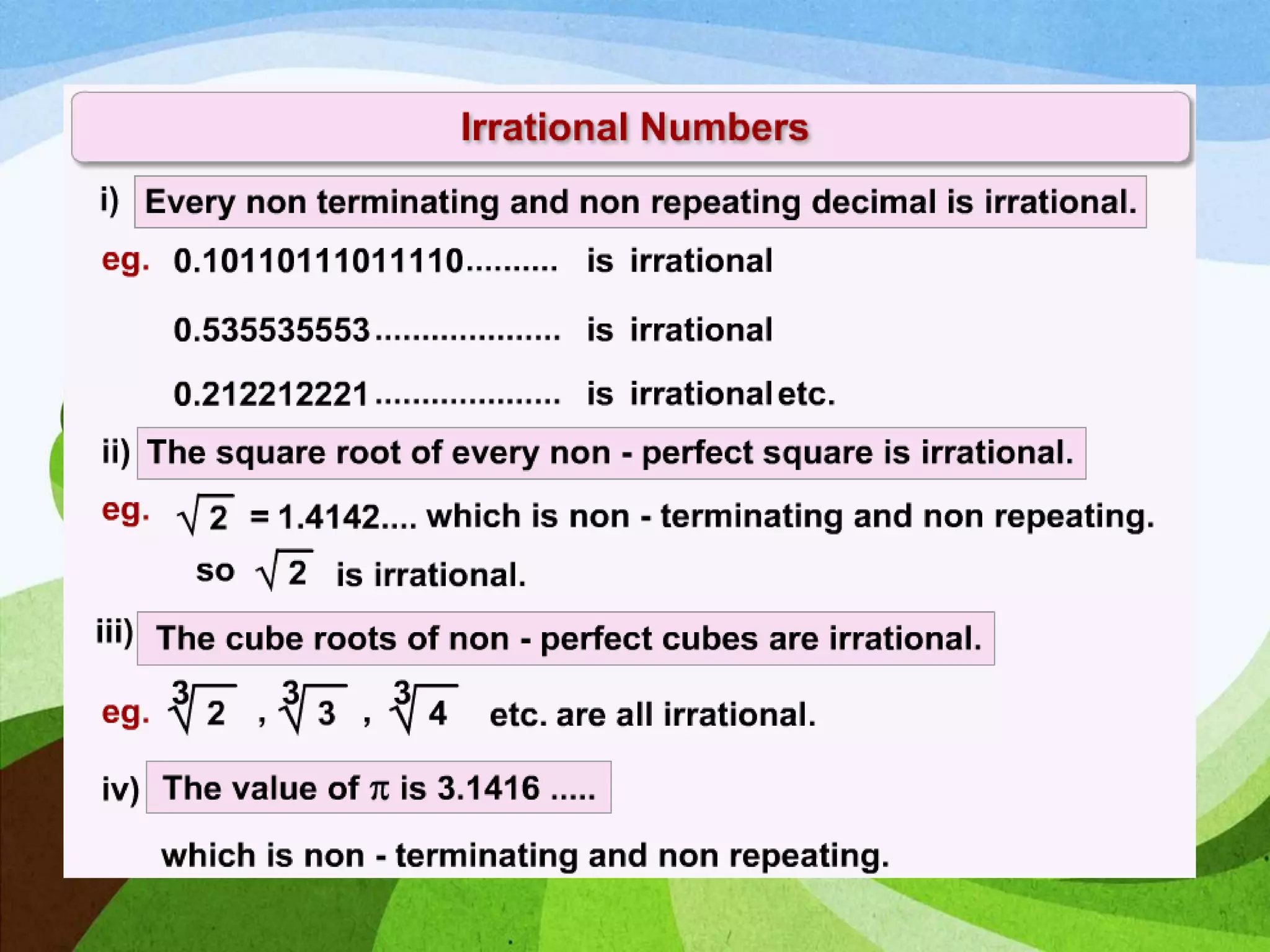

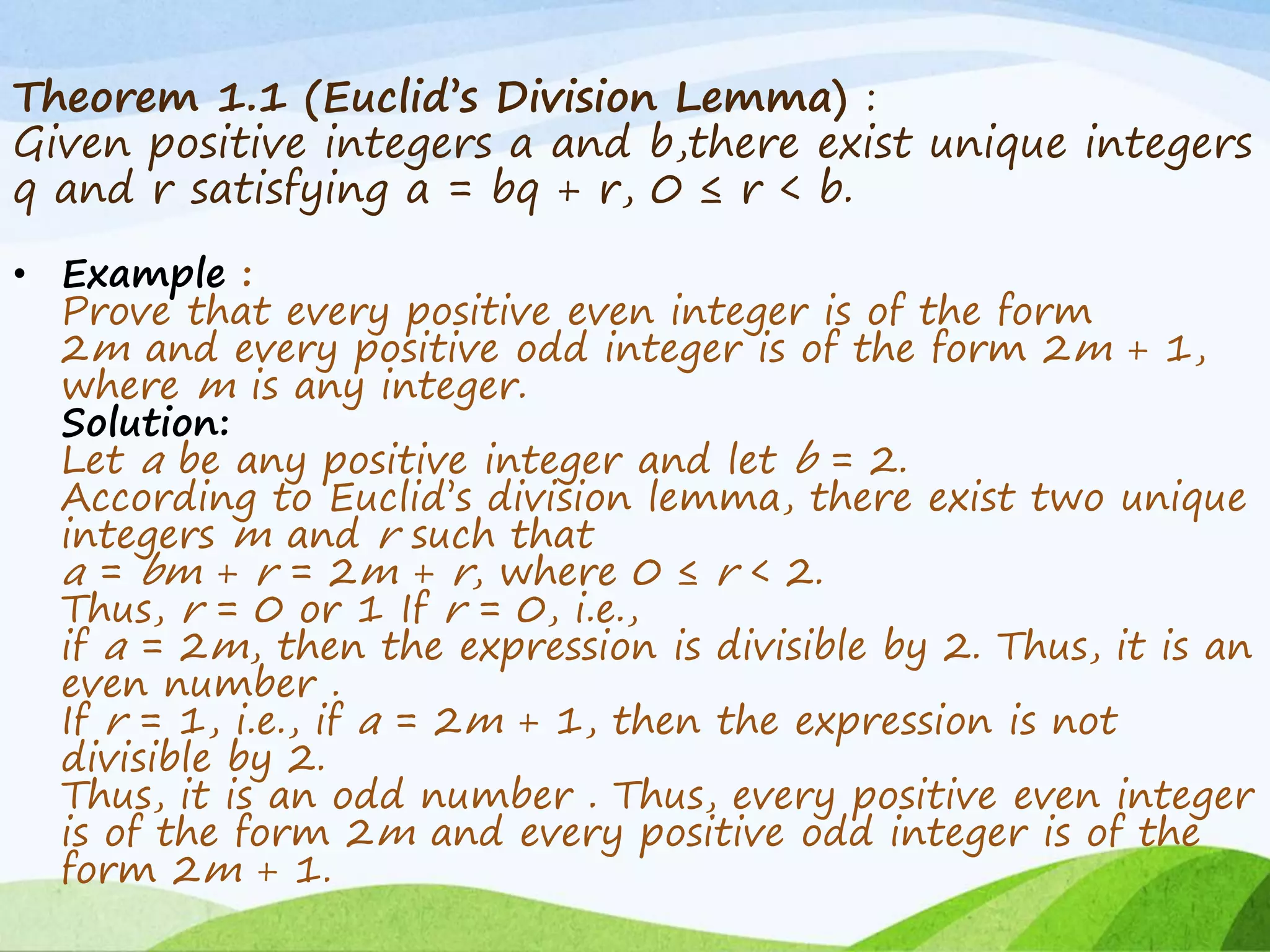

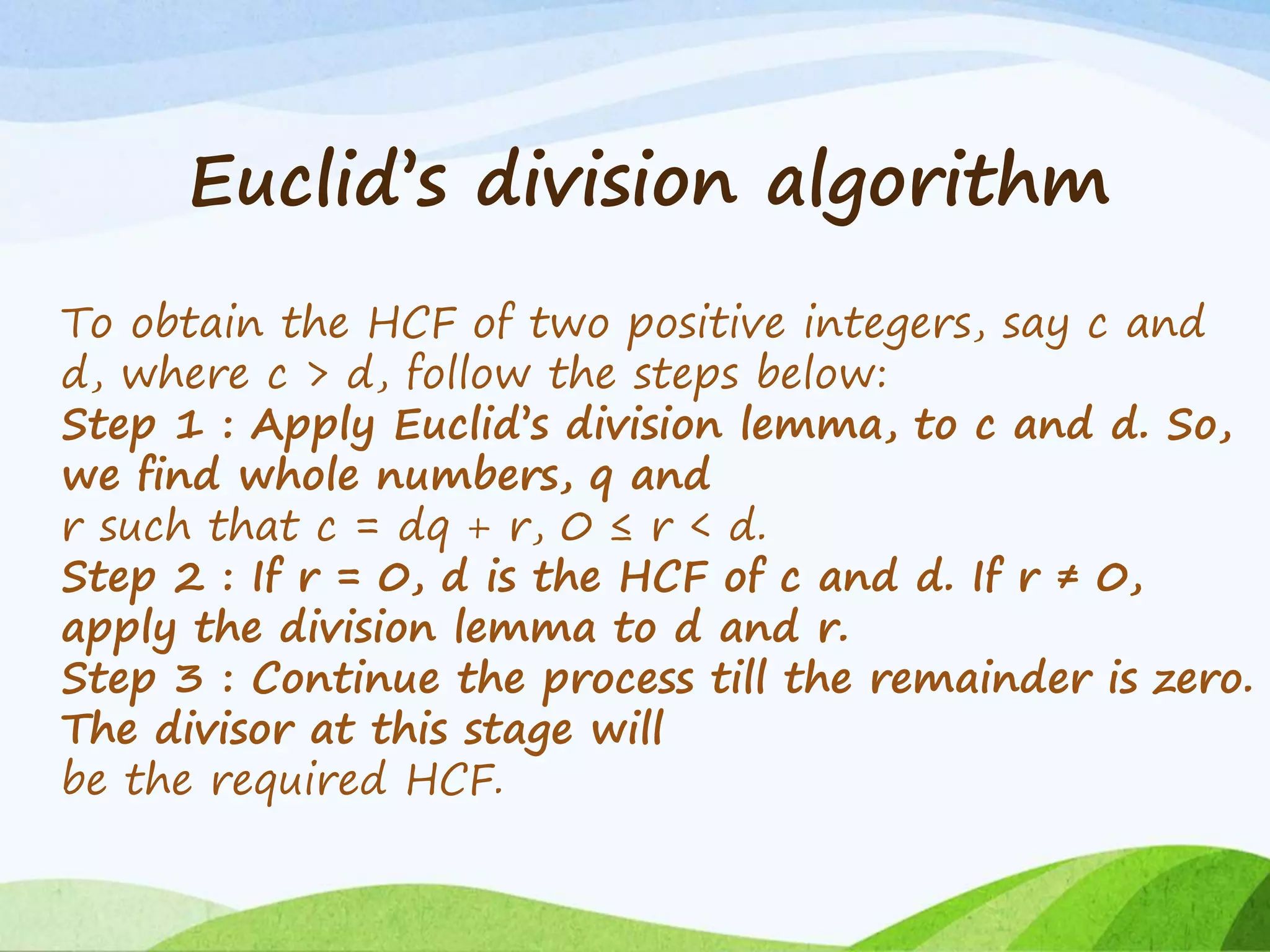

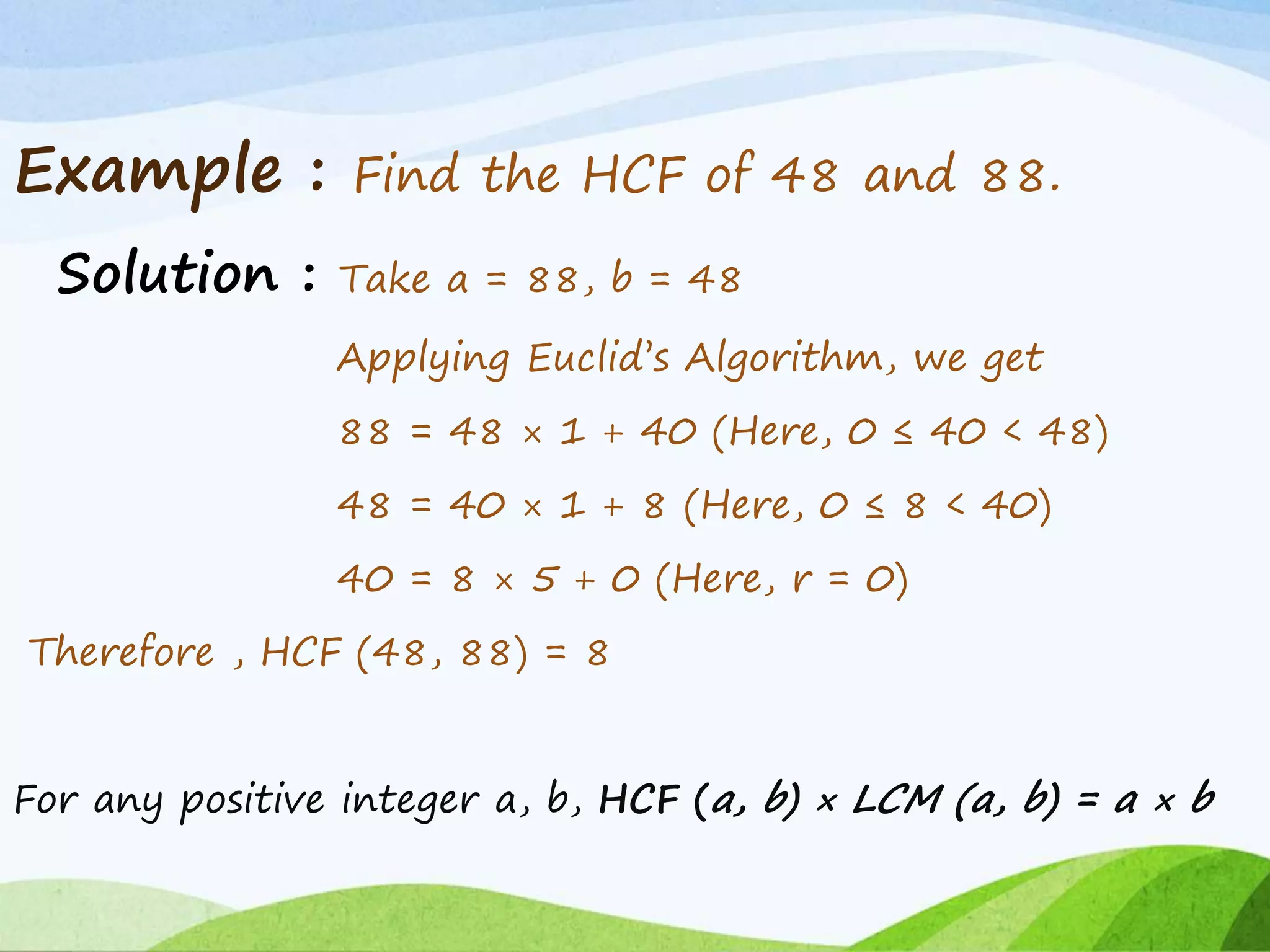

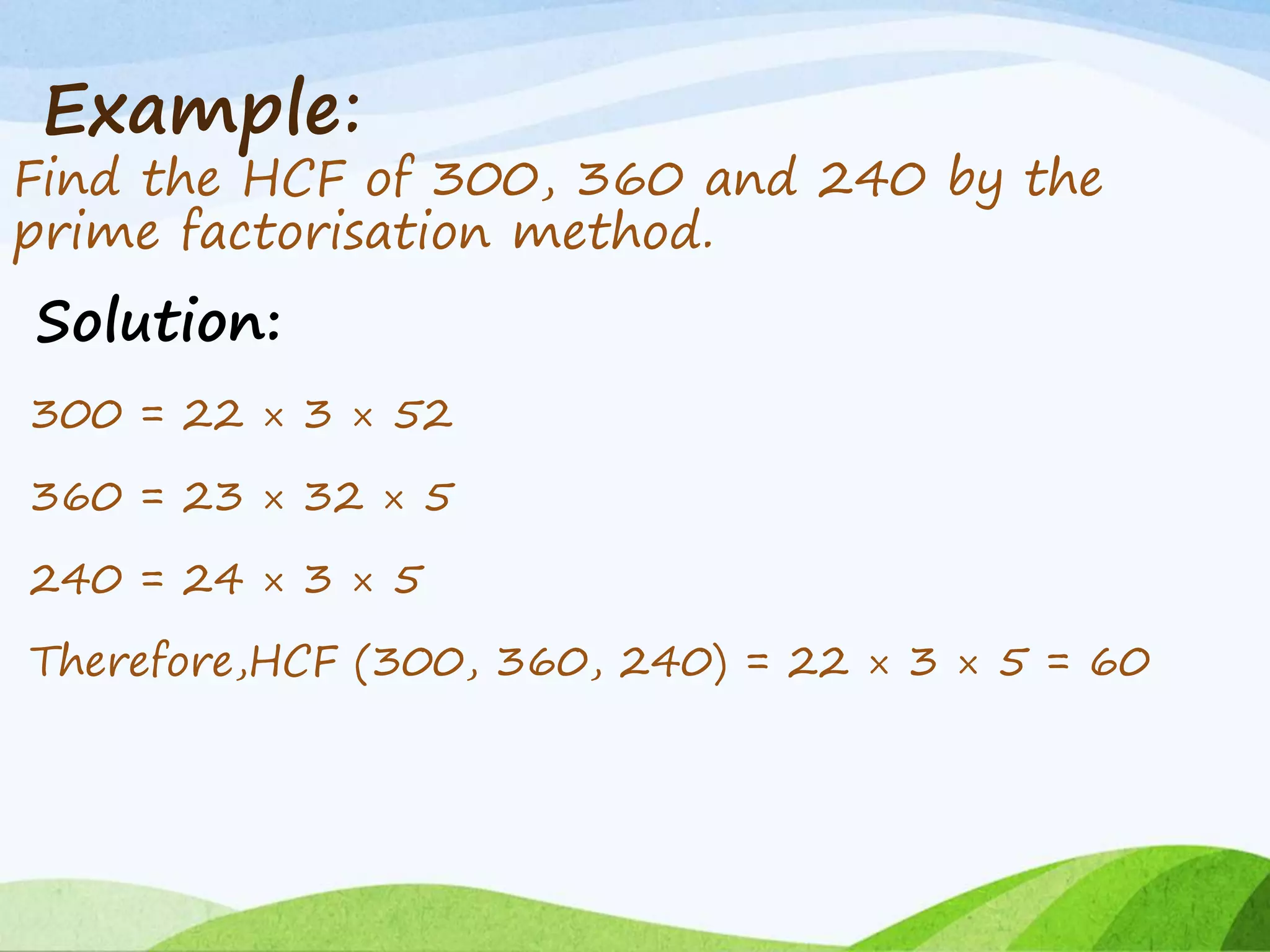

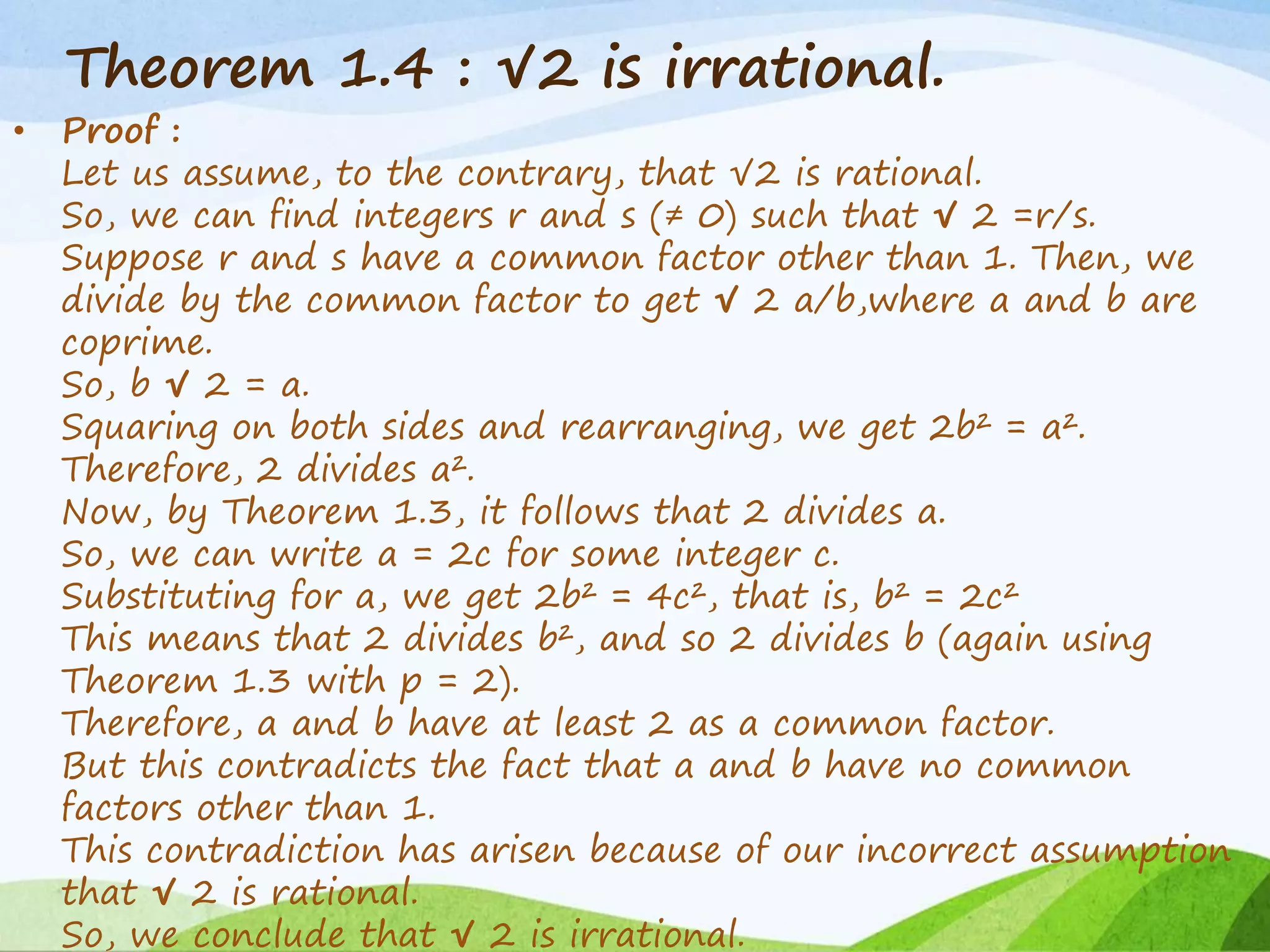

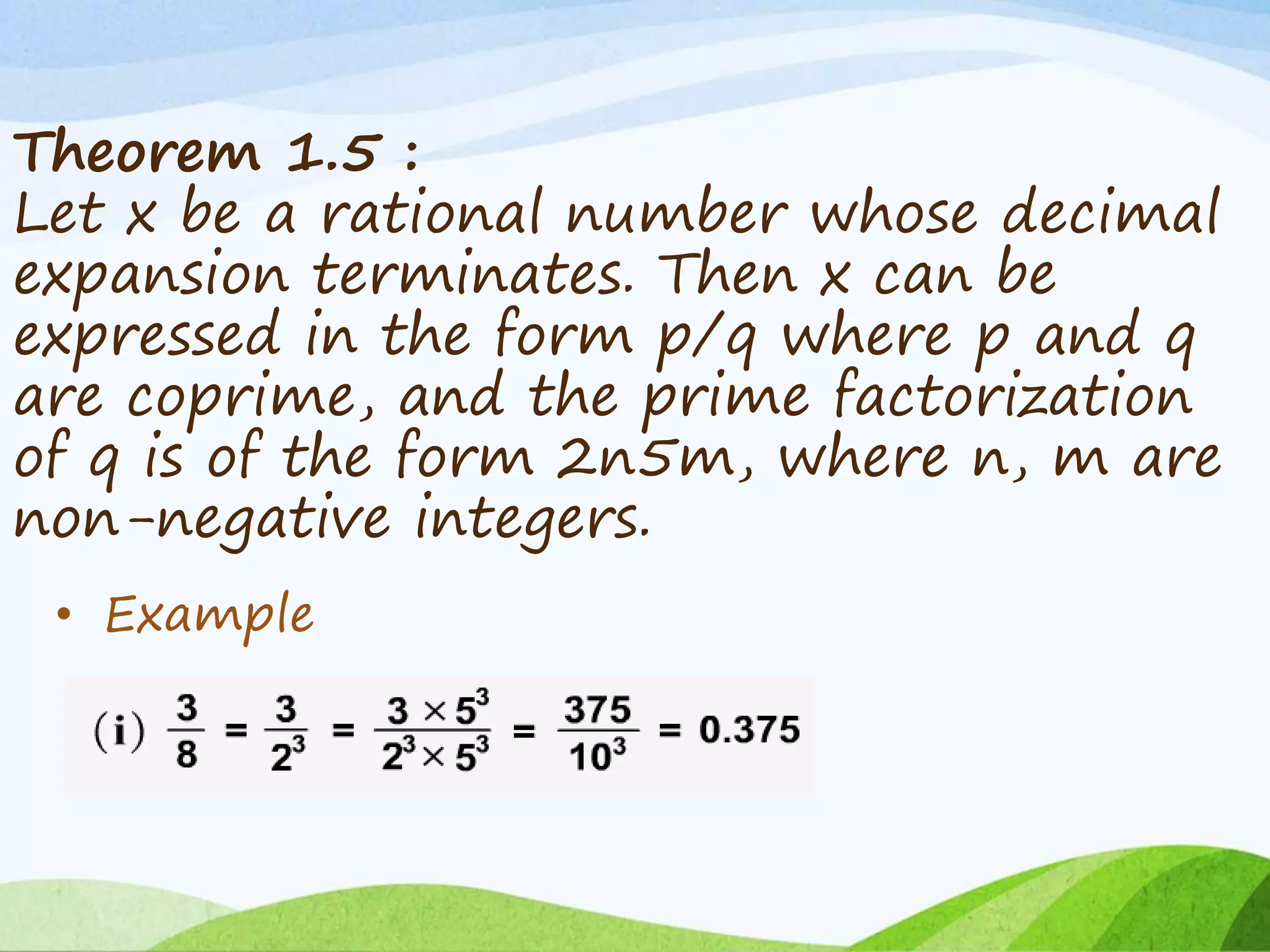

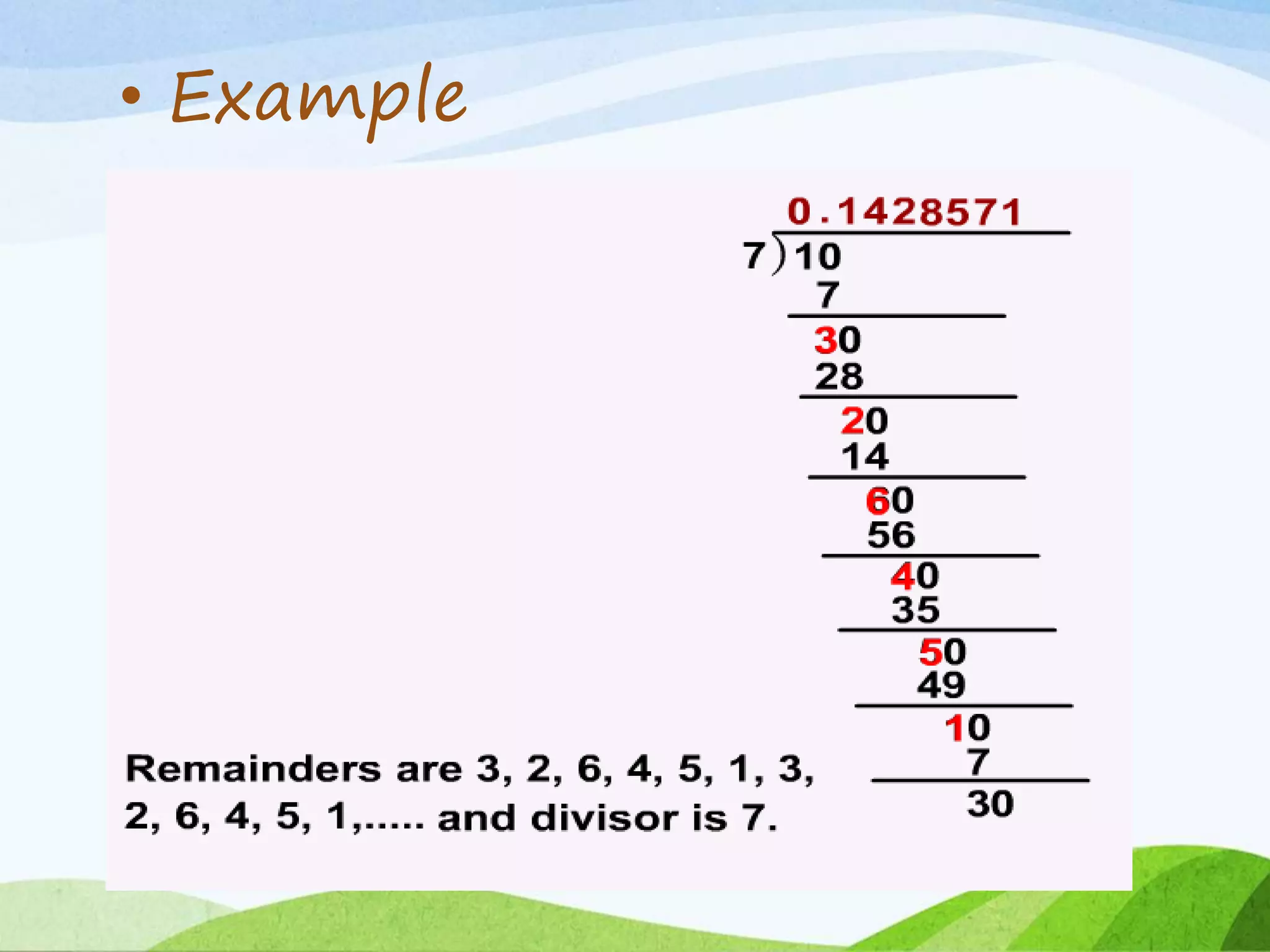

The document presents various theorems and concepts related to real numbers, including Euclid's division lemma, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, and properties of rational numbers. It explains the unique factorization of composite numbers and demonstrates how to find the highest common factor (HCF) using both division and prime factorization methods. Additionally, it discusses the irrationality of √2 and the conditions under which a rational number has a terminating or non-terminating decimal expansion.