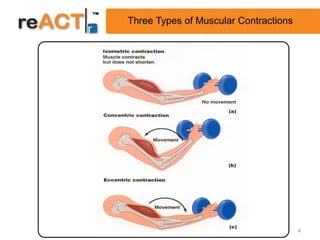

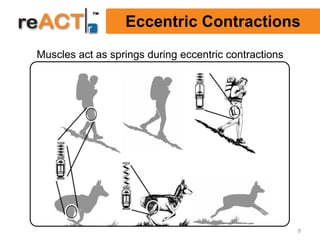

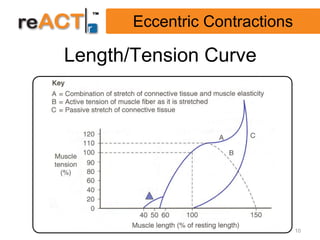

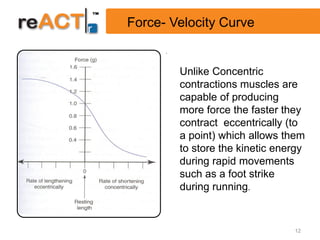

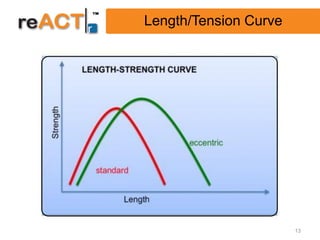

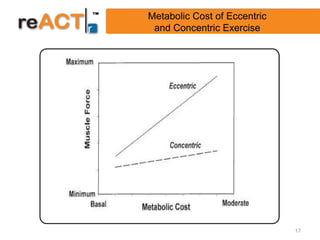

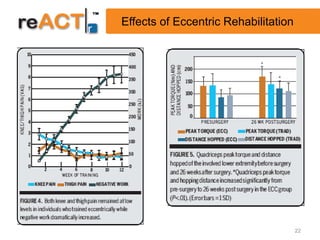

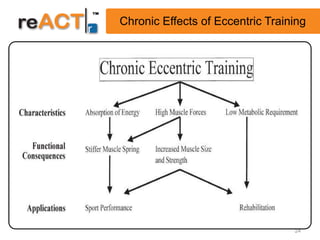

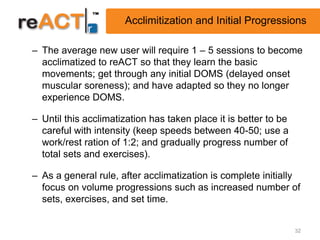

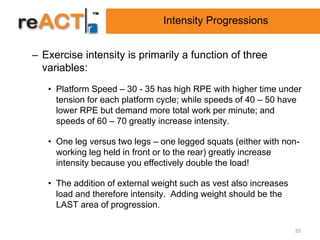

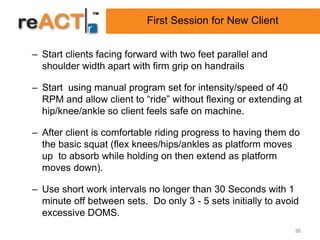

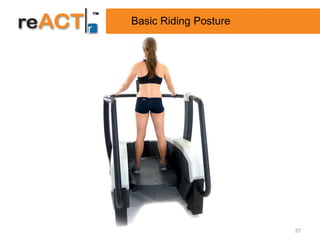

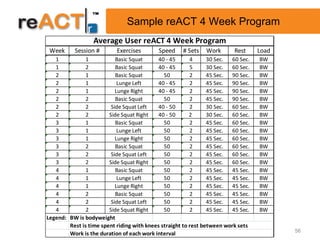

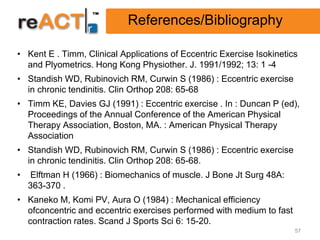

The document provides an in-depth overview of eccentric training, detailing the three types of muscular contractions: concentric, isometric, and eccentric, with a focus on the benefits of eccentric contractions in athletic training and rehabilitation. It discusses the Elftman principle of force production, the advantages of eccentric training for muscle hypertrophy and injury prevention, and outlines methodologies for effective eccentric training. Additionally, it highlights safety considerations, potential soreness, and the importance of progression in exercise intensity and complexity.