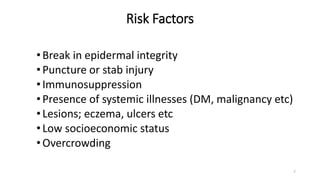

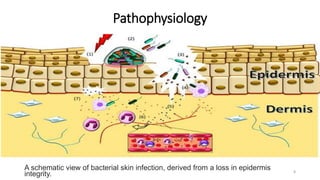

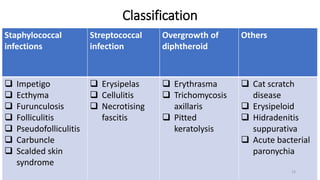

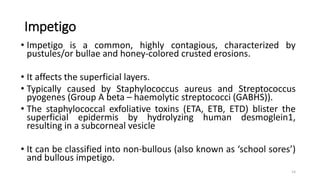

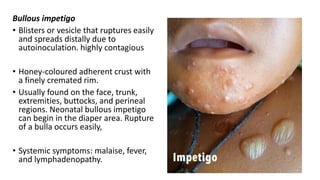

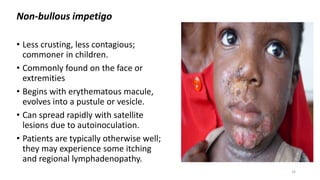

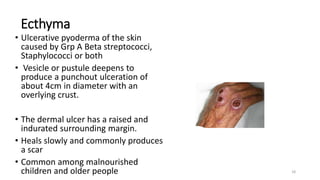

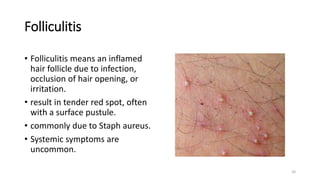

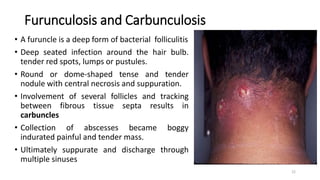

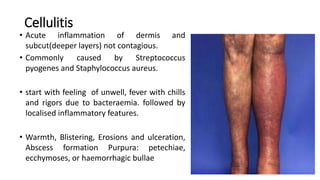

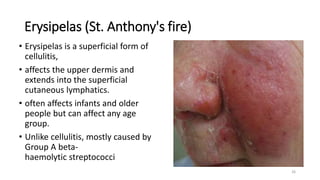

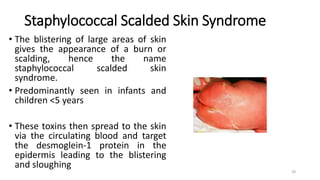

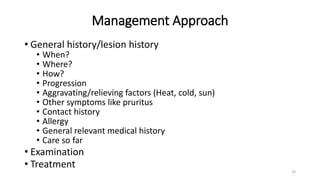

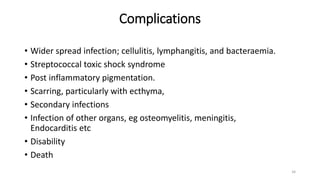

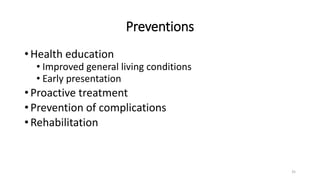

The document provides an overview of bacterial skin infections, detailing their epidemiology, risk factors, and management. It highlights the prevalence of infectious skin diseases, particularly in resource-poor regions, and categorizes various types of bacterial infections such as impetigo, cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis. Treatment recommendations and the importance of proactive management to prevent severe complications are also discussed.

![• Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, Malhotra R,

Jackson VA, Calciphylaxis: Risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment, Am J

Kidney Dis 2015;66(1):133-46.

• Auriemma M, Carbone A, Liberato DL, Cupaiolo A, Caponio C, De

Simone C, et al, Treatment of cutaneous calciphylaxis with sodium

thiosulfate: two case reports and a review of the literature. Am J Clin

Dermatol. 2011;12(5):339-46

• Olusola Ayanlowo et al. Pattern of skin diseases amongst children

attending a dermatology clinic in Lagos, Nigeria. Pan African Medical

Journal. 2018;29:162. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.29.162.14503]

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pyodermas-240125135458-60021ce8/85/Pyodermas-pptx-38-320.jpg)