The document outlines a pro-poor agricultural value chain development project in southern Mozambique, assessing the impacts of climate change on horticulture, cassava, and red meat value chains. It identifies rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns as significant challenges to these agricultural sectors while emphasizing the need for improved infrastructure, access to water, and climate-resilient practices. Recommendations include prioritizing infrastructure development, enhancing water access for irrigation, and promoting disease control in livestock to improve farmers' resilience to climate change.

![8

List of Figures

Figure 1: Annual mean total precipitation for each grid cell for the period 1981-2014. Data taken

from the CHIRPS dataset. Units [mm]....................................Erro! Marcador não definido.

Figure 2: Rainfall anomalies for each grid cell. Data taken from the CHIRPS dataset. Units [mm]Erro!

Marcador não definido.

Figure 3: Annual mean temperature for each grid cell for the period 1981-2014. Data taken from the

CRU TS3.23 dataset. Units [Celsius].......................................................................................24

Figure 4: Difference between decadal maximum mean temperature and maximum mean

temperatures for the entire period from 1981 to 2012 (a-c), decadal minimum mean

temperatures and minimum mean temperatures for the entire period from 1981 to 2012

(d-f). Data taken f m CRU TS3.23 dataset. Units [degree Celsius].........................................25

Figure 5: Climatological rainfall onset month (a) and cessation month (b), averaged for the period

1981 to 2014. Based on data from the CHIRPS dataset........................................................25

Figure 6: Decadal mean annual rainfall onset (a) and cessation (b) trends for the period 1981 to

2014. Based on data from the CHIRPS dataset. Units [days/decade]...................................26

Figure 7: Decadal trends in precipitation indices (table 1) over the period 1981 to 2014. Indices

shown at the top left and units in the top right. Based on data from the CHIRPS dataset.

Stippling indicates regions where trends are significant at the 95% level............................26

Figure 8 Projected multi-model mean changes (in %) in precipitation indices (table 1) for the period

from 2036 to 2065 under RCP8.5 emission scenario, relative to the reference period from

1976 to 2005. Stippling indicates grid points with changes that are not significant at the

95% level................................................................................................................................29

Figure 9 Individual NDVI values per district over a range of years, indicating the progressive drying of

the region, especially the western parts...............................................................................45

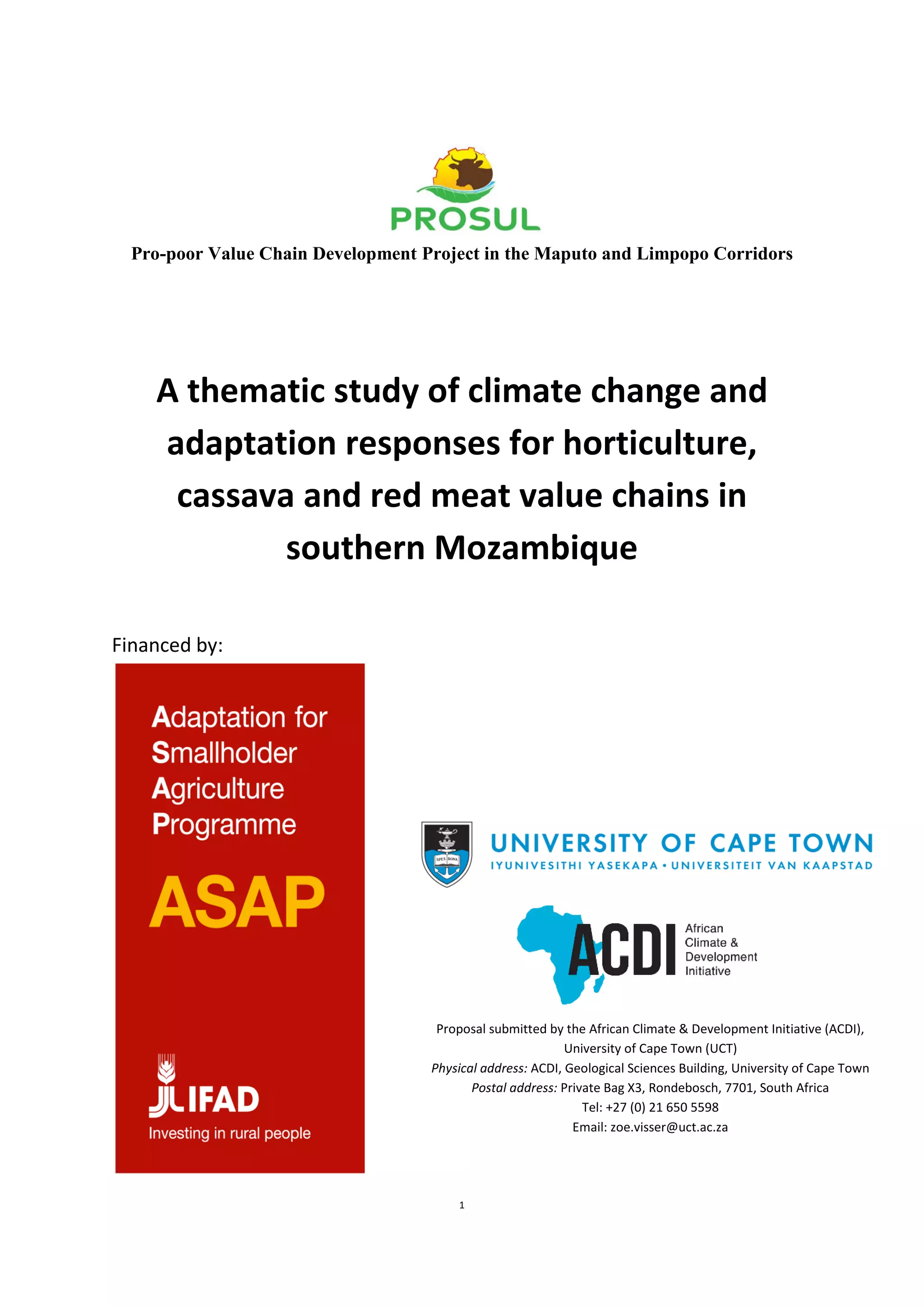

Figure 10: Within-season NDVI comparisons for the districts of southern Mozambique, indicating

how close each district was to the medium-term average for January. Redder colours

indicate the largest deficits. ..................................................................................................48

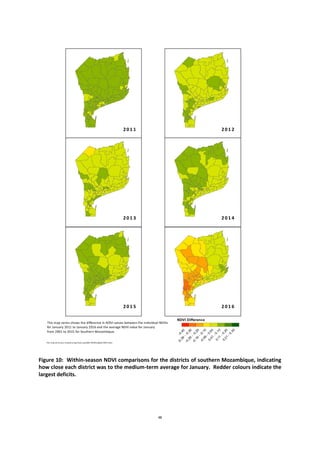

Figure 11: The NDVI anomaly for January 2016 at the height of the drought, relative to the long-

term mean for Januarys (2001-2015). The gold colours represent drought impacts on near

natural vegetation, influenced by national parks. The orange and red colours represent the

drought and human impacts on vegetation cover................................................................49

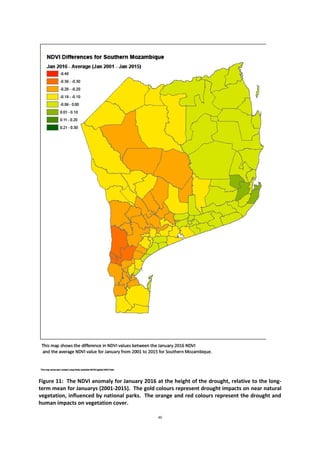

Figure 12: Flooding hazard map of southern Mozambique, based on satellite images of historically

flooded areas, in relation to districts. Source: FEWS NET (2014).........................................50

Figure 13 Priority areas (Postos) for value chain interventions - red meat and horticulture...............67

Figure 14 The First to fourth order model/schema of climate impacts (Source: (Petrie et al., 2014). 77

List of Tables

Table 1: PROSUL project provinces and districts for the value chains of red meat, horticulture and

cassava (Source: PROSUL, 2016). ..........................................................................................11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-8-320.jpg)

![20

Figure 1: Annual mean total precipitation for each grid cell for the period 1981-2014. Data taken

from the CHIRPS dataset. Units [mm]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-20-320.jpg)

![21

Figure 2: Rainfall anomalies for each grid cell for rainfall data from 1981-2014. Data were taken

from the CHIRPS dataset. Units [mm]

This chapter provides a trend analysis of historical climate data and downscaled rainfall projections

over southern Mozambique. Projections of temperature change from the various sources discussed

(Section 2.7) do not show the range of variations of rainfall during the downscaling process,

especially as altitudinal changes across the study region are small. Temperature changes are taken as

is from the GCM ensembles. The historical trend analysis reviews the period 1981-2014, while

projections focus on the 2036-2065 period under a high level emission scenario (RCP 8.5). For the

historical analysis, we have used two observed gridded data sets, CRU TS (monthly temperature

statistics) and CHIRPS (daily rainfall) respectively. The results of this analysis of historical

temperature data show a clear warming trend. Both maximum and minimum temperatures were

warmer, on average in the decade of 2000s. An analysis of extreme climate indices suggests that

rainfall is becoming more intense, yet with longer dry-spell durations in between. There are also

indications of a later onset of the rainfall season and an earlier cessation of rain, reflecting an overall

shortening of the rainfall season. We have used dynamically downscaled data from the Coordinated

Downscaling Experiment (CORDEX) for developing the future climate projections. Under a high-

emission scenario (RCP8.5 – which is what the world is currently tracking), projections indicate that

towards mid-century (2036-2065), the number of rainfall events may increase. This is coupled with

longer dry spell periods, indicating that rainfall may become more concentrated and intense into the

future.

2.6. Recent climate trends (1981-2014)

Studies of recent historical changes in climate in Africa, including Mozambique, are hampered by the

availability of meteorological station data. Gridded products based on satellite derived precipitation

estimates or merged satellite data and station observations are an alternative, provided their

accuracy is well known. Due to these constraints in observational weather station data, rainfall and

temperature data from Climate Research Unit (CRU TS 3.21, Harris et al., 2014) and Climate Hazards

Group InfraRed Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS, Peterson et al., 2013) are used to study the

historical changes. The CRU TS data is made up of monthly time series of various climate variables,

which include maximum and minimum temperature and rainfall. The data, which is based on over

4000 global weather stations, is available for the period 1901-2014 and is gridded to 0.5 x 0.5 degree

spatial resolution. The CHIRPS data, on the other hand, comprises daily rainfall data only. It is a

combination of satellite and weather station rainfall data and is available for the period 1981-2014,

gridded to 0.05 x 0.05 degree spatial resolution. Historical trends are calculated using linear

regression for each grid point for both CHIRPS and CRU datasets. The Mann-Kendall test was then

used to evaluate the statistical significance of trends at 95% confidence level. Statistical significance

implies that the result is unlikely to have occurred by chance. A lack of statistical significance does

not imply that changes have not occurred, but rather that they are most likely a result of

randomness rather than an underlying process.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-21-320.jpg)

![23

Figure 5 shows the climatological rainfall onset and cessation month for the region based on CHIRPS

dataset. Onset and cessation are defined from anomalous rainfall accumulation in a given day

[A(day)] as:

( ) ∑ ( )

Where R(n) is the daily rainfall and Rs is the long-term (1981-2014) daily mean (Liebmann et al.,

2007). The calculations used 1 July as the starting date, which is, climatologically, the driest month.

The date on which this sum [A(day), or anomalous accumulation] is a minimum is the date of onset,

while the date of the maximum sum marks the rainy season withdrawal. This method is both

objective and defined locally - that is, based on the climate of the area of interest.

Over Maputo province, rainfall starts in November while over Gaza and Inhambane it starts in the

following month of December. The cessation of rainfall over Gaza and Inhambane is in February

while over Maputo it is in February and March. For the period of 1981-2014, rainfall onset has

shown an increase in days, i.e., starting late by 5-15 days per decade over southern Maputo and

parts of Inhambane province (Figure 6) (note – the values of 5-15 days per decade is the response

only for the period of data viewed and does not imply a stable trend). In most of Gaza province

rainfall onset has shown a decrease of about 10-25 days per decade, which means that there is a

trend towards an earlier start of rainfall season. Over most of Maputo and parts of Gaza the rainfall

onset has shown a trend toward an earlier cessation of about 10-25 days, which means that the

rainfall season is getting shorter. In other regions of southern Mozambique, there is a trend towards](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-23-320.jpg)

![25

Figure 3: Annual mean temperature for each grid cell for the period 1981-2014. Data taken from

the CRU TS3.23 dataset. Units [Celsius].

Figure 4: Difference between decadal maximum mean temperature and maximum mean

temperatures for the entire period from 1981 to 2012 (a-c), decadal minimum mean temperatures

and minimum mean temperatures for the entire period from 1981 to 2012 (d-f). Data were taken

from CRU TS3.23 datasets. Units [degree Celsius].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-25-320.jpg)

![26

Figure 5: Climatological rainfall onset month (a) and cessation month (b), averaged for the period

1981 to 2014. Based on data from the CHIRPS dataset.

Figure 6: Decadal mean annual rainfall onset (a) and cessation (b) trends for the period 1981 to

2014. Based on data from the CHIRPS dataset. Units [days/decade].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-26-320.jpg)

![78

8. References

2SCALE, 2015a. 2SCALE | More Cassava from Mozambique [WWW Document]. URL

http://2scale.org/1010 (accessed 3.19.16).

2SCALE, 2015b. 2SCALE | DADTCO [WWW Document]. URL http://2scale.org/757 (accessed 3.19.16).

Arslan, A., McMcCarthy, N., Lipper, L., Asfaw, S., Cattaneo, A., 2013. Adoption and intensity of

adoption of conservation farming practices in Zambia, ESA Working paper No. 13-01.

Agricultural Development Economics Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations.

Bila, J., 2016. Coconut Lethal Yellowing Phytoplasma Disease in Mozambique: Diversity, Host Range,

and the Impact of Farming Practices on Disease Incidence (Doctoral Thesis). Faculty of Forest

Sciences Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology, Swedish University of

Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Uppsala.

Bournez, L., Cangi, N., Lancelot, R., Pleydell, D.R.., Stachurski, F., Bouyer, J., Martinez, D., Lefrançois,

T., Neves, L., Pradel, J., 2015. Parapatric distribution and sexual competition between two

tick species, Amblyomma variegatum and A. hebraeum (Acari, Ixodidae), in Mozambique.

Parasit. Vectors 8, 504. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-1116-7

Dias, P., 2012. Analysis of incentives and disincentives for cassava in Mozambique (Techniucal notes

series). MAFAP, FAO, Rome.

Dittrich, R., Wreford, A., Moran, D., 2016. A survey of decision-making approaches for climate

change adaptation: Are robust methods the way forward? Ecol. Econ. 122, 79–89.

doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.12.006

Dosio, A., Panitz, H.-J., 2016. Climate change projections for CORDEX-Africa with COSMO-CLM

regional climate model and differences with the driving global climate models. Clim. Dyn. 46,

1599–1625. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2664-4

Engelbrecht, C.J., Engelbrecht, F.A., Dyson, L.L., 2013. High-resolution model-projected changes in

mid-tropospheric closed-lows and extreme rainfall events over southern Africa. Int. J.

Climatol. 33, 173–187. doi:10.1002/joc.3420

Eucker, D., Reichel, B., 2012. Final Evaluation: Joint Programme on Environmental Mainstreaming

and Adaptation to Climate Change In Mozambique (Final Report No. UNJP/MOZ/085/SPA).

Millennium Development Goal Achievement Fund - Secretariat.

FAO, 2008. FAO: Agriculture: Cassava [WWW Document]. URL

http://www.fao.org/ag/agp/agpc/gcds/ (accessed 3.19.16).

FAO, 2004. Drought impact mitigation and prevention in the Limpopo River Basin: A situation

analysis. FAO Land and Water Division, Food and Agriculture Organiastion of the United

Nations, Rome.

Fauquet, C., Fargette, D., 1990. African Cassava Mosaic Virus: Etiology, Epidemiology, and Control.

Plant Dis. 74, 404–411.

Favretto, N., Stringer, L.C., Dougill, A.J., Dallimer, M., Perkins, J.S., Reed, M.S., Atlhopheng, J.R.,

Mulale, K., 2016. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis to identify dryland ecosystem service trade-

offs under different rangeland land uses. Ecosyst. Serv. 17, 142–151.

doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.12.005

FEWS NET, 2014. USGS FEWS NET Data Portal: Africa. FEWS NET.

Fontana, V., Radtke, A., Bossi Fedrigotti, V., Tappeiner, U., Tasser, E., Zerbe, S., Buchholz, T., 2013.

Comparing land-use alternatives: Using the ecosystem services concept to define a multi-

criteria decision analysis. Ecol. Econ. 93, 128–136. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.05.007

Füssel, H.-M., Klein, R.J.T., 2006. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments: An Evolution of

Conceptual Thinking. Clim. Change 75, 301–329. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-0329-3

Meneses-Tovar, C., 2011. NDVI as an indicator of degradation. Unasylva 238 Vol 62 20112 62 (2).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-78-320.jpg)

![79

Niang, I., Ruppel, O.C., Abdrabo, M.A., Essel, A., Lennard, C., Padgham, J., Urquhart, P., 2014. Africa,

in: Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee,

M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., Girma, B., Kissel, E.S., Levy, A.N., MacCracken, S.,

Mastrandrea, P.R., White, L.L. (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and

Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth

Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1199–1265.

Omuto, C.T., Vargas, R.R., Alim, M.S., Paron, P., 2010. Mixed-effects modelling of time series NDVI-

rainfall relationship for detecting human-induced loss of vegetation cover in drylands. J. Arid

Environ. 74, 1552–1563. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.04.001

Petrie, B., Chapman, R., Midgley, A., Parker, R., 2014. Risk, vulnerability and Resilience in the

Limpopo River Basin: Climate change, water and biodiversity - a synthesis.

PROSUL, 2016. Annual Progress Reports 2015 (January-December 2015). PROSUL, Centre for the

Promotion of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Republic of

Mozambique.

Sruthi, S., Aslam, M.A.M., 2015. Agricultural Drought Analysis Using the NDVI and Land Surface

Temperature Data; a Case Study of Raichur District. Aquat. Procedia, INTERNATIONAL

CONFERENCE ON WATER RESOURCES, COASTAL AND OCEAN ENGINEERING (ICWRCOE’15) 4,

1258–1264. doi:10.1016/j.aqpro.2015.02.164

Tezara, W., Mitchell, V.J., Driscoll, S.D., Lawlor, D.W., 1999. Water stress inhibits plant

photosynthesis by decreasing coupling factor and ATP. Nature 401, 914–917.

doi:10.1038/44842

Tivana, L., Da Cruz Francisco, J., Bergenståhl, B., Dejmek, P., 2009. Cyanogenic Potential of Roasted

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) roots Rale from Inhambane Province, Mozambique.

Czech J. Food Sci. 27, S375–S378.

Tvedten, I., 2011. Mozambique Country Case Study: Gender Equality and Development (World

Development Repor 2012: Gender Equality and Development: Background Paper). World

Bank Group, Washington, DC.

UNCTAD, 2016. Merchandise trade matrix, exports and imports to world by product groups, annual,

1995-2014 - Mozambique Data Portal [WWW Document]. Knoema. URL

http://mozambique.opendataforafrica.org//UNCTADMTMEIWCG2016/merchandise-trade-

matrix-exports-and-imports-to-world-by-product-groups-annual-1995-2014 (accessed

12.6.16).

Way, D.A., Katul, G.G., Manzoni, S., Vico, G., 2014. Increasing water use efficiency along the C3 to C4

evolutionary pathway: a stomatal optimization perspective. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3683–3693.

doi:10.1093/jxb/eru205

Whipp, L., Daneshkhu, S., 2016. Big business identifies appetite for plant-based milk [WWW

Document]. Financ. Times. URL https://www.ft.com/content/7df72c04-491a-11e6-8d68-

72e9211e86ab (accessed 11.22.16).

Williams, C.A., Hanan, N.P., 2011. ENSO and IOD teleconnections for African ecosystems: evidence of

destructive interference between climate oscillations. Biogeosciences 8, 27–40.

doi:10.5194/bg-8-27-2011

Yengoh, G., Dent, D., Olsson, L., Tengberg, A., Tucker, C., 2014. The use of the Normalized Difference

Vegetation Index (NDVI) to assess land degradation at multiple scales: a review of the

current status, future trends, and practical considerations. Lund University Center for

Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS), and The Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel of the

Global Environment Facility (STAP/GEF).

2SCALE, 2015a. 2SCALE | More Cassava from Mozambique [WWW Document]. URL

http://2scale.org/1010 (accessed 3.19.16).

2SCALE, 2015b. 2SCALE | DADTCO [WWW Document]. URL http://2scale.org/757 (accessed 3.19.16).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/prosulclimatechangeadaptationthematicstudy-170321135754/85/Prosul-climate-change-adaptation-thematic-study-79-320.jpg)